Our First “Loop” Adventure

THE PERCEPTIONS OF “BLOW-INS”

DESPITE ALL THE “CELTIC TIGER” TALES of progress and prosperity and Ireland’s pulsating aura of newfound confidence (some even claim it’s becoming cloyingly complacent at times—others claim “the bubble has to burst soon!”)—in places like Beara you still sense a timeless quality in those great elemental aspects of shattered mountain ranges, sea-gouged cliffs, black water lakes, vast moors, and miasmas of peat bogs. These have always been the true touchstones of this strong and ancient land—this haven of great poets, artists, and writers, whose works resonate with primal energies and the ancient pagan rhythms of long-forgotten languages and legends and the horrors of their decimated, diaspora-plagued heritage.

No matter how capsulized you make these Irish histories, how euphemistically you paraphrase the sequences of ethnic “displacements,” cultural annihilations, endless centuries of occupations and Troubles, heart-shattering poverty, the terrible famines, the mass emigrations, the constant battles against the state and the Catholic church for freedom and liberation—the emergence of the “peaceful and prosperous” nation of today is a nonfictional gothic melodrama far more complex and convoluted than any novel could ever be.

The recent transformations here have been miraculous and yet tinged with ironies. In a land now flush with new affluence and with more Mercedeses per capita than any other country on earth, including Germany, you can still see the Angelus bells being rung on TV twice a day and people pausing to pray in the street to the Blessed Virgin. And out in the wilder parts of Connemara, Donegal—and Beara—visitors still seek out scenes and experiences of the “old ways”—the ashling—of simple sustenance lives lived close to the earth and the ocean and within their own remote, close-knit communities.

It’s always fascinating to see how our tastes in and reactions to landscape and travel in general have changed over the centuries. Today’s first-time “touchstone-seeking” explorers of Beara are invariably enchanted by its bold, burly mountains, its wild heather and gorse-strewn moors, and that magical sense of discovering secret Brigadoon valleys glowing with that iridescent sheen of green that is pure Emerald Isle.

But it was not always so. Even a superficial search of reactions from celebrities and historical figures over the last couple of centuries reveals far less rosy-hued accounts and opinions. While today, for example, most of us are bemused by the little, narrow, winding, and vegetation-crammed boreen lanes here, Prince Hermann von Pückler-Muskau portrayed his journeys around Beara in 1828 as “indescribably difficult.” And William Wordsworth, whose purpled poems often exceeded the normal bounds of adjectival and emotional restraint, limited his comments on Beara roads to a single word: “Vile!” Sir Walter Scott, however, was far more enthusiastic, describing the scenery of Beara and County Kerry as “the grandest sight I have ever seen.”

And then, of course, there’s the weather. The plans of poor old Theobald Wolfe Tone, who attempted to harness a French armada here to drive the English from Ireland in 1796, were decimated by Beara’s notoriously fickle climate. “Dreadfully wild and stormy and easterly winds which have been blowing furiously and without intermission since we made Bantry Bay, have ruined us,” he wrote before being captured and executed in 1798.

Similar outrage also pours from countless early “travel memoirs,” although one of the less voracious commentaries by the novelist Marie-Anne de Bouvet (1889), attempts a more balanced summation: “The climate of Ireland is vexatious rather than absolutely bad, and it has consolations the more delightful because they come unexpectedly.” A splendid example of damning with faint praise.

And then came such social commentary as this 1818 description by Georgiana Chatterton of the local Beara people in her best-selling travel book, Rambles in the South of Ireland: “They were the wildest-looking people I ever beheld…and the appearance of the dwellings of the peasantry was more truly wretched than I have ever seen…Some of the younger children were completely naked.”

Rose Trollope, however, wife of the famous novelist Anthony, obviously had a tolerance for Beara, as they both enjoyed several family holidays in Glengarriff. Anthony quickly absorbed the nuances and subtleties of Irish life in his official position with the post office in Banagher, which he portrays vividly in his novel The Kellys and the O’Kellys. However, in 1849, Anthony’s mother, Fanny (herself a distinguished author), did not share their enthusiasm and found: “the food detestable, the bedrooms pokey, turf fires disagreeable, and so on, and so on.”

Virginia Woolf, like so many other celebrities of the time, also enjoyed a vacation in Glengarriff in 1934, and although she and her husband, Leonard, toyed with the idea of buying property here, she also saw the “underbelly” of life in the country, which she described in her typically terse and acerbic manner: “How ram-shackle and half-squalid the Irish life is, how empty & poverty-stricken.” (Interesting how she makes “half-squalid” sound far worse than just simply ‘squalid.’)

As the twentieth century progressed and conditions improved along the peninsula in terms of roads, housing, and employment, especially in fishing and the British naval yards at Castletownbere, the mood and reactions of visitors began to improve. One particular commentary by Sean O’Faolain in his book An Irish Journey (1941) combines the direness of the past with a new romantic effervescence celebrating the power and majesty of this remarkable corner of the country: “If there is in Ireland a harder world than the Bere Peninsula, a tougher life, a sterner fight against all that this loveliness of nature means in terms of poverty and struggle and near-destitution I have yet to find it.” But then he switches tone and lets his eloquence flow:

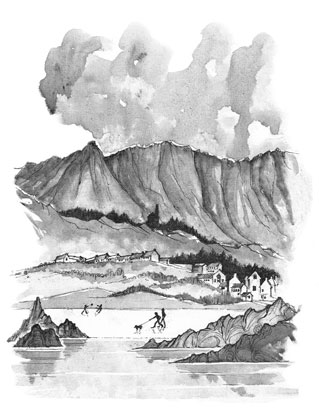

Few more lovely seascapes exist in Ireland than that which unfolds itself on the walk to Glengarriff and beyond…The sweeping grandeur…the vast elemental infinities…the Glen, as we call it in County Cork, has three things peculiar to itself. It has tiny refuges of inlet nooks and coves where the mind can dream itself into a drowsy peace for days on end, hidden low-tide or high-tide lagoons, lovely at any season, little islands where one can bathe and bask, silent but for the cry of a curlew or gull, or the chattering of herons or the suck-suck of the seaweed caressing the rocks. It has foliage of a tropical variety in abundance. It has a climate so mild that the place flowers with rare flora, and on the more moist summer days, the bay lies heavy as molten metal, and the very rocks seem to melt, and everything swoons in a land-locked sleep.

Ironically, while the Beara has remained relatively aloof and unexplored, it is seen today by many to capture the very essence of the Irish people and the enormous power and beauty of the land itself. “Beara,” I was told by one proud resident, “is just quite simply the best place in the whole of Ireland.” And by the time Anne and I left at the end of our seasons here, we were of course in total agreement with such sentiments.

SCURRYING FROM KILLARNEY AND THE RING OF KERRY

AND WE ARE BOTH in total agreement about Killarney and the Ring of Kerry too that runs around the Iveragh Peninsula. Out of season, if the weather holds, this is indeed an enchanted realm of soaring mountain ranges with such entrancing names as Macgillycuddy’s Reeks reflected in broad forest-edge lakes and a tumultuous chiseled coastline pounded by the Atlantic Ocean. A dramatic dreamworld indeed that conjures up all the boisterous charms of the Ireland of popular inspiration.

But come during the peak late spring to early autumn season and you’ll need to brace yourself for a traumatic transformation when the charmingly upmarket and architecturally flamboyant Victorian town of Killarney itself, with its plethora of palace-like hotels and resorts, suddenly becomes Ireland’s most popular tourist nexus after Dublin. The relatively narrow roads that encircle the Ring of Kerry attract dawn-to-dusk processions of bumper-to-bumper coach traffic, all visiting the same “top spots” (the National Park, Muckross House and Abbey, the Ladies’ View panorama, Ross Castle et al.).

For those whose images of Ireland conjure up shamrock-garnished horse and carriage rides, leprechaun-filled souvenir shops, pseudo-céilí concerts in “traditional pubs,” KISS ME QUICK I’M IRISH souvenirs in every imaginable guise, and an exuberance of blarney that even make Japanese tourists wary of overkill hype—then this will be seen as some kind of paddywackery paradise.

For those, however, who are willing to work a little harder to discover a more authentic Ireland—may we gently continue to entice you to travel a score or so miles from the crush of Killarney and venture south to the next peninsula, which offers a far more authentic experience altogether.

Here on Beara the scenery is as rugged as a rhino’s carapace and formed largely of sandstone, with slate and igneous intrusions, all bent, buckled, and fissured by the Armorican tumult of over three hundred million years ago. The land is creased, incised, and gashed by constant conflicts with the oh-so-Irish elements of rain, frost, and that miasma of “mizzle” (mist and drizzle) that cocoons the high ancient places.

But we don’t mind at all. We’re out of the Killarney chaos and into the wild country now, switchbacking up the steep narrow road to Moll’s Gap and a quick pause for a gourmet snack (one of the thickest, creamiest, and richest quiches ever) at the famous Avoca Café perched on the scoured treeless peak here.

And then it’s all downhill, looping and laughing together as we see signs for Kenmare and the Ring of Beara. Anne reads a short outspoken commentary from one of our guidebooks:

The Beara peninsula is as beautiful as the Dingle, far to the north, but it is perhaps the least known of the western peninsulas. It is more rugged and till now lonelier than the others. Its fate is being argued. One faction, led and supported by conservationists, tourists, and many German, Dutch and English “blow-in” settlers, is for keeping things much as they are. The other, including a number of influential locals, want the god Development: roads, houses, hotels and industry to match Ireland’s economic surge of the 1980s and 1990s. Having fouled up your own countries, these Irish seem to be saying, you want to stop us fouling up ours, and that is for us to decide.

“I assume this ‘fouling’ business doesn’t refer to our peninsula,” I said.

“Oh—so it’s ‘our peninsula’ now, is it? Getting a little possessive aren’t we, especially as you haven’t even see the place yet!” Anne said, laughing.

“Well—it says ‘least known,’ so I guess we’ve picked the right one…and I’ve heard nothing about any ‘fouling.’”

And Kenmare certainly appears foul free. In fact, after all the hype and hullabaloo of Killarney this is a model town of decorum and grace. Hidden back behind the cozy little cluster of downtown stores are two of Europe’s most prestigious hotel-resorts. First is “High Victorian” Park Kenmare tucked away at the top end of main street, laden with antiques and tingling with olde world country house charm. Then comes Sheen Falls Lodge, definitely one of those “if you have to ask the price here you can’t afford it” places set on a three-hundred-acre estate with tree-shaded walks down to the long, ocean-lapped bay known somewhat misleadingly as the Kenmare River.

From even a superficial glance at this coy little town you sense a distinctly non-Irish heritage here. And so it was. In fact the notorious diarist Macaulay, ever prone to vast exaggerations in his writings, described predevelopment conditions here in the seventeenth century when Sir William Petty arrived to “make profitable sense of the country. For having been awarded a large grant of land for services to the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, he had to face half-naked savages, who could not speak a word of English and who made themselves burrows in the mud and lived on roots and sour milk…scarcely any place…was more completely out of the pale of civilizations as Nedeen” [Kenmare’s original name].

So—as happened all across Ireland when the “let’s get things organized here” Britishers moved in—Sir William set about creating ironworks, lead mines, fisheries, and other industries and, in 1670, founded a very English-like village in a tree-laced hollow. He even tried to entice scores of “doughty maidens” from England to come and “civilize our local natives” and set up a flourishing Protestant society. Things didn’t quite work out in so utopian a manner, but the place began to truly flourish under the Marquis of Lansdowne, who created a new town plan in 1775. Almost a century later, in response to the dire unemployment and starvation conditions of the Great Famine, Kenmare became renowned for the superlative quality of its local handmade lace sponsored by the Sisters of the Poor Clare Convent. It’s still being sold today in the town’s Dickensian-flavored stores and exhibited in Kenmare’s Heritage Center and occasionally in the town’s remarkably eclectic array of fine restaurants.

JUST OUTSIDE TOWN AND across the bridge over the Kenmare River is an alluring sign pointing westward to the Ring of Beara.

“What d’you think?” asked Anne (already knowing the answer). “Go south to Glengarriff and then into Beara. Looks like a pretty wild drive over Caha Pass and through some rock tunnels. Or turn here?”

It was a larky-spirited no-brainer. To the south were ogreous tumblings of dark clouds over a hulking muscular mountainscape. The sun seemed hostaged in a tomblike fug. To the west, however, a narrow road meandered past tree-lined meadows into a misty haze of pearlescent light. Smoke-serpents curled languorously from the chimneys of small cottages…

So—west it was. And we congratulated ourselves on our choice as the light brightened and the wind-rippled surface of the bay shimmered in gold-platinum undulations.

The first few miles were mellowed by woods and copses, but slowly the trees thinned out and the shattered fangs and stumps of a far more ancient and broken terrain rose up through the winter-bleached swirls of moorland grasses. We passed a solitary standing stone locked in place by rugged drystone walls. Sunlight bathed its sturdy flanks in lacquered luminosity.

“That was a fast change of landscape!” said Anne.

“And just look ahead…,” I said, pointing toward an abrupt clustering of ominous bare-rock bastions rising precipitously out of the narrow, ocean-lapped plain.

“That’s our route…over those things!?”

“You’ve got the map. Do we have an option?”

“Well, there’s a road that seems to twist all along the coast, but it’s shown as one lane and not recommended for large vehicles…”

“We’re not that large…”

“You feel like playing around backing up on one-lane Irish roads with Irish drivers honking away at us…?”

“Not particularly,” I admitted.

“So—I guess it’s the mountains then!”

At least it was scenic—according to Anne. I wouldn’t know. My eyes were fixed firmly on each of the fifty or so switchbacking twists and bends that Irish drivers seemed to treat with glorious devil-may-care abandon. It didn’t make the slightest bit of difference that the road had two distinct (admittedly very narrow) lanes divided clearly by a solid yellow line. Most drivers seemed utterly oblivious to our presence as they wheelied around the bends way over on the wrong side, with tires screeching in Steve McQueen madness.

All this came as something of a shock, as I’d read the famous author John B. Keane’s eloquent description of Kerry and your typical Kerryman and expected a little more decorum and decency on the highways here:

The County of Kerry is distinguished by a gossamer-like lunacy which is addictive but not damaging. It contains a thousand vistas of unbelievable beauty…The Kerry attitude is spiced with humor and we tend to digress. To a Kerryman life without digression is like a thoroughfare without side streets…He loves his pub and he loves his pint and he will tell you that the visitor, no matter where he hails from, is always at home in the Kingdom of Kerry…Being in Kerry, in my opinion, is the greatest gift that God can bestow on any man…In belonging to Kerry you belong to the spheres spinning in their heavens.

You just can’t beat that Irish blarnied eloquence. And after such praise, I can only assume that the mad drivers were all from County Cork.

Lauragh came as a great relief. Not that there’s much to see here except the enticing subtropical exuberance of Derreen Garden. Like Kenmare, this was the outcome of another Cromwellian gift to a loyal British henchman, this time the conqueror’s trusted physician. And also, as with Kenmare, it came under the Lansdowne family’s control in 1866, which proceeded to create this masterpiece of a rhododendron and Australian and New Zealand tree fern estate in a moist, mossy microclimate on the south side of the Kenmare River. A perfect enclave in which to recover from the manic antics of those drivers.

We agreed to keep on driving westward down the peninsula toward Allihies and Dursey Island but were fully aware of a most tempting alternative. Right by the turnoff at Lauragh to Derreen Garden, a sign pointed toward the great granite wall of shattered Caha peaks and jagged purple shadows rising abruptly from wild swathes of boggy moorland. The sign read HEALY PASS and was cluttered about with warnings for narrow roads, dangerous bends, sudden climatic shifts, avalanche tendencies, and man-eating sheep. Sorry—slight exaggeration here. It was actually a warning that the sheep up on the high fells tend to regard the road as part of their pasturage and, particularly on warm days, enjoy sunbathing on the heated tarmac and are often reluctant to move, despite their possible imminent and messy demise. A more promising sign indicated great photo ops of Glanmore Lake, the barren bastion of Knockowen, the dramatic profile of the Iveragh ranges, and the majestic Macgillycuddy’s Reeks way to the north on the Ring of Kerry.

After Lauragh the low road scenery became distinctly less dramatic to the point where we both wondered if we should have chosen the Healy Pass route. Of course—as the seasons rolled on—we drove that wildly exhilarating sequence of serpentine switchbacks many times, deep into the high heart of Beara. We found it one of the most beautiful and dramatic drives in the whole of the southwest—a wild, empty landscape full of ghostly presences. But if we’d done that on this first day of our Beara experience, we’d have missed little Eyeries.

And little Eyeries should definitely not be missed, from its handful of traditional pubs and small stores (some great homemade sandwiches here) to the superb contemporary stained glass in the bright lemon-painted Catholic church. Of course, in a village renowned for winning national awards for “prettiest,” “tidiest,” and “most colorful” community, one expects to find not only a vibrantly hued church but also a whole village gone Fauvist color-crazy. Which of course it had.

“Gorgeous!” gushed Anne.

I must admit, I didn’t altogether share her unrestrained enthusiasm.

Quite honestly I’m not too sure about all these fairground regalias of colors found nowadays in most villages across the depth and breadth of Ireland. At first I thought—now here’s a quaint tradition reflecting the Irish love of jollity and gaiety. “Perky as a parrot’s plumage,” I scribbled in my notebook. But my initial impression was quickly corrected by an elderly gentleman near Skibbereen on the fringe of the Mizen Head Peninsula (southernmost of the five southwest peninsulas), who, with a wide smile and all the dancing-eyed charm of a bar-hugging raconteur, stated that “the whole damned place’s gone crackers with colors you’d only see on a baboon’s ass. Y’see,” he continued, “not so long ago it was all nice and simple—whites, beiges, grays, and maybe just once in a while a touch of canary yellow. More like cream, really. Double Devon, y’might say…”

“So why the change?”

“Who the feck knows. M’be they thought they’d got to compete with Italy and Spain for the tourist money…Or m’be they just got bored and wanted to liven things up a bit. Whatever—it’s got nothing to do with Irish customs and traditions. It’s just a load of tourist…”

“But y’know,” said Anne. “I like it. It seems to capture the Irish character. Colorful…and a little rambunctious.”

The old man paused and then smiled sweetly at Anne. (Many of them do. It’s something I’ve learned to live with.) “Rambunctious…tha’s a fine word…I never thought of it that way a’suppose…”

“Well—what’s the harm in it?” Anne continued.

He laughed a loud belly laugh. “Ach, there’s no harm. No harm at all—let ’em have their crazy colors…Life’s gray enough as it is!”

Well—that’s as maybe mate (old Yorkshire expression), but things were certainly not gray now in this little rainbowed village or across the surrounding smooth-crowned hills. The sun had finally graced us with its full presence. No more elusive hints of brilliance and warmth; no more pale light touching the tops of diffuse mists drifting in cupped bays of brittle, broken strata; no more rain-drippy cathedral-gloom naves of pines in the wooded places. Now we had azure blue skies and shrilling sunlight. Everything glowed. Cobwebs strung out among roadside bushes displayed beads of dew along their filaments, which flashed and sparkled like an Aladdin’s cave of diamond necklaces.

“Fickle, schizoid climate here,” I said.

“Maybe that’s why the Irish have this reputation for humor and an ironic outlook on life. If their moods changed as fast as the weather they’d all be bipolar manics,” said Anne.

“If you listen to Sam Beckett’s plays you’d think they already were…”

“I thought Beckett spent most of his time in France.”

“Well—sometimes you can see things more clearly from a distance…”

“Like those sheep ahead…which by the way are getting less and less distant!”

She was right. The pewtery sunlight was in my eyes and I’d failed to notice a fluffy family of Blackfaces settled comfortably in the center of the road and showing no intention whatsoever of making way for anybody.

“Stupid sods,” I mumbled, making a hasty loop around their sprawled forms.

Anne sat silently, smiling to herself, but I could hear every word she was thinking. And they were not very complimentary words.

HER SILENCE CONTINUED AS we entered a rather more trepidatious portion of our “Ring” drive. Our underpowered car struggled to grapple with a tortured terrain of ragged hills fringed with black precipices of broken rock, and a serpentining road barely wide enough for a single vehicle. Scores of threadlike runnels and streamlets chittered down the fractured strata, leaping off ledges in fanlike filigrees. The landscape possessed almost surrealistic Joycean images. I seemed to see slow-moving figures—great shambling forms—in the rock formations towering above the moor. There were crepuscular presences here. Then suddenly over a hump came a farm, compact and clustered up to the very road itself, and a towering white wall immediately ahead of us.

Anne gasped—her silence broken by an alarmed “Whoa!”

Where the hell had the road gone!?

And then I spotted it—disappearing around the corner of the farmhouse at an abrupt right angle. Brakes on. Skid and wriggle. Wait to hit wall. Wall vanished. Car made the turn all by itself. And then stalled. Facing a long uphill.

“Jeez!” I think I said.

“Ditto times ten!’ said Anne breathlessly.

“What a stupid bl—” I began.

“Well, look at it this way.” Anne is always the optimist. “A bend like this means there’ll never be any tourist coaches doing round-the-loop, Ring of Kerry–type excursions here on Beara!”

“Good point,” I agreed. “But a bit of a warning would have been nice.”

Anne smiled: “There was one. I assumed you’d see it.”

“How big?”

“Apparently the normal size for Ireland—’bout the size of your average dinner napkin!”

THE DRIVE NOW WAS truly serious. As the weeks went by this became one of our favorite parts of the peninsula—an adrenaline-stimulating rush of a romp through its wildest heart—a land of diminution of self. But our first introduction was just a touch too much on the precarious side. And parts of the problem were the glorious vistas that kept zapping our senses around every white-knuckle bend. Great glowing panoramas of purpled ocean, soaring cliffs, high moorland, the dark broken teeth of ridges draped with cloud-shadows, mountainsides seemingly torn by the claws of enormous primeval beasts, and that emerald shimmer of greens so richly varied and vibrant. You can’t help humming a chorus or two of “Danny Boy” and “Four Green Fields,” that amazingly moving anthem of cruel Irish history from the heart and pen of the late Tommy Makem—a man we were proud to know for a number of years before his recent death.

Anne spotted Allihies first. “Here comes another color-cluster village.” She laughed. And she was right. Eyeries possibly wins out in terms of the overall brilliance of its hues, but Allihies had selected a more modulated range of tones that blended well with the surrounding landscape. With one notable and renowned exception—the bright Venetian vermillion red of O’Neill’s Bar and Restaurant right in the center of this small, compact community. Little did we know how this beloved nexus of local craic, céilí, and occasional dance hooley with its roadside trestle tables, cozy bar rooms, and rather more elite upstairs restaurant, Pluais Umha, would quickly become a home away from home for us (along with the adjoining smaller Lighthouse and Oak pubs). Of course neither did we know at that point in our adventure that Allihies itself would also become the base for most of our time here.

O’Neill’s seemed a good place to pause for a ritual pint o’ the black stuff and, following the recommendation of a hiker sitting at an adjoining roadside table, two gargantuan platters of delicious fish ’n’ chips pub grub. All around the northern fringe of the village rose huge black cliffs pockmarked with shadowy tunnel holes. We later learned that this was the Puxley Family Kingdom, where an affluent Anglo-Irish family, the Puxleys, had put to good use their know-how from their Cornwall copper mines in the eighteenth century and made a fortune from reserves of copper and silver discovered here.

Of course most of the money went directly into Puxley pockets, and the local workforce of up to 1,300 men, women, and children were as powerless as penned hens and had to endure starvation wages, appallingly dangerous working conditions, and cruel crushings of even the most modest of their pleas for improvements. The Puxleys’ importation of skilled Cornish miners also caused considerable outrage locally, particularly as they were lured here by higher wages and even new comfortable housing in a villagelike setting up on the hillside by the shafts.

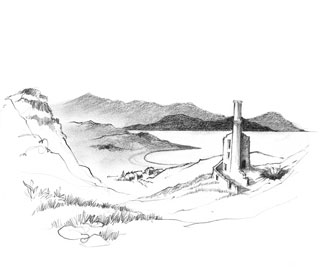

The ruins are still evident today, as are remnants of the old engine houses and the shaft holes. The main one, fenced off for safety, is an eerie invitation to a vast underworld of labyrinthine tunnels. All around the shadowy maw are turquoise-hued strata indicating the rich presence of copper. Such temptations have lured speculators into occasional and more recent reopenings of some of the mines, but so far the rumored “great vein” of undiscovered ore is yet to be found.

In later weeks Anne and I returned to wander the wild, broken terrain here. We also listened to the stories of John Terry in the local grocery store and tales whispered in the Allihies pubs of strange nighttime sightings of “things best not talked about…,” disappearances of “blow-ins” among the unmarked shafts, and spectacular “secret” finds of silver that one day might bring an instant Klondike of untold riches to this modest little village.

There were all kinds of other tales too floating around about the mines. One of our sheep farmer neighbors later told us about sacrifices of food and whiskey that used to be made in the mine to ensure against mechanical failures and accidents. Others told us about secret tunnels linking some of the shallower shafts with the ocean cliffs and used by smugglers.

On this first visit to Allihies we happened to meet Tom and Willie Hodge, owners of a farm near the village’s enticingly white sand beach of Ballydonegan. “Our pasture’s only thirty-six acres—with a lot of rock in it—and sixteen cows. Not much of an outfit really,” said Tom. “Ah reckon we must just like cows!”

Conversation with the two of them was made difficult by their unique accents—a sort of combination of Irish and what sounded like Cornish brogue. Apparently many of the people here had relatives who had come from the tin mines of Cornwall in the nineteenth century and had worked in the surrounding shafts.

“There’s still plenty of copper left,” said Willie. “If it gets to a good commodity price someone might try and open it up again. There’s always rumors—even about finds of gold and uranium—but there’s been no real interest in the place since 1967. They’re supposed to be opening a museum about the mines just up the road here, but the funds seem to keep running out. And they’ve spent quite a bit on the main engine shed up on the slopes there, but it’s so crazy-dangerous around the big mine hole—the one with all the copper streaks in the rock, great blue bands of it—that they say they may never open it to the public.”

Ballydonegan Beach and Allihies

Daphne du Maurier’s world-famous classic Hungry Hill is a pretty accurate tale of the Puxley family history here but with considerable added melodrama and geographic dislocation. (The actual Hungry Hill, at 2,260 feet the highest point on the peninsula and famous for its towering waterfalls, is almost twenty miles to the east near Glengarriff.)

Du Maurier’s description of the results of a “workers’ rebellion” here is typically evocative of her style: “The mines on Hungry Hill had ceased to work. The fires went out at last, and the smokeless stacks lifted black faces to the sky. The whine and whirl of the machinery was still. A queer silence seemed to call on the place. The mine had a deserted air. The door of the engine-house swung backwards and forwards on a broken hinge.”

The enormous Puxley mansion, described by one outspoken writer as “a grandiose pile and lump of gross ostentation,” was built a few miles east of the mines. It adjoined the tumbled remnants of the medieval O’Sullivan Bere Castle of Dunboy perched on a Norman-styled motte-and-bailey mound surrounded by ancient yews and huge splays of rhododendrons overlooking nearby Castletownbere and Bere Island. This must have been a sturdy and most imposing monolith if the ornately decorated gatehouse here is anything to go by. But in 1601 the O’Sullivans unfortunately sided with the Spanish against Queen Elizabeth I and were largely massacred. A heroic remnant of a thousand or so supporters led by Chieftain Donal O’Sullivan sought sanctuary hundreds of miles to the north in Leitrim but were largely wiped out on their terrible “long march.”

A couple of miles beyond Allihies, past that beautiful beach, and almost at the tip of the peninsula, a narrow lane leaves the main loop road and heads down through bosky, sheep-dotted hills. A sign reads DURSEY ISLAND and offers a rough handpainted timetable for the infamously tiny cable car contraption (the only one in Ireland) linking the peninsula with this tiny four-mile-long island. We made a mental note to visit sometime, little knowing what a ghastly Pandora’s box of cruel history we’d discover here. But that, as they say, is another story.

THE ROAD NOW SWUNG abruptly eastward as we began the second segment of our “Ring” drive, traveling along the southern shore of the peninsula by the broad, sparkling Bantry Bay. Moors and meadows suddenly opened out into truly majestic vistas. The land dropped away abruptly into small farms and grazings. To the south we could clearly see the last two of the five peninsulas of southwest Ireland—Sheep’s Head (very rural) and Mizen Head (celebrated by more discerning travelers seeking respite from the self-conscious charms of Cork, Cobh, and the Kinsale region).

Closer in we finally spotted the capital of Beara, the lively fishing community of Castletownbere nestled beneath the Slieve Miskish mountains and sheltered from erratic bay weather by the languorous green dome of Bere Island. This was once a major Royal Navy base when Britain and Ireland were united, until its closure in 1938. The British were most reluctant to leave what was generally recognized as being the largest natural harbor in Europe, and it took more than a decade to organize their final departure. Winston Churchill was particularly anxious to keep it as a base during World War II and even hinted at a return of Northern Ireland to the Republic—a deal that never materialized. Fortunately, around two hundred devoted residents have discovered what an enchanting hidden place this is (in the midst of the larger hidden place of Beara itself). It’s served by two regular ferries from Castletownbere, dotted with late-eighteenth-century Martello watchtowers; a Bronze Age “wedge tomb” thought to date from around 2000 BC; a prominent ten-foot-high standing stone; and remnants of British gun emplacements and forts, all still in surprisingly good condition.

Castletownbere itself (also once known as Castletown Bear-haven) is a pure delight, particularly in terms of sketch-worthy subjects when the huge, often Spanish and Portuguese fishing trawlers cram the harbor wharves here. But equally appealing are the more hedonistic aspects of life here—the town’s pubs, restaurants, and stores—and, for the truly overindulgent and overaffluent—the reincarnated Puxley mansion at nearby Dunboy Castle.

When we first arrived on Beara there were only rumors and whispers of bizarre schemes to reuse the shell of the mansion, destroyed by the IRA in 1921, long after the Puxleys had left and closed the disappointingly nonproductive copper mines in 1884. Many of the unemployed miners immigrated en masse at that time to Butte, Montana, and Beara families still maintain close ties today—including one moving and live video reunion we attended organized in Castletownbere.

Eventually plans were published for a $100 million “six-star” resort hotel featuring Ritz-Carlton management, and imaging itself as a “secret hideaway” for celebrities seeking solace from the ubiquitous paparazzi, a Michelin-starred restaurant, pools, luxury spa facilities, a vast wine cellar vault, and, naturally, a helicopter landing pad—even a special house for the colonies of Lesser Horseshoe bats that once occupied the ruined mansion. All were part of this very non-Beara type of project.

Some locals thought the whole venture was merely a clever “never-happen” gimmick to spur speculation in the proposed mini “leisure-village” developments on the peninsula—but apparently not. The project is now completed, and while rather alien to the “undiscovered” ambience here, its exclusivity, according to the developers, will ensure “minimal disturbance” to the everyday life of Castletownbere (“except m’be make us a little richer for a change with all those new jobs and whatnot” according to one of the locals here).

There’s none of this “starred” nonsense, however, in the restaurants and watering holes in town, most of which are clustered around or close to the main square. In addition to the now world-famous red-and-black facade of MacCarthy’s Bar and Grocery, it was reassuring to find a cornucopia of culinary delights in the form of O’Donoghue’s, O’Sullivan’s, Breen’s, O’Shea’s, The Copper Kettle (great soups and fruit pies), Murphy’s, The Hole in the Wall, The Olde Bakery, Cronin’s Hideaway, Comara, Twomey’s, and Jack Patrick’s, run by the local butcher and his wife and renowned for its traditional Irish cuisine. And then of course came the two hotels—Beara Bay and Cametringame, complete with their own bars and nightlife enclaves.

One of the most popular local dishes in the pubs and restaurants here is the ubiquitous Irish mixed grill. And according to the celebrated writer John B. Keane, this is the ideal list of key ingredients: “A medium-sized lamb chop, two large fat sausages, four slices of pudding—two black and two white—one back bacon rasher and one streaky, a sheep’s kidney, a slice of pig’s liver, a large portion of potato chips [French fries], a decent mound of steeped green peas, a large pot of tea and all the bread and butter one could wish for…authorities are divided as to whether fried eggs should be included or not.” So—there it is. A gourmand’s checklist to ensure no culinary short-changes!

And what a gourmand’s checklist of Brit-Irish goodies awaited us when we had a quick walk around the town’s compact and cluttered supermarket: crumpets, Birds Eye custard, Callard & Bowser’s butterscotch, sandwich spread, Marmite, HP sauce, treacle sponge and spotted dick in cans, piccalilli, jelly babies, Oxo cubes, Fry’s cream bars, Gentlemen’s Relish, Rolos, pickled onions, Lucozade, Robinsons Lemon Barley Squash, and on and on. Gorgeous!

For a community of fewer than two thousand permanent residents (itinerant Spanish, French, and Portuguese fishermen and “blow-ins” of all nationalities rapidly increase the population), Castletownbere was a true ceadsearch (sweetheart) of a town that gave us many memorable evenings of céilís and craic. On one occasion a barman showed us a descriptive clipping of the town dating back to 1920 with the comment that “ah can’t see as things have changed much in nigh on a century!”

Thirteen trawlers from Bilbao, Spain, arrived today and the streets were crowded with brown men, holy medals around their necks, deeply religious oaths on their lips, merriment and good nature in their eyes, bundles of silk stockings and bottles of lethal Iberian brandy under their jerkins. The stockings and the brandy they would barter for anything available. The dances in the hall beside the harbor were a sight to see. You wouldn’t know under God what country you were in.

Whatever country it is, it’s certainly going “green” rapidly and responsibly. In the grocery stores you pay a fee for every plastic bag you need; NO SMOKING signs are everywhere (despite the threatened bar-boycotts by petulant puffers), and just on the edge of town is one of the most sophisticated recycling centers we’ve ever seen anywhere. This is no simple triparate glass, metal, and plastic depository. Instead there are over twenty separate collection sections for four different oils; three different glass types; five different paper bins, plus special containers for “small computers,” “large TV sets,” aerosol cans, car batteries, domestic batteries, fluorescent lights, and even plastic bottle tops!

EASING EASTWARD OUT PAST the town’s modern hospital, a scattering of sedate B and Bs, a couple of enticing arts and crafts galleries, and a very appealing golf course overlooking Bantry Bay, we became increasingly aware of numerous small roadside signs for archeological sites.

“It says here in the local guide map,” Anne told me, “that ‘over six hundred sites have been identified so far on Beara, ranging from wedge graves, stone circles, and ring forts to ancient church sites and, at seventeen feet high, the world’s tallest ogham stone just outside Eyeries.’”

“And what pray tell is an ogham stone?”

“Just a minute—I’ve seen something…ah—here…it says, ‘There are over three hundred still existing in Ireland and they usually mark important graves…The vertical script carved into the stone consists of a series of twenty different incisions based on Latin. The notches represent vowels and the slanting or straight strokes are consonants. The words themselves are usually found to be old Irish and are considered proof of a literate society dating back at least to 400 AD.’”

“Fascinating.”

“Yes, it is. And y’know, there’s something really magical about this whole peninsula. You feel as if you’re being lured into a very ancient place—a place that was possibly much more populated in prehistoric times than it is today. Presences…I can sense them. Can’t you?”

I’m not normally very tuned in to such psychic nuances, but I had to agree with my ultrasensitive partner. There was definitely a sense of well-organized layers of historic occupation here—or maybe, as a friend of ours used to say, “a captivating casserole of primitive cultures.”

And if we’d read the guidebook a little more carefully we’d have realized that we were only a few miles from one of the most significant sites in southwest Ireland—the great Derreenataggart Stone Circle—a place we later came to know well.

We passed the great gray bastion of Hungry Hill with its famous seven-hundred-foot waterfall (Europe’s highest) fed by two small lakes, and laced with waterfalls following a sudden rainstorm over the Caha range. Tumbling streams cascaded down the deeply gullied, elephant-hide-like strata, then split and splintered into sheened silver cascades. At the base of the mountain they surged in peaty froth and fury and raged down narrow serpentining streambeds across the long slow slopes of brown-green moor. Whirling like out-of-control dervishes, the streams roiled around boulders bigger than Beara’s famous standing stones, ultimately surging under and occasionally over the coast road and out into the vast stillness of Bantry Bay. It was a most impressive sight, and we wondered at the fury of the storm as it ripped across the bare rock summit. That was not a place, we agreed, that we’d like to be.

The terrain then began to stretch itself languorously into a wider coastal plain dotted with farms and sleepy communities like little Derreen, Adrigole, and Tratrask. Once again we were tempted to turn inland and cross over the peninsula on the dramatic Healy Pass road but resisted, promising ourselves a more leisurely trip later on in the month. We continued along the coast road, past the impressive bulk of Sugar Loaf Mountain and—finally—down a long winding descent into Glengarriff, end point of our first “Ring” drive.

Like Kenmare, this is definitely a town of Victorian distinction and self-conscious promotion. It boasts fine hotels and restaurants for “main highway” trade on the dramatically tunneled Caha Pass road to Killarney and beyond. The pubs are plastered with signs for “authentic Irish folk music céilí evenings.” Souvenir stores do a roaring trade in everything from hefty Aran island sweaters, hand-carved shepherd’s crooks, and Waterford crystal to budget bins full of fluffy little toys with Irish Tom O’Shanter hats, dainty shamrock-decorated spoons, and the inevitable black T-shirts with prominent GUINNESS IS GOOD FOR YOU logos. This is no longer wild Beara country, but despite all the commercialism (and notorious plagues of summer midges), it does offer three distinct attractions. Perhaps best known is Garinish Island, locally called Illnacullin, where a quirky Gulf Stream microclimate of high humidity and almost subtropical temperatures enabled the creation of an internationally renowned Italianate “Garden Paradise” on a tiny island a short distance from the shore of Bantry Bay. This unique little masterwork of exotic flora and fauna was created around 1910 and later became a favorite hideaway for George Bernard Shaw, who according to local lore wrote much of his play Saint Joan here among the exuberant gardens and delicate architectural “follies,” while amused by the antics of seal colonies on the rocky shoals around the island.

An even more exotic creation is the nearby Bamboo Park heralded by a large Japanese gateway and offering meandering paths and bay vistas framed by explosions of bamboo groves and tropical jungle enclaves.

But perhaps the most enticing—and authentic—attraction here is the Glengarriff (or Gougane, which translates as “rugged glen”) Forest Park, a large swathe of rare native oak woodland that once covered much of Ireland. This was a favorite haunt of such celebrated authors as William Makepeace Thackeray and Sir Walter Scott, and today hikers and avid nature lovers can vanish for days in this vast scenic—almost subalpine—wonder world of wild streams, shadowy gorges, waterfalls, and a silence that is so refreshing after the in-season tourist crush of the town itself.

Signs at Glengarriff pointed enticingly southward to Bantry, a delightful market town (famous for the produce stands of local cheese makers and other artisans) arced around the eastern tip of Bantry Bay and watched over by the graceful Queen Anne–styled Bantry House, built around 1700 and home to an eclectic collection of art and ornate furnishings, and magnificent gardens. The two remaining southwest peninsulas of Sheep’s Head and Mizen Head are to the south, and then eastward are Skibbereen and ultimately Kinsale, Cobh, and Cork. All very tempting destinations. But Anne, as usual, was the one to return us to a semblance of normalcy:

“Excuse me, but I wish you’d stop dreaming of driving south. We’re here on Beara and there’s now the rather significant question of precisely where are we going to live!”

“Live?”

“A house, a cottage, a bungalow. Y’know, preferably near the ocean, near a village with decent pubs and a well-stocked grocery store, and…”

“Ah, yes…”

“Y’remember now? We’re got nowhere to live at the moment…like tonight, for example!”

“Well, the lady we spoke to on the phone said she had a couple of options…”

“Yes, that’s true. So how about if we turn around, head back to Castletownbere, and go and take a look at what she’s offering. They all seemed very charming on her Web site, but we need to go and check them out. Let’s go…it’ll be fun!” (Anne is always very convincing when she plays the role of trip coordinator.)

“Yes. You’re right. Check them out. Definitely. Great idea.”

No reply. But it didn’t matter, because I knew she was raring to set up a new home in a new place, with new places to food shop, new dishes to cook, and with who-knew-what experiences ahead.

And what the charming lady with the bungalows to rent had said to us about her properties turned out to be absolutely true.

Within a couple of hours we’d selected an almost brand-new fully furnished bungalow for a “just-affordable” rent close to that beautiful white Ballydonegan Beach just below Allihies. By sunset we were sitting at our outdoor picnic table sipping a fine fruity pinot noir together as the brilliant flare of evening light turned everything golden. Shadows eased slowly across amber grasses and we could hear the soft susurrus of surf on the sand and we were very, very happy, bathed together in tranquil splendor.

We had arrived safely on Beara, made our first “loop” journey, and were falling in love with the place already. And we still had months more to explore and learn all the nooks and nuances of this unspoilt “best secret place in Ireland.”

So—once again—Sláinte!