WE REALLY DON’T WANT TO LEAVE. Particularly on a day like this. After almost a week of miserable gray glop, our last morning of the spring season on Beara, and the dawn is crisp-clear. Within an hour, the sky is pigeon-egg blue dappled with tiny white curlicues of cloud. The Skelligs are there too, no longer playing hide-and-seek in the sea hazes, but bold and proud as galleons—seemingly close enough to us to stroke their razored, almost reptilian ridges.

The tall grasses along the stream are swaying in the faintest of breezes, the buttercups beaming with a gilded sheen, and the daisies virginal white and nodding like a happy host of behatted schoolgirls. (Forgive the overindulgent imagery, but I was feeling rather Wordsworthian that morning.) Behind us are the rugged remnants of the tin mines, the chimneys and stone-walled engine houses, broken and black against the brittle summits and strangely eroded flanks of the hills.

Over a fold in the half-moor of abandoned fields with their collapsing walls peeps the gaudy strip of houses, pubs, and shops of Allihies. The carnival cacophony of colors seems almost too blushingly self-conscious, especially as across the rest of the sweeping landscape bound by high ridges, most of the cottages and farms are demurely white or, at their most flamboyant, a delicate shade of lemony cream. This is a color echoed in the broad sweep of our sand beach, that unexpected bonus of copper ore tailings once washed down to the sea from the mines up on the hill. And then—of course—come the greens of the fields and pastures and inbye plots in a patchwork quilt of fervent late spring fertility. You could spend a year painting these and still not exhaust the patterned permutations of green in every imaginable tone and hue.

And as the sun begins its daily arc, the land seems to change shape constantly. The slowly moving shadows expose a welter of bumps and lumps that could be—and in most instances actually are—anything from ancient neolithic ring forts or stone circles to more recent ruins of the old “famine-era” houses, tumbled in tirades of wrath by avaricious eviction-lusting landlords or merely long collapsed through structural fatigue and the ever-increasing weight of sodden, mold-ridden thatch.

One thing is obvious from all these shadowy presences—this has been an active, well-used land, far more populous than today. And when the mists float across these bumps and lumps here and when the twilight blurs edges and diffuses things, you can often sense the soft sussurus, the eerie echoes of layered existences.

And we shall miss them—all of them. And we shall miss even the gray glop days when those proud Skelligs vanish and the unshorn sheep look like bags of rags scattered among the gorse and marsh grass. We shall miss our Beara. Very much.

And talking of the Skelligs—we shall also miss all those interludes and characters that brought so much depth, resonance, and humor to our daily adventures. For it was the Skelligs that were the key focus of our reunion with Seamus Gleason, whom we’d met in Dublin shortly after our first arrival in Ireland. He was a swarthy, bearded man somewhere “on the top side of forty—make that forty-five,” so he told us. He was also a fine raconteur with a rich brogue, and he promised to look us up when he made one of his occasional visits to the southwest. When he arrived on his first of two trips we happened to take him up to O’Neill’s in Allihies for lunch and a bit of sunshine on the pub’s outdoor tables, which crowded the roadside. By chance we were sitting next to a group of rather rowdy punkhaired youths from the north of England, and Seamus, with a sly grin, whispered to us: “Watch me stir this little lot up a bit…”

He cleared his throat, winked at us, and started speaking with a distinctly bombastic bellow. “So that’s how the story of the Irish saving civilization emerged: the Irish—we Irish—saved your whole bloody world, y’know!” said Seamus with a menacing laugh, inviting rebuttals.

There was a silence that was indeed pregnant at the punks’ table. But it was obviously one of those premature pregnancies—quickly followed by a gush of sprayed Guinness and a series of full ejaculatory exclamations.

“You bloody what?”

“Flippin’ stupid sod!”

“Crawl back to y’ bog, y’old Celtic clod!” (And other random pleasantries.)

Then silence. Until someone—presumably seeking to cast a little more fuel on this fire of furor—piped up: “Oh, well—pray, tell us more, Mr. Philosopher.”

I was expecting Seamus to raise a two-fingered gesture of dismissal and adjourn to a friendlier environment. But he didn’t. Instead he smiled an inscrutable smile and continued. “Yes, I will. I will indeed. When you gentlemen have piped down and shown yourselves capable of listening to a little common sense and a modicum of undisputed history. Not philosophy. But fact. Granite hard facts!”

More silence.

“Okay,” said someone else. “Cool it, lads. Let the man have his say.”

And his say was indeed worth saying. At least, Anne and I thought so. And the others certainly remained silent and semirespectful throughout Seamus’s intriguing discourse.

“No one, I don’t think, would ever link the word civilization with fifth-century Ireland…,” he began.

Nods and grunts all around.

“But if it hadna been for our little colonies of monastic scribes inspired by our St. Patrick, carrying the Gospel of Jesus Christ to this pagan wilderness in the fifth century and beyond, it’s likely that all the thinking and writing that had been collected in Rome from their empire, the early Judeo-Christians and the Greeks and the Egyptians and the Etruscans and many other wonderful cultures—all of it would have been torched and decimated by the barbarian hordes that sacked the Roman Empire and most other parts of Europe and Asia…and all would have been lost forever.”

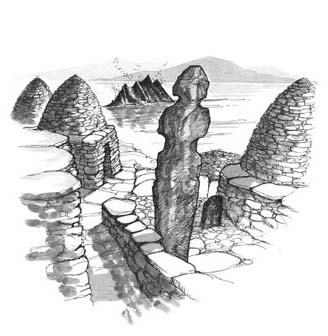

Seamus paused for a long swig of his porter and then smiled slyly at his (apparently) captivated, or maybe just confused, audience. “And all because these few righteous men could write and could copy and could then start to spread all these wonderful words and thoughts back to a broken, burnt-out Europe…and you’d know the kind of place that these remarkable men lived in…? D’y’know?” (“Behind Paddy O’Shea’s Pub on Limerick Street in Dublin!” said one wise-acre, but nobody even so much as sniggered. Seamus seemed to have this rowdy bunch in his hand.) “Where they lived was places like Skellig Michael off the Iveragh Peninsula—the Ring of Kerry. Go down the road here and you’ll see the island. A terrible broken pyramid of rock twenty miles off in the Atlantic. Seven hundred feet high where they had to climb seven hundred steps to their tiny little beehive huts—their clochans—made of dry-laid stones. And there they led lives of absolute asceticism, and for most of their relatively short and hard existences, scribbled copies of these books rescued from the pillaging and plunder of the barbarians…”

Silence. Until someone finally felt he had to challenge the adamant Seamus.

“So, you’re saying these little guys—these monks or whatever—stuck up on this rock and other places around Ireland ‘saved civilization’?”

“Well done!” said Seamus. “That’s precisely what I said. You’re obviously listening.”

“And so everything we see around today—books, libraries, universities, churches…all these things—they’re here because of these scribbling guys stuck on mountaintops and whatnot?”

“Yes—everything!” said Seamus. “Everything.”

“Makes y’ think,” said one young man, obviously impressed by Seamus’s ideas.

“Makes y’ thirsty too,” said another. “Whose round is it now?”

“Saol fada chugat! Long life to you all!” said Seamus with a wide grin.

“An’ now I suppose you’ll be expectin’ a pint too after all that history stuff,” said one of the punks with something like a smile.

“A splendid idea indeed, my friend—Bail ó Dhia is Muir duit.”

“An’ I bet that’s something really rude…”

“On the contrary—I am asking God and Holy Mary to bless you for your spontaneous generosity!”

AND THUS WISDOM AND insight is passed—or not—on your typical Friday-evening get-togethers at the local in Allihies. But Seamus had opened a little door of perception and insight in my head, and I decided to do some research of my own, starting with Thomas Cahill’s delightful book How the Irish Saved Civilization. And what I found was utterly intriguing and for the most part, reinforcing of Seamus’s basic premises. It seemed that tiny Ireland had indeed saved civilization as we know it. Cahill writes:

Had the destruction been complete—had every library been disassembled and every book burned—we would have lost Homer and Virgil and all of classical poetry, Herodotus and Tacitus and all classical history, Demosthenes and Cicero and all of the classical orators, Plato and Aristotle and the Greek philosophers and Plotinus and Porphyry and all subsequent commentaries. We would have lost the taste and smell of twelve centuries of civilization…All of Latin and Greek literature would almost surely have vanished without the Irish, and illiterate Europe would hardly have developed its great national libraries without the example of Irish, the first vernacular language to be written down…The weight of Irish influence on the continent [of Europe] is incalculable.

Cahill describes how, as the Irish monks and missionaries moved eastward from their lonely Eire outposts, proselytizing the Catholic faith, they also carried copies of “the great books.” In 870 Heiric of Auxerre, France, recorded that “almost all of Ireland, despising the sea, is migrating to our shores with a herd of philosophers.” Wherever they went, the Irish brought with them these books, many of them never seen in Europe for centuries…They reestablished libraries and breathed new life into the exhausted, virtually extinguished literary culture of Europe. “And that,” concludes Mr. Cahill, “is how the Irish saved civilization as we know it today.”

WE’RE GOING TO MISS these kinds of spontaneously bizarre episodes, but God willing and fate being fortuitous—we shall return in a few weeks, once the rush and crush of summer has faded. Of course we should emphasize that our beautiful, secluded peninsula bears few of the touristic burdens and the hullabaloo of holiday hordes that descend on Killarney and the Ring of Kerry, the next peninsula north. And the one after that too, the Dingle, which has increased dramatically in popularity in the last two decades. But even here—while our roads are far too narrow to permit the scourge of bumper-to-bumper tourist buses that plague the Ring of Kerry in particular—Beara seems to be attracting more and more discerning “backroading” travelers. So—we decided to share the bounty of our peninsula with others and offered our little cottage to them for a while. So they could enjoy the briny breezes, the infinite greens in our sheltered nook, and sunsets splashed like scarlet fire on the surrounding crags and ridges. We’ll come back when they leave—hopefully calmed and nurtured by this amazing place. Just as we have been.