AFTER THOSE INTRIGUING INTERLUDES WITH CORMAC and Rachael, we thought things were pretty much over for a while in terms of meeting prominent “creators” on the peninsula. But on Beara, as we learned over and over again, things are rarely over. Connections spawn connections, insights reveal more insights, friends create new friends, and the magic of spontaneous synergisms and synchronicities flourishes.

Rachael was strolling with us down through her Edenic garden to our car. “Oh, by the way, you’ll have met Tim, right?” she asked. “Tim Goulding?”

“No,” we said in unison.

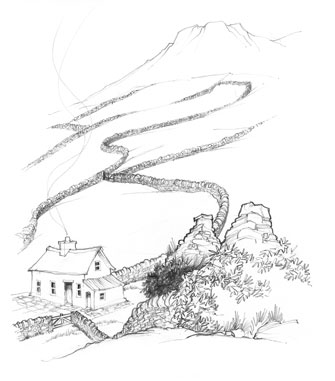

“Oh—ah!—well. That’ll be a nice surprise for you. He’s a lovely man—artist, composer, onetime rock musician—and another ‘cleft-dweller’ like us. Lives just up the road. Go to where it turns sharply to climb over the pass to Eyeries and take the rough track on the left. You go up a very narrow rocky valley—the house is painted blue and the garden is even wilder than ours…but it’s worth the journey.”

And so it goes. The serendipitous linking of creative spirits here who enjoy mutual nurture and nourishment on this wonderfully wild Irish finger of land.

Tim was home and didn’t seem at all surprised or irritated by our impromptu visit. Rachael had indeed been right. Here was another hand-built home secreted away in a deeply incised cleft in the strata and guarded by enormous upthrusting bulwarks of dark rock. And so dense was the junglelike profusion of small tiered gardens that the house and its outbuildings revealed themselves only gradually in coy surprises.

“And all this,” suggested Anne, “all this gorgeous exuberance, I imagine, gives you what Cormac and Rachael have found in their cleft—that sense of being utterly immersed in nature and inspired by it. From these tiny scatters of wildflowers and your enormous subtropical specimens to the sheer power of those bare rock precipices towering over everything.”

Tim laughed. “So, you know my work? My paintings?”

Anne was honest. “Actually, no. Sorry. In fact, I didn’t know of you at all until earlier on today when Rachael suggested we visit you.”

Maybe a little too honest, I wondered. But Tim was a man of grace, charm—and good humor. His face lit up in a huge smile and his long blond hair shook as he chuckled. “Great! Then I can brainwash you without fear of you quoting snide critics’ comments at me.”

“We are open books—scribble away upon our psyches!” I said.

So he did. We toured his remarkable home, admiring his airy studio and other spaces that seemed to appear as if by magic. Rooms flowed liquidlike into other rooms, and we had a sense of literally floating past large windows with dramatic images of Tim’s cleft-and-jungle topography and white-painted walls filled with a vast array of his own vibrant oils and acrylics.

Then in the corner of his studio I noticed a John Cage quote written on an index card and pinned to the wall. It read: “I can’t understand why people are frightened of new ideas. I’m frightened of the old ones.”

Tim saw me reading the card. “That’s great, isn’t it…such a waste of possibilities and joys,” he said, “the joys of endless discoveries of all the amazing creative and other selves we possess. Why would anyone not want to reach out and grab them all! What was it Bob Dylan once said—something like ‘a real artist has to be in a constant state of becoming.’ Great phase, that! Great reminder not to get too stuck!”

“Rachael told me you’d think something like that—and it reminds me of that other saying, can’t think who said it: ‘Creation is born of passion and reshaped anew in passion,’” I said. “She seems to see you as a true restless Renaissance man pushing out the edges in so many different ways…”

“Ah, Rachael and Cormac. Great, great friends. And constant inspirations. And I need that. I’ve always had a dread of getting stuck in a rut. It’s happened with some of my paintings. If I get into a new series and people enjoy them, then I’m offered these deadly commissions—you know, ‘Can you do me one just like that, but a…a little bluer to match my carpet!’ If you’re not careful you can become a sausage machine. Cormac fights the same battle with his ceramics.”

It was interesting to learn the coincidental parallels between Tim and Cormac. Both in their sixties, both living on Beara for over thirty years, both with prominent parents who gained fame and some notoriety from passionately pursuing their own unique lives. In the case of Tim, who was born in Dublin in 1946, his father was the noted businessman and art collector Sir Basil Goulding. “He was certainly what you might call a rather unorthodox figure,” said Tim. “On the one hand, a no-nonsense and nontraditional chairman of his own major business—he was also an avid and celebrated gardener, a great athlete, and a fanatical fast car driver. He and Valerie, my mother, gave me and my two brothers a wonderful upbringing by the River Dargle, which rolls out of the northern Wicklow Mountains. But—poor old Dad—he must have felt really let down when none of us wanted to take over the family firm. And especially with me—who kind of just disappeared into my own self-taught world of art and music. Although I think he would have sort of liked to live my kind of life—particularly the art part—so I guess I gave him a bit of a vicarious lift. Maybe!”

“What kind of music?” I asked.

“Oh, all kinds of weird stuff. I formed this group in the late 1960s—Dr. Strangely Strange. We had quite a bit of zany success for a couple of years. We still get together on occasion and create new stuff. I even did my own album in 2005—Midnight Fry. Remind me. I’ll give you a copy. It’s a real mishmash—a little bluesy, lots of dance-based loops, some great world-music-type multitracking. It’s best listened to with top-class headphones—takes you to another level…another wacko planet! C’mon, I’ll show you my recording studio…”

“You’ve got your own studio?” said Anne.

“Sure. I don’t use it as much as I should—but it’s great fun.”

Tim exuded a spirit of constant bemusement with himself, with everything around him, and the serendipity of the world in general. It was a contagious characteristic, and we found ourselves following him from surprise to surprise with permanent grins on our faces.

And there it was, another surprise, a small shed hidden atop a series of slippery, moss-coated steps up through the “jungle” and crammed with guitars, keyboards, speakers, and amplifiers, and a huge 140-track digital recording board.

“This looks like very serious stuff,” I said.

“Well—the art world has been good to me so…Oh, listen. Let me play you the first track of Midnight Fry—‘On the Fly.’ See what you think.”

Within seconds the tiny recording “shed” was shaking with a rich multitracked cacophony of sound. It was like being inside a gigantic stadium speaker. Incessant bongo beats merged with staccato loops in eerie echoing Philip Glass–type synthesizer sounds followed by Ry Cooder–type slide guitar infills. Tim passed me the CD box and it read:

Recipe for Midnight Fry: Stunning vocals, ambient soundscapes, chill-out interludes, cutting edge samples—all prepared in a bowl of World and Celtic spices by Ireland’s finest contemporary musicians.

“Can’t argue with any of that!” I shouted to Tim over the screaming speakers. He laughed and handed me a new copy. “Try the rest at home.”

“And what’s this other building higher up the garden?” asked Anne when the track ended and the little studio seemed eerily silent.

“Oh, that’s another recent project, a special studio for Georgina. My wife. Well—second wife, actually. My first lives just down the road. We’re still great friends. Georgina’s into aromatherapy and ‘essences.’ All rather mysterious at the moment—it’s a new business—but it smells so lovely in there.”

“Any other building projects?” Anne asked.

“Well—I’m tempted to expand my art studio a little more, but I guess I’d just be getting a bit too greedy. My mother had a great philanthropist’s spirit, so I get a little self-conscious about overly indulgent antics. She founded a clinic in Dublin for the physically disabled in the 1950s after that terrible polio epidemic. It’s a huge operation now. Twenty-five hundred people. And she was a fabulous fund-raiser, always putting on concerts in our home and having these great overnight guests—people like Grace Kelly, Albert Einstein, Peter Ustinov, Orson Welles. On and on. I never knew who I’d see wandering around in pajamas or who’d be joining us for breakfast. I even got a private lesson from Henry Moore once when I was just starting to paint. He advised me how to tackle three pots standing on a windowsill. I kinda got into this semirealistic, semiabstract, straddling-the-fence kind of mode. A way to express and appreciate a single image in different ways simultaneously, and it sort of stuck. One of my earliest series was Earth Fire. Very intense dramatic canvases inspired by the colors and ferocity of our ritual gorse burning in the fields and on the moors every year. C’mon, I’ll show you some of my stuff back in the house.”

And what a show it turned out to be. The gorse-burning works seemed to possess almost demonic energy as huge scarlet flames writhed up from the black earth into a black sky. Others portrayed the powerfully bold and broken landscape around the Allihies hills and the old tin mines. “There’s so much inspiration right here—in this fantastic place. Huge rock massings, vast ocean and skyscapes, islands, pounding storms, platinum sunsets, the wild loneliness of the moors. Then you come right down to the fantastic miniature worlds of lichen patterns on worn strata, the primordial darkness of the old mining tunnels, the timelessness of our standing stones, circles and souterrains—it’s all pure magic. And always with that underlayer of mystery…that sense that there’s so much more to see and understand. I mean, I’ve learned so much since 1969 when I bought this clapped-out cottage for virtually pennies, but there’s so much more now, so much…”

“But after all that time can you still see all this?” asked Anne, pointing to the vast vista outside one of Tim’s huge picture windows.

“Oh, yes! Oh, my God, yes! I mean, there are times when familiarity can drift in like a fog, but it soon lifts—burns off—and it’s all fresh and full of meaning again. It’s not all positive, though—the reality of this hard place. I mean if I wrote what I know—truly know—about Beara or even just this one tiny part, I don’t think I’d be able to live here anymore. There are still feuds and vendettas here going back decades—centuries! Depression is a scourge too, and the occasional suicide. Deirdre Purcell caught some of that in her famous book Falling for a Dancer. They filmed that for TV just over the top in Eyeries village. If you go to Caskey’s pub, you’ll see photos of the production. And Deirdre’s such a fine person. Lives some of the year just outside Eyeries on the Kenmare road. She’s a great lover of Beara—told me once she thought it was ‘one of the last places in Europe where everything is possible—and in a very relaxed and mellow way.’ I like that idea. It reminded me of the old man who lived in that tiny stone cottage just down the cliff here. He had this magnificent view over Allihies and the whole bay and out to the Skelligs and he’d spend hours on an old chair by his door, sheltered from the winds. He’d just sit and look and sit and look…closest thing to a true Zen monk we had on this tiny corner of the peninsula, although he’d have no idea what a Zen monk was! I think his silence and utter peace inspired me—and it sort of crept into some of my work…”

“But not into your music, I don’t think!” I said. My ears were still ringing from the traumatic barrage of Tim’s music mix in the studio.

He laughed. “No, I guess not. That’s another universe. It was a collective thing. Everyone wanted to be on the tracks, and there were over twenty-six musicians involved at one time or another. In fact I have a guy coming over tomorrow night—a wandering monk—he plays the Apache flute. Made from cedar—very unique sound. He’s laying down a track for a new piece I’m pulling together—stop by if you want. Oh, and while I’m thinking, don’t forget that just down the road toward Eyeries you’ve got Leanne O’Sullivan, one of Ireland’s very best young poets. Beautiful girl. You both should meet her. And then there’s John Kingerlee farther on. House near Deirdre Purcell’s place. Has a reputation for…shall we say…bluntness, but he’s a very talented guy. I’ll call them if you like. Let them know you’re floating about…”

AND SO WE FLOATED about—buoyed by the spirit of great active creativity on this amazing little hideaway peninsula.

And Leanne was, indeed, a beautiful young woman. We found her a few days later at her family home overlooking Eyeries and the great mountain mass of Carrauntuohill rising high over Macgillycuddy’s Reeks and the Ring of Kerry. At that first meeting it was the colors I remember most of all. The bright lemon of the O’Sullivans’ large house, the vibrant intensity of the green fields dropping down the long, slow slope of the land from brittle ridge summits to the surfy reefs and bays of the coast. Then came the almost red-golden richness of Leanne’s long hair, her soft but intensely luminous blue-green eyes, sprays of ginger freckles on her face and arms, and her pale, almost translucent skin. Dante Gabriel Rossetti or John Millais would have whisked her off to their pre-Raphaelite studios in the mid-1800s and immortalized her in one of their highly mannered, laconically moody, meticulously detailed masterworks. (I merely managed a scribbled sketch.)

Today, while only in her early twenties, Leanne has become accustomed to her celebrity as a gifted young Irish poet. “It began so early on, I couldn’t really get serious about it. I was only a child when the English teacher brought this well-known Cork poet, Thomas MacCarthy, to our class. He read some of his works and then asked if anyone would like to share one of their own poems. And there was this deathly hush. Everyone sitting there like stone statues, hoping they wouldn’t be picked out. So the teacher turned to me, and I could have fainted. But I’d been writing quite a few poems around that time, so I got up—knees all quivery—and recited one. And it seemed to go down all right. The class gave me a bit of applause, and then Mr. MacCarthy was very sweet and asked, ‘Did y’ ever think about gettin’ y’self published?’ I sort of looked at him like he might be a little crazy and I said, ‘I’m only twelve!’

“But I guess the idea stuck—the idea of getting some of the poems published. Much later I got involved with Sue Booth-Forbes at Anam Cara—her center for writers and artists just down the hill from here. She’s a beautiful altruistic person—a real creative catalyst—always helping others. My mum—Maureen—works with her, organizing workshops and special events. I’ll be doing a reading there in a couple of weeks—come if you both have time. Sue would love that. Anyway, I was only sixteen or so and working on new poetry and I got one published in Poetry. Then I started entering all these various regional and national competitions and winning quite a few awards. Part of me couldn’t take it all in. Things were happening too fast, and I was still just this skinny teenaager. In fact, I was very skinny—actually anorexic. So—well…here…this is a copy of my first book published a couple of years ago when I was twenty-one. It sort of gives you an idea of where I was at that very strange time…”

Leanne handed us a copy of a small paperback with a very black cover and a photo of a girl half-naked in a hospital gown with her back to the camera sitting on a heavy wooden chair with a strange ghoulish mask propped up against one of its legs. The title of the book was Waiting for My Clothes. Anne and I read the summary and reviews on the back cover together.

Leanne O’Sullivan was born in 1983 in Cork and is currently studying English at the University College Cork. Her poems have been published or given many national awards when no one knew her age… Waiting for My Clothes traces a deeply personal journey, from the traumas of eating disorders and low self-esteem to the saving powers of love and positive awareness. [Leanne summarized the essence of her poems:] “I was writing down the reasons I should live for and then became addicted to looking at things to find beauty in them.”

Billy Collins, the celebrated American poet laureate, was full of adulation: “Of course she’s far too young to be so good! She dares to write about exactly what it is to be young. A teenage Virgil, she guides us down some of the more hellish corridors of adolescence with a voice that is strong and true.”

And Selina Guinness, who celebrated Leanne in her 2004 The New Irish Poets book, wrote: “This voice seeks its own history in the most difficult terrains of the psyche; anorexia, sexuality, the loss of innocence; but resurfaces to discover afresh a world new and strange in images of startling perspicacity.”

One reviewer suggested that Leanne “writes with a visceral frankness about what it is like to be young in Celtic Tiger Ireland. The unabashed eroticism of her new work reestablishes a continuity with an earlier phase in Irish literature stretching way back to the pre-Christian sages.”

Another reviewer sought to place Leanne in a modern-day societal context: “The social revolution which has occurred in Ireland in the last two decades has made the youngest generation feel as if their immediate predecessors were raised on a different planet…Irish poets are today easily influenced by poets from elsewhere, in a way that is even more invigorating in this globalized world than it was in the ’60s and ’70s.”

Anne handed the book back.

“No, no—it’s yours,” said Leanne. “Please, keep it. I’ll sign it, if you like.”

“Thank you so much,” said Anne. Then she became very quiet as she scanned the first two poems in the book. Finally she smiled:

“Leanne—this is going to be a rich experience reading this book. You seem to love to…to ‘zoom.’ A line like—‘I see myself in the well of her pupil’—that’s a wonderful image!”

Leanne giggled. “Is that what that is—a ‘zoom’?”

Anne laughed. “Well, that’s what David calls it when he suddenly goes from a typical wide-angle view of things when he’s writing to a tiny image or microcosm, just like a camera zoom lens.”

“Great word.” Leanne chuckled. “I’ll use that!”

“So, what’s the current project? Another book of poetry?” I asked.

“Oh, yeah! So many things. Beara is still a very important element in our family lives. This is my father’s family home here. I’m always discovering new things. For example, just up a track there behind the house is a secret place—an unsigned secret sad place. It’s a place of unsanctified ground where they used to bury babies who died at childbirth or before they were baptized. According to the Catholic church, they went to limbo, where they’d never ever see the face of God. Little tiny innocent babies buried, unrecorded in any book—only in the hearts of their families—with only small rocks for gravestones in a cold cruel field called a Ceallunach. It’s such a horrible idea—although, thank the Lord, they’ve stopped it now. The new pope has declared that there’s no such thing as limbo anymore! But Beara is full of secret places like that. The Hag used to be a secret too. You know, that rock just outside Eyeries? It’s become a bit of a pilgrim site now and the folktales are getting all jumbled up. But I love anything with links to the ancient pagan power sources—fertility, harvests, mortality, and of course, immortality—the tales that once made the poetic oral traditions of Ireland so renowned in the Celtic world. Poets were regarded as seers, magicians, healers, second-sighters—sometimes the equal of bishops and even kings. We’ve got some of that in our own family—the ability of second sight. We don’t talk about it much, though. You’ve got to be careful. The old superstitions and fears are still floating about. Some have been Christianized a bit and some of the old power’s gone out of them—the things you read about in The Book of Cailleach and Gearoid O’Crualaoich. But I’m working on a set of new poems now about The Hag of Beara, and I find, even as I write, there are unfamiliar and powerful energies flowing through me.

“Yeah, I know it sounds a little odd, although—like I said, I do tend to be a sucker for superstitions and these ancient stories. But certainly I find the feminine in me is strengthened—made prouder—the more I seek out the power and the links between the tough women of Beara and the mighty female goddess inside The Hag. The church has tried to play all this down—but the older Beara women know how to weave a Celtic knot pattern of these stories. Especially about Bui—another name for The Hag, but also for The Cow—symbol of everlasting life.”

Our conversation grew increasingly fascinating. Both Anne and I could sense a different mood in the house, in the room, where we sat overlooking Kenmare Bay. And then Leanne began, without any fanfare, to read some of her new and soon-to-be-published Hag poems in a quiet voice full of restrained energy and fire. We just sat silently. Leanne had told us that her mother had problems listening to these poems—they made her blither (weep). One of them seemed to be having that same impact on Anne. But we still sat there and sensed The Hag almost as a tangible presence around us.

It’s only an old and not very big chunk of rock on an empty hillside, my skeptical, pragmatic self declared.

No, no. It’s the ultimate soul of Irish folklore—the indomitable feminine, the very essence of fertility, the underlying strength of the land and of the soil, my ancient Celtic self insisted. And this young woman, this walking-talking pre-Raphaelite portrait of beauty and insight, will be the one to reconnect all these ancient forces with modern-day mores and perceptions.

We left Leanne, wishing her that traditional Irish good night—oíche mhaith duit—to which she laughingly gave the traditional response gurab amhlaidh duit. Anne thanked her again, and I noticed she was clutching her book very tightly against her chest like a totem.

JOHN KINGERLEE LIVED IN a cottage of interlocking rooms and spaces. It was located at the side of the road to Kenmare—almost in the road—but buffered by a tall thick hedge that blocked the fine vista across Kenmare Bay. The place was artistically chaotic—books everywhere, scattered canvases, newspapers, things piled up in corners. And John was a different kind of individual altogether from any other artist I met on the peninsula—zanily irascible, opinionated, bloody-minded, rude, even a little crude, but gloriously honest and open.

Our meeting began with an initial request. “Hi—take your shoes off, please,” and I found myself looking at a small wiry individual, someone who seemed like he could throw a pretty mean punch and you’d never see it coming. His face was long and wolfish. Within seconds of our exchange of hellos I sensed a distinct aura of pent-up fury in the man—or at least a hefty dose of frustration—that might explode like a land mine if an unsuspecting stranger happened to step in the wrong place. His eyes were like little dark hard pebbles that darkened even more when he flung out one particular remark at me—fast as a throwing knife—after I thought we were having a pretty amenable let’s-get-to-know-one-another kind of chitchat.

“Quite frankly, David—I don’t think I agree with a single thing you’ve said so far…”

“Oh—sorry about that,” was about the only inane response I could come with at that particular moment.

“…although I certainly do envy you your certainty…”

I couldn’t suppress a chuckle. Most people, friends included, tend to accuse me of constant devil’s advocacy. Always testing out new ideas and trying to see things from different points of view. This accusation of certainty and implied dogmatism was altogether new to me. I have difficulty making up my mind finally about anything. Playing with options is invariably far more intriguing—and fun.

“I’m gonna take that as a kind of backhanded compliment and…”

“You can take it any way you bloody—”

“Yes, yes—I’m sure. So that’s what I’ll do as you tell me the story of your life. In a nutshell. So to speak.”

“In a nutshell?”

“Or anything else that’s small, compact…and with edges!”

“With edges?!”

“Yeah—edges.”

Kingerlee looked at me again with those oh-so-dark, almost feral eyes. He was either about to explode—or laugh. Thankfully, he laughed. “In a nutshell. Okay. Here we go. Born Birmingham, England. Spent time in London. Dad a manager of some kind of poker club. Started painting at three (me, not my dad). My Auntie Anna looked after me—her boyfriend was Douglas Fairbanks Jr. Went to a very Catholic boarding school. Did odd writing and poetry projects and learned to paint in the furnished bedsit where I lived. The place drove me nuts, so I painted like mad and began to find patrons and buyers. Christy Moore, the famous Irish folksinger, bought a lot of my stuff in those days and that helped. Got deeply into Jung. In the 1960s lived in Ibiza and Cornwall and then dumped all that eventually and lived in Morocco, Fez, and Tangiers—and became Sufi. Changed my life completely, inside out and upside down. Now I live here part of the year since 1982. My main patron is a fine guy—Larry Powell—who buys most of my work. He helped me publish a very fancy retrospective book—big coffee-table format—on my art.”

“And how would you describe your art?” I’d seen an odd mix of his pieces since my arrival. Some were scattered across a table between piles of art books. Some were framed on the walls. Others were in various stages of completion—strange collages of images, haunted multilayered portraits thick with still-moist paint…These did not appear to be happy works. Apparently I was right.

“My portraits are layered alienations…I particularly watch the faces of politicians and so-called world leaders. Maybe that’s where some of my portraits get their sense of cynical presence from. One of my favorite works is a canvas that got partly chewed up by a cow. She gave it real texture and a sort of unique 3-D tactile energy! I don’t know why these portraits are popular—maybe it’s that they’re kind of iconic. But also very human. Some have taken over a couple of years to complete—a slow accumulation, layer upon layer of paint, but each one quick and spontaneous. And most are not people I know—except the self-portraits. Even Christy Moore said he recognized me from those portraits. But then I’m into the ‘squares’ paintings—kind of restrained classical grids and little tiny abstracts. There’s a whole mix of stuff—some are very extrovert and flamboyant.”

I’d done some homework on Kingerlee before my visit. Anne is a whiz with the Internet, and the Internet is a whiz with instant information. So all I have to do is say something along the lines of “Darling, I wonder if you could just tap out a nice fat ream of stuff on…” and she’ll smile her bewitching kind of smile and the stuff would pour out in nanoseconds. Kingerlee has obviously garnered a host of admirers around him and his works. One critic compared him (favorably) with Mark Rothko; another claimed his thick, stratified landscapes, with sometimes up to a hundred overlayers of paint, as “a richness beyond compare.” Art critic John Benington gushed that “he re-creates spaces that we could enter mentally and visually in a way that seems to have no parallel in contemporary art…His work literally frizzles with energy as if seen through the eyes of a child…creating a unique cosmic world.”

One writer suggested that Ezra Pound, Paul Klee, Jean Dubuffet, and Jean-Michel Basquiat were key influences on his work and that “anyone privileged enough to watch him paint is struck by an analogy with gardening—He tends the grounds of his pictures with the same devotion as a gardener.” Apparently his key implements are palette knives (often one in each hand) and large decorator painting brushes.

Unfortunately I was not “privileged enough” to see the man in action, but there were other things I was curious about—most notably what I tend to label as “The Vivaldi” approach to creativity, where similar themes and arrangements recur again and again in a string of different works.

“Did Sufism lead to any changes in your art?” Ever since John had mentioned his sudden conversion, I’d sensed he’d wanted to tell me more.

“Oh boy, yes—although it’s hard to be specific. In fact, it’s difficult, actually, to recall what I was like before I became Sufi. But I’m very much involved in their world—their explanation of our mutual integration in a web, a vast web of connections. If I suffer from anything now, it’s me as a Muslim in a non-Muslim world. I’m particularly skeptical, as you may have gathered, of paternal institutions like the World Bank, the IMF, and the mindless damage they do and the corruption and horror stories they generate. I’m also very skeptical of ‘New Age Business’ in general. It can be so insular and greedy. It needs to be ‘cleansed.’ [Ironically his words were highly predictive of the financial calamities that arose round the world a year or so later!] Proponents of it should celebrate the month of Ramadan instead—you lose some of that glib civilized veneer, and by your daily fasting, you learn—you’re reminded—what it’s like to be poor every day of the year. When you remove the prestige of food and drink, you become much more humble and vulnerable. You also begin to recognize that you don’t really exist, and neither do I. It’s a long explanation…but, well, on the Night of Power toward the end of Ramadan—for those who are open to it—your identity becomes like a wave of light, and you hardly exist at all. It’s as though the heavens open and Allah sends down his messengers and his knowledge.”

It would be impossible to recollect all the meanderings and abrupt direction-shifts of our long and wide-ranging conversation. Fortunately, however, my loyal little tape recorder whirled and whirred away in my pocket, and I picked up a remarkable range of Kingerleeisms over the course of our first two-hour meeting. I include a random selection:

“I’m seventy and I’ve been vagabonding most of my life, but on Beara I found myself in the footsteps of the Celtic revival artists and everything changed.”

“I’m seventy and I’ve been vagabonding most of my life, but on Beara I found myself in the footsteps of the Celtic revival artists and everything changed.” “I want fewer and fewer things and an ever-enlarging life.”

“I want fewer and fewer things and an ever-enlarging life.”  “I’m really only interested in people who are trying to promote tolerance, empathy and understanding.”

“I’m really only interested in people who are trying to promote tolerance, empathy and understanding.” “The World Bank and the IMF and a lot of the ‘do-good’ organizations are ironically great stiflers of compassion. They kill millions of people a year with their financial structures and terrible burdens of usury. I’ve lost a lot of friends arguing about all this.” [His argument reminded me of Ezra Pound’s outrages at the scourges of bankers and “international finance.”]

“The World Bank and the IMF and a lot of the ‘do-good’ organizations are ironically great stiflers of compassion. They kill millions of people a year with their financial structures and terrible burdens of usury. I’ve lost a lot of friends arguing about all this.” [His argument reminded me of Ezra Pound’s outrages at the scourges of bankers and “international finance.”] “The more ‘good’ things you do, the more ‘bad’ things you end up creating. You know, that old chestnut ‘No good deed ever goes unpunished’! Or that other one: ‘Every action creates an equal and opposite reaction.’”

“The more ‘good’ things you do, the more ‘bad’ things you end up creating. You know, that old chestnut ‘No good deed ever goes unpunished’! Or that other one: ‘Every action creates an equal and opposite reaction.’” “Poor old USA. It’s damned if it does and damned if it doesn’t. The world always turns to the USA in any crisis—and then sits back and sneers and criticizes while the USA tries to respond—which it normally does pretty badly.”

“Poor old USA. It’s damned if it does and damned if it doesn’t. The world always turns to the USA in any crisis—and then sits back and sneers and criticizes while the USA tries to respond—which it normally does pretty badly.” “Amateur ‘artists’ wait for inspiration. The rest of us rise up every morning, splash our bodies, and get down to hard work.”

“Amateur ‘artists’ wait for inspiration. The rest of us rise up every morning, splash our bodies, and get down to hard work.” “Picasso was a great rediscoverer. Sometimes I think I’d like to ‘reinvent myself every day,’ like he suggested all artists should do. But I also like boundaries. Limitlessness can lead to insanity. But so can success! Picasso also said ‘Of all the things God sends you—poverty, injustice, hunger, lack of recognition—fame is the hardest to deal with’!”

“Picasso was a great rediscoverer. Sometimes I think I’d like to ‘reinvent myself every day,’ like he suggested all artists should do. But I also like boundaries. Limitlessness can lead to insanity. But so can success! Picasso also said ‘Of all the things God sends you—poverty, injustice, hunger, lack of recognition—fame is the hardest to deal with’!” “The best joy of life is spontaneity—to be a slave to the second!”

“The best joy of life is spontaneity—to be a slave to the second!” “Some of us can go back mentally—believe it or not—to their very first feast on the rich milk from their mother’s breast…You get an amazing sense of where we all come from when that happens.”

“Some of us can go back mentally—believe it or not—to their very first feast on the rich milk from their mother’s breast…You get an amazing sense of where we all come from when that happens.”As with Tim and Leanne, I left John Kingerlee much later than I intended. It had been a remarkable few hours. At times I felt we had skirted the edges of malicious minefields and the possibility of actual physical confrontation over economic and social issues. But then there were moments of great warmth, and the whole experience ended almost blissfully. It reminded me of a paraphrase quote of Kurt Vonnegut’s—“There’s only one rule I know of here on earth—Goddamn it, we’ve just got to be kind to one another.”

John was even gracious about one of my earlier books—Seasons on Harris. I brought a copy to show him what I hoped to produce on Beara. He studied the book and its illustrations very intently, and I was preparing myself for another of his verbal assaults. But instead he looked at me, smiled a truly genuine smile, and said, “David, I’m envious. I couldn’t do what you’ve done here. The artwork is particularly beautiful.”

That, I thought, deserved a handshake and a hug and I reached out to grab him. He suddenly looked startled—almost afraid. Then he explained. “So sorry—it’s Ramadan. I can’t…”

“Oh,” I said. “I’m sorry too. I didn’t know.”

“Don’t worry, even my wife, Mo, can’t touch me during Ramadan. But I owe you one when it’s over next week.”

I haven’t had that hug…yet.