“TODAY IT’S DEFINITELY VERY HIP TO be Celtic,” said Ralph White with an ironic chuckle that shook his stocky frame and made his thick beard and long mane of dark hair jiggle. He had joined Anne and me up at our house in New York State during one of our return trips from Beara, and he was quoting a line from his remarkable work in progress, At the Edge of Cultural Change, a memoir he’s been slowly compiling over the last five or so years.

Ralph and I have known each other for well over a decade, although our actual face-to-face meetings have been far too few. As a community member and organizer at Findhorn, that world-renowned mystical “garden-commune” in northern Scotland, a former program director of the Omega Institute in Rhinebeck, New York, and cofounder and creative director of the world-famous New York Open Center in Manhattan and a myriad clones, Ralph has been deeply involved in the evolution and devolution of holistic, ecological, and spiritual thinking throughout the USA and Europe. His current editorship of the online magazine Lapis is now sending out even wider ripples of knowledge and insight across the planet.

I told him that I thought the At the Edge part of his book’s title was far too modest and diminished his amazing role as creator-catalyst of new ways of thinking, understanding, and living. In Deep, I suggested, might be a more appropriate title, but Ralph, a Britisher with Welsh-Irish blood, resists any insinuation of self-congratulation and hyped-up promotion.

I tried to persuade him to join us on Beara, but the demands on his time and energy from emerging holistic centers around the globe never allowed us to settle on a date. His spirit, however, was well and truly present, particularly his deep fascination with the Celtic world and its labyrinthine web of legends, mythology, and ancient wisdom. “The Celtic soul is far more prominent now in the world today than ever,” he told me, his eyes alive with enthusiasm.

Ralph has met and often befriended just about every major and celebrated proponent of holistic spiritual thinking and life-ways on earth. I found it fascinating that a man who has organized seminars, workshops, and conferences involving scores of these individuals—Christian scholars, yoga masters, Tibetan Buddhists, Kabbalists, Zen Roshis, Taoists, Native American medicine men, Amazonian shamans, and Sufiphilosophers—would ultimately return to the roots of his own ancient Celtic culture to find the depth, resonance, and perception he has been seeking for decades. He has managed to condense a vast diner-sized menu of philosophical and spiritual options in to a far more modest and balanced repast. He has journeyed long, hard, often dangerously—and invariably penuriously! In fact his odysseys of discovery—his inner discoveries particularly—began as a child: “I lived within a few hundred yards of the Irish Sea and went to school in tram cars that traveled through wide open fields to the shores. The mountains of Snowdonia to the south were visible through our kitchen window, and the patchwork of pastures, hedges, and hills stretching inland expressed a magic mixture of harmony and wildness that brought great joy and excitement to my child’s soul…I was always moved by the cry of gulls. What was it that touched my little soul so deeply in this most common, but also most evocative, of bird calls? Years later in Ireland it came to me that what I heard dimly, echoing as if from some ancient past, was the lost holy wisdom of the Celtic island saints. As a child I knew nothing of them, but as an adult I became an aficionado of Celtic sacred islands off the coast of Scotland, Wales, and Ireland.”

But all that was only after Ralph’s “wonder years” of wandering from Central and South America and Machu Picchu, Eastern Europe and Russia, to some of the remotest and dangerous regions of Tibet, the Celtic centers of Europe, and the “ancient alchemical world” of Renaissance Bohemia.

In between his journeys, described with great vigor and verve in his still incomplete memoir, Ralph was involved in founding and/or organizing three major catalysts of holistic thought and action, which attracted a vast spectrum of thinkers, practitioners, and participants. Ralph was deeply enmeshed in not only the mundanities and minutiae of creating organizations but also the miracles of megachange and transformation that he sensed emerging from these amazingly energetic and effervescent centers.

But somewhere deep in his own soul and in the mind-boggling mélange of philosophies and “isms” he’d studied, he constantly sensed around him the great archetypal figures of Welsh mythology, Merlin and Taliesin—both beloved shamans with knowledge and understanding of the deepest mysteries of nature. “They were always present,” said Ralph with his soft voice and irrepressible grin, “reminding me—and all of us—of the earth wisdom we need as we so belatedly attempt to restore a sustainable earth.”

“But surely they’re figures of myth—not reality?” I said.

Ralph’s gentle grin became a chesty guffaw. “Well then—they’re in good company with all the mythical Greek gods from whom we draw so much insight and wisdom—and even the Creator Himself/ Herself/Itself and dozens of other legendary figures who function as metaphors for our own growth and enlightenment. The Celts had a natural affinity for altered states of consciousness—an intuitive acceptance of shape-shifters, magicians, and fairies. Merlin and Taliesin were all part of that wonderful tableau. I mean, the Celtic world possesses a panoply of mythical figures, but it also has an intrinsic soul very much linked to reality and the earth itself. I discovered that truth in the 1970s when I spent time on the island of Iona in the Scottish Hebrides, long famed for its sanctity as the birthplace of Celtic Christianity. It was here on this wonderfully wild and windswept place that St. Columba came from Ireland in the late sixth century and carried with him a pure, nature-infused spirituality to the wild Scots and Picts who had remained beyond the control of the Roman Empire, north of Hadrian’s Wall.”

Ralph sat quietly for a while, smiling at his memories. “Iona’s a truly magnificent place—a primeval haven with spirituality permeating the rocks, cliffs, caves, fields, waters…It’s everywhere. Alive and throbbing. I enjoyed some of the most perfect, soul-nourishing experiences of my entire life on this little holy island. I don’t have much interest in organized formal religions, but here I sensed an ancient spirit of true sanctity that felt eternal and essential…I sensed the island offering itself as a sublime location for the deepening of spiritual life. Certainly my spiritual life and, from what I know, the lives of tens of thousands of other seekers.”

Another pause and then: “I mean…the feeling of peace and strength and delight I used to get just standing on top of Dun I, the island’s highest hill. Late summer afternoons on cloudless days gazing west across that turquoise ocean—I can still remember those sensations of utter calm years and years later. And if I ever sense tensions or anxieties, I return to Dun I in my mind and let those beautiful memories restore that sense of inner peace.”

“So the Celtic heritage still has real power even today?” I asked.

“Oh my gosh yes! And not in a theme park nonsense way, and not among esoteric—or more likely fake—crystal channelers and the like. I honestly feel that the Celtic mysteries still possess a power that can rival anything that’s emerged out of Tibet or India or Native America, or anywhere else, for that matter. And—as you know from living on Beara—the west coast of Ireland is a Celtic wonderworld brimming over with gods like the Celtic sun god, Lug, a whole array of Celtic-Christian saints, hermits, poetic bards, storytellers, folk healers, seers, shape-shifters, healing shamans, magicians, heroic kings, wizards, Druids, mighty warriors, banshees, and shee fairies—the Tuatha Dé Danaan—the spirit of Wicca, and neopaganism—all living on the fringes of Tír na nÓg—the ‘Land of Eternal Youth’—that otherworldly paradise. And even during the early centuries of Christianity when hermit-monks lived on those remote western Irish isles like the Skelligs and Caher—Celtic traditions and mythology often linked with Arthurian and Holy Grail legends survived intact.”

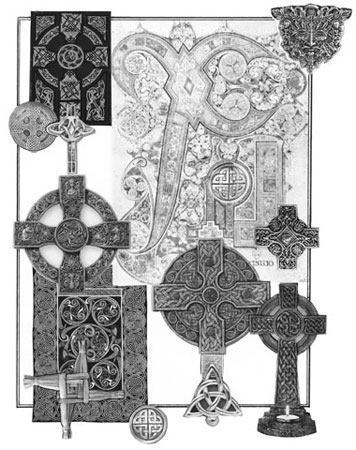

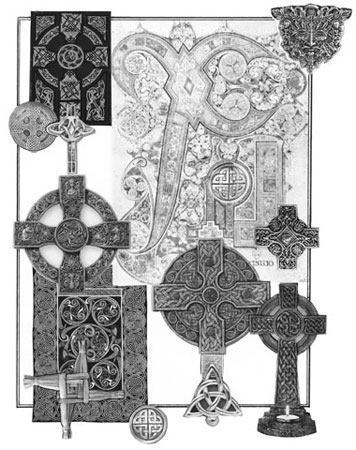

A Collage of Celtic-Christian Symbols

“Even today?”

“Yeah, well, it’s like I said—it’s hip to be Celtic today. Look at all the neo-Celtic music—all that Riverdance craze—movies like Braveheart, lots of Celtic-revival bands, new interest in the Celtic languages themselves, and all the great legends and song-poems. Sometimes, though, it can get very distorted. Until the recent peace in Northern Ireland, paramilitary groups on both sides would use the figure of Cuchulain as their own icon, the warrior-hero of that great song-poem The Cattle Raid of Cooley—in their initiation rites. One of the problems is that in their legends the gap between the Celtic bloodthirsty warrior culture and their deep, nature-loving spirituality was very narrow—almost invisible. And yet its essence is very human—recognizable in its strengths and frailties. It’s easy to identify with. I think that’s one of the reasons for the survival of Celtic traditions—that and maybe a deeper attunement to the wisdom and beauty beneath the surface of the Christian tradition. It’s tremendously life enhancing—it binds you very strongly. Whenever I’m in Europe and need stillness and inspiration away from all the crush and stress of cities, I’m off to the Celtic lands and islands. Places of natural silence. Places to rediscover deep and enduring threads of connectivity with all the essential elements of life and living.”

There was silence for quite a while. “Well, I guess that pretty well sums it all up,” I said.

“Yep. I guess it does…for now.”

“So all that’s left is for me to get hip and get Celtic…”

“Right”—Ralph laughed—“and also recognize just how subtle Celtic ideas were about the unity and balance of man and nature. St. Brigid, one of the most revered Celtic deities, is still a symbol for appropriate ways of interacting with the natural world. You could argue she was in contemporary terms a real ‘Greenie’—an avid supporter of conservation, recycling, reduced consumption, and increased sustainability by stopping our mad pursuit of mutual self-destruction.”

“So I guess you could claim that, in the midst of our overwhelming consumer capitalist culture, the Celtic spirit seems to stand for something way beyond obsessive materialism?”

“Absolutely,” said Ralph in a voice that sounded distinctly adamant and absolute. “It evokes a sense of music, soul, and poetry, of ‘the other world’ beyond the mundane chores of existence. I think we yearn for this desperately in the midst of all the money, gadgets, and obsession with work that characterize contemporary America. James Macpherson’s poem Ossian, which evoked the heroic world of the ancient Celtic warriors in the highlands of Scotland, had a huge impact on the emerging Romantic movement at the end of the nineteenth century. As Europe was evolving from the rationality and classicism of the Enlightenment, it was this Celtic world that offered inspiration to figures as diverse as Goethe and Napoleon, both of whom were great admirers of Ossian. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, during the time of the Celtic revival and the work of W. B. Yeats, Irish myths and fairy tales summoned magic into an increasingly commercialized and industrialized world.”

“So today the Celtic archetype returns once again to summon up the deeper mysteries of the Self?”

“Oh yes—to remind us of the need for a society in tune with the natural world, which stands for imagination, intuition, and mystery at a time when our psyches are barraged with an ever greater volume of data, trivia, and noise. As we see so many becoming gormless slaves—slaves of fleeting fads, slaves to the meaningless opinions or judgment of others, even slaves to the search for self-gratification and godless ‘self-fulfillment.’ As our longing for silence and beauty inevitably grows stronger in the face of this relentless stream of shallow stimulii that characterizes the early twenty-first century, the Celtic world reminds us of different and far more enduring values and a different form of consciousness. It certainly seems to me that the lure of those sacred islands, the pull of those holy places, the fascination with an ancient but living culture imbued with soul and spirit—all these will only grow stronger as the human psyche demands a new wholeness with the power to create a far more sustainable and increasingly just world.”

Another long pause.

It seemed all that needed to be said had been said—elegantly and emotionally—by Ralph.

But then I think I surprised my friend: “Okay, I guess I get the last word because I’ve been doing some reading too. So I’ll offer you a blessing based on the wisdom of the Celtic ogham—that ancient alphabet that possessed special spiritual qualities: ‘May the trees of the forest take root in your heart that you may grow in wisdom, joy, and love for all who live in the earth’s embrace.’”

Ralph looked a little surprised. Then he smiled, and then he gave one of his big laughs, which made me realize what a great experience we could have had together if I’d ever managed to lure him down to Beara.

“Maybe next time.” He chuckled.

“Yeah…maybe.”