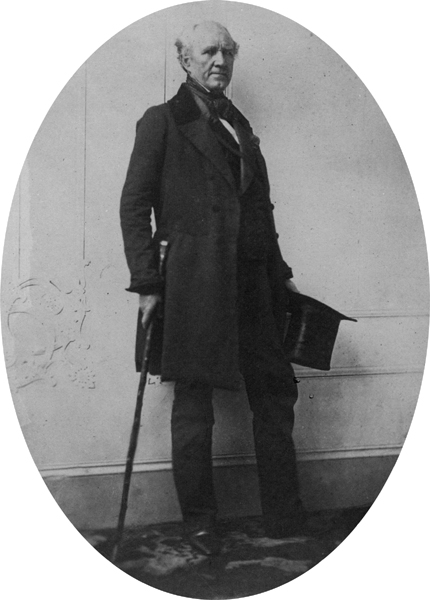

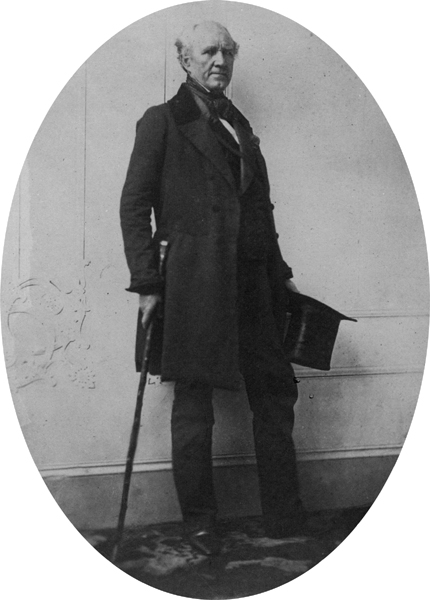

Despite his hopes for a quiet family life, Sam Houston could not give up his political career. In 1859, he was elected governor of Texas again. The aging politician posed for this portrait in 1855.

Sam came home in March 1859 after finishing his term in the Senate. All he hoped for, he wrote, was to be with his wife and children. He said he would raise sheep and cattle on his Cedar Point farm. Margaret noted that his limp was worse.

The quiet life ended all too soon. The sight of an old foe running for governor was too much. Sam jumped into the race. Short of funds, he ran without party backing. He made only one speech. In Texas, that was enough. His name was still magic.

The Houstons arrived in Austin in December. The governor’s mansion, they found, had been stripped of furniture. The state had to spend $1,500 to make the place livable. Even then, the family was crowded into four upstairs bedrooms. A seven-foot, four-poster bed gave the new governor room to stretch out.

Despite his hopes for a quiet family life, Sam Houston could not give up his political career. In 1859, he was elected governor of Texas again. The aging politician posed for this portrait in 1855.

Sam spoke out against secession. Texas, he said, “entered not into the North, nor into the South, but into the Union.” To fight the drift toward civil war, he proposed a better use of the nation’s strength. The United States, Sam declared, should annex Mexico. Doing so, he said, would “improve our neighborhood.” Better still, the North-South conflict would end as slavery spread south. Border raids by Mexican bandits gave added force to Sam’s argument. The nation, its mind fixed on the slavery issue, ignored his plan.

The desire to be president still drove Sam. As the election year of 1860 dawned, “Houston men” rallied to his cause. Their support pleased Sam, but it was not enough. The parties met, debated, and picked other men. Calling himself the “people’s candidate,” Sam stayed in the race. He spoke out for Southern rights—but only within the Union. Electing Abraham Lincoln, he thundered, would lead to civil war. It was not long before Sam saw that he was hurting his own cause. Rather than split the anti-Lincoln vote, he withdrew from the race.

Lincoln won the election. As Sam had forecast, South Carolina quickly left the Union. More slave states followed. The rebels formed the Confederate States of America. Would Texas follow the same path? In February 1861, delegates met in Austin. They declared that Texas was part of the Confederacy. Sam opposed the move, but he had few allies. Given a chance to vote on the issue, Texans favored secession three to one. On March 15, state officials were ordered to swear loyalty to the Confederacy.

Sam Houston will forever be remembered as a hero in Texas. One of the state’s largest cities bears his name, and monuments to him can be found all over Texas. This statue welcomes visitors to Hermann Park in Houston, Texas.

Sam did not sleep that night. In the morning, he said, “Margaret, I will never do it.” When the moment came, he was as good as his word. While his fellow officials took the oath, Sam slipped out of the room. A clerk called his name three times. Sam did not respond. Friends found him in a basement room, whittling. The convention promptly replaced him with a new governor.

Two weeks later, the Civil War began. Stooped and white-haired, Sam offered to serve with the Rebels. His offer was turned down. Sam, Jr., joined the Second Texas Volunteers. He fought bravely until he was wounded at Shiloh. The Bible in his pocket absorbed much of the bullet’s impact, very likely saving his life.

By 1863, the Southern cause was failing. Sam’s health was no better. In July, a cold turned into pneumonia. His breathing grew labored. Family and friends crowded close to say good-bye. On July 26, Sam spoke for the last time. “Margaret! Texas … Texas!” he muttered. Moments later, the hero of San Jacinto was dead.

That night, Margaret opened the family Bible. She wrote, “Died on the 26th of July 1863 Genl Sam Houston, the beloved and affectionate Husband and father, the devoted patriot, the fearless soldier—the meek and lowly Christian.” She knew her man. Sam could not have asked for a more fitting epitaph.