WSM never passed on a chance to promote itself. Although the park was years away from opening, WSM took out a full-page advertisement to attract attention to both Opryland and the new Grand Ole Opry House.

Two

THE HOME OF

AMERICAN MUSIC

WSM never passed on a chance to promote itself. Although the park was years away from opening, WSM took out a full-page advertisement to attract attention to both Opryland and the new Grand Ole Opry House.

On May 21, 1972, an estimated 3,500 invited VIPs gathered on Opryland USA’s 30-acre parking lot to hear 45 minutes of speeches to dedicate the complex before a sea of red, white, and blue balloons filled the air high above the Cumberland River. Dignitaries at the event included Tennessee governor Winfield Dunn, Congressman Richard Fulton, and Nashville mayor Beverly Briley. The special soft opening of the park was only for Opryland’s corporate parents, WSM, Inc. and the National Life and Accident Insurance Company; the media; and government officials. G. Daniel Brooks, chairman of the board of WSM, told the audience that Opryland USA was the end result of company history that started 47 years ago when “Uncle Jimmy” Thompson sat down with his fiddle in front of WSM’s microphone. By the time the sun set, officials estimated that 12,000 visitors had entered the park. One week later, the park would officially open to the public at 10:00 a.m. on May 27, 1972. (TENN.)

The grand opening of the park was planned be a giant media event, similar to the openings of Disneyland and Walt Disney World, including a prime-time network special that showcased the park for the nation. Timex presents Opryland USA aired May 30 on NBC, three days after the official opening of the park. Hosted by Johnny Cash and Tennessee Ernie Ford, with special guests such as Danny Thomas and Minnie Pearl, the program highlighted the park’s entertainment, ranging from country to pop. Prime-time network specials continued to showcase the park until 1996.

Since approximately 25 percent of the park existed in the deep woods, it was decided early on that the park’s maples, oaks, pines, cypresses, and dogwoods would be a strength rather than a hindrance. Two giant tree-moving machines worked 15 hours a day to transplant 4,000 existing trees. According to Mike Downs, the park’s first general manager, almost 100 percent of the original trees on property were saved.

Ben Moore, the park’s landscape manager, developed a temporary tree nursery, complete with existing bird nests, to add plant life to the complex. There were 400 additional dogwood and magnolia trees to mingle with the natural tulip poplar, honey locust, black cherry, and sweet gum trees.

In the first year, there were 18 seasonal and 9 permanent employees hired solely to tend to the flowers and plants, as well as the five acres of lawn grass. In addition to the multitude of trees, 1,000 hanging baskets were mounted, 150 whiskey barrels were arranged, 100,000 annuals were placed, 1,000 bushes were set, and 1,200 tulips were planted. As seasons changed during the operating year, 20,000 flowering plants would rotate in as the year progressed.

Upon entering the Opryland USA complex, one would have been immediately surrounded by the antebellum-inspired architecture of Opry Plaza. The area was free to the public, open year-round, and full of museums, ticket booths, gift shops, food stalls, and, by 1974, the Grand Ole Opry House.

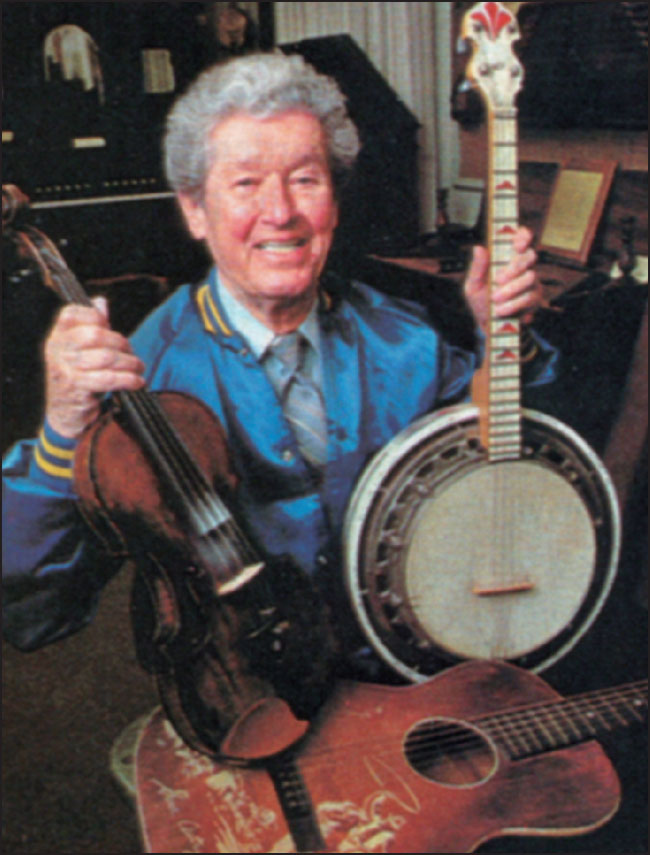

One of the first attractions announced for Opryland was the Roy Acuff Music Hall. Acuff had previously owned a similar attraction near the Ryman Auditorium in downtown Nashville. Acuff had saved memorabilia throughout his rise to fame and collected rare mementos from other celebrities as well. Included in the attraction were artifacts such as the fiddle that Acuff used to record his number-one hits like “Wabash Cannonball” and “The Great Speckled Bird.” Other instruments included Mother Maybelle Carter’s autoharp and Little Jimmy Dickens’s guitar. The museum’s prized piece was Uncle Jimmy Thompson’s fiddle, which was played on the first radio broadcast of the Grand Ole Opry. Years later, Minnie Pearl opened a similar museum. Even later, Roy Acuff and Minnie Pearl shared a larger museum together in the former Southern Living model home.

The National Life Hospitality Center in Opry Plaza served as both guest relations for visitors and as a theater venue for the 20-minute “Great Moments from the Opry.” The multimedia show highlighted America’s country music heritage. Guests could also obtain information about handicap-accessible shows and rides, check a park-wide message board, upgrade tickets to a season pass, exchange Canadian currency, and check for lost and found articles.

After entering the turnstiles, the first area to the left was Hill Country. In its initial years, it was also known as Appalachian Village or the Folk Music area. However, the theme remained consistent—visitors could see real craftsmen at work; enjoy real authentic country food, such as biscuits and molasses; and listen to the roots of country music. Additionally, the park’s first breakout ride, the Flume Zoom, called this area home. (Author’s collection.)

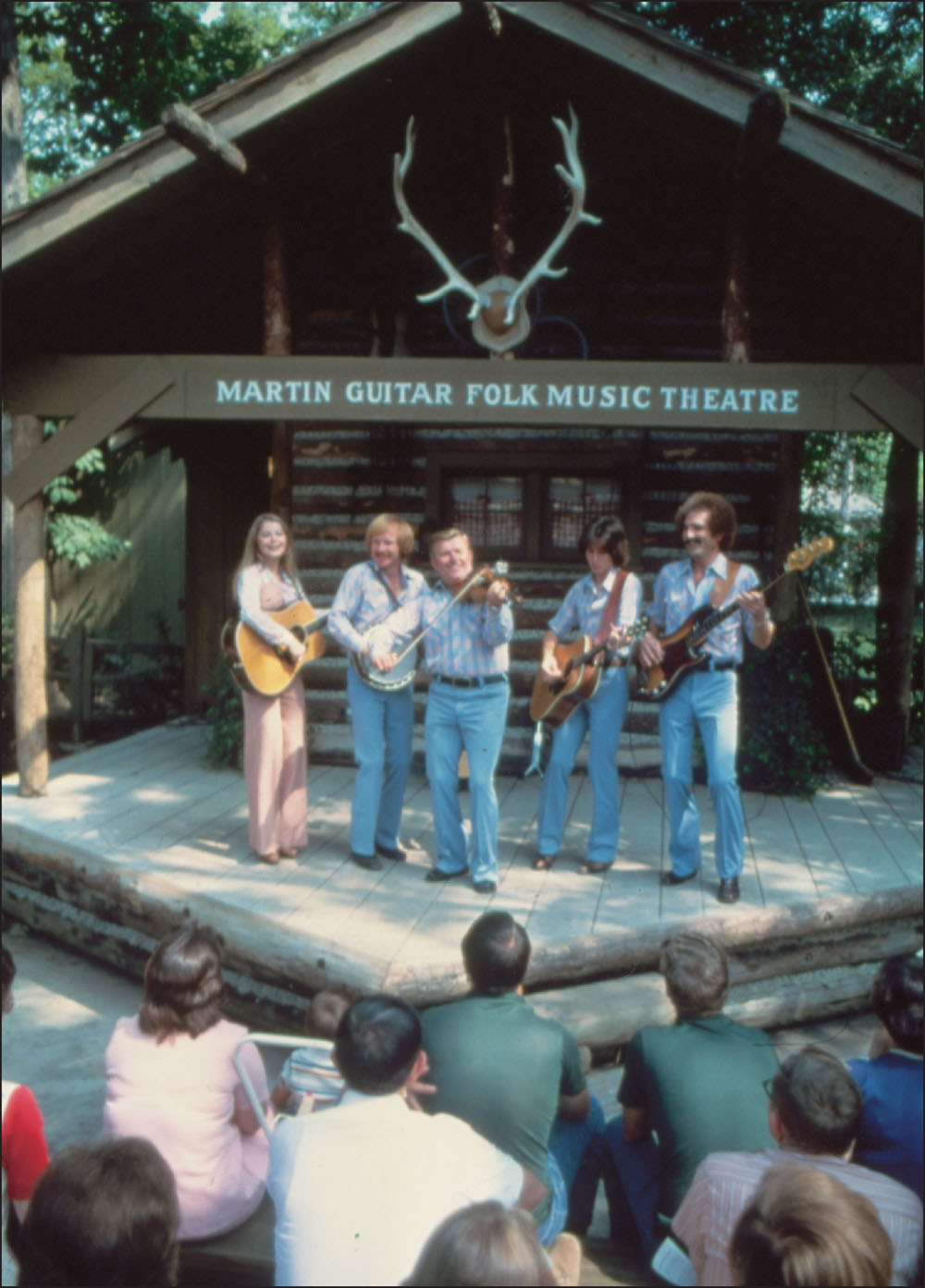

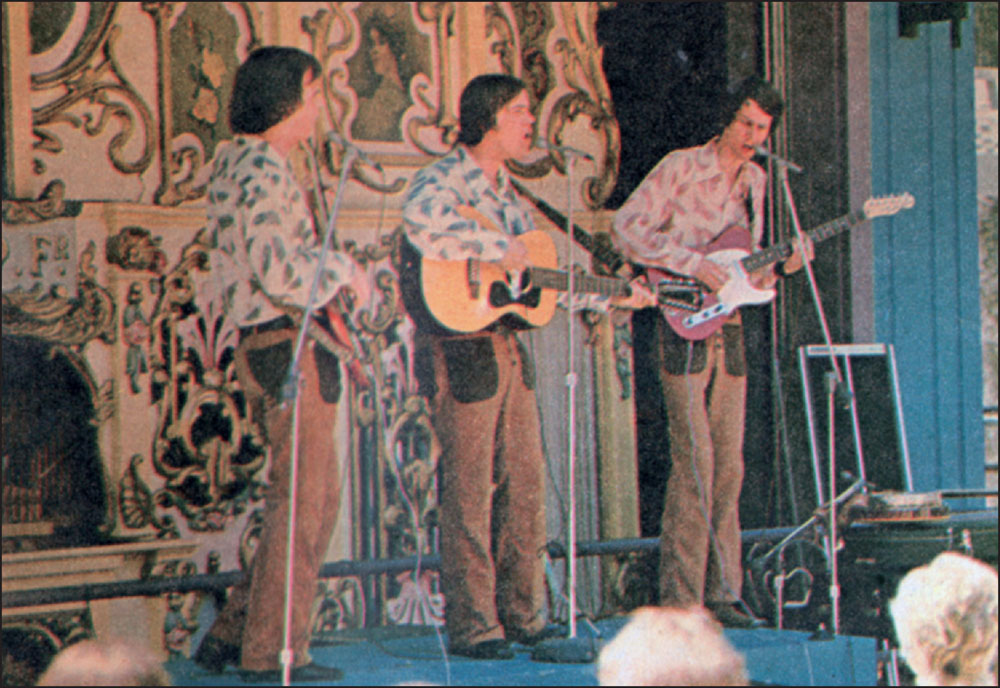

Originally sponsored by Martha White flour, the C.F. Martin Guitar Folk Music Theatre featured several recording artists, such as Mack Magaha and Russ and Becky Jeffers. The 425-seat amphitheater came alive with down-home sounds of bluegrass and mountain music. The pickin’ and singin’ seemed as natural as the outdoor theater’s rustic benches.

By the 1990s, the park’s focus had shifted to the visitors’ desire to meet the stars and celebrities of country music. The Hill Country area was renamed Opry Village, and Grand Ole Opry stars were made available for autographs and pictures every day the park was open. More importantly, the celebrities could now participate in daily shows at the Martin Guitar Folk Music Theatre.

In Hill Country, Opryland visitors could see a real potter working away at a potter’s wheel, a woodworker’s bench and loom, candle-making demonstrations, or a craftsman making musical instruments for sale. Other trades on display included carvers, glass engravers, and sign makers. Elsewhere in the area, WSM-AM had broadcast facilities that produced a weekly show from the park. Years later, both WSM-AM and WSM-FM would move their entire facilities to the theme park.

Opryland’s Flume Zoom captivated the imagination of its guests from opening day. Designed by Arrow Development, the attraction was similar to the log flumes used by lumberjacks to move their logs from the hillsides to the river. Unlike similar log flumes that floated at ground level at other theme parks, Opryland’s flume was almost entirely 75 feet in the air. Eight pumps propelled 28,000 gallons of water per minute through the flume and then down the 90-degree drop. In 1979, as part of a sponsorship agreement, the attraction was renamed the Nestea Plunge. After the promotion ended, the Flume Zoom title returned for a few years until the ride was christened Dulcimer Splash in the 1990s. The flume was slightly altered in 1984 to accommodate the Screamin’ Delta Demon, which had its track built around the ride supports and surroundings. (Both, Michael Parham.)

The Opryland Railroad was a loop of a three-foot gauge track that connected two stations, El Paso and Grinders Switch, inside the park. The total length of the railroad was slightly less than a mile. During the park’s first years, the railroad consisted of two authentic steam trains. The trains ran daily with either one or both trains, depending upon attendance. The original cast-iron sign from the real Grinders Switch, home of Minnie Pearl, located near Centerville, Tennessee, was placed near the front of the station. (Michael Parham.)

There were two stations for the Opryland Railroad: Grinders Switch and El Paso. Both stations were of similar design with a central enclosed office area that led to open-air covered waiting area on each side. The El Paso station was situated in the American West; whereas, the Grinders Switch station was located in the Hill Country.

As attendance climbed, Opryland Railroad’s stock grew to three locomotives: Beatrice (No. 1, later renumbered to No. 4 after diesel conversion), Rachel (No. 2), and Elizabeth (No. 3). Beatrice, a steam-powered locomotive, was later converted to a diesel/hydraulic engine in the park’s later years. Rachel was a steam locomotive as well, but Elizabeth was an original train built especially for Opryland. She had a diesel/hydraulic engine replica that had the outline of a steam engine and resembled the park’s other two trains. (Both, Michael Parham.)

There were eight coaches, each having seats that faced both directions. Two of the coaches were designated as end units, with an elevated seat for the rear train host. All three locomotives had decorative “loads” of wood visible to imply that they were wood-burning steamers.

Unlike other parks with singing animatronic animals, early Opryland press materials stressed the real, live nature of the new park. The Animal Ravine was a short lived attraction that debuted with the park and led visitors along a wooded area bordered by the Cumberland River. Visitors could walk through the area on paths that created the impression of being surrounded by animals. The attraction was designed by Jim Fowler of television’s Wild Kingdom. More than 500 animals were in the ravine in 1972, including lions, bears, wolves, buffalo, beavers, and other animals in their natural habitat.

The Opryland Railroad had its own dedicated maintenance building, with a two-track engine house that consisted of a rectangular green metal structure with roll-up doors on each end. The dead-end tracks inside the engine house featured pits below the tracks that allowed for working on the underside of the engines and coaches. In 1980, the track closest to the main line was extended past the end of the engine house in order to assist the conversion of Beatrice from steam to diesel. Fueling the locomotives was done along the main track instead of the engine house. All engines used No. 2 diesel fuel, and an elevated water tank provided treated water for boiler use.

Right around the corner of Hill Country was the New Orleans area. With 12 structures, New Orleans had the most buildings of any of the lands when the park opened. There was coffee brewing and Cajun specialties cooking. The grilled ironwork dripped like black lace from a French Quarter balcony. There was also a Dixieland show, a flower mart, an artist alley, a glassblower, and a magic shop.

“American music is real as the blisters on a man’s hand behind a blow,” said Mike Downs, Opryland’s first general manager. The architecture in the park, especially in the New Orleans area, strived to achieve that realness. The buildings used bricks, cedar shingles, and whitewash instead of fiberglass, steel, and theatrical set paint found at similar theme parks.

The Dixieland Patio theater served as the centerpiece for the New Orleans area. Several shows called it home, including New Orleans Jazz. It featured the sounds of Scott Joplin, Louis Armstrong, and other Dixieland greats who gave America its own special kind of music. From Dixieland jazz to rhythm and blues, the New Orleans Jazz show made visitors smile, clap their hands, and tap their feet.

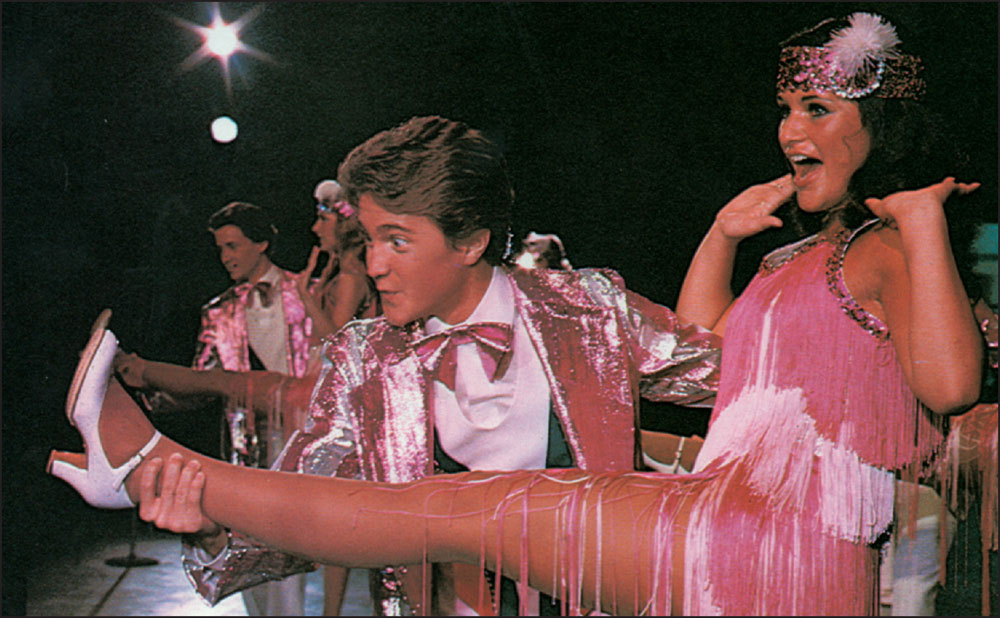

The Riverside area contained both Opryland’s original signature show as well as its signature ride. While other areas of the park were designed to highlight specific areas of American music, Riverside celebrated American music as a whole with a fabulous Broadway musical revue entitled I Hear America Singing. The show was performed across from the park’s original antique carousel, which included gondola-like ride vehicles that appeared as decorative fairyland carriages built from ornate German wood.

For many years, Opryland’s antique carousel was the centerpiece for most of the parks advertisements and promotions. Contrary to what early marketing materials claimed, the attraction was not built in the 1800s but created around 1905 by ride designer Hugo Hasse Borg und Talbahn. The ride was built from wood gathered from the Black Forest of Germany. The attraction, with its eight gondolas, first operated in Copenhagen before going into storage for nearly 50 years. Pete Logan, from Showcrafts, Inc. of Miami, found the ride for Opryland, refurbished it, and installed the attraction on its own island in the park. When Logan first found the ride in Copenhagen, it was in 5,000 unmarked pieces, weighing 50,000 pounds, with only a faded picture postcard to guide the installation.

This is how Opryland’s original carousel appeared in the early 1900s at a fairground in Europe. The term “carousel” is not quite the correct classification for the attraction. Having no horses or animals, the ride was technically defined as a “circular switchback.” A huge success in Europe, these slow-moving attractions allowed the public an opportunity to enjoy luxury that was in sharp contrast to their lives.

The details of the antique carousel were true works of art. Each of the eight gondolas were adorned with ornate women, babies, cherubs, and bats—all German good luck symbols that were hand-painted to enhance the detail of the original art. In addition, the ceiling panels of the attraction were delicate original oil paintings on canvas. (Author’s collection.)

The only production that was staged during both Opryland’s opening and closing year (though not continuously) was the park’s flagship musical I Hear America Singing. The musical journey through 100 years of American history featured a live 12-piece orchestra and an 18-member cast. The production was originally slated to be the nighttime finale to the park’s operating day. However, it was feared that the music would drift over the Cumberland River and disrupt nearby residential areas. Consequently, the park’s first indoor, air-conditioned theater was built: the American Music Theatre. The show’s song selection would vary slightly each year; however the bulk of the show would remain the same, with a few current songs added to the set list. Consequently, the running time of the show would fluctuate. A completely revamped version of the show, entitled I Hear America Singing Its Song, was staged for a single year in 1985 in the Encore Theatre (the former Showboat Theatre). The original title and themes would return to the American Music Theatre in 1995.

Paul Crabtree, original writer of I Hear America Singing, says that the show was “full of salutin’, recruitin’, and disputin’ songs. It’s music that reflects what happened to us socially and culturally through the impact of war, the miseries of depression, the jubilation of happier times, and the feelings and reactions of people to events across the years.” The show had several cast recordings and was even staged during halftime at the 1981 Orange Bowl in Miami.

The American West area of Opryland was built to be reminiscent of El Paso, Texas, in the 1880s, complete with a cantina, a blacksmith, and a general store. However, instead of desperadoes gunning each other down in the street, there were “sing-outs,” as strolling bands and the Opryland characters roamed around the area entertaining visitors with impromptu shows.

The Tin Lizzies attraction allowed one driver and up to three passengers to cruise along in a gasoline-powered 1911 Model T. The Tin Lizzie automobiles traveled at five miles per hour along a winding, overlapping, 1,200-foot roadway. A central guide rail in each lane ensured that motorists remained on the road.

The ambassadors for the park during the early years were six original larger-than-life musical instruments that roamed the grounds, especially the American West area. The costumes weighed 40 to 90 pounds each and could be up to nine feet tall. From left to right are Yancy Banjo, Johnny Guitar, Delilah Dulcimer, Barney Bass, Frankie Fiddle, and Jose Mandolin. The characters appeared on everything from coloring books to collector plates.

One of the grander shows envisioned for the park was the “American Horse Pageant,” a theatrical horse celebration about how horses were used to shape America. A large horse arena with a 1,000-seat stadium was built, and the Loretta Lynn Rodeo was recruited to perform in the show as Indians, trappers, pony soldiers, Pony Express riders, and cowboys. Unfortunately, when it rained, the arena turned into a giant mud puddle. The crowds did not seem to take to the show (and neither did the horses). During the park’s second operating year, the horses were sent home, and the arena became the Showboat Theatre.

At the La Cantina Theatre, eight young musicians/artists presented an improv review to an audience relaxing at café tables and around the stage. The opening show, entitled They Went That-A-Way, featured song, dance, comedy, and lots of give-and-take between the audience and entertainers. The venue changed names several times before becoming an arcade and, ultimately, the Opry Sound Studio, where visitors could record their own song on tape.

Also called Ryman’s Ferry, the Raft Ride allowed visitors to experience a relaxing journey aboard a four-person, battery-powered craft built to resemble a wooden flatboat of yesteryear. Eagle Lake was the staging area for this attraction, with stumps and trees dangling with moss that surrounded visitors as they passed by an old shanty boat.

The Lakeside area got its name from the three-acre body of water that dominated that territory of the park. Originally designated Lake Cumberland during the design phase, the lagoon was later called Eagle Lake once the park opened. (Author’s collection.)

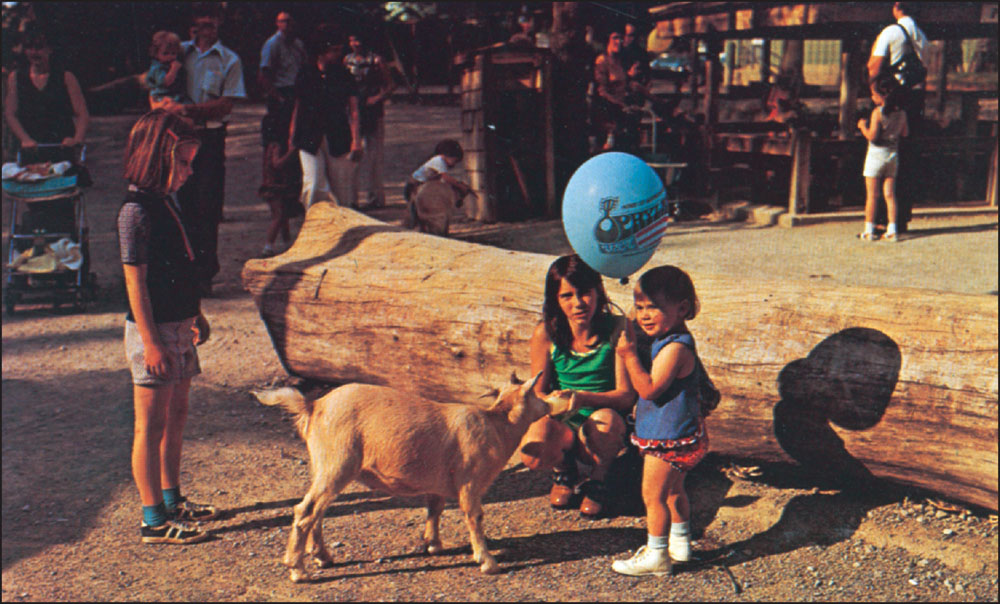

When the park first opened, there were two petting zoos. One near the American West area was set aside for farm animals, such as ducks, geese, lambs, goats, and pigs. The other animal petting attraction was near Opry Plaza and specifically for wild animals, such as deer and raccoons. Opryland animal specialists chose the park’s animals based on their gentleness.

The Music of Today, or “Mod,” area was designed to highlight the changing scene of music occurring during the 1970s. Even the architecture of the shops and restaurants had a mod flavor, with varying angles and alternating colors. Shows such as the “Opryland Rock Show” used the roofs of buildings in the area as stages, such as the canopy above the ice-cream parlor and pizza parlor.

The Music of Today section reverberated to the melodies of “Old Aunt Mary,” an antique, Belgian calliope built in 1920 that operated as if it were a 70-piece band, replicating the sounds of winds, strings, and percussion. It was programmed to play more than 100 arrangements, from the “William Tell Overture” to “Aquarius.” Unfortunately, it was destroyed during the 1975 flood that pushed the Cumberland River over its protective flood wall and into the park.

The Skyride was a cable-car ride manufactured by Von Roll and featured two stations, one in New Orleans and the other in the Music of Today area (later Do Wah Ditty City). The stations were 1,139 feet apart. Unlike similar rides at other parks, both stations were at ground level. The Skyride allowed guests to quickly travel across the park while getting an aerial view of most attractions. There were four towers to support the Skyride at approximately 220-foot intervals. There were two 85-foot main center towers in the middle of the cable route and two 65-foot towers near each station. There were a total of 40 numbered cars. Initially, red cars had even numbers, and blue cars had odd numbers. The exception was No. 40, which was painted orange. In later years, the color pattern changed, and some of the cars were randomly repainted green.

The number of cars operating on the ride was based on park attendance and determined by the area supervisor. The park’s daily attendance projection would determine if there would be either 15, 20, 25, 30, or 35 cars on the loop. There was a strict limit of four guests per car. Late in the day, as the crowds dwindled, operations would make the call to pull cars out of rotation. Mod/Do Wah Ditty City would usually pull three while New Orleans would pull two.

Opryland’s only thrill ride when it opened was the Timber Topper (later renamed Rock ‘N Roller Coaster). It was a unique roller coaster from Arrow Development that had twists and turns through the park’s trees without touching a branch. Guests might be moving toward a tree and suddenly swerve away as the ground dropped away below. The Timber Topper was the 11th tubular steel roller coaster ever constructed.

The “Animal Opry,” originally conceived as part of Opryland’s never-built Family area, was eventually constructed between the Music of Today and the American West. Later named “Animal Circus,” the production included Madam Patricia, a world-famous dancing goat; Maggie, the baby elephant; guitar picking geese; a piano-playing pig; a cow that played a cellblock harmonica; and a duck named Burt Bachaquack that played the drums.

Shows were not limited to strictly adults. Theaters were built specially for the smaller set as well. From clowns to the “Billy Boy Beagle” puppet show, there was enough entertainment for the young and the old.