TWO

Double Agents, Turncoats, and Traitors

SOMETIME AROUND 1850, ALLEN PINKERTON, A CHICAGO DEPUTY SHERIFF, established the first U.S. detective agency and named it after himself. His motto was “We Never Sleep,” and the agency used an unblinking eye as its logo—the source of the expression “private eye.” Pinkerton did some counterintelligence work for the Union during the Civil War. After the war, he explained the merits of the double agent: “In war, as in a game of chess, if you know the moves of your adversary in advance, it is then an easy matter to shape your own plans, and make your moves accordingly, and, of course always to your own decided advantage. So…I concluded that if the information intended for the rebels could first be had by us, after that, they were welcome to all the benefit they might derive from them.”

Intelligence developed by a double agent can change history. As World War II began, British intelligence services were reeling from a superb double agent operation that German intelligence had run against them. But by the end of the war, the British had developed their own version of a double agent operation—a phenomenally successful espionage caper aptly code-named the Double-Cross System. Until some new genius builds a better one, the Double-Cross System remains the ultimate double agent scheme in espionage history.

During a typical double agent operation, an agent works for an intelligence service, while secretly working against this service for an opposing service, which provides false information to the agent. Double agents are usually created by threats and inducements from one of their two masters. A double agent is a potent adversary, as British intelligence officers learned when they were caught in the German sting at the beginning of World War II.

After Britain declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain hoped to rapidly end the war by negotiations. The SD (Sicherheitsdienst, the German Security Service) decided to play to the British yearning for peace while at the same time staging a fake anti-Hitler operation that would smoke out real dissidents. A German agent working for S. Payne Best, an officer of MI6, the British Secret Intelligence Service, infiltrated a genuine opposition group and, in traditional double-agent style, acted if he were controlled by Best while secretly working for the SD.

The agent claimed to have set up meetings for best in Holland in October 1939 with a German officer who called himself “Major Schemmel” and said he was involved in an anti-Hitler plot. Accompanying Best was H. R. Stevens of MI6. Best had been empowered to tell Schemmel that Britain would accept an end to the war and grant Germany its territorial claims up to 1938 if the German army overthrew Hitler. Schemmel said that the plotters would arrest Hitler and take over Germany. But Schemmel told Best and Stevens that the leaders of the plot wanted to speak directly with British government officials.

MI6 arranged for a plane to pick up the Germans at Venlo, near the Dutch-German border. On November 8, while Best and Stevens awaited the German delegation, a car smashed through the border checkpoint, Nazi gunmen firing at the Dutch border guards. Germans leaped from the car, grabbed the two Britons, and sped back across the border into Germany. Schemmel turned out to be Walter Schellenberg, deputy leader of the SD.

The MI6 officers were handed over to the Gestapo for interrogation and were imprisoned until the end of the war. A postwar MI6 investigation revealed that they gave up enough information to enable the Gestapo to eradicate much of the MI6 network in Europe.

Winston Churchill, who replaced Chamberlain as prime minister in May 1940, sought no deals with Germany. He enthusiastically supported the work of the Double-Cross System, a scheme to make double agents of captured German agents who had slipped into Britain. The Double-Cross System gave them a stark choice: Work for us or face the consequences.

At the heart of the system was the mixture of true and false secrets that the doubled agents transmitted by radio to a completely deceived Abwehr, the German military intelligence organization. The Germans not only accepted the false intelligence but also sometimes acted on it—fulfilling the committee’s hope to “influence and perhaps change” German plans.

The idea of doubling an agent is at least as old as the spy advice Sun Tzu gave in the sixth century B.C. and as new as 21st-century warfare. General Tommy Franks, commander of U.S. military forces when the Iraq War began, revealed in 2004 that an Iraqi intelligence officer, under cover as a diplomat, asked a U.S. army officer to spy for Iraq. The American feigned agreement, thereby becoming a double agent. He gave his Iraqi handler phony documents that led Iraqi strategists to deploy forces to areas far from the real invasion route.

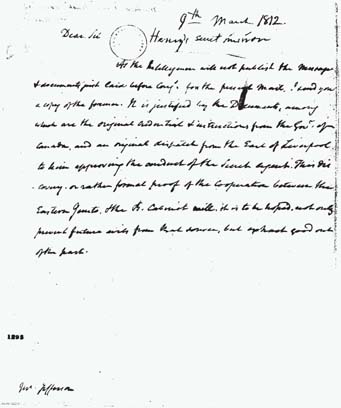

One of the “Henry letters,” which President Madison used to prove to Congress that the British had hired Capt. John Henry as a spy to foment unrest in the Union. The letters helped spark the War of 1812.