Garden Allotments

Garden Allotments

Garden Allotments

Garden Allotments

NEVER before was there such a need and, happily, such a demand for knowledge as exists now on matters of serviceable gardening by the spade workers of the community. Great results have already been achieved in much more than doubling the produce of the soil under tuition and encouragement. Not only may still greater results be confidently expected, but they are bound to be more numerous as the years roll round.

No occupation is more healthful than that of gardening, or more inspiring, when men and youths have learned to love it. They are then never so happy as when on their plots, and these never fail to respond to cultural care by the yield of bountiful crops. Men who have spare hours at disposal and opportunities for spending them on allotments cannot be more creditably, more interestingly, and more profitably engaged – i.e., when by their knowledge, love, and industry they make themselves masters in the art of soil cultivation. Many have done so to their great advantage, but still far more need sound guidance. Can it be afforded by an old soldier who has risen from the ranks of honourable labour and is more than willing to try?

Science and Practice

Science and Practice

First, then, though plain matter-of-fact routine is needed by plain and earnest workers, they also ought to know the ‘reason why’ certain operations should be performed; and, knowing this, they will proceed with greater confidence along the straightest and surest path to the object of their hopes. ‘We well know,’ wrote a wise man, ‘that science points out and illumines the path of the gardener, but the path itself is good practice.’ Along that path, and guided by that light, we will travel together for a little while.

A Good Foundation – The Soil

A Good Foundation – The Soil

When a man commences to build, his first concern is for a good foundation. So it is in gardening, and we will therefore start at the bottom and work upwards – start with the soil. What is soil? It is the pulverised matter of rocks, and varies as rocks vary. It is eventually enriched by the residue of vegetation, which grows and decays. It is this which gives to soil its dark colour, the colouring matter being known as humus, and in due proportion serves an important purpose. In excess it is injurious, yet there is a remedy – lime, which changes to chalk.

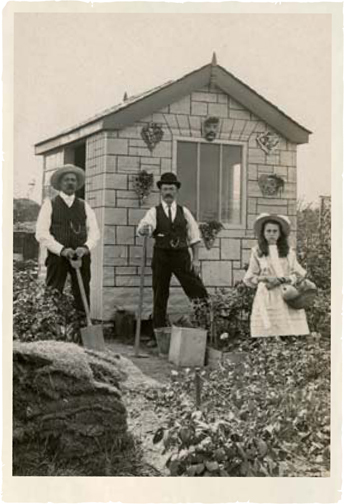

Allotment gardeners and shed, c. 1910

Soils differ extremely – one extreme being clay, which represents heaviness; the other extreme being sand, which represents porosity. Blend the two and we have loam. If the clay greatly preponderates we have strong or clayey loam; if the sand much overpowers the clay we have light or sandy soil. Provided that soils can be worked freely, smashed, and pulverised (that being important), the stronger they are the better crops they will grow.

These strong loams or soils are called ‘holding’ a good ‘holding soil’ being a common expression, and a scientifically correct one, because the food of plants is literally held in such soils for appropriation by their roots. Sand has no such power, and the food received naturally in the form of rain and atmospheric gases, or artificially in manure, slips through it. That is why sand is poor, and without the addition of clay or heavy soil cannot easily be made rich.

Digging and Trenching

Digging and Trenching

In a book published for amateurs they are told to take out a trench two feet wide and deep, then to turn into the bottom of this trench the top spit of the next two feet in breadth, and from below this to dig out a foot of the fresh subsoil and place it on the other, and so proceed till there is a foot in thickness of this bottom soil, which may have been buried for centuries, all over the piece, the best soil being then a foot under the worst. That is dangerous teaching. In an experiment £80 were spent in trenching a piece of land in that way, and then much expended in manure for making the bad soil grow something; but no good crops were had till the whole piece was trenched over again, and then the cost incurred was twice as much as the freehold was worth. There are thousands of similar examples on a smaller scale of doing what is really important work wrongly.

Using cold frames in Aberystwyth, c. 1901

The right way is to so dig or trench that only two or three inches of the raw under-soil may be mixed with the better surface soil, breaking up the subsoil and leaving it at the bottom of the trench; and if it can be covered with vegetable refuse of any kind (except deep-rooting weeds), green or decayed, the bad soil will be made better, and more of it can be turned up at the next digging. Never dig ground when it is frozen, covered with snow, nor when the surface treads into a puddle. It would be better to pay a man for resting than for working under these conditions, for digging in ice of necessity lowers the temperature of the soil, and trampling on it when wet squeezes out the air. When the work is done with the greatest ease and comfort to the workman it is done the most efficiently, and it can be done better and easier with forks than spades in heavy soil.

Light porous soils ought not to be manured and dug in the autumn, or the winter rains will wash out the nutriment, and the larder will be comparatively bare by the summer. They should be dug in early spring, and well trodden before cropping, so that the manurial matter applied may be the better retained.

Seeds and Sowing

Seeds and Sowing

Procure the best possible seeds, and sow thinly – preferably, in drills, in which small seeds should not touch each other. A weak, ill-fed seed cannot produce a robust plant; but remember that good plants cannot be had from the best of seeds by the overcrowding of the seedlings. Practically all vegetables except the onion family and asparagus produce seeds which divide into two lobes or seed leaves. These cannot be too large and strong. If they press against each other the plants are weakened in their infancy – often ruined. Seeds should be sown at a uniform depth for each kind in pulverised soil, not at different depths in cloddy soil. Small seeds are often covered too deeply; very large seeds not deeply enough, as they need more moisture than the smaller kinds. As a rule, very small seeds, such as cabbage, turnip, and others of a similar size, may be covered just under an inch deep; onion, carrot, parsnip, about an inch; radish, spinach, and beet, nearly 2 inches; peas, 3 inches; beans, 4 inches; but all are better sown deeper in summer, when the ground is dry, than in early spring, when it is moist.

Thinning Seedlings

Thinning Seedlings

Too thick sowing and too late thinning of seedlings is a double evil by far too common. It means wasting seeds and spoiling plants, besides abstracting nutriment from the soil by those drawn out too late and thrown away. All such as beet, carrots, turnips, parsnips, and others are usually thinned after crowding. Surplus plants should always be drawn out singly from time to time before they touch each other, without disturbing those which are left to become larger.

The Action of Leaves

The Action of Leaves

When the important work that is done by leaves is fully comprehended those vital parts of plants will be more cared for and cherished. With the best seed, soil, manure, and climate in the world, it is not possible for any person to obtain the greatest bulk of the best produce in the absence of sound, strong, clean, healthy leafage of whatever crops he may desire to grow. The leaves are the lungs of plants, and more. They are the breathing, food-manufacturing, and digestive organs of every plant and crop grown in gardens or allotments.

The Duty of Cultivators

The Duty of Cultivators

Success in gardening is a question of doing all things, especially small things, well, and not too late. Remember the words of a famous General: ‘I promote’ (said Napoleon) ‘those men who are careful in carrying out small details; any elephant can lift a hundredweight; few can pick up a pin.’