Two Brains: Many Possibilities

The family is one of nature’s masterpieces.

—George Santayana

AS YOU ALREADY KNOW, OUR BRAINS ARE DIVIDED into right and left hemispheres. For many animals, the two halves of the brain are essentially identical, providing redundant systems as backup in case of injury. Dolphins and many birds, for example, sleep one hemisphere at a time, allowing them to remain in constant motion and vigilant to threat.1 Primates, on the other hand, have followed an alternative evolutionary path where the hemispheres differentiate in both their structure and function. And if that isn’t complicated enough, men’s and women’s brains and hemispheres are different and follow somewhat separate developmental paths. Both lateral specialization and gender differences are important aspects of the evolution of our social brains.

The movement away from identical hemispheres was likely driven by the need for more neural territory once heads had grown as large as possible given the size limitations of the birth canal. More neural space allows for the development of new skills and abilities, increasing speed of processing and behavioral and cognitive flexibility.2 One aspect of increased hemispheric specialization has been an increase in the size of the corpus callosum, the primary communication pathway between the left and right hemispheres.3

NATURE’S ASYMMETRY

By denying scientific principles, one may maintain any paradox.

Galileo Galilei

Over a century ago, the Catholic Church chided Paul Broca for suggesting that language was lateralized to the left hemisphere, assuring him that God would not have made us asymmetrical. Nature, it appears, had other plans. In fact, the most obvious difference between the hemispheres in most of us (primarily right handers) is the dominance of the left for spoken language and the right for bodily and emotional processing. For the first 18 months of life, the right hemisphere experiences a growth spurt as we develop attachments and begin to build structures responsible for emotional regulation. Meanwhile, the development of the left hemisphere is held back, reserving space for language abilities to emerge during the second year of life.

In line with their functional specializations, the right and left hemispheres process information somewhat differently. The left is more linear and sequential (good for language and logic) while the right can simultaneously analyze multiple elements of the same phenomenon (good for visual and imaginative processes). This is why neurons in the right are more intricately connected, and neurons in the left are organized into linear pathways.4 Although the hemispheres have different specialties, they cooperate for most tasks, each contributing its own set of abilities.

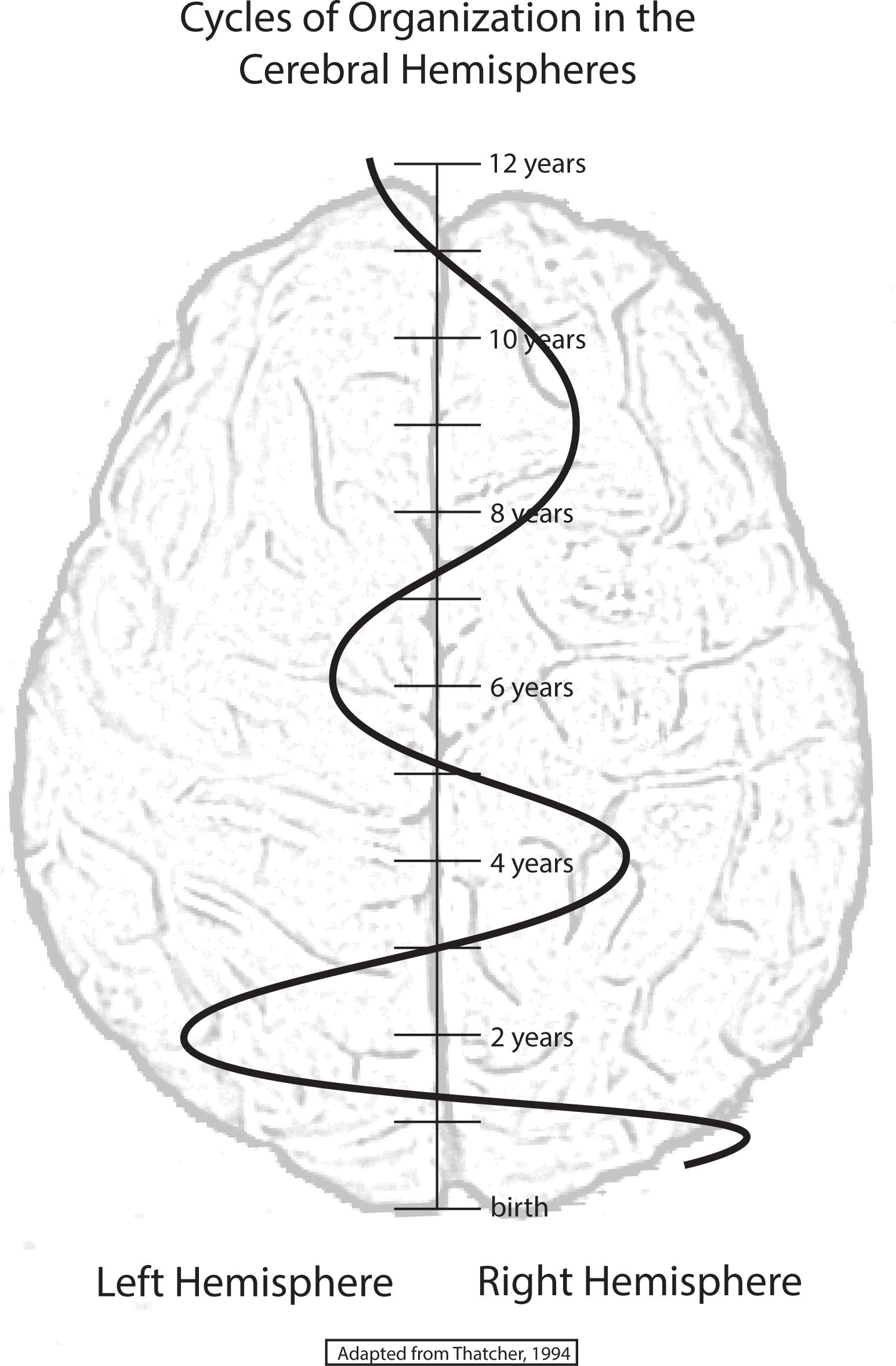

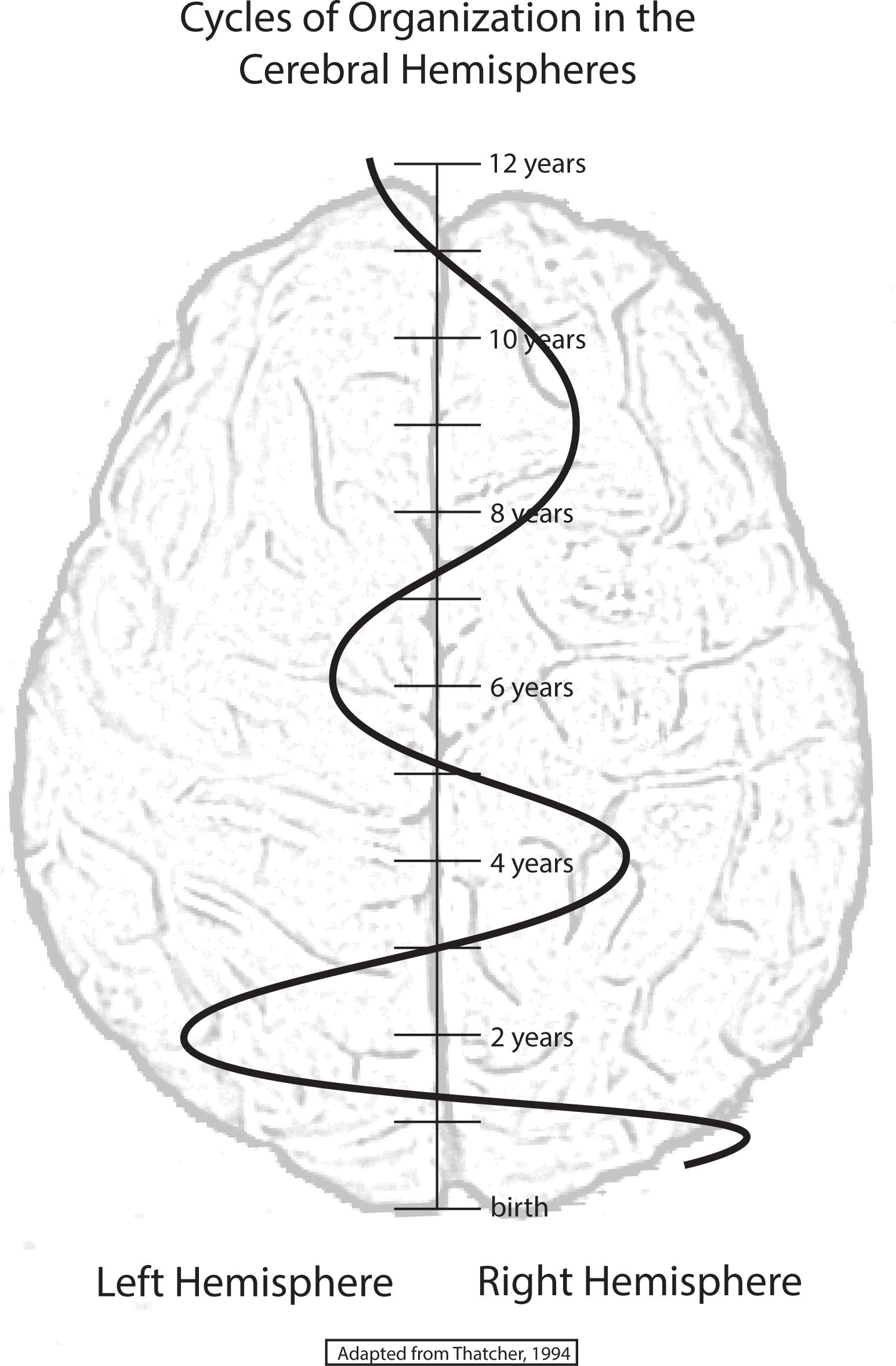

Interestingly, we are finding that throughout development, the nature and extent of the relationship between the hemispheres appears to change. During the first few years of life, the hemispheres operate in a relatively independent manner. As the connecting fibers between them mature, coordination and integration increase. As we move into adolescence and young adulthood, there is considerable hemispheric specialization in many memory and spatial functions.5

Beyond young adulthood, there appears to be a reduction of hemispheric asymmetry in the prefrontal lobes for tasks of memory and sensory processing. These shifts result in a processing strategy that can be just as accurate, but slower and more effortful. As the brain continues to mature, changing activation patterns across regions of each hemisphere reflect complex adjustments in how we process information.6

ONGOING ADAPTATION

Little knowledge is not to be compared with great knowledge, nor a short life with a long life.

Chuang Tsu

Despite neuroscience’s historic pessimism about the aging brain, the rest of us have noticed that age corresponds with an increasing fund of knowledge, a deeper comprehension of meaning, and a preservation or even improvement of narrative abilities.7 Healthy older adults actually demonstrate a greater complexity of brain wave patterns reflecting the increased distribution and coordination of cortical activation.8 Interestingly, high-performing older adults show bilateral activation, while lower-performing older adults use the same lateralized strategies as younger adults.9 These findings suggest that as we age, a greater number of better-organized networks are participating in abstract reasoning and problem solving.

For most of human history, the lives of children, parents, and grandchildren were unchanging. Older adults had little new to learn but much to teach. And prior to the relatively new invention of written language, older individuals were the vessels of knowledge, history, and culture. Assuming a stable environment, frontal systems involved in new learning were less vital, and a holistic understanding of situations was far more important than speed. Thus, the way the brain ages appears to have been shaped by the needs of the group within an oral culture.10 Holding multiple perspectives in mind requires widespread neural participation that accesses thinking, feeling, past learning, and present realities.

This brings up an important question—could what is usually interpreted as compensation for declining function provide older adults with the kind of neural network integration that contributes to the attainment of wisdom? As we will see in later chapters, definitions of wisdom all seem to include a blending of intellect, emotional sensitivity, empathy, and practical knowledge. Bilateral participation supports the advanced social abilities traditionally sought out in tribal elders. This stands in contrast to those we think of as “intelligent” but lack the ability to connect with and understand the feelings and needs of others.

Increased neural participation may take more time but also provides us with more and better-quality information on which to base our decisions. It is not surprising that taking more time before responding to questions is usually experienced by others as the gift of reflection and thought. Wisdom emerges from deep thought, the inclusion of multiple perspectives, and concern for those with whom it is shared. While there is no argument that age-related declines in memory and processing speed do exist, older adults may be well served by taking more time to consider the multiple aspects of a problem.

OF MEN AND WOMEN

Women who seek to be equal to men lack ambition.

Albert Einstein

Just as natural selection has shaped the right and left hemispheres to play specialized and complementary roles in neural processing, males and females have also been shaped for complementary contributions to the social economy. Their bodies, brains, and biochemistries have been tuned to meet the demands of gender-specific roles.11 Sociologists often describe men as instrumental and women as expressive. Instrumental men focus on the outside world, solve problems, and attain goals related to hunting, fighting, or competing in the rat race. Expressive women stay closer to home, tending to hearth and hearts.12

In some cultures, these roles are shifting and gender roles and identification are coming to be seen as existing on a spectrum, but for most of the world and through much of our evolutionary histories, these general tendencies have bred true. Keep in mind that our brains are essentially Paleolithic, meaning they haven’t changed much in tens of thousands of years, while culture can transform in a few generations.

Differences between males and females in cognitive and emotional processing emerge early in life and persist into adulthood. Genetic inheritance, hormonal differences, and cultural biases result in male and female brains that are quite different. From the moment of conception, our bodies and brains begin to differentiate based on the presence of an X or Y chromosome. These differences set off a cascade of reactions that guide our behaviors, determine our life histories, and shape our brains. It has been said that females are the norm and males are the genetic experiment, implying that males are a modification of the basic female model. Males do seem to be more fragile, suffering higher rates of spontaneous abortion, retardation, and learning disabilities as well as more age-related indications of neural degeneration.13

When it comes to spoken language, the brains of men and women are organized a bit differently. Women have a greater density of neurons in the planum temporale, a region of the temporal lobes specializing in language.14 When given a spatial memory task, women use more verbal strategies and show greater activation in their left hippocampus, which supports language functions. Men, on the other hand, process visual-spatial information more directly without the mediation of language.15 Gender differences in the way we process information parallel differences in gray matter density, blood flow, metabolism, and patterns of neural activation.16

There are also gender differences in the fibers connecting the hemispheres. The corpus callosum and two smaller structures linking left and right hemispheres are significantly larger in women.17 In males, the corpus callosum increases in size until age 20 and then begins to decline, while in females it continues to grow until midlife.18 Females also have a higher ratio of gray matter in the corpus callosum, suggestive of more integrated processing.19 All of these differences between the brains of men and women point to what we all know—men and women experience the world and express themselves in different ways.

What specific skills and processing abilities support success in traditional gender roles? Men are better at hand-eye coordination and hitting targets with thrown objects, while women are superior in abilities related to foraging, verbal communication, and emotional attunement. Men tend to excel at tasks of mathematical reasoning and navigation over large distances, while women are better at tasks requiring semantic memory, language, mathematical calculations, and precise manual dexterity. All of these differences are likely embedded within gender role differentiation from our long history as hunter-gatherers.20

The fight-flight reaction, an essentially male survival strategy, mobilizes the brain and body to exert physical energy for combat or evasion. Increases in respiration and energy availability and enhanced sensory processing occur in the service of actively confronting danger. Given that women are generally smaller and slower than men and tend to have their young in tow, a fight-flight strategy is often not wise. Women have traditionally survived less through strength than by forming affiliations in a “tend and befriend” strategy.21 For humans and other mammals, females with more social skills and larger social networks have a higher likelihood of survival for themselves and their children.22

SEX HORMONES

It’s a funny thing that when a man hasn’t anything on earth to worry about, he goes off and gets married.

Robert Frost

Estrogen and testosterone are sex hormones that shape brain growth and contribute to determining the cognitive strengths of each gender for specific reproductive and social roles.23 Although much of our understanding of estrogen and testosterone is based on animal studies, the increasing medical use of hormone supplementation is expanding our knowledge of how they function in humans, especially their impact on the brain. Let’s begin with estrogen.

Estrogen receptors have been discovered in diverse regions of the brain, where it both enhances learning and serves a protective purpose in injury and aging.24 It protects neurons from cell death and supports myelin formation and maintenance.25 Estrogen increases neurochemical activity in the synapses and results in greater branching of neurons supportive of new learning and works against oxidative processes that damage neurons over time. Given the strong link between estrogen, brain health, and neural longevity, estrogen is obviously more than a sex hormone.26

The connection between estrogen and the hippocampus is an ancient one, and the hippocampus still responds robustly to estrogen.27 Surges of estrogen triggered by childbearing turbocharge the hippocampus to support the spatial learning and memory required for finding, storing, and retrieving food. In fact, as estrogen levels rise and fall during the phases of the menstrual cycle, so do women’s motor and perceptual skills.28 A single administration of testosterone has been shown to enhance visuospatial abilities in young women, while testosterone replacement therapy in men of any age improves muscle strength, sexual functioning, mood, and brain functioning.29 In a 10-year study of over 400 men, higher levels of testosterone were positively correlated with better memory, visual-motor functioning, and an overall reduced rate of decline and the development of Alzheimer’s disease.30

“NOW SHE WANTS ME TO DO THE DISHES”

Men are taught to apologize for their weaknesses, women for their strengths.

Lois Wyse

During early and middle adulthood, gender roles related to reproduction, child care, and basic survival are front and center. But as men age, the demand for them to be protectors, hunters, and warriors gradually declines. In healthy aging, flexibility in social roles increases—men may assume the role of diplomat, peacekeeper, or nurturer, while women become more likely to engage in activities outside of the home and take on leadership roles. In other words, later in life, each gender can take on more of the aspects usually associated with the opposite sex.

The emotional adjustments necessary for retirement often catch men by surprise. Some adhere so rigidly to the role of the stoic breadwinner that they find themselves completely lost when it comes to relaxation or trying something new. Making it more difficult is the fact that men are often socialized to believe that roles within the family and community are demeaning, less serious, and less important than their past careers. Relentlessly driving themselves for decades, they have never given a thought to what their first morning of retirement will be like. And while some replace careers with hobbies without skipping a beat and others discover they enjoy relaxing, still others spin out of control. These changes present new challenges and new opportunities.

For this last group of men, retirement is a series of shocks. Nothing feels right; they become disoriented and confused, and mourn their lost identity. Norm was one such fellow. He proudly described himself as having a “double Type A” personality: A legal shark whose prime directive was to swim forward and find money. For the four decades between receiving his Yale law degree and retirement from the firm he cofounded, Norm averaged 60-hour weeks and couldn’t recall a sick day. After considerable coaxing and multiple postponements, he would begrudgingly go on vacations with his family, but always with a briefcase full of work. As technology improved, he proudly told me he was able to get as much done on safari in Kenya as he did at his Los Angeles office. “I’m bad, aren’t I?” he asked with feigned shame and a wry smile. By working on vacation, he felt that he had eluded his wife’s attempts to control him.

Going into retirement cold turkey caught him by surprise. He had earned it but had no idea what to do with it. His career had left no time for hobbies, sports, or friends, so there was nothing and no one waiting in the wings. He spent his first weeks of retirement drinking lunch and sleeping through the afternoon. This pattern left him sleepless most nights, alone with his thoughts, and not liking his own company. He began to realize that he didn’t know his children and that they had grown up and established their lives in other cities without him. All his friends were at the firm, still working his old schedule and never available to get together. When he visited the office, everyone was glad to see him—as they passed him in the hall running to their next meeting. He became envious of his former colleagues and began to strategize about how to “unretire.”

Norm was referred for psychotherapy by his internist, who had given him medication for insomnia and depression. He avoided calling me for months, until the day his wife asked him to do the dishes. When Norm found himself standing at the sink crying, he decided to give me a call. A week later, Norm sat across from me and asked, “What is happening to me? I don’t understand why I’m such a mess.” It was obvious that he was a man accustomed to getting down to business. His sentences shot out in rapid succession. “It must relate to leaving the firm because I was fine until I stopped working. I lie awake at night thinking of excuses to go back to work. I’ve even thought about moving to another city and starting a new firm. The crazy thing is, I have more money than I could ever spend and I’ve got a wonderful family—we’re even expecting our first grandchild in a couple of months. What is happening to me?” The more he spoke, the more desperate he seemed to become. His state of mind was contagious, and I could feel myself getting increasingly agitated.

As I took in his experience, he continued, “My wife asked me to do the dishes, and it made me cry. Can you believe it—a grown man washing dishes and crying like a baby? What am I crying about? Everything is fine—we’re healthy, we live in a huge house, we have good neighbors, complete freedom, we can buy anything we want, do anything we want to do—we have all the time in the world. Why do I feel like I’m going to jump out of my skin?” Norm looked me straight in the eye, pointed his two index fingers at me, and said, “Okay. GO!” Caught up in Norm’s exploding emotions, I had forgotten about having to respond.

It appeared obvious that Norm’s brain had been shaped to separate his conscious awareness and his inner experience. His ability to suppress his feelings had served him well in surviving a difficult childhood, serving in the military, and fighting the daily battle of courtroom litigation. I imagined that neural networks dedicated to thinking and feeling biased toward the left and right hemispheres had developed with insufficient cross talk and functional integration. His brain appeared to have been shaped in this fashion through a combination of temperament and experience. The challenge now was to resculpt it in a way that would allow him to adapt to new challenges.

Although Norm’s image of himself was that of a fearless soldier, it was painfully obvious that he was ill equipped for life during peacetime. I knew that he was not ready to deal with his feelings directly. He needed a way of thinking about what was happening that would allow him to approach his internal world slowly while maintaining his pride. Norm needed a new story about himself and the meaning of his life, and a plan to guide him into the future. So instead of responding directly to his command, I began by telling him a story.

“While you were talking, I was reminded of a veteran I worked with some years ago. He went to Vietnam in his early 20s and did three tours of duty before coming home. He was highly decorated, loved the men in his platoon, and would have signed up for a fourth tour if the war hadn’t ended. He came to therapy 15 years after the war because he was still having a hell of a time adjusting to being home. He had a great wife and two children he adored, but he was always anxious and afraid. He stayed up most nights and walked the perimeter of his property like he was on guard duty. Planes and helicopters going overhead or cars backfiring would have him diving for cover. What we’ve learned over the past decades is that brains adapt to crisis and often need help readjusting after the crisis has past. So while you and I know that this situation isn’t a matter of life and death, the primitive parts of your brain may not understand the difference.”

Norm identified with this experience, as it seemed to capture his imagination. He had no problem seeing himself as a combat veteran who needed to adjust to civilian life. He shared some recent experiences of being startled out of sleep in a cold sweat because he had dreamed that he missed a filing deadline or went into court unprepared for an important case. These discussions slowly led us to explore the typical architecture of the male brain, its biases, and the adaptational challenges men face in middle and later adulthood.

Always up for a challenge, once Norm had a map of the territory, he engaged in therapy with his usual focus and energy. I constantly encouraged him to be aware of how he was feeling along the way and mindful of the choices he was making throughout the day. This wasn’t easy for him, and I had to find many ways to help him be more aware of his body, discover sensations, and attach them to conscious emotions. But by the time his first grandchild arrived, he had taken the first steps on the long path to becoming a more centered and emotionally available elder, preparing him to contribute to his family in a new way.