We are so thoroughly trained to follow our thoughts that our mindfulness is weak.

SO FAR WE HAVE SEEN THAT THE ATTAINMENT OF wisdom requires an ongoing integration of worldly experience, emotional maturation, self-awareness, and compassion.1 This can be quite a challenge in the face of evolution’s other mandate to do unto others before they do unto us. Wisdom and compassion sometimes requires a transcendence of personal well-being.

It is not a coincidence that throughout the world, wisdom is thought to go hand in hand with time spent in meditation, spiritual retreats, and religious pilgrimages. Time spent apart from the moment-to-moment struggle for survival frees one to turn inward and explore the mechanisms of mind and emotion. The more familiar we become with the ways in which a human brain functions—its brilliant achievements and profound shortcomings—the more likely we will be able to use our minds for higher purposes.

Older people have a number of advantages when it comes to becoming wise. Their slower pace, broader perspective, and years of experience allow them to bring more information and perspective to any situation. Decreases in the distorting effects of fear and anxiety allow older individuals to see social situations with less defensiveness and more clarity. Because healthy maturing brains are characterized by widespread neural activation, they are better equipped to integrate emotion, intellect, and intuition.2 Let’s look at some of the ways in which healthy aging favors the emergence of wisdom.

SPEED VERSUS FLEXIBILITY

Age considers; youth ventures.

Rabindranath Tagore

One of the principles governing the evolution of complex neural systems is an optimal balance between response speed and response flexibility. Response speed is the time it takes us to successfully respond to a situation. Response flexibility is the number of appropriate options we are able to remember, consider, and choose from. Acting quickly requires a minimum of neural processing, while response flexibility requires slower analysis of more information and the use of more extensive brain regions. These two tendencies reflect the poles of our existence: On the one extreme, the most primitive reflexes of our brains’ evolutionary past, and on the other, what it is able to accomplish with the trillions of newer neural connections.

Think about how quickly we pull our hand away from a hot stove or how we startle when touched from behind when we think we are alone. These rapid reactions have been hardwired through eons of natural selection. They occur so quickly that we can only consciously experience them in retrospect. An urban legend circulates through the greasy spoons of New York about a cook who saved his money for years to buy a very special watch. He polished it religiously each day and showed it off to everyone he met. One day as he was taking off his watch in his work kitchen, he accidentally dropped it into the fryer—reflexively, he reached into the boiling oil to retrieve it. This was not something he decided to do, but something he found was a bad idea only after realizing what he had done.

In fact, simple responses, such as the knee-jerk reflex that occurs when the doctor hits our knee with a rubber hammer, don’t even reach our brains. They utilize a reflex arc involving the spinal cord. Basic fear responses don’t require cortical involvement but are mediated via primitive subcortical structures (including the amygdala) to get our bodies immediately mobilized for fight or flight. The braking of a car during a panic stop is another good example, something that would simply take too long to process in the cortex.

If response speed is one side of the equation, the other side is the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional flexibility that comes from assessing a situation, thinking through alternatives, and selecting what we feel to be the best option. During early development, we see a gradually increasing ability to inhibit impulses and bring past learning to bear during decision-making. As neural systems mature and integrate, they demonstrate increasingly sophisticated processing for more complex tasks. All of this occurs while simultaneously retaining the automatic reflexes that allow us to react to immediate threats.

As a rule of thumb, the more complex the analysis we engage in, the more widespread the neural participation and the more time it takes to respond. For example, when subjects are asked to make moral judgments in social situations, a wide array of cortical and subcortical regions become activated. Tasks requiring self-awareness, self-reflection, and empathy for others, recruit the involvement of broad social and cognitive neural networks.3 The complex human problems that are the focus of wisdom call upon all of these networks in both cortical hemispheres as well as subcortical structures.

Subcortical activation reflects the involvement of networks that organize primitive drives and emotions, as we attune to and resonate with the participants caught up in whatever dilemma we are evaluating. Networks of the social brain become activated when we put ourselves in someone else’s shoes. Finally, the prefrontal cortex contributes to our ability to process complex social interactions and weigh potential outcomes. This wisdom is not an abandonment of primitive emotions, but an integration of deep emotions that help us empathize with others and employ a broader perspective.

Attention to internal feelings also adds valuable information for making social judgments. Younger people, fixed on external information and environmental contingencies, are less slowed by these mediating factors that are taken into account by wise elders. In a study comparing young and old subjects on a variety of tasks, the older adults (age 60–80), while slower, performed as well or better, especially on tasks requiring social judgment.4 Older subjects have also been found to be better at recalling their feelings about real and imagined events than younger subjects.5

To act wisely, we have to simultaneously be aware of our own biases, inhibit impulses that would make us act rashly, and be empathic and caring toward others, all the while applying our intellectual abilities to complex situations. In older age we can expect a reduction of processing speed accompanied by an improvement in the pragmatics of social problem solving.6 Brain processing strategies that make for quick decisions earlier in life seem to gradually give way to the more inclusive and fine-tuned cerebral networks required for wisdom.7

A senior pilot once told me that while younger pilots react more quickly to emergency situations, more experienced pilots tend to avoid them in the first place. This seems to be backed up by research with air traffic controllers. Although reaction time and memory are superior in 30-year-old air traffic controllers, those in their 60s do as well or better in simulated emergency situations.

The combination of years of experience and changes in the brain results in the enhancement of complex skills over time. The emotional activation in high-pressure, high-stakes situations may also impair the cognitive functioning of younger pilots and controllers more than it does those with more experience and a tame amygdala. Listen to the tone of Captain Sullenberger’s voice on the cockpit recorder after he was told to return to the airport, when he said, “We aren’t going to make it; I’m putting her down on the Hudson.”

BLAME VERSUS RESPONSIBILITY

A man can fail many times, but he isn’t a failure until he begins to blame someone else.

John Burroughs

Through natural selection, our social brains evolved to quickly predict and react to the anticipated activities of others. Research in social neuroscience has demonstrated that we have a variety of neural systems dedicated to unconsciously monitoring the behavior of others that use body posture, gaze direction, facial expressions, and pupil dilation to predict behavior. These “mind-reading” systems are reflexive and fast, processing data far more quickly than the half second it takes for us to become consciously aware of what we are experiencing. They automatically generate an implicit theory of another’s motivations, intentions, and likely behaviors. This theory of someone’s state of mind provides us with both an early warning system for potential danger and a mechanism of interpersonal attunement and understanding.

While this kind of mind reading is automatic and instantaneous, we have no analogous system dedicated to self-awareness. In fact, some have proposed that self-awareness may be a disadvantage to survival because it slows down our reaction time and makes it more difficult to deceive ourselves and others. For example, if we are able to convince ourselves that we are innocent of a crime, we may be better able to fool others (and a lie detector) with our pleas of innocence. Using mind reading for deceptive purposes and personal gain is clearly demonstrated while playing poker, where the most consistent winners are those who are best at reading their opponents’ “tells” while concealing their reactions behind a “poker face.”

Many forms of self-deception appear to be baked into the human genome. For example, when others make a mistake, we tend to think that there is something wrong with their abilities, intelligence, or character. If, on the other hand, we make the same mistake, we tend to blame environmental factors—wind direction, fatigue, or the blunders of others that set us up to fail. This perceptual distortion, called the fundamental attribution error, shows that we are innately biased toward externalizing blame and looking to factors outside of ourselves for our own failures. A related phenomenon is what Freud called projection, a tendency to see our own faults in those around us while feeling free of blame ourselves. While attribution errors and projection are reflexive and serve to lessen anxiety and self-doubt, awareness of our own shortcomings requires effort and a willingness to tolerate negative feelings about ourselves.

All of us can spend hours describing the behaviors, motivations, and problems of other people and remain oblivious to the fact that we are actually describing ourselves. Couples are often completely convinced that the problems in the marriage are totally attributable to their spouses. I can relate to these states of mind because I often find myself doing the same thing. But blaming others is more than a character weakness; it is likely a natural consequence of the automatic mind-reading circuitry bequeathed to us from our evolutionary history. We automatically assess others but have no automatic process for assessing ourselves. This comes with the discipline and practice of self-reflection that is required if one is to become a truly wise person. In fact, wise individuals are mindful of these innate tendencies and learn to use their judgments of others as windows to the hidden corners of their own inner worlds.

Unfortunately, self-awareness, personal responsibility, and common sense are not that common—just watch the news or read a newspaper. The evolution of consciousness requires remembering who we are, deepening our appreciation of our interconnectedness, and learning how to listen and love rather than talk and blame. Placing our individual views in a social perspective, knowing our prejudices, and appreciating the importance of human relationships take dedication and effort. This kind of self-awareness, along with wisdom and compassion, may soon become a requirement for our continued survival as a species. As the world grows smaller, it is clear that we will need to evolve to a higher level of social consciousness.

REFLEX VERSUS REFLECTION

The art of being wise is the art of knowing what to overlook.

William James

Our brains have evolved to look outward and be on alert. When we are safe, our aggression may get channeled into exercise and sports; when food is readily available, our primitive drives to forage get converted into hobbies and home improvement projects. When reflexes and primitive drives get caught in the “on” position, we can develop all kinds of compulsive behaviors. Many of us spend time preoccupied with to-do lists or caught up in a never-ending chain of thoughts that keeps our minds spinning.

Jon had been my client for years and complained about having too many things to do. We examined his schedule, talked about cutting back on work and social obligations, and created lists of priorities from which he was to trim off the bottom third. Despite countless discussions and repeated repentance, Jon continued to be extremely overcommitted. It eventually became clear that he had made coming to therapy another thing on his to-do list. Instead of using it to make his life better, Jon had unknowingly turned therapy into part of his problem.

In the process of exploring what kept Jon going so fast and furious, all roads led to anxiety and fear. He was afraid that if he didn’t work every bit of available overtime, he would run out of money. If he didn’t keep everything under control, “all hell would break loose.” If he didn’t do everything his friends asked him to do, he would end up unloved and alone. Despite seeing the irrationality of his behaviors, nothing changed. Jon was just too frightened to even experiment with slowing down.

Meanwhile, Jon’s son was acting out in school, and his daughter was showing signs of depression. Jon’s wife described herself as a single parent, and his children’s therapist suggested that it might help if Jon spent more time with his family. Jon understood that his anxiety-driven behavior was damaging to him and his entire family, yet nothing I said—nothing anyone said—seemed to have an impact on his behavior. Just when I was beginning to think the situation might be hopeless, Jon came into a session with a big smile and the following story:

Last Wednesday morning, I was trimming my toenails before getting dressed. I got through the first nine and was about to start cutting the tenth when the phone rang. It was a call from work, and I had to go to my desk to jot down some notes. I was running late, so I put on my socks and shoes and ran out the door without cutting the last toenail. For days I was aware of that toenail, feeling it snag on my sock when I got dressed in the morning, scratching the sheets at night before I passed out. Then I forgot about it. As I was driving here this morning I realized that a week had gone by and I still hadn’t cut it. It was so long now that I could push it against the inside of my shoe. Suddenly it hit me—my wife and kids, even my own health are all tenth toenails. There’s something about this toenail that made me realize I must be crazy. I think I’m ready to start therapy.

Jon’s story highlights many important issues. The first is that compulsivity is self-reinforcing because it reduces anxiety. In Jon’s case, his anxieties about his own worth were relieved by constantly doing for others. Anxiety is the enemy of behavioral flexibility, neural plasticity, and self-insight. When we feel anxious or afraid, we focus on acting on the environment, forgetting who we are and what is important to us. Because he felt that his wife and kids were already his, they required little of the fear-driven attention he showed others. For years this psychological dynamic remained invisible to Jon. It took the metaphor of an uncut toenail and his sense of humor to break the spell. Jon was lucky. For most people, it takes a life-threatening illness, a trip to the emergency room with a panic attack, or the loss of a loved one to wake up from the spell of compulsivity.

Getting to know ourselves involves turning attention away from the demands, expectations, and details of the external world, and turning inward. While behavior is more widely studied because it is readily observable and easily measured, our inner experience is just as important. Traditionally avoided by researchers, the subjective aspects of human experience are now receiving increasing attention as emotion, empathy, and the effects of meditation on the brain have become areas of interest for research and the popular press.

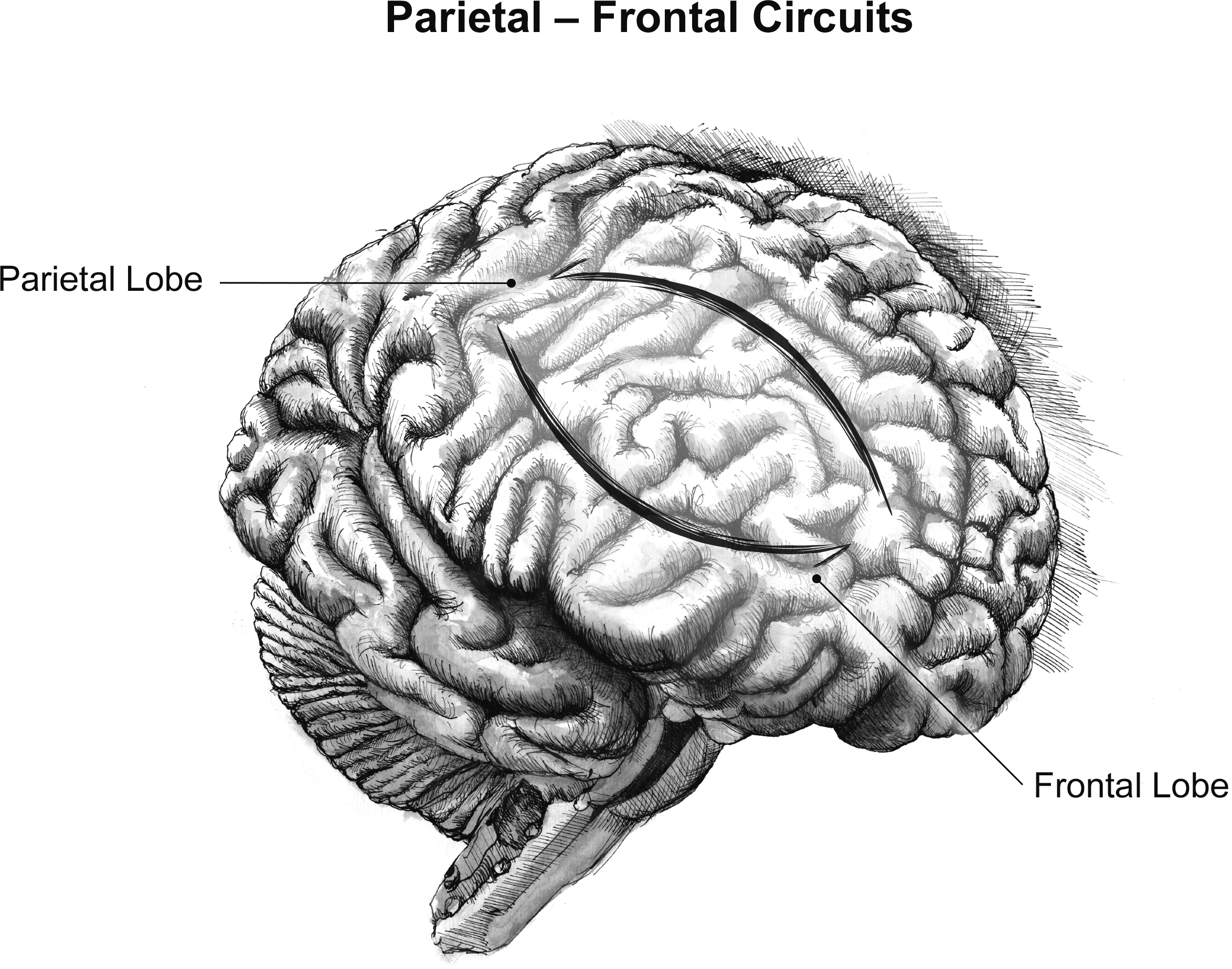

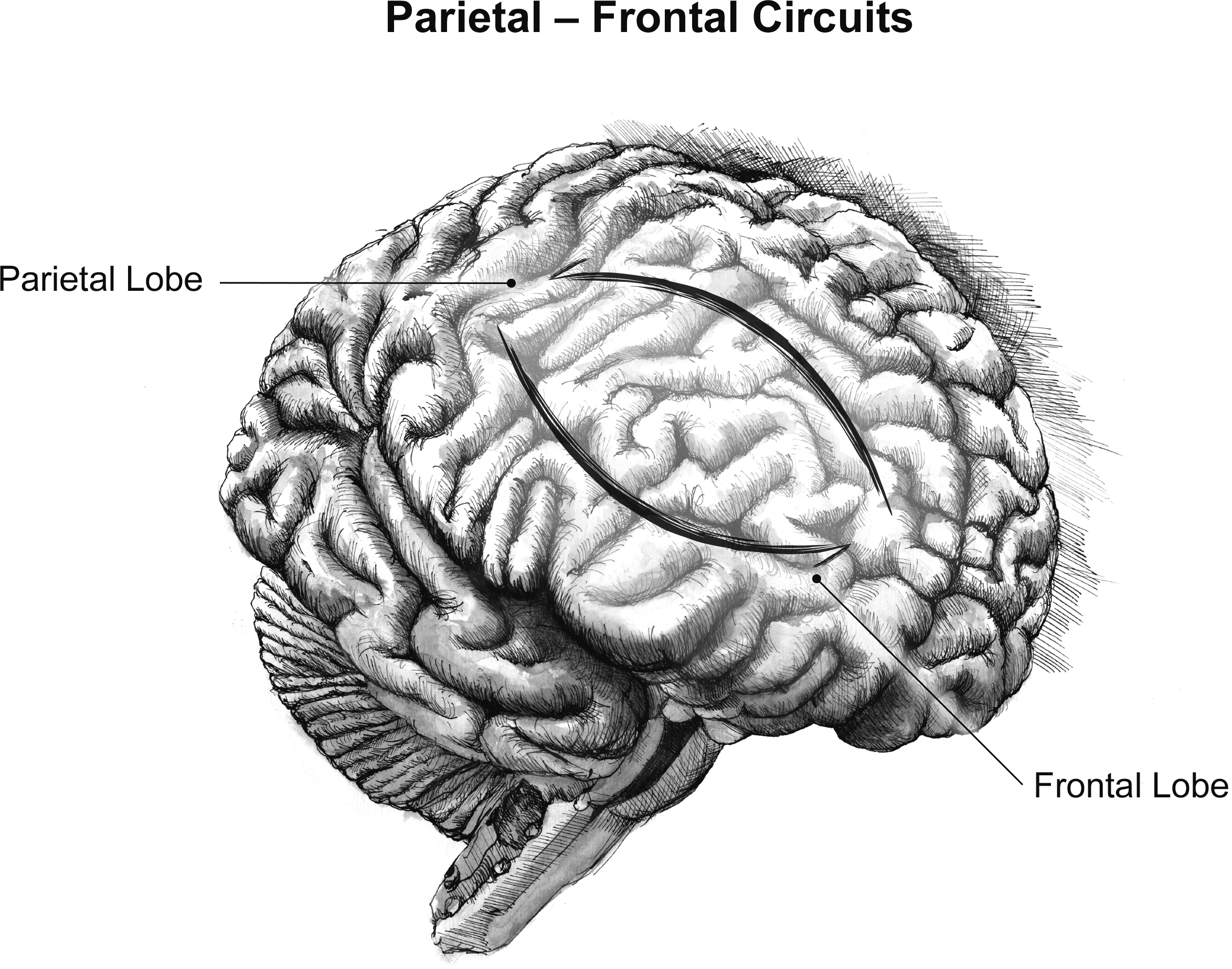

It is important to keep in mind that the frontal and parietal lobes initially evolved to allow us to navigate in space and across time. This frontal-parietal system has more recently given us the ability to navigate an internal world of imagination.8 This inner space can serve as a safe, reflective context in which to detach from the demands of the outer world in order to self-reflect and engage in deep consideration.

A quiet and safe internal world, once created, can be revisited, providing a context for private thought separate from external problem solving. These quiet moments serve as the grounds for imagination and creativity and are especially important for children in the process of forming an experience of self.9 One’s conscious sense of self consolidates during times of still reflection and creates the possibility for greater empathy for others and ourselves.

The parietal lobes, located above our ears, are at the crossroads of the neural networks responsible for vision, and hearing. They serve as a high-level association area for the integration and coordination of our senses and connect them with conscious thought.10 During periods of contemplation and quiescence, there is a shift from frontal to parietal activation.11 In fact, the same shift occurs when experienced meditators engage in meditation.12

Research has shown that greater amounts of gray matter in the temporal, parietal, and frontal lobes later in life are related to things like mature creativity, openness to divergent feelings and thoughts, and a sense of connectedness with others and the world.13 In fact, the middle regions of the parietal lobes appear to be a hub of self-representation, memory of ourselves in the world, and reflective self-awareness.14

The fact that most professionals don’t think of the parietal lobes as a component of the executive brain may reflect a cultural bias of equating individuals with their external behavior rather than their inner emotional experiences. Interestingly, studies of skulls reflecting different stages of primate evolution suggest that expansion of the parietal lobes is more characteristic of the human brain than expansion of the frontal lobes.15 We have seen that as we age there appears to be greater neural loss in frontal than parietal regions. Could the neural loss we see with age somehow support the development of enhanced mindfulness?

Narcissism in its many forms can be understood as a failure to create a secure inner world. Instead they have to rely on external validation for a sense of emotional regulation and well-being. In many ways, narcissism is the opposite of both intellectual and emotional wisdom.

THE NARCISSIST AT MIDLIFE

Success is a lousy teacher. It seduces smart people into thinking they can’t lose.

Bill Gates

Whereas the child has to deal with individuation and the adolescent with interdependence, older adults must make peace with mortality. As we wrinkle and lose some of our energy, people with identities based on beauty and physical prowess are faced with having to discover new ways of valuing themselves. You have to jump off of your body and onto your spirit for the last act of life’s journey. In other words, if we only think of ourselves as our bodies, our vitality and sense of self will decline along with our physical self. But if we can build a deeper relationship with our inner experience, the slowing down of the body can be reduced to an inconvenience.

For those whose personal identity and relationships are based on their powers of attraction, aging strikes a severe blow. A 45-year-old former fashion model once told me flatly, “You know I couldn’t have survived middle age without all this therapy!” Another fragile narcissist who suffered early trauma stated, “My makeup is a core part of who I am.” For the narcissist, aging represents a series of shaming experiences that can lead to deforming plastic surgeries, immersion in fantasies of youth, or withdrawal into depressive isolation. For these people, aging is experienced as a personal failure.

SELF-PARENTING

There is nothing like a dream to create the future.

Victor Hugo

Paul was in his early 50s when he came to therapy struggling with a self-proclaimed midlife crisis. He had worked hard, achieving success as an investment banker. Paul enjoyed the complex puzzle presented by each new company. He had to learn the business, identify problems, and find ways of increasing profitability. He especially enjoyed discovering the true financial situation of a business hidden beneath layers of creative bookkeeping. Driven by what he called perfectionism, he worked day and night, driving himself, his partners, and employees with what he described as relentless dissatisfaction.

Dissatisfaction, that’s it! I’m dissatisfied with everything—myself, my colleagues, my living situation, and the women I meet. I’m never happy with anything I do in any area of my life. I was dissatisfied with being married and now I’m dissatisfied with being single. I’m dissatisfied with where I’ve gotten in my career, and can’t believe how most of the guys who I’ve hired, trained, and helped get established have surpassed me. They’ve all gone on to bigger things, are more respected, and make a lot more money. I’ve been passed over for promotions, been let go during downsizing, and gone from job to job trying to find the right place to use my talents. My life is half over and, so far, it feels like a bad dream that just won’t stop.

Paul survived a tumultuous childhood full of pain and conflict. His mother had abused drugs, both parents were physically violent, and his father abandoned the family when Paul was 13. It became clear to Paul that his mother was unable to care for him and his younger sister, so he took it upon himself to enroll both of them in boarding school. From as early as he could remember, he kept long hours, played and worked hard, and assumed he was destined for great things. For 25 years, his superstar identity distracted him from his emptiness and emotional pain, but turning 50 burst his bubble.

In my mind, I’m still the young stud that was going to set the world on fire, marry a supermodel, and live in a mansion. Instead, I’m living alone in an apartment, dating women I don’t respect, and struggling to pay my bills. How could I miss the reality of my life for so long? I’ve always lived in the fantasy of being the top dog and suddenly, it’s as if I went from superstar to loser overnight. My reality sucks! Since I realized how depressed I was, I’ve tried to outrun it by getting up earlier, doing more deals, and working out harder, but the truth keeps catching up with me.

As a child, Paul had no guidance in how to forge an identity, get a realistic sense of his own capabilities, or learn how to cope with difficult emotions. His early narcissism, the narcissism we all share as young children, never matured into a healthy and balanced sense of self-esteem. He remained in a world of black-and-white thinking, where human value was measured against perfectionistic ideals. As a result, he was disappointed with everything and everyone, especially himself. Paul shrugged his shoulders.

I feel like a stranger in my own life. All of a sudden I find myself at 50 with the wrong set of rules. Most of the time I’m confused about what to do and it stops me in my tracks. I still have the impulse to work hard, chase women, push myself to the limit, and try to achieve the goals that have always been before me. The difference is that I can’t seem to shake the feeling that it’s all meaningless.

Despite being put off by aspects of his narcissism, I felt that Paul was a remarkable man. From a hellacious early life, he not only took over the parenting of his younger sister but managed to support her and himself through graduate school. Despite his career disappointments, he knew his field well and had developed a wide range of competencies. Although his marriage had failed, he was a kind and loving person, devoted to his family and friends. His failures in both love and work appeared related to his perfectionism; he had been unable to accept anything less than an ideal world or perfect people, and he had let everyone know it. This attitude soured those around him, and he was often excluded from social get-togethers and passed over for promotions.

Paul’s painful realization at 50 was learning that he was a mere mortal. He would have to come to terms with not living up to his childhood fantasies before he would be able to achieve happiness and satisfaction in his real life. Paul would have to learn to love the real people in his life and accept the level of performance he and those around him were capable of attaining.

Paul’s therapy experience was arduous, but he gradually began to see through many of his illusions. In one session, Paul asked me, “How could I have lived 50 years and missed something so obvious, something that was right in front of my nose the entire time?” I thought for a while before offering some thoughts. “Our inner worlds are ageless and the defenses you developed as a young boy kept you going for half a century. Perhaps you are finally strong enough to face the pain of your childhood and learn to love and accept yourself for who you are. And from what I see, you are worthy of care, respect, and love.”

For many of us, later adulthood is a time when we finally find the insight, courage, and wisdom to exorcize old demons and learn new ways of being. As we age, we are better able to use both hemispheres when processing information. We come to be less driven by anxiety and we are better able to see through the distortions, biases, and impulsivity that can hamper us in adolescence and young adulthood. Enhancing centeredness, self-awareness, and mindfulness lie before us as evolutionary frontiers of consciousness.