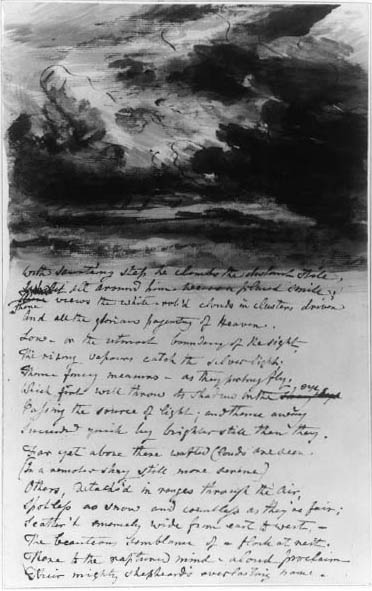

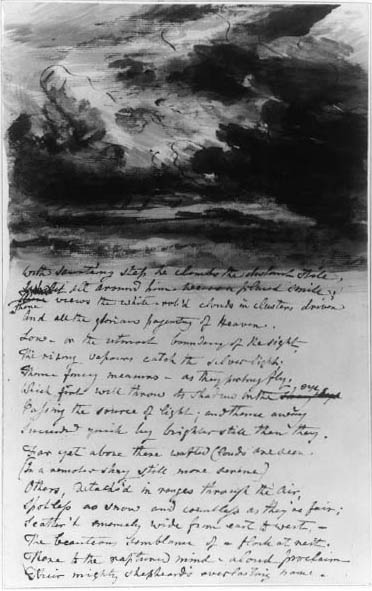

Constable copied a section from Robert Bloomfield’s poem, The Farmer’s Boy, to accompany his cloud study

DESPITE HIS CONCERN for his friend’s artistic success, John Fisher could be as self-absorbed and demanding as Constable. In August 1821 Fisher had decided that he needed a boat, to use on the Avon at the foot of Leydenhall garden. The obvious thing was to find one locally, new or second-hand, but Fisher reckoned it wouldn’t be too much of a chore for Constable to arrange the purchase. After all, he was a river man by birth and could find the right boat for him on the Thames. So Constable obligingly sent Fisher sketches of various types of small craft. He also went to some boatbuilders near Westminster Bridge and fixed on a sixteen-foot rowing skiff, price twenty-five guineas, including oars. At which point Fisher decided he didn’t have the money. Constable, in any event, had enough to do. Downtown he had rented a room from a glazier to use as a studio, where he was working on a large picture, presumably a preliminary study for A View on the Stour. In Hampstead he had also cleaned out the coal, mops and brooms from a shed at Lower Terrace for use as ‘a place of refuge’. Although Maria was ‘placid and contented’, and Mrs Roberts was now nurse and governess, two small children and a baby in the house created a zone of turmoil that could envelop the artist. The best refuge of all – the best place to get some sketching done – was out of doors, on the Heath.

At the end of summer and in the early autumn he frequently walked on to the Heath and looked upwards, then to his sketching paper pinned to the lid of his paintbox, again and again, drawing and painting. He wrote to Fisher on 20 September to say that he had ‘made many skies and effects … We have had noble clouds & effects of light & dark & color.’ He would have liked it said of himself, ‘as Fuseli says of Rembrandt, “he followed nature in her calmest abodes and could pluck a flower on every hedge – yet he was born to cast a stedfast eye on the bolder phenomena of nature.”’ And again, on 23 October: ‘I have done a good deal of skying … That Landscape painter who does not make his skies a very material part of his composition … neglects to avail himself of one of his greatest aids.’ Constable wasn’t the first artist to note this. Willem van de Velde the Younger, of the father-and-son team of marine painters who moved from Holland to England, used to have an old Thames waterman take him out on the Thames in all weathers, to study the sky. William Gilpin wrote: ‘These expeditions Vanderveldt called, in his Dutch manner of speaking, going a-skoying.’1 Charles Leslie said Van de Velde also used to go up to Hampstead Heath to observe the weather.2 Turner often walked out into the open and lay on the ground, looking up at the sky. Constable was therefore part of a tradition of painters taking supposedly picturesque elements and looking at them in naturalistic detail, defining their changes and differences. He looked harder and more precisely than most. And he noted that this knowledge would affect the complete painting. Constable continued his 23 October letter to Fisher by quoting Sir Joshua Reynolds on landscapes by Titian, Salvator Rosa, and Claude: ‘“Even their skies seem to sympathise with the Subject.” ’ Constable went on, ‘Certainly if the Sky is obtrusive – (as mine are) it is bad, but if they are evaded (as mine are not) it is worse, they must and always shall with me make an effectual part of the composition … The sky is the “source of light” in nature – and governs every thing.’

Perhaps he felt a bit guilty about this new obsession. Did Hampstead skies challenge his old watery loyalties? He told Fisher (in the same letter) that he had imagined himself with his friend on a recent trip which Fisher had made to fish in the New Forest. ‘But the sound of water escaping from Mill dams [moves me]’ – he omitted some words in his enthusiasm – ‘so do Willows, Old rotten Banks, slimy posts, & brickwork. I love such things … As long as I do paint I shall never cease to paint such Places.’ He would have been delighted to be with Fisher on his Hampshire river: ‘But I should paint my own places best – Painting is but another word for feeling. I associate my “careless boyhood” to all that lies on the banks of the Stour. They made me a painter (& I am gratefull) – that is I had often thought of pictures of them before I had ever touched a pencil …’

But skies were also an old interest. The apprentice at his father’s windmill on Bergholt Heath had learned to study the sky for portents of the changeable East Anglian weather – for calm, for gales, for reliable grain-grinding breezes. Years before he had read Leonardo’s Trattura, in which painters are advised to get inspiration from shapes seen on damp walls, in the embers of fires and in cloud patterns.3 Like many, he felt simple gratitude for sky, for clouds, for sunlight shining on and through them. Now on the relative heights of Hampstead he had open air and became a regular sky-watcher again: in 1821 and 1822 he painted nearly one hundred sky studies. He often took note of the exact time he made such sketches, involving an hour or so each, though the skies could change rapidly while he worked. The wind was ‘very brisk’ and the clouds ‘running very fast’, he recorded on one study, ‘very appropriate for the Coast at Osmington’. This was one of twenty Constable sky studies in oil that eventually came into Charles Leslie’s hands and which Leslie said were painted ‘on large sheets of thick paper, and all dated, with the time of day, the direction of the wind, and other memoranda on their backs’.4 Occasionally a thin strip showing land or tops of trees at the bottom of the sketch anchored the clouds and sky. Rarely a few birds wheeled. Most often the scudding, drifting or towering clouds and gaps of sky were the sole subject – and one could read (between the lines as it were) the weather of the moment – rain showers, impending thunder, clearing skies, the sun coming out. It was a completely different routine from that involved in assembling the parts of an exhibition six-footer – parts which were static, formed already in his memory or imagination. Here he was dealing with impressions – moving elements, parts of the air – while the wind stirred the grass around him and smoothed or dishevelled the sky above.

Hampstead was the perfect place for this activity. It was at a height, slight but meaningful, over London. It provided expansive prospects from a continuous elevation and little interference from dramatic scenery nearby. Here he could keep what was almost a visual journal, in Fisher’s words like Gilbert White ‘narrowly observing and noting down all the natural occurrences that came within his view’. Exactly what other meteorological scholarship of the time became part of his thinking is uncertain, but Luke Howard’s early essays and his Climate of London (1818–20), classifying different types of cloud, are in evidence. Howard named the clouds in a way which stuck; his Latinate term ‘cirrus’ has been made out by some experts on the back of one of Constable’s 1822 studies. Moreover, Constable wrote Howard’s name in notes he made while reading Thomas Forster’s Researches about Atmospheric Phaenomena, first published in 1813. Constable’s second-edition copy cost him six shillings. Its first chapter concerned the theories Howard expressed in his essays, and Constable’s annotations to it suggested his disagreement with many of Forster’s conclusions; one such note also uses Howard’s term ‘cumulostrati’. Later Constable wrote to a friend: ‘Forster’s is the best book – he is far from right, still he has the merit of breaking much ground.’ One quotation from Howard in Forster’s book drew attention to Robert Bloomfield’s poem of 1800, The Farmer’s Boy, a poem Constable later copied a long section from.5

Constable obviously didn’t intend to exhibit his cloud studies. They seem to be closely observed expressions of wonder at the beauty and variety of creation. He may also have thought they would be items in his armoury – material that he could employ when he needed ‘a sky’ for an exhibition painting. Yet he wasn’t totally successful in carrying over his spontaneous observations of skies into his finished pictures. Although in The Lock viewers can almost hear the air moving and the trees shaking, and in some paintings of Salisbury cathedral the tip of the spire – slicing the dark clouds that offended Bishop Fisher – seems to vibrate as the wind whistles around it, this wasn’t always the case. In The Hay Wain, the sky isn’t particularly inspired. We may of course think this because we have seen the picture too often, but Constable seems to have shared these doubts; he continued to work on the painting’s sky, after he got it back from the Academy, and, as if aware that he needed to do more aloft, embarked on his skying season in Hampstead at the same time.6

Constable copied a section from Robert Bloomfield’s poem, The Farmer’s Boy, to accompany his cloud study

In most of Constable’s pictures of this period the dynamic conditions are brilliantly suggested. In 1821 he made several pencil sketches of East Bergholt heath that provided material for an oil sketch on a wooden panel: windmill facing into the wind; racing low clouds; rooks wheeling; a ploughman firmly steering the plough pulled by a pair of heavy horses, locked to the spinning earth by gravity. And this eventually formed the basis for one of a series of mezzotint engravings of Constable’s works that he entitled ‘English Landscape’. For the plate called ‘Spring’ Constable wrote that it:

may perhaps give some idea of those bright and animated days of the early year … when at noon large garish clouds, surcharged with hail or sleet, sweep with their broad cool shadows the fields, woods, and hills; and by the contrast of their depths and bloom enhance the value of the vivid greens and yellows, so peculiar to this season … The natural history … of the skies … is this: the clouds accumulate in very large and dense masses, and from their loftiness seem to move but slowly; immediately upon these large clouds appear numerous opaque patches, which, however, are only small clouds passing rapidly before them … These floating much nearer the earth, may perhaps fall in with a stronger current of wind, which as well as their comparative lightness, causes them to move with greater rapidity; hence they are called by wind-millers and sailors ‘messengers,’ and always portend bad weather …

These clouds, wrote Constable, float midway in ‘the lanes of the clouds’ and are almost uniformly in shadow, receiving reflected light only from the clear blue sky above.

In several Hampstead pictures figures are to be seen walking along the ridge lines and near horizons, silhouetted against (and emphasising) the skies. Constable named some of the panoramic views from the Hampstead heights in a letter to Fisher of 3 November 1821, helping him with a circular diagram that showed the compass points. Hampstead was in the centre, St Alban’s to the north, Gravesend to the east, Dorking to the south, and Windsor to the west. He also drew Fisher’s attention to the presence of ‘the finest foregrounds – in roads, heath, trees, ponds &c’. The altitude had got to him. He told Fisher that he had been reading a life of Nicolas Poussin (by Maria Graham). Poussin, obviously an artist after his own heart, proved ‘how much dignity & elevation of character was the result of such patient, persevering and rational study – no circumstances however impropitious could turn him to the right or left – because he knew what he was about – & he felt himself above every scene in which he was placed’. One of the most striking Hampstead paintings was an oil sketch on paper (at some point affixed to canvas) called The Road to the Spaniards, taken from a dip in the road across the Heath leading to the Spaniards Inn, with some trees on the left amid which stood the house of the lawyer Anthony Spedding. It is a view seemingly from below ground level looking up to the top of the sandy track, with agitated thundery clouds tumbling above a few isolated people and animals. The horizon curves – there is a sense of the earth being round indeed. On the back a note records the atmospheric conditions of the day: ‘Monday 29 July 1822, looking NE, three hours after noon … a stormy squall coming from the north-west.’

A resident in Hampstead a few years before had been John Keats. Keats and Constable just missed each other, but they had much in common. Keats wrote to his brothers George and Thomas from Hampstead at the end of 1817, ‘The excellence of every Art is its intensity.’ And in a letter to Benjamin Haydon in April 1818, telling of his plans for a ‘pedestrian tour’ of the north of Britain, Keats exclaimed, ‘I will clamber through the Clouds and exist.’ Constable, clambering also above every scene in the locality, found a new province of his own kingdom on the Heath as he looked up at the clouds soaring past, dawdling, or stuck almost still. He strolled every day to Prospect Walk – now called Judges Walk – to try to capture the atmosphere re-making itself. On 3 September 1821 he painted ‘with large drops of rain falling on my palette’. On 10 September there was thunder and a heavy downpour. On the 11th, a brighter day, the small cumulus clouds were touched with sunlight. He painted the clouds at all sorts of angles, sometimes climbing, sometimes right overhead, sometimes parading directly at him in line ahead. Most of these sketches were oil on paper, and he sometimes made two a day.7 He wrote to Fisher a year or so after, taking his own obsession lightly, discussing having children, and punning on the similarity between nubile (meaning marriageable) and nubilous (by which he seems to have meant shady or cloudy, from Latin nubes, a cloud), he told the archdeacon: ‘You can never be nubilous – I am the man of clouds.’