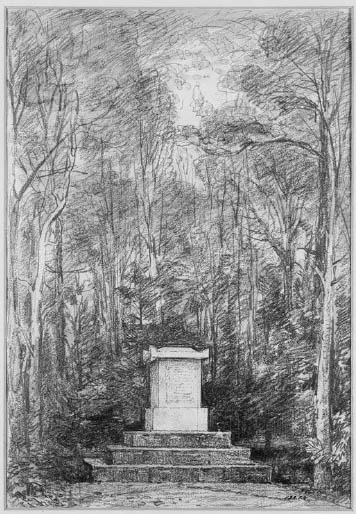

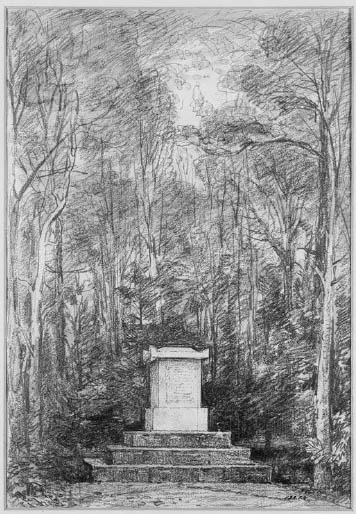

Memorial to Sir Joshua Reynolds at Coleorton, 1823

CONSTABLE HAD ONLY one complaint against Leslie: his good friend, even though back in the same city, lived too far away. His house in Pineapple Place was on the east side of Edgware Road, just beyond the old Kilburn Gate.1 It was on the edge of open country, with hayfields that extended to Harrow-on-the-Hill. Constable insisted the place was fatal to Leslie’s friendships, but nevertheless got himself there quite often. Leslie also came frequently to Hampstead or Charlotte Street. He dined with Constable on Christmas Eve 1834, when Samuel Rogers, David Wilkie and Jack Bannister were among the company. Leslie and Constable were different as artists but in some ways similar as men. What brought them together may have been that they were both somewhat out of the London swim and at a distance from their roots. Both favoured black clothing; both were warm individuals under a surface severity. Yet Leslie might not have taken to Constable if he hadn’t admired his paintings. He cultivated Constable’s friendship because he liked his art.2 And because Constable in turn liked Leslie so much – and felt for Leslie’s wife and children an immense affection, almost as if they were reflections of his own lost Maria and his own chicks – he admired Leslie’s paintings more than might have been expected. Leslie was essentially an illustrator, whose narrative pictures dealt with literary or historical subjects, such as his Uncle Toby and Widow Wadman or his Autolycus selling his wares. Constable lent him sky studies and, in March 1836, for the Autolycus sent him a rough sketch of a mountain ash he thought might be helpful. Leslie took the hint and introduced such a tree with its red berries to a sliver of landscape behind his shepherd and young woman.

In time Leslie would be accused of creating in his memoir too deferential a portrait of Constable, as if he were a superior being; but Leslie often wrote acutely about his friend. Although Constable didn’t have a very large circle of friends – or a great number of admirers of his pictures – they ‘compensated for their fewness by their sincerity and their warmth’. Leslie thought that Constable’s genius, in both his character and his art, didn’t suit his time. His stand-offishness was a problem, but despite it ‘no man more earnestly desired to stand well with the world; no artist was more solicitous of popularity’. On the one hand he desired approbation, on the other he couldn’t conceal the candid opinions that made people find him disagreeable. ‘What he said had too much point not to be repeated, and too much truth not to give offence; so some of his competitors hated him and most were afraid of him … He was opposed to all cant in art, to all that is merely specious and fashionable … He followed … his own feelings in the choice of subject and the mode of treatment. With great appearance of docility, he was an uncontrollable man.’ When people accuse Leslie of seeing Constable through rose-coloured spectacles, they should recall that remarkable epithet, ‘uncontrollable’.

Among Constable’s acquaintances at this time was Samuel Rogers, well known for his breakfast parties for the great, good, and talented at his house in St James’s Place, who was also to be encountered at Lord Egremont’s in Petworth along with Chantrey, Beechey, Turner, and Leslie. Constable had a memorable London morning with the banker-poet in March 1836. Rogers told Constable he was on ‘the right road’ as a landscape painter and that nobody could explain its history so well. Constable thought Rogers had the best private collection of paintings in London and particularly admired his Rubens. Rogers was pleased when Constable noticed the falling star in it. Constable watched his host feed some sparrows from the breakfast table; the sparrows seemed to know him well. Yet Rogers seemed also to tap into Constable’s dissatisfaction and melancholy. He told Constable that genius had to put up with the burden of being hated. Constable surprisingly demurred at this, though he agreed it could be true ‘in nature’. He wrote to Leslie afterwards, ‘I told him if he could catch one of those sparrows, and tie a bit of paper about its neck, and let it off again, the rest would peck it to death for being so distinguished.’3

The Royal Academy was in its final days at Somerset House. Leslie was on the Arrangement Committee in 1836 and Constable was pestered by ‘sparrows’ of a different sort, artists so-nicknamed who were hoping to get their works shown and who believed that a good friend of Leslie’s might sway the selection process. Some hopefuls sent not only supplications but their actual canvases to Charlotte Street, adding to the pressure on Constable. Among the ‘Hammatures’ (as he called them) seeking approval was the devoted Reverend Judkin; another was the French artist Auguste Hervieu, who had helped The White Horse get to Lille in 1825. Constable, aware from his own experience that he was being a nuisance, put in a word not only for Hervieu but for J.M. Nixon, a historical painter who had provided display placards for his lectures, for William C. Ross, a miniature artist, and for Samuel Lane, his old, handicapped, portrait-painting friend. That a painter was, like Nixon, ‘a kind and good father’, or like W.H. Fisk, from Thorpe-le-Soken in Essex, not far from the Stour, ‘a kind, good, amiable man’ (whose wife moreover had once made ‘some beautifull salve for Maria’s chilblains’), all made a difference to Constable, whose high standards vis-à-vis Berchem and Both didn’t come into play when it was a matter of the Academy and people he knew. However, his caustic tongue wasn’t completely subdued. One Brighton property owner, W.W. Altree, who was concerned to ensure that an architectural drawing of some villas he proposed to build was prominently hung, was – Constable told Leslie – ‘a great fool, and very ignorant, & forward in consequence’.

Constable entered two pictures for the exhibition, the last at Somerset House: The Cenotaph and Stonehenge, two sorts of monument. The first was a painting of a memorial to Sir Joshua Reynolds in the park of Coleorton Hall, but was also by the way a memorial to Sir George Beaumont, who had placed it there, and to the Academy itself. Constable had made a drawing of it back in November 1823, and wrote to Fisher about his visit: ‘In the dark recesses of these gardens … I saw an urn – & bust of Sir Joshua Reynolds – & under it some beautifull verses, by Wordsworth.’ The Beaumonts had laid the first stone for it on 30 October 1812, with Joseph Farington on hand. Constable had quoted Reynolds’s Discourses ten years before, to the effect that there was no easy way of becoming a good painter. In 1813 he had written to Maria about his liking for Reynolds’s paintings: ‘Here is no vulgarity or rawness and yet no want of life or vigor – it is certainly the finest feeling [for] art that ever existed.’ The Cenotaph, like The Valley Farm, is an elegiac, even funereal, painting, with a tiny robin and an alert deer the only life in it; the trees are bare, the sky mostly masked by their branches. Constable wrote to George Constable that it was ‘a tolerably good picture for the Academy, [though] not The Mill, which I had hoped to do … I preferred to see Sir Joshua Reynolds name and Sir George Beaumont’s once more in the catalogue, for the last time at the old house … The Exhibition is much liked. Wilkie’s pictures are very fine, and Turner has outdone himself; he seems to paint with tinted steam, so evanescent and so airy.’ The deer was probably meant to evoke Sir George’s fondness for As You Like It, the play set in the Forest of Arden, where melancholy Jaques observed a wounded stag.4

Memorial to Sir Joshua Reynolds at Coleorton, 1823

While he was at work on The Cenotaph two young brothers, Alfred and Robert Tidey, visited Constable. Robert, the younger of the artistically inclined pair, wrote later:

I was interested and amused by his mode of work and the way in which he produced such wonderful effects in his pictures by dabbing on splashes of colour with his palette knife in lieu of brush and stepping well back into the room now and again to view the result, remarking to my brother in an absent sort of way, ‘How will that do, Tidey, eh? How will that do?’ He seemed to me, as I believe he was, a man of extreme gentleness and simplicity of character.5

The Cenotaph got a fairly good press. Abram told his brother he heard well of it. Constable wrote to George Constable, ‘I hear it is liked, but I see no newspaper, not allowing one to come into my house.’ In fact, the Observer (with Edward Dubois departed) was coming on side: ‘The peculiar manner in which Mr Constable’s pictures are painted makes them appear singular at first, but by choosing a proper distance for observing them, by degrees the effect seems to grow upon us until we are astonished that we did not like them better before.’ The Times seemed to like the somewhat sententious lines by Wordsworth that Constable quoted in the catalogue more than the ‘singularly finished’ picture itself.6 But the Morning Herald and the Morning Post both approved of the painting, the latter deciding that ‘like all the pictures of Mr Constable, the present is marked by peculiarities, but they are the peculiarities of an original style, without the tricks of mannerism’. It was a word that kept coming up, even when it was being denied. Indeed, the Athenaeum thought the picture ‘less mannered’ than Constable’s works usually were; and Bell’s Weekly Messenger declared the painting had much beauty, albeit with ‘a singularity of style in the execution that rather approaches to mannerism’.7

As for his second offering, it was a watercolour which Constable had told Leslie about the previous September: ‘I have made a beautifull drawing of Stonehenge. I venture to use such an expression to you.’ Stonehenge was large for a watercolour, about fifteen by twenty-two inches. The standing, tilting, and fallen stones, and a few small figures, were spotlit against a tempestuous purple-black cloud with the inner and outer bands of a rainbow arching down in the background. (He told Lucas about this time that he had been ‘very busy with rainbows, and very happy doing them’.) A hare scuttled across the sheep-trimmed grass. In the Academy catalogue Constable described part at least of what he had in mind: ‘The mysterious monument of Stonehenge, standing remote on a bare and boundless heath, as much unconnected with the events of past ages as it is with the uses of the present, carries you back beyond all historical records …’ The watercolour made use of preliminary studies, two drawings and two watercolours, several of which he squared up for transfer, together with a pencil drawing he had done in 1820 while staying with the Fishers in which the great stones cast black shadows in the same way as the gnomon of a sundial. In the Academy watercolour he made the stones slightly smaller in terms of the whole picture, though the sky and weather increased the sense of surrounding drama. The contemplative shepherd and speeding hare offered a contrast to the stones: time present, time past. The hare seems to have been a late arrival; it was painted on a small piece of paper cut to a more or less hare-shape and pasted on. (Turner’s Mortlake Terrace of 1827 had a pasted-on dog; his Rain, Steam and Speed of 1844 contained a hare that seemed, like Constable’s, to suggest natural vitality.) Constable’s sky was unique; it showed no obvious influence of his 1820s sky studies. The Literary Gazette declared ‘the effect with which Mr Constable has judiciously invested his subject, is as marvelous and mysterious as the subject itself’. It is interesting to see him reinvolved with watercolours at this stage, perhaps finding them easier to manage than oils following his rheumatic fever.8

A farewell dinner for the Academy took place on 20 July in the Great Room at Somerset House after the close of the exhibition. Constable was on hand in ‘the dear old house’ along with the President. Sir Martin Archer Shee was about to defend the RA before a parliamentary committee inquiring into its procedures and Constable was among those who applauded Shee’s staunchness.9 (Haydon – no friend of the Academy – would give evidence in August before the committee and while he approved of the instruction in the Antique School, he totally disapproved of the rotating system of Visitors in the Life School, citing as an extraordinary example of the teaching methods ‘a very celebrated landscape painter’ who caused laughter by bringing in some lemon and orange trees and setting them round a naked Eve. Constable’s 1831 arrangement had, as noted, been popular with the students.)10 In any event, at the farewell dinner Constable dined with many of his fellows, including Wilkie, Callcott, Stanfield, Leslie, and Etty. Chantrey gave the toast: ‘The Old Walls of the Academy.’ Turner, believed to be opposed to the move to Trafalgar Square, was among the absentees. He had set off on one of his frequent summer tours abroad, this time through France to the Alps with Hugh Munro for company.11 The Academy Life School stayed on at Somerset House until March 1837 when it moved into the Academy’s new quarters in the same building as the National Gallery. Constable was one of the members chosen to be Visitors of the Life School in its last Somerset House session.

Constable was sixty on 11 June 1836. How old did he feel? He was looking forward to Charley’s return from his first voyage. Minna and Isabel were in Wimbledon and Constable visited them there, before they rejoined Emily, Alfred and Lionel with Mrs Roberts in Hampstead. Young John had gained a certificate for his chemistry studies and went off to spend five summer weeks at Flatford, ‘fishing and rowing all day and reading when it is wet’, his father told Emily in a letter from Charlotte Street written with a cat called Kellery perched on his shoulder. He went on, ‘A little black and white kitten was let down into the area in a woolen bag yesterday morning early’ – evidently by someone who knew the Constable family liked cats. ‘It is very thin … Kellery is very jealous.’12 Constable still hadn’t got up to Suffolk to see his new property. He delivered his last lecture in Hampstead on 25 July and arranged to have nine pictures sent to an exhibition in Worcester. The local paper there was struck by ‘the wonderful effect’ made by Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows – Summer Afternoon and A Farmyard by a Navigable River in Suffolk – Summer Morning, painted by ‘the same great master’.13

Charley had a short spell of shore leave when the Buckinghamshire docked. His first voyage had left its mark on the boy, so his father told George Constable in Arundel. ‘All his visionary and poetic ideas of the sea & a seaman’s life are fled – the reality now only remains, and a dreadful thing the reality is, a huge & hideous floating mass.’ Charley’s self-discipline and sense of order had been improved, however – ‘an advantage [to] a youth of ardent mind & one who has never been controlled’. The Buckinghamshire was now going to China. Constable paid a firm of shipping agents the sizeable sum of £75 for Charley’s accommodation and mess bills as a midshipman.14 He asked Lucas to send a copy of the new engraving of Dedham Vale (or the painting itself) so Charley could see it before he sailed, but if Lucas couldn’t manage this, ‘never mind – only he may never see it again’. Constable feared losing Charley rather than Charley losing him (his misgivings also surfaced in several ink sketches of ships in storms done at this time). Yet an awareness of the possibility of his own demise could be found in a profoundly gloomy letter written to a collector friend, a Mr Stewart – apparently a Hampstead neighbour – for whom he had painted a small picture of the Heath. Charley’s ship was still in the Thames estuary in late November, held up by bad weather rather than fog this time. Constable told Stewart that he himself was ‘so much invalided that I have not been allowed to leave the house … I am not in the best of spirits. The parting with my dear sailor boy – for so long a time that God knows if we ever meet again in this world – the various anxieties and the fear of the world, & its attacks on my dear children after I am gone & they have no protection, all these things make me sad.’ And he added, ‘I want to stick to my easil – but cannot.’15

When the Buckinghamshire got away, it was to run immediately into more fierce weather. Charley reported to his father shocking scenes in their storm-refuge anchorage off the Nore. Constable wrote to Leslie: ‘One large ship floated past them bottom upwards, & after the gale he saw 7 large hulls in tow with steamboats & some on the Goodwins [sandbanks] and some on the beach under the Foreland. The captain [Captain Hopkins again] gave him praise for his conduct in the weather mizen topsail ear-ring, and getting down the rigging in the gale, Charley’s post of honor.’ Constable felt fear, and pride, for Charley, and a vicarious excitement. He accompanied his words with a nervously messy little sketch of Charley’s station aloft, attending to the mizzen topsail. The sketch would have left Leslie little the wiser despite his passages with Captain Morgan – whose Philadelphia, Constable reported, was a miraculous survivor of the same storm.

Jack Bannister, good old friend, had died on 7 November; this didn’t improve Constable’s morale. There would be no more of Bannister’s songs and puns. Constable dined with Leslie and Wilkie on 1 December and recalled meeting Wilkie when they were students at the Academy. He remembered Wilkie saying that he was following his Scottish master’s advice, borrowed from Reynolds, to be industrious if you were short of genius. Wilkie was as modest as always and as usual seemed to put Constable into a nostalgic frame of mind.16 Wilkie around this time told Constable that he ought to paint ‘a large picture for over the line’ for the next Academy exhibition.17 Constable a week later heard from the collector and clothing manufacturer John Sheepshanks that he wanted Constable’s Glebe Farm, ‘one of the pictures on which I rest my little pretensions to futurity’. Would it be all right to ask 150 pounds for it, Constable enquired from Leslie. Sheepshanks’s gesture was generous, since Constable had just declined to paint a companion picture for a William Collins the collector owned, a painting which Constable said had ‘nothing to do with the art’. At Sheepshanks’s mansion in Blackheath he viewed the many pictures: Wilkie’s two looked beautiful; the more than a score of Mulreadys were ‘less disagreeable than usual’; Turner’s five were ‘grand’ but evidently not long for this world – some of his best work, said Constable, was ‘swept up off the carpet every morning by the maid and put onto the dust hole’.18

Constable was again in the midst of a tormented attempt to alter – or get Lucas to alter – a large mezzotint of Salisbury Cathedral. Dark clouds loomed behind the spire; the whole thing was ‘too heavy’. A number of corrections were still required in November. On 9 December he said the most recent proof was effective but ‘the flash of lightning over the north transept’ should be emphasised. On the last day of 1836, although he was once more sadly disturbed by the stormy sky, he couldn’t think why he had suggested a change. Lucas needed money and asked for a loan of two pounds. With an hour and a quarter to go before midnight, and 1837 imminent, Constable wrote enclosing two sovereigns and his good wishes to Mrs Lucas, who was about to have a baby. ‘God preserve your excellent wife, and give her a happy hour – I have not forgot my own anxieties at such a time though they are never to return to me.’ He ended with the words, ‘You have caused the Old Year to slip through my hands with pleasurable feelings … Farewell.’ But six weeks later the print, now called The Rainbow – Salisbury Cathedral, was still a bother. He wrote to Lucas, ‘I hope that obliging – and most strange & odd ruffian your printer, will be allowed to have just his own way in printing this plate – that is, now we see we must not be “too full.” It is as [he] says only fit for “a parcel of painters.” It will not be liked, any more than the English landscape, if it is too smutty.’19

Constable went for a New Year’s celebration at the Leslies’ on 2 January. For the Constable children it was like an ‘excursion into the country’. He insisted the Leslies allow him to return the hospitality two days later and that they come to share some venison the Countess of Dysart had sent. The other guests would be the family solicitor Anthony Spedding and Miss Spedding, who was fond of Minna.20 Constable closed his invitation with the words he said John Fisher had used to him in a request that he make a visit: ‘Prithee come – life is short – friendship sweet.’