3

The First Component: Exploring Health, Disease, and the Illness Experience

Moira Stewart, Judith Belle Brown, Carol L McWilliam, Thomas R Freeman, and W Wayne Weston

Health, Disease, and Illness

There is a long history documenting the failure of conventional medical practice in meeting patients’ perceived needs and expectations. Component 1 of the patient-centered clinical method addresses this failure by proposing that clinicians cast a wider gaze beyond disease, to include an exploration of health and the illness experience of their patients. In the earlier editions of this book we have elaborated on a conceptual distinction between disease and illness; in this edition, we add a third distinction: health.

This chapter is organized as follows. First, the terms used in this chapter are broadly defined: health, disease, and the illness experience. Then, their interconnectedness is described in a diagram. Next the clinical method, to help clinicians explore these issues with patients, is presented. Finally, the literature and powerful quotations justifying and elaborating the dimensions are provided – especially useful for the academic audience.

Effective patient care requires attending as much to patients’ perceptions of health and personal experiences of illness as to their diseases. Health, for the purposes of this chapter, is defined in a way that is akin to the most recent World Health Organization definition of a “resource for living,” which is among the several important concepts presented later in this chapter under the heading “Dimensions of Health: Relevance to Health Promotion and Disease Prevention.” We define health as encompassing the patients’ perception of health and what health means to them, and their ability to pursue the aspirations and purposes important to their lives.

Disease is diagnosed by using the conventional medical model by analysis of the patient’s medical history and objective examination of his or her body by physical examination and laboratory investigation. It is a category, the “thing” that is wrong with the body-as-machine or the mind-as-computer. Disease is a theoretical construct, or abstraction, by which physicians attempt to explain patients’ problems in terms of abnormalities of structure and/or function of body organs and systems and which includes both physical and mental disorders. Illness, for its part, is the patient’s personal and subjective experience of sickness: the feelings, thoughts, and altered function of someone who feels sick.

In the biomedical model, sickness is explained in terms of pathophysiology – abnormal structure and function of tissues and organs. “The medical model is materialist and assumes that the mechanisms of the body can be revealed and understood in the same way that the working of the solar system can be understood through gazing at the night sky” (Wainwright, 2008: 77). This model is a conceptual framework for understanding the biological dimensions of sickness by reducing sickness to disease. The focus is on the body, not the person. A particular disease is what everyone with that disease has in common, but the health perceptions and illness experiences of each person are unique. Disease and illness do not always coexist; health and disease are not always mutually exclusive. Patients with undiagnosed asymptomatic disease perceive themselves to be healthy and do not feel ill; people who are grieving or worried may feel ill but have no disease. Patients and practitioners who recognize these distinctions and who realize how common it is to perceive a loss of health or feel ill and yet have no disease are less likely to search needlessly for pathology. However, even when disease is present, it may not adequately explain the patient’s suffering, since the amount of distress a patient experiences refers not only to the amount of tissue damage but also to the personal meaning of health and illness.

Several authors have described similar distinctions among health, disease, and illness from different perspectives and these are presented in detail later in this chapter under the heading “Distinctions among Health, Disease, and the Illness Experience.”

Research has long supported the contention that disease and illness do not always present simultaneously. For some illnesses patients do not even seek medical advice (Green et al. , 2001; Frostholm et al. , 2005).

Many people present with medically unexplained symptoms. For example, more than a quarter of primary care patients in England have unexplained chronic pain, irritable bowel syndrome, or chronic fatigue, and in secondary and tertiary care, around a third of new neurological outpatients have symptoms thought by neurologists to be ‘not at all’ or only ‘somewhat’ explained by disease. (Hatcher & Arroll, 2008: 1124)

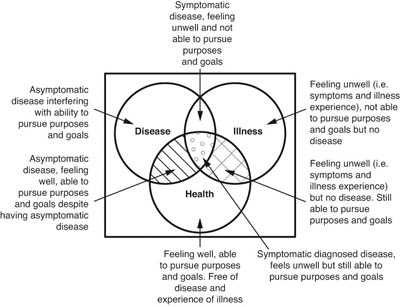

Figure 3.1 Overlap of health, disease, and the illness experience

In Figure 3.1, the patient with a sensation of being ill but having no disease is in the upper right-hand part of the Venn diagram or in the cross-hatched portion on the right. There are a variety of reasons for feeling ill but having no disease: the problem may be transient; it may be managed so early that it never reaches a diagnosis (e.g., impending pneumonia); it may be a borderline condition that is difficult to classify; the problem may remain undifferentiated; and/or the problem may have its source in factors such as an unhappy marriage, job dissatisfaction, guilt, or lack of purpose in life (McWhinney & Freeman, 2009). Patients falling into the group at the center of Figure 3.1, represented by the dots, where disease, illness, and health overlap, would have experiences of ill-health (sensory, cognitive, and emotional), a diagnosed disease and perceptions of their health, and what health means to them. For example, it is known that people with chronic disease may rate their health as good or very good despite having the disease. People in the center of the diagram have potential for health-enhancing attitudes and activities. The patient in the portion of Figure 3.1 with the diagonal lines in the left-hand overlap would have no feelings of ill-health but would have a diagnosed disease as well as perceptions of his or her health and what health means to him or her. Patients in the upper left-hand part of Figure 3.1 have a disease that is asymptomatic and also feel their disease interferes with their aspirations and life purposes. Examples of such patients may be those sometimes called partial patients, with high cholesterol, high blood pressure, high blood sugars (pre-diabetes or early diabetes).

The Clinical Method to Explore the Dimensions of Health

We propose that clinicians keep in mind the definition of health as being unique to each patient and encompassing not only absence of disease but also the meaning of health to the patient and the patients’ ability to realize aspirations and purpose in their lives. For one person health may mean being able to run in the next marathon; for another, health is when the back pain is brought under control.

Assuming the importance of the role of health promotion in all of health care, we recommend that clinicians ask persons coming to the clinic for periodic health examinations or minor ailments: “What does the term ‘health’ mean to you in your life?” Such questions adapted to the culture and individuality of each patient will serve two purposes clinically: first, the questions will reveal to the clinician previously unknown dimensions in the patient’s life; second, the questions will “develop the patients’ knowledge,” as Cassell (2013) says, a health-promoting act in itself. Some of the dimensions that the clinician may learn about (all are important as identified by the literature in this chapter under the heading “Dimensions of Health: Relevance to Health Promotion and Disease Prevention”) are the patient’s perceived susceptibility; his or her perceived health status and sense of well-being; his or her attitudes toward health consciousness and health behaviors; his or her perceptions of the benefits and barriers to health in his or her life; and the degree to which the patient feels he or she can create his or her own health, often called “self-efficacy.”

When patients are very sick, perhaps with chronic multimorbidities and experiencing hospitalizations, the clinician can explore the aspirations and purposes using the following types of questions taken from Cassell (2013: 89): “What is really bothering you about all this? … Are there things that you feel are very important that you want to do now … things that, if you got those done or started … you would have a better sense of well-being?”

The Clinical Method to Explore the Four Dimensions of the Illness Experience: FIFE

We propose four key dimensions of illness experience that practitioners should explore: (1) patients’ feelings, especially their fears, about their problems; (2) their ideas about what is wrong; (3) the effect of the illness on their functioning; and (4) their expectations of their clinician (see Figure 3.2).

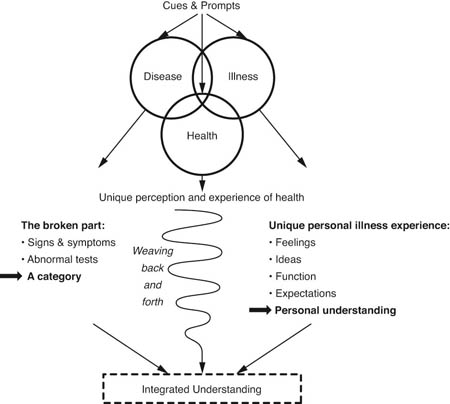

Figure 3.2 Exploring health, disease, and the illness experience

What are the patient’s feelings ? Does the patient fear that the symptoms he or she presents may be the precursor of a more serious problem such as cancer? Some patients may feel a sense of relief and view the illness as a reprieve from demands or responsibilities. Patients often feel irritated or culpable about being ill.

What are the patient’s ideas about his or her illness? On one level the patient’s ideas may be straightforward – for example, “I wonder if these headaches could be migraine headaches.” However, at a deeper level, patients may struggle to make sense of their illness experience. Many persons face illness as an irreparable loss; others may view it as an opportunity to gain valuable insight into their life experience. Is the illness seen as a form of punishment, or, perhaps, as an opportunity for dependency? Whatever the illness, knowing the patients’ explanation is significant for understanding the patient.

What are the effects of the illness on function ? Does it limit the patient’s daily activities? Does it impair his or her family relationships? Does it require a change in lifestyle? Does it compromise the patient’s quality of life by preventing him or her from achieving important goals or purposes?

What are the patient’s expectations of the clinician? Does the presentation of a sore throat carry with it an expectation of an antibiotic? Does the patient want the clinician to do something or just listen? In a review and synthesis of the literature on patient expectations of the consultation, Thorsen et al. (2001) provide a further conceptualization of patients’ expectations of the visit. They suggest that patients may come to a visit with their practitioner with “a priori wishes and hopes for specific process and outcome” (2001: 638). At times these expectations may not be explicit and, in fact, patients may modify or change their expectations during the course of the consultation.

The following examples of patient-practitioner dialogue contain specific questions that clinicians might ask to elicit the four dimensions of the patient’s illness experience.

- To the clinician’s question, “What brings you in today?” a patient responds, “I’ve had these severe headaches for the last few weeks. I’m wondering if there is something that I can do about them.”

- The patient’s feelings about the headaches can be elicited by questions such as: “What concerns you most about the headache? You seem anxious about these headaches; do you think that something sinister is causing them? Is there something particularly worrisome for you about the headaches?”

- To explore the patient’s ideas about the headaches, the clinician might ask questions such as: “What do you think is causing the headaches? Have you any ideas or theories about why you might be having them? Do you think there is any relationship between the headaches and current events in your life? Do you see any connection between your headaches and the guilty feelings you have been struggling with?”

- To determine how the headaches may be impeding the patient’s function , the clinician might ask: “How are your headaches affecting your day-to-day living? Are they stopping you from participating in any activities? Is there any connection between the headaches and the way your life is going?”

- Finally, to identify the patient’s expectations of the practitioner at this visit, the clinician might ask: “What do you think would help you to deal with these headaches? Is there some specific management that you want for your headaches? In what way may I help you? Have you a particular test in mind? What do you think would reassure you about these headaches?”

As the following case illustrates, listening to the patient’s story and exploring the disease and illness experience are essential aspects of patient-centered care.

Case Example

At 3 a.m. Jenna Jamieson was awakened by a sharp pain in her right lower quadrant. She dismissed it as bothersome menstrual pain and tried to get back to sleep. However, sleep was not an option, as the pain became unremitting.

Jenna was a 31-year-old single woman who lived alone. A committed teacher of special needs children she had just begun working at a new school. She was also an accomplished rower who had led her team to several national victories. At 3:30 a.m. Jenna, feeling feverish and nauseated, staggered to the bathroom. In her stupor of pain she was thankful on two counts: it was Saturday – at least she would have a couple of days to recover from whatever this was before returning to school – and being winter there was no rowing practice.

By 6 a.m. the pain had reached the point that Jenna could hardly get her breath. She felt weak, sweaty, and nauseated. In desperation Jenna called a close friend to take her to the hospital.

Three hours later, after undergoing numerous tests and examinations, the surgeon on call diagnosed acute appendicitis. Jenna was promptly taken to the operating room for surgery. While medication had alleviated Jenna’s pain, her anxiety and fear had intensified. In a few brief hours she had gone from feeling healthy and vital to someone who was very ill.

In the recovery room Jenna felt groggy and disoriented. She sighed and then blinked to see her surgeon standing over her. “Well, Jenna” he said “It was not your appendix after all. In fact it was a bit more serious.” Jenna had had a Meckel’s diverticulitis requiring a partial bowel resection. Because it had ruptured and she developed peritonitis, she would be in hospital for several days for intravenous antibiotics. Her recovery would require at least 4–6 weeks. The diagnosis was a shock and the surgery had been intrusive. Jenna found it hard to comprehend how all this had transpired and to some extent she denied her current reality.

Daily, her surgeon came to see her and offer support. On one occasion, sensing her irritability, he asked Jenna if she was angry. While initially surprised by his question, upon reflection Jenna realized that she was angry and also felt as if her once healthy body had betrayed her. She was struggling to make sense of why this had happened. Her life had been turned upside down and the things that were important to her were now even more precious. She missed her students and her work and wondered if she would have the physical stamina to return to work. She was also fearful that her other passion, rowing, would have to be forsaken – at the pinnacle of her career. Her team was so close to an international victory – an event she might now miss.

Jenna’s surgeon listened and understood her anger and fears. He did not dismiss them or render them superfluous. Rather, he validated Jenna’s concerns and reassured her that she would be able to enjoy all her activities and zest for living. These actions on the part of the doctor were central to Jenna’s recovery. The doctor’s acknowledgment of her present anger and future fears assisted in Jenna’s own self-knowledge and belief in becoming well again. Had the surgeon only focused on her disease, her emotional recovery could have been delayed. Exploring Jenna’s unique illness experience and supporting her through the recovery period to regain her health was as essential to her care as the surgical intervention.

Certain illnesses or events in the lives of individuals may cause them embarrassment or emotional discomfort. As a result, patients may not always feel at ease with themselves or their clinician and may cloak their primary concerns in multiple symptoms. The doctor must, on occasion, respond to each of these symptoms to create an environment in which patients may feel more trusting and comfortable about exposing their concerns. Often, the doctor will provide them with an avenue to express their feelings by commenting: “I sense that there is something troubling you or something more going on. How can I help you with that?”

Identifying how to ask key questions ought not to be taken lightly. Malterud (1994) has described a method for clinicians to formulate and evaluate the most effective wording of key questions. By trying out different wording, the physician was able to discover key questions with wording that facilitated patients answering questions that they had previously avoided. For example:

By including … ‘let me hear’ … or … ‘I would like to know’ …, I heard myself signalling an explicit interest towards the patient’s thoughts … When asking the women directly about their expectations, they often responded – somewhat embarrassed: … ‘I thought that was up to the doctor to decide …’ The response became more abundant when I hinted that she surely had been imagining what might happen (… ‘of course you have imagined ’ …).” (Malterud, 1994: 12)

Key questions were usually open-ended, signalled the doctor’s interest, invited the patient to use her imagination and conveyed that the doctor would not withdraw from medical responsibility.

The following case provides another illustration of the patient-centered clinical method and explicitly describes dimensions of health, disease, and the illness experience.

Case Example

Mr Rex Kelly was a 58-year-old man who had been a patient in the practice for 10 years. He had been a healthy man with few problems until 8 months ago, when he had a massive myocardial infarction and required triple coronary artery bypass surgery. He was married, with grown children, and he worked as a plumber. He had come to the office for diet counseling about his elevated cholesterol.

The following excerpt from the visit demonstrates the doctor’s use of the patient-centered approach. The interaction began with Dr Wason stating, “Hi Rex, I’m glad to see you again. I understand you are back to check on your progress since your heart attack. Is there anything else you would like to discuss today?”

“That’s right, doc, I’m sticking to our plan. I’m feeling pretty good about my weight. I’m down 5 more pounds and almost at my goal. I’m wondering how my last cholesterol turned out.”

“Congratulations, Rex, you have done really well with the diet and that has helped bring down your cholesterol – it’s now almost at the target level, too.”

The interview then shifted to Rex’s exercise program, and he stated that he had been regularly following his exercise regimen throughout the summer months and was walking up to 4 miles a day. Dr Wason asked, “Will you be able to continue your walking during the winter?”

“I think so,” indicated Rex. “I don’t mind walking in the winter as long as it’s not too cold.”

“Yes, you do need to be cautious during the severe weather,” replied Dr Wason. Rex looked away and appeared sad. The doctor paused and asked, “Is there something concerning you, Rex?”

“Oh well … no,” stated Rex quickly. “No, not really.”

“Not really?” reflected Dr Wason.

“Well,” replied Rex, “I was just thinking about the winter and … well … no, I guess I’ll be able to snowmobile if I just keep warm.”

“Why are you concerned that you won’t be able to do that, Rex?” asked the doctor.

“Well, I don’t know. I’d just miss it if I couldn’t participate.”

“It sounds as if that activity is important to you,” responded Dr Wason.

“Well, yes, it has been a very important family activity. We have some land and a little cabin up north of here, and it’s really how we spend our winter weekends – the whole family together.”

“It sounds as if not being able to participate in something that’s been an important family activity would be very difficult for you,” reflected the doctor.

“Yes, it would be. I just feel that so many things have been taken away from me that I really would miss not being able to do that.”

The doctor responded, “Rex, during the last several months you have experienced a lot of changes and a lot of losses. I sense it has been very difficult for you.”

Rex solemnly replied: “Yes, doc, it has. It’s been tough. I’ve gone from being a man who is really healthy and has no problems to having a bad heart attack and a big operation and being a real weight watcher. And I still don’t have the energy I used to have and sometimes I worry about having another heart attack. And my wife is worried too – she is always reminding me to be careful and we are both anxious about resuming our lovemaking. It has been a big change, and it has had its tough moments, but I’m alive and I guess that is what matters.”

“It seems that you – and your wife too – still have a lot of feelings surrounding your heart attack and the surgery and the changes that have occurred,” observed Dr Wason.

“Yes, we have,” Rex noted soberly, “… we have.”

“I’m glad I can tell you that you have passed the most dangerous period after your heart attack and now your risk is quite low. In some ways, because of your better diet and regular exercise, you are healthier than you were before your heart attack. That’s good news, but I am concerned about your sadness and wonder if it would be helpful at your next appointment for us to talk about that more, to set aside some time just to look at that?” inquired Dr Wason.

“Yes it would. It’s hard to talk about, but it would be helpful,” Rex answered emphatically.

“Are you encountering any problems with sleep or appetite Rex?” asked the doctor.

“No, none at all,” stated Rex.

The doctor asked a few more questions exploring possible symptoms of depression. Finding none, he again offered to talk further with Rex at their next visit and suggested it might be helpful to invite his wife to an upcoming appointment. The patient answered affirmatively.

In this example the patient’s situation can be summarized by using the health, illness, and disease framework, which is part of the patient-centered model illustrated in Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3 The patient-centered clinical method applied

The doctor already knew the patient’s medical conditions before the interview began. He picked up on the patient’s sadness and his initial hesitancy in exploring how the heart attack had made him fearful. At the same time, the doctor ruled out serious depression by asking a few diagnostic questions and offered the patient an opportunity to explore further his feelings about his health and illness experience. Also the doctor and patient explored the patient’s aspirations for a healthy life, in his case including snowmobiling with his family and resuming lovemaking. The reader will notice that the interview effortlessly weaved among the disease, health, and the illness experience.

By considering the patient’s health and illness experience as a legitimate focus of enquiry and management, the physician has avoided two potential errors. First, if only the conventional biomedical model had been used, by seeking a disease to explain the patient’s distress, the doctor might have labeled the patient depressed and given him unnecessary and potentially hazardous medication. A second error would have been simply to conclude that the patient was not depressed and move on to the next part of the interview. Had the physician decided that the patient’s distress was not worthy of attention, he might have delayed the patient’s emotional and physical recovery and the patient’s adjustment to living with a chronic disease.

This case also illustrates that, although medical management after a myocardial infarction has improved considerably in recent years, it is not enough to limit treatment to the biological dimensions of the problem. This patient was following all of the guidelines but he still did not feel healthy or secure in his body. Also, his fears were shared by his wife, thus compounding his anxiety. Dealing with this patient’s experience of health and illness, and including his wife in the discussions, may be helpful in promoting health, alleviating fears, correcting misconceptions, encouraging him to discuss his discouragement, or simply “being there” and caring what happens to him. At the very least, this compassionate concern is a testimony to the fundamental worth and dignity of the patient; it might help prevent him from becoming truly depressed; it might even help him to live more fully.

Distinctions among Health, Disease, and the Illness Experience

In analyzing medical interviews, Mishler (1984) identifies contrasting voices: the voice of medicine and the voice of the lifeworld. The voice of medicine promotes a scientific, detached attitude and uses questions such as: Where does it hurt? When did it start? How long does it last? What makes it better or worse? The voice of the lifeworld, on the other hand, reflects a “commonsense” view of the world. It centers on the individual’s particular social context, the meaning of health and illness, and how they may affect the achievement of personal health goals. Typical questions to explore the lifeworld include: How would you describe your health? What are you most concerned about? How does your loss of health disrupt your life? What do you think it is? How do you think I can help you?

Mishler (1984) argues that typical interactions between doctors and patients are doctor-centered – they are dominated by a technocratic perspective. The physician’s primary task is to make a diagnosis; thus, in the interview, the doctor selectively attends to the voice of medicine, often not even hearing the patient’s attempts to make sense of his or her suffering. What is needed, he maintains, is a different approach, in which doctors give priority to “patients’ lifeworld contexts of meaning as the basis for understanding, diagnosing and treating their problems” (Mishler, 1984: 192).

In a qualitative study, Barry et al. (2001) applied Mishler’s concepts in the analysis of 35 case studies of patient-doctor interactions. Their findings revealed an expansion of Mishler’s ideas, adding two communication patterns: “lifeworld ignored,” where patients’ use of the voice of the lifeworld was ignored, and “lifeworld blocked,” where doctors’ use of the voice of medicine blocked patients’ expressions of the lifeworld. These two communication patterns were found to have the poorest outcomes. When both the patient and the doctor used the voice of medicine exclusively, Barry et al. (2001) called this “strictly medicine,” as the emphasis was on simple, acute physical complaints. “Mutual lifeworld” was the term applied to interactions where both the patient and the doctor used the voice of the lifeworld, thus highlighting the uniqueness of the patient’s life and experience. Of note, Barry et al. (2001) found that the best outcomes were in patient-doctor encounters categorized as either “mutual lifeworld” or “strictly medicine.” They offer four possible interpretations of the latter finding: (1) the patient has come to view his or her problems from the perspective of the voice of medicine; (2) the patient has learned from experience that the voice of the lifeworld has no value in medical encounters; (3) the patient is goal oriented in these encounters and wants a quick, efficient encounter; and, finally, (4) the structure of these encounters is such that the patient has no opportunity to use the voice of the lifeworld. Because the encounters incorporating “mutual lifeworld” reflected excellent outcomes, too, Barry et al. (2001) conclude that doctors need to be sensitized to the importance of attending to patients’ concerns of the lifeworld.

Typically, when patients become seriously ill, they find some way to make sense of it – they may blame their own bad habits (eating too much, not exercising enough); they may blame fate or bad luck; or they may attribute it to “bad genes” or environmental toxins; some may even believe they have been cursed. Patients’ “explanatory models” are their own personal conceptualizations of the etiology, course, and sequelae of their problem (Green et al. , 2002). Medical anthropologists such as Kleinman have described ways to elicit the patients’ “explanatory models” of their illness and offer a series of questions to ask patients – a “cultural status exam.” The physician might ask, for example: “How would you describe the problem that has brought you to me? Does anyone else that you know have these problems? What do you think is causing the problem? Why do you think this problem has happened to you and why now? What do you think will clear up this problem? Apart from me, who else do you think can help you get better? What do you think you could do to feel healthy?” (Kleinman et al. , 1978; Galazka & Eckert, 1986; Katon & Kleinman, 1981; Good & Good, 1981; Helman, 2007).

The following views on the importance of distinguishing between health, disease, and illness are offered from the perspective of the patient and the doctor. The patient is Anatole Broyard, who taught fiction writing at Columbia University, New York University, and Fairfield University. An editor, literary critic, and essayist for the New York Times , he died from prostate cancer in October 1990.

I wouldn’t demand a lot of my doctor’s time. I just wish he would brood on my situation for perhaps five minutes, that he would give me his whole mind just once, be bonded with me for a brief space, survey my soul as well as my flesh to get at my illness, for each man is ill in his own way … Just as he orders blood tests and bone scans for my body, I’d like my doctor to scan me, to grope for my spirit as well as my prostate. Without some such recognition, I am nothing but my illness. (Broyard, 1992: 44–5)

The doctor is Loreen A Herwaldt, an internist and epidemiologist in Iowa.

The big lesson for me was learning the difference between treating the disease and treating the human being. It’s not always the same thing. There are times you can kill the person – in a sense, killing their spirit – by insisting that something be done a certain way. (Herwaldt, 2001: 21)

Eric Cassell (2013) challenges physicians to broaden their concept of their role to include a careful assessment of how disease impairs the patient’s function:

The focus is wider. Knowing the disease, the healer is concerned with establishing the functional status of the patient – what the patient can and cannot do. What is interfering with the accomplishment of the patient’s goals? How does the patient attempt to surmount these impairments? (2013: 126)

He suggests expanding the scope of questions:

“Fatigue (or dyspnea, heartburn, or abdominal pain)?” “Does that get in your way?” or “Does that interfere in your life?” “How?” “Tell me about it.” (2013: 128)

We are trying to uncover anything in any dimension of the patient’s existence that is interfering with the patient’s ability to achieve his or her goals or purposes. In what sphere do we find these purposes? Those in which people strive to make life worth living. For example, love and human connections – does the patient feel left out, isolated, wanted, or loved … Of a belief that there are things larger and more enduring than the self – fulfilling purposes in work (e.g., medicine, art, machine shop, or finance), social existence, or family. This is expressed in the ability to communicate, be creative, or fulfill expectations of the self or others and in doing things that the patient has identified as important, or other things that are central to particular individuals. (2013: 129)

Common Responses to Illness

The reasons patients present themselves to their practitioners when they do are often more important than the diagnosis. Frequently the diagnosis is obvious or it is already known from previous contacts; often there is no biomedical label to explain the patient’s problem. Thus, it is often more helpful to answer the question “Why now?” than the question “What’s the diagnosis?” In chronic illness, for example, a change in a social situation, or a change in the internal sense of health agency/control, are more common reasons for presenting than a change in the disease or the symptoms.

Illness is often a painful crisis that will overwhelm the coping abilities of some patients and challenge others to increased personal growth (Sidell, 2001; Wainwright, 2008; Marini & Stebnicki, 2012; Lubkin & Larsen, 2013). Livneh and Antonak (2005) describe common negative psychological responses to chronic illness and disability.

Increased stress is experienced because of the need to cope with daily threats to (a) one’s life and well-being; (b) body integrity; (c) independence and autonomy; (d) fulfillment of familial, social, and vocational roles; (e) future goals and plans; and (f) economic stability. (2005: 12)

A sudden disability or life-threatening diagnosis creates a crisis that upsets the patient’s equilibrium and may be long-lasting. This triggers a mourning process over the loss of body part or function that serves as a constant reminder of the impairment. Unsuccessful adaptation to the loss may lead to chronic anxiety, depression, social withdrawal, and distortion of the body image. Self-concept and identity may be damaged. Patients with chronic disease may be stigmatized, resulting in social withdrawal and reduced self-esteem. Many medical conditions are unpredictable and lead to a life of uncertainty. Quality of life is often diminished.

It is helpful to understand these reactions as part of a predictable process described by Strauss and colleagues as a “trajectory framework” or “biography” (Glaser & Strauss, 1968; Strauss & Glaser, 1970). “The trajectory is defined as the course of an illness over time, plus the actions of clients, families, and healthcare professionals to manage that course” (Corbin & Strauss, 1992: 3). Even for persons with the same disease, the illness trajectory will be unique for each individual based on the strategies that the individual uses to manage his or her symptoms, illness beliefs, and personal situation.

During the trajectory phase, signs and symptoms of the disease appear and a diagnostic workup may begin. The individual begins to cope with implications of a diagnosis. In the stable phase, the illness symptoms are under control and management of the disease occurs primarily at home. A period of inability to keep symptoms under control occurs in the unstable phase. The acute phase brings severe and unrelieved symptoms or disease complications. Critical or life-threatening situations that require emergency treatment occur in the crisis phase. The comeback phase signals a gradual return to an acceptable way of life within the symptoms that the disease imposes. The downward phase is characterized by progressive deterioration and an increase in disability or symptoms. The trajectory model ends with the dying phase, characterized by gradual or rapid shutting down of body processes. (Corbin, 2001: 4–5)

Reiser and Schroder (1980) describe a similar model of illness that has three stages: awareness, disorganization, and reorganization. The first stage, awareness, is characterized by ambivalence about knowing: on the one hand, wanting to know the truth and to understand the illness; on the other hand, not wanting to admit that anything could be wrong. At the same time patients are often struggling with conflicting wishes to remain independent and longing to be taken care of. Eventually, if the symptoms do not go away, the fact of the illness hits home and the patient’s sense of being in control of his or her own life is shattered.

This disrupts the universal defense – the magical belief that somehow we are immune from disease, injury, and death. The patient who has struggled to forestall his awareness of serious illness and then has finally recognized the truth is one of the most fragile, defenseless, and exquisitely vulnerable people one can ever find. This is a time of terror and depression and reflects the second stage, disorganization (Reiser & Schroder, 1980).

At this stage, patients typically become emotional and may react to their caretakers as parents rather than as equals. They often become self-centered and demanding, and although they may be aware of this reaction and embarrassed by it, they cannot seem to stop it. They may withdraw from the external world and become preoccupied with each little change in their bodies. Their sense of time becomes constricted and the future seems uncertain; they may lose a sense of continuity of self. They can no longer trust their bodies, and they feel diminished and out of control. Their whole sense of their personal identities may be severely threatened. One reaction to this state of mind in some patients is rebellion, a desperate attempt to have at least some small measure of control over their lives even if it is self-destructive in the end.

The third stage is reorganization. In this stage patients call upon all of their inner strengths to find new meaning in the face of illness and, if possible, to transcend their plight. Their degree of mastery and sense of health and capability, in spite of a disease, will be affected by the nature and severity of the disease. However, in addition, the outcome is profoundly influenced by the patients’ social supports, especially loving relationships within their families, and by the type of support their physician can provide.

These stages of illness are part of a normal human response to disaster and not another set of disease categories or psychopathology. This description emphasizes how the humanity of the ill person is compromised and points to an added obligation of physicians to their wounded patients.

So great is the assault of illness upon our being that

it is almost as if our natures themselves were ill, as if the strands or parts of us were being forced apart and we verged on the loss of our own humanness. A phenomenon so great in its effects that it can threaten us with the loss of our fundamental humanness clearly requires more than technical competence from those who would ‘treat’ illness. (Kestenbaum, 1982: viii–ix)

Stein (2007) describes four common feelings that accompany serious illness: terror, loss, loneliness, and betrayal. Understanding these predictable responses to illness can help prepare both patients and physicians for the struggles that patients may experience in attempting to come to terms with the impact of disease on their bodies and their lives. “Terror is the beginning of the end of the illusion that illness isn’t that bad” (2007: 95). Losses associated with illness come one after another and sometimes feel endless. “Disfigurement offers the most literal understanding of loss, of change, of the fragility and vulnerability of the body” (2007: 165). Stein refers to the unbearable loneliness of serious illness, how patients conceal their struggles with pain or chemotherapy without revealing the fears and many inconveniences illness brings. Betrayal refers to the feeling that the body has let the patient down – it can no longer be trusted or counted on to let the patient do what matters to him or her. Stein describes betrayal this way:

Health is familiar, predictable, reliable, and, we hope enduring. It provides a sense of orientation. Illness is a break in the established, continuous sameness and comfort of health. Betrayal arrives without arrangement, unpredictably, spontaneously, carrying danger. It is a threat, and we are vulnerable. It has revealed a secret about us. Personal worth and value are undermined. All of us idealize our own bodies (even if not every piece of them) so we are deeply disappointed by illness. We are strong and vigorous one moment, helpless the next; we have power one moment and are without it the next. We take account of our assets and resources, but when betrayed, we feel useless. (2007: 61)

Case Example

It all happened in a flash, or so Brenna thought. One day Brenna felt well, in her sailboat flying over the waves at the end of summer, and the next she was not. Fall had ascended – in so many ways.

Brenna had suffered an aneurism at the age of 47. She had been fit, healthy, and fully employed in the health care field. Now she was a patient, hospitalized and helpless. While headaches were not foreign to her, the headache she awoke with “at the onset of the episode” did feel unusual. However, she quickly passed it off. Brenna was not one to succumb to such inconveniences – or to appear weak and vulnerable.

With the holiday weekend coming to a close, Brenna had diligently secured the sailboat, pushing the pain in her head aside, and began the trip back to the city. “Perhaps a coffee would help,” she reflected. It did not. An hour later, just as Brenna was turning off the highway, she lost control of her car and ripped through 13 guardrails on the exit ramp. The car was demolished but she was alive. Her next memory, although vague, was being in a white, sterile room in the hospital. Her head felt like it was about to explode.

Brenna had limited memories of the car accident or the events that followed. She struggled to make sense of the time line that expired over this short but very significant period in her life. While others, family and friends, said “Don’t fret about it – that’s the past, move on,” she could not. Her past was connected to her future. Brenna could not ignore it or dismiss it as meaningless. It had meaning to her – meaning that radically informed who she was – today and what her future held. Because, at that moment, her future was uncertain.

From the outset, Brenna’s neurologist, Dr Menin, had been kind and informative. The surgical team who repaired her aneurism were superlative in their handiwork. The neuropsychologist was efficient and also supportive. Brenna’s health care team provided her with “optimal medical care.” She recognized the initial denial she experienced regarding both the life-threatening diagnosis and the serious nature of the surgical procedure to repair her aneurism. However, she survived and was now on a journey to understand the neurological deficits she experienced and how they would change her life.

Months have now passed and, as the memories of that horrific assault on her brain and her personhood are slowly and painfully receding, she still struggles to understand what has happened. Brenna wonders, not “Why did this happened to me?” but rather, “Who have I become?” “Am I a sick person?” “Am I now disabled?” “What do these labels really mean – do they actually now define me as a person?”

Patients’ Cues and Prompts

Patients often provide physicians with cues and prompts about the reason they are coming to the physician that day. These may be verbal or nonverbal signals. The patients may look tearful, sigh deeply, or be breathless. They may say directly, “I feel awful, Doctor. I think this flu is going to kill me.” Or, indirectly, they may present a variety of vague symptoms that are masking a more serious problem such as depression. Other authors have described patients’ cues and prompts using different terminology, such as clues (Levinson et al. , 2000; Lang et al. , 2000) or offers (Balint, 1964), but regardless of the name assigned, the patient behaviors are the same. Lang et al. (2000) describe a useful taxonomy of clues revealed in patients’ utterances and behaviors reflecting their underlying ideas, concerns, and/or expectations:

- expression of feelings (especially concern, fear, or worry)

- attempts to understand or explain symptoms

- speech clues that underscore particular concerns of the patient

- personal stories that link the patient with medical conditions or risks

- behaviors suggestive of unresolved concerns or expectations (e.g., reluctance to accept recommendations, seeking a second opinion, early return visit).

Levinson et al. (2000) define

a clue as a direct or indirect comment that provides information about any aspect of a patient’s life circumstances or feelings. These clues offer a glimpse into the inner world of patients and create an opportunity for empathy and personal connection… . [thus] physicians can deepen the therapeutic relationship. (2000: 1021)

In order to assess how primary care physicians and surgeons respond to patient clues they assessed 116 patient-doctor encounters (54 of primary care physicians and 62 of surgeons). Through their qualitative analysis, Levinson and colleagues found that patients initiated the majority of clues and most were emotional in nature. The physicians frequently missed opportunities to adequately acknowledge patients’ feelings, and as a result some patients repeatedly brought up the clue only to have it ignored again and again.

Thus as doctors sit down with patients and ask them, “What brings you in today?” they must ask themselves, “What has precipitated this visit?” They need to listen attentively to patients’ cues not only of their diseases but also of their experience of illness and their perceptions of their health. Of equal importance to hearing patients’ cues and prompts are empathic responses that help patients feel understood and recognized.

Narratives of Health and the Illness Experience

A growing number of publications illustrate the importance of patients’ narratives – in particular, their recounting of their story of illness (Greenhalgh & Hurwitz, 1998; Launer, 2002; Sakalys, 2003; Charon, 2004, 2006, 2007; Nettleton et al. , 2005; Haidet et al. , 2006; Greenhalgh, 2006; Brown et al. , 2012a; Herbert, 2013). As Arthur Kleinman (1999) observes, narratives of illness, the patients’ stories of being unwell, open up untold vistas of experience and knowing.

Stories open up new paths, sometimes send us back to old ones, and close off still others. Telling (and listening to) stories we too imaginatively walk down those paths – paths of longing, paths of hope, paths of desperation. We are, actually, all of us, physicians and patients and family members too, storied folk: stories are what we are; telling and listening to stories is what we do. (Kleinman, 1999: x)

Hunter’s (1991) vision of the narrative expands this view, in that the story is not one-sided but involves two (and we suggest multiple) protagonists or story-tellers. “Understanding medicine as a narrative activity enables us – both physicians and patients – to shift the focus of medicine to the care of what ails the patient and away from the relatively simpler matter of the diagnosis of disease” (Hunter 1991, p. xxi). Expanding the focus of inquiry from simply the disease to include the patient’s health and illness experience can provide a richer, more meaningful, and more productive outcome for all participants.

Yet research spanning almost 30 years (Beckman & Frankel, 1984; Marvel et al. , 1999; Rhoades et al. , 2001) indicates that physicians interrupt patients’ accounts of their symptoms early in the consultation and hence their stories of health and illness are often untold. This reflects a failure on the physicians’ part to weave back and forth between exploring the disease and illness experience, following the patients’ cues. The patients’ story of a troublesome sore throat may cloak their fear that this is a precursor to cancer, or patients may minimize their severe shortness of breath, explaining it as allergies, which, from the doctor’s perspective, may indicate a more severe medical problem such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

However, when clinicians assist patients to tell their story of health and illness, they are helped to gain meaning, and ultimately mastery, of their health and illness experience (Stensland & Malterud, 2001). When patients do not have a voice in the consultation, important dimensions of their health and illness experience, such as their feelings and ideas, will not be expressed (Barry et al. , 2000). Of equal concern is the potential for problematic outcomes such as nonuse of prescriptions and nonadherence to treatment (Barry et al. , 2000; Dowell et al. , 2007). Thus patient-centered practice requires attending to the patient’s unique experience of health and illness as an important part of practicing good medical care.

Dimensions of Health: Relevance to Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

Rex Kelly, the patient who was recovering from a previous myocardial infarction in the case study presented earlier in this chapter, saw himself as “no longer a healthy man.” In general, patients’ definitions of health undoubtedly influence their life and their care. Also, the providers’ definition of health, and their role in promoting health, inevitably permeates the care offered. Just as understanding the illness experience requires inquiry into feelings, ideas, effect on function, and expectations, so too understanding the unique perceptions and experience of health requires an exploration of health meanings and aspirations as well as the individual’s self-perceived health, susceptibility and seriousness of disease, ideas about health promotion, and the perceived benefits and barriers to health promotion and prevention.

To practice patient-centered care clinicians must think about the different conceptualizations of health as well as understand the patient’s understanding (way of defining) health for him- or herself. Historically there have been three conceptualizations of health: (1) health has been understood to mean the absence of disease, and this meaning holds true within the biomedical model of clinical practice today; (2) in 1940, the World Health Organization (WHO, 1983) defined health as “a state of complete mental, social and physical well-being, not merely the absence of disease and infirmity”; and (3) in 1986, the World Health Organization (WHO, 1986a) redefined health as “a resource for everyday life, not the objective of living,” a concept of health that emphasizes the individual’s aspirations, social and personal resources, and physical capacities. Thus, the notion of health has been shifted from its former abstract focus on physical, and then physical, mental, and social, status toward “an ecological understanding of the interaction between individuals and their social and physical environment” (de Leeuw, 1989; Hurowitz, 1993; Stachtchenko & Jenicek, 1990; McQueen & Jones, 2010). While the earlier definitions direct attention to objective factual data, the most recent definition directs attention to the subjective and intersubjective experience and enactment of health. How patients and practitioners think about and, therefore, experience health continues to evolve. In fact, all partners in health care have unique and often differing understandings of health and, in turn, they all have different understandings of health promotion and disease prevention to contribute to these aspects of health care.

It might be said that Rex Kelly sees his “not healthy” state as the losing end of an all-or-nothing continuum. Engaging Rex Kelly in considering his health, as his ability to pursue his own aspirations, could be described as health-promoting patient-centered care.

Health Promotion and Disease Prevention with the Individual Patient

Health promotion and disease prevention are important pillars in the “New Public Health Movement,” as described in the Ottawa Charter (Epp, 1986). Much of the energy directed toward these thrusts has been devoted to developing public policy, screening, and other methods, and to addressing related ethical issues (Hoffmaster, 1992; Doxiadis, 1987). The population-based approach to health promotion continues to be of high priority. Less attention has been paid to implementing ideas of health promotion and disease prevention at the level of the individual practitioner and patient. Frequently, this effort has been related to chronic disease management (Barlow et al. , 2000; Bodenheimer et al. , 2002; Farrell et al. , 2004; Lorig et al. , 2001b; McWilliam et al. , 1997, 1999; Squire & Hill, 2006; Steverink et al. , 2005; Wagner et al. , 2001). As primary health care reform proceeds, achieving new directions clearly hinges on the efforts of both individual practitioners and interprofessional teams. Viewing a primary health care practice as serving both individual patients and a population at risk (McWhinney & Freeman, 2009) necessitates both an individualized and a population health approach.

Undoubtedly, the original concept of health as the absence of disease continues to dominate medical practice, creating a focus on health as a product of the physician’s clinical work. The prevalence of chronic disease, multimorbidity, and the accompanying emphasis on self-care management also demand individualized attention to disease prevention as an ongoing part of medical care.

Additionally, however, as societal expectations for health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being (WHO, 1986a) increase, both solo and interprofessional practice also have increasingly attended to the individual’s and the community’s holistic potential for health. Health as a resource for everyday living – specifically, the ability to realize aspirations, satisfy needs, and respond positively to the environment (WHO, 1986b) – has come to the fore. Thus, primary health care teams have begun to consider and address the involvement of individuals and communities in health promotion. Attention to efforts to promote health and prevent disease has become an essential part of primary health care reform, complementing the population health approach. The patient-centered clinical method provides a clear framework for the practitioner to apply health promotion and disease prevention efforts, using the patient’s or the community’s world as the starting point.

The Patient’s Experience of Health and Illness

To understand the perspective of the patient, the practitioner needs to explore the patient’s experiential learning about health and illness, consequential personal knowledge and beliefs in relation to health and illness, and what each means to that person. The practitioner needs to discover the patient’s worldview of health and corresponding health-related values and priorities as one of many competing values in order to assess the patient’s commitment to its pursuit. These are inherently very individualistic, reflecting a diversity of personal values, beliefs, and aspirations that are experienced uniquely, contextualized by ethnicity (Papadopoulos et al. , 2003; Lai et al. , 2007), and the many other social determinants of health, and hence they require exploration with each patient. In fact, research suggests important considerations in promoting health. One consideration is a person’s perceived susceptibility to a particular health problem or to health problems generally. For example, perceived susceptibility has been found to be positively associated with screening and vaccination for hepatitis B virus among Vietnamese adults of lower socioeconomic and education levels (Ma et al. , 2007) and is an important dimension in Becker’s Health Belief Model (Janz & Becker, 1984). A second consideration is self-reported perceived health status, which has been correlated with a health-promoting lifestyle (Gillis, 1993).

A third element requiring exploration is health-valuing attitudes (or an image of being health-conscious), which may buffer socio-environmental risks (Reifman et al. , 2001). Health-valuing attitudes have been found to be strong motivators for health-promoting activity (Gillis, 1993; Reifman et al. , 2001; Wanek et al. , 1999). An individual’s perceptions of the benefits and barriers to health and a health-promoting lifestyle are important in determining whether or not a health-promoting strategy is adopted. Furthermore, individuals, who conceive health as the presence of wellness, rather than merely the absence of disease, have a significantly stronger engagement in health-promoting lifestyles (Gillis, 1993). Consistent with current notions of health as a process of mobilizing resources for everyday living, patients with chronic illness often experience health, and do much to create their own health (McWilliam et al. , 1996), with positive outcomes for themselves and the health care system (McWilliam et al. , 1999, 2004, 2007). Thus, it is important both to assess the patient’s own perception of experienced health and illness and to assess what health really means in daily life.

The Patient’s Potential for Health

The patient’s potential for health is determined by his or her exposure to broader determinants of health throughout the life course, age, sex, genetic potential for disease, socioeconomic status, and personal goals and values. However, perhaps the most challenging aspect of assessing a patient’s potential for health lies in identifying personal goals, values, and self-efficacy for health.

Personal aspirations and values are readily explored. However, self-efficacy – the power to produce one’s own desired ends – is not. Yet self-efficacy is also fundamental to the patient’s potential for health. Bandura (1986) suggests that self-efficacy behavior, which includes choice, effort, and persistence in activities related to desired goals or outcomes, is a function of (a) the individual’s self-perceptions of ability to perform a behavior and (b) the individual’s beliefs that the behavior in question will lead to the specific outcomes desired. Numerous studies document the positive correlation between these two factors and actual decision making and/or action regarding health behavior (Anderson et al. , 2001; Martinelli, 1999; Piazza et al. , 2001; Rimal, 2000; Shannon et al. , 1997; Sherwood & Jeffery, 2000). While research related to the influence of locus of control is contradictory, researchers have demonstrated that self-efficacy and health status are the most powerful predictors of a health-promoting lifestyle (Gillis, 1993; Stuifbergen et al. , 2000). Approaches that focus on increasing self-efficacy for health behaviors would improve health-promoting effort and quality of life (Burke et al. , 1999).

In summary, the more favorable the patient’s potential for health, particularly as it relates to self-efficacy and health status, the more appropriate is the practitioner’s role as facilitator of health enhancement.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have articulated the first component of the patient-centered clinical method, exploring health, disease, and the patient’s illness experience. Prior research has demonstrated how physicians have failed to acknowledge the patient’s personal and unique experiences of health and illness. Caring for patients in a way that promotes health and attends to the illness experience requires a broad definition of the goals of practice. The importance of exploring the dimensions of health (through thoughtful questions) and illness experience (particularly the four dimensions of the patient’s illness experience: feelings, ideas, function, and expectations [FIFE]) has been described and demonstrated through case examples. The bridge between health promotion and patient-centered care has been elucidated; a person’s perception of health and the practitioner’s openness to that person’s perceptions create opportunities for enhanced patient-centered healing.

The final two cases that follow bring to life the integrated approach, weaving among health, disease, and illness, leading to the clinician and the patient achieving a healing integrated understanding.

“I Don’t Want to Die!”: Case Illustrating Component 1

Judith Belle Brown, W Wayne Weston, and Moira Stewart

With shock and disbelief Hanna felt the lump in her breast. She felt it again and with mounting fear realized her cancer may have returned. Hanna had been diagnosed with localized cancer in her left breast 4 years ago. Treatment included lumpectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy. Axillary dissection showed no cancer in the axillary lymph nodes. She was given tamoxifen at that time, which she had taken faithfully. Since her surgery and treatments Hanna had been healthy with no symptoms. With vigor and determination she had resumed her active and busy life as a wife, mother, daughter, and worker.

Now, recognizing the need to seek medical advice immediately, Hanna contacted Dr Maskova, her surgeon, who performed a biopsy. A few days later, Hanna was called into the doctor’s office, at which time Dr Maskova broke the news that the biopsy results indicated a new cancer in the right breast. During the appointment, Hanna, a normally strong and independent woman, became distraught and wanted to leave immediately after her physical examination. Dr Maskova, surprised by Hanna’s response, suggested they meet again in a week to discuss the next steps. Hanna agreed.

Up until that fateful appointment with her surgeon Hanna had kept her fear of recurrence a secret. Hanna, age 48, had not wanted to alarm her 50-year-old husband, Arnold, who had been recently diagnosed with hypertension. A manager at a local food store, Arnold had been under extreme stress because of a possible strike action by the cashiers at the store. The last thing Hanna wanted to do was to add more stress to her already overburdened partner. Nor did Hanna wish to frighten her two children, Rachel (aged 14) and Jonah (aged 16). They had been very anxious and afraid of losing their mother when she was first diagnosed 4 years ago. Their worries had subsided and they were both currently excelling in their individual academic and social circles. Finally, Hanna wished to protect her 70-year-old mother from the fear and angst it would evoke to learn that her daughter might have cancer again. Her mother had endured enough losses in life; the loss of an infant son from sudden infant death syndrome and then the death of her husband 6 years ago of a myocardial infarction at age 64, just as he was about to retire. And now to possibly lose her daughter would be too much to bear. Hanna resolved to keep the diagnosis a secret – just a little longer.

Hence, in the intervening week until her next visit with her surgeon, Hanna searched the Internet. She also spoke with several friends regarding breast cancer recurrence and treatment. Since Hanna worked as a copywriter for a medical journal, she was comfortable with medical terminology and tests. She was also the type of patient who needed as much information as possible in order to make any decisions about her health. In addition, she had talked at length with her friend Adelle, also a breast cancer survivor. Unlike Hanna, Adelle had tried several different kinds of alternative therapies. Her cancer had not recurred in over 7 years and Hanna began to question if she should also have tried these alternative treatments. She had begun to question her faith in conventional treatments and, although normally quite decisive, she now felt confused and uncertain about how to proceed.

A week later Hanna returned to Dr Maskova’s office.

Dr Maskova: Hello Hanna – I am glad to see you back today. How are you doing?

Hanna: Hi Dr Maskova. It has been a hard week since I last saw you.

Dr Maskova: How so?

Hanna: Oh Doctor, I’m really scared, I wasn’t expecting anything like this. I haven’t slept in a week. I can’t eat, and my stomach is in knots …

Dr Maskova: It does sound like it’s been an awful week for you.

Hanna: Yes it has been awful. I have so many questions, and I am so confused. Will I have to stop working? I’m already finding it hard to work … I DON’T WANT TO DIE. I’m not ready to die; my children are just teenagers – they still need me.

Dr Maskova: There is a lot going on Hanna – a lot to consider. Tell me more about what is happening.

Hanna: Yes, and I have been on the Internet and I’ve been talking to friends. I need to know if I should have done things differently. Should I have restricted fat from my diet? Should I have taken shark’s cartilage or Essiac? My friend has done these things and her breast cancer has not come back in over 7 years. Could it be that they prevented a recurrence for Adelle? Why did I get a new cancer? Isn’t that very rare? What am I doing wrong?

Dr Maskova: (Feeling overwhelmed by the multitude and rapidity of his patient’s concerns, the doctor decides to try to gain a better understanding of Hanna’s life and context.) You’re asking a lot of important questions, Hanna. I feel I need more information before I can answer them properly. Can you tell me, Hanna, what’s happening at home? – with you and the family?

Hanna explained that she had not told her family because her husband was under tremendous strain at work and had high blood pressure. She described her children’s fear that they would lose their mother. Most important, Hanna did not want to upset her mother; she had already had enough losses in one lifetime. Hanna perceived that the well-being of all these people was basically on her shoulders and she clearly felt overwhelmed.

Hanna’s confusion and anxiety dissipated as Dr Maskova took time to listen to her story. He was honest, caring, and understanding. Dr Maskova validated her concerns and worries about the effect of her diagnosis on her family and explored ways to address how best to involve them. He listened to her growing doubts about conventional treatments and allayed her fears that she could have, or should have, done more to stop her cancer from recurring. With respect, he explored her inquiries about alternative therapies and discussed how they could examine the efficacy of such treatments together. The doctor also provided Hanna with sufficient information at the appropriate moments and provided guidance in making informed decisions. Dr Maskova supported Hanna’s decision to seek information about alternative medicine, offered advice on authoritative websites, and provided contact information for a local support group. Dr Maskova made it clear to Hanna that she would be given opportunities to choose between treatment options and be involved as much as she wanted in all the decisions throughout the course of her treatment.

At the conclusion of the consultation, Hanna felt more informed, more certain, more in control, and less overwhelmed. The doctor had achieved this by exploring Hanna’s feelings and expectations and by building on his relationship with Hanna, resisting his temptation to take over and provide all the answers. Dr Maskova indicated that he would be there for her through her treatment and recovery.

Hanna’s interactions with her surgeon consequently became pivotal in regaining control. She needed information from him that would assist her in the multiple treatment decisions before her. She needed a surgeon who would listen to and respect her concerns and wishes. For Hanna, a relationship with her surgeon, built on honesty and reciprocity, was paramount. Hanna also needed a surgeon who expressed an interest in both her and her family – taking into consideration their needs and anxieties. By developing a trusting and respectful relationship with her surgeon, Hanna was able to regain some semblance of control over the chaos she was experiencing. Dr Maskova did not dismiss Hanna’s questions or negate her worries; rather, he took the time necessary to explore her fears and that in itself helped to alleviate her concerns.

As Hanna progressed from the shattering realization of the recurrence of cancer to the treatment phase, she and her physician engaged in a process of establishing a mutual understanding of what should and would transpire. At each point in her treatment they discussed the current situation, her various options and what would be the most appropriate plan. Hanna, by choice, became an active and informed partner in her care, thereby regaining the courage to live with cancer.

“I Should Write a Letter to the Editor!”: Case Illustrating Component 1

Carol L McWilliam

Mrs Samm was an 80-year-old widow with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypertension. Both the physiological incapacitation and the accompanying need for oxygen by nasal cannula severely limited her mobility, leaving her largely confined to her eleventh-floor apartment, where she lived alone. Mrs Samm managed from day to day with the assistance of her only daughter, 60-year-old Gloria, who lived on a farm 40 minutes outside of town but dutifully visited every Wednesday afternoon to clean her mother’s apartment, to grocery shop, to assist with managing the household finances, and to organize meals, which she froze in individual meals for easy preparation by microwave. Additionally, Gloria visited every Sunday afternoon along with her farmer husband. Both were reluctantly pursuing this family routine despite the 24-hours-a-day, 7-days-a-week demands that the farm placed on them as an aging, childless, self-sustaining couple. Every week they listened to Mrs Samm’s incessant complaining about everything from the weather to her lot in life.

Dr Aronson, Mrs Samm’s aging family physician, had cared for her for many years, supporting her through a life-threatening diagnosis of meningitis that Gloria had contracted as a teenager, through her husband’s 2-year battle with terminal lung cancer, and through her own struggle to quit smoking at the age of 75, as her own chronic obstructive pulmonary disease worsened. Now, Dr Aronson made a house visit to Mrs Samm once a month to monitor her condition and treatment.

In the past, Mrs Samm had managed to amuse herself by watching television, reading, and talking on the telephone. However, Mrs Samm’s condition had begun to deteriorate in recent months. Increased difficultly breathing, loss of appetite, and anxiety related to a fear of developing lung cancer had begun to take its toll. Mrs Samm had become preoccupied with the fear of having to go to a nursing home, or worse, the possibility of death. As her preoccupation intensified, Mrs Samm had begun to make regular visits to the hospital emergency room, seeking urgent medical attention for chronic symptoms that were clearly being adequately managed at home under her family physician’s care. In response, emergency department physicians were urging Dr Aronson to consider admitting Mrs Samm to a nursing home.

Familiar with Mrs Samm’s larger life context and her personal goal of avoiding admission to a nursing home, Dr Aronson decided to explore the broader notions of health with Mrs Samm. He knew from his routinely provided care that her condition had not really deteriorated. Dr Aronson needed to know more about how Mrs Samm viewed health, and what personal resources she might have to optimize her health, despite her chronic illness. Also, he needed to learn what her commitment to the pursuit of optimizing her health, despite the chronic illness, might be. He recognized that there might be broader determinants of health entering into Mrs Samm’s current inability to maintain the level of wellness and quality of life that she had managed to have for the last several years. He decided to see if he might promote health by engaging her as a partner in its enhancement.

Accordingly, during his next visit, the following conversation transpired.

Dr Aronson: While I see no change in your physical condition over the past year, you seem to be experiencing more illness in recent months. Can you tell me about your experience of health right now?

Mrs Samm: I’ve lost my confidence. I’m afraid I will end up in a nursing home. Now, every time I feel a little down, I think I’ve just got to get help! I go to the hospital’s emergency department and they check me out and just send me home. That makes me angry and upset, and I begin to worry even more and get very frightened that I will end up in a nursing home. It’s a vicious circle, and I don’t know what to do, don’t know what will happen, don’t know where I’ll end up.

Dr Aronson: You are afraid because you don’t know what to do, don’t know what will happen, and don’t know where you’ll end up.

Mrs Samm: Yes, that’s it.

Dr Aronson: So it’s fear of the unknown, isn’t it.

Mrs Samm: Yes, that’s it. And it’s affecting my health.

Dr Aronson: So is there anything that can be done about this fear of the unknown in order to help your health?

Mrs Samm: I don’t know, I just want to be able to do the things I want to do.

Dr Aronson: Yes. And what might some of those things be?

Mrs Samm: I don’t know. I guess I’ll have to think about it.

Following this lead, Dr Aronson agreed and suggested he would come again to monitor her condition next week. At the next visit, following his routine examination, Dr Aronson resumed his effort to engage Mrs Samm in health enhancement.

Dr Aronson: So have you come up with a list of things you’d like to do?

Mrs Samm: Well, for one thing, I’d like to able to be more actively involved in the community like I used to be, but that’s out with this bad breathing problem!

Dr Aronson: Maybe, maybe not. I wonder if there is anything in particular you think you might like to do?

Mrs Samm: Well, I’d sure like to do something about the mess City Hall has made of our water bills! The latest billings are outrageous, and it’s all because they’ve increased the rates to offset the cost of new housing developments!

Dr.Aronson: I wonder what you might be able to do about it from here?

Mrs Samm: Well, I should write a letter to the editor. Someone should tell them what this means to people like me on a fixed income!

Dr Aronson: Yes, that’s a great idea. I think you should do that.

Dr Aronson made a commitment to check up on Mrs Samm in 2 weeks, and followed up accordingly.

Dr Aronson: How is your health today, Mrs Samm?

Mrs Samm: Well, I’ll tell you, my blood pressure must be back to normal because I did write that letter to the editor, and I’ve since had telephone calls from many seniors who happen to agree with me, and from my city council member, who has agreed to address it at the next council meeting. I’m glad you helped me to get onto this. When the counselor called, I also told him what I thought he should do about the problem of vandalism in our parks, and I’ve written a letter to the editor about that too!

Dr Aronson: Sounds like you’ve found a new niche in the world.

Mrs Samm: (Chuckling) Well, perhaps I have. I certainly am going to keep on to these problems. Somebody has to!

Dr Aronson agreed, and proceeded to check Mrs Samm’s vital signs, review her medication adherence, and make his usual assessment. Dr Aronson observed that Mrs Samm had not been making her usual trips to the emergency department and he and Mrs Samm agreed that she was well enough for him to go back to the routine of visiting once a month.

This case illustrates how patient-centered practice can facilitate the promotion of health as a resource for everyday living. Dr Aronson sought a broader understanding of Mrs Samm, and her experience of health, illness, and disease. He determined that health to her meant being able to do the things she wanted to do. He helped her explore her commitment to and options for achieving her notion of health. He also facilitated her determination of what and how much she might do to experience health more positively, despite her debilitating chronic medical problems, and within the broader parameters of her larger life context. He used a patient-centered approach and built on the continuity of his relationship with her to enable her to use her full resources for everyday living, thereby optimizing her ability to realize her aspirations, giving her a renewed sense of purpose in life, to satisfy her needs for social cohesion within her community, and to respond positively to the environment, despite her chronic medical problems.