CHAPTER FOUR

HOW TO TASTE

BOURBON

Bourbon is not meant to be intimidating. But there are a few tasting methods you can apply to help you pick up aromas and flavor nuances.

When I’m assessing bourbon for competition or critiquing for a magazine, I analyze the color. The darker it is, the older the whiskey and the higher the proof; with each year in the barrel, the liquid gets a little darker. And the more water added to lower the alcohol by volume or proof, the more diluted it is and the paler in color. I score the whiskey’s color based on its vibrancy, richness, and occasional hues discovered in the swirl.

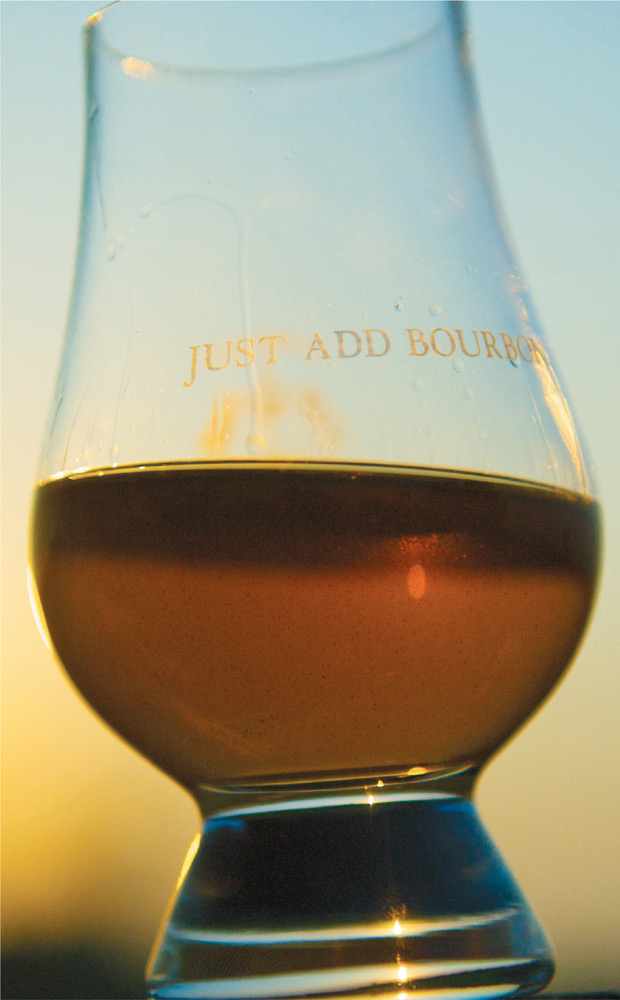

Bourbon has a way of glistening in the sunlight. Due to the use of a new charred oak barrel every time, bourbon yields incredible colors when held up against the sunset or sunrise. These are popular Glencairn glasses that are made for sipping whiskey.

After scoring its color, I’ll swirl the bourbon and analyze the legs. In wine, the legs are sometimes referred to as wine tears as they trickle down the glass and are shaped like tears. Legs or tears are the hallmark of the Gibbs–Marangoni effect, in which evaporation causes fluid surface tension. In wine, legs point toward high sugar content, but in bourbon, they show character and complexity, offering a slight look into what oils survived distillation and filtration. Longtime Wild Turkey master distiller Jimmy Russell observes that the longer a bourbon’s legs, the more robust its flavors. I’ve also found the closer together the legs are, the more depth and character there is from aroma to the finish. With that said, I’ve enjoyed bourbons with hardly any legs at all, so analyzing the legs is more of an observation than a scoring method.

Once I’ve studied the bourbon legs, I stick my nose in the glass, open my mouth, and smell. By opening your mouth, you release the tension on your olfactory glands. Let’s face it: bourbon can bring some heat to the nose, especially when the spirit is more than 100 proof. With an open mouth, your body has two portals from which to breathe oxygen, and your nose doesn’t get one heavy dose of alcohol fumes. This method also lets you really assess the aroma.

When you give your nose a chance, you might find these aromas in one of your pours.

Then, I taste, feeling the spirit against my tongue and marking its particular flavor notes. Did the aromas match the notes on the palate? Or did the alcohol burn itself through the tongue? The alcohol burn is not preferred; you want to enjoy the taste of whiskey, not feel an acidic nightmare upon your lips. If you’re not accustomed to drinking spirits neat—meaning without ice or water—I recommend a splash of water or an ice cube so your tongue doesn’t burn too badly. Tasting whiskey should be an enjoyable experience, not a painful one. But there’s a difference between alcohol burn and spice, a character found in most bourbons that contain rye as a secondary grain.

Bourbon’s alcohol burn happens when the spirit penetrates down the middle of the tongue like a nine-volt battery and stings all the way down. With spice, the tongue feels a slight tickle in much the same way a hot pepper would. Once you’re accustomed to the spirit’s texture on the tongue and understand the difference between burn and spice, you can analyze the subtleties in bourbon.

Allspice

Almonds

Anise

Anise seed

Apple, baked

Apple, juice

Apple, sliced

Apricot

Apricot, dried

Baked pies

Bananas

Basil

Bay leaf

Bell pepper

Black pepper

Blackberry

Bleach

Blueberry

Brown sugar

Butterscotch

Campfire

Caramel

Caramel-scented candle

Caraway

Cardamom

Cedar chest

Celery seed

Cherry

Chocolate

Chocolate caramels

Cigar box

Cilantro

Cinnamon

Citrus, general

Citrus, lemon

Citrus, lime

Citrus, orange

Clove

Cocoa

Coconut

Coffee

Coriander

Corn

Cornmeal

Crème brûlée

Crushed grapes

Cumin

Dill seed

Dill weed

Eucalyptus

Fennel

Fenugreek

Floral

Fresh-baked biscuits

Fresh-baked bread, wheat or rye

Geranium

Ginger

Green pepper

Heated caramel syrup

Herbs

Honey

Lavender

Leather

Lemon zest

Licorice

Lilac

Mace

Malt-O-Meal

Maple syrup

Marjoram

Marijuana (yes, really)

Mint

Mustard

Nutmeg

Oak

Oatmeal

Orange

Orange juice

Oregano, Mediterranean

Oregano, Mexican

Pan-melted caramel

Parsley

Pear

Pecans

Pepper

Peppermint

Petrol

Pine

Pineapple

Pink pepper

Plum

Poppy

Praline

Pumpkin pie

Raisins

Raspberry

Rose petals

Rosemary

Rye

Rye meal

Saffron

Sage

Sassafras

Savory

Sesame

Sweaty gym socks

Tarragon

Tea

Thyme

Toasted nuts

Tobacco

Toffee

Turmeric

Turpentine

Vanilla

Vanilla beans

Vanilla extract

Vanilla ice cream

Vanilla icing

Vanilla pudding

Varnish

Walnut

Wheat

Wheat meal

White pepper

If you really want to take your bourbon nose to the next level, go to your local natural grocery store and buy scents to smell and train your nose.

Bourbon’s flavor notes tend to skew toward age and mashbill. Or rather, these are the most common denominators that we as tasters can verify and compare in the tastings. Younger bourbons will have more grain notes, for example; high-rye bourbons, such as Four Roses, will typically pack an easy-to-identify cinnamon note. With that said, there is one note you should always find in bourbon if it’s at least two years old: caramel. If you cannot taste caramel in a straight bourbon, it’s flawed. The charred barrel imparts caramel and vanilla in every bourbon, even the bad ones.

As for the nuances you find in bourbon, this is where it gets fun. What you taste will be completely different than what your friend tastes. In professional whiskey circles, we all tend to pick up the same obvious notes, such as grain, caramel, cinnamon, nutmeg, and vanilla, but our identification of more complex notes varies widely. Legendary bartender Joy Perrine, author of The Kentucky Bourbon Cocktail Book, finds bananas in Old Forester. Perrine used to live in the Caribbean, eating tropical fruits straight from the source; her palate and perception of banana are much different than mine. My colleague Mark Gillespie frequently picks up campfire smoke in older bourbons that I just describe as smoky. Why campfire smoke specifically? Well, Mark camped out a lot as a kid and effectively discerns the types of smoke he’s smelled. As for me, I grew up in agriculture, raising hogs and horses. I’ll detail a grainy note that reminds me of the sweet feed I used to feed my horses, and I’ll reference to the Jolly Ranchers I munched on as a kid.

In other words, as tasters, we have no recourse but to trust our instincts. Your taste buds and memory are intertwined, and bourbon will tap into your taste bud memories. If you taste biscuits and gravy, by all means, make a note of it, but challenge yourself to further define the note. Is it biscuits and pork gravy loaded with pepper? Or biscuits and a lighter gravy lacking salt? When you taste something and actually think about it, you’ll be amazed how easily the mind creates tasting notes.

Once you’ve completed this portion of the taste, it’s time to assess the finish. The finish is how it feels on the way down. If you don’t feel the burn as the whiskey travels down the hatch, this represents a smooth finish. Sometimes, the finish offers subtle finish notes, when the whiskey actually has traveled down the esophagus and your tongue picks up final flavors; often, these are the same notes that are the most prominent to begin with. The longer these finish notes last on the tongue, the better.