tu casa

(My house is your house)

I swear to myself I will never call him again, even if I have to sprint all the way across the Brooklyn Bridge into Manhattan in the biting cold.

And I’m not going to, not this time, not after his sudden outburst that last time on the way to the airport.

He had been moody and fractious, his face set into a scowl that was most uncharacteristic and most unbecoming. Even his eyes snarled. The traffic, by contrast, was everybody’s best friend that day: chilled, easy-going yet attentive, letting you cut in, allowing you to rant and rave or swerve and brake as capriciously as you wanted, always listening and never judging.

But I wasn’t Emilio’s best friend; I was his passenger. Our personal history aside, the fact was that he’d been contracted to take me to JFK in his Town Car. There was a certain level of decorum expected in such a transaction. This wasn’t some clunky yellow taxi I’d hailed at the corner of 75th and Lex with a dour-eyed driver drenched in eau de fastfood at the wheel exploding on the phone to a compatriot in his head-bobbing machine gun staccato language.

Clearly, Emilio was having a bad day. The air in his car, usually redolent of leather and spice, seethed with some kind of resentment. Against what, it was hard to tell. He wasn’t exactly chatty throughout the ride.

So baby talk to me

Like lovers do

It wasn’t about school, he grumbled when I asked. Neither was it about work nor anything to do with family. So what was eating Gilbert Grape, I wondered. It couldn’t possibly be me, could it? What did I do? And why should it matter to Emilio?

Trapped in the strained silence of the car, I went over in my head the events leading up to Emilio arriving to take me to the airport. He had class, he’d said, after that he was heading over to pick me up, and I should expect him around eight-fifteen, eight-thirty this evening. I’d texted him back, asking him to let me know when he was nearby. I’d gone to The Mark, a few blocks away, for farewell cocktails with Orlando. One drink, I’d told Orlando sternly. He had three.

“Where are you?” Emilio had demanded on the phone. “Are you out again?” His tone—midway between annoyed and possessive—took me by surprise. But maybe I was reading too much into the situation.

“I’m having drinks at The Mark with a friend,” I’d replied. “It’s not far from the apartment. It’ll take me ten minutes to walk back home. I’m all packed anyway.”

“Yeah, well, I’ll be there soon. I don’t know what the traffic is gonna be like so we should leave right away.”

So no boom-boom before the fly-fly? A departure, admittedly, from our customary pre-departure ritual. Which was a relief, to be honest.

Phew.

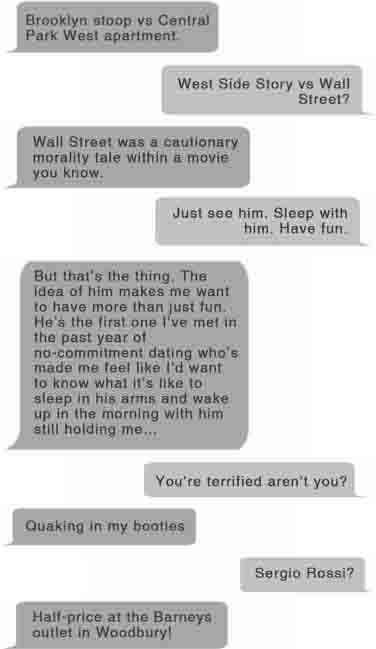

Call me old-fashioned, but I couldn’t quite picture myself impaled on Emilio’s dick ever again after kissing Carlos the other night. And that’s all we did, kiss. But it was the kind of kiss that was wondrous and sweet and greedy and sad all at once, that stilled the stars yet made the sky spin. The kind of kiss that spoke of infinite possibilities, at least until dawn broke, and infinite sorrows, once the day edged out the night. Carlos entered his number on my phone and made me promise to call him. Then we got into separate cabs and I never called him.

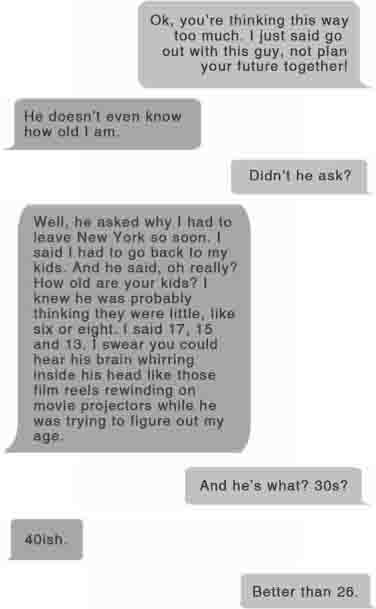

I held on to his phone number for twenty-four hours, and then I deleted it. An act of unfathomable stupidity, perhaps, or abysmal cowardice, but for now I wasn’t going to bother to dissect the matter too deeply. Maybe in the end it was merely an act of practicality. Whatever. I was leaving in two days. I didn’t know his last name; he didn’t know mine. I wasn’t going to look for him, and I didn’t want to be found. Not now, at least.

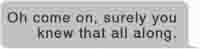

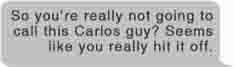

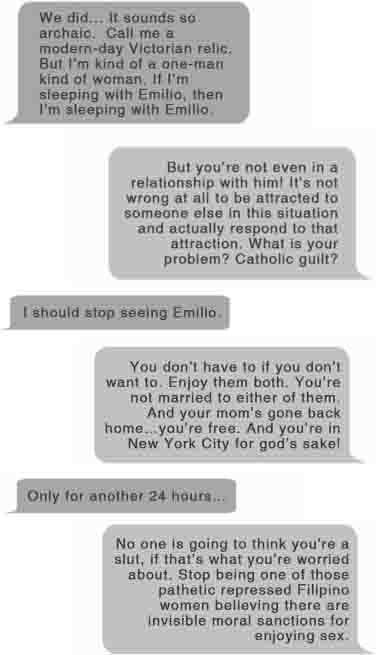

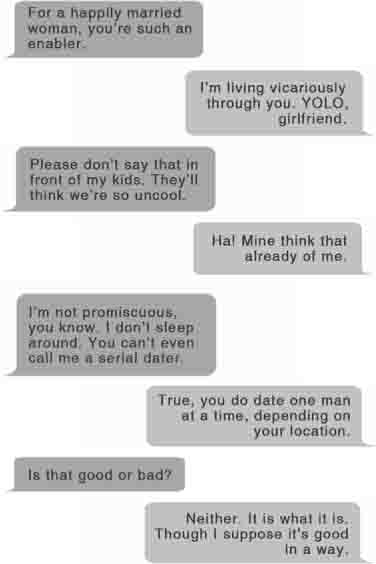

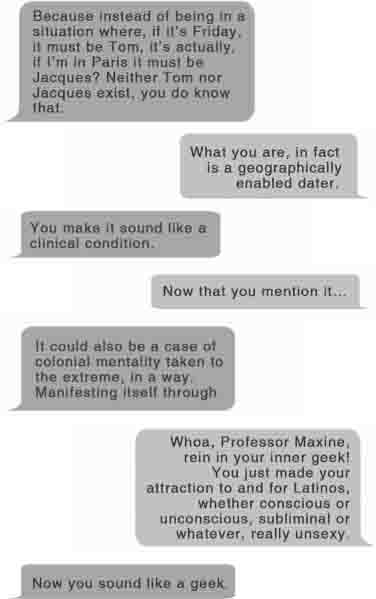

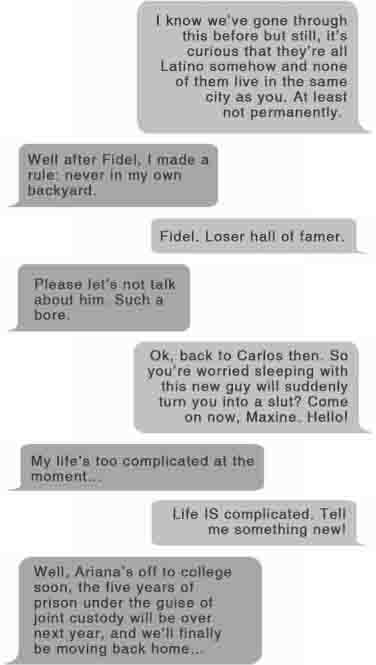

Corinna couldn’t understand why, and remained convinced, while we were chatting on WhatsApp, that my logic was downright demented.

Of course I knew that all along. As callous as it sounded, I was finding it increasingly ridiculous that my amorous memories of New York in the past year were all tied to Emilio. Literally tied to him, even, if one were to consider the time he bound my hands behind my back with rope … Never mind. Being with him was fun and exciting, and to a degree, subversive, but all that was beginning to seem a bit banal. How did an intermittent sexual relationship dictated by location between a woman nearing fifty and a boy almost half her age, a boy from a completely different background on all levels, economic, intellectual, social, cultural, a boy so sweet and decent and well-mannered, a boy still making himself into a man—how did such a relationship suddenly become a safe thing?

But meeting Carlos was unsettling; kissing him even more so. I wanted nothing more than to see him again. And talk. And kiss. And laugh. And walk into the moonlight with, night after night. Instead, I deleted his number. Idiot. But it wasn’t out of any distorted sense of fidelity to Emilio, believe me, even if he was the only one I was sleeping with whenever I was in New York. It was more out of a personal sense of ethics, I suppose. True, I wasn’t interested in a committed relationship at the moment, but even casual relationships were not exempt from a certain code of honor. I just couldn’t sleep with one man and kiss another. At least not in the same city. It wasn’t me.

The one person I should have called was Emilio, to cancel the car to the airport. I could have told him I had changed my flight or that I was going to Boston for the day or someone else was driving me to JFK. But I didn’t. Partly because I would have to make excuses for cancelling, which I didn’t want to do, and partly because I wanted to see whether I’d take one look at him and bite my lip till I felt the sting of regret, wishing I’d called Carlos instead.

And now, cruising past LaGuardia on our way to JFK, slouched back in our seats in grim complicity, I’d given up trying to figure out what was bugging Emilio and wondered how much I should tip him this time. I didn’t expect any poignant goodbyes outside of Terminal Four like the last time, when he kissed me so sweetly and lingeringly that when I finally opened the door and stepped out into the curb, the TSA agent took one look at me, shook her head and said, smiling, “He didn’t want to let you go, huh?” No, there would be no kiss this time.

“So when are you back?” Emilio asked, shattering our little cocoon of gloom.

“Me? I’m not sure. I might be back in the fall for a conference with my client. You met her—Kate. Or I might come early next year to check out colleges with my daughter. Who knows?”

“You’re so lucky things come so easy for you.” He shook his head, as if to lament his own checkered fortune.

“Easy?”

“Yeah. You got it made, sabes que te digo?”

“Listen,” I said, keeping my voice even lest he think I was being shrill and defensive, “I work really hard to live the kind of life my kids and I live. I am lucky, sure. But I make my luck.”

“Yeah, maybe you do. But you come from money—”

I cut him off. “You don’t know what you’re saying—”

“It’s pretty obvious you have enough to be comfortable. Plus, you’ve already got all the advantages. Things happen for you in a way that they never do for me.”

“But you’re making something of your life, you’re back in school, you don’t want to be a limo driver forever … you’re making things happen for yourself, too.”

“The system’s stacked against people like me. No matter how high I climb, the system always drags me down somehow.”

We were speaking in ellipses. “In what way?”

“It’s just stuff. You wouldn’t understand. You don’t have to fight the way I have to for everything.”

It was beginning to sound like one of those conversations on a loop that I used to have with my kids in the early years of my separation, endlessly replayed and never resolved.

“We all have our battles to fight,” I said patiently. He’d obviously never been involved in a divorce and custody battle in a country where the legal system was dismally twisted and inept. “It’s how you deal with what life throws at you, you know?”

He was still shaking his head, resigned. “You’re not from my world, you wouldn’t know. I’m stuck. I’ll never get out. And you, well, you’ll travel when you want and where you want, shop with your mom or whatever, eat in all these fancy restaurants and party and have cocktails and not worry about anything. No sabes la suerte que tienes.”

“But—”

“You know what’s funny?” He laughed bitterly. “I came here from the DR when I was six years old ‘cause this was the land of opportunity. America, que ilusión, my parents always said. But what opportunities did I have? Work in a dead-end job or be in a gang, get shot or rot in jail.”

Just then, JFK loomed in front of us and I knew the discussion was over without ever having gone anywhere. Now I had to overtip him because I felt awful about the apparently insurmountable class divide between us.

“Look,” I said as he loaded my suitcases onto the trolley, “don’t be so hard on yourself. You’re just having a bad day. It happens.”

“I can’t take this, it’s too much,” he frowned when he counted the bills I’d pressed into his hand.

I waved him away. “No, please, it’s fine. I’m proud of you, really. You’re working really hard—”

Suddenly, he bent down and planted his lips on mine. And just as suddenly, he stopped and straightened up. “Gracias,” he said, a hint of a smile finally appearing on his face. “I really wanted to see you today, you know. I really did. Because—I was having a good day, in fact, and on my way to you …”

“What happened then?”

“I don’t know. You were out having drinks.” He shrugged.

“So?”

“Like I said, we’re from different worlds.”

Maybe it was for the best that our worlds never intersected again.

I’ve been to Williamsburg before, but this is a whole other world.

There are no hipster coffee bars with organic white chocolate biscotti displayed under glass bell jars lining the streets. There are no modern high-rise condos clad in blinding mirrored glass or sedate brownstones framed by trees. Instead, there are anonymous apartment blocks painted in the weary white of the working classes, stuff crammed into shops crammed into streets, pavements overflowing with people, little triangles of colored bunting strung on wires dancing from pole to pole, the air pungent with fried plantains, heaving with testosterone and tight jeans, and Spanish spoken everywhere—a confusing kind of Spanish, rapid yet languid, slithering with slurred consonants and disappearing “s”s. It’s like every day is a quinceañera celebration or a Puerto Rican parade, passion and hope sizzling and flailing.

This is Emilio’s world, and I don’t belong here.

I deserve to be shot in the head for coming here. No, I deserve to be hung from the ceiling like a gaudy, frilly piñata first and hit at from all directions until I rip and tear and finally understand that calling Emilio again after resolving months ago never to do so is the height of reckless stupidity. Then I deserve to be shot in the head.

But boy, what a trip.

Hey babe, take a walk on the wild side

It’s the end of September, and I’m back in New York with Kate to attend a conference on ethical beauty. It’s a key moment for her, and for us as an upstart brand in the booming organic beauty market: she’s been asked to give a talk on Ethics and Beauty in Emerging Economies. I know what you’re thinking: snooze fest. Wrong. It’s actually an interesting topic, or at least it has to be, since I’m writing her speech. The idea is to make people share our fascination for the traditional beauty rituals rural African communities have relied on over the centuries, using their wisdom and understanding of the power of plants to cleanse, nourish, protect, and firm. The same rituals, actually, that inspired the creation of Eairth Essentials.

But it’s not just about communicating the richness of Africa, Kate and I agree. We also have to make people aware of the inherent ironies in the industry. “For centuries,” she will explain when she takes her turn at the podium, “bushmen and the women of Southern Africa have long been aware of the amazing properties of the various plants around them. Of course they couldn’t expound it in the terms we use today; they wouldn’t have been able to say that the oil of the Kalahari melon, for instance, was high in essential fatty acids—linoleic, oleic, and palmitic—which helped to improve and maintain the integrity of the cell walls. Modern scientific research has established that. But they sure knew that there was in something in the oil that nourished the skin and kept it supple.”

“But Kate,” I say as we are going over the draft, “someone might say, ‘hey, have you seen the face of a Kalahari bushman?’”

She laughs. “I am fervently hoping no one will point that out! In our defense, I will say, well, touch the face of one such bushman and see for yourself. It may be lined, but I’m pretty damn sure it’s smooth!”

The speech must have worked; there is a lot of attention from the press, as well as a couple of venture capitalists, keen suitors who lure us with invitations to lavish dinners we are too starry-eyed and weak-willed to refuse. So when I jokingly say to Kate, “judging from the reaction of those present, I think I can increase my retainer from this month,” she nods and smiles and says, dead serious, “perhaps you should consider having some equity as well.”

After five days of back-to-back meetings and talks and store visits and rushed cocktails with friends, then dinners with potential investors, I have practically sprained my neck craning it at every opportunity looking—subconsciously, of course—for Carlos, above the crush of bodies in a West Village wine bar, beyond the sea of faces in a restaurant in the Meatpacking district, past the champagne-swilling crowd at a Chelsea art gallery, amidst the phalanx of pedestrians along Madison Avenue. But I never find him. I don’t even know where to begin looking for him.

So I go to Brooklyn instead, looking for Emilio. Because he invited me.

He seems genuinely happy to hear from me. School’s going great, he says. He is so chuffed; he finished his freshman year with a 3.5 GPA, an impressive grade by any standard. Otherwise, work is, well, work is work. In other words, life is good, everything’s fine.

Maybe he thinks I’ve shrugged off the class distinctions that separated us and forgotten about his ill-tempered outburst the last time we saw each other. Maybe he’s forgotten himself how cranky he’d been. Maybe he’s simply delighted I called and even more delighted at the prospect of getting some action. And maybe, just maybe, this would be one other hoop he’s hoping I won’t mind leaping through: coming over to the ‘hood and meeting the family.

Of course, when he says, “Meet me in the afternoon, I have to take care of the music at my cousin’s party,” I assume it’s the quinceañera effect:

Afternoon party = teens

Emilio = DJ, two hours, tops

It is, in fact, a kiddie party and family reunion to celebrate the birthday of his cousin’s daughter, who is turning a year old amid a riot of balloons and frills and confetti and gaudy pink satin. To my horror, the entire Dominican Republic of Brooklyn got the memo and all its citizens are present and accounted for that afternoon in that multipurpose function room drenched in fluorescent lighting in the basement of an apartment building that is indistinguishable from all the other apartment buildings on the block. Babies, children, teenagers, brothers, sisters, cousins, aunts, uncles, grandfathers and grandmothers, they are all there, crying, running around, laughing, dancing, drinking, gossiping, and looking at the gringa who looks a little bit asiática, who’s come to see Emilio, of course it has to be Emilio, he’s the man, the man with the music, the man with the merengue moves, the man with the twinkling eyes and the killer smile, the man with the girl, always the man with the girl.

Emilio holds court in the corner that naturally becomes the nucleus of the room because he’s the man with the music, the man who makes the magic happen, with the kick-ass macho speakers and the professional sound deck and the playlist that gets everyone in the mood to sway their hips and shimmy, even the kids bounce up and down with the beat, feeling the throb of the Caribbean in their veins, even if they’ve never been to the country that their parents fled, and look, here’s the abuela, stooped but still regal, skin mottled with liver spots but fair, so white, she is almost blue, de sangre pura, never worked a day in her life until she came to America.

I am his consort, mesmerized by the pageant before me, seduced by the rhythms seeping into my skin, charmed by the curiosity with which I am regarded, and the warmth with which I am approached, and awed, simply awed by Emilio so in his element, so alive, so much the king of his realm. I think of Carlos, who was shyer and less cocky, but commanding in his own way. Is he really lost to me now, or should I have tried harder to find him? But how? It’s pointless to even think about Carlos with everyone milling around us. Everyone comes to say hello, and Emilio just says, “This is Maxine,” and they smile, and the men shake my hand while the women kiss me on the cheek, ask me if I want something to drink or eat, and I wonder what they think our relationship is, is it obvious I’m not from here, is it obvious I’m much older, is it obvious that we’re fucking each other?

I sit beside him as he spins his magic, part dutiful girlfriend, part gangster moll, part Asian courtesan, getting up to get him a beer from the kitchen every now and then, chatting with the tia who is definitely my age but doesn’t know it, telling his sister her two-year-old baby with the blonde ringlets is adorable, shyly declining his invitation to dance because en serio how can I when everyone is watching, and I’ll look like an idiot, so stiff and so sober and so self-conscious because I don’t have that tropical heat in my blood, at least not yet, not at six in the afternoon. I don’t have that duende that will make me want to press my hips against his and place my thighs in between his, moving in step with him and throwing my head back like it’s the most natural thing in the world to do, to make love with each other through dance. So instead he squeezes my thigh and whispers that maybe we could sneak out and fuck in the bathroom a little later because he really wants me and has to keep it all under control because oye, he can feel his dick getting hard and he just has to behave because they are all here, everyone he knows, everyone who is somehow related to him by blood or by law.

Two hours, tops, turn into four hours, more for Emilio, who’s been manning the music since three and it’s now nine at night and the birthday girl is crabby, the children are shattered, the adults want to rush home to watch what’s left of their telenovelas, and the teenagers and the twenty-somethings have their own parties to run to, with real liquor and weed and probably more, not just birthday party soda and beer that they can’t touch anyway because it’s reserved for Emilio.

I help his aunt, the grandmother of the birthday girl, clean up the room and wrap up what’s left of the massive mermaid cake, while he and his brother, who looks a lot like him and has the same beautiful manners, unplug the speakers and load all the equipment into the car. There’s a party going on somewhere and all the kids are going to be there, but Emilio suggests going to his house first to drop off the speakers. We stop by a store on the way because we apparently need more ice and beer, plus he is out of condoms. In the store, he looks around like he is casing the joint and we are Cougar Bonnie and Under-aged Clyde planning a robbery, but when he is certain the coast is clear, he kisses me by the drinks cooler, tasting of beer, bacon, and cigarettes, and I can see the reflection of him kissing me in the security mirrors above us and feel like a high school junior playing hooky. A minute later, I feel like a sugar mommy when I have to pay for everything because Emilio left his wallet at home. He does offer to pay me back, which is sweet, and of course I refuse.

His apartment building is old and tired and the elevators screech with despair from floor to floor. He warns me that his parents are home and I keep saying, “are you sure it’s okay, we can go somewhere else,” but he keeps saying, “don’t worry, it’s okay, relax, venga, no te preocupes I want them to meet you.” I leave it at that. I don’t want to know why he wants them to meet me, the girl, no, the woman, the fortysomething-year-old with grown kids who lives in South Africa—he knows, he remembers, because he told his brother and his sister and his cousins and his aunts at the party that I was from there, but that I was actually from the Philippines and was part-Spanish, that he met my mom, she was the Spanish one, she was really cool and she smoked like crazy, that my dad wasn’t doing so well in the memory department, that I also spoke Spanish, go ahead and talk in Spanish, see, he said, I told you—the woman who comes from a different world from his, sometimes it feels like a different galaxy even, but whom he likes being with and obviously likes fucking.

I don’t know what it means, but I know it’s a big deal though, me coming to his ‘hood, out in the open, not making out in his car or sneaking off to that dingy motel, but coming to the fiesta, meeting the entire barrio, the Dominican Republic of Brooklyn, and now meeting his parents.

I have no idea what to expect, but nothing could have prepared me for the scene that is straight out of a Mexican telenovela. His mother, pale and plump and slumped on a chair against a metal-frame table that is dining table and desk; his father portly and patrician-looking, hunched on the sofa that is covered in plastic, watching what else but a telenovela, clad in a wife-beater and boxers. As soon as we walk in, voices are raised and accusations are hurled, a drama within a sitcom, Brothers and Sisters meets Modern Family, and they scream at each other in Spanish, which I understand completely, relieved to learn it has nothing to do with me, and everything to do with the black sheep of the family, the other daughter who has dropped out of school for no reason at all. His parents are wonderfully polite to me, and thankfully don’t ask what I am doing in New York or if I have children because the next thing you know, I’ll be exchanging recipes with his mother along with tips on how to deal with recalcitrant teenagers. His father can’t have been much older than me, and his mother, his mother, por amor de Dios, she is actually three years younger than me, I find out later, but looks ten years older, in fact both parents look older than their years, weighed down by the grinding dreariness of life, I guess, trapped by the treachery of the system, the American dream that promised everything but drained everyone of their dreams. No wonder Emilio wants out.

He also wants me to sleep over. And I tell him I can’t, it wouldn’t be right, it would be disrespectful to his parents, and fairly scandalous to the rest of his family, unless of course he makes a habit of bringing older women home to sleep over, which I sincerely doubt. And then I see his room, half-boy scout lair and half-thrift shop, and I see the clothesline tacked against the wall in the hallway and think, holy mother of God, he is the nicest boy, he really is, and he is so hot he should really be a model, but there is no way, there is absolutely no way I am going to sleep in his bed tonight and risk bumping into his mother or father if I have to go to the bathroom to pee, past the wife-beater vests and underwear hanging limply from the clothesline and there is absolutely no way I am going to make small talk with them in the morning still wearing last night’s clothes, smeared with the smell of sex while they sit down to eat their eggs, their eyes bleary with unnamed disappointments, past and future.

We leave the apartment and climb the stairs to the rooftop, past walls of peeling paint and ceilings with broken lights. The rooftop is barren and desolate, like a concrete bunker that was bombed and brusquely exposed to the night sky. Emilio pulls me to him and kisses me impatiently, while I unfasten his pants and wrap my hand around his hard, hot dick, finally freeing it from the torture of waiting. I feel like I know him so well, know exactly what he’ll do next, where his hands will go, how his lips will feel on my breasts and the hollow of my neck, how many times he can come in one night, how later he’ll want me to take him in my mouth and suck him off, and it’s nice, it’s always nice. It is foreign yet familiar, his desire for me, so consistent, so dependable, and it’s thrilling, in plain view of anyone who cares to wander into this abandoned terrace, and it’s also comforting, the certainty that he will always want me and never hurt me. I also know this is it for us, el último adiós. He sneaks his hands under my shorts, murmuring that I should have worn a dress instead, and inserts his fingers into my moist pussy. He tears open a condom packet and turns me around and makes me lean forward, my hands on the ledge of the rooftop wall for support, so he can enter me from behind.

Ahead of me is the Williamsburg Bridge, and there’s Manhattan beyond the East River, brimming with bright lights, beckoning me back to my world.