The Heated Conversation

The Heated Conversation

You can’t eat a child!” said Ebenezer.

The smile dropped from the beast’s face. Now, in its place, stood a nasty sort of snarl.

“And why not?” asked the beast. “You’ve brought me everything I’ve wanted before. Why are you turning your nose up at this one?”

“Because it’s wrong!” said Ebenezer. “You can’t go around eating children. There’s something very impolite about it.”

“Impolite? Did you say impolite?” asked the beast. “You didn’t think it was impolite when you brought me a Wintlorian purple-breasted parrot, and you didn’t think it impolite four hundred years ago when I asked you to bring me the last dodo.”

“But that was different!” said Ebenezer. “Animals aren’t the same as children.”

“That’s a silly way to think!” said the beast.

“No, it’s not. And I’m sorry, but I just won’t do it,” said Ebenezer. It was the first time he had stood up to the beast in over five hundred years.

The beast gave no sign that it was disappointed. In fact, it looked almost maddeningly calm.

“If that’s how you feel, Ebenezer, there’s nothing I can do,” said the beast. “And thank you for being so honest with me.”

“Um… that’s… well, that’s quite all right,” said Ebenezer. “Sorry I can’t be more helpful.”

Ebenezer walked toward the door, delighted and surprised by the fact that he had managed to say no to the beast. He was just turning the door handle, when the beast spoke again.

“Oh, by the way Ebenezer, I do hope you enjoy old age,” said the beast. “I really hope you enjoy having the wrinkles on your body, and the pains in your joints as you walk up the stairs.”

“What do you mean?” asked Ebenezer.

“I mean what I say,” said the beast. “I mean that I hope you are happy when old age starts weakening your bones and writing lines into your beautiful face.”

“None of that will happen,” says Ebenezer. “The potion will stop all of that from happening like it normally does, won’t it?”

“Oh, I’m sure it would, dear boy. But where are you going to get the potion from?” asked the beast. “You’re not getting it from me, unless you bring me what I want.”

“But—”

“No buts,” said the beast. “You need your potion by Saturday, and I want to eat a child before then. Bring one to me, and you will continue to live a long and happy life.”

“And if I don’t?”

“Then you shall die, Ebenezer. Without the potion, your body will give in to your old age, and you will be nothing more than a pile of bones. I would be most upset about it.”

Ebenezer wondered whether he cared that much about children after all. He didn’t really want to feed one to the beast, but he also didn’t think that any child was worth more than his own life.

“Are you sure there’s nothing else I can bring you to eat instead?” asked Ebenezer.

“A child is the only thing I want,” answered the beast.

“Well, then,” said Ebenezer. “Let me think about it.”

The thinking didn’t take very long.

“I’ve thought about it, and I think it’s a wonderful idea. There’s no reason why you shouldn’t have a child to eat,” said Ebenezer. “Would you mind vomiting out a large brown bag for me? Ideally the same size as the one you gave me when I went hunting in the South Pole.”

The beast hummed and wiggled and vomited out a strong, emperor penguin–sized bag. Ebenezer ran downstairs and jumped into the car with it.

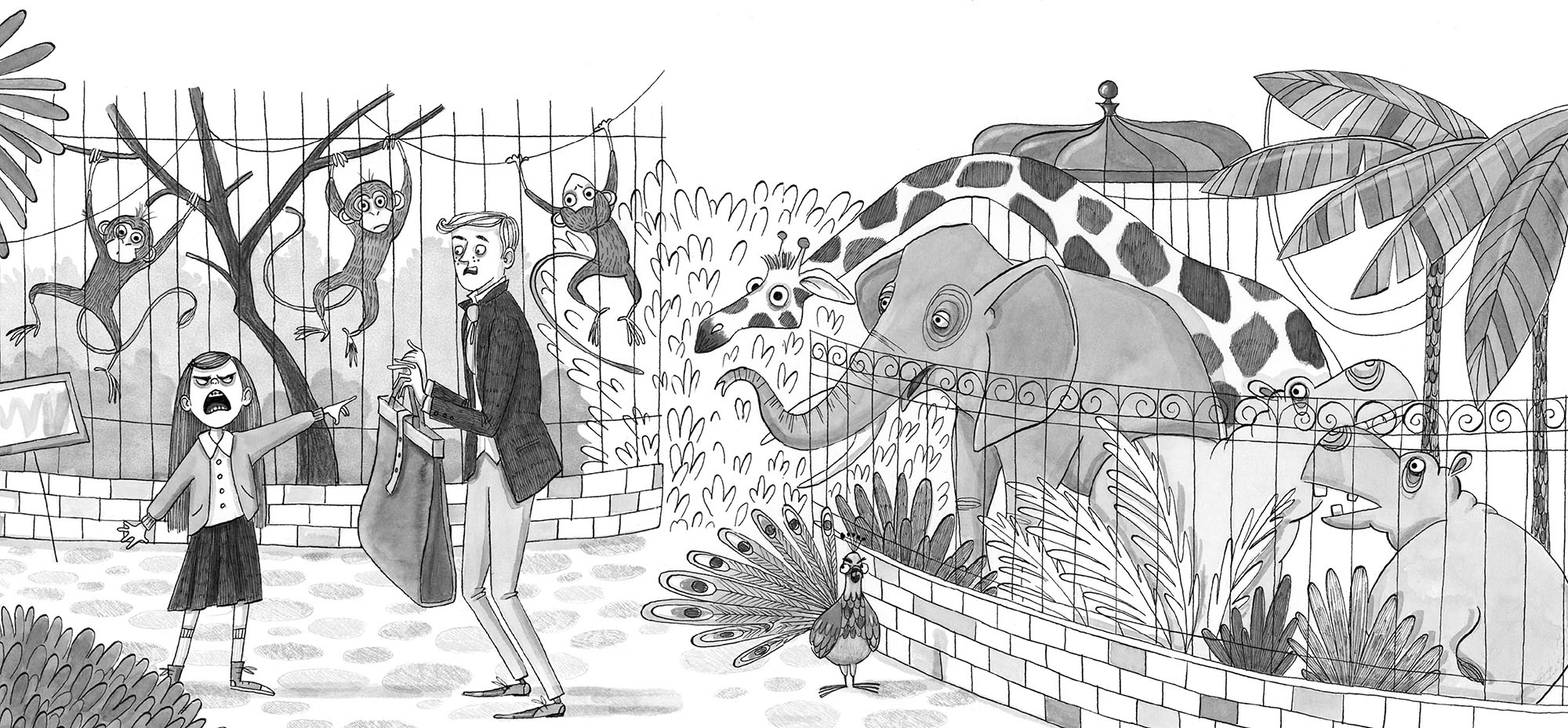

He drove straight to the zoo, beeping and weaving his way through the traffic with all the patience of a cranky toddler. He made it to the ticket office with just ten minutes to spare before closing time.

“Adult or child?” croaked the old lady at the ticket office. She was small and scaly, and looked like she might be better suited to the lizard enclosure.

“I want a child, please,” said Ebenezer breathlessly.

The lizard lady peered closely at Ebenezer and raised her thin eyebrows in a questioning manner.

“I mean, an adult ticket. Because I am an adult,” said Ebenezer quickly, as he laid down some coins. “It may surprise you to learn that I’m actually 511 years—”

The lizard lady didn’t care. She snatched the money and let Ebenezer and his bag through the barrier.

But Ebenezer didn’t focus on this. He was too busy congratulating himself.

He knew there would be children at the zoo, because he had spotted a few during the time he had kidnapped a peacock to feed to the beast, but he had no idea there would be so many. The place was an all-you-can-eat buffet of snot and nits and tiny fingernails.

Ebenezer approached a frowny girl who was standing near the elephant sanctuary. He opened his large brown bag and invited her to jump inside.

“Come on then,” said Ebenezer, when the girl refused to play ball. “I haven’t got all day.”

“DADDY! DADDY! IT’S A STRAAANGERRR!” shouted the girl.

Within moments a man (similarly frowny), marched up to Ebenezer. He shouted twelve rude words and made two nasty threats, before he led his daughter away.

Ebenezer shrugged, and then tried his bag trick on another child.

And then another.

And then another two more.

Every time he found a child, there was a blasted parent lurking somewhere nearby. Pretty much all of them had unpleasant things to say when they saw Ebenezer try to stuff their children into his bag.

Soon, the complaints mounted up, and Ebenezer was dragged back to his car by a security guard the lizard lady had brought with her. He finally accepted the fact that he would have to think of something else, when he received a lifetime ban notice from the head zookeeper.

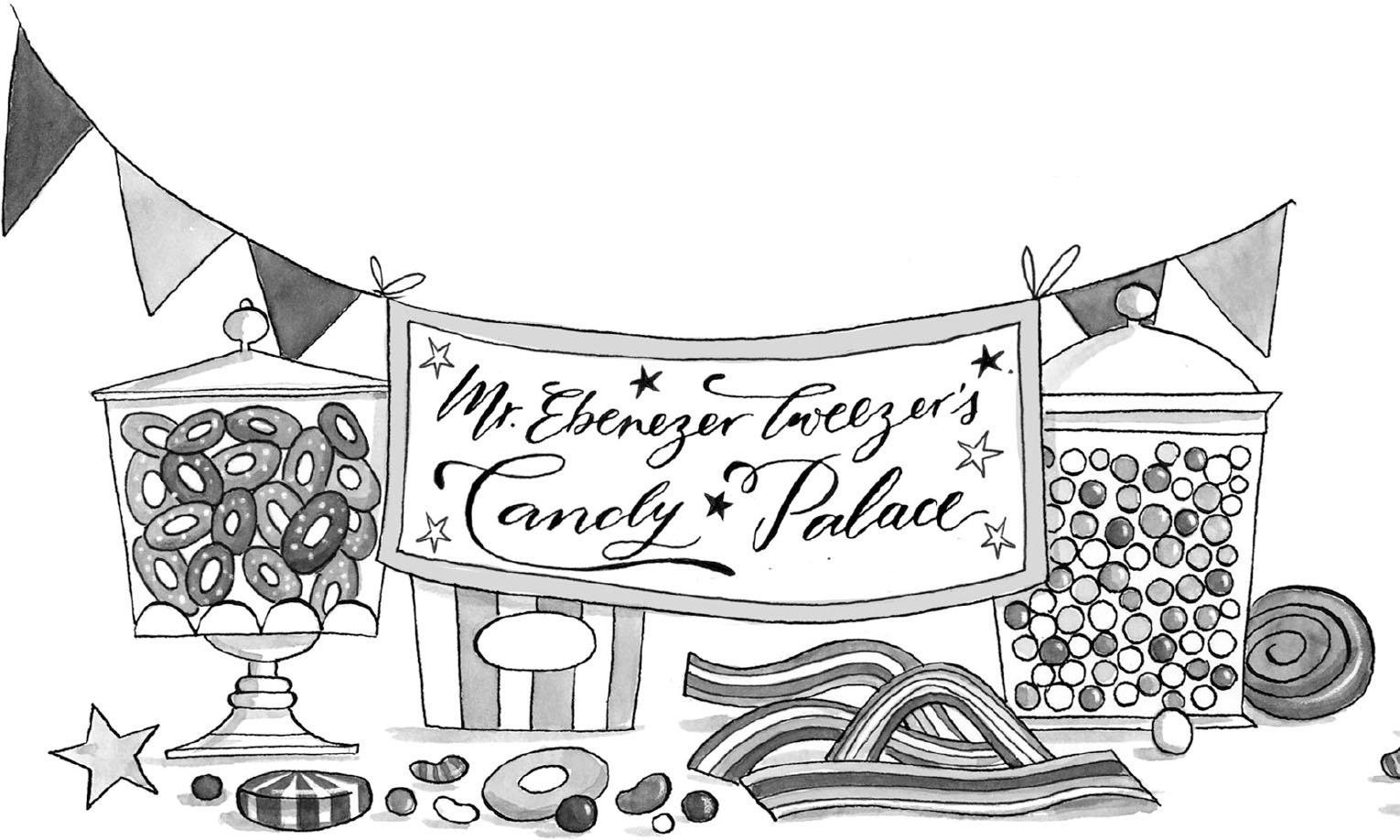

The something else that Ebenezer thought about was a sweetshop. Whenever Ebenezer went to his local sweetshop, there were always greedy children with sticky fingers and dirty mouths swarming around the place. And some of these children were there without their parents. The only adult who could get in Ebenezer’s way was the sweetshop’s eccentric and experimental owner, Miss Muddle—annoyingly, all the children seemed fascinated by her.

In order to get around this problem, Ebenezer decided to set up his own sweet stall. He got the beast to vomit out a banner, which read MR. EBENEZER TWEEZER’S CANDY PALACE, and he set up a table on the street, filled with all manner of sweet goodies that he sprinkled with sleeping powder so that he could easily transport the children to the beast’s attic.

After a short while, Ebenezer’s first customer arrived. He was a twelve-year-old named Eduardo Barnacle, who was in possession of the world’s third largest set of nostrils. They were wide enough to each hold a small orange.

“Well, well, well—what do we have here?” asked Eduardo. He bent over Ebenezer’s table and took a deep sniff of each of the sweet things on offer.

“We have licorice allsorts, Catherine wheels, strawberry fancies, sherbet pips, banana bonbons—the whole party.”

Eduardo sniffed again. The rims of his nostrils swelled and shrank greedily upon his nose.

“This is the strongest selection I’ve seen in a while. Congratulations, Mr. Tweezer,” said Eduardo. He was oddly confident in his ability to speak to grown-ups as if he were one. “How much will it cost if I purchase a sample of each one?”

“Two hundred and fifty-three pounds and sixty-two pence,” answered Ebenezer, a little too quickly. He wasn’t used to dealing with money, because he normally relied on the beast, so he didn’t really know how much things cost.

Eduardo shook his nostrils (and the rest of his head) sadly from side to side, and walked away from Mr. Ebenezer Tweezer’s Candy Palace. Ebenezer chased after him.

“Sorry, sorry—I got that all wrong. I meant to say eighty-five pounds and ninety-four pence. What a bargain!” he said.

Still, Eduardo continued to walk away, so Ebenezer offered the sweets to him for free. Then he offered to pay Eduardo to eat them.

“How much will you give me?” asked Eduardo.

“Seven hundred and forty-six pounds?” suggested Ebenezer.

“Well, clearly your sweets can’t be very good then. Good day, Mr. Tweezer.”

Eduardo marched back home, with his nostrils held high in the air, and refused to return. Ebenezer resumed his position behind the table, helped himself to a Catherine wheel, and pondered whether he should remain outside. He promptly fell asleep, face-first into a strawberry fancy, before he remembered the sleeping powder.

Seven hours later, in time with the sunrise, Ebenezer sat up, somewhat chilly from his night on the street. He decided that he had had quite enough of this sweetshop business.

“There has to be an easier way!” he said crossly to himself.

For the first time in his life, Ebenezer was sad that he didn’t have a family of his own. It would have saved so much time and energy if he could have just fed one of his children to the beast.

He went back to the house, changed clothes, ate some truffles on toast, and climbed into his car. He drove straight to the bird shop, where the bird-keeper was busy feeding some parakeets their breakfast.

“Good morning,” said Ebenezer.

“Ah, Mr. Tweezer!” said the bird-keeper. “So happy to see you. I had an awful dream about Patrick last night. I dreamed he was screaming for my help. Ain’t anything wrong with him, is there?”

“He was a bit uncomfortable last night,” said Ebenezer. “But I think it was just indigestion. That’s all over now, thankfully. He hasn’t screamed at all today.”

“Oh good, that’s such a relief. I was so worried,” said the bird-keeper. “So what can I do for you? Are you looking to buy a friend for the parrot?”

“In a way, yes. I’m looking for someone who will join Patrick in his new home.”

“Well, I got loads of them here. I had some society finches come in last week. Would you like to see them?”

“I actually have something in mind already,” said Ebenezer. “It’s a bit of an unusual request. I was wondering whether you might have any children for sale?”

“Did you say ‘canary’?”

“No, I said ‘children.’ I’m not fussy about size, and I don’t really mind whether it’s a boy or a girl.”

“Right…” The bird-keeper took a quick look around his shop. “Sorry, mate, but I don’t think we got any of those. Got a lovely little cockatoo, at a very reasonable price, if that works? Or a half-moon owl?”

“No, thank you, I only want a child. How about the one who came in here yesterday? I believe her name was ‘Bogoff’?”

“Never seen her before last night, I’m afraid. And hope I never see her again. The backpack turned out to be broken in several places, and that cookie was far too soggy,” said the bird-keeper, shaking his head.

“I see,” said Ebenezer. “I suppose I’ll have to try elsewhere.”

“Wait a mo,” said the bird-keeper, as Ebenezer started to leave. “Why are you wanting a child?”

“It’s just something I need. My life depends on it,” said Ebenezer.

“Ah, how sweet. I remember my wife and I felt the same before we had little Tommy. A child is a wonderful thing,” said the bird-keeper.

“This little Tommy, would you be willing to part with him? I’ll pay whatever price you ask,” said Ebenezer.

“He’s not for sale!” said the bird-keeper. “My wife would kill me.”

Well, it was worth a shot, thought Ebenezer. He started making his way toward the door again. His shoulders were slumped and he was feeling very sorry for himself.

“Oi!” said the bird-keeper. “You can’t give up just like that.”

“I don’t really know what else I can do,” said Ebenezer. “There are too many parents at the zoo.”

“Eh?” The bird-keeper frowned. “Haven’t you tried the orphanage?”

“The orphawhat?” asked Ebenezer. It was a word he had never heard before.

“Yeah, you should try the orphanage three streets down. Miss Fizzlewick runs it, and she’s got dozens of little ones who need a home.”

“But what about the parents?” asked Ebenezer.

“That’s the whole point, these children ain’t got no parents. The parents are dead, or lost, or just not around.”

Ebenezer was surprised. He had no idea that people had such sad lives.

“Do you think I’d be able to get one by Saturday?” he asked the bird-keeper.

“Don’t see why not.”

“Marvelous, absolutely marvelous!” Ebenezer opened his wallet and threw a wad-load of cash at the bird-keeper to thank him for the very excellent advice. “You’re a lifesaver!”

Ebenezer ran out of the shop and jumped back into his car. All he had to do now was find the orphanage.