THE NEW YORK OF TEXAS

Chapter Two

There is a man in town who can lift a schooner over a bar—a schooner of beer over a saloon counter.

—Galveston joke, 1878

The utility of the location of Galveston had been demonstrated once more, and Michel B. Menard decided to exploit it. Menard, the founder of the city, was born at La Prairie, north of Montreal, Canada, in 1805. Educated at a French school, he carried with him French manners and accent for the rest of his life. He worked as a voyageur for the Hudson Bay Company and later as an Indian trader for his uncle. Menard drifted westward with the Shawnee and in 1829 crossed into Texas at Nacogdoches. He later worked for Texas independence as a politician, as a representative to the Indians to forestall their alliance with Mexico, and as a funding agent in the United States.1

Menard’s control of the Galveston city site came through a complicated process. In 1833 the land he wanted could only go to Mexican-born citizens, so Juan N. Seguin, an acquaintance, applied for a headright of one league and labor of land (4,605 acres). As attorney for Seguin, Menard directed the location of the headright to the eastern end of Galveston Island and obtained a survey by Isaac N. Moreland. The war intervened. Then, on October 3, 1836, Menard, again as Seguin’s attorney, transferred the land to Thomas F. McKinney. McKinney resold it to Menard on December 10, 1836. Meanwhile, Menard and nine associates—Thomas F. McKinney, Samuel May Williams, Mosely Baker, John K. Allen, Augustus C. Allen, William H. Jack, William Hardin, A. J. Gates, and David White—petitioned the Republic of Texas for confirmation of the claim. This was granted on December 9, 1836, in exchange for $50,000 in cash or acceptable materials in New Orleans. The total amount had to be paid in four months.

Menard promised payment of the money to David White, one of the partners, out of the sale of lots. White would also receive 10 percent of the proceeds after the initial $50,000 payment. White, who was the Texas land agent in Mobile, then acknowledged receipt of payment and this was accepted as payment by the Republic. The transaction, therefore, was carried off without any real exchange of money or materials. The Republic later had trouble collecting from White. It was believed that he was often paid in land scrip (promissory notes based upon real estate), and that he extracted a commission of 7.5 percent.2 Such was the state of finance in the frontier Republic of Texas.

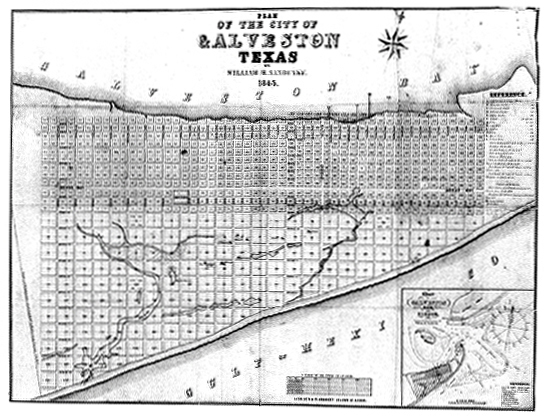

Levi Jones, who bought half of White’s interest in the enterprise, hired John D. Groesbeck to survey the site and divide the land into lots. Groesbeck, from New York, had come to Galveston in 1837 for health purposes. He laid out Galveston in a gridiron form patterned after Philadelphia, and set the configuration for the future. Avenues running parallel to the Bay and the Gulf he labeled in alphabetical order. The streets crossing at right angles were simply numbered in sequence. As time passed, letters and numbers changed. Avenue B, for example, became the “Strand,” Avenue J became “Broadway,” and Avenue E became “Postoffice.” Half-numbers assigned to the alphabet, such as M-1/2, had to be used as the city expanded toward the Gulf and the planners ran out of letters.3 Groesbeck completed his map in 1838.

Menard and his associates, during this time, organized the Galveston City Company for the sale of land. The board of directors—Menard, Thomas F. McKinney, Samuel May Williams, Mosely Baker, and John K. Allen—appointed Levi Jones as the general agent and ordered the first sale of lots for April 20, 1838. Thus, the city was born. The Republic confirmed the company charter and it continued to operate until 1909, when Maco Stewart bought the remaining assets and it went out of existence. The stock of the company rapidly depreciated down to 10 percent of its face value, but lots could be purchased from the company with its own stock. In the first year Jones sold seven hundred lots at an average price of $400 each. There were sixty families and over one hundred buildings by the end of that year. Menard, the principal founder, lived in Galveston until his death in 1856.4

In 1839 the Texas Congress granted incorporation to the city with a charter which specified the election of a mayor, recorder, treasurer, and eight aldermen. White male property-owners could vote, and they selected a hero of San Jacinto, the liberal, democratic John M. Allen, as mayor. He was a threat to the conservative control of the Galveston City Company, and in 1840 Samuel May Williams pushed a new city charter through the Congress. It called for a new election based upon a franchise requiring real estate ownership of at least $500 value. This eliminated one-half of the electorate. The conservatives then selected John H. Walton mayor, with a new board of aldermen. Allen, however, refused to give up and argued that his term still had one year to run. He took the archives, retreated to his home, and fortified it with two small cannons. The district court agreed with Walton, and Thomas F. McKinney led a posse to force surrender of the archives. This was accomplished without bloodshed, and the “charter war” came to an end. Four years later the city again changed the charter to get rid of the property qualification and grant the franchise to all white male taxpayers who had resided in the city for one year.5

The new town was not much to brag about. Francis C. Sheridan, a young Irishman in the British diplomatic service, arrived in 1839 and recorded his impressions in a journal. “The appearance of Galveston from the Harbour is singularly dreary,” he wrote. It was low, flat, sandy, and with few shrubs to be seen. “In short it looks like a piece of prairie that had quarelled with the main land and dissolved partnership.” Nearby Pelican Island offered a “similar hideousness,” and was occupied by nothing but pelicans. The beach, however, had “the whitest firmest, & most beautiful sand I ever saw.”

The men wore boots, trousers, and frock coats made from blankets. They carried pen knives for cutting tobacco, trimming their nails, and picking their teeth. For more violent purposes they carried pistols, and Bowie knives manufactured in England and labeled “Arkansas Genuine tooth-pick.” Business took place in the bars, and every new friendship had to be “wetted” as soon as possible. For those who bought drinks there was a luncheon of cold meat, pickles, bread and butter. There was also the benefit of the “spitting box.” “No one who has not seen & suffered by this most disgusting custom of the Yankees can form the faintest idea how universal & incessant is the practice. High & low, rich & poor, young & old chew, chew, chew & spit, spit, spit all the blessed day & most of the night.” Sheridan even observed a man teaching his two-year-old child to spit and praising the youngster’s successful efforts. Where the spitting box was missing, floors and fireplaces suffered.

Outside on the irregular streets he found a mixed group of people—English, American, German, Dutch, Italian, Mexican, and African. They possessed exaggerated manners and stopped to shake hands even if they had met the person but ten minutes earlier. One hurried soul shortened it by simply raising his hand and stating, “Well Sir—Your most”—and left. They auctioned off trade goods in the middle of the street, recognized the song “Will You Come to the Bower” as the Texas national anthem, and hummed the tune “Old Rosin the Bow” on the streets and wharves. Sheridan met “old” Sam Houston, who was fifty at the time, and one of the founding fathers of the town, Thomas F. McKinney.6

McKinney, born in Kentucky in 1801, early had worked as a merchant in the Santa Fe trade, as a keelboat man, and as a supply agent for the Texas patriots. He was a man of action with strong loyalties and dislikes. When Sheridan met him he was wearing a scarlet blanket frock coat and cleaning his teeth with a Bowie knife. He was considered a generous, honest man who ate when he was hungry and drank when he was dry. Although it galled him, he bore the title “Colonel,” which his old friend and partner Michel Menard stuck him with in jest.7

McKinney joined another “Colonel” in the merchant business. Samuel May Williams, who was born in Rhode Island in 1795, came to Texas to work for Stephen F. Austin. He became a Texas rebel and solicited funds for the Republic in the United States. In the early 1830’s he set up a mercantile business with McKinney at the mouth of the Brazos River. In the summer of 1837 they built a store and warehouse in Galveston, only to have it swept away by the hurricane of October. They quickly rebuilt, however, and constructed a wharf and the Tremont Hotel. Henry H. Williams, Samuel’s brother, bought the commission portion of the business in 1842. McKinney moved to Travis County, but Samuel May Williams continued in Galveston as a banker under the company title of McKinney and Williams.8

Sam Houston helped McKinney and Williams obtain the right to issue small denomination notes in 1841. On the basis of a charter approved by Texas in 1836, Williams with the aid of his brother opened the Commercial and Agricultural Bank in 1848. Shortly, Robert Mills, another Galveston merchant, endorsed and placed in circulation the notes from a wildcat bank in Mississippi. The anti-banking faction in Texas then began a ten-year campaign against “Williams paper” and “Mills paper.” Williams’ bank closed six months after his death in 1858. Mills lost his fortune in the Civil War and went bankrupt in 1867. Despite opposition and harrassment both men, in their time, provided responsible banking service to the state and to Texas business. The only valid complaint was that they charged a higher rate of interest than the bankers of New Orleans.9

MAP 3. Plan of the City of Galveston, by William H. Sandusky, 1845. Courtesy of the Barker Texas History Center.

Port activities provided the main thrust of Galveston’s economy in the nineteenth century. The pattern formed early and remained unchanged. Galveston factors bought the produce of agricultural Texas and shipped it to other ports. Conversely, they imported supplies for the farmer and sent them to inland merchants. The city served as a storage and shipping point, with the Galveston merchants providing some services and arranging for transportation. River steamers brought the cotton of Southeast Texas to the island wharves. Before the Civil War 90 percent of this cotton came from the bay area; 80 percent came from Houston via Buffalo Bayou. The Bayou City was Galveston’s door to Texas, where commerce shifted from water to land transportation. Houston had an immediate market around it which Galveston did not possess. In turn, Galveston served as Houston’s ocean port, where cotton moved from river steamer to deepwater ships. The two cities needed one another, and traffic was constant. The steamboat trip from Houston to Galveston left in the late afternoon and crossed the bay at night. The boats sent a shower of sparks upward from their funnels “leaving a brilliantly lighted trail in the prevailing southern breeze somewhat akin to a playful comet.”10

Galveston factors sent their cotton to New York, New Orleans, and Great Britain, along with hides, sugar, molasses, cattle, pecans, and cottonseed. Before the Civil War exports were twenty times greater in value than the imports, which came in small quantities and in great variety. In the mid-1870’s the main export still was cotton and the value of exports ten to eleven times greater than that of imports. To a large degree, then, the port of Galveston developed as a conduit whereby much more went out, in terms of value, than came in. The port was third in the nation for cotton exports in 1878, and fifth in 1882. Through the last half of the nineteenth century, excluding war years and bad crops, cotton receipts at the port gradually increased. In 1854 they amounted to 82,000 bales, and in 1900 they totaled 2,278,000 bales.11 Galveston was able to remain one of the important cotton ports, but it lost almost everything else.

Like other southern cities, Galveston continued dependent upon cotton while the northeastern United States industrialized. Manufacturing provided the future power and wealth of the nation, and agriculture diminished in comparison.12 Galveston never made the transition to industry and consequently lessened in comparison to cities which were able to change. It was not that Galveston leaders did not see the problem. They did, and argued that water supply was the difficulty.13 The analysis proved false, because the completion of the water system in the 1890’s did not bring a rush of industrialists to the island. Even the wealthy people of Galveston invested their money elsewhere. Why?

Galveston lay in harm’s way. People knew that it was subject to the onslaught of hurricanes. Why place expensive equipment, or a city for that matter, in such a place? O. P. Hurford, a newcomer to Galveston, explained in a letter to the editor in 1876 that he had heard in the commercial circles of Chicago, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, and New York that Galveston was unsafe for investment because of flooding. He advised, “There are to-day untold millions of Northern capital looking southward for investment, of which Galveston would receive her legitimate proportion if we could offer a reasonable argument that the island will not one day be washed away.”14

Arthur E. Stilwell, the railroad magnate who built Port Arthur as a terminus in the 1890’s, provided another example. He had a dream in which a voice said to him:

Locate your terminal city on the north shore of Sabine Lake. Connect with deep water via canal from your terminal city. Build the canal the same width at the top, the same depth and the same width at the bottom as the Suez Canal. Dig it on the west shore of the lake and put the earth on the east bank to protect the canal from any storm, for Galveston will some day be destroyed.15

About the same time a New York capitalist asked William H. Sinclair, the builder of the streetcar system in Galveston, why the city should expect any investment when fifteen houses had just been washed into the Gulf. The capitalist based his statement on a false newspaper article which appeared in both New York and California.16 This was but another example of the sort of reputation carried by the Island City.

Houston, meanwhile, surged ahead. In 1899, when Houston and Galveston were of comparable size, the Bayou City had 145 places of manufacturing to 100 for Galveston. Houston added twice as much value to the products it handled as Galveston did. In 1909 Houston had 249 places of manufacturing and Galveston 81. Houston added four times what Galveston did to the value of items handled. Oil exploitation brought industrialization to Texas in the early twentieth century. The pipelines led to Houston, Port Arthur, Beaumont, and Orange—but not to Galveston, which was still recovering from the devastation of 1900.17 Why put vulnerable pipes, tanks, and refineries in such a hazardous location? No one did.

The dream of industry, and hence greatness, nonetheless haunted Galvestonians. Studies in 1959 and in 1965 dashed long-standing illusions and indicated little potential for manufacturing in Galveston.18 Yet in the nineteenth century there were a few small factories. This gave some basis for the dream—what was once, might be again. Before the Civil War there were iron parts, soap, sash and door, furniture, and rope manufacturing. Gail Borden, Jr., briefly operated a meat biscuit plant, and there were cotton compresses. After the war small-scale factories produced flour, cottonseed oil, ice, and textiles, but not enough to engender an industrial “takeoff.” The largest industry in 1880, oddly enough, was printing, which employed 107 people and listed an investment of $287,000. This capital was three times greater than that of the flour mill which was next in line.19

As might be expected from their interest in cotton commerce, Galveston leaders placed their greatest emphasis on improving commercial rather than industrial facilities. It was understandable, moreover, that they stressed improvement of water rather than land connections. After all, Galveston was surrounded by water. It was the harbor which gave the city its natural advantage and was its greatest asset. What the leaders accomplished with the harbor and port insured Galveston’s continuance as a leading cotton point. What they were unable to do with railroad connections insured the success of Houston and other inland capitals. What should be kept in mind, however, is that Galveston did not control its destiny except in a limited way. Geography, weather, the technology of a nationwide system of railroads, and the shift in the national economy away from agriculture were much more important. It was fated that Galveston reach only the level of a mid-sized city. It was not destined by the dynamics that control urban growth to be anything more.

To promote commerce the businessmen established a Chamber of Commerce in 1845, reorganized in 1868, and founded a Cotton Exchange in 1873. The chamber gained a success in the mid-1870’s with the promotion of grain trade through Galveston from Denver and Kansas City. The Wharf Company built an elevator, and the first shipments left port in July 1875. The handling of grain remained an important piece of port business from that point onward.20 The Cotton Exchange began as a factors’ association to coordinate the grading and handling of cotton; under the lead of William L. Moody it reorganized into an exchange. It was an effort to strengthen Galveston’s position in the face of railroad development which threatened to carry cotton overland to the eastern ports. The exchange became part of the Chamber of Commerce in 1889.21

The history of railroad construction and control in Southeast Texas contrasted north-south direction versus east-west direction. Galveston and Houston, especially Galveston, wanted a north-south development which would bring commerce through them to the sea. The main national thrust of growth, however, was east-west—the transcontinental lines. Galveston was caught in a national trend, and lost.

Considering the muddy nature of the soil in the Houston-Galveston area, the difficulty of transport by ox wagon, and the expense of building roads, a railroad made good sense. It could run in all weather and in most directions, people were willing to invest, and the technology and equipment were available from the East. Although the Republic of Texas authorized four companies, and the citizens of Galveston and Houston talked about it, nothing was done until Sidney Sherman, allied with Boston capitalists, built the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos and Colorado Railway (BBB&C) in 1850–1856. Sherman offloaded the thirteen-ton engine for the line at Galveston in 1852. Fearing competition from Harrisburg, the eastern terminus, Houston entrepreneurs began railroad work, and by the time of the Civil War the Bayou City had become the railroad center of South Texas with lines reaching in all directions. After recovering from the war, Houston railways continued to grow, and in 1873 the Houston and Texas Central connected with the Missouri, Kansas and Texas near the Texas-Oklahoma border. Houston, and Galveston along with it, thus tapped into the vast intercontinental system. In 1876 Texas railroads converted to standard gauge and cars could roll from the Galveston docks to anywhere in the nation.22

Galveston, meanwhile, pursued its own schemes. One hundred and fifty citizens traveled by water on the Neptune and five miles over the new railroad at Harrisburg in 1853 to toast the new technology with champagne and claret. Galveston representatives promoted without success an idea of state-controlled railroads which would fan over the state and converge at Galveston. Before the war, at least, people on the island saw little to fear in Houston success. Since Galveston was the port for Houston, any commerce generated by the railroads would flow southward. There was a little nervousness about the eastern line toward New Orleans, but the Civil War halted that enterprise.23

The first railroad to reach the island was the Galveston, Houston and Henderson (GH&H). Backed by French loans and state land donations the promoters began construction in 1853. Because of the heat and severity of the work, the builders hired W. J. Kyle and B. F. Terry, the Brazos plantation owners who helped with the BBB&C, to use their slaves for digging embankments. Irish laborers, bolstered with whiskey as part of their wages, graded and laid the track imported from Great Britain. The citizens of Galveston voted $100,000 in bonds to finance a bridge across the bay, and in 1860 the boom of a cannon announced the first train from Houston.24

Despite the fact that it became a trunk line between Galveston and Houston and earned one-third more than other Texas railroads, the GH&H passed into receivership in 1867. It was sold in 1871 and controlled by Thomas W. Peirce of Boston. John Sealy took over as president in 1876 and saw to a change to standard gauge. In the early 1880’s the railroad got into financial trouble again and shortly became part of Jay Gould’s Missouri-Pacific system. Sealy told Gould that the cars leaked rainwater and the wet red-plushed cushions faded onto the ladies’ dresses. Gould replied that the cars should run only in dry weather and that the passengers should carry umbrellas.25 So much for the social responsibility of Jay Gould.

It was this railroad that first revealed urban rivalry between Galveston and Houston. When it built into the southern part of the Bayou City in 1858–1859, the Houston City Council refused it right-of-way to connect with the Houston and Texas Central. Merchants feared that the cars of cotton would roll straight through to Galveston without stopping in Houston. During the war, the Confederate commanding officer, General John B. Magruder, forced the connection for military efficiency, and in 1865 the connection became permanent.26 The rivalry grew worse when a group of Houston merchants formed the Houston Direct Navigation Company in 1866 to transfer cotton from river barges directly to ships in Galveston Bay without touching at Galveston. Houstonians also moved to deepen Buffalo Bayou and dreamed of creating an inland port at Houston.27

Charles Morgan, the chief shipowner of the Gulf Coast, made the dream a partial reality in the mid-1870’s when he took over the Houston Direct Navigation Company, dredged a twelve-foot deep channel with the help of Army engineers, founded the town of Clinton near Harrisburg on the bayou, and opened rail service to Houston. He did all of this to meet the competition of the east-west transcontinental rail lines, which had led to a 50 percent decline in his business.28 In the process Morgan abandoned Galveston. It was a common interpretation at the time that he left the Island City because of monopolistic wharf charges. This idea arose at least in part due to the concurrent vendetta of the Galveston Daily News against the Wharf Company (see discussion below). It was a convenient event to exploit. Morgan probably did find the rates too high, but he never commented on the matter. The Wharf Company said that Morgan never asked for lower rates; the charge that monopoly control forced fees much higher than those at other ports has never been substantiated. Morgan left in order to compete with the railroads. The shipowner died in 1878, and when the rail line between Houston and New Orleans opened in 1880, his successors abandoned Clinton.29

The Kansas City Journal of Commerce commented on the new situation of Galveston: “While the back door, so to speak, was closed, the trade was all forced to the Gulf to reach the markets of the world, and the interior was supplied from the same ports—cotton went to market that way, and bacon, flour and goods came in that way, for all the state/7 The opening of North Texas by railroads meant that cotton and trade goods could move to Kansas City and St. Louis more cheaply by other routes than through Galveston and Houston.30 That was the problem—not Houston rivalry, not Charles Morgan, not a Wharf Company monopoly.

Galveston had no control over this fundamental change in transportation technology. Its leaders, however, did what they could. They tried to improve rail connections and deepen the harbor in order to remain as competitive as possible.31 Led by Henry Rosenberg and Albert Somerville, Galveston businessmen formed the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railroad (GC&SF) in 1873. They collected $200,000 in subscriptions that year and persuaded the county to underwrite $500,000 for the enterprise. The county bonds were marketed at home. This is the largest amount raised by a city and county in Texas railroad history. It is a fact which offsets a common argument that Galvestonians refused to contribute to home railroad work. Another popular thought is that this line began in reaction to Houston quarantines for yellow fever. This is a good story, but there exists little evidence to support it. The businessmen were trying to build their own trade connections to compete with Houston and Charles Morgan.

Depression delayed the GC&SF, but in the spring of 1875 it pushed northwestward into the Brazos Valley. With only sixty miles of track and unable to purchase rolling stock, it had to be reorganized in 1879. George Sealy bought control of it and paid the county $10,000 for its $500,000 share. The company continued to build and reached Brenham in 1880, Belton and Fort Worth in 1881, and Lampasas in 1882. It had a price war with the Gould network in 1882 and experienced deep financial trouble in 1885. The stockholders authorized Sealy to negotiate with the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe. The AT&SF officials agreed to take over the road in 1886, but required it to build into the Indian Territory. After this enormous construction effort, through trains began to run to Galveston from Kansas City in June 1887.32

In 1884 there occurred one of the unsuccessful, but colorful attempts to build a narrow-gauge railroad down the island. This was the Galveston and Western, otherwise known as the “Little Susie.” It accomplished no more than thirteen miles of track, never made a profit, frequently changed ownership, and served mainly to transport tourists.33 More important was the coming of the Southern Pacific at the turn of the century. Through the effort of George Sealy in 1899 officials voted to allow Collis P. Huntington to use the west end flats owned by the city for the construction of a terminal. Huntington did not have the presentiment of Arthur Stilwell and determined to use Galveston as soon as it obtained deep water in its harbor. He worked with Congress to obtain funds for port improvement and began development of his site in 1900. He died before the great storm destroyed the half-constructed facility. Southern Pacific, nonetheless, picked up the pieces, finished the depot, and began operating in 1902.34

Railroad building had several secondary effects for Galvestonians. It created, for instance, a forty-two-year bitter argument with Houston over the “differential.” In the 1880’s interior shippers calculated their cost for Galveston by taking the rate to Houston and adding it to the water cost from Houston to the island. This added amount was usually less than a railroad would normally charge for hauling an item fifty miles. When created in 1891 the Texas Railroad Commission recognized the differential and permitted it to remain. Since steamship companies charged the same price from both places, Galveston agitated for elimination of the differential so that the two cities could compete evenly for the trade of Texas. It was a long fight filled with hearings, court battles, formal complaints, editorials, and election promises. By 1933 the differential had been eliminated on almost all items.35

Another secondary effect was the erection of bridges. Made of cedar and pine, the first railroad bridge was completed in 1860 and financed by the city for $130,000. It reached across the narrowest part of West Bay, 9,400 feet, from Eagle Grove on the island to Virginia Point on the mainland. Shipworms had already eaten much of it when the storm of 1867 carried away 5,200 feet of the trestle. The city had not regained any money from it, and now it had to be rebuilt. Trains, nonetheless, ran over a new bridge in June 1868. This time the span lasted until 1900. The Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe put up a bridge in 1877, and the Galveston, La Porte and Houston constructed another in 1896.36 The bridge which caused the most interest, however, was the one for wagons built in 1893.

During the Civil War the rebels put planks on the railroad bridge so that soldiers could walk on it. Afterward mainland farmers agitated for a bridge so they would not have to hire the sailboats of the “musquito” fleet to take produce to the Galveston market. They argued that a viaduct would result in lower food prices. Opponents pointed to the cost and to the useless land for thirty miles inland which was nothing but a “crawfish marsh.” That meant expensive roads for the county, and the travel by wagon would be no cheaper than by rail. In response to a farmer in Hitchcock, “The only jackass in Galveston” wrote in 1889:

Why should the taxpayers of Galveston city—which actually constitutes the whole county—be placed under a fresh load of taxation in order that Mr. S. can fetch in a load of onions occasionally without paying freight on them? The insular position of Galveston has been its protection from crime in the past and still remains its security. Why should this be destroyed to oblige Mr. S. at the expense of the city?37

The wagon bridge advocates won. The county financed the construction with $175,000 in bonds, and Major H. C. Ripley, an engineer who had worked on Galveston harbor, designed it. He used concrete piles to protect against the teredo and built the rest of cedar, pine, iron, and steel. The bridge featured ninety steel arches each spanning eighty feet with a drawbridge in the middle and a wooden plank roadbed. At 11,309.5 feet in length it was said to be the longest highway bridge in the world.38 On the day it opened a Galveston reporter met the first wagon. It was eighteen feet long, pulled by eleven yoke of oxen, contained a horticultural display from Dickinson, and was driven by an animated black man with a long whip and “well-adjusted sentences.”

Whoa!

You Red!

What’s de matter wid you, Ellick?

Go on dar!

You hear me, Bill?

What I feed you fur, Jim?

Gittup Red!

Whoa, Bill!

Hit you wid dis stick toreckly!

Pull ur dar, John!

You Red!

You Bill! G———d———your soul to h———. I’ll beat the G———d———grass outen you if you don’t go on dar!39

Judge W. B. Lockhart of the county court also made some interesting comments:

A great many people think that the bridge would pay for the building even if it accomplished no other purpose than to give confidence in the stability of the island and furnish a means of escape in case of a storm to those who are overtimid about the city’s being washed away. Of course, we who live here have no fears of this kind, but it would surprise a great many of our citizens to know how many people in the interior are deterred from visiting us by fear that a storm will come up while they are here and they would never again be able to reach the mainland.40

Indeed. The wagon bridge blew away in the 1900 hurricane and was not replaced. Besides the differential and the bridges, the railroads had one other important secondary effect. They destroyed Galveston’s cotton compress industry. It was as important to compact the cotton for shipment on rail cars as it was for overseas travel. By the 1880’s the compresses moved inland, and interior cotton centers such as Denison, Dallas, and St. Louis emerged. Island factors sometimes squeezed the cotton again into a high-density bale, but this technology also moved inland by 1920.41 Still, Galveston was able to remain a major shipping point for cotton while other Texas ports lost the trade. This was accomplished through harbor improvement.

The major trends of ocean transport in the nineteenth century involved a shift to steam power away from wind and sails, utilization of iron and steel to replace wood, and growth in size. Deeper drafts demanded deeper harbors, and the port was Galveston’s only commercial advantage. It is difficult to imagine any development of the city on this sand barrier island without that asset. Deep water and harbor improvement, therefore, became an early and constant concern of city leaders. The attention to the port continues to the present.

The water outside the natural, tidal channels was shallow and dangerous. Charles Hooton, who visited Galveston in 1841, observed the bay area close by:

Sprinkled with wrecks of various appearances and sizes—all alike gloomy, however, in their looks and associations—it strikes the heart of a stranger as a sort of ocean cemetery, a sea churchyard, in which broken masts and shattered timbers, half-buried in quicksands, seem to remain above the surface of the treacherous waters only to remind the living, like dead camels on a level desert, of the destruction that has gone before.42

When Ferdinand Roemer arrived in Texas in late 1845 only eleven feet of water was reported over the outer bar, and the largest ships had to anchor outside.43 Already depth was a problem. Such vessels had to be unloaded by lighter, a process which was slow and expensive. Also, there was shallow water at the bay shore of the city. Early visitors reached dry land by wading, riding the backs of sailors, or walking on unsteady planks. The Galveston City Company sold these flats as “wharf privileges” for the building of docks. Individuals and businesses, such as McKinney and Williams, built a series of wharves reaching across the flats to the channel, and in 1854 a consolidation of ownership began under the lead of Michel B. Menard, Ebenezer B. Nichols, and Henry H. Williams. The city challenged the right of this Galveston Wharf Company to take over the waterfront. The dispute began before the Civil War and continued afterward until 1869, when the city and the company reached a compromise. The city gained one-third partnership and representation, but not control, on the company board of directors. The Wharf Company took over city claims and completed the unification of the wharf area—thirty-one blocks along the bay front.44

Willard Richardson, the editor of the Galveston Daily News, in 1869 praised the consolidation as “the most important transaction as regards the future welfare of Galveston, that has ever taken place since the foundation of the city.”45 To the bewilderment of the company officials, the newspaper began an attack in 1871 and characterized the Wharf Company as a monopolistic octopus which said:

Where the sea creeps there creep I,

In the slimy ‘Flats’ I lie;

For I’m the Vampire of the Deep—

Sucking in both ship and yawl,

Sparing neither great nor small—

And all that I absorb I keep.

On the good old rule, the simple plan,

To keep all you get, and get all you can.46

The newspaper blamed high wharf charges for the loss of the Morgan business, and with a series of individual samples maintained the attack. “It is hard to conceive that a corporation of citizens, having the reputation for business forethought that the men have who compose the Galveston Wharf Company, would openly, willingly and flagrantly invite disaster and commercial ruin.”47 The company replied that the annual dividends rarely exceeded 6 percent and never went over 7 percent. In fact, from 1869 to 1926 the average dividend was 5.44 percent. That was not an excessive return on investment for that time, or for ours.

The company did not argue, however, that its wharfage was lower than others, and late in 1874 the company began to decrease the rates. Company income also declined, along with the amount of dividends—perhaps in part because of the depression of the time. Dividends amounted to 1.75 percent in 1878. In 1881 the newspaper concluded, “The Wharf Company today is possibly in better condition than ever before in its history, while its tariff of charges, since first the News had occasion to direct attention thereto, has been scaled to an extent that leaves no room to grumble, by comparison with facilities afforded.”48 The paper, thereafter, complained about overloaded facilities, and about the increase in capital stock which reduced city ownership to one-fourth, but it defended and praised the rate structure.49 What became more important to everyone was the quest for deep water.

Improvement upon nature for the benefit of commerce was not new. Human beings have been reshaping harbors and digging canals since the time of the ancient Greeks and Egyptians. For Galvestonians the first effort, other than clearing wrecks, came in 1850, when John Sydnor, Gail Borden, Jr., Samuel May Williams, and others put together the Galveston and Brazos Navigation Company to dredge a channel across West Bay to Quintana. Citizens subscribed $30,000 and the municipality borrowed $20,000 to start the project. David Bradbury, the contractor, completed the effort in 1855 at a cost of $340,000. The channel was fifty feet wide, three-and-a-half feet deep, and eight miles long. Its purpose was to reach the cotton trade of the Brazos and to provide a thoroughfare for emigrants to California. After the Civil War Bradbury deepened it to five feet, widened it to one hundred feet, and extended it seven miles. Stockholders considered cutting from the Brazos River into Matagorda Bay, which would give access to Corpus Christi, but this idea had to wait for the intracoastal canal of the twentieth century. For the moment railroads circumvented the need.50

Closer to home there was increasing concern about the sandbars obstructing the channels. Between Galveston Island and Bolivar Peninsula a tidal bore ran forty feet deep. Stretching across this natural channel in a semicircle pointing toward the Gulf was a sandbar twelve feet or so below the surface. A branch of this tidal bore coursed along the curving inner face of Galveston Island and formed Galveston harbor. Near the junction of the channels, pilots began to notice shoaling in 1843. This so-called inner bar continued to grow until it reached a depth of eight feet in 1869.51 Shallow-draft Morgan steamships, built for the Galveston trade, began to have trouble crossing the inner bar in 1868 and often had to wait for high tide.52

“It is discreditable to our intelligence as well as enterprise, to allow so small an obstruction to subject our commerce to so heavy a burden,” wrote the editor of the Galveston Daily News in 1868. Vessels which had to be serviced by lighters, the editor noted, gave opportunity for Houston barges to bypass Galveston. The Chamber of Commerce asked permission of the Reconstruction military authorities to allow a city tax for clearing the bar, but the federal officers refused. The city then set up a Board of Harbor Improvements. Led by Henry Rosenberg, the board raised $15,000 through the sale of city bonds, and adopted the plan of Captain Charles Fowler. The idea was to sink a series of piles to focus the current, rake the sandbar, and let the current wash it away. The goal was a twelve-foot depth.53

Eastward off the tip of the island toward Bolivar, Fowler drove three rows of cedar piles ten to twelve feet into the bottom. After appeal by the city government, the federal government began to help, and in 1873 the bar was twelve feet below the surface and sinking deeper. There was also an accumulation of sand on the Gulf side which restored five hundred acres to the end of the island.54 Success, but it was not enough. “We might have the yellow fever every year for a century,” said the newspaper in 1871. “We might persistently sit still and refuse to help railroads, and let our streets be hog-wallers—yet if we could put twenty feet of water on each of the two bars of our Harbor, we would prosper and become a great city.”55 The goal now was a twenty-foot depth.

What was successful on a small scale set the pattern for future improvement—use jetties to concentrate the current, and seek federal subsidy to pay for them. It made sense. Under the classification at the time, a first-class harbor could accommodate a ship drawing twenty-six feet of water at low tide. Second class meant twenty to twenty-six feet, and third class was less than twenty. On the Gulf Coast, Tampa and Pensacola ranked second class; Mobile and Galveston, third class. New Orleans was also a third-class port until jetty work by the federal government moved it into the first category. Galveston possessed the best harbor between New Orleans and Vera Cruz, and improvement at Galveston, according to Joseph Nimmo, the chief of the Bureau of Statistics, was “a work of great national importance.”56

Beginning in 1874, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers directed by Captain C. W. Howell launched a project to build two jetties parallel to each other reaching into the Gulf, one from the tip of Bolivar and the other from the tip of Galveston Island. The idea was to force the Bolivar tidal bore to scour the outer bar. The engineers used gabions—large wicker cylinders filled with sand—to build the jetties. They failed. Under a new director in 1880, the engineers tried to construct the jetties out of pine brush and cane mattresses weighted with stones. That did not work either, and the townspeople became restless.57

There was talk about the benefit of twenty-five- or thirty-foot water. Henry Seeligson, a Galveston banker, commented, “Deep water alone can solve the future of Galveston, and will invite to our port the deep water vessels of all nations, and cause the terminus of the railroads of our State to center at Galveston.” He thought further that Galveston should appeal to Congress for the money to carry out the recommendations of Captain James B. Eads. Famous for his work on the St. Louis bridge and for the construction of the successful jetties at New Orleans, Eads, passing through Galveston on the way to Tehuantepec, had visited the Cotton Exchange and talked to local leaders. He later wrote to say that he had heard of the failure at Galveston and that he thought the harbor could obtain twenty-five-foot water at a cost of $5 million.58

Citizens in 1881 at the Cotton Exchange organized a “Committee on Deep Water” to direct the effort, and the city government asked Eads for specific recommendations. The engineer replied that he could guarantee thirty feet at a cost of $7,750,000 with Congress providing the funds. That was an enormous amount of money, but the Deep Water Committee, led by William L. Moody, went to work in Washington, D.C., to acquire appropriate legislation. Moody, born in Virginia in 1828, came to Texas in 1852. He fought for the South in the Civil War, became a colonel, and returned to Galveston in 1866. He built a strong cotton and banking business, helped establish the Cotton Exchange, and served in the Texas legislature.59 Deep water was essential for his well-being.

To promote the Eads bill, the Galveston delegation and Eads tactlessly criticized the Army’s effort in the harbor. “The jetty which is finished is wrongly located,” said Eads. “The amount expended on it is wholly wasted, because of its mislocation.” He pointed out that submerged jetties as designed by the Army would not work because of wave action and friction. Jetties had to extend above the surface, needed to be close together, and should be made of stone.60 The Army engineers, embarrassed by the waste of $1,578,000 at Galveston, fought back. They did not want Eads in control of improvements at Galveston as designated in the bill. Fearing competition, representatives of New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago also opposed the work, and Galveston lost.61

Stung, the Deep Water Committee began over again, and looked for broader support. It sent representatives around Texas, first, to elicit help. To their surprise, committee members discovered a deep prejudice against the port. People believed that the wharf monopoly paid 70–100 percent dividends and that the merchants owned the company. The DWC offset that misinformation by pointing to the 1.5–5 percent dividends and the wide ownership of the Wharf Company.62 It also worked hard for out-of-state support.

After returning from a ceremony to open the Fort Worth and Denver Railroad, the Texas representatives met in Dallas and passed a resolution to promote a deep-water convention in Denver. Meanwhile, at Fort Worth in July 1888, a Texas convention agreed to support the construction of a first-class port at “any point on the coast of Texas.” In Colorado, where representatives of nine western states met in September 1888, the delegates adopted the Galveston resolution for a first-class harbor on the Texas coast at a site chosen by a panel of Army engineers. Despite competition from Aransas Pass and Sabine Pass, the Galveston group was self-confident. They had some special support. John Evans, governor of Colorado, wanted a transcontinental railroad for Denver. When that failed to come about, Evans turned to Texas and Galveston as the outlet for the Mile-High State. He helped organize the building of a railroad to Texas and worked to aid Galveston on the Eads bill. Evans was the temporary chairman of the convention in Denver, and better yet, he became the chairman of the panel of engineers to select the site.63

The Army chief of engineers appointed Lieutenant Colonel Henry M. Robert, Captain George L. Gillespie, and Colonel Jared A. Smith in 1889 to investigate the ports of Texas and make a recommendation. None of the men had ever been in the South. For Galveston it was fortunate that a new group of Army officers had taken over in 1885. They admitted that the work in Galveston had failed, and admitted similar failures at Charleston, South Carolina. They, moreover, adopted in large measure the suggestions of James B. Eads. For his part, Eads had died in 1887. That cleared the earlier difficulties.64

A second convention with Evans as chairman met at Topeka in 1889 and endorsed again the resolution for a first-class harbor on the northwestern part of the Gulf Coast. Two months later the engineers investigating the sites reported favorably for Galveston and said that $6,200,000 should be spent. This time Colonel Walter Gresham led the Deep Water Committee in Washington, D.C. Gresham, like Moody, was born in Virginia and fought for the South in the Civil War. He was a noted lawyer and railroad executive, and had worked for Galveston at the deep-water conventions in Fort Worth, Denver, and Topeka.65

The political salesmanship was thorough. Even President Grover Cleveland knew about Galveston and its quest. The editor of the Galveston Daily News, Alfred H. Belo, told him that Galveston was a great place to fish and Cleveland wanted to try it out. When the Senate approved the Galveston Harbor Bill in 1890, the Galveston Artillery Company set up its cannons on the beach and boomed a one-hundred-gun salute. A month later, after Cleveland signed the bill, the mayor ordered a holiday, and the whistles of the city—on steamships, trains, and factories—blasted the air for thirty minutes in celebration.66 Deep water had been won.

Work on the jetties, north and south, went on for the next few years. The engineers first built a railroad and trestle over the water. Then, from the cars they dropped five-ton blocks of sandstone to build a trapezoidal wall. When it reached the surface, they capped it with ten-ton granite squares so that it stood five feet above the water. The project cost $8,700,000. The engineers meant the jetties to do the job and endure.67 They did.

After some dredging in the channel, in October 1896, the largest cargo ship in the world, the British steamer Algoa, drawing twenty-one feet, tied up at the Galveston wharves. The size of vessels using the port jumped by 24 percent. In the next few years Galveston exports increased by 55 percent, and imports by 37 percent. In 1885–1886 the Island City shipped only 22 percent of the Texas cotton crop. In the 1897–1898 season it moved 64 percent and at the end of the century Galveston was the leading cotton port of the nation.68 Deep water was a triumph which saved the vitality of the city at a time when railroad transformations threatened to destroy it.

Although commerce with its railroads, harbor activities, and cotton trade constituted the main current in the Galveston economy of the nineteenth century, an important minor stream of tourism also evolved. Within a month after the City Company began to sell lots in 1838, the President of the Republic, Sam Houston, with some of the members of Congress took an excursion ride to Galveston from the nation’s capital on Buffalo Bayou. The seat of government at the time was none too comfortable and they probably needed a vacation. Littleton Fowler, a Methodist minister, accompanied them to his regret. On the boat he saw “great men in high life.” They stripped to their underwear in view of the shocked preacher. “Their Bacchanalian revels and bloodcurdling profanity made the pleasure boat a floating hell,” he recorded. It was too much for the delicate Fowler, and he physically collapsed after the trip.69

In December the same year Millie Gray passed through Galveston on the way to Houston. Behind a team of rough-looking but gentle horses she took the time to ride to the beach with her four children to gather seashells.70 Sheridan, the British diplomat, saved sand dollars from the beach, and like others, found them brittle and easily broken.71 Another traveler in 1875 thought the city expensive, but the beach a delight:

Couldn’t get a cigar or a cocktail under twenty-five cents and there was very little “proof” in the whisky or “Spanish” in the cigar. But then the beach. This is superb! magnificent! (if a man don’t care what he says). To the Galvestonian it is a joy forever. He gives his last five-dollar bill on a ride along that bare sand bank to hear what the wild waves are saying—though I did not learn that they ever communicated anything of importance.72

The tourist value of the beach began to be recognized toward the end of the century. People used it for swimming, driving their horses, courting, and gathering shells. Since swimming suits were not a common item of apparel and ladies were shocked easily in those days, there was a problem. As early as the Civil War the city had an ordinance against nude swimming between sunrise and sunset. There was a twenty-dollar fine for a violation. The city changed the ordinance in 1869, 1870, 1876, and 1877 as violations continued. The law of 1877 prohibited bathing in the Gulf between 16th and 27th Streets from 4:00 A.M. to 10:00 P.M. and anywhere else in the city between 6:00 A.M. and 8:00 P.M. unless “clothed in a costume sufficient to cover the body from neck to knee, arms excepted.”73

The Galveston Daily News in 1869 described how to make a bathing suit. Male and female styles were the same. It was best, according to the newspaper, to use twilled flannel, moreen, or serge. Stiff wool was preferred because it did not cling as much as other fabrics when wet. Colors could be white, gray, blue, checked, or plaid. The blouse was made like a sack with separate trousers full over the hips and loose at the ankles. A full skirt could be worn if desired. An alternative style included a Zouave jacket and trousers loose at the knees. The hair could be protected with an oilskin cap—a large round bag with a pull string along the edge.74

Naked swimming, nonetheless, remained common in the nineteenth century. The newspaper reported two hundred nude people on the Gulf beach on a summer day in 1867, and twenty boys in a natural state in 1869 kept the ladies from the bayside wharves and off the decks of ships. Cavorting unclad boys drove some women from the surf in 1874, and a mixed group of nude men and women swimming near Lufkin’s Wharf in 1879 shocked decent people. When Officer Williamson in 1881 could not force naked boys out of the water of the bay he gathered up their clothes and took them to the police station. In 1899 the police actually caught and fined a boy for swimming “au naturel.”75

Of course, thieves sometimes made off with unprotected clothing and valuables. Returning from a moonlight dip in 1868, a man found all of his personal items stolen, including his shirt buttons. In 1872 two young men from a boarding house left the beach water at 11:00 P.M. to find all of their clothing gone. They made it home all right, but the ladies were sitting on the gallery and they could not reach their rooms without being seen. They waited in a vacant field where the mosquitoes feasted upon them like “carpetbaggers upon the unhappy South” until the women finally retired. Embarrassment prevented a report to the police. The next year a horse took off with the clothes of a mixed group of men and women. They had driven to the beach and left dry apparel in the dray to change into after swimming. Left alone, the horse decided to walk home. The clothes were still in the wagon—all except two “panniers” and a pair of “palpitators,” which somehow were lost along the way.76

Despite such mishaps the beach became increasingly popular. Streetcars provided regular service to the Gulf shore in 1877, giving all classes of people access to the surf most of the time from early morning until midnight. Women and children visited the seashore in the morning, entire families in the evening. There was little undertow and it was relatively safe. A reporter in 1880 observed boys plunging into the surf with enthusiasm and ladies gathering up their skirts to wade and exclaiming “Ah” and “Oh.” There were small bathhouses to rent, some mounted on wheels that could be rolled into the water. “Now and then,” said the reporter, “there is a woman who shows to advantage in the prevailing style of bathing dress, but the majority of them when they leave the water look much the worse for wear as the wet garments hang closely to their forms.”77 Although he did not say so, the effect of the salt water was probably just as damaging to the appearance of the men.

Outside groups began to arrive at Galveston on excursion trips—a congressional delegation in 1873, the Missouri Valley Press Association in 1875, the state Democratic Convention in 1876, Kansas legislators in 1876, a trainload of tourists from St. Louis in 1877, and a fat man’s convention in 1891. The Gulf assumed the condition of high tide, according to a reporter, when the “phorty phunny phat phellows” entered the surf for their annual wash.78 Maggie Abercrombie, who prepared an article about Galveston County for American Sketch Book in 1881, wrote, “Galveston could be made the most delightful summer and winter resort if but half was known of its rare attractions.” She saw Galveston as purely a commercial city.79 Local businessmen, however, awakened to the opportunity.

The Galveston Surf Bathing Company took out a charter in 1881 to build bathhouses between 10th and 30th Streets, and the Galveston City Railway Company built the Galveston Pavilion at 21st Street and Avenue Q the same year. The streetcar company hoped to increase patronage by placing this two-story resort on the beach. Designed by Nicholas J. Clayton, the most important architect of the Island City, the Pavilion boasted sixteen thousand square feet of unobstructed floor space made possible by four steel arches which carried the load of the wooden structure. It was the first building in Texas to have electric lights, and it could accommodate five thousand people for dances and performances. In 1883, however, it burned to the ground in a twenty-five-minute fire. The fire engines had a hard time reaching it because of deep sand on the beach, and a musician who had been sleeping in the south tower was killed when he jumped from a window and landed on his back.80

The Pavilion lasted only two years, but this did not halt beach development. In 1878 the Galveston Daily News suggested the construction of a hotel on the Gulf side with galleries to take advantage of the sea breezes. In 1882, led by Colonel William H. Sinclair, president of the streetcar company, a public subscription financed the erection of the $260,000 Beach Hotel. Nicholas Clayton, the architect, placed it upon three hundred cedar piles driven into the sand. It was three stories high with two hundred rooms and eighteen-foot verandas. It was colorful: the building was mauve, the eaves were trimmed in a golden green, and the roof had an octagonal dome painted in large red and white stripes. It gave the impression of three pavilions with gables and ornate grillwork pushed together to form an enormous E configuration. It had a dining room, gentlemen’s parlor and reading room, saloon, grand staircase, electric and gas lighting, and water tanks in the dome. It opened July 4, 1883, after a grand celebration the night before.81

The Beach Hotel became the focal point for social activity. The front lawn provided a site for summer entertainment—fireworks, high-wire walkers, and bands.82 It was unprofitable, however, except when the railroads offered special rates to the city. Sinclair commented that management had “shown a great deal more enterprise than sense in building it.”83 It was sold in 1889 and resold in 1894. In 1898 the city health officer blocked the seasonal opening because of an “absolutely disgusting and disgraceful” discovery. For at least a decade the hotel had collected the waste products of its sewers in cesspools. Each night around 3:00 A.M. it flushed these by steam pressure into the nearby Gulf. A broken pipe taken up for repair revealed the practice. The city forced the hotel to connect with the city sewer system. While this was being done, the hotel burned under mysterious circumstances.84

The wooden structure was a tinderbox. On July 3, 1898, the night watchman’s dog disappeared. On July 4 the watchman discovered a fire in the boiler room, put it out, and bought a bull terrier. On July 22 the bull terrier disappeared and another fire started in the same place. This time the guard was too late and the Beach Hotel vanished in heat, flame, and smoke. The police arrested no arsonist, but the owner had taken out a $25,000 insurance policy on July 18.85

Across the city at his home the architect, Nicholas Clayton, anxiously watched the flames. It was terribly painful for this gentle, shy man, who was the first professional architect in the state, to witness the destruction of his art. He had come to Galveston in 1872 from Memphis to supervise the construction of the new Tremont Hotel. He stayed to design homes and buildings such as the Block-Oppenheimer Building on the Strand with its cast-iron balustrades; St. Mary’s Infirmary, which was the oldest hospital in Texas; the Stewart Title Building (Kauffman & Runge Building); next door, the Trueheart-Adriance Building; the W. L. Moody Building on the Strand with cast-iron columns; the Galveston News Building; the University of Texas Medical School, now known as “Old Red”; Ursuline Academy, which survived until Hurricane Carla in 1961; and one of the most elaborate homes ever built in Texas, the Gresham House, also known as the Bishop’s Palace.

Colonel Walter Gresham wanted the most elegant house in the state, and he got it. With eclectic abandon Clayton designed for the cramped site a stone mansion with four four-story towers topped with tiled cones, numerous chimneys, balconies, massive oak doors, sculpted stone facings, stained-glass windows, and delicate black iron grillwork. No one knows the exact cost, but it was great for the era—at least $250,000. In 1923 the Roman Catholic Diocese of Galveston bought it as a home for Bishop Christopher E. Byrne, and the Catholic prelate commented about his residence, “I never thought that a farm boy from Missouri would find a castle in the sky in far away Galveston.”86

Clayton dominated Galveston architecture during the last two decades of the century. Although some of his work was lost in the great fire of 1885 and the storm of 1900, much of it remained. After his death in 1916 his widow worried about a monument. Rabbi Henry Cohen responded, “Oh, you don’t need one, my dear Mary Lorena. He’s got them all over town. Just go around and read some cornerstones.”87 Since the city grew but slowly after 1900, Galveston architecture became frozen in space and time. The cornerstones are still there, and the Victorian architecture for which Galveston is famous today is the legacy of Nicholas Clayton.

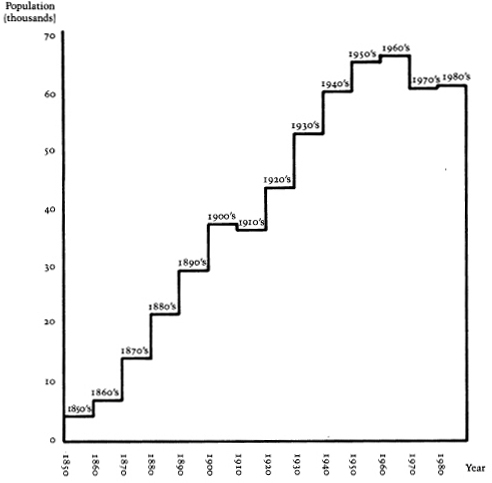

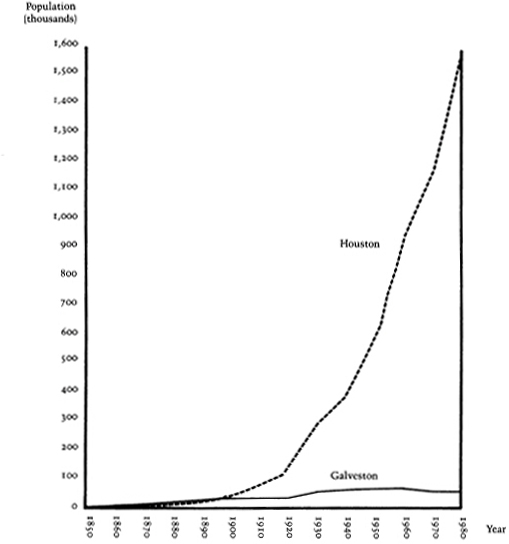

His accomplishment, also, is a tribute to the economic power of the city. Commerce, directly or indirectly, paid for his efforts. When Clayton arrived, Galveston was at its height of influence and prosperity. The moment was brief. With a population of almost fourteen thousand in 1870 and twenty-two thousand in 1880, Galveston ranked first in the state. The census of 1890, however, placed Dallas and San Antonio ahead, and in 1900 Houston, Galveston’s archrival, eased past. Compared to that in other cities, Galveston’s population growth slowed dramatically after 1890. In the 1960’s Galveston even lost 8 percent of its population and leveled off by 1970 at sixty-two thousand.88 Its destiny was that of a medium-sized city, and the lack of growth has been a frustration to its citizens. In 1940, when Galveston ranked seventh in the state, an editor remarked, “There would be no point in trying to analyze the reasons for that condition, but it is no disloyalty to say that Galveston didn’t make the progress it should. Discounting possible booms, this city has natural assets capable of supporting a considerably larger population.”89

FIGURE 1. Galveston City Population, 1850–1980. Source: Texas Almanac, 1982–1983 (Dallas: A. H. Belo, 1981), p. 189.

FIGURE 2. Galveston and Houston Populations, 1850–1980. Source: Texas Almanac, 1982–1983 (Dallas: A. H. Belo, 1981), p. 189.

The reason for the frustration is the mistaken thought that Galveston could have been something more than it is now. It really could not have accomplished anything else. Galveston’s fate was shaped by technology, location, and human reason. It was too risky, too reckless, and too uneconomic to place extensive businesses or population on an unstable edge of nature. It has been an error for islanders to measure importance according to population numbers. Greatness for Galveston came for reasons other than large size.

After the founding of the town, however, growth came rapidly. Galveston was a major gateway for the Republic, and the British consul reported in 1840 that it had grown from three houses to six hundred in three years. The population neared 4,000, and 228 ships of various sizes brought freight and 4,376 passengers to the docks in 1839.90 The consul was more enthusiastic than Charles Hooton, who visited the island in 1841:

From the sea, the appearance of Galveston is that of a fine city of great extent, built close upon the edge of the water; but its glory vanishes gradually in proportion to the nearness of the approach of the spectator, until on his arrival at the end of one of the long, rude, wood projections, called wharfs, which shoot out some quarter of a mile into the shallows of the bay, he finds nothing but a poor straggling collection of weather-boarded frame-houses, beautifully embellished with whitewash, (they may be mistaken for white marble from the Gulf), and extending, without measurable depth, about the length of two miles of string.91

On shore Hooton found wide, unpaved streets with ditches cut for drainage; a lack of fresh water; storekeepers who demanded 100 percent profit; pigs hunting snakes and cleaning garbage off the streets; and a hard-swearing, rough society where women were so scarce they had to marry in self-defense.92 He would have agreed with Three-legged Willie (Robert M. Williamson, an early Texas lawyer) who said, “Galveston is a low island of sand somewhere floating on the bosom of the Mexican Gulf, peopled by the lordliest crew of fatherless bipeds that ever trembled between hanging and drowning.”93

In the early 1840’s the village of Saccarap, an enclave settled by immigrants from Saccarappa, Maine, failed. It occupied the high land of Laffite’s camp near the bay shore and 9th, 10th, and 11th Streets. Amasa Turner, thinking it would be the center of town, built a wharf, hotel, and ice house there. It was too far from the deep water of the channel, however, and the center shifted to the Strand area.94 An anonymous poet wrote in 1843:

The late proud modern town

Of Saccarap, like Birnam Wood

Has left the place where once it stood;

The wharf is down, the hotel gone,

And desolation, cold and lone

Has made here dark and dismal den

Within the haunts of vanished men

And wild weeds grow, and kidlings play

Where Deacon Bailey once held sway.95

Although a reporter for the New York Sun said in 1847, “The streets are wide and straight, but their cleanliness is about on a par with New York, which is no compliment,” and a young man from Boston in 1859 found the town flat, rowdy, and drab with houses like “ugly Grecian boxes with pillars,” after its first decades Galveston began to lose its rough edges.96 Mrs. Isadore Dyer planted some imported oleander shrubs in her front yard in the 1840’s, and they flourished with pink and white flowers. She gave cuttings to others, and they spread so that now there are over sixty varieties on the island—white, yellow, pink, salmon, and red. Known as the flower of Saint Joseph, the oleander, which grows twenty to thirty feet tall, gave its name to the city as a sobriquet in the nineteenth century.97 It is ironic, however, that this plant, which adapted well to the saline soil and air and lent its beauty to the land, is toxic to human beings. Like Galveston itself, the oleander possesses an attraction that can be fatal.

Iron fronts imported from Philadelphia appeared on the new three-story business buildings downtown. Gas lighting, sidewalks, and shell pavement on the major streets also helped the appearance of the city. For the benefit and elevation of society, the town boasted a temperance group, dancing school, theatre, debating association, and newspapers.98 The Galveston Daily News, Texas’ oldest surviving newspaper, began in 1842. Willard Richardson bought it in 1844, and Alfred H. Belo joined him after the Civil War. Belo took over entirely in 1875 after Richardson’s death. He started the Dallas Morning News, and the Belo Corporation continued to run the Galveston paper into the twentieth century.99 Sharing the early period with the News were the Civilian and Gazette, the Daily Advertiser, Die Union, and Flake’s Bulletin. These newspapers were the chief source of information for the people of the town and the surrounding counties. They printed not just editorial opinion, but also technical and commercial information.

The other major source of information was the mail system. Peter J. Menard, brother of Michel Menard, became the first postmaster in 1838. The mail came by packet from New Orleans. Galveston then sent it to the interior of Texas. After the Republic granted incorporation, it required mail delivery to Houston twice a week. There were no stamps until 1847, and it cost twenty-five cents to send a letter two hundred miles.100 Telegraph service first came in 1854; information flow improved in 1859, when a telegraph wire was strung underneath the bridge built that year.101

Along with oleanders, new buildings, newspapers, and information sources, ministers also contributed to the transformation of early Galveston—at least to a degree. An early anecdote tells about three gamblers from New Orleans who found Galveston lacking in action. They turned virtuous and went to church. At the time for the collection the minister passed a hat, and the first gambler put in fifty cents. The second put in a dollar, and nudged the third man, who had fallen asleep. The sleepy gambler opened his eyes, saw the hat with money in the bottom, yawned, and said in a loud voice, “I pass.”102

The Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians all organized in 1840, the Episcopalians in 1841, and the Roman Catholics in 1847.103 When the Dublin-born Reverend Benjamin Eaton arrived in Galveston to establish Trinity Protestant Episcopal Church, he wrote to his bishop, “I know little about this town yet . . . but I have already seen and heard enough of the republic to cool my Texas fever, and to make me fear that I have left a most promising field (Wisconsin) for one where my exertions will not be half so useful . . . and where I shall experience almost every privation that a civilized man can endure.”104 He was close to being correct. After working for seventeen months to build a $4,500 church, this minister, who was once characterized as being “cold and so churchy that he made you feel as if religion was on ice from January to December and frozen stiff in Eternity,” saw the building damaged three months after completion by the hurricane of 1842. Eaton escaped through a window, made it safely to a hotel, and exclaimed, “My God, my God has forsaken me this night.” The congregation resurrected the building in six months, and after many changes the church endures to the present.105

Equally interesting is the early history of the First Baptist Church. When the Reverend James Huckins, a missionary agent of the American Baptist Home Mission Society, sailed into Galveston on a cold Friday evening in January 1840, he saw no need to leave the ship because he figured no Baptist would be found in such a dark, forlorn place. The next day he changed his mind, and organized a church within a week. This gaunt cleric with black eyes which moved independently of one another served as minister for First Baptist at various times.

The church records reveal the discipline of the congregation. People were taken off the rolls for gambling, intemperance, adultery, and joining the Methodists. Brother Jonathan Hughes failed to attend services. “Instead of letting his light so shine before him that they may see his good works, and glorify our Father which is in Heaven, he is a Stumbling Block to Sinners, and an injury to our church.” Huckins too had to resign, apparently for owning slaves, or, perhaps, dealing in the slave trade:

Bro. H. in settling in this country was obliged, for the comfort of his family, soon to be connected with the Institution of Slavery. This fact became known at the North, was used in Abolition papers, was employed in addresses, and became the cause of annoying enquiries in the form of epistolary correspondence—Even the Secretary of the Board wrote to him upon the subject.106

George Fellows, a neighbor in 1844, while on the way to Sunday school heard Huckins beating his female slave and spoke to the minister about it. The First Baptist Church, on the other hand, accepted black people on its membership rolls and supported them in a religious life. Huckins died administering to the wounded at Charleston during the Civil War, but while still in Galveston he baptized in the waters of the Gulf shore one of the fascinating characters of the town—Gail Borden, Jr.107

The great invention of condensed milk came after Borden’s time in Galveston, but he had condensation on his mind. He reduced sleep to six hours per night, and condensed meat for the use of travelers. After boiling eleven pounds of meat he acquired one pound of extract. He mixed this with flour, baked it, and produced a meat biscuit. Borden won a patent for it in 1850 and a gold medal at an international exposition in London in 1851. He hoped to sell it to the U.S. Army, explorers, and sailors, and with the aid of Ashbel Smith built a factory in Galveston to produce it. Meat biscuit, however, was a failure. Its nutritional value was all right, but it had poor flavor. People just did not like to eat it.

In Galveston, meanwhile, Borden served as the collector of customs and later as an agent of the Galveston City Company. He built a house near 34th Street and Avenue P, and became the second-largest landholder in town. He was a member of the first city government, searched for a source of fresh water for the city, constructed a portable bathhouse so women could surf-bathe in private, and invented a “terraqueous machine.” This was an amphibious vehicle powered by a sail which would turn wheels on land and a screw in the water. It failed on its maiden journey when frightened passengers panicked and dumped everyone overboard into the water. As his biographer, Joe B. Frantz, commented, “Some Galvestonians considered Gail Borden a genius; but more would have called him ‘peculiar.’ Almost all liked him.”108

Even if he could not give good flavor to meat biscuit, Borden did give society the spice of his personality. Providing interest also to society were the voluntary military companies. During the period of the Republic a Mexican invasion was feared. Units formed for self-defense, with the men providing their own weapons and uniforms. They drilled, marched, and held dances. Most organizations lasted only a short time, but the Galveston Artillery Company has endured to the present. Formed by clerks and businessmen, the company started September 13, 1840. It merged with the Fusiliers in 1844, the City Guards in 1857, the Washington Guards in 1881, and the Light Infantry in 1884. The men acquired several cannons including “El Cruel” and “El Fuerte,” salvaged from the wreck of the Tom Toby, which sank in the harbor during the 1837 storm. The company fired them for July 4, San Jacinto Day, and other momentous events.

After the Civil War, the Artillery Company reorganized in 1871 and in April of the following year paraded through the streets wearing blue coats, red pants, and red caps while carrying a white satin flag with the letters GAC formed in green, red, blue, and gold. The young ladies of the town had presented it to the unit, and that night the men repaid the generosity with a dance. The company became the elite social club of Galveston, and its annual ball marked the start of the debutante season.109 The Galveston Daily News recorded in 1885, “As matrimony, each year, removes from the active circle of society many of its choicest ornaments, so, in a measure, does this annual ball of the Artillery Company replenish it, and in the number of accomplished and beautiful debutantes this ball was exceptional.”110

The Civil War which interrupted the pleasant history of the Artillery Company was a major disruption for the Island City. It depopulated the city by at least 50 percent and demonstrated its vulnerability to invasion. The port was difficult to defend and militarily not worth the effort. It became a symbol, however, for both sides. For some islanders it became a test for survival, and they revealed a determination to remain regardless of consequences.

The state plunged into the maelstrom of secession early in 1861, and few stood against it. Ferdinand Flake, a spokesman for the German community and editor of Die Union, wrote a column criticizing the secession of South Carolina. Flake was not an abolitionist, and he was not disloyal. Yet a mob broke into his printing office, wrecked his press, and threw his type into an alley. Flake continued publication, nonetheless, with duplicate equipment which he had in his home.111

Another man of courage also spoke out. Sam Houston, governor of the state, opposed the action and after he lost went to Galveston to explain his position. Despite a threatening crowd the old man spoke from the balcony of the Tremont Hotel and pleaded, “Will you now reject these last counsels of your political father, and squander your political patrimony in riotous adventure, which I now tell you, and with something of prophetic ken, will land you in fire and rivers of blood?”112 It was of no avail; the madness continued.

While most of the men hurried to join newly formed military units and the women rushed to make cartridges and tents, others, some 25 percent of the eligible young men, hastened to the foreign consulates to claim citizenship and avoid conscription.113 Benjamin Theron, the French consul, particularly welcomed new citizens who wished to avoid Confederate service. He also complained to the United States about its bombardments of Galveston. As it turned out, both sides wanted to be rid of him.114 Business had begun to decline, shortages to appear, and unemployment to rise when the U.S.S. South Carolina appeared off the coast in July to enforce Lincoln’s blockade order. Captain James Alden issued a formal declaration and captured eleven vessels in five days. Business in Galveston collapsed, and the merchants did not have even enough money to pay their clerks.115

In preparation the Confederacy placed small forts at the extreme eastern point of the island, at Bolivar, and on Pelican Spit. An observation crew on top of the brick Hendley Building on the Strand watched ship movements with telescopes. Out of fun, and boredom, probably, the team at the Hendley created a club, the J.O.L.O., with elaborate titles for the club officers. It accepted pies from ladies, wrote elaborate resignations for members when they left for other duty, recorded club actions in the observation minutes, and never revealed the meaning of the initials.116

In early August the Confederate battery at San Luis Pass placed two cannon shots through the mainsail of the Sam Houston, a Union pilot boat captured by the blockade. In response the next day the South Carolina steamed toward the guns at Galveston and wildly exchanged a series of shots with them. One spectator, among the hundreds who rushed to the beach to witness the thirty-minute display, was killed. The Rebel gunners hit the hull of the Yankee ship three times with little damage, and the engagement ended when the South Carolina retired to sea.117