Chapter Three

“I say, landlord, that’s a dirty towel for a man to wipe on.”

“Well, you’re mighty particular. Sixty or seventy of my boarders have wiped on that towel this morning, and you are the first one to find fault.”

—Galveston joke, 1883

The greatest social change brought by the war and reconstruction concerned the status of black people. C.S.A. Major H. A. Wallace heard about it early. Messengers told him that troops had laid down their arms in Houston. He boarded the boat Island City and went to find out. It was true. Since there was neither Federal nor Confederate government at the moment, Wallace took over the boat as his own to set up a freight business between Houston and Galveston. When he reached the island on June 17 he found the blacks at the wharf throwing their hats in the air. “What is the matter?” Wallace asked.

“We’s free now.”

“What makes you free?”

“Yankees come down on ships on the outside to free us,” was the reply.1

General Order No. 3 issued by Major-General Gordon Granger on June 19, 1865, at Galveston made the emancipation official.

The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States “all slaves are free.” This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.

The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts, and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.2

This order abolished slavery in Texas forever, and it destroyed, likewise, the legal and economic structure which supported it. “June-teenth Day,” consequently, became an annual celebration for the black community.

Black people had been part of the Galveston population since the days of Aury and Laffite, and even Cabeza de Vaca. According to the census reports there were 678 slaves and 30 free blacks in the city in 1850, 1,178 slaves and 2 free blacks in 1860, and 3,007 blacks in 1870.3 This amounts to 16 percent of the total population in 1850, 16 percent in 1860, and 21 percent in 1870. The statistics are somewhat unreliable, but there was an antebellum effort to suppress free blacks in Galveston and Texas. Emigration into Texas was illegal, and the state required individual legislative approval for all free blacks. There were several in Galveston. The best known was “Major” Cary who had carried messages during the Texas Revolution and who had earned enough money to buy his freedom and that of his family. He ran a livery stable and was an expert rifleman.4

The law, however, was widely ignored, even though irritation with free blacks was constant. The chief justice of the county in 1848, for example, after numerous complaints by slave owners, gave notice to “free persons of color” against “harboring slaves, furnishing them with spiritous liquors and otherwise encouraging habits of idleness and dissipation.” Unless in the county at the time of Texas independence, or born since then, free blacks were to leave within thirty days.5 The order was not enforced. A city ordinance in 1851 required free blacks to give a bond for good conduct. “Free negroes and slaves do not do well together,” said the editor of the Civilian and Gazette that year, “but the freest negroes in the county are nominal slaves, too much indulged in by their owners. Such are the worst pest of this community.”6 A housewife wrote to her sister in 1855 after a black servant girl almost burned down the house by leaving a candle lighted on a pine box, “She is terribly aggravating. And so are they all in one way or another. The descendants of Ham are a curse to his brothers. There is nothing in the world more worthless than a free negro.”7

Pressure in the 1850’s forced most of the free blacks to choose a master for protection. They gave the master a small sum in return for a promise of care in sickness and old age. In return, the master took responsibility for their good conduct before the law. In 1860 there were only two free blacks remaining in Galveston—the most fashionable barber in town, and the dancing instructor who taught the white children and played fiddle at social events.8

All blacks, slave or free, were subject to special laws. There were ordinances about drinking, gambling, disorderly conduct, carrying weapons, employment, and obeying the 8:00 P.M. curfew. A black who threatened to strike a white person received thirty-nine lashes.9 Lucy, the slave of Joseph Daugherty, received more. She was an unhappy and rebellious house servant in a hotel. She was insolent, tried to run away, attempted to set the place on fire, and had to be confined to stocks at night. In anger, Lucy killed Mrs. Daugherty with a hatchet in the kitchen and dumped the body in the cistern. She confessed, and the jury found her guilty. On the second floor of the jail Lucy asked God for forgiveness, and the officials hanged her in front of twenty witnesses.10

Lucy was an extreme case. Anthony Hays, a free black from Boston, fought the system in his own way. He tried to hide a runaway slave on a ship for Boston, but was caught and fined $850 plus court costs. Since Hays could not pay the fine, the court sold him into slavery for life.11 Most blacks did not go so far. They worked at their jobs and lived the best they could. Since there was not much farming around Galveston, the blacks worked in the homes, hotels, restaurants, wharves, and stores. According to the 1860 census, two black females worked in a bawdy house.12

Slaves were bought and sold in Galveston, but there exists little evidence of a regular slave market. Indeed, with the lack of nearby agricultural land and the illegality of overseas slave traffic, there was little need for a market. Colonel John S. Sydnor, a mayor and auctioneer, is often mentioned in secondary sources of Galveston history as a person who maintained a slave market. The Galveston Weekly News reported in 1863 that he sold sixty blacks of all ages at an average price of $1,774 each, and one man for $3,500.13 The paper also noted the establishment of a depot for the sale of slaves in 1860.14 There is no evidence, however, of the sale of slaves, year in and year out, on a regular basis.

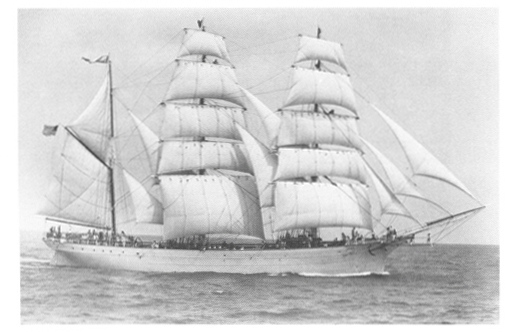

There may have been some smuggling of slaves from abroad, but again, as might be expected, the proof is scanty. Aury and Laffite, of course, dealt in slaves, and at the time of the Texas Revolution Monroe Edwards engaged in the traffic. The Texas ship Liberty chased two of his suspected slave ships to Pelican Island, but the cargo was on land and gone before anything could be done.15 In 1858 an American ship, Thomas Watson, with Mrs. M. J. Watson in charge, came to Galveston with a cargo of eighty-nine camels. On its way the ship lingered along the Gulf Coast, and to the British consul, Arthur T. Lynn, it smelled like a slave ship. Watson turned the camels loose to wander and starve on Galveston Island, and Lynn thought the animals only a ruse for smuggling. She wanted a clean bill of health for Liverpool, and the consul refused. She did not need a certificate for Liverpool, but she did need one to get into Havana. The Cuban port was a slave center, and Lynn, with others, was very suspicious. Watson eventually weighed anchor and vanished.16

When the Civil War ended, young blacks flocked into Galveston despite the warnings of the military and established an enclave at the old location of Saccarap.17 Emancipation, however, meant work, and the Army impressed unemployed blacks to cut wood and operate steamboats. City ordinances backed the requirement for employment, and the police shortly filled the jail with black vagrants. The sheriff discovered the prisoners trying to escape and decided to place them in chains. The blacks resisted, threw bricks, and the police opened fire. One prisoner who said that he “would not be ironed by any damned white man” was hit in the head, and another was struck in the body. Both died.18

There were complaints about drunken freedmen. Editor Ferdinand Flake explained, “In our walks about the city we notice many of our saloons make a practice of selling liquor to negroes. This should be stopped. Every one knows the effect of ardent spirits upon the black is very different to that upon the white man. The black, under its influence, is ready to make any engagement, to commit crime or mischief.”19 The newspaperman’s statement is interesting because it not only reflects a local attitude about blacks and their capacity to drink, but also reveals that the saloons, at least, were integrated.

The freed slaves obtained civil rights through military enforcement. They could now vote and participate in the court processes. The unsympathetic editor of the Galveston Daily News went to register and met a crowd of 150 “sons of Ham,” “the most loud-smelling that our nasal organs ever came in contact with.” They registered, received papers, and remarked, “Here am a’noder citizen made.”20 The editor in his observations and his use of a stereotyped vernacular was patronizing, but this was typical of the white newspapers until well into the twentieth century. Consider the following “amusing incident” printed by the News in 1877: A judge was sitting on the Galveston to Houston train in the smoking car when a six-foot-three-inch black man came into the car. He had a large mouth with thick lips “like two monster Bologna sausages, wide open and curling upward and downward as if swollen almost to bursting.” The judge sat upright and leaned over the seat in front of him to look. A conductor asked, “What do you think of it, Judge?” The magistrate continued to gaze, waved the conductor away, and said, “Hold still a minute, George, I’m waiting to see him finish turning wrong side out.”21

There was little sympathy or sensitivity, moreover, expressed by whites about the difficulties of transition from slavery to freedom. One exception was another judge in 1865. In his court James Hall brought an adultery suit against his wife, Mary, and an alienation of affection suit against Cleyborne Dyer. James and Mary Hall had married with the permission of their masters six to seven years before. There was no legal status to the marriage. When emancipation came, Mary Hall took a new husband, Dyer, and the Provost Marshall married them. The Galveston judge dismissed the case. Under the old law free blacks were treated as slaves and punished with whipping, branding, or death. A white person in a similar circumstance would have been fined $100 to $1,000. The judge prudently decided to wait for new statutes which would bring the law into accordance with the new circumstances.22

Within the black family there could be some humor over the transition. Daniel Ransom recalled a situation to interviewers in the 1930’s. His father, Henry Ransom, was a British citizen who worked on a whaling vessel. While in New Orleans before the Civil War he purchased his wife, Ellen, and later moved to Galveston, where he worked as a paperhanger. During family arguments, the son recalled, his father would say, “Don’t you talk to me like that. I bought you and paid for you.” Then, said the son, “She’d get riled up for sure.”23

Two institutions—the black churches and the U.S. Army—helped to ease the birth pangs of freedom. Through the Freedmen’s Bureau the Army assisted by establishing schools, taking care of the destitute, encouraging work, and adjudicating between the races. The whites generally disliked the bureau. On one occasion, the bureau took the side of a black in a dispute concerning a turkey, and sent a note to the Strand merchant. “That person, we suppose, not liking the tenor of the note,” reported the Galveston Daily News, “said that he wished the Freedmen’s Bureau was in ——, (never mind the word) a place much hotter than this gets to be, even in dog-days.” The bureau, in response, sent a guard to arrest the merchant.24

It was the Freedmen’s Bureau which brought George T. Ruby to Galveston from New Orleans in 1866. Born in New York in 1841 and reared in Maine, Ruby, a black man, acquired a liberal education and a lasting desire to win civil rights for his race. He promoted the immigration of blacks to Haiti, took heart from the war between North and South, and became a black educator in Louisiana at the end of hostilities. After being beaten almost to death by a white mob, he moved to Galveston as an agent of the Freedmen’s Bureau, intending to continue his work in education. His path, however, led into politics. Ruby joined the Union League and became its Texas president in 1868. He was appointed Deputy Collector of Customs for Galveston for 1868–1872 and was elected state senator from 1869 to 1873. In the legislature he supported not only the rights of blacks, but also the economic enhancement of his adopted city. Through his influence in the Republican Party Ruby affected patronage, but with the return of the Democrats his political career waned. He refused to run for re-election, and, subsequently, in 1874, returned to New Orleans. This New England black man, a temporary Texan, left behind, however, a legacy of biracial politics in Galveston and an example of black achievement at a time when most white Texans doubted such capacity in the minority race.25

The greatest accomplishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau was public education. Schools until this time were a private or parochial affair for white children. The bureau established public schools in churches and houses for whites and blacks and tried to make them self-sustaining. The schools had to be subsidized and met some public resistance, but the bureau, nonetheless, ran them for five years. In 1867 there were four schools by day and three at night. Unlike other places in Texas “Yankee teachers” could find a place to board in Galveston—mainly with German families.26 Between three and four hundred blacks attended school, and the desire for education was impressive. “We saw fathers and mothers together with their grown up children, all anxiously engaged in the pursuit of knowledge,” observed Ferdinand Flake.27

The Galveston Daily News generally supported the idea of education for all children, but had difficulty with the Freedmen’s Bureau on the mixing of the races.

Of the prime necessity of providing the means for the rising generation to acquire an ordinary education, there can be no difference of opinion, and in this State, if the matter was not mixed up with the eternal nigger, proper means for affording instruction would, doubtless, have been provided long ere this. . . . It will do no black child any good to be taught beside a white child, while the attempt would do the white child a good deal of injury, because the position is repugnant to its feelings, those of its parents, and of its associations, and all attempts at imparting an education under such circumstances would be worse than useless.28

For a decade after the end of Reconstruction and the Freedmen’s Bureau, Galveston County ran the public schools, amidst criticism and uncertain funding. Racial separation was the policy for students. “Colored children are not sufficiently advanced in civilization to be the fit companions of white children,” wrote the editor of the Galveston Daily News. “They are not as cleanly; they are not as well developed morally and intellectually.”29 In 1881 the citizens voted to take over the city schools, approved a tax levy, and elected trustees. The trustees hired a superintendent and in the fall opened a segregated system with one thousand white and four hundred black children.30 This set the pattern for the next seventy years.

There was also an early attempt at segregation on the streetcars, but it failed because of the shortage of cars.31 Separation of races on state railroads finally came in the 1880’s and was confirmed by the state in 1891, but white society was ready for it earlier. Blum’s Drug Store refused to sell soda water to blacks in 1872, and Henry Greenwall denied a seat to Mary Miller in the parquette circle of his theater because of race in 1875. The court held Greenwall guilty of deprivation of civil rights and assessed a minimum fine of $500. The judge commented that he wished it could be but one cent, and later dismissed the fine. In reaction, the black community met at the colored Methodist church and passed resolutions declaring the judge incompetent and prejudicial.32 By 1881 there was de facto division of races in churches, theaters, hotels, saloons, and barbershops. In the 1880’s blacks established their own fraternal organizations, sports teams, military drill units, and recreational facilities—in essence, the minority community put together a separate, parallel social structure.

The churches, a source of solace and inspiration, had always been segregated. Blacks sat in the gallery of white establishments or went to their own buildings. They held revival ceremonies, as did the whites, and developed their own style. One of the most popular black revivalists was the Reverend “Sin Killer” Griffin from Shreveport, Louisiana. Griffin, a large, brawny man with a voice that would put “seven steam calliopes to the blush” would leap, crawl, walk the aisles, and hoarsely shout, “Do you want to go to that golden city we have been talking about?” The audience would respond, “Yes, yes, yes! Hallelujah!” “You can go there brethren, but you must first be born again. Before you can write your name in the book of eternal life, you must be washed in the blood of the lamb. When you get there you will see your father and your mother and your brother and your sister. . . . Do you want to stay away from such a place and go to hell where the fiery demons are?” “No, no. Hallelujah! Amen!”33

A difference in style and a separation in social and economic matters were the pattern before the war and continued afterward, even though blacks possessed greater freedom to develop and more justice before the law. Prejudice, patronization, and stereotyping remained, and, as before, the flashpoint for the white majority was sex.

The newspaper complained in 1867 about a disorderly house kept by a black woman, Celia Miller, in the center of the city. Women of both races lived there and attracted all sorts of debased men at night. In another instance the editor reported a white woman living with a black drayman. She said she liked him and that others were doing the same. The paper bewailed the impudent, vulgar, audacious black prostitutes who used the alley behind the Episcopal Church as a place of assignation every night. “The hearts of the ‘trooly loil’ were made glad this morning by seeing one of the ‘boys in blue’ promenade market street holding in close embrace one of the most hideous negro wenches mortal eyes ever rested on,” the editor observed in 1869. The News reported that the black Texas senator, George T. Ruby, married a blonde, white woman, to the rejection of black Galveston women. It recorded other biracial marriages as well with disapproval or sarcasm.34

In such circumstances you would expect lynchings, and there were a few. In 1843 a mob sentenced a slave to hang the following day for an attempted “outrage” on a white woman. A judge denounced mob rule and released him. The mob recaptured the hapless black, held him until the original time of execution, put a rope around his neck, dragged him to a tenpin alley, and suspended him from a beam. The mob then cut off his head and threw the body into the bay. It was later retrieved and buried.35 Decent of them.

In 1865 a mob captured a black man and hanged him from a sign at the rear of a house on Winnie near 20th Street for a similar crime.36 Then, there were several times when you would expect a lynching and it did not occur. Mose White, a large, belligerent mulatto, for example, exposed himself and insulted a lady on the street. He hit the policeman who arrested him and attracted an excited group of one hundred people. A sailor wanted to kill him, but was restrained by the citizens. There was no lynching. Five years later, in 1883, a teenage black without an “extra bright intellect” tried to rape a five-year-old white girl in a stable. He was arrested, taken to jail, and charged. There was no attempt at lynching.37

The community gave opportunity to the greatest of the Texas black leaders of the time—Norris Wright Cuney. He was the son of a white Brazos Valley planter and a black mistress who bore him eight children. She was able to gain manumission for herself and seven children, and an education for three sons. Not bad. Cuney went to Pittsburgh for schooling and would have attended Oberlin except for the interruption of the Civil War. He returned to Galveston in 1865 and may have been involved with a gambling ring for several years. The record is unclear about this. In 1872, however, he became a customs inspector. Cuney ran for mayor in 1875 and spoke out against the injustice of the Greenwall theater incident. The white twelfth ward elected him alderman from 1883 to 1887, and he became important to the Republican Party.38

When George Ball bequeathed $50,000 for a new high school, his heirs offered $10,000 more if it was reserved for white students. Cuney and another black member of the council wanted the school open to all, but he acquiesced and Ball became a white facility. When white dock hands struck in 1883, Cuney organized black laborers as strikebreakers and successfully moved them onto the wharves. The business elite wanted cheap labor and Cuney supplied it. He thus drove a wedge between the economic classes of the white majority. He was the only person in Galveston to raise the flag in honor of Benjamin Harrison’s election, and a short time later received appointment as the chief collector of customs at the port of Galveston. It was a choice plum.39

During the last ten years of life the black leader suffered from tuberculosis, which finally killed him in 1898. This dapper man with his neat Prince Edward suits, constant cigars, friendly demeanor, and loping gait stood politically between the radicalism of W. E. B. DuBois and the conservatism of Booker T. Washington. He was no better nor worse than the other politicians of his day, and he offered an example of a competent black person.40 “Negroes are human beings,” he said, “and should be considered from that standpoint, if people would understand them as a race. In their actions and manner of life, they are prompted by very much the same motives actuating others of the human family.”41

The entire human family of Galveston—black, white, yellow, brown—suffered together the frequent visitations of death. The rate was awesome, and similar to that in other port cities in the United States. The Record of Interments, 1859–1872, lists many causes—consumption, typhoid, dysentery, “bad whiskey,” morphine, “shot,” “hooping cough,” “teething,” and “hanged in jail.”42 The major causes of death listed by the health officer for 1875, a normal year without epidemic, were consumption, convulsions, general debility, enteritis, and stillbirth. In the nineteenth century the Grim Reaper was fond of children, for in this same normal year, 243 deaths out of a total of 682 were under one year of age. The National Board of Health in 1881 calculated the Galveston mortality rate at 25.8 per 1,000 people. The white rate was 18.2 and the black, 49.3. Death also was partial to blacks.43

The greatest epidemic killer was yellow fever. It was a virus transmitted from one person to another by mosquitoes. The etiology was unknown until Walter Reed’s courageous experiments in Cuba in the early twentieth century. Before this, people understood that the disease came in the summer and disappeared with cold weather, especially after a heavy frost. They also knew that it spread through human contact, and that if it did not kill you, immunity was gained. Galveston, of course, always produced hordes of mosquitoes, rarely experienced frost, had a constant stream of unexposed immigrants, and carried on foreign commerce with Mexico and the Caribbean, where yellow fever was endemic. There were few window screens until the 1890’s. Galveston, therefore, was extremely vulnerable.

The island suffered epidemics of yellow fever in 1839, 1844, 1847, 1853, 1854, 1858, 1859, 1864, 1866, 1867, 1870, and 1873. Symptoms included chills, fever, headache, muscle aches, nervousness, jaundice of the eyes and skin, coma, and regurgitation. Internal bleeding in the last stages caused discharges to turn the color of coffee. It was a fatal symptom. After the appearance of “black vomit,” victims usually died. For those who survived, there was a long convalescence and a danger of relapse that could be as bad as the initial onslaught of the disease. Treatment varied with the physicians—none of them knew what they were doing—but consisted generally of confinement to bed, mustard baths for the feet and plasters on the stomach, cold compresses on the forehead, moderate food, warm tea, and no busybodies in the room. Of those who caught the disease one-fifth to one-fourth died. This often amounted to one-tenth of the population—a decimation.44 It meant that as much as half the town—or, in the case of 1839, almost everyone—would be sick with fever. In that year a small ship came to the port from Vera Cruz and the captain asked Levi Jones to examine his sick son. Jones, a retired physician, diagnosed the illness as yellow fever. The boy was beyond aid and shortly died. The father as well succumbed in the next twenty-four hours, and the terror-stricken crew carrying the disease with them fled into the town.45 Nicholas Labadie wrote his nephew shortly after Christmas:

I was rejoiced to hear from you both, but could not but shed a tear on the little presents your kind wife sent to Mrs. Labadie: Alas! they are yet on my shelves and I feel not courage enough to taste or eat them as she is no more to this world and has gone to the land of spirits. The epidemic which visited our infant city in October and November became a scourge to me, all my household became attacked at one time; my two little daughters recovered, my carpenter died on Sunday night, my clerk of the black vomit expired on Monday night, and my poor wife breathed her last about two hours after Nov 5th of the congestive fever [after] only six days of sickness.46

Another bad fever year came during Reconstruction in 1867. People returned to Galveston after the war, commerce recovered, and federal troops occupied the city. There were thousands of people who had never been exposed to “yellow jack,” and there was heavy rainfall in the spring and summer. The newspaper registered complaints about stagnant water on the streets and underneath houses. There were so many mosquitoes that if you were exposed at night, as one poor man was after he chased a burglar, your face would be swollen with bites.47 The stage was set for epidemic.

In late June, after reports of yellow fever in New Orleans and Indianola, the Galveston Daily News promised to give notice of any local appearance. It was already on the way. A young German traveler, George H. Moller, passed through Indianola and on to Galveston. He arrived June 28 and died July 3 with black vomit. The newspaper faithfully reported his death on July 5 and urged unacclimatized German immigrants to leave for the safety of the interior.48

Often there was reluctance to acknowledge the presence of illness—it was bad for business, and people did not like to face the facts. Greensville Dowell, a former C.S.A. Army doctor in Galveston, was in charge of the city hospital. He had diagnosed yellow fever in 1864 and was threatened with a court-martial for his effort. Still, he did not flinch in 1867. People were already calling him alarmist when he performed a post-morten exam on an early victim in the presence of the best private doctor in town. Dowell found black vomit in the stomach and held it up in his hand. “Mr. B.,” the other physician, said, “Now Dowell, if yellow fever should break out here, don’t you say that this is a case of yellow fever, and that is black vomit.” Dowell retorted, “It is yellow fever; this is black vomit. I do not care who says to the contrary.” With some justice “B.” later caught the fever, but recovered.49

On July 30 the Galveston Daily News warned people that they should leave the city, although it was free of disease at the moment. On July 31, however, the equivocal newspaper noted five deaths in the past three days, and thought it nothing to become excited about. On August 2 the editor admitted, “We now tell the public candidly that yellow fever is epidemic.” Some five thousand people fled, probably, one-third of the population, and spread the fever along the inland train and stage routes. Business came to a standstill. The banks refused to loan money; debtors refused to pay their bills. They waited to see who would die and would not have to be paid. Ice became scarce and high-priced. There were 22 deaths in July, 596 in August, and 482 in September. Probably, three-fourths of the population caught the disease. A total 1,150 died, and at a rate of 20 per day.50

Major-General Charles Griffin, the head of military affairs in Texas, perished, and a worker at the barracks observed:

Every morning when the sun rose and the roll was called many familiar faces had disappeared forever. Merry, laughing and buoyant with life and spirits in the evening, silent and stiff in the arms of death in the morning. . . . Disease lurked in the sands, in the water, in the wind. The sun rose and set, the waters rose and fell, and the victims of the yellow fever scourge silently succumbed to their fate. It was a dreadful summer.51

Burning tar fumigated the air of the city, grass filled with small green frogs grew rank on the Strand, and ringing of church bells for the deceased was so constant that it irritated the sick and living. Amelia Barr, who had moved with her husband and family to Galveston in 1866, observed the beds of the dying drawn close to open windows—white faces with cracked ice to cool them, moaning, raving, shrieking, vomiting, and a strong, sickly smell of yellow fever mixed with the heavy, sweet odor of oleanders. She felt that the ghosts of Laffite’s pirates haunted the house she lived in, and her own family fell ill. Her son Alexander while dying kept asking, “Who is that man waiting for me in the next room?” They all heard the heavy footfalls, but no one was there. The father held her other son while he died.

“Papa, what is the matter with my brother?”

“He is very ill, Calvin.”

“Is he dying?”

“Yes.”

“Tell him to wait for me. I am dying, too, Papa. I cannot see you! I am blind! Kiss me, Papa.”52

Her husband, Robert, after hearing his long-dead father calling him, also expired. Mrs. Barr survived, however, along with the three daughters. After suffering through the fever she gave birth to a son in December. He was born “yellow as gold” in color and died three months later. She thus lost all the male members of her family. She endured the hurricane of October and during the rebuilding period ran a boarding house. In 1868, leaving behind the four graves of her family, Amelia Barr departed for a new career in writing in New York.53

For Amelia Barr, Galveston was a “city of dreadful death.”54 There was little to do except help each other ease the pain, and await cold weather. It came in late November, but the number of victims already was declining. The fever had burned up the available fuel and had nowhere else to go. Volunteers, often people who had had the disease and were thus immune, joined a branch of the Howard Association, a national philanthropic organization. The group collected funds, disbursed money, nursed, and sent medical personnel to help other places. The association record book indicates a formal establishment in March 1854 with Reverend James Huckins acting as chairman and James W. Moore as president. The association may have existed as early as 1844 in Galveston, and it lasted at least until 1882.55 In 1867 the Howard Association provided nurses and medicine, and sent people to the hospital. It spent $8,000, including $100 donated by Gail Borden, Jr., in New York, and provided nurses for Brenham and Alleyton. It ceased its work for this epidemic on October 11 and estimated that the disease covered 200 miles of coastline to a depth of 125 miles, from Galveston to Corpus Christi.56 In the record book an anonymous member later recorded these verses:

I see him tall and gaunt and grim,

As he stalks in the moonlight air.

He moves so fleet on his legs so slim,

And halts and runs with a crazy whim

That he seems to touch everywhere.

He is pausing now, at a humble place,

And waving his skeleton hand,

A father comes out, with a reddened face,

And shudders to meet his hot embrace,

Then reels to the silent land.

A wail comes up, from the orphan group,

As the hearse moves slowly away,

But the fiend will stifle their cries with a swoop,

Tomorrow those flowers will wither and droop,

’Tis only the work of a day.57

The most powerful nineteenth-century weapon against “yellow jack” was quarantine, and the technique was responsible for the drop in yellow fever mortality after 1873. Twenty years earlier Ashbel Smith, the leading Texas medical authority, had written a letter to a Houston newspaper which claimed quarantine was an ineffective measure. He cited Galveston as an example. The difficulty, however, was not with the insufficiency of the idea, but with the poor enforcement of the barrier. In 1853 when Smith wrote, for instance, the captain of the Mexico from the infected port of New Orleans circumvented the quarantine by landing his passengers on the Gulf beach. They were into the city before Galveston authorities could stop them.58 Despite the fact that quarantine did not work at this time, it was, nonetheless, Galveston’s first concerted attempt.

As the debate over the efficacy of quarantine continued, there developed additional incentive—unmitigated fear. When yellow fever hit Galveston in 1870, widespread panic seized the coast. A militia armed with shotguns and bludgeons stopped a trainload of fleeing Galvestonians at the Houston city limit. The train returned to the island “butt end foremost,” but not before most of the passengers scattered in all directions and walked into the Bayou City by different routes. Houston placed a quarantine on Galveston, turned other trains back with armed force, and threatened to tear up the track. Other towns followed Houston’s lead, and Galveston closed off trade with New Orleans. Crescent City merchants accused Galveston of using quarantine for its own profit, but this was not true. The motive was well-justified fear, and traffic ceased all along the Texas coast. Only sixteen persons died that year in Galveston.59 The lesson was plain.

The same thing happened in 1873–panic; sporadic, but tight quarantines; and complaints from merchants. Seven people died that year. In 1876 when yellow fever appeared in New Orleans, the state quarantine officer cut off the Louisiana port, and no appeal from Houston, Galveston, or New Orleans businessmen budged him.60 There was no yellow fever in Galveston that year, no deaths. The lesson had been learned. Quarantine was used thereafter as a preventive technique. It was applied quickly, rigorously, and sometimes viciously. But quarantine halted the scourge of “yellow jack” until science in the twentieth century provided understanding and new technologies to fight the disease.

Ironically, it was the comparatively high incidence of disease in Galveston which brought to it the city’s most prestigious institution, the University of Texas Medical Branch. Ashbel Smith played the key role. He was a small, ugly man with strong opinions and a feisty temper. Known as “Old Ashbarrel” behind his back, Smith never married, held women in low esteem, and yet exhibited courtly manners. Born in Connecticut in 1805, he studied medicine at Yale and in Paris. He arrived in Texas shortly after the revolution and became the first surgeon general of Texas. He served in the Texas legislature, fought in the War with Mexico, and suffered injury in the defense of the South at Shiloh. He owned a large plantation called “Evergreen” on Galveston Bay, accumulated a four-thousand-volume library, and wrote the first learned medical treatise in Texas. For this study of yellow fever in Galveston in 1839, Smith inspected bodies and tasted black vomit. He did not recognize the mosquito as the vector, but he did recommend cleaning and draining as preventive measures.61

His colleague, Greensville Dowell, helped start Galveston Medical College in 1865, but ran into trouble because of his equally contentious nature. Because of dissension between Dowell and the faculty, the college faltered, and a young man studying medicine at the city hospital thought the school a “humbug, a swindle in every sence [sic] of the word.” The critic liked the hospital, though, where “any disease nearly that one wishes to study can be found.” He treated “a very interesting case,” of a sailor who had fallen from the top of a ship and whose broken thigh bone had stuck into the wooden deck.62

Smith helped Dowell reorganize the school into Texas Medical College in 1873, and worked for the location of the state institution in Galveston. At this crucial juncture Smith was both a trustee of the University of Texas and president of the Texas State Medical Association. Various cities competed for the colleges. Austin and Tyler wanted the whole system, including the medical school. Houston and Galveston wanted the medical branch and threatened to throw everything to Tyler unless Austin agreed to separate the medical and undergraduate campuses.63

Smith argued before the legislature in favor of Galveston because the Island City possessed size, wealth, opportunity to study diseases, noble citizens, and a school already in operation. Before the medical association he emphasized that students needed a practical education as well as a theoretical one and that such experience could be gained in Galveston as nowhere else. Opponents said, however, that Galveston was vulnerable to hurricanes and yellow fever, and that the so-called Texas Medical College really amounted to very little. In 1880, however, with Smith as the commencement speaker, the small, private college produced eight graduates. The Galveston Daily News boasted that fall, “No city in the south possesses better hospital accommodations or a greater diversity of diseases than Galveston.”64

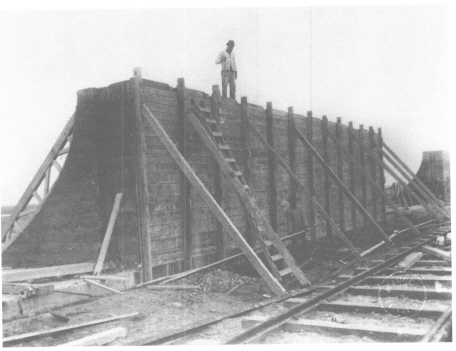

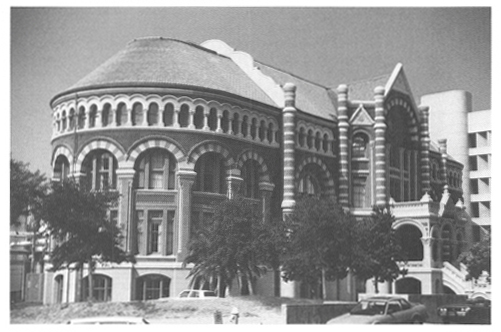

The decision for the location of the state schools was left to the people of Texas, and in October 1881 they voted for separate campuses with the medical division in Galveston.65 In anticipation the Texas Medical College closed, but had to reopen when delays stalled the new facility. Finally, with a bequest of $50,000 from John Sealy, a local businessman, for a new hospital and the donation of a block of land by the city, the new state school began to move. Construction of “Old Red,” the main building designed by Nicholas Clayton, started in 1890; John Sealy Hospital, aided by additional funds from George and Rebecca Sealy, opened the same year; and the medical institution with its new faculty started operation in 1891.66 The school not only trained new doctors, but also contributed thereafter to the health, economy, and society of the island.

Public health and safety were critical issues at the time. The medical college helped, but the main difficulties had to be solved technically in the political arena. The problem was complex and demanded solution if the city was to advance. During periods of epidemic there was always a scurry to clean up the streets and alleys. One question was where to put the garbage and trash. From the earliest time Galveston used a four-footed answer—pigs. Swine have been used as urban scavengers worldwide from ancient times to the present. Hogs eat all sorts of garbage and develop a taste for human excrement. Until 1869, when they were declared a nuisance, pigs roamed free on the streets. An early visitor, Matilda Charlotte Fraser, noticed the work of Galveston hogs and the dogs which tormented them. The pigs lacked tails and ears, but otherwise flourished.67

Garbage was not well handled in the nineteenth century. Citizens were responsible for their own property and depended upon private collectors to haul the trash away. This was done irregularly. People dumped trash, offal, the refuse of outhouses, and slops in back alleys, and the dirt of stores into the front gutters. In 1879 the city provided a trench behind the dunes for garbage and the bodies of animals, and later allowed trash to be dropped in four-foot water off the eastern end of the island. By 1886 the municipality had established a regular dump at 33rd Street and Avenue A.68

The smell of Galveston, especially when the breeze stopped, must have been powerful. In 1868 an editor commented that people passing the fruit, vegetable, and chicken stand on Centre Street had to “grapple their noses” and move at a brisk trot. “Whoever owns the layout should clean it or bury it,” was the conclusion. In 1875 the Galveston Daily News printed an estimate of 875 tons of fecal matter and 2,300,000 gallons of urine produced by the human inhabitants of the island each year. Much of this went into the soil.69 Add to this the animal excrement dumped onto the streets. A normal city horse produced twenty pounds of manure and twenty gallons of urine per day.70 Then there was the problem of the collectors. The product of the privies was placed in barrels, removed at night between 11:00 P.M. and 4:00 A.M., and dumped into the Gulf. The city physician reported in 1887:

The operation of the night carts has been a more difficult matter to control and has constituted one of the most annoying nuisances under the observation of the office. Drunken, careless and refractory scavengers have rendered the passage of these carts through the streets a curse to the residents along their line of march, filling the air with the vilest known stench and leaving an abiding reminder of their presence behind them in the form of a trail of their horrible freight, spilled and splashed from defective covers.71

So much for the good old days. Undoubtedly, the penetrating perfume of the oleander was a blessing.

There could not exist flush toilets in the city until the technical problems of water supply and sewerage were solved. Since Galveston was only a few feet above sea level, and because there was only a small tide, drainage and flushing were problems. Open ditches served the purpose, imperfectly, until the late 1860’s. Then the city began to line some of the ditches with wood. They were supposed to carry away surface water, but they did not work well. Worse, some building owners began to connect toilets to them. When it rained, every street became a pond. “The water seems to run in streams in different directions, regardless of drainage, and when in one place it becomes of sufficient depth, a stream flows away from this as if to aid in filling up some other pond,” wrote the editor of the Galveston Daily News in 1875.72

A system of drainage designed by Pierre G. T. Beauregard in 1873 was not carried out, and the city continued to have problems until the 1890’s. In 1886 the city gave the Galveston Sewer Company the right to lay pipes and charge for connections. By the end of 1893 most of the area between 14th and 27th Streets, the bay and Broadway had been “sewered.”73

There was still the problem of water supply. Water was necessary for drinking, business, and fire control; and the amount captured from rainfall was inadequate. In 1841, for fire protection, the city council appointed wardens for each of the five segments of the city to warn and watch. The first volunteer firefighting company, Hook and Ladder Company No. 1, was formed in 1843. It was followed in the next forty years by others such as the Island City Company No. 2; Old Ax Company; Mechanics No. 6; Young Eagles; Phoenix No. 2; and Protection Fire Company No. 8. They fought blazes, held dances, marched in parades, and raced each other. Part service and part social, they came and went. The city provided some street cisterns, engines, and hose. In 1872 the companies fought nineteen fires, and in 1873 there existed nine units, three steam engines, four hand pumpers, and 348 men. The municipality installed an electric alarm system in 1876 covering a twelve-mile circuit.74

The local board of insurance underwriters, nonetheless, raised the insurance rates 10 percent in 1880 because they thought Galveston only nominally protected. After a $707,000 conflagration on the Strand in 1882, the rate jumped 25 percent, raising a demand for a better water system, organization, and alarm system. The motive, of course, was to reduce insurance rates for business; greater safety was a side issue. The city contracted for a salt-water system which would draw from the bay and pump to 110 hydrants through eight miles of pipes. Although the project, completed in 1884, failed the test of throwing ten streams one hundred feet high at one time, it did wet the top of the seventy-foot Moody Building and scatter the watching crowd when a squirming hose writhed loose from the three men holding it. The city accepted the system.75

After another fire on the Strand, a small one, where “everyone seemed to be boss, and a dozen were calling out orders at one time,” the aldermen in 1885 provided for a professional fire department. The elected chief of the volunteer companies, William Oldenberg, became the head of the new division. In his picture he appears proud of his long, sweeping black mustache, speaking trumpet, white helmet, badge, and vest which did not button easily over his ample stomach. With his new position he received a salary of $1,600. He bought a fancy buggy with striped wheels and an old fire horse released from service in the transition. Most of the time the aged horse moved no faster than a dogtrot, but at the note of a bell from church or railroad he pricked up his ears, lofted his “caudal appendage,” and took off. He dragged the helpless chief along at breakneck speed, and yielded the right-of-way to no person or animal. He halted automatically, however, at every pile of burning trash.76

The department was barely a month and a half old when Galveston’s worst fire struck. It began early in the morning of November 13, 1885, in the business section at a foundry near 17th Street and the Strand. The alarm was slow, and a stiff northeast wind sent a solid sheet of flame across the Strand to wooden frame buildings. A sea of sparks and glowing embers swirled on the high wind currents several blocks ahead and started new fires as they fell on wooden shingles. In five hours the conflagration cut a two-to-four-block charred swath from 16th and Strand to 19th and Avenue O, while thousands of geese, ducks, and seabirds floated high above the burning buildings with their wings illuminated by the red glow. The fire destroyed 568 homes in 42 blocks, and cost $1,500,000.77

Everyone turned out to save household goods. Furniture was moved to the streets, and then had to be moved again as the flames advanced. Much was lost. The population fought back with bucket brigades, wet quilts, and fire equipment, but the salt-water system failed to provide sufficient pressure and two steamers broke down when bits of shell clogged the nozzles. Some reports said that fire hydrants were left running and abandoned, and that hose was burned up. The fire eventually burned itself out, and fortunately no one died.78 In defiance to the destruction, the Galveston Daily News stated:

It is a great calamity. . . . But the driving wheel of Galveston’s existence is unimpaired. The soul of the city is not disturbed. The busy marts of commerce go on as if nothing had happened; the great warehouses and counting-houses are open; the hundred rivulets of commerce and industry that throb and thrill and give life to the community are flowing on. . . .

She will be as beautiful as ever in a few months, and is still doing business at the old stand.79

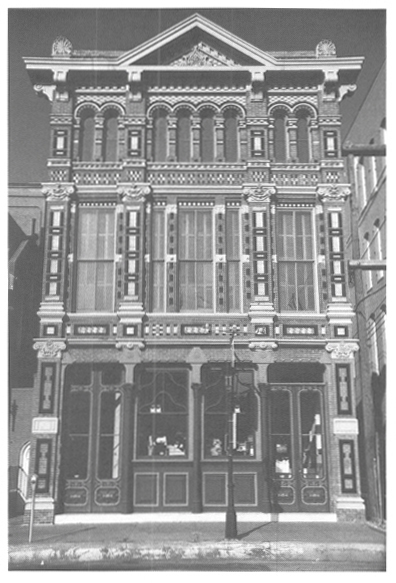

The city government provided $15,000 for relief, the Beach Hotel opened its doors to the homeless, and Mayor Robert L. Fulton confidently announced, “The affluent of Galveston can care for her poor.” With outside donations the relief fund eventually reached $105,000. The city quickly rebuilt, and the officials dictated fireproof material for the business area. Elsewhere people reconstructed their Victorian homes with porches to catch Gulf breezes and intricate figures in black, white, red, blue, orange, and pink colors. The gable and mansard roofs were clothed in fireproof tin, slate, and galvanized shingles.80 It was this phoenix with its ornate plumage which gave the city much of the architecture prized in the 1980’s.

The fire underwriters raised their rates again after this disaster. They liked the fire department—the first professional group in Texas—but condemned the alarm and water systems.81 The alarms could be easily fixed, but the supply of water did not come readily. Water was a major problem affecting not only fire protection, but also public health and the growth of business. The use of rainwater and cisterns did prevent the spread of water-borne cholera, but the amount was limited. There were no springs, nor streams to draw from. Some people used shallow brackish wells for bathing and there was some consideration of using a pond, Sweetwater Lake, down the island for urban supply. Cisterns went dry in 1870 and 1879, and water had to be purchased from peddlers with barrels.82

There was also some talk about using surface water from the mainland, and condensing sea water, but the first serious attempt to solve the problem came with the drilling of deep wells. The technique of using a pointed steel bit attached to an iron rod for driving pipe down had been described by the newspapers in 1857. John P. Davie sank a one-and-one-half-inch pipe to eighty-one feet in 1873, and the C. B. Lee Foundry drove a two-inch pipe to 210 feet two years later. Both wells brought up brackish water. Charleston and Dallas, meanwhile, in the late 1870’s found artesian water with wells.83 Why not Galveston?

An attempt to pound a well 2,250 feet for the city in 1881 ended in “miserable failure” at 765 feet when the pipe telescoped underground. Using a revolving pipe with a toothed rim and water flushing through it, the Santa Fe Railroad six years later drilled to 759 feet and produced sixty-five to seventy thousand gallons per day. The water contained salt, lime, iron, soda, sulphur, and some natural gas. It was unsatisfactory for the railroad’s boilers and later the company let it run into the bay. This deficiency was unclear at first. In the enthusiasm of the quest three other companies drilled and the city placed a contract for a system with thirteen artesian wells placed every 800 feet along Winnie Avenue. When the system was completed in May 1889, Galveston had spent $450,000 for the wells, 17,000 feet of mains, a pump house, and a standpipe.84

Initially, the cost of service to a six-room house with a bathtub and watercloset was $30 per year, plus $1.50 more per thousand feet of lawn. Water rates dropped after this, fire insurance cost declined 25 percent by 1889, and customers improved sanitation with flush toilets. It was a forward step, but the brackish water corroded pipes and produced pinhole leaks in industrial equipment. Water from a three-thousand-foot well proved no better.85 Galveston still needed fresh water.

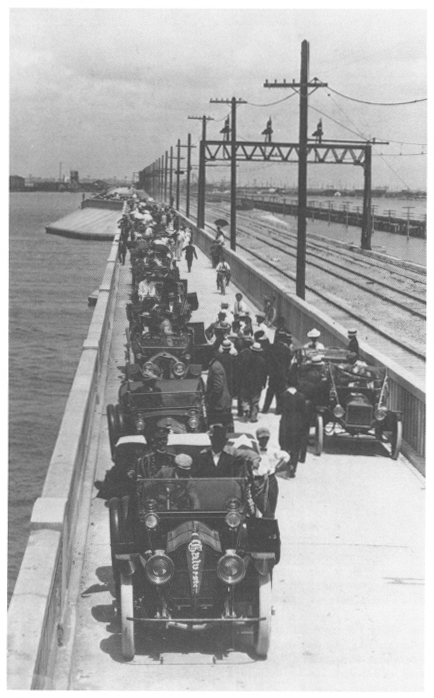

Across the bay in the late 1880’s a Hitchcock rancher, Jacques Tacquard, drilled an artesian well which produced wholesome water. The Santa Fe Railroad also bored a well there in 1887. Following that hint, Galveston officials looked over the nearby mainland and in 1893 found a favorable site seventeen miles from the city at Alta Loma, west of Hitchcock. The civic authorities contracted for thirty wells and a thirty-inch main laid in a trench across the bay twelve feet below low tide. The main connected to the existing system, and pressure within the pipe kept out salt-water contamination. The cost was $780,000, but a large crowd celebrated the completion in 1895 at the Beach Hotel, which provided a fountain of fresh water.86 The exhibition fulfilled a long-standing fantasy.

The basic problem of fresh water was solved. Over time Galveston added chlorine to the supply and began to look for additional surface sources. The water table at Alta Loma slowly dropped, and the water became more saline.87 No city can exist without water, nor can it mature without sufficient supplies for business and sanitation. Galveston, with cost and effort, had solved the problem. It could go on.

In other ways the city progressed. Alfred H. Belo, owner of the Galveston Daily News, visited the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876 and viewed the exhibit of Alexander Graham Bell. He returned home and strung a telephone line between his home and office in 1878. A telephone exchange began service in 1881 and connected to Houston in 1893. A reporter testing the new double copper circuit asked the Houston operator about the weather in the Bayou City. The answer: “Horrid and warm.” In 1899, long-distance lines reached St. Louis, Kansas City, and Chicago—and, through them, the rest of the nation.88

With a champagne toast, the Brush Electric Company in 1882 demonstrated a string of electric lights that turned the street corner at 26th and Postoffice “light as day.” Businesses quickly installed the new technology, and the city established its own electric plant in 1889 for street illumination. Electricity, the new urban power source, was applied to the streetcars in 1891.89

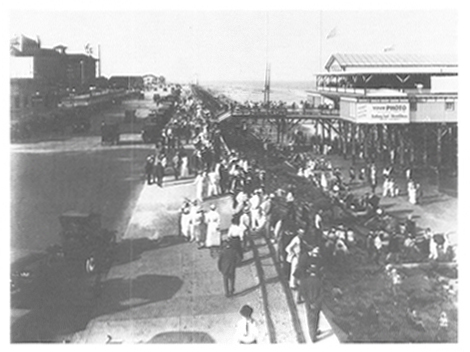

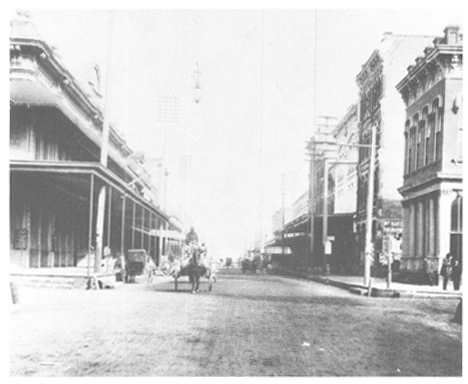

Road conditions also improved. “While other cities complain of mud, Galveston mourns her sand,” wrote the newspaper editor in 1870. “Pedestrianism is toilsome, and riding intolerable. Our citizens once off the business streets wade ankle deep in sand, and experience all the discomfort of ruined shoes, untidy hose, and uncleanliness generally.”90 As a remedy the city shared the cost of oyster shells with property owners. It did not work well, but much of the business area was shelled by 1871, when the city began using wooden blocks bound together with hot tar to pave the Strand. The wood offered a flexible, durable surface which was easy on the horses. It proved to be the pavement of choice for Galveston until the end of the century, even though officials experimented with bricks in the 1890’s.91

Sidewalks before 1873 were much like the streets, and the condition none too good. “Half of the time it is found to be much easier to walk in the middle of a shelled street, despite the danger of life and limb, rather than the abominable sidewalks. We have hardly a decent one in the city,” complained a newsman in 1872. The next year the city government required elevated sidewalks of brick, concrete, or asphalt with curbs of pressed brick. That helped—maybe too much, because the new sidewalks provided attractive pathways for bicycle riders, who developed into a menace for pedestrians.92

Life in the latter part of the nineteenth century in Galveston was rich, full, and varied. With its eastern and European connections, it became the most sophisticated city in Texas. The Island City was the largest for two decades, it was first with urban innovations, and it was the richest. In 1870 there were fifty-eight people in Texas with estates worth $100,000 or more. Eleven of these lived in Galveston County, more than anywhere else. They were all merchants from the city.93

The flow of immigrants through this Texas gateway provided cultural heterogeneity. Four thousand or so per year walked over the docks on their way to somewhere else. In one month, January 1871, 4,673 arrived. Jesse A. Ziegler, who lived in Galveston from 1857 to 1883, remembered standing and watching as the newcomers trudged up the middle of the road to the train depot—Russians in fur coats; Swiss in knee breeches; Scots with bagpipes; women and children burdened with pots, pans, and utensils.94 Czechs on their way to farms in Fayette County began arriving in 1852 and continued to come until the turn of the century. Several poor Norwegian families passed through in 1869 and abandoned two dead children at the train station.95

The most important group were the Germans, who began their migration before the founding of the city and continued it throughout much of the century. They were mainly agricultural people looking to escape European poverty and politics. They influenced Texas culture, and some provided insight about their adopted country. After a forty-four-day passage Emma Altgelt, a twenty-year-old German immigrant on her way to Indianola and the interior of Texas, arrived in Galveston in 1854 and recorded her observations. To her the town looked like paper toys with the houses up on poles ready to be moved one place or another. More impressive, however, was the crowd of German men at the wharf who rushed on board looking for women to marry. She noted a middle-aged baker who spotted a pretty blonde peasant girl and first tried to hire her as a cook. She refused his high wages and said that she was going to her brother who had paid her travel expenses. Desperate, the baker blurted, “I want to marry you right now!” The girl coolly replied, “To be married is exactly what I do not want.” Emma Altgelt liked that answer.96

The Germans who remained on the island founded a Turner Association and military unit, held an annual May Day celebration, and maintained a landscaped park and pavilion called the Garten Verein. It operated in the summer and offered music, food, bowling, and romance. Red-faced German waiters with flowing mustaches served platters of cold meat, salads, and ice cream with glasses of lemonade and steins of beer. “The Wednesday night concerts and picnics have been responsible for more changes of heart in the last twenty years than all the other agencies combined which Cupid has established in Galveston,” remarked a reporter in 1897.97 To honor his parents, Stanley Kempner bought the park in 1923 and presented it as a gift to the city.98

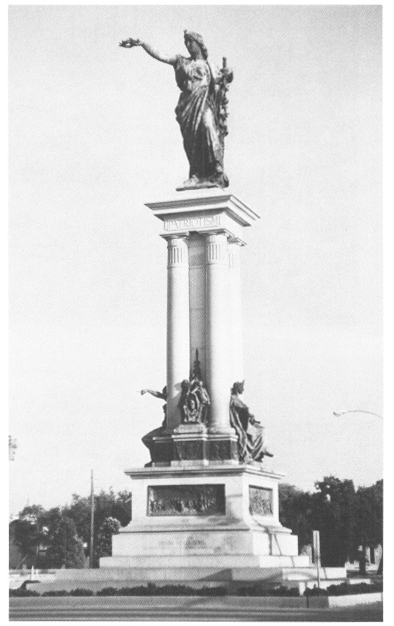

Among the outstanding immigrants was a Swiss named Henry Rosenberg. He arrived in Galveston before the Civil War at age nineteen and proceeded to make a fortune in dry goods and banking. He variously served as an alderman, vestryman for Trinity Episcopal Church, director of the Wharf Company, director of the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railroad, director of Galveston Orphan’s Home, and consul for Switzerland in Galveston. He became one of the early philanthropists in 1888, when he gave $40,000 to the public schools. At his death in 1893, Rosenberg designated a number of bequests, the largest of which was $400,000 for a public library. The most interesting part of his will read, “I give thirty thousand dollars for the creation of not less than ten drinking fountains for man and beast in various portions of the city of Galveston, localities to be selected by my executors.” This portly humanitarian whose statue sits solidly in front of the Rosenberg Library had sympathy for his fellow creatures and took advantage of the city’s new-found water supply. A good man. Seventeen carved marble fountains of varying sizes were installed, but only four, in new locations, survive to the present.

Of greater endurance was his bequest for a statue to the Texas Revolution. It became the city’s landmark. Created by sculptor Louis Amateis, the seventy-four-foot bronze and granite statue features the female form of Victory holding a laurel wreath in outstretched arm pointing toward the San Jacinto Battleground across the bay. Officials placed it in the middle of the intersection at 25th (Rosenberg) and Broadway.99 The irreverent say that the statue gestures not toward the site of Texas independence, but to the location a few blocks away of Galveston’s infamous red-light district. But that is a story from a later era, when Galveston achieved an independence of a different sort.

Enrichment of city life also came from other directions. The Galveston Lyceum presented debates—in March 1868 the debate subject was: which is more happy, an old bachelor or an old maid? The Galveston Historical Society started in 1871. Its purpose was to preserve materials about Texas history. Interest waxed and waned, and finally it ceased meeting in 1931. There was also the Galveston Chess and Whist Club, but most significant was the long success of theater in the city.100

There were theatrical presentations before and after the Civil War, but the man who dominated the latter part of the century was Henry Greenwall. He took over and remodeled the Tremont Opera House at Market and Tremont, and arranged for players to come from New York after the yellow fever epidemic of 1867. The troupe arrived in November, but by error their wardrobes went to Havana. Greenwall opened, nonetheless, on November 21. He scraped by for the next fifteen years or so, and explained to a critic in 1876 why he had to rely on second-rate talent. The top-flight people either would not come to Galveston or demanded three to five thousand dollars per week. That was a fee the city could not support. Interest soared in 1875, at least for five days, while Mme Rentze’s Female Minstrels were in town. The male population from “banker to bootblack” jammed the Opera House to witness the variety show, which included the notorious Can-Can, “a lewd and voluptuous dance, in which a lot of depraved men and women throw themselves into all manner of lascivious motions.” Feeling somewhat ashamed, men in the audience sat low in their seats with coat collars turned up, but the police refused to stop the show. After the group left town, the newspaper said, “It is understood that incense and olive oil will be burned in the Opera House throughout to-day to purify its atmosphere and make it a fit place once more for ladies.”101

During the 1879–1880 season, which lasted from November to April, Galvestonians enjoyed opera, comic opera, troubadors, Buffalo Bill, a wizard, plays, and more minstrels. In 1882, with improved profits, a leading actor, Edwin Booth, presented the most brilliant engagement yet seen in the city. He was followed the next season by Fay Templeton. Booth returned in 1887, and in 1888, the “Jersey Lily,” Lily Langtry, arrived by private railroad car for a performance. Sarah Bernhardt played La Tosca and Camille in 1892 with her fluffy auburn hair, delicate face, and teeth like “rows of pearls.” A dazzled reporter found her handshake firm and her movements “poetry in motion.” “She is rightly called ‘divine,’” he concluded. One of the last plays in the Tremont Opera House was Charley’s Aunt, a “hummer” of a comedy about college boys at Oxford.

Then, on January 3, 1895, Henry Greenwall opened a new theater, the Grand Opera House, a “thespian temple.” It had a carved stone archway and marble tile in the lobby. It boasted a parquet floor, oak seats, boxes, yellow-pine wainscoting, gas and electric lighting, heat, air ventilators, a seventy-five-foot wide by sixty-eight-foot high by sixty-eight-foot deep stage, and a drop curtain featuring Sappho and her companions. Marie Wainwright, daughter of Commander Wainwright of the Harriet Lane and the Battle of Galveston, starred in Daughters of Eve. It was a gala evening in full dress; it was Galveston at its best.102

Galveston at its worst was found in the shadows of the underworld. In a port city with great numbers of transient people, the expectation, tolerance, and opportunity for vice and crime were greater than in other places. Aury and Laffite left that legacy, and a certain disrepute remained a characteristic of Galveston throughout its history. In the nineteenth century the police arrested two to three thousand people per year. Easily the most common crime was drunkenness, followed by fighting and disorderly conduct. A sure way to rouse a fight was to call someone a “damned Yankee.” In the last quarter of the century, after Galveston gained continental railway connections, vagrancy became a popular charge.103

Vagrancy was a convenient reason for the arrest of tramps. These “knights of the road” arrived in the winter months seeking warmth. They were mainly a nuisance. “When they are seen lurking and skulking about places where they can have no possible object or business,” explained a policeman in 1885, “they are hauled up short.” The police herded them on a boxcar, sent them across the bridge, and dumped them out. It was illegal to send them to another town. Most of them followed the track right back to the island.104

The police also used arrests for vagrancy to harass prostitutes. In the boom recovery after the Civil War, with plenty of opportunity and demand, prostitution bloomed as never before. It was in this period that the area about Postoffice, Market, and 26th through 29th Streets developed as a vice district with bawdy houses, saloons, and “variety shows.” The shows, according to the police, were “hotbeds of crime,” but they were legal and given police protection. Captain J. M. Riley explained, “Bear in mind that by varieties shows I mean those places where beer is jerked by women, and the can-can and like performances are given on the stage.” There, young men and boys developed a taste for beer and liquor, and the “nude adornments of the variety stage.”105 They were the nineteenth-century equivalent of a striptease club.

On occasion the activities of the demimonde broke into the newspapers and onto the police records. One man shot another in the mouth over a black harlot, Mollie Harris, in 1867. She had been arrested earlier that month for firing a pistol and using insulting language. Two years later she broke into the brothel of Caroline Riley and attacked another black prostitute, Jane Dickenson. The police arrested six black women in that squabble and charged them with street-walking and vagrancy. It cost them five dollars and court costs except for Riley. As the madam of the house she merited a ten dollar fine. Harris could not pay, so she went to jail for five days. Riley the same year started a three-year term in the penitentiary for accepting stolen goods, but she was back in business at Postoffice and 29th in 1872. The editor of the News shortly noted the numerous complaints of Riley’s bawdy house, where black whores using obscene and profane language often appeared nude on the street. A raid two days later produced fourteen arrests, and a notice to the owner of the building to desist from such use in the future.106

Prostitution was illegal, along with drunkenness, gambling, and carrying dangerous weapons, but there was tolerance of these vices. “They flaunt their ribbons and wriggle their dresses with too much audacity, and ply their vocation with too much boldness,” clucked the Galveston Daily News.107 The police, however, reacted only when there was trouble, and brought “nymphs de pave” into the courts for periodic fines. Neither police nor courts closed the houses of ill fame. The women were simply fined, not too much, and turned loose to continue their business. The vagrancy law thus had the effect of an extralegal occupation tax for the benefit of the city treasury.108

The authorities and society had more important concerns, of course, than to be too upset over “the most ancient and agreeable of all professions,” as a prominent Galvestonian characterized prostitution.109 There were murder cases to be solved. In 1843 Charles Henniker, a German truck farmer, hit his partner with a mallet and dropped him into a well. When the victim tried to climb out, Henniker beat him back with a scantling and held him underwater until he drowned. He then robbed the man and burned his house. A woman exposed Henniker’s guilt and a court condemned him to be hanged “dead as the devil.” The German was a tough character. He rode to his gallows seated on his coffin while smoking a pipe. He threw his last dime into the crowd, rejected a hood, and dropped through the trap. Henniker’s neck did not snap as it was supposed to and he looked out at the spectators with clear, calm eyes while he gently swayed and gradually strangled.110

The most sensational and grisly murder of the century occurred in 1884. According to the first reports, Emil Richard Fleschig, a young recent German immigrant, had committed an “outrage” on the wife of his employer. The husband, Charles Junemann, a dairyman who lived three and a half miles from town, organized a posse which searched without success for the young man. Two days later a farmer driving some hogs noticed flies buzzing in a clump of bushes. Upon looking he found Fleschig, dead, hanging from a low cedar branch with a rope around his neck. Henry Weyer, the local justice of the peace, held an inquest, found no violence, ordered the body buried, and opened a keg of beer for the people there. Fleschig had committed suicide.

That should have been the end of it, but it was not. Rumors circulated. Witnesses said the body appeared in strange condition. Fleschig stood five feet ten inches, or so, and the branch he used to hang himself was only five feet off the ground. The rope was carelessly wrapped around it and the body, on all fours, hung forward with the head only nine to ten inches off the ground. It was skinned up, and one eye protruded. Certainly, a strange suicide. The state forced a second inquest and examination of the corpse. The German society in Galveston offered $100 for information about lynchers.

Time passed, other witnesses spoke up, a trial occurred, and a new story emerged. Fleschig, who spoke little English, had worked for Junemann for about six months, and complained to his friends that he had a hard time obtaining his wages. In addition, Mrs. Junemann abused him, ordered him around, and struck him. Neighbors reported that she had commanded him to bring her water while he was chopping wood. Fleschig refused and she hit him with a billet. She also threw a hatchet at him. He threw it back and hit her in the head. She fell bleeding and young Fleschig, thinking that he had killed her, fled.

A neighbor, summoned by a boy, found Mrs. Junemann sitting in a rocking chair, bleeding from a one-inch head wound. “Emil struck me in the head with a hatchet,” she said, “because I would not sleep with him.” The hunt was on. Five men, including Charles Junemann and Judge Henry Weyer, found the fugitive hiding in a barn. Junemann stole a ten-dollar gold piece from Fleschig. Then, while two of them held the young man, the others choked him, “shoved a stick in his corruption,” and kicked him to death. They tied Junemann’s cow rope around his neck and left the body in the bushes tied to the cedar branch. As it turned out, one of the lynchers was already in jail in Kentucky. Three of them, including the judge, received five-year sentences, and Junemann a two-year term in prison. All were minimal penalties.111

To hold lawbreakers, the county maintained a jail from the start. The brig Elba, beached in the 1837 hurricane, became the first place of incarceration, and Henry Forbes, a black man charged with larceny, was one of the first inmates, in 1840. While the jury was deciding about him, Forbes escaped and was recaptured. Since breaking jail was a capital offense, he was hauled off to the gallows and hanged. En route, he sat on his coffin and sang a hymn at the top of his voice. Most citizens thought the punishment too harsh in this case.112

The county built new jailhouses periodically as the old ones fell apart. In 1866 the jail was so bad they put a twelve-foot wall around it with broken glass at the top. It was unfortunate that insane people often had to live there because of overcrowding in the state institutions. A disturbed woman who raged, cried, and broke everything stayed in the county jail for six months in 1874, to the great annoyance of the neighborhood, until there was room in the Austin asylum. “I don’t mind watchin’ murderers and burglars, but these crazy women are enough to drive a man wild,” commented the keeper. Even in 1898 there were nine insane women and eleven insane men kept in the prison.113 There was not much to be done about it, and it was not unkind. There was just nowhere to send these unfortunate people.

The city supported a paid police force from the beginning, and a saloon owner, Leander H. Westcott, was the first marshall. The department began a night watch in 1857, maintained a curfew over blacks, and offered to whip slaves at the owner’s request for one dollar. During Reconstruction there was difficulty with the quality of appointments to the force, and one chief fraudulently placed extra names on the payroll. In 1869, on the other hand, the division improved by starting the use of photographs to identify criminals.114 As was usual in the century, the main purpose of the police was to protect property by maintaining order.

Elsewhere in Texas the police sympathized with the laboring person and could not be relied upon during strikes. In Galveston this does not seem to have been the case, although in severe instances military units bolstered the police force. Galveston was a major center for union activity. Before the Civil War, lack of industry, sectionalism, ethnic loyalties, and the small number of workers all tended to discourage unionization. Printers on the island, nonetheless, formed the state’s first labor organization, the Typographical Union, in 1857. The carpenters got together in 1860, and after the war they were followed by the brickmasons, black longshoremen, and hack drivers. By 1872 there existed over a dozen unions. The depression of 1873–1876 hurt, but the strikes of 1877 in Galveston and elsewhere heralded the birth of modern labor.115

In the ninety-nine-degree heat of July and August that year, the black wharf workers, followed by black women laundry workers, newspaperboys, and white street laborers struck for better wages. There were some rough encounters, but they were short-lived and little was gained. Draymen, black longshoremen, and streetcar drivers, however, successfully forced higher pay in 1881.116 The Knights of Labor struck against the Santa Fe Railroad in 1885, and in Galveston the affiliated workingmen stopped the trains despite the efforts of police. “Don’t do it, don’t do it,” the unionists chanted as the police-protected strikebreakers tried to fire up a locomotive. The scabs gave up, the engine remained dead, and the Santa Fe complained about the lack of protection.117

In response the county sheriff called out the local military units as a posse comitatus. The Galveston Artillery Company even arrived with two twelve-pound howitzers. “Probably never in the history of Texas has a posse been organized consisting of such wealthy and representative citizens,” commented the paper. The labor crowd greeted them with hisses and jeers, and the good people of Galveston responded with the sound of cocking Winchesters, pistols, and shotguns. The sheriff stepped between the posse and the strikers and asked for peace. It worked, and shortly labor and management began to arbitrate.118

White and black union competition on the Mallory wharf attracted the Knights of Labor again in early November, and the trains stopped once more. This strike lasted but briefly, and again there was arbitration. The result was greater participation by blacks in the labor of the wharves.119 The Pullman Strike of 1894 arrived in Galveston in July, but the mayor with the help of police and militia forces forced the trains through.120 In 1898 the Mallory Company broke the strike of its black union by bringing in scab labor on barges from Houston. Even though the strikebreakers were protected by police and soldiers with Gatling guns, there were three deaths and several beatings.121 Things were getting rougher.

A gentler effort to gain labor equity came from the women of the Galveston Cotton Mill. The mill, located at 40th and Winnie, employed 550 people, used thirty to thirty-five bales of cotton per day, and paid $150,000 in annual wages. Bertrand Adoue, “a monument to Galveston enterprise,” was president, and the board of directors included business leaders such as Julius Runge, Morris Lasker, Leon Blum, and George Sealy. Although it represented a $500,000 investment, the mill was an anachronism. It was constructed in 1889, over a decade after cotton manufacturing in Texas declined.122 It did not last long in Galveston either, but the Galveston Cotton Mill constituted one of the last major attempts to establish an industrial base for the city.

The women of the mill sent a delegation to appeal to the city officials in February 1895. They said that they were working thirteen hours per day with forty-five minutes off for lunch. They had previously worked eleven and a quarter hours per day, but the time had recently been extended. They earned ninety cents per day, but were docked for errors, thus losing five to fifteen cents per day. The mistakes came in the last hours when they were tired and it was dark. There was only one light bulb for every four looms. There were 150 children at work there, and they were slapped and hit by the foremen—Mrs. E. W. Ormond testified that her son bore scars from the ill treatment. The women did not protest the amount of pay, but they did object to the increase in hours. They asked the city fathers to investigate.

One alderman said that he would not work his horse that hard, and the city leaders agreed to arbitrate. The company explained that a sixty-six-hour week was normal—eleven and a quarter hours during the week and nine and a quarter on Saturday. There was a need for overtime, however, because they were testing new looms, and also because they had lost time to cold weather. It was necessary for the mill to work at a sixty-six-hour-per-week pace, and it was customary in the industry for the employees to work extra hours so the mill did not fall behind schedule. They also worked overtime so that they could have Christmas Day free. The city officers failed at arbitration, and the mill won the fight with the use of strikebreakers.

Forty to fifty women returned to the council and requested $1,000 so they could return home. They had been enticed to move to Galveston to work in the mill and now they wanted to leave. The aldermen refused the money, but took up a private collection among themselves amounting to $175.123 There was obviously some sympathy for the women, but the power of government and the sanctity of law was on the side of business and private property. The cause of labor and unions gained but little in the nineteenth century in Galveston, or elsewhere in the United States.