THE GREAT STORM AND THE TECHNOLOGICAL RESPONSE

Chapter Four

When he opened the fourth seal, I heard the voice of the fourth living creature say, “Come!” And I saw, and behold, a pale horse, and its rider’s name was Death . . .

—Revelation 6:7–8 (Holy Bible)

The hurricane which swept in from the Gulf and devastated Galveston on Saturday, September 8, 1900, killed more people than any other natural disaster in the history of the United States. It was the most profound event in the lifetime of the city, and the reaction of the citizens provided one of the strongest statements by American people about humanity’s relationship to the environment. It has been the technological quest of Western civilization to conquer and shape nature for the benefit and comfort of human beings. This basic principle of the culture, heritage of the civilizations of Europe, carried to our shores by immigrants, asserted itself in Galveston in response to the unforgiving devastation of the storm. There, on one of nature’s frontiers, on an edge of time, the survivors utilized their technical ability to pronounce mastery over their hostile surroundings. It is a story of valor.

During its first week of life, the tempest crossed south of Puerto Rico, through the Windward Islands of the West Indies, curved northward over Cuba, and reached the western side of Florida. It returned to the sea and gathered strength as it moved parallel to the coast until it reached Galveston. There it turned northward on September 8. Between noon and 8:30 P.M., when the center passed about thirty miles to the west, the barometer dropped from 29.48 to 28.48 inches. The wind shifted from north to northeast in this time. The anemometer registered 84 miles per hour before it blew down—there were probably gusts of 120 miles per hour. As the hurricane passed, the wind direction changed to east, then southeast, and finally south by midnight. The storm tide pushed inland by the cyclone reached a height of fifteen feet between 8:00 and 9:00 P.M. Waves and spray, of course, bounded much higher. The 125 thirsty refugees in the 130-foot-high Bolivar lighthouse placed a bucket at the top to catch rainwater. They found the captured water salty.1

The wind blew against the tide, which meant that bay water flooded in from the north and storm water from the south. As the wind changed to the south and the surge ended, the bay water was blown back. The flood tide, therefore, fell rapidly after midnight as the storm moved inland across Texas and was gone by morning. The hurricane blustered with reduced strength through Oklahoma and eastern Kansas, reaching Iowa on September 11. It crossed the Great Lakes and Montreal the next day, traveled through the St. Lawrence region, and went back to sea off eastern Canada by September 22. The storm charted a four-thousand-mile path and had enough punch at the end to cause havoc to a French squadron in the Atlantic near Newfoundland.2

No one knows for certain how many people died on Galveston Island and the mainland—probably, 10,000–12,000. The best estimate for Galveston alone is 6,000 deaths. Every year the Morrison and Fourmy Company published a directory of the city. They guessed that twice the number of people listed was an accurate count. In 1900, therefore, they placed the population at 42,210. The U.S. Census figure for that year was 37,789, but Morrison and Fourmy argued that the census was taken in the summer when a lot of people were out of town. In 1901 when the company canvassed the city they calculated a population of 34,086, which meant a loss of 8,124. Considering the estimate that 2,000 had moved away from the city, they concluded that the figure of 6,000 dead was accurate. The Galveston Daily News, on October 7, 1900, listed 4,263 identified dead. The destruction of 3,600 homes, plus commercial damage, meant a $30 million loss.3

Modern sociologists have worked out a model for the study of disasters which includes the following stages: preparation, warning, impact, emergency rescue, short-term recovery, and long-term recovery. They have discovered that in disaster most people do not panic or become hysterical; there is little looting; there is an unusually high level of cooperation; victims often form “emergent” groups to deal with unforeseen problems; and people often do not respond to initial warnings of danger.4 Although developed seventy years later, many of these conclusions apply to the 1900 storm.

After almost a century of experience with hurricanes, it is surprising how little preparation had been made. The city had planted a line of salt cedars on top of the dunes to stabilize them, and had built a wagon bridge as well as three railroad bridges to the mainland. Sand had been hauled into the city to elevate it and promote drainage, but even then the highest point in 1900 was slightly less than nine feet above sea level. Entranced by the “lotus-eater charm” of the island, natives took the presence of hurricanes casually.5

The seafaring community, of course, assimilated traditional folk warnings of bad weather. “Mackerel skies and mare’s tails / Makes lofty ships lower her sails,” and “Red sun in the morning, sailors take warning, / Red sun at night, sailor’s delight.” A halo around the moon, high circling gulls, or a storm bird flying low across the water toward land were all bad signs.6 “Crab Jack” took warning from the crustaceans he tried to catch.

Crabs is mighty queer critters, and the best barometers ye ever seen. When there’s a storm coming crabs goes for deep water and buries ’emselves in the mud, an’ they don’t come back afore the storm’s over, neither. Why, just ’fore the big storm in ’75 I din’t get no crabs, only one er two, and them was all black with mud. I knowed right away there was goin’ ter be a storm, and jest pulled up my nets an’ took my things all ashore. . . . That storm didn’t catch Crab Jack, though—not much. The crabs told him it was comin’, an’ he got out of the way.7

By 1900 there were more scientific methods of prediction. The United States established one of the earliest weather stations in Galveston in 1871. It provided careful barometer readings and wind measurements. The day before the 1900 storm the barometer showed little change, but the resident climatologist, Isaac M. Cline, was suspicious. He had been in Galveston for eleven years and was fascinated by hurricanes. He knew about cyclones in India which pushed huge storm tides ashore and killed thousands of people. He thought such a storm could move right over Galveston Island with equally destructive results.

The weather service informed Cline by telegraph that a hurricane had smashed across Florida and was at sea somewhere between the Galveston and New Orleans weather stations. At midnight September 7 the moon was bright and there was no sign. Perhaps the storm had spent its force in the Gulf? There was only slight wind. The weatherman noticed, however, long swells breaking on the beach with an ominous roar, and a tide rising above normal height. “The storm swells were increasing in magnitude and frequency and were building up a storm tide which told me as plainly as though it was a written message that a great danger was approaching.” By dawn the high tide, some two feet over normal, began creeping over the lower parts of the island. The barometer slowly dropped, and Cline, contrary to department procedures, harnessed a horse to his two-wheeled cart and headed down the beach to warn people to seek high ground. The hurricane flags—two red squares with black squares in the center flown in tandem—were sent whipping in the freshening wind to the top of the flagstaffs. Sometime before the storm reached full fury, men tried to raise the warning atop the Cotton Exchange Building, but the wind had already carried away the pole.8

The warning time was adequate. The fearsome flags were flying all along the Texas Coast and in Galveston. John D. Blagden of the local weather service stuck by the telephone all day to warn the people who called. Even with that, many people went to work and hundreds of others toured the beach to watch the excitement. The city had been through storms before. “Everybody ’round here got so used to de storms dat dey don’ mean nothing,” said Ella Belle Ramsey, a black woman who survived. But this one was different. “’Bout time we got settled de wind come up an’ den de water come,” she continued. “Chile, I can’t tell you how dat water come. It jes come pouring in. Dere wasn’ nothing to stop it den. We wen’ on upstairs ’cause de water come in de downstairs. I was praying to de Lord an’ I never think ’bout nothing else.”9

Even the chief climatologist was fooled. Cline warned the inhabitants within three blocks of the beach to evacuate, but that was not enough. With the storm tide still rising, at mid-afternoon he sent his brother to inform the weather headquarters in Washington, D.C., that Galveston was going under and to request aid. Joseph Cline waded through the streets to the telephone exchange. The wooden block pavement was afloat “like a carpet of corks,” but he was able to get the message through to Houston shortly before the line went dead. With that, the Cline brothers waded to Isaac’s house to wait out the storm.

About fifty people were there, including Isaac Cline’s pregnant wife and children. His home, located four blocks from the beach, had been specially braced to withstand hurricanes, and even the builders took refuge there. The whole town was awash, but the houses on their stilted foundations stood above the waves. Debris, however, piled up around the structures and dammed the water. It poured into Cline’s first floor, and the occupants retreated upstairs. The construction was stout and might have withstood the onslaught, but there was another hazard for which there had been no planning.

The storm uprooted the trestle of the beach streetcar line together with ties, cross pieces, and fifty-foot rails. It moved, lashed, floated, and rolled like Death’s scythe in the fury of the storm. The trestle battered the Cline house, turned it over, and beat it to pieces. Joseph Cline felt the home move, grabbed two of his nieces by the hand, turned his back to a windward window, and smashed through the glass and wooden shutters into the howling wind and rain. They were alone on the side of the overturned house and he shouted back through the window, “Come here! Come here!” There was no response, and as the house disintegrated into the swirling water the three of them moved to the trestle.

Isaac Cline, his wife, and their youngest daughter were in the center of the room when it turned over. They were pinned by wreckage and carried under. Helpless, Cline thought, “I have done all that could have been done in this disaster, the world will know that I did my duty to the last, it is useless to fight for life. I will let the water enter my lungs and pass on.” He lost consciousness. Shortly, however, the timbers lifted him above the surface and he woke up. A flash of lightning revealed his daughter next to him, and he could see his brother with his two other children one hundred feet away. His wife was gone.

They gathered the youngsters in front of them, turned their backs to the wind, and put planks behind them to protect them from flying debris. The slate shingles, so practical against fire, proved lethal while sailing and skimming at a hundred miles per hour in the hurricane wind. At times the brothers were struck so hard they tumbled into the water. They clung to the trestle, listened to the crunch of shattered houses and the screams of the dying, and rescued a seven-year-old girl from the waves. They moved to various pieces of flotsam as necessary and finally grounded on a long line of debris at 28th Street and Avenue P. In its grinding fashion the storm constructed a breakwater of wreckage stretching roughly from the eastern end of the city to 45th Street and parallel to the Gulf about six blocks from the beach. The hurricane destroyed everything outside of this—about one-third of the city, 1,500 acres.

From the debris wall the brothers and four children clambered through the upstairs window of a house and stayed there, huddled with others, for the remainder of the nightmare. They were among the few who escaped the Cline house. Two weeks later searchers working in the planks and timbers at 28th and P found the body of Mrs. Cline. Entangled in the wreckage of her home, underwater, she had traveled with her family to the point where the living found safety. The seven-year-old, Cora Goldbeck, whom the brothers pulled from the water had been visiting her grandparents with her mother. They were all dead, and the Clines promised to care for her. Several weeks after the event, in a drugstore, Joseph Cline met a grief-stricken man from San Antonio who was looking for his lost family. He asked their name, and, happily, Cora was reunited with her father.10

Others experienced their own adventures and tragedies. St. Mary’s Orphanage washed away, and rescue workers found ninety corpses nearby, including a nun with nine children tied to her. The bodies of two sisters showed up at Texas City across the bay, and three boys survived by drifting about on a tree for three days. Henry Ostermeyer, who farmed down the island, survived by clinging to a salt cedar while waves washed over him. The next morning he made a stew from sea gulls and potatoes before walking into town. He lost everything from his farm, but the following May a cow with his brand and a new-born calf were found on one of the small islands in Galveston Bay. They were returned to him.11

John Newman had no place to go for shelter, so he went to a bar. The water rose neck deep and the bartender stood on the counter while serving the customers. “Talk about devotion to duty!” thought Newman. He bought a flask, left, floated about a bit, and arrived at the second-story veranda of a house protected by a brick building. He knocked on a door, and a woman came and asked him what he wanted. “What do I want? What do I look like being in need of?” he retorted. She rented him a bed for thirty cents and he slept for the remainder of the night. The next morning he discovered part of the house missing and the occupants gone. Undisturbed, he found the remains of a store, opened a bottle of beer and a can of sardines, and ate breakfast.12

Sunday morning, the day after the disaster, began with the sound of bells from the ruined Ursuline Convent calling people to worship. There was a brilliant sunrise, clear sky, and calm sea—it was as if nature were embarrassed by what had happened. To Joseph Cline as he climbed from his shelter, “dreadful sights met our gaze on all sides.”13 There was a thirty-block-long line of debris, head high and four to ten feet deep, packed with pieces of houses, branches, sand, household items—the broken remnants of urban life. The previous high-water mark from 1875 was 8.2 feet; in 1900 it was 15.7 feet. Everything—trade goods, household items, machinery—not eight feet above the first floor was water damaged, and the salt water was insidious. Later, startled riders found their bicycles collapsing beneath them, the frames rusted from the inside.14

There had been sixteen ships in the harbor, and they were now scattered and aground. The hurricane stranded the British ship Taunton twenty-two miles away at Cedar Point in Trinity Bay and blew the British steamer Roma sideways down the channel. It took out three bridges. The lightship, moored between the jetties with a 1,500-pound anchor and sixty fathoms of two-inch chain, was pushed four miles across the bay. The telegraph, telephone, and electric lines were down, along with the water pumping station, streetcar line and the trains. Worst of all, bodies, human and animal, everywhere were beginning to rot in the warm, moist sunlight.15

There were a few positive points. The water main under the bay and the Alta Loma facilities survived. Most of the brick buildings, including the hospitals, endured, and injuries were not extensive. It seems that people were either alive and all right, or dead. A railroad bridge, although damaged, remained and could be repaired. The grain elevator was all right and the wharves not too torn up. The jetties suffered a 720-foot breech, but the harbor suffered only minor shoaling on the inner bar. Above all there was a fierce determination by most of the citizens to stay and fight back.16

When Colonel William G. Sterett, one of the most celebrated journalists of the time, came to Galveston for the Dallas Morning News to inquire about the condition of the sister newspaper, he came ashore at the wharf. As he walked across a plank, he looked into the water and saw four or five naked, swollen bodies, floating face up, open-eyed, looking at him. He found the newspaper with its doors broken, flooded, engines and press damaged. He met Major Robert Lowe, the general manager of the Galveston Daily News, and remarked that if he were Lowe he would print the paper in Houston. Lowe exploded, “You would, would you? Well, I won’t,” he exclaimed as he shook his fist and stamped the floor. “You never lived here. You don’t know—and you would ask me to desert? No, no, no! This paper lives or dies with this town. We’ll build it again and The News will help.”17 The newspaper did not miss an issue.

To be sure, people moved from Galveston never to return. Some left later, like Julius Stockfleth, a marine and landscape artist, who lived in Galveston from 1885 to 1907. He was a bachelor who enjoyed his fourteen relatives. Twelve of the family perished in 1900. He retired to his native island of Fohr in the North Sea, where, haunted, he was often observed pacing the seawall when storms approached.18 Most of the population, however, refused to give up. “I shall return to Galveston as soon as the City is in sanitary condition, for to go in its present condition, I would be in the way,” wrote a friend to Rabbi Henry Cohen. “I have not lost faith in Galveston, and am willing to stay with her through thick and thin, for with all her faults and calamities, I love her still, and am anxiously awaiting the time when I can return there.”19

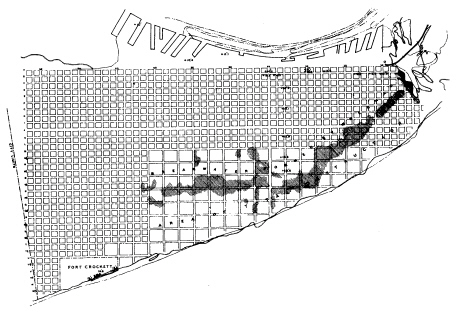

MAP 4. Hurricane Damage, 1900. From Henry M. Robert, “Effect of Storm on Jetties and Main Ship Channel at Galveston, Tex.,” House Documents, 56th Congress, 2d Session, Document 134.

For the immediate future, however, there were immediate problems. What was to be done about restoring the city—water, lights, trash, caring for the injured and destitute, food, clothing, burial, control of sightseers, finance, looting? In many disasters where local officials are incompetent, or nonexistent, an organization emerges to handle the crises. In Galveston the designated leader, Mayor Walter C. Jones, did his job properly and organized the short-run recovery. He called a council meeting at 10:00 A.M. and another at 2:00 P.M. on September 9. He appointed a Central Relief Committee made up of leading citizens and assigned them specific tasks. John Sealy was placed in charge of finances; Ben Levy, burials; W. A. McVitie, relief; Daniel Ripley, hospitals; and Morris Lasker, correspondence. McVitie formed subcommittees for work in each of the twelve wards.20 The government remained in charge of traditional political matters; the new committee took care of the emergency.

The Central Relief Committee decided that every able-bodied man should work on the clean-up squads and that those who did not would not be fed. It also decided that women and children should have preference on outgoing transportation, and that visitors would be restricted unless they were coming to help the city. The committee set up a pass system with guards to check the passes. The isolation of the island helped control the convergence problem, a phenomenon of disasters in which sightseers try to get into the area and victims try to get out. Levy shortly discovered the magnitude of the burial problem and asked Jones for permission to forego formal inquests. The aldermen approved. The bodies were taken care of as quickly as possible and with minimal attempt at identification.21

Six volunteers, meanwhile, crossed the bay on William Moody’s yacht, and reached Texas City. The storm had flooded inland about ten miles, and the couriers walked through a prairie littered with debris and corpses. At the railway they found a handcar and pumped fifteen miles until they met a train to carry them to Houston. The Bayou City and others responded quickly and began sending supplies and volunteer workers by boat and train; the first relief party of 250 men arrived on Monday, September 10.22

Rumors of looting brought out an armed guard of Galvestonians on Monday and Tuesday with permission to shoot on sight. The current story, which was roundly exploited in the national media, held that seventy-five “ghouls” were shot. Clarence Ousley, who was there at the time and later edited a book about the disaster, doubted the figure—there were no records nor proof—and reasoned there were no more than six killed. The Galveston Daily News on September 11 reported eight black looters killed, but two days later verified only seven. The police record for September listed only one arrest for robbing a body and five for looting. The October report noted only one ghoul and one looter.23

There was one dramatic, but questionable, eyewitness. Albert E. Smith went to Galveston to make a film for the Edison Company. He lied to the officials in Houston in order to obtain a pass and also lied to the guard who questioned him on the island. He bribed workers with whiskey to arrange body scenes for the camera and later wrote:

On the following day I was preparing to leave the area when I saw militiamen seize a man as he was hacking off a finger from a cadaver. His pockets were full of fingers, each bearing a ring. I saw the soldiers slip a sugar sack over his head, stand him against one of the funeral pyres, shoot him, then throw his body into the fire.24

Maybe so. On November 30 the newspaper reported forty-five bodies found in a swamp down the island with the pockets turned inside out. In mid-December forty-four more were found with the pockets slit open and no jewelry. On September 30 the police had arrested a man and woman picking up loose items. Their house was filled with all sorts of household furnishings and they claimed that they were going into the second-hand furniture business.25 So, what can be concluded from this evidence? Ousley is probably correct about the executions, and there was probably some looting. People in disaster, however, generally do not act in such a manner; there is a moratorium on crime. By September 13, furthermore, there were two thousand armed police, soldiers, and deputy sheriffs on duty in Galveston. Adjutant-General Thomas Scurry of the Texas militia took over police duties at the request of the mayor on September 13, declared martial law, established a curfew, and closed all the saloons.26 There just was not much opportunity for crime even if there had been the inclination.

The task of body disposal was enough preoccupation for everyone. There is no odor more powerful nor more repulsive than that of a decaying body. The crews worked with handkerchiefs soaked in camphor over their noses, and were given whiskey to ease the gruesome task. Father James M. Kirwin, the local Roman Catholic leader, commented, “It soon became so that men could not handle those bodies without stimulants. I am a strong temperance man . . . but I went to the men who were handling those bodies, and I gave them whisky. It had to be done.”27

Kirwin, who helped direct this task, had trouble getting volunteers, but the police and military units rounded up workers at bayonet point and forced them. At first, the burial details tried to dig trenches for mass disposals, but the ground was so saturated that the holes filled with water. Next, they decided on burial at sea. By Monday evening the crews had collected seven hundred bodies, mostly naked, enough for three barges. A gang of fifty black men were forced on board at gunpoint, and the barges were towed eighteen miles into the Gulf. The corpses had to be weighted and dumped; the next day the barge workers returned, ashen in color. Two days later the body of a woman buried at sea with a two-hundred-pound rock attached to her was discovered on the beach. Others shortly began to float ashore on the west end of the island. Following that grisly episode, workmen burned the bodies where they found them.28

The dead were uncovered at a rate of about seventy per day for at least a month after the storm. A Red Cross woman held the following conversation with a man attending one of the fires:

“Have you burned any bodies here?” I enquired. The custodian regarded me with a stare that plainly said, “Do you think I am doing this for amusement?” and shifted his quid from cheek to cheek before replying.

“Ma’am,” said he. “This ’ere fire’s been goin’ on more’n a month. To my knowledge, upwards of sixty bodies have been burned in it—to say nothin’ of dogs cats, hens, and three cows.”

“What is in there now?” I asked.

“Wa’al,” said he meditatively, “it takes a corpse several days to burn all up. I reckon that’s a couple of dozen of ’em—just bones, you know—down near the bottom. Yesterday we put seven on top of this ’ere pile, and by now they are only what you might call baked. To-day we have been working over there (pointing to other fires a quarter of mile distant), where we found a lot of ’em, ’leven under one house. We have put only two in here to-day. Found ’em just now, right in that puddle.”

“Could you tell me who they are?” I asked.

“Lord! No,” was the answer. “We don’t look at ’em any more’n we have to, else we’d been dead ourselves before to-day. One of these was a colored man. They are all pretty black now; but you can tell ’em by the kinky hair. He had on nothin’ but an undershirt and one shoe. The other was a woman; young, I reckon. ’Tenny rate she was tall and slim and had lots of long brown hair. She wore a blue silk skirt and there was a rope tied around her waist, as if somebody had tried to save her.”

Taking a long pole he prodded an air-hole near the centre of the smouldering heap, from which now issued a frightful smell, that caused a hasty retreat to the windward side. The withdrawal of the pole was followed by a shower of charred bits of bone and singed hair. I picked up a curling yellow lock and wondered, with tears, what mother’s hand had lately caressed it.

“That’s nothin’,” remarked the fireman. “The other day we found part of a brass chandelier, and wound all around it was a perfect mop of long, silky hair—with a piece of skin, big as your two hands, at the end of it. Some woman got tangled up that way in the flood and jest na’cherly scalped.”29

It was a hard situation, but the human fortitude was remarkable. In mid-September, for instance, a gang of black laborers uncovered the body of a small negro. One of the crew identified the body as his own child and broke down in tears. The men shared his grief and offered to bury the body rather than cremate it. The father refused to violate the orders and walked along as his fellows carried it to the bier on a plank. He then turned and went back to work.30

You would think that people would go crazy under such stress, but they did not. There is only one example. A man went insane the day after the storm and had to be lodged in jail. Most persons responded in a rational manner, as people have in other disasters. One man explained to a reporter how he reacted when his house washed away: “How did I feel? I was not excited. I was not in fear of my life. There was a restless, uneasy feeling among us all, but actually no fear.”31 At the Ursuline Convent, where a thousand people, black and white, took refuge, the blacks began singing in camp-meeting fashion after the north wall fell. The mother superior rang the chapel bell to quiet them and announced that the convent was no place for such scenes. If they wished to pray, she said, they should do so silently, from the heart. She then offered baptism to all who desired it. People there did not panic. They rescued others floating by, and one woman gave birth in a nun’s cell.32

The days passed, and at night observers on the mainland could see the long line of cremation fires glowing in the darkness across the water. There were no vultures in Galveston, and the pyres burned into November. By mid-December only skeletons turned up. They found the last one on February 10, 1901, ten miles down the island, a fourteen-year-old girl.33 Meanwhile, the city had begun to recover. In the first week the telegraph and water supply were restored. During the second week workmen cleared most of the streets and alleys, began to lay underground telephone lines, and restored the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railroad bridge. All the rail companies shared the bridge, and the first train arrived September 22. That was the same day General Scurry revoked martial law. In the third week the Houston relief groups returned home, the saloons reopened, the electric trolley began operating, and freight started moving through the harbor. On October 14 one of the largest shipments of cotton, 30,300 bales, cleared the port.34

During a sidewalk conversation about the future of Galveston, Joseph Cline commented, “Commerce always takes precedence over life,”35 and, indeed, business quickly reasserted itself. Henry M. Trueheart, who ran a real estate firm and managed property, sent the following form letter to his customers:

Many thanks for your sympathy. All of us and our families safe, except our Mr. Minor [Lucian Minor, an employee], lost in endeavoring to save others. We are all cleaning up and repairing buildings fast as possible. We are cast down, but not destroyed, nor discouraged. Loss of life and property not exaggerated. Your papers safe.36

Trueheart explained to a client in Colorado Springs that Galveston property had devalued by one-third, and that Trueheart intended to operate on that basis even though the tax assessor wanted to keep last year’s rates.37 To D. C. Jenkins of Los Angeles, Trueheart wrote about the house he had been trying to sell:

Until yesterday we were unable to examine your house, and we found it in the following condition: forty-two panes of glass out, back stairs in dangerous condition, plastering in very bad condition, many of the shingles off the roof, kitchen down and card posted on it condemning it; stable all to pieces and some of the fences.38

Before the hurricane the top offer had been $3,000; afterward the best was $1,000. That news must have made the Los Angeles man rather unhappy with the turn of events.

For much of the population there was nothing left, and no insurance. Outside aid was necessary, and initially stores and restaurants fed people from their supplies free of charge. The city organized relief stations in the wards, and hundreds, mainly women and children, traveled to Houston for emergency shelter and aid. For several months the railroads gave victims free passage anywhere in the nation, and there was no lack of employment.39 The city paid $1.50 to $2.00 per day plus food and housing. The commissaries gave free supplies to those with no money for ten days, and afterward to those who could not work.40 Clara Barton and the Red Cross appeared somewhat late, September 17, expecting to find a large number of orphans. There were not that many, and they had been absorbed already by other institutions in Texas. Barton, nonetheless, appealed nationwide for donations: “. . . if you can believe me, your country woman, I am here and my fingers are in the wound, and I assure you that the side was pierced and the nails did go through.”41

The Red Cross competed with the ward commissaries, so the city simply turned relief work over to Barton and her retinue. She organized a subsidiary group for the black community, dispersed $17,341 in contributions, and gave away piles of clothing. People were generous in some instances, such as the seventeen-year-old New England girl who sent a satchel with three good suits and all accessories for someone her age. Others sent bedraggled finery, crushed bonnets, soiled work clothing, 144 left shoes, ragged shirts and towels from a city laundry. The Red Cross women sifted through the assorted boxes, gave away the good items, and placed the trash in barrels outside on the street. They did not want the bad publicity of burning clothes. In the morning the containers were empty. The organization tactfully bought some items from local merchants and left Galveston on November 14.42

The Central Relief Committee continued to operate a commissary at the turn of the year, and the editor of the News warned about creating a permanent pauper class. Some 450 families, 1,700 people, were drawing supplies. The commissary closed the second week in February with a rush of 150 uncontrolled people who helped themselves and cleaned out the shelves.43 The committee also dispersed money directly to institutions and individuals, built 1,432 water closets and cesspools, gave away 222 Singer sewing machines, provided money for 1,114 building repairs at an average of $106 each, and constructed 483 three-room cottages at a cost of $300 each.44

The committee received $1,258,000 in donations from around the world. New York State with $94,000 gave the most—a bazaar at the Waldorf-Astoria netted $50,000.45 After six months no one depended upon relief, commerce had revived, and the stricken population possessed the necessities for living. It was a remarkable recovery carried out with efficiency. On Sepember 8, 1901, seven thousand people attended a memorial service at Lucas Terrace near the beach, where two hundred had sought shelter from the great storm and twenty-three survived. They planted salt cedars and oleanders, and the following day threw garlands into the placid waters of the Gulf.46

It was well to remember, and grieve, but what of the future, the long run? The vulnerability of the island was now plain to almost everyone. No one could forget. What could be done to make it safe? Who would pay for it? After the hurricanes of 1886 there had been discussion about building a seawall and raising the elevation of the city to prevent flooding. There was insufficient interest to carry out the ideas then, but at least the thought was there. Shortly after the great storm in 1900 the ideas revived. In late October Henry M. Robert, one of the Army engineers who had recommended Galveston as a deep-water port, met with civic leaders and discussed the future. The subject of a seawall came up, but there were no definite plans expressed. Robert was of the opinion that the storm was unique and that Galveston should go forward.47

Then a surprise occurred. The Fort Worth Board of Trade called a convention in late November to discuss the needs of Galveston. There, representatives from the old Deep Water Committee presented a program: replace the current city government with a commission appointed by the governor, exempt the city from state and county taxes for two years, refinance the bonded debt at a lower rate, and pass a local tax to raise the grade level.48 This was the opening salvo in an attempt by the power elite to take over the municipal government.

The Deep Water Committee had not disbanded after obtaining federal support for the building of the jetties, but had continued as an ad hoc group promoting the commerce of the island. It was in their self-interest to do so. Members of the committee and their associates directed the eight local banks, dominated 62 percent of the corporate capital, and controlled 75 percent of the valuable real estate. Morris Lasker, John Sealy, Isaac H. Kempner, and Bertrand Adoue provided a link between the DWC and the Central Relief Committee. Kempner was also the city treasurer.49 The DWC accused the city government of incompetence and used the hurricane as a mask to take over. The motive is not entirely clear. Mayor Jones and the aldermen, however, came from a lower class, and the committee did not trust them with the fate of Galveston. After the take-over, members of the DWC rarely ran for office, but they continued to control Galveston’s direction until 1917.50

Within days after the storm, R. Waverly Smith, Walter Gresham, and Farrell D. Minor of the Deep Water Committee began working on a new form of government. They were aware of the commissions used in Washington, D.C., in Memphis in 1878 during a yellow fever epidemic, and for ruling subsidiary divisions of government such as police and fire departments. The Central Relief Committee, moreover, gave them a local example of elites appointed to positions of political power. What they developed was a plan by which the governor of the state would appoint a mayor-president and four commissioners—for finance and revenue, police and fire, waterworks and sewerage, streets and public improvements.51

The plan was obviously undemocratic, and had to be modified later so that the commissioners were subject to election. It also turned out to be rather inefficient. Each commissioner was selected in his own right, with a combination of legislative and executive authority in his own area, and with little inclination to cooperate with others. In America the commission plan flourished during the progressive period before World War I, but then gave way to the city-manager plan. In Galveston it placed the elite in temporary control to carry out their plans for long-range recovery of the city and protection of their economic base.

In order to discredit the old government, the Deep Water Committee claimed that “past extravagance and carelessness” had brought the city to bankruptcy. Change was a matter of “civic life and death,” they said. Every two years the municipality had to pay off its floating debt with a bond issue, because it was impossible to pay the debt with current taxes. Governor Joseph D. Sayers said he would refuse state aid to such a place, and, therefore, something had to be done.52 It was basically an argument of fiscal irresponsibility.

The propaganda was largely false and opportunistic, but with a blush of truth. An independent audit of the city books in 1895 revealed that no trial balance had been taken since 1891. The official accountant did not know how to keep books, and there were many irregularities. Wealthy citizens, and some aldermen, chose to ignore their taxes in these circumstances. There was no fraud, just procrastination, laxity, and error. Mayor Ashley W. Fly had to ask the legislature to permit a bond issue of $200,000 to pay off the floating debt in 1895. He then discovered that it was not enough and asked for another $200,000 in 1897. Walter C. Jones, who had been chief of police, then defeated Fly in 1899.53

Jones reduced the city budget both in 1899 and in 1900, sold city securities above par value, and avoided default on bond payments or salaries in spite of the crises created by the hurricane.54 In December 1900, however, after the fight opened with the Deep Water Committee, he had a problem collecting taxes. The city auditor considered it a “combination, or conspiracy of certain parties who refuse to pay” in order to embarrass the government.55 The auditor did not accuse anyone directly, but the DWC possessed that kind of power.

There were public meetings about the proposed change in government, but the members of the DWC appealed directly to the legislature for a charter change without a vote of the citizens. The newspapers took the side of the committee, and Jones ceased talking to reporters. In his annual address to the city council, however, he said:

While conceding to everyone honesty of purpose and patriotic motives, it is a matter of sincere regret to all lovers of a republican form of government that among our citizens are a number, who boldly organized into a committee for that purpose, seek before the Legislature to discredit our citizenship and submit to the world that we are incapable of self government without the consent of the governed in the form of a commission, in the selection of which not a citizen of this city would have a voice. . . .

By a concert of action they have withheld their just obligations to the government at a time when patriotism would seem to have indicated an opposite course and attempted to place the city in an attitude of a bankrupt municipality until at last, forced by public opinion and the strong arm of the law, a majority have become conscience-stricken, to use a mild term, and paid their taxes.56

The Galveston Daily News labeled Jones’ statement “demagogism” and said he was appealing to class differences.57 It is more likely that the mayor and the city auditor spoke the truth. There is little evidence of fiscal incompetence. Considering the crisis of the hurricane, his defense of democracy, the success of the short-run recovery, and the fact that the newspapers were against him, Mayor Walter C. Jones was one of the unsung heroes of the great storm. Galveston was fortunate to have him, even if he was not one of the elite.

The Deep Water Committee, of course, won. The legislature approved the new charter after amending it to require the election of two commissioners. In the September 1901 election the two candidates of the City Club, a political party backed by the elite, won overwhelmingly. There was no class antagonism, no split in society. The DWC had chosen its time well. During emergencies such as that of the great storm, communities pull together and differences between groups diminish in the face of the common peril. Kempner called it the “Galveston spirit.” This commonality helped gain approval of the commission government, and Galvestonians pioneered a new form of municipal rule which lasted, for them, until 1960.58

The governor designated Judge William T. Austin, one of the elected commissioners, as the mayor-president. The other commissioners were Isaac H. Kempner, finance and revenue; A. P. Norman, police and fire; Herman C. Lange, waterworks and sewerage; and Valery Austin, streets and public improvements. Facing court questions over constitutionality, the legislature amended the charter in 1903 to require election of all commissioners. Mayor Jones took the transition in good grace. At his last meeting he said to Judge Austin, “In presenting you this gavel, I want to express my best wishes for your administration and hope that it will lead to the upbuilding of Galveston.”59

One of the earliest actions of the new government was to appoint a committee to select engineers to devise a plan for protecting the city. The commissioners were thinking about a simple breakwater, but their action was significant. Throughout the country at this time, civic leaders turned to technology to solve problems. Few communities had the severe difficulties of Galveston, but most reacted the same way—they turned to engineers. This professional group stayed in close contact across international borders through journals and organizations. There was a free flow of information, and engineers were among the chief purveyors of technology. The commissioners also broke the old attitude of government strictly as an agent for business. In Galveston as elsewhere there emerged concern for the greater welfare of the populace. In the face of hurricane destruction there was little choice but to act for the benefit of all if the city were to survive. Social concern, however, was a part of massive change in the United States wrought by the progressive movement, the social gospel, and the rise of unions.60

It is interesting that not all Galveston leaders made this transition. In one of the often repeated stories about Colonel William L. Moody and the 1900 storm, his son asked him what they would do about their business if people abandoned the city. “We both like to fish and hunt,” the old man replied. “If they do abandon the city, remember the fewer the people, the better the fishing.”61 There is wit in the reply, but also cynicism. When Galveston could not market its bonds to pay for storm protection, all the local banks responded generously, except the Moody bank, which subscribed for only a nominal amount after the bonds were almost gone.62 The Moody family did not make the transition to social responsibility until the end of the second generation.

Upon the recommendation of the special committee, the commissioners appointed three engineers: Henry M. Robert, Alfred Noble, and H. C. Ripley. Robert, who became the spokesman of the group, had recently retired from the Army Corps of Engineers, had been instrumental in the deepening of the Galveston harbor, and was famous as the author of Robert’s Rules of Order. Twenty-five years before, while a young soldier in California, he had witnessed the tyranny of a presiding officer in public discussion. “I made the rules for the people, rather than for officers. The people have their rights if this is a self-government, and should not be subject to the whim or caprice of any chairman or presiding officer,” he related.63 This famous book became the law for the running of democratic bodies throughout the world. Robert also knew something about ruling nature.

Alfred Noble, an engineer from Chicago, had been in charge of the harbor and locks at Sault Ste. Marie, built a bridge across the Mississippi at Memphis, constructed a breakwater at Chicago, helped in the grade raising of the Windy City, and worked on the problem of a canal across Nicaragua. H. C. Ripley had been a member of the Corp of Engineers at Galveston and designed the wagon bridge for the city. They were paid $1,500 each plus expenses, and they reported in two months.64

In an hour-long presentation the engineers recommended a three-mile wall of solid concrete, paved on top, from the south jetty, across the eastern edge of the city, and down the beach. To prevent flooding in the city, the elevation of the land would be raised to eighteen feet at the wall and then decrease at an angle of one foot every 1,500 feet to the bay. The engineers estimated a total cost of $3,505,040.65

The city leaders accepted the recommendation without question. Their problem was financing. In December 1901 the new commissioners allowed a $17,500 default on 1881 forty-year bonds. This may have been a ploy to convince New York bondholders to lower the interest rate. The nonpayment was not too much—the old government after the storm had paid out $160,000 in interest and retired another $40,000 of debt. Negotiations in New York resulted in lowering the interest rate from 5 percent to 2.5 for five years. This saved the city $100,000.66

The default, however, made it impossible to sell additional Galveston bonds, necessary for the seawall and grade elevation. Isaac Kempner suggested a meeting with the county officials to ask the county to issue the bonds. After all, the city paid 85–90 percent of the county taxes. The county agreed to construct the seawall and called for a vote to authorize for a $1,500,000 issue. Before the vote, individuals, banks, unions, companies, and other groups came forward to pledge purchase. Eighty-four percent was subscribed before the county electorate went to the polls. The count was 3,119 in favor, 22 against, and 98 percent of the voters responded.67

For grade raising, the city turned to the state for help. There was initial resistance to a relief bill based upon past dislike of Galveston, and Isaac Kempner related how he learned to lobby during this period. He and other Galvestonians made rational but self-seeking appeals for support before the State Democratic Executive Committee with no response. Jens Moller, another lobbyist, then set up a special room to entertain the SDEC and found the politicians susceptible to champagne. There, one of the upstate members of the committee explained to Kempner that Galveston tactics reminded him of two girls sitting on a river bank with their fishing poles dipped in the water. Two boys passed by and one asked, “What luck?” A girl responded, “We have caught no fish, no men.” The boy replied in explanation, “You are sitting on your bait.” After that Kempner argued before the legislative people that the whole state would benefit from the recovery of Galveston.68

The legislature at first provided aid by permitting the city to keep its state taxes for two years. In 1903 the state passed a bill allowing Galveston to sell $2 million in 5 percent bonds, and retain the state ad valorum tax, 75 percent of the occupation taxes, and all of the poll taxes from the county to help pay for them. The law ran for fifteen years, but later the legislature extended it to forty years. The tax allowances paid about one-third the cost of the bonds.69

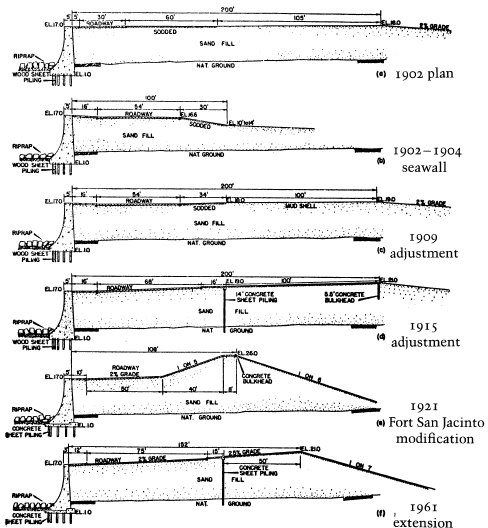

With the financing arranged, the county contracted with J. M. O’Rourke and Company of Denver to build the seawall. It was the first job for O’Rourke with his new partner, George Steinmetz, but both had prior construction experience. They moved to the island, bought machinery in Chicago, and laid a cornerstone in February 1903. Along the site they excavated three feet deep and sixteen feet wide and drove pine piles forty to fifty feet deep. These were protected from undermining with sheet piling—one foot planking—driven down twenty-four feet. Using forty men, the contractors built the wall in sixty-foot sections by pouring concrete into molds over the top ends of the piling with steel reinforcement rods every three feet. Since it took seven days for the cement to set, the workers put down seven alternate sections. They then returned, poured the sections in the gaps, and linked them together with tongue-in-groove joints. The wall was fifteen feet thick at the base, five feet thick at the top, seventeen feet high, and weighed forty thousand pounds per foot. Toward the sea it presented a concave face so that the force of the waves was driven upward, and in front, to protect the toe from washing, it had twenty-seven feet of four-foot-square granite blocks.70

The U.S. Army, which had established a post along the beach front in 1897, Fort Crockett, also planned a protective wall. Since there would be a six-block gap between the county segment and the fort, the county bought the land and gave it to the Army, thereby expanding the base by twenty-five acres. In return, the Army agreed to fill in the gap and extend the wall to 53rd Street. When completed, the seawall connected with the south jetty at 8th Street and Avenue A, angled to 6th and Market, followed 6th to Broadway, angled again from Broadway to the beach, and then out the beach to 53rd.71

In conjunction with the county, the federal government in the 1920’s extended the wall from the curve at Broadway out the beach to the south jetty in order to protect another military installation. This permitted filling the land on the eastern portion of the island beyond the old wall. In 1927 the county lengthened the western end to 61st Street, and in 1951 began a further extension. It took eleven years to complete the new effort due to problems in funding. When finished in July 1962, the wall was 10.4 miles long, one-third of the Gulf coastline. The total cost was $14,479,000.72

During construction in the early part of the century it became popular to “promenade” atop the unfinished seawall, especially on Sunday. Boys set up ladders and charged five cents to use them. One opportunistic group of men and women used a ladder while the owner’s back was turned, but the boy charged them to get down. A reporter commented that this form of enterprise would give Galveston a reputation for “bleeding its excursionists.”73

Women and girls, for the most part, would not go onto the wall because they would have had to climb a ladder. In a day when ladies wore full skirts and the glimpse of an ankle was a thrill for men, ladders were a risqué business. Yet thousands of females wished to inspect “their” wall, and not all were forestalled. A reporter observed an intrepid “Miss Girl” who scrambled up a short ladder and hoisted herself three more feet to the top of the wall while she thought no one was looking. Then a band of boys saw “Miss Girl” at the same time she saw them. They all rushed for the ladder, but the boys reached it first and offered to hold it steady while she came down. “There is one thing a girl will not do. She will not climb a ladder while a boy is down below holding it.” Undaunted, she raced along the wall for three hundred feet and jumped off into a pile of sand. None of the boys would have jumped from that height. She landed on her feet, “kissed her hand” to the disappointed gang, and disappeared down a side street.74

FIGURE 3: Seawall Construction Plans. Source: Albert B. Davis, Galveston’s Bulwark against the Sea (Galveston: U.S. Army Engineering Department, 1961).

In 1904, when the contractors completed the city portion, ten thousand persons attended a dedication of granite monuments to the effort. The work was done on schedule and within $326 of the contract amount. Among others, J. M. O’Rourke, one of the partners who built the $1,250,000 project, was asked to speak. He commented simply, “I will not say anything for the wall, for if it ever has an opportunity you will find it well able to talk for itself.”75 And so it did, in 1915.

The original plan called for paving the top. During construction it became obvious that a walkway should be there also. With a 150-foot right-of-way there was plenty of room. In 1911 Governor Oscar B. Colquitt led in the first car to travel the entire Seawall Boulevard from the south jetty to 53rd Street.76 Thus opened one of the most impressive marine drives in the world.

It took longer to raise the grade of the city, and the technology needed for this task was less known. Engineers knew how to lift houses and buildings. You could do that with hundreds of jackscrews moving a quarter-inch at a time. It had been done in Chicago; Alfred Noble knew about that. The problem was finding and transporting sufficient fill material, and P. C. Goedhart, a Dusseldorf engineer, had the answer. He joined with a New York engineer, Lindon W. Bates, and proposed to take sand from the channel in the harbor with self-loading hopper dredges, move the dredges through a canal cut into the city, and discharge the fluid sand through pipes onto the land. The water would drain away and the sand would remain. The elevation would increase and the channel would be deeper.

It was a unique solution and Goedhart and Bates received a contract to supply 11 million cubic yards of fill in three years. The city agreed to pay $1,938,000, and the county added another $142,000.77 Filling was accomplished in quarter-mile-square sections. Each area was enclosed in a dike, and then all structures, sewers, water mains, and gas lines were lifted. Owners had to arrange for jacking up their houses, but the city paid for the grade raising. While the company pumped in the sand, people learned to walk on planks and trestles eight to ten feet in the air. Individuals even jacked up gravestones and tried to save the trees. Most of the trees perished, however, and fresh landscaping with topsoil from the mainland was necessary. Workers raised 2,156 structures of various kinds, including the three-thousand-ton St. Patrick’s Church, which they uplifted five feet with seven hundred jackscrews without interrupting services.78

The grade raising took longer than expected because of unpredicted problems. The canal, two hundred feet wide, twenty feet deep, and two miles long, shoaled periodically and was too small for the largest dredges. It ran parallel to the seawall from the jetty to 21st, then along P-1/2 to 33rd, where there was a turning basin. Homes along the way had to be removed, and then returned when the filling was complete. There was difficulty between Goedhart and his partner, and toward the end, in 1910, the North American Dredging Company took over the contract and pumped sand from Offatt’s Bayou. Goedhart and Bates lost $400,000 on the contract, but won the praise of the Grade Raising Board. When the work was over in 1911, five hundred blocks had been filled with 16,300,000 cubic yards of sand spread as thin as a few inches to as thick as eleven feet. In later years further filling occurred.79

Although it was not mentioned at first in conjunction with the seawall and grade raising, Galveston required a third major piece of engineering technology for storm protection—a weatherproof bridge to the mainland. In addition to trains and wagons, two new kinds of transportation, automobiles and the electric interurban railroad, demanded attention. Seth Mabry Morris of the medical school reputedly owned the first automobile in Galveston, a 1902 Olds, and the first advertisements appeared in 1903. Despite the fact that drivers were limited to the island, cars became popular. Said Moritz O. Kopperl, the leading enthusiast, “This makes no difference to me, because I can find plenty of sport driving in town and on the beach with my car.”80 Excursions to San Luis, racing over the sand, and a maiden trip to Houston in 1909 enhanced the growing love affair with the automobile. By the end of 1909 Galveston had three garages and 145 cars on the streets.81

The city imposed driving on the right hand side of the road in 1907, license plates in 1908, a ten-mile-per-hour speed limit in 1910, and head and tail lights in 1911.82 Regulations helped, but the impact of the new upon the old was not always pleasant. The newspaper recorded the adventure of a man driving a pony and gig into town on 51st Street in 1915. The pony had never met a car, but he did this day—an automobile without a muffler, snorting and puffing. The pony jumped, jerked loose one rein, dumped the gig over, bolted, dragged and destroyed the equipment, escaped, and left for home on fast-flying, stumpy legs. The driver of the car went over to the driver of the gig as he was getting up unhurt and dusting himself off. “What’s the matter, your horse afraid of the car?” “Oh, no,” was the reply, “not in the least. He’s a circus horse and I’ve taught him to do that.” Then he charged the auto driver fifty dollars for admission to the circus. The amount was paid.83

In 1917 the county replaced its mules and wagons with motor trucks, which were cheaper to maintain, and as the cars replaced horses, a new folklore emerged. Judge O. B. Wigley remarked that a speedometer was unnecessary for the Model T. At ten miles per hour the lamps rattled, at twenty miles per hour the fenders rattled, at thirty miles per hour the windshield rattled, and faster than that, your bones rattled. There was also the story around Galveston about a man who had torn a piece of leaky tin from his roof and sent it to the Ford Motor Company. He shortly received a letter: “Your car is one of the worst wrecks that we have ever seen, but we’ll fix it for you in a week or two.”84

Just as people had sometimes accidentally driven their horses and wagons off the end of a wharf, similar incidents happened with cars and the seawall. In 1918 Mrs. Frank Briggs steered her one-month-old auto to the seawall with her two children and nursemaid and tried to park. She could not find neutral, and the car eased forward at slow speed. The occupants leaped free while the car nosed over the edge, rolled down the concave face of the wall, and turned over with its wheels spinning in the air. In the future others, usually at higher speeds, were to imitate Mrs. Briggs’ unfortunate example. In her case the outcome was not too bad. Bystanders turned the car upright, and it was driven off under its own power.85

Other artifacts of auto culture began to appear: the first traffic signal, at 23rd Street and Seawall Boulevard, in 1924; a bus system in 1936; parking meters in 1939; one-way streets in 1951; and police radar in 1955.86 Throughout this automotive popularity there was a demand for better roads in city and county, and, of course, a bridge to the mainland.

There was talk of restoring the wagon bridge shortly after its destruction in 1900. The railroads, which were sharing the restored Santa Fe bridge, resisted in order to avoid competition from automobiles and the proposed interurban railway to Houston. The Texas Railroad Commission condemned the wooden trestle and ordered the railroads to construct a causeway within reasonable time. The county voters approved a tax levy to help pay for construction and officials called upon Henry M. Robert to review the plans. Fires on the trestle and delays of passenger trains, meanwhile, caused increasing irritation, while the railroad representatives bickered over construction details. A blaze in June 1906 burned 357 feet of the bridge and required a bucket brigade from the city to extinguish it. Fifteen months later, in September 1907, an oil line broke on an engine and soaked the track and ties. Fire burst out under the dead locomotive and moved toward the oil tender. There were two hundred passengers on board, and there might have occurred a disaster. Another train, however, came up from behind and pulled the stranded cars out of harm’s way.87

It was finally agreed that the rail companies would pay 50 percent of the bridge’s construction cost, the county 25 percent, and the interurban line 25 percent. Santa Fe tore down the old trestle as part of the agreement. The causeway, following the example of a viaduct along the Florida Keys, utilized twenty-eight concrete arches with seventy-foot spans. In the center a rolling lift gave a one-hundred-foot stretch for boats to pass through. In order to save money, the roadway approaches on the ends, foolishly, were made from earth.88

The bridge accommodated two railroads, the interurban rails, a thirty-inch water main for Galveston, and a nineteen-foot roadbed for cars. It stood seventeen feet above the water, cost $1,329,000, and was designed to “bid defiance to wind, wave and fire.”89 The Galveston-Houston Electric Railway, the interurban, offered service to the Bayou City every hour from 6:00 A.M. to 11:00 P.M. for $2.00 round trip or $1.25 one way. Travel time was one hour and nineteen minutes, which made it the fastest interurban in the United States in the 1920’s. Stone and Webster Engineering Corporation of Boston built it and operated it throughout its lifetime from 1911 to 1936.90 For twenty-five years the interurban brought the two cities closer together and promoted Galveston as a tourist area for Houston.

When the causeway opened in 1912, Governor Colquitt led a line of 1,500 cars and broke a ribbon at the drawbridge. It was a great day celebrated with blowing whistles, fireworks, speeches, and a dance at the Galvez Hotel.91 Federal money financed another causeway just for automobiles in 1935. It opened in 1938, but a three-and-a-half-fold increase in traffic made a third causeway necessary by 1956. Arched seventy-two feet above the water to avoid the need for a drawbridge, the new one opened in 1961. The old auto causeway was then remodeled and raised to match the new one. It reopened in 1964.92

Thus, twelve years after the great storm, the people of Galveston had completed a massive seawall, raised the level of the city, and strengthened transportation links with the mainland. They had used engineering technology and great amounts of money to accomplish security from the onslaughts of nature. They were confident in what had been done, and it was time for a test.

A preliminary review came in 1909. Although the weather service received advisories from the central office in Washington, D.C., starting on July 18, these were not passed on to the people of Galveston until the storm flags went up at 7:15 A.M. July 21. At 9:00 A.M. the halyards parted, and by 10:40 A.M. the wind was blowing at sixty-eight miles per hour. For the most part, the city was unwarned. On the north jetty thirty-eight people, thinking to get an early start on fishing, had spent the night at Bettison’s Fishing Pier. They woke at 4:30 A.M. with twenty-foot waves and a boiling sea rocking the pier. The sailors of the pilot boat Texas spotted a distress flag and came within two hundred feet of the swaying resort. Two deckhands launched a yawl and rowed through the waves five times. They rescued thirty-two people, and then the pier collapsed, throwing the remaining six into the water. The yawl picked up four of them and the Texas reached the other two. The deckhands, Charles W. Hansen and Klaus L. Larsen, later received the Carnegie Medal for Heroism for their bravery. The pilot ship was not so lucky at the Tarpon Fishing Pier. It could not get close enough and four people drowned, including the circulation manager of the Galveston Tribune.93

At Galveston, men and women went to the seawall to watch the storm and to witness the performance of their handiwork. It was a success. Altogether, only five people died, and the tempest inflicted $99,000 in damages. Galveston sent out the news that it was all right, and there was a feeling that the seawall had proven its mettle.94 A greater test was yet to come.

There was ample warning for the hurricane of 1915. It was first noticed by the weathermen 2,500 miles southeast of Galveston on August 10, and the local weather officer began informing shippers at that time. On August 14 the barometer began to fall and the sea started to flow in long, heavy swells counter to the prevailing wind. Mare’s tails streaked the sky and the wind rose with a dull whir. White pockets of rain splattered the houses as the storm came ashore on the evening of August 16, with its center fifty miles to the west. The barometer dropped to 28.63 inches, compared to 28.48 inches in 1900, but the tide was three inches higher and the wind velocity about the same. Although it lasted twice as long, the 1915 hurricane was comparable in severity to the one of 1900.95

By August 15 it was clear that it would strike the island, and people were told to stay behind the seawall. Hundreds left by train, and there was plenty of time to reach shelter. The last interurban train to leave was crammed with people and their pets, including chickens. Since he was loaded to capacity, the conductor did not intend to take on any more, but at Texas City the passengers opened the windows and a crowd of refugees scrambled aboard. The conductor did not bother to collect fares, but headed for Houston and noticed another interurban train moving in the opposite direction across the ill-fated causeway.96

The cyclone caught the three-masted schooner Allison Doura 137 miles from Mobile and hurled it across the Gulf. Captain Evans Wood ran before the storm with a full staysail until the wind ripped it away. He then left the masts bare, set out drag anchors, and scudded along among waves higher than the ship. He and the crew had no idea where they were when the vessel hurtled over the top of the Galveston seawall at Fort Crockett. The anchors caught in the toe of the wall and, held by the lines, the ship was battered to pieces by the wind and waves on the land side of the seawall. Tangled in the wreckage, his right leg broken and his neck caught on the top part of a shed, Wood began to strangle. Luckily, soldiers stationed at Fort Crockett saw the wreck and rushed to the rescue. All hands, including the captain, escaped death. The storm scattered the cargo, 709 bales of sisal for Mexico, for three hundred yards, and left the broken bow of the ship at 31st Street and the seawall.97

Others were not so fortunate. Falling wires cut the power and halted the interurban car from Houston with sixteen passengers aboard at the drawbridge in the middle of the causeway. They got out and walked back to the Causeway Inn at Virginia Point, where sixty people took refuge. When water threatened the inn some of them, groping in the water for the rails, crawled back to the railroad blockhouse. The inn washed away at 2:00 A.M. and fifteen people there died in the water. The two-story concrete house of the bridge tender protected the ten persons who sought its shelter, even though waves broke into the second story, twenty-seven feet above the normal surface of the bay. In the bay the U.S. dredge boat Houston sank two miles from Texas City, and as it settled the forty-two crew members clambered into the wet rigging. The dredge turned over, and only seven men survived.98

At the Galvez Hotel on the beach behind the seawall the orchestra played for twelve hours, and the assistant manager claimed that “many women were prevented from growing almost hysterical by incessant dancing.”99 Nellie Watson, a nurse in training at John Sealy Hospital, wrote to her friend Golda Willis, a nurse who was away at the time, about the evening in the nurses’ quarters:

From the very first poor Bing was scared witless. Her poor little eyes stared out of her head in a way that made one believe she was going blank wild any minute . . . I felt very uncomfortable myself.

I did let Bing sleep that night as long as she could. She woke in about two hours and got up too. Everybody on the first floor except Wag and Collie sat up, but they slept on. Excitement is simply not in Collie’s bones. While everybody was perfectly frantic, she was lanking around in her usual manner, talking about hot water being in the cold water faucet.

The wind was so strong we couldn’t stand up. We could see that the water was rising and great sheets and clouds of spray were blowing inland. The Gulf was beginning to sound so angry and the wind seemed to be getting worse. We went in and sat still and waited.100

The hurricane which continued into the following day blew out the windows at the nurses’ building and flooded the first floor. When the wind abated the nurses waded to work and spent their time dipping and mopping.101 The storm demolished 90 percent of the buildings outside the seawall and at Bolivar. The bathhouses were gone and riprap boulders had been lofted on top of the seawall. The fifteen-ton granite monument dedicating the wall had tumbled across the boulevard, and at Fort Crockett there was a two-foot nick at the top of the wall where the Allison Doura came ashore. Water washing over the wall took out the pavement from 11th to 19th Streets, and there was minor scouring under the toe. The seawall, otherwise, withstood the test in superb fashion, and protected the city from the battering of the waves. As engineer O’Rourke had predicted, the wall spoke for itself when the time came.102

Water, however, covered the downtown section five to six feet deep, and the wind took out the telephone and telegraph service. Worse, the hurricane washed away the earthen approaches to the causeway and broke the water main. The concrete arches endured well, however, and pointed the way for reconstruction. Every ship in the harbor suffered damage, but the jetties were intact. At Galveston 8 people died, but elsewhere in the storm 304 lost their lives.103

In ten days the streetcars were running, electricity was back, and a temporary water supply line had been put together on the damaged causeway. The city hauled off more than a thousand wagonloads of debris, but there was almost no crime, no cases of looting, and only a few arrests for vagrancy. Business recovered, but the Galveston Pirates of the Texas League had to give up their winning baseball season because the team lost its stadium. Trains began running again in early September, and five ships badly aground were refloated early the next month. Two of them were lodged over four miles from deep water, and workers had to dig a canal to free them. Salt spray and flooding severely damaged foliage, and replanting was necessary. Estimated total property loss was between $4 million and $5 million.104

Compared to the horrendous loss of life in 1900, the injury of 1915 was minimal. Engineers repaired the causeway by adding more concrete arches for the approaches, and the legislature extended the tax-rebate support used earlier to help Galveston in its task.105 The protective devices were a success. Flooding, to be sure, caused damage, but the grade raising and seawall kept the storm loss at a bearable level. As an editor wrote, “If the seawall had not stood, it would have been folly to have urged the expenditure of more money in the effort to make the city proof against damage from storm.”106 The effort, in other words, gave to Galveston the chance to continue as a city.

In the years to come the engineering accomplishments of the early century—seawall, grade raising, causeway—insured the city’s survival. Other hurricanes came to Galveston: in 1919, 1932, 1941, 1943, 1949, 1957, 1961 (Carla), and 1983 (Alicia). There was plenty of warning for Carla, which hit with eighty-mile-per-hour winds and a nine-foot tide. It was not as severe as the storms of 1900 and 1915, but it did contain a surprise. A man on the fifth floor of the Jean Lafitte Hotel called the radio station in the midst of the storm to say that something with the noise of a train and spraying gravel on his window had just gone by. This was one of four tornadoes spawned by the hurricane. It touched first at the seawall at the location of the Pleasure Pier, skipped, and then ripped through twenty blocks along 23rd Street. It destroyed 120 buildings and killed six people. The Courthouse, Ursuline Academy, and City Auditorium suffered severe damage. Estimated total loss from Carla was $15 million to $18 million.107

Hurricane Alicia in 1983 killed no one at Galveston, but left an estimated $300 million in property damages. It will be, after all is settled, one of the most expensive hurricanes in history. Down the island where Alicia’s twelve-foot tides and 102-mile-per-hour winds washed away fifty to two hundred feet of beach, private property holders suddenly found their damaged houses standing on public land. The beach belongs to the people, and now the beach had moved to their front door. The storm, thus, left a legal question in its wake that remains, as of 1985, unresolved.108 There can be only one outcome, however, if freedom of the beaches is to remain. For private property holders this is part of the risk of building in an area where nature is still at work deciding the dominance of land and water.

Human technology made it possible, however, for the city of Galveston to remain on such unstable land. The city did not flourish. Houston, the nemesis to the north, left the Island City far behind in the race for population, wealth, and power. Galveston simply survived. The public defenses against nature came at high cost, but they succeeded for the most part. Hurricanes still caused damage, but Galveston was not quite so dangerous for human existence. Its struggle for survival against nature through the application of technology represents the strongest tradition of Western civilization. Galveston’s response to the great storm of 1900 was its finest hour, and demonstrated that rationality and determination can prevail. This is the lesson that Galveston teaches all visitors who come to the edge of time, stand on the seawall, and gaze in wonder upon the vastness of the sea.