The Paleolithic age has attracted the attention of ecological theorists in recent decades. Some of their interest can be explained by nostalgia for a time that appears unequivocal, clear, and simple as we look backward from our troubled present. But there is much more to be learned from even a short look. The ecological sophistication of both Neanderthals and the anatomically modern humans that gradually supplanted them is striking. Even more striking is early humans’ artwork. In sculpture and especially in cave painting, people chronicled and celebrated the biological world that sustained them. Not only were they capable of deriving a living from a precarious environment, they were able to represent the natural world they experienced and describe how their human community fit into it. Of all the lessons to be learned from the epochs that preceded our own, an appreciation of earlier people’s ability to assess and express their place in nature is perhaps the most valuable of all.

In 1856 quarrymen in the limestone hills east of Düsseldorf, Germany, discovered part of the skull, the thick ribs, and some heavy long bones of what they thought was a bear. The skeleton soon came to the attention of local scientists who recognized it as human; they identified the remains as those of a deformed soldier from the era of the Napoleonic Wars. A leading anatomist, Rudolph Virchow, saw in the bones the thickenings and distortions symptomatic of rickets and osteoporosis. In 1863, four years after Darwin published his Origin of Species, anatomist William King declared that the skeleton was not that of a diseased modern human at all but evidence of a new species, to which he gave the biological name Homo neanderthalensis.1 From the start, the newly named hominid species, Neanderthal Man, created terrible problems. Darwin had refused to speculate on human evolution in Origin of Species, but his account of the historical development, progressive differentiation, and frequent extinction of life forms made the existence and subsequent disappearance of hominid species a clear possibility. Fearing a hostile reaction to his work because of these implications, Darwin had delayed publishing Origin of Species for more than a decade.2 As Darwin had feared, readers immediately realized that his theory opened the door to human evolution, and the great Oxford debate of 1860 between Darwin’s self-appointed advocate, Thomas Henry Huxley—who became known as Darwin’s Bulldog—and the lord bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilber-force, focused on this issue.3

The discovery of Homo neanderthalensis raised the question of the species’ origin and fate and its links to anatomically modern humans. In the nineteenth century, the answer to that question was unequivocal. Scientists and laypeople alike tended to identify evolution with the idea of progress, a link that Darwin himself found unpersuasive. By the logic of progress, hominids of the past must necessarily have been less competitive and less competent than those who replaced them. In our era, when the idea of progress has lessened its grip, the genetic profile of the Neanderthals has been repeatedly probed to assess potential links. Applying newly discovered techniques of DNA analysis to genetic material unexpectedly preserved in bones from the original site, scientists in 1997 concluded that Neanderthals and modern humans last shared a common ancestor five hundred thousand to seven hundred thousand years ago. That dating and the general conclusion of this pioneering study have been reinforced by ambitious surveys that promise to describe the entire Neanderthal genome. But the case is by no means settled; research and speculation continue to keep Neanderthal genetics a hot topic.4

About half a million years ago Neanderthals migrated to Europe either through southwest Asia, where they also have a long history, or, less likely, but still a tantalizing possibility, across the Straits of Gibraltar, which would have been periodically narrowed by glacially induced drops in sea level.5 For the entire course of their history as Europeans, Neanderthals were shaped by advancing and receding ice. During the past five hundred thousand years, ice ages have ebbed and flowed in cycles of about one hundred thousand years. As each cold period reached its maximum in extent and intensity, the polar ice cap surged deep into the European continent. Not only the Neanderthals but every living organism was forced south into frigid but ice-free lands along the Mediterranean coast. Species found refuge from the ice in the Iberian Peninsula, in Italy, and in the Balkans. At the end of each glaciation, as the ice barrier receded, the distant offspring of those who had fled to the south generations before re-colonized a continent wiped almost clean of life.

Cold climate survival put selective pressure on the Neanderthals, favoring individuals whose short stature and compact frames made them better able to retain body heat. Presumably, too, though this is less often discussed, coping with repeated and dramatic changes in habitat put a premium on individuals with inventiveness and dexterity.6 Successfully harvesting animals, turning their hides into clothing, and crafting useful tools are skills that the Neanderthals developed and maintained with little variation over unimaginable stretches of time. They also buried their dead and in some cases buried objects along with the bodies; a few corpses were colored with red ochre, a natural dye.7 Pollen residue in a Neanderthal burial in Iraq suggested to some archaeologists that the dead might sometimes have been strewn with flowers. A second Iraqi burial revealed that Neanderthals cared for their sick and wounded. There is also some evidence that they built fires inside caves in primitive hearths.8

Every prehistoric culture is represented archaeologically by its repertoire of tools and tool-making techniques. The French archaeologist Nicholas Mahudel first proposed differentiating early societies in this way in the early eighteenth century; a hundred years later, in the 1820s, Christian Jurgensen Thomsen classified exhibits at what became the Danish National Museum using similar techniques. Every ancient culture could in theory be represented in many other ways as well, but the durability of stone ensures it a disproportionate place in the archaeological record. Only in rare instances are organic materials like hides, wood, and plant fiber preserved. Pollen, which is remarkably enduring, has only recently been recovered and studied. Typical Neanderthal sites are rich in animal and human bones, in stone tools, and in the litter of stone fragments struck off in the tool-making process.

There is great controversy among experts about the kind and level of intellectual and social life that sustained this toolmaking. We might imagine a flint knapper planning to make a certain tool. He shuffles around the bone-littered cave floor looking for the perfect nodule of flint but fails to find it. Suddenly he remembers an outcropping with just the right quality of flint laced through it. He packs a lunch, grabs a spear, and heads out on a hundred-mile round trip. This sequence of actions, which could be taken for granted in modern humans, requires imagination, planning, organization of behavior, and spatial memory that many archaeologists are hesitant to ascribe to hominids like the Neanderthal. Trade might also account for the long-distance transport of high-quality stone, but trade also seems unlikely among a group that is generally believed to have been incapable of language or intricate social organization and interaction.

Whatever their social and intellectual abilities might have been, in their choice of home sites the Neanderthals showed a high level of insight and intelligence. Preserved sites show a preference for river valleys, and shelters with a commanding view of the surrounding countryside. These locations gave Neanderthals access to water and the prey that water attracts. They also chose sites where supplies of flint or chert were abundant. The archaeological evidence suggests that they preferred south-facing caves sheltered from the north wind and heated by the sun. Many of the caves that they occupied over thousands of years passed into the hands of the anatomically modern humans who followed.

From their choice of shelters, their tools, and from the evidence of their hunting and scavenging, it is possible to draw a picture of the Neanderthal in the landscape. In the typical museum installation, we see hairy creatures none too clean, draped with skins and looking slightly unfocused. In a tableau at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History they are grouped in a cave looking at the burial of one of their fellows in the floor beneath them. If we imagine the same beings standing outside this crude domestic setting and looking over the landscape that they hunted and foraged in, the picture changes dramatically. If a species’ success is measured by survival and adaptability, then the Neanderthals were a great success. They endured in an unstable landscape that recurrently became too harsh to sustain any form of life. Furthermore, they survived for hundreds of thousands of years without disfiguring or destroying their environment. From a technological point of view they were primitive; from an ecological point of view they were exemplary. The environmental activist Dave Foreman made this point in a striking way: “Unlike our own bull-in-the-china-shop kind, there is no evidence that Neanderthals ever got out of balance, ever upset their environment, ever forgot their place in nature, ever caused the extinction of other species.” Perhaps, he speculates, “Neanderthal genes were picked up thirty millennia ago by the Cro-Magnon gene pool … thereupon to drift along beneath the surface, bubbling up now and then in a Lao Tsu, a Saint Francis … a Thoreau, a Muir … a Rachel Carson.”9

Our species, Homo sapiens, began arriving in southwest Asia about seventy thousand years ago. By about forty thousand years ago modern humans were in Europe. After tens of thousands of years of technological inertia, Neanderthals suddenly began to work antlers and bones, materials that they had always discarded unshaped in the past. Among the objects they crafted from the newly adopted material were needles, which suggest a revolution in the way their clothes were made. They began to collect seashells, too, perhaps to wear in necklaces or bracelets.

The anatomically modern humans who moved into the old Neanderthal territories in Spain and southern France were given the name Cro-Magnons by Edouard Lartet and his son Louis.10 Details of the living patterns of these people emerged from excavation after excavation. When they first entered the region, they produced a characteristic set of material remains. This initial culture shared many characteristics with Neanderthal tools.11

Did the newcomers learn their technologies from the Neanderthals, or is the reverse true? If there had been more dynamism in the Neanderthal tradition, it would seem more likely that the new arrivals learned from the old hands. With some flint-working techniques this must have been the case. But since the Neanderthals had never before shown any interest in bone tools and little, if any, in personal adornment (aside perhaps from red ochre), the influence seems to have come from the opposite direction as well. Since Cro-Magnon people often moved into Neanderthal caves, they must have gained insight from their predecessors into proven ways to use local resources. The sum of the evidence suggests that each group learned from the other. Sharing requires a period of coexistence, and the archaeological record suggests that this period of coexistence was in some areas extremely long. The odds are that anatomically modern humans and Neanderthals overlapped in parts of their home territories for up to ten thousand years. That is five times the interval that separates us today from the reign of the Roman emperor Augustus. Whatever ultimately brought the Neanderthals to extinction, it does not appear to have been contact with modern humans.12

Even during the earliest incursions into Europe, Cro-Magnons seem most dissimilar from their new Neanderthal neighbors in their cultivation and preservation of what is useless. Beads and marine shells, brought in over long distances in some cases, are among the most characteristic finds in Cro-Magnon sites. A fragment of bone with deeply etched images of two female deer, discovered in the mid-1830s, is one of the earliest such finds that still survives. As this object and the many similar, though undatable, finds that joined it over the next forty years or so were to demonstrate, the Cro-Magnon people, unlike the Neanderthals, not only collected trinkets but created images of the world around them. Cro-Magnons embellished utilitarian objects like spear throwers with sculptures of animals. They created small animal images and statues with no link to any tool. Cave painting, their most ambitious and exciting art, was not happened on till the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

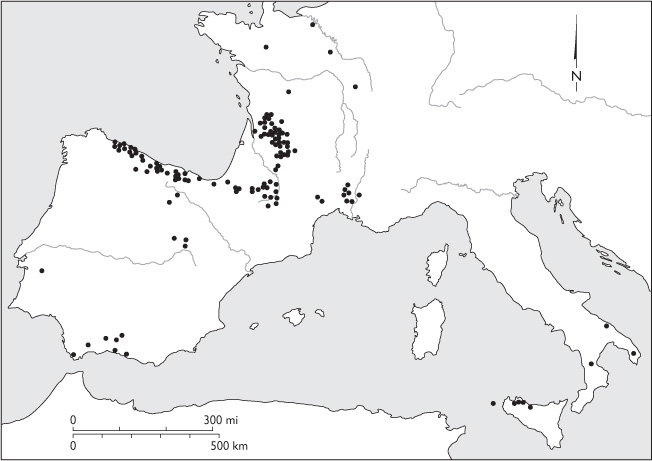

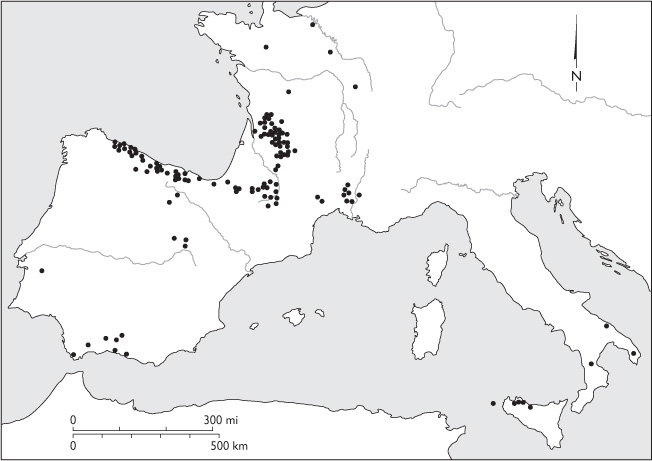

More than any of their other arts, cave painting gives us insight into the way that anatomically modern humans understood the world around them. From their widespread paintings of herd animals and predators, we gain a sense of their close observation and evident reverence for the creatures that sustained them. The first prehistoric cave paintings were recognized in 1879.13 Additional caves were discovered throughout southern France and northeastern Spain. Over the years, many other painted caves have been found in a broad arc that extends from the Iberian Peninsula almost to the Urals. Nearly half of those caves are in France. The Abbé Henri Breuil, the great synthesizer of cave art, identified six caves as having special importance.14

Painted caves dating to the Paleolithic are located throughout northeastern Spain and southern France.

Recent discoveries have added to this master list. The Chauvet Cave, near Pont d’Arc on the Ardèche River, was first visited in 1995. It became the subject of a feature film in 2011. Unlike many other caves discovered by amateurs, the Chauvet Cave was immediately recognized as a site of extraordinary importance, and from the moment of discovery every effort was made to protect it. Walls richly decorated with paintings of a kind not found elsewhere are the most compelling feature of the site, but the cave offers other extraordinary things. Some of the working materials of the artists are still in place. A cave bear’s skull set on a rock and two bear femurs thrust into the mud remain where they were put millennia ago. Probably the most evocative feature of the cave is the many footprints preserved on its floors. The path traced by an adolescent who visited the site can be followed across the hardened clay. To make sure that he or she could find the way back out of the cave, the child made soot marks with a torch on the ceiling. The carbon in these smudges has been dated to twenty-six thousand years ago. A wolf on a similar path may have come through at roughly the same time. The wolf’s prints are unusual. Its middle toes are shortened like those of a domestic dog. If the child and the wolf passed through together, that would be evidence for domestication of the dog twelve thousand years earlier than is generally accepted.15

The paintings in the Chauvet Cave have been dated to thirty-two thousand years before the present. This makes them the oldest cave paintings found in Europe. When the child passed through twenty-six thousand years ago, the paintings were already an incredible six thousand years old. In many ways they are unique, but in others they resemble work that other cave painters created ten–twenty thousand years later. The cultural tradition of the Neanderthals stretched over a period of hundreds of thousands of years. The time scale of the Cro-Magnon way of life was accelerated by a factor of ten. Still, the endurance of cultural practices and the pace of change are glacial by contemporary standards.

Painters in the Chauvet Cave used red ochre pigment or charcoal to create their images. The clay has traces of branches and twigs they dragged inside. They made fires in hollows where cave bears had curled up or among stones stacked against the walls of cave chambers. The fires warmed and illuminated the work area and provided drawing materials at the same time. Whether in ochre or charcoal, the drawings all appear to date from the same time. The wild animals that these early artists painted include species that remained staples of cave art for millennia, as well as images of creatures that were seldom depicted again.

Among the most typical images at Chauvet are wild horses, reindeer, red deer, bison, and mammoths. The atypical images include two strange stylized representations that look like abstract versions of a butterfly and a beetle. There are sixty-five representations of rhinoceroses, three times the total found in all other caves combined. There are even more images of cave lions. The ibex, rare elsewhere, is also well represented at Chauvet, along with a spotted cat and other indeterminate animals. The outlines of human hands created by spraying red ochre are common; otherwise, the human image is virtually absent, as in most painted caves.

Whether common or rare, the animals depicted share several characteristics. The drawings or etchings are generally free and fluid. In most cases the animals are defined by the particular curves of their spines and the graphically simplified details of their heads and mouths. Legs are less often represented. The impression a viewer gains is that all these animals were observed and remembered by people who looked at them from a slight elevation as the animals stood or crouched in vegetation that obscured their lower bodies. The animals are sometimes depicted alone, but more often in groups or pairs. They are usually drawn about half life-size on cave walls at about head height.16

Among the most evocative features of the cave are the massing of figures in groups and the artists’ imaginative response to the cave contours. Irregularities in the wall surface must have suggested to the painter the beginnings of some images. A mastodon in one of the chambers is drawn on a stalagmite with a humpback contour and columnar forms like legs or a trunk. In many cases, the animals seem to emerge from cracks or curves in the walls.

The most unusual and puzzling image is painted on a rock pendant. The centerpiece of the image is the pubic triangle of a woman, an abstraction found etched or drawn elsewhere in the cave. The inner curve of thighs appears to be traced below it. A human figure emerges from one of these thighs topped by a human torso. The armless torso ends in a bull’s head shaded in black and drawn in profile. The bull’s bright white eye seems to stare straight toward the viewer. Beyond this composite figure is a cave lion walking away but looking back. The apparently human trunk and legs with a bull’s head attached is unique not only as a representation of the human figure but also as an assemblage of body parts that do not cohere in nature. The singularity of this minotaur-like creature has led investigators to call it a shaman.

The drawings in Chauvet Cave pose the questions that cave art has raised from the start—namely, Who was it for? What purposes did it serve? Explanations range from the literal to the symbolic. For literalists, the cave paintings of animals represented targets. The primitive hunter threw spears at the representations in preparation for the real hunt. Some painted animals bear marks like those that a spear might make, but the overwhelming majority do not. A more common explanation is symbolic. The paintings, especially those in the deepest and most inaccessible areas of caves, represented shrines associated with hunting. Here the magic of the hunt was prepared through some unknown ritual action. Related to this hypothesis is a second one with broader implications: identifying the decorated caves as the retreat of hunter groups, societies of men who performed secret rituals associated not just with hunting but with the cohesion of the band and the ritual mustering in of adolescent recruits. The shaman figure and the pubic triangle certainly lend support to the idea that ritual played a part in the use of the caves. The links between a hunting cult, a shaman figure, and a symbol of fecundity are also attested in widespread sites.17

Two common assumptions run through all these theories. Analysts have always seen the caves as the analogues of shrines or temples, and all their theories suggest that the sites were visited repeatedly and used systematically. Most assume that the sites were reserved for hunters, who they assume were adult men. Neither of these conjectures is supported by the little secondary evidence that survives. Indeed, the few places where footprints and traces of visitors have been preserved suggest a different scenario. Typically, as at Chauvet, the paintings were created within a short period of time, then abandoned and ignored. Subsequent visits to the cave were few and far between, probably the result of accident rather than design. Perhaps most surprising of all, the footprints preserved in cave floors are disproportionately those of children and adolescents.

Perhaps it is not using the art but creating the art that was most significant to the cave painters. For us, it may be more valuable to ask why the paintings were made rather than how they were used. Art in some form is nearly universal among known human populations of the past and the present. Art concerns itself with such matters of biological significance as reproduction, death, and health. Arts like dance and music play a role in organizing and coordinating group activities. Children make and enjoy art.18

Based on these fundamental characteristics, a philosopher of aesthetics, Ellen Dissanayake, has proposed a theory about the origins of art that takes into account its long history and near universality but focuses on an artist’s ability to create works that are “meaningful, valuable or compelling.” Artists, she writes, “simplify or formalize, repeat (sometimes with variation), exaggerate, and elaborate in both space and time for the purpose of attracting attention and provoking and manipulating emotional response.”19

The context in which Dissanayake sees these patterns on display in their most widespread and influential form is in the special language of words and gestures that parents use when they talk to babies. In her view, “talking to babies, who have innate linguistic capacity, but no acquired language, calls on all the techniques that artists use to make their art meaningful and arresting. Baby talk is simplified and repetitious; it features exaggerated stresses and uncommon rhythms; it is accompanied by exaggerated facial gestures.”20

The instinct to create art is as characteristic of our species as toolmaking, language use, or symbolic behavior. “This universal ability or proclivity is to recognize that some things are ‘special’ and even more to make things special—that is to treat them as different from the everyday.”21

Throughout this book the view of art that Dissanayake pioneered is taken for granted. Art, whether in the form of sculpture, painting, epic, or hymn, is assumed to call attention through formal techniques to the things that matter. For many of us today, bewildered or alienated by the art of our own era, this is not an easy assumption to make. For whatever reason, modern artists appear to have withdrawn from the world as most of us experience it into a private realm with little observable connection to those things that matter most. The crisis that art is experiencing today should not blind us to the ability of art historically to represent fundamental truths.

Following Dissanayake’s lead, we can see that cave art represents a simplified and abstract world in which everything has been reduced to the animals that sustain human life and those that threaten it. Survival depends on complete and concentrated attention on these two groups, and because of the care in depicting their eyes, the animals themselves seem to be paying attention, to be watching the artist and the viewer. In cave art, vigilance characterizes both hunter and prey.

The anthropologist Richard K. Nelson describes a culture in which vigilance plays a dominant role in his study of the Koyukon Inuit of northern Canada. These indigenous people live in villages, but they have subsisted historically, and still to a large degree survive, on the animals they hunt. “The intimacy of their relation to nature is far beyond our experience,” he notes, which must have been equally true of Cro-Magnon people. The lives of the Koyukon are characterized by physical dependence on the environment and an “intense emotional interplay with a world that cannot be directly altered to serve the needs of humanity.”22 For the Koyukon the world in which they live is aware and alert. Animals watch the movements of the hunter in the landscape. Disrespect, the violation of prohibitions, any impropriety on the part of the hunter, is immediately known and punished. Because the animals are vigilant, the hunter must be doubly vigilant to succeed in the hunt and to avoid fatal missteps.

It is not hard to imagine that the world of the cave painters was similar to the world of the Inuit hunter. The early humans, like today’s, lived off the land and depended for their survival on the resources that it offered. Without imagining particular prohibitions or ethical norms, it is still possible to imagine the Cro-Magnon painter capturing a world in which survival required heightened awareness. Indeed, the cave paintings themselves are products of exactly this kind of awareness. The ability to draw animals with such grace, fluidity, and expressiveness requires more than manual dexterity and artistic technique. It also calls on resources of memory that have been built over a period of time during which animals of all kinds have been carefully observed. The hunter and the painter, like the animals portrayed, are all watchers.

Certain traits of the cave painters’ worldview are only noticeable through comparison with other representations. In succeeding chapters, it will become clear that most shared visions of what the world is like have focused on things that humans have made. From the Neolithic onward, human societies commonly represented their worlds through lenses of their own creation. The Cro-Magnon almost never represented themselves, and they never represented objects they themselves made. They did not show any of the ways that they may have reshaped the landscape. Indeed, they did not represent land forms at all, just those animals in the landscape that mattered to them. In this way their art called attention to the specifics on which their survival hinged. Their pictured world was a reduction to its bare essentials of the ecosystem that sustained them.