Developments in farming and herding led to the creation of large and complex communities in Old Europe. As this culture was disappearing, both Mesopotamia, under a series of different ruling elites, and Egypt, with its more sedate rhythm of dynastic change, were expanding. In Egypt the Nile and in Mesopotamia the Euphrates nurtured enormous stretches of potential cropland. In Anatolia—home of the third great regional power, the Hittite Empire—there was no single great river or river system, so agriculture depended on rainfall. All three civilizations developed sophisticated and intricate systems to nourish the founder crops. All used oxen for plowing and hauling and donkeys (later horses) to speed communication within their territories. All developed systems of writing that widened the reach of central authority and ensured coordinated action throughout each realm. These mature states were not, as it was once universally believed, the originators of agriculture, but they were great consolidators of the discoveries of multiple cultures scattered throughout the region. As we saw earlier, the nineteenth-century linking of state formation, agricultural expansion, and warfare—a complex that remains intact in many contemporary critiques of Neolithic agriculture—was based on the mistaken belief that these societies were the inventors of agriculture.

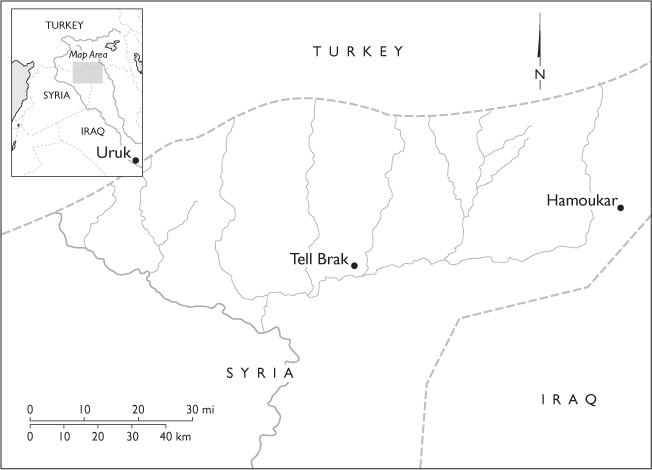

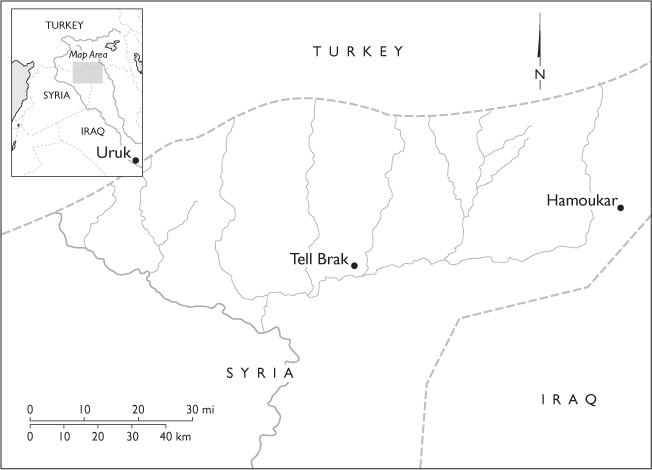

Mesopotamia lies entirely outside the geographical and climatological limits of the Mediterranean region. Culturally, however, the land crossed by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers long experienced the influence of, and exerted power over, the communities of the Levant and the Mediterranean basin. The city of Uruk was the first great power in Mesopotamia. Now some twelve miles distant from the meandering course of the Euphrates River, the city originally stood on its banks. Mentioned repeatedly in the Bible under the name Erech, Uruk is in Sumer, the southernmost part of Mesopotamia; its location was pinpointed in the mid-nineteenth century.

While northern Mesopotamia is a region of high plains that rise in a series of steps from the Tigris River valley to the Zagros Mountains, southern Mesopotamia, the site of Uruk, is low-lying and flat. The shifting intersection of the Tigris and the Euphrates dominates a floodplain and a delta that are crisscrossed by active and abandoned river channels, isolated lagoons, and extensive marshes. This territory was once a rich habitat for deer, wild boar, birds, and fish. The lotus, which has edible roots, and the date palm grew wild. The areas beyond the marshlands were desert. With sound water management, both the marshy soil, too wet for cultivation, and a portion of the arid desert were transformed into high-yield farmland.1

New excavations and explorations have updated the Uruk story. Once it was believed to be unique and foundational—it was the only large city anywhere around—but it is now clear that there were other cities like it upriver. Hamoukar, near Syria’s border with Iraq, has been the scene of excavations during the past decade. Preliminary reports from the still-ongoing explorations indicate that a walled city stood on the site sometime in the first half of the fourth millennium BCE, earlier than the founding date for Uruk in the mid-fourth millennium. Hamoukar had complex architecture that indicated social differentiation, ovens for communal bread-baking, and a symbol system for identifying ownership of goods. Trade in obsidian from a source nearby appears to have been the city’s mainstay. About fifty miles east of Hamoukar, a city buried beneath Tell Brak had monumental buildings that also predated Uruk. Massive walls protected a city there that covered an area of at least one hundred acres. Excavators found ceramic-, stone-, and metal-working areas.

Satellite towns ringed the urban center at Tell Brak. Aerial photographs supplemented by exploration on the ground have revealed more than a hundred towns within a five-mile radius. Between these outliers and the center were large uninhabited spaces that may have been fields or pastures. The regional population might have reached twenty thousand.2 With big cities the traditional regional focus of archaeologists, village cultures have often been forgotten. The common account suggests that with the creation of large cities, one form of the organization of community life gave way to another. But villages continued to grow and thrive while cities developed. Villages aligned themselves with major centers and were no doubt subject to more supervision than they had once experienced, but they did not disappear. Cities, on the other hand, proved to be more volatile. The history of Mesopotamia is marked by repeated conquests of one city by another. In a country without natural protections that could act as a bar against invasion, walled cities were the only viable form of defense. Armies could take refuge behind city walls and shoot down on an attacker from their heights. Destroying the enemy meant capturing and destroying its city strongholds. Villages were mostly undefended and were easier to rebuild if overwhelmed. While cities rose and fell, villages rebuilt and persevered.

Even though modern research has shown that Uruk was neither the only city nor the dominant urban center, it still repays attention. The characteristics that distinguish it and its sister cities from earlier organizations of social life are momentous. Monumentality and a differentiated society that reflected status as well as occupational specialization, an effective leadership hierarchy, large populations densely settled in a complexly organized space, widespread trade, and some kind of symbiosis between center and periphery are their defining traits. The characteristics of Uruk in particular as they have been reconstructed through a century of digging and research are ones that became an integral part of the repertoire of political organization in the ancient world.

The demotion of Uruk and Mesopotamian cultures generally from their position as the founding sites of the agricultural revolution has important intellectual consequences. For historians and theorists rooted in the nineteenth-century political and social world, the primacy of Mesopotamian cultures in the agricultural historical narrative made sense. Their own world was one in which great powers were struggling to manage their resource bases, to govern territories and colonies and assure their monopoly over coercive violence within their territories, and to hone warfare for political use beyond their boundaries. Mesopotamia seemed to them to be a founder society which had—at the very beginning of the agricultural revolution as they imagined it—succeeded in addressing, if not necessarily harmonizing, all three of these concerns.

Urban centers like Uruk, Tell Brak, and Hamoukar flourished in Mesopotamia in harmony with the environment, notwithstanding modern charges of causing environmental degradation.

As we now conceptualize the agricultural revolution, on the basis of the pioneering work of Sherratt and others, Mesopotamia is no longer the point of origin for cultivation and domestication. Grain cultivation, the mainstay of Mesopotamian agriculture, is no longer the key element of the domestication complex, and the proto-nation-state is no longer the necessary moderator of domestication. The history of agriculture, the history of the rise of the political community, and the history of warfare did not cohere inextricably and inevitably as they were once thought to have done.

Irrigated agriculture made possible Uruk and the cities like it that dotted the banks of the Euphrates River. Upriver from Uruk, small rectangular fields bordered a complex of irrigation channels cut into the river’s levees. These fields were flooded in midwinter and the water allowed to soak into the ground. Once their surfaces were dry, the fields were plowed and sown with barley or wheat. The water captured and held by the soil was sufficient to nourish the crop before the summer drought. Downriver from Uruk the field system was different. The fields there were enormous rectangles, up to a hundred acres apiece. At one of its narrow ends, each field abutted an irrigation canal. Fields of similar dimensions were grouped side by side along secondary canals to ensure that every bit of land that could be irrigated was linked to a waterway.

Teams of oxen plowed the long fields in furrows perpendicular to the water source. When the canals were breached and water flowed into the fields, the furrows served as channels for the water to irrigate the entire field. Once the water drained away and left the fields dry enough to work, teams of oxen pulled seed drills through them and deposited seeds in holes at the base of each furrow. This careful deposition of the seed increased productivity, and the fields of Uruk grew enormous quantities of grain.

Compared to plowing and sowing, which could be mechanized, harvesting was labor intensive. Bent low over the furrows, workers grabbed grain stalks by the handful and cut them with sickles. The number of sickles required quickly outpaced the supply of flint or obsidian blades. Ceramic sickles were a substitute, which Uruk potters mass-produced. Clay with a high silicon content produced blades that were sharp when first fired but useless once their edges grew dull. But the blades were so easy to produce that their short life was no problem. Once cut and bundled in sheaves, the harvest was hauled from the fields in ox-pulled carts. Threshing took place on hard-packed earthen floors. Teams of oxen pulled heavy sledges with parallel rows of flint blades on their lower surface to separate grain from straw and chaff.

Surviving records show measurements of field size—both length and width and, with increasing accuracy over the centuries, area. Routinely the scribes recorded information about expenditures for seeding and plowing, crop yields, and ownership of the harvest. Using standardized measures, the scribes estimated outlays of grain for feeding oxen and seeding the fields. During the periods of planting and harvest, overseers issued graded rations of barley to field hands according to a standardized system. Uruk potters created sturdy jugs of a fixed volume to distribute these rations.

To collect, analyze, and store the wealth of data that made the irrigated field system work, the city administration relied on symbols inscribed on clay tablets. As recordkeeping evolved, they produced the well-known cuneiform tablets that scribes throughout the region used. Tens of thousands of such tablets have survived. The earliest documentary tablets now known were uncovered in Uruk. Though their absolute date is hard to fix, they appear to belong to the time between 3200 and 3000 BCE. While later cuneiform tablets were archived, these early examples were preserved entirely by accident. Around 2000 BCE, major buildings in central Uruk were expanded. To prepare the ground for this ambitious project, dirt and rubble collected from many locations around the city were transported to the site. Among the debris were large numbers of discarded and broken clay tablets. As luck would have it, many of these tablets found their way into the fill dirt beneath the new structures, where they were recovered four thousand years later.3

The earliest surviving texts from Mesopotamia do not preserve sacred hymns or laws, philosophical speculations or astronomical data, but the ephemeral “paperwork” of day-to-day agricultural management. This administrative recording system is a distant ancestor of later writing systems. The earliest recordkeeping materials of the Uruk civilization were clay tokens in a variety of shapes that represented commodities. To create an inventory for a shipment of sheep, for example, an appropriate number of sheep tokens were placed in a bag to be handed over at delivery. Since it was all too easy for an unscrupulous trader to remove tokens from a bag and change the official record of a transaction, more foolproof methods soon became common. Typically a number of clay symbols were placed inside a ball of wet clay. Once it hardened, the symbols inside could not be removed without destroying the ball and giving the game away. Next, representations of the contents came to appear on the outside of the clay ball so that shipments could be tallied and verified en route without breaking it. Some products were identified with clay tags attached by strings and marked with a symbol. As shipments were assembled, scribes copied these symbols onto tablets along with notations of quantity. Often the contents listed on the front of a tablet were totaled up on the back of the same tablet.

The shift from inscribing symbols that represented objects to writing symbols that represented words was a crucial step in the development of writing. Many accounting systems like the earliest ones used in Uruk have turned up in various parts of the world. Frequently their discoverers have identified them as the “earliest use of writing” or the “independent invention of a writing system.” But specialists accept that the invention of writing means the invention of a graphic representation of language and not just the picturing or symbolizing of objects. In Uruk the transition from symbols representing things to symbols representing words is easy to document. When the sign for a particular object began to function as the representation of the sound of the object’s name, writing took on the characteristics of a rebus, as today pictures of a pool cue, a bent knee, an eye, and an income tax form might represent “cu-ne-i-form.”

Cuneiform scripts were eventually used to represent all the languages of ancient West Asia. (The Egyptians developed a system with an independently derived set of graphic signs.) The regional predominance of cuneiform is remarkable. It is also a tribute to the usefulness of a ready-made set of phonetic representations. Sumerian, the first written language, is what linguists describe as an “isolate.” It has no affiliation with any other known language. Akkadian, the second language to adopt the Sumerian system of representing syllables graphically, is a Semitic language. It had no etymological links with the freestanding Sumerian language, and what is worse, not much overlap with the phonetics of Sumerian. A lot of sounds and sound combinations native to Akkadian were not present in Sumerian. Still, the Akkadian scribes adopted the Sumerian writing system, evidently convinced that its advantages outweighed its inconveniences. Through the course of the third and second millennia BCE, languages using cuneiform writing continued to grow, though there were many simplifications and adaptations. It was only the adoption of the Phoenician alphabetic system that displaced cuneiform. Even then, the system held on. Cuneiform inscriptions from the first century CE have been found.

By all measures Uruk was huge. By the end of the fourth millennium BCE it covered almost one square mile and may have been home to fifty thousand people. At the center of the city were two temple complexes. The temple of the goddess Inana defined the area called Eanna; the second major temple complex, in the area called Kullab, served the god Enlil. Though on a much-expanded scale, these two structures echoed the smaller temples that anchored village life.

This enormous community was under the control of an interlocked elite of political, religious, and military leaders who took an active, official role in many aspects of daily life. Crafts like potting that were loosely organized at smaller centers were industrialized in the city. Small-town potters built their vessels by hand for the most part, but in the city potters turned clay on wheels. With the potter’s wheel they could work at a much faster rate, and they were also able to standardize production to suit official needs. Other workers may have been organized in guilds or overseen in other ways. The state maintained close control over a portion of the agricultural labor pool.

City leaders encouraged and protected trade in important commodities, both those that sustained the life of the urban population, such as grain, cheese and dairy products, and produce, and those that marked off the privileged elite, such as gold, silver, and precious stones. Trade in metal that served agriculture, crafts, and the military was also closely supervised by the state.4

Egypt may be geographically on the Mediterranean, but through much of its history, the sea played little part in the life of the kingdom. The Mediterranean marked the limit of productive land in the north, just as the desert marked the limit of cultivation to east and west. Only as a continuation of Nile shipping did the sea eventually gain importance for the Egyptians, though it had long served their neighbors. The richest part of Egypt was the Nile Delta. There the river branched out and created a broad triangle of exceptionally rich agricultural land. Currently 50 percent of the population of Egypt lives in the Delta. Memphis, the long-term capital of the ancient kingdom, stood on the southern edge of the Delta.5

Our image of ancient Egypt is a product of more than two hundred years of archaeological investigation and almost five hundred years of scholarly speculation. Archaeologists, artists, and surveyors accompanied Napoléon’s troops as they invaded Egypt in the last decade of the eighteenth century. They collected artifacts and painstakingly made drawings of surviving monuments. This quixotic campaign, which Napoléon himself abandoned when his political fortunes were suddenly on the rise at home, created both Egyptology and the early nineteenth-century fashion for objects in the Egyptian style. From the start, the ruins of Egypt struck both popular and scholarly imagination with almost equal weight. Egypt has kept its large following; other archaeological enthusiasms have come and gone.

The Egyptians’ cult of power, their extraordinary attention to the well-being of the dead, their abundant use of durable stone for building, and the country’s desert climate combined willy-nilly to preserve overwhelming amounts of archaeological material. Egyptian belief in life after death led people of the highest social rank to have their remains preserved. Since they imagined eternity as similar to the life they had enjoyed on earth, they filled their tombs as if they were packing for an extended trip. Not everything would fit in even the most elaborate tombs, and because the lifestyle of distinguished people depended on the labor of innumerable servants and slaves, there was also a staffing problem. Human sacrifice may have been practiced in the earliest periods of the kingdom’s history, but it was not long before a simpler and more economical solution was arrived at. Images replaced actual objects. Scenes painted on the walls of tombs and models filled with little figurines doing all the things necessary to sustain the life of the rich and powerful came to be substituted.

Egypt’s dry climate discouraged the growth of molds and fungus that feed on organic materials. Tomb robbers, on the other hand, stole much of what had been preserved, but since they were more interested in valuables than in archaeological remains, they left a lot of interesting things untouched. Supplementing the artifactual record is an extraordinary wealth of written information. Inscriptions on stone in the hieroglyphic writing of the Egyptians survive in thousands of locations. Decoding the writing was one of the great breakthroughs of nineteenth-century archaeology.

Once decoded, however, these texts offered a surprisingly narrow window on the country’s long history. Whereas cuneiform texts are rich in economic detail, the Egyptian writing system was so complex that it could be mastered by only a relatively small number of people. Hieroglyphic writings are richest in religious texts and royal declarations. Inscriptions tell the official versions of dynastic history, chronicle events in the religious cycle, and memorialize those among the dead who had power and influence.

The life of the nation is only obliquely represented in the art of tombs and in texts and inscriptions. The personalities and concerns even of powerful and distinguished individuals are concealed behind a facade of official actions and attitudes. While it has often been the role of archaeology to bypass the official story that texts present and to chronicle the lives of people who were not considered worth writing about, that has not typically been the case in Egypt. Most Egyptologists have concerned themselves with much the same world that writing presents. Monumental and official culture are well represented in archaeological publications, the cult of the dead is abundantly documented, but the remains of small communities and the patterns of daily life beyond the royal household and the estates of wealthy men and women are not. The relationship between archaeological Egypt and the living nation of the past is distinctly skewed.

The most dramatic proof of that skewing is visible in any voyage along the Nile. Built of stone, the country of the dead—land of monumentality and pharaonic absolutism—still stretches along the Nile at a safe distance from the annual flooding. The agricultural engine that propelled the nation lay in the floodplain itself and in the Nile Delta. Indeed, from the third millennium BCE the Delta was the Egyptian heartland. Here was the breadbasket of the country and its most densely settled part. Thousands of villages built not of stone but of mud brick housed those who fed the kingdom and guaranteed its survival. The Delta and the floodplain, however, are poor environments for archaeological preservation. Muddy soils replenished annually and humid air replace stone and the dry desert climate. The river water that swept over the land destroyed structures while it reinvigorated the soil. What the Nile did not sweep away, the plows of hundreds of generations of farmers broke down or dug up.

The Nile floodplain and delta are ideal for farming and problematic for archaeological preservation. (Photograph from NASA.)

In the remains of the era before the pharaohs became monument builders—the Predynastic Period—and the periods of Greek and Roman occupation, archaeologists have uncovered the agrarian substrate of Egyptian life. Several distinctive Neolithic cultures have come to light. One of the earliest is called Badarian; it may have been in existence as early as 5000 BCE, about the time Old Europe started to flourish, but the confirmed dates are later. The culture appears to have been at its height between 4400 and 4000 BCE.

Known Badarian sites stretch along the Nile well south of the Delta, and traditionally archaeologists had looked to the south for the culture’s origins. The Egyptians themselves believed that their civilization began when African migrants moved upriver. Although the people of Egypt, like all other people on earth, originated in Central Africa, looking for the roots of the Badarian culture in the south proved to be misguided, since Badarian artifacts and forms of subsistence were both firmly linked to the Levantine Neolithic. Domestic architecture and pottery were part of the Neolithic package. So were the wheat, barley, and lentils that the Badarians cultivated. Circular foundations at Badarian sites, once identified as the ruins of houses, proved on further investigation to have floors covered with a thick layer of sheep or goat dung: they were stalls or stables, which adds another imported element to Badarian culture. To reach the Badarians, farming and herding technologies must have traveled from the Levant, along with animals and seeds, by passing through the eastern desert and then going downriver. The Badarians adapted these practices to their environment. What they could grow and when they could grow it depended on the flood cycle of the Nile, which was entirely different from the seasonal cycle of the Levant. There is no evidence of hunting as a way to supplement the diet as there is in West Asia. Fish, however, played a large part in the Badarian diet.6

The great Egyptologist Flinders Petrie first identified the next historical Egyptian culture after the Badarian at a site far south on the Nile where thousands of modest graves were uncovered. The burials were so simple that a generation of archaeologists trained to expect monumentality had found them positively un-Egyptian. It was generally believed that these were the graves of unsophisticated invaders who had somehow established themselves in the kingdom of the pharaohs. A French archaeologist was the first to suggest that the graves might represent something else. He identified them as the remains of a Predynastic culture. This was a novel idea at the turn of the twentieth century, when the earlier Badarian culture was still unknown. It had been a foregone conclusion throughout the nineteenth century that Egypt had come into being through the power and political skill of the pharaohs. The suggestion that any sort of culture might preexist these rulers was met with skepticism.

Cultivating the Nile floodplain, raising domestic animals, and fishing remained the major forms of subsistence at this far southern site. There were new crops to supplement the wheat, barley, and lentils traditionally grown, including Levantine founder crops like peas and vetch. Jujube, a tree that produces a fruit something like a date, and an ancestral form of the watermelon increased the variety of foods available. Pigs and cattle joined the herds of goats and sheep. Wild gazelles brought down by hunters supplemented fish as a source of protein.

The suburb of Maadi near Cairo gave its name to the first culture uncovered in the Delta. While cemeteries had been the representative sites of the Badarian and far southern cultures, excavations at Maadi centered on villages. The material remains of Maadian culture paint a fairly clear picture. The Delta region, also called Lower Egypt, was a crossroads where influences from the Levant and Upper (southern) Egypt blended. The extensive dig turned up houses that mixed Levantine and Egyptian styles. Pottery was cross-cultural. Footed jars from the Levant mixed with flat-bottomed pots made from local clays. The Levantine jars had come filled with oil, wine, or resins. Donkeys, descendants of the wild asses that had long inhabited the region, were the main beasts of burden. The Delta diet was similar to the diet farther south. Wheat and barley were its mainstays. Lentils and peas supplemented the grains and rounded out the protein supply. Pigs, oxen, goats, and sheep were abundant. Dogs were also common and may have been a food source as well as village scavengers and shepherds’ aids.

The last centuries of the fourth millennium BCE were the final Predynastic years in Egyptian history. Increased efficiency in cultivating the Nile floodplain produced enormous amounts of grain. The archaeological evidence, primarily from burials in Upper Egypt, shows that elites were gaining power and wealth. The wealthiest were laid to rest with huge quantities of grave goods around them. As the Upper Egyptian culture matured into its third phase, the regional culture of the Delta disappeared. Archaeologists have long argued that the absence of a Maadi legacy meant that the powers of Upper Egypt had invaded and conquered the Delta. The official records of Egyptian dynasties stretch far into the past, but they do not reach 3000 BCE when the Upper and Lower regions were unified. Archaeology has extended the roster of kings, adding two rulers of special importance, King Scorpion and King Narmer, to the list and pushing back the traditional beginning of the Dynastic Period.

Though sharing crops and linked by trade, Egypt and Mesopotamia had distinct cultural and agricultural traditions. Irrigation in Mesopotamia depended on breaching the banks of the Euphrates and allowing river water to flow into the fields. The annual Nile flooding could be exploited without engineering. The pattern of water management that developed in Egypt was an extension of a natural process. The Nile floodplain had low ridges running parallel to the river that had been created by the river itself as its volume increased or decreased and its course meandered over the millennia. As the waters fell after each annual flood, pools collected behind these natural embankments. Farmers learned to increase the volume of water captured in this way and to use it for irrigation. The process required no central oversight or coordination to make it work. Water capture and irrigation were the job of each village rather than a centralized task, and Egypt remained a country of relatively independent small farming villages into the modern era. The state was highly centralized politically but only loosely organized in other ways. The nineteenth-century belief in the necessity of centralized power to call agriculture into being and supervise its conduct are contradicted by the Egyptian case.

The annual deposit of a thin layer of silt and the natural scouring away of potentially harmful mineral salts made the soils of the Nile Valley and its delta a continually rich agricultural environment. Nineteenth-century Europeans may have been generally contemptuous of agriculture in the Ottoman Empire, but they marveled at the productivity of Egypt. Napoléon reportedly called the country the “breadbasket of the Mediterranean.” It remains highly productive and agriculturally diverse today.7

Political theorists held that the pharaohs called Egypt into being. Pragmatic theoreticians argued that the practical necessity of coordinating labor for huge projects like building the Sphinx or the pyramids was the real propulsion toward social cohesion. More poetic thinkers thought of Egypt as the “gift of the Nile.” The reality of Egypt’s past, however, was not successfully summed up by any of these abstractions. Wealthy, royal Egypt was created by powerful kings who consolidated their hold over the countryside and secured for themselves and others of noble rank or priestly occupation a major share of the abundant preexistent agricultural wealth of the country. This is the Egypt that has long dominated the archaeological record. The annual flooding of the Nile was nothing but an inconvenience to people living near the river until the techniques of farming were imported from the Levant. Then the annual mud bath became a blessing for those with the skills to exploit it. Egypt, like Mesopotamia, was a great power because it was a hugely productive agricultural region. Both great powers were creations not of their rulers or of the waters that fed their fields. They were gifts of the plow.

The reputation of the agricultural powers in the ancient world has suffered at the hands of modern critics. Egypt, which retained its fertility into the present, has been less subject to attack, but Mesopotamia, at present reduced to a barren condition, has been the object of consistent reproach. Since the nineteenth century, Mesopotamian regions like those around Uruk have been charged with environmental neglect and degradation. The motives for both the nineteenth-century critique and the modern one are complicated. In “Ozymandias” the English romantic poet Shelley describes the fallen statue of an ancient despot and the inscription on its base. “My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings; / Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!” Surrounding the statue is nothing but desert where the “lone and level sands stretch far away.” Shelley’s poem had nothing to do with ancient environmental neglect. Ozymandias did not create the desert that surrounded his image. The king’s inscription is a symbol of self-delusion and pride. It was meant as a warning to modern rulers who thought their fame would last forever, not as an indictment of kings long dead.

When nineteenth-century excavators explored the ruins of the civilizations of Mesopotamia, they transformed this poetic cliché. Early archaeologists were not immune to the charge that they were interlopers in the country of a foreign power—the Ottoman Empire—and infidel trespassers in the territories of Islam. As a way of justifying their incursions, they exaggerated the differences between the grandeur of the past and the squalor of the present. This theme, which is common to archaeological and colonial reporting, aimed to break any ancestral link between the communities of the past and those currently occupying the region. It was a tactic, not an offhand observation, and it allowed Europeans to claim that they were the true stewards and rightful heirs of the cultures they were unearthing.8

During the nineteenth century, the devastation of Mesopotamia was attributed to the Arabs, because that accusation suited the ideological needs of the time. In our day, the indictments have been relocated further back in the past. In a recent book, the environmental activists Paul and Anne Ehrlich made the case for resource depletion as the reason for the decline of ancient Mesopotamia, a region which they epitomize in Nineveh, a successor city to Uruk and Babylon. Their critique opens with the contrast between the region in its political and agricultural heyday and its barren surroundings when modern excavators first reached it in the 1840s. (The authors were apparently unaware of the mixed motives of nineteenth-century observers of the Arab world and took their reports as faithful accounts.) While they recognize that warfare and invasion played a role in weakening the region, they point to environmental degradation brought on by official neglect as the source of Nineveh’s decline.

Archaeologists have discovered that the Assyrians and their successors were slowly weakened up through the fifth and sixth centuries AD, by a decline in their natural resource base. One underlying cause of the gradual deterioration of the entire region was deforestation in the hills and mountains, the source of the area’s water supply. Another was environmentally unsustainable irrigation. Indeed, cuneiform tablets from more than 4,000 years ago, before the time of the Assyrian Empire, tell us that irrigation was already causing salts to build up in the soil, and the Mesopotamians lacked the artificial drainage technology that could counter the process. Growers switched from wheat to more salt-tolerant barley, and the area in which any crops could be cultivated was steadily reduced. Those processes weakened the cities and made them more vulnerable to capture. They fell victim to a series of invaders, culminating in the Middle Ages with the Mongols.9

On its face, this is a damning critique of environmental degradation traceable to the “overweening pride, arrogance, and presumption” of ruling elites who were “focused on maintaining their social position, fighting their frequent wars of conquest and defense … but paying little attention to the gradual environmental decay that was undermining the foundations of their civilization.”10

A close reading of the Ehrlichs’ text, however, shows little, if any, connection between the policies and attitude of Nineveh’s rulers and regional resource failure. The Ehrlichs’ implicit reliance on the nineteenth-century link of state formation and agricultural productivity has betrayed them. Taking note of the dates in their description makes it clear that changes in regional productivity had little to do with Nineveh at all. Even by their reckoning, environmental degradation began a thousand years after the fall of the city in 612 BCE. What finally brought an end to the environmental viability of the region, as they see it, was the Mongol invasions of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries CE. Clearly, some degree of agricultural productivity in the region survived the fall of Nineveh by nearly two thousand years.

But even that time frame is too short. Though commonly portrayed as devastating, the Mongol invasions of the Arab world did not put an end to regional agriculture; much irrigated land returned to cultivation after the invaders were expelled. What finally put an end to widespread agriculture in Iraq was not environmental failure at all but the oil wealth that started flowing into the country in the twentieth century. The oil bonanza made farm labor unattractive in Iraq, as it did in many parts of the oil-rich Arab world. Iraq became a net importer of agricultural products because it could afford to do so, not because it had to. The region’s environmental decline in the present day has been accelerated by the damming of the Euphrates River in Syria and Turkey.

Cuneiform records show that salinization only became a problem when population pressures reduced the possibility of letting fields lie fallow. Even in these circumstances, administrators made efforts to counteract salinization by increased sowing of barley, as the Ehrlichs note, and by cultivating shok and agul, inedible plants that served no other purpose than to lower salt concentrations in fields. Far from being an example of neglect, Mesopotamia reflects, in the response to salinization, a constructive adaptation to changed circumstances.

The true history of the regional environment contrasts dramatically with the story told by harsh critics. While individual cities like Nineveh lost their dominant positions, as others had done before them, farm villages continued to produce, and the overall health of the region and its ecology remained on the plus side. Statistics over a long time span—5000 BCE to the present—show a regional population of roughly half a million in the Uruk period, a dip in population in the Assyrian period immediately afterward, then steep growth from the era of Alexander the Great into the Middle Ages. The regional population before the Mongol invasion is estimated at about 1.5 million people.11

In an op-ed piece published in several American newspapers, Jared Diamond describes Mesopotamia’s “ecological suicide,” though he views the disaster as “inadvertent”: “Just as the region’s rise wasn’t due to any special virtue of its people, its fall wasn’t due to any special blindness on their part.” Unlike the Ehrlichs, Diamond recognizes that the “ecological failure” was slow paced: “The original flow of power westward from the Fertile Crescent reversed in 330 BCE, when the Macedonian Army of Alexander the Great advanced eastward to conquer the eastern Mediterranean. In the Middle Ages, Mongol invaders from Central Asia destroyed Iraq’s irrigation systems. After World War I, England and France dismembered the Ottoman Empire and carved out Iraq and other states as pawns of European colonial interests.”12

Diamond’s chronology is more accurate than the Ehrlichs’, but his, too, reflects the nineteenth-century belief that agriculture, state formation, and warfare are indissolubly linked. He takes it for granted that vulnerability to military conquest is a valid measure of the vigor of the resource base of an ancient society.13 This assumption reflects the continued influence of an outdated narrative about the origins of domestication. The yoking of politics, domestication, and warfare characterized theories of the origins of agriculture that have been undermined by modern prehistorians. Ancient warfare and modern warfare differ dramatically in their dependence on a combatant’s resource base. Modern armies supply themselves, but ancient armies lived off the land. An ancient city under siege and the army besieging it shared the same resource base, which was fixed by what either side was able to forage from the areas that it controlled. When critics argue that vulnerability to military attack is a valid measure of ancient resource viability, they are overlooking this fact. They are also overlooking aspects of the historical record.

To demonstrate the weakness of the Mesopotamian agricultural economy, Diamond points to the conquest of the region by Alexander the Great. For him that successful invasion is compelling evidence that the Tigris and Euphrates Valley succumbed to mismanagement. What Diamond fails to point out, however, is that after conquering Mesopotamia in 330 BCE, Alexander went on to conquer Egypt. The “breadbasket of the Mediterranean,” which no one contends was committing ecological suicide, fell victim to the same conqueror who overwhelmed Mesopotamia. In this head-to-head test, then, the strength of the agricultural base did not determine which civilization would be conquered. Egypt’s healthy agrarian system was no defense against Macedonian aggression.

Alexander’s campaigns are not the only test case of the limited power of agricultural viability to predict success or failure in warfare. During the seventh century BCE, successive Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian armies—all based in Mesopotamia—repeatedly invaded Egypt and occupied its capital. Countries characterized as “resource depleted” recurrently conquered a country that was undoubtedly resource rich. There is no reason to accept the conclusions of modern polemicists who argue that ancient Mesopotamia suffered agricultural collapse. The old-fashioned link between the history of state formation, warfare, and domestication is wrong, and it inevitably leads to misinformed conclusions.