The Neolithic culture that took shape over thousands of years involved an assemblage of domesticated crops and animals, a repertoire of techniques, and acquired practices that united the human community with the natural world in a consensus view I call First Nature. Assembling this package was the work of limited population movements combined with multilevel regional trade in seeds, animals, technologies, and concepts. Sharing through trade was the engine that enabled Neolithic communities to capitalize on discoveries and innovations made in distant parts of the region. Time and again, trade overcame the limits of geography and helped to transform the Mediterranean into a cooperative community. Understanding the way this transformation came about and grasping its particular character are essential both to understanding the region in the past and to realizing its contemporary potential.

During the late second millennium BCE, during the so-called Bronze Age, the Mediterranean came into focus as a group of human communities interlocked by trade partnerships. At first, regional trade rested on geographical diversity as the unique products of one region were exchanged for those of another. Over time, trade came to specialize in agricultural commodities or such secondary animal products as wool and cheese. In its first phase, trade spread the wealth of the region’s resources and brought about a regionwide sharing of naturally occurring materials. In its second phase, trade enabled areas with few natural resources to enter a regional economy by trading the secondary products of animal cultivation.

Trade goods traveled in a variety of carriers. Boats were the most technologically advanced and most efficient bulk carriers. Pack and dray animals also came into use, themselves secondary products of domestication. Oxen and oxcarts, donkeys, camels, and finally horses moved goods around the region and beyond. Trade has many detractors both ecological and political, but their arguments are less persuasive in the Mediterranean than in many other parts of the world.

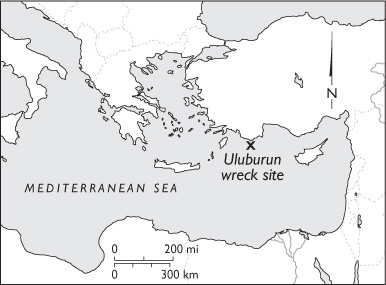

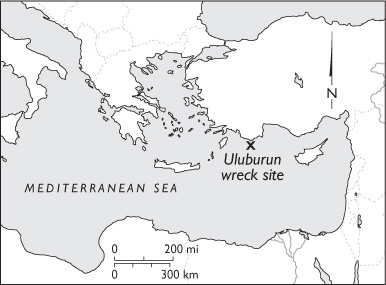

Some of the most powerful testimonies to the extent and nature of ancient trade have come from the archaeological examination of shipwrecks. One such wreck, a trading vessel that foundered off Uluburun on the southern coast of Turkey sometime around 1300 BCE, provided a detailed snapshot of the range and influence of Mediterranean trade in the heart of the Bronze Age. The wreck helped to pinpoint the breadth of trade and the complex relationship among trade, culture, and politics. Discovered by a sponge diver in 1982, the wreck was excavated by underwater archaeologists during a ten-year campaign that began two years later. The wreck site, which was surveyed, chronicled, and excavated with meticulous care, has yielded a wealth of information about the ship’s cargo, personnel, and destination.

The main cargo on board was copper ingots. More than three hundred ingots weighing a total of ten tons were stacked in the ship’s hold. A ton of tin ingots, the proper percentage to turn the whole mass of copper into bronze, was also stowed on board. Ingots of cobalt blue glass were stacked near the copper and tin. These heavy cargoes make the ship seem like a bulk carrier, but bronze and glass, despite their abundance in this cargo, were luxury goods almost certainly on their way to a high-ranking ruler in mainland Greece.1

The excavators found scattered logs of ebony, a precious wood imported from a region as far south as modern-day Somalia, which regional craftworkers used to make high-quality furniture. Traders brought elephant ivory either from the same region or from North Africa; on board there was one large tusk along with fourteen hippopotamus teeth from Egypt, a substitute for ivory. Like the glass, wood, copper, and tin, the ivory had not been worked, which led the excavators to conclude that artisans attached to the court of the purchaser would be ready and able to make it into luxury items of local design.

The Uluburun shipwreck gives evidence of fair trade and diverse exchange around the Mediterranean.

The Uluburun ship also carried large amounts of a naturally occurring arsenic derivative called orpiment, which was used as a pigment in paints and cosmetics. Portions of the shells of the murex, a mollusk, used for making a costly incense, were also on board. Resin from a species of pistachio tree was also being shipped. It was used as a preservative in wine and added as a scent to oils. Olives formed a substantial portion of the cargo, as did pomegranates. Spices shipped included coriander, black cumin, and safflower. There were, in addition, some finished goods and a large supply of beads.

The goods gathered in this one cargo combined products from many parts of West Asia and Africa. Goods that had traveled overland from as far away as the Baltic in the north and the Indian Ocean in the east were included, but most of the cargo came from Egypt, Anatolia, Cyprus, and other parts of the Levant. The copper came from mines in Cyprus, but the odds are that the Uluburun ship picked up this cargo along the Levantine coast. Trade in copper often passed through the city of Ugarit. The sandstone anchors of the ship, plus its lamps and cookware, all came from the same general area, which led the excavators to conclude that some city on the Levantine coast was the ship’s home port.

A team of high-ranking merchants from the Levant were evidently responsible for the ship and its cargo. Accompanying the merchants aboard the ship were two Mycenean ambassadors and their heavily armed guard. The merchants probably represented some West Asian government in its dealings with the ruler of a large and wealthy Greek city. The Uluburun shipwreck suggests that trade in the late second millennium BCE involved partnerships within a cosmopolitan cultural environment. The bulk goods on board suggest that there was no disparity in technology between the trade partners.

Not all trade was like that represented by the Uluburun wreck. During the Paleolithic, trade with few exceptions rested on regional differences in geology. Low-quality flint was exchanged over short distances. High-quality flint and obsidian were traded over much greater distances. Bitumen, like that found near the site of Jericho, gold, lapis lazuli, amber, and other precious commodities were widely exchanged. Even the first steps in cultivation and domestication created new and fundamentally different trade goods. The grain harvested at Jericho at first supplemented and then for a short while may have eclipsed the bitumen trade that had secured the city’s wealth. At Çatalhöyük cattle became a unique trade good that briefly catapulted the city to wealth and regional prominence.

Cultivated grain and domesticated cattle were early proof of the economic power of the Neolithic. The value of domesticates as trade goods, however, was not secure. As the technology of cereal cultivation spread, a low-volume producer like Jericho could no longer compete. Çatalhöyük was bypassed in the same way. Agriculture, rare in the earliest Neolithic, became commonplace as time passed. Both grain and cattle soon lost their status as luxury items and became valuable only in volume.

As long as livestock was simply meat on the hoof, the value of cattle was limited. A localized trade between herders and farmers—an exchange of grain for live animals to be slaughtered within a short period of time—was certainly possible and continued into the modern era. Widespread trade in animal products, however, depended on preservation. Milk and meat spoil quickly and cannot be carried long distances. Cheese, on the other hand, can be transported for days or weeks without spoiling, and it offers many more calories, fat, and salt than the same weight of unprocessed milk. This extra nutritional value makes it possible to sell cheese at a price that offsets the labor costs of producing and transporting it.

The most important of all secondary animal products from an economic standpoint was wool. Sheep and goats could be pastured in areas that had no other agricultural potential. They grazed in summer in mountain meadows where the growing season was too short for grain, olives, or grapes. They fed on slopes that were too steep for cultivation or even for terracing. The supply and demand of wool had an enormous effect on the structure of regional life. Wool is durable and compressible, making it easy to ship over long distances and to store. It can be sold raw or spun into thread or woven into cloth, so labor in one region can be paid for at a distance when the finished product is sold. Wool is also a flexible commodity. Depending on how it is processed, it can suit a variety of economic and market conditions. A shepherd might wear a sheepskin or a heavy woolen pullover knitted from coarse-spun, unwashed yarn. Wool from the same flock might find its way to the workshop of a specialist where it is stripped of oils, dyed, spun, and woven into luxury garments for the very wealthy. Clothes do not last forever. There is a constant need to replace them, so wool does not saturate its market. All these characteristics made it an economic product with revolutionary potential. More than any other good, wool transformed the Neolithic trade structure from one that was dependent on the vagaries of geography to one in which human industry was primary.2

Oil, especially olive oil, is a product with a similar history. Olive oil and preserved olives can be shipped over great distances without deterioration. Oil must, however, be stored and shipped in containers. The containers, made of clay, add to the bulk and especially the weight of the commodity, so the best way to transport olive oil over a distance is in cargo ships. What is true of olive oil is also true of wine. Wine is more perishable than oil, but sealed in clay amphorae, it can with luck be preserved for years. Wine worth exporting is an elite commodity, and its higher price per unit more than repays the cost of shipping.

The advantages of trade have long been recognized by economists, though in recent years there has been considerable criticism of the unequal partnerships that prevail when powerful nations coerce their weaker neighbors into exchanging goods and services at disadvantageous prices. What the Uluburun shipwreck shows is the absence of this kind of one-sided trade relationship in the Bronze Age. If such a relationship cannot be said to have existed between the powerful and sophisticated states of the Levant and less developed Greece, then the regional pattern was probably one in which fair exchange was the norm.

The economist can point to scattered Mediterranean islands and note that most of them were uninhabitable in the Paleolithic because their stocks of wild animals were too small to sustain hunter-gatherer communities. With the introduction of sheep, goats, olive trees, and cultivated plants other than the olive, the islands became habitable. Economies based on imported technologies and domesticates could and did sustain themselves for thousands of years without depleting the soil, water, and natural vegetation on which their survival depended. If this is an acceptable ideal, then there is benefit in trade.

From the ecological perspective, trade is not typically viewed in such a positive light, because trade favors the movement of species from one habitat to another. An ecologist might single out the same islands analyzed by the economist and note the destruction of their megafauna during the Paleolithic and the damage caused to native plants by domesticates and the weeds that traveled with them. The devastation of island habitats worldwide is a familiar and important cautionary tale. Introducing foreign species into fragile ecosystems can indeed have dire consequences. Though the Mediterranean contains many islands, the region as a whole is not a place where ecosystem development occurred in isolation, and islands are not a good conceptual model for understanding its regional biogeography. The Mediterranean is the very opposite of an isolated biological community; it is a massive crossroads at the edges of three continents where species have repeatedly migrated and settled.3

The Mediterranean basin is a robust and flexible bioregion. It has a long history of accommodating invasive species from the multiple different environments that border it. Species are abundant and various there precisely because so many once-exotic species have found a welcome niche. The route by which domesticates spread from the eastern to the rest of the region replicated one of the pathways that invading species had taken for millions of years. Trade in domesticates was the way that the human community unselfconsciously followed these ancient patterns of regional interaction. Diversity is the regional theme, not homogeneity, and trade is one of the forces that harnesses the wealth of diversity.4

The movement of goods in the Bronze Age depended not only on the production of new commodities but on the ability to transport both luxury goods and bulk commodities. The Uluburun ship was not an isolated piece of technology. Rafts and boats made from bundles of reeds carried goods up and down the rivers that irrigated the fields of Mesopotamia and Egypt. Indeed, boats probably made their way along those rivers even before the fields were cultivated. Boats were certainly in use for many thousands of years before any other large volume carrier, like the oxcart, was invented. Until the middle of the nineteenth century boats remained more cost effective than any land-based transport.

River boats were important, but their use was restricted by regional geography. The open frontier that boats eventually conquered was the Mediterranean Sea itself. But the differences between a boat that could navigate the Nile or Euphrates and one that could safely set out on the Mediterranean were substantial—not that humans waited for technological innovations before they set out to sea. There is surprising new evidence that Neanderthals reached Crete on some kind of watercraft. Mesolithic people sailed to the Aegean island of Melos, gathered obsidian, and brought it back to the mainland, where it was traded overland for hundreds of miles. Boats descended from the ones that carried these early traders allowed people in the late Neolithic to migrate permanently to many of the Aegean islands. The main thrust of settlement occurred during the Bronze Age, when seagoing ships came into wide use.5

Ships from many ports sailed the Mediterranean during this era. There is ample evidence of commerce among cities that could only be connected by sea and a wealth of documentary evidence about the goods imported and exported by ship. Descriptions of ships are preserved, along with models of ships and representations that range from room-sized bas-reliefs to graffiti scratched on shards of pottery. There are also surviving bits recovered from shipwrecks and actual preserved boats in Egyptian tombs. Despite this wealth of evidence, however, many details about Bronze Age ships are still controversial, and the archaeology of ancient ships remains one of the most fascinating and challenging disciplines.

Transport on land depended on humans for thousands of years. Then, when domesticated animals entered the picture, a host of new carriers came into use. Aurochs, the first animals to be domesticated, were already doing work for the human community early in the sixth millennium BCE. Almost two millennia later, the ox-pulled cart was developed in Mesopotamia. From there, the oxcart spread both east and west. Ideal for hauling heavy loads over short distances, the oxcart is ill adapted to long-distance travel. A human can easily cover two and a half miles in an hour; an ox a bit less. Oxen require large quantities of food and water, which limits the climates in which they can survive. Carts also have their drawbacks. They work well on flat terrain but less well on slopes. Although they do not require a roadway, in boulder-strewn fields, deserts, and marshes they fail. To be reliable as long-distance transport, ox-drawn carts need the infrastructure of roads and strategically placed reserves of water.

Most long-distance land transport in the Mediterranean region before the Romans built their marvelous network of roads depended on pack animals. The donkey was the first to be domesticated. There may have been multiple domestications, but the wild asses, or onagers, of East Africa and the Levant, of which tiny populations still survive, began to be tamed sometime in the fifth millennium BCE, more than a thousand years after the first attested use of oxen for plowing. Donkeys are compact and short-legged. They are sure-footed, too, so they can be used in terrain where an oxcart would founder or overturn. They eat considerably less than oxen, and since their natural habitat is arid, they require less water. Modern authorities estimate that a pack donkey can carry about one-third of its own weight—seventy to one hundred pounds. Fully loaded, the donkey walks at about the same pace as a human being.6

There are two varieties of domestic camel in the world today, the product of two separate domestications. The single-humped dromedary was first domesticated on the Arabian Peninsula at about the same time as the donkey. Bactrian camels were domesticated in the uplands of western Iran at roughly the same time. Through subsequent history the two species have remained the most practical and functional animals in the difficult terrains to which they are native. The Bactrian camel is at home in the cold northerly steppes and deserts that stretch from Iran eastward to China. The dromedary is still widely used in the hot desert countries of West Asia and North Africa. The ability of both species to forage on scrub and to go long distances without drinking is legendary. A single dromedary can carry the load of six or eight donkeys. A Bactrian camel can carry a one-ton load on its back. Both can cover thirty miles a day in terrain that is too arid and unstable to support a donkey.

In regions where the horse could survive, it became the dominant, multipurpose animal. Domestication began sometime around 4000 BCE in the steppes north of the Black Sea. From there the horse spread rapidly both east and west. As ships increasingly linked communities around the Mediterranean Sea, the horse transformed land transportation. The horse was the ideal animal to bring the kind of swift and decisive change that Gimbutas imagined overtaking the ancient world of matriarchy. Where Gimbutas and earlier archaeologists saw mounted invaders, however, contemporary archaeologists, supported by genetic evidence, see a wave of advance. This view is attuned to the slow pace of cultural change. What it lacks is the dynamism of invasion theories, a dynamism connected historically with the horse.

The cave painters of France often represented wild horses, and the remains of horse bones in cave deposits show how important a part of the Paleolithic diet horse meat was. At the end of the last ice age, climate change promoted the growth of forests, and the open plains where horses had thrived became overgrown. This dramatically reduced the range of the wild horse, which ceased to be an important source of meat in areas where it had once been primary. About 4000 BCE horses show up again in the archaeological record. Wild horses had survived and thrived north of the Fertile Crescent in the open grassy steppes of the Caucasus. Nomadic peoples there captured and used them in a variety of ways.7

Once the horse had been tamed in the steppes, it soon showed up elsewhere in Asia and Europe, as the archaeological record shows; it expanded rapidly into areas where it had not been seen for thousands of years. Unlike most domesticated species, however, which show a single point of origin and a gradual spread from the Fertile Crescent both east and west, horses spread in a more complicated pattern.8 Evidence for the unusual pattern of repeated domestication of horses comes from genetic studies of modern horses, which show greater diversity than any other domesticated animal. This genetic diversity has led to the conclusion that the widespread use of horses “occurred primarily through the transfer of technology for capturing, taming, and rearing wild caught animals.”9

Sometime in the early third millennium BCE, the horse reached Mesopotamia. At first horses were treated like faster oxen and yoked to carts and plows. Not all carts carried grain. Rulers and warriors had their own vehicles, a few images of which have survived. Typically their carts were four-wheeled conveyances with a raised front, side rails, and room for two to stand inside. In a surviving copper model from about 2500 BCE, two oxen pull the cart. In a battle scene from a wooden box called the Standard of Ur, a chariot is pulled by a team of four donkeys. Two of the donkeys are harnessed to the yoke pulling the cart, and two others are bridled but otherwise free. The outer two free donkeys set a pace which the inner pair, despite the weight they were pulling, would attempt to match.

Heavy chariots with four solid wooden wheels were neither fast nor maneuverable. It would not be hard for foot soldiers to get out of the way of ox-pulled chariots. Both speed and turning were improved when chariots were mounted on runners rather than wheels. Sleds could turn corners more easily than four-wheeled carts, but friction was an obvious problem in many terrains. Two-wheeled carts were lighter and faster and more stable on turns, but the solid wooden wheels kept speeds down.10 Oxcarts might travel at two miles an hour; horses pulled light chariots at speeds of up to twenty miles per hour.11 Sometime in the second millennium BCE, lighter and stronger wheels with an outer rim supported on spokes were invented; they quickly became standard equipment on chariots throughout West Asia. Between 1600 and 1200 BCE the region was embroiled in recurrent wars, and the chariot became a major resource for every regional fighting force. Numbers, though hard to pin down, suggest horses were used for war on a staggering scale. Solomon, who ruled over a minor regional power, claimed to have twelve thousand horses ready for battle.12 The rulers of the great powers must have commanded many more.

By about 1000 BCE, a new way of using horses began to develop, perhaps first among the steppe peoples who had the longest experience with them. Instead of harnessing horses to carts, people mounted horses and rode on their backs. Bridles developed for handling cart horses could readily be adapted to this style of riding. Saddles, which developed next, improved riders’ ability to hold their seat. As skills and agility increased, mounted riders armed themselves with short bows. The Scythians of the Caucasus and the Parthians of West Asia were adept at this style of fighting. Because of their special fighting abilities, they were able to resist attacks by the great powers of eastern Asia and their successors, the Greeks and the Romans. Most experts believe that the stirrup was the only major tool of horse management that was unknown in the ancient world. Its invention is usually dated to the early Middle Ages.

Trade not only spread commodities and techniques across the Mediterranean; it also brought different cultures into prolonged contact, and contact often led to settlement. People of one culture began to live within the boundaries of another culture group. Multiethnicity, which we might also call diversity, was not valued in the nineteenth century, and its presence in the historical record was typically downplayed or overlooked. Indeed, there was considerable prejudice in the nineteenth century against the mixing of peoples; intercultural and especially interracial marriage, for example, were strongly condemned. It is probably safe to say, however, that ethnic unity played a relatively minor part in the majority of world political systems before the nineteenth century. The history of conquest in the Mediterranean region from the Bronze Age onward underscores this thought. Regional communities with governments that change with the tides of conquest are not likely to be ethnically uniform.

The benefits of ethnic uniformity are obvious, and the romantic folk-based ideologies of the nineteenth century enumerated and extolled them. In these systems everyone shares a common culture and a common language; everyone’s beliefs and values are substantially the same. It is wise to remember, however, that the rise and spread of these ideologies coincided with the rise of the modern nation-state and that thinking of this kind helped to suppress divisions within societies that had been long-standing. Although diversity has many advocates today, its advantages are less obvious. Diverse systems inevitably pit contrasting beliefs against each other; they invite clashes of culture and misunderstandings that reflect lack of a common experience, a common religion, or a common language.

Despite the potential for conflict that diversity inevitably produces, its benefits can be substantial. Culturally diverse systems tend to be more dynamic than homogeneous ones because a wider range of cultural predispositions means a wider range of potential responses to threats and opportunities. Ethnic and cultural diversity in the social order function in a way that is analogous to the division of labor in the economic order, and in many instances, the two systems interlock. Throughout history, occupational specialization and ethnic difference have often coincided. In many societies herders have been ethnically and culturally different from the populations that lived in towns and grew crops. In other societies it has typically been the case that particular skills or occupations are associated with particular ethnic groups. Some Egyptian temples were frescoed by Minoan artists from Crete. Pharaohs hired Greek soldiers to protect them. The Nile Delta, which connected Egypt to the rest of the Mediterranean, was also home to many foreign colonies. We have imagined diversity to be a contemporary ideal, but it has a long and important, if underappreciated, history. It was a significant feature of the Mediterranean throughout its history.