My family, friends, and acquaintances don’t think I need to lose weight

This chapter was requested by several people for various reasons. The above statement is, of course, pretty loose, because it’s not necessarily related to fat logic — or at least, not that of overweight people themselves. In this case, it’s the people around them who succumb to fat logic.

And of course, this statement is only fat-logical when referring to people who are not underweight or for whom losing weight would mean they would become underweight. If an anorexic person expresses the desire to become even more underweight, it’s obviously not fat logic when friends and acquaintances react negatively. So this chapter is only about the reactions to someone wanting to reduce their weight to a healthy BMI (above 18.5).

I could probably write an entire book on this subject. Let me start with my own experience. When I weighed 150 kg, there was no one who seriously claimed that losing weight would not be a good idea for me. Apart from my mother, though, as far as I can remember nobody ever asked me about my weight, in all those years. My weight was the elephant in the room, which no one mentioned — until I brought it up myself.

At some point I got into the habit of casually mentioning my weight to signal that I had no problem talking about it. People usually reacted with relief, as if they had just been allowed to see my obesity, after they’d apparently been trying not to notice its existence. In my experience, that’s quite a common reaction to overweight people (‘Don’t acknowledge it, whatever you do!’), but above a certain weight — and 150 kg is definitely above — it becomes farcical.

Doctors never mentioned my weight unprompted, either, which was a relief for me at the time, but which I now view more critically. I don’t know if it would have helped to talk about it before I was ready. But it did make it easier for me to convince myself that my weight was not a problem. For a long time, my husband didn’t notice that I’d gained weight. Not until I told him myself that I’d put on 20 kg.

Because he saw me every day, it’s not implausible that he didn’t notice, because my weight gain was very gradual. But he still found me attractive, and I think he also wanted to believe my self-deception about the health impacts of being overweight whenever I told him about the latest articles that showed that obesity wasn’t so bad for you. Especially because he had also gained weight over the course of our relationship and was on the verge of class II obesity — and friends or colleagues would often mention his big belly and tease him about it.

When I started losing weight, I didn’t tell anyone about it. My family lives 600 km away, and I didn’t see them until ten months later. I originally intended to keep them completely in the dark, but after six months, I decided that was going too far. So I took my knee operation in April 2014 as an opportunity to tell my family about my intention to lose weight. When we met in September, they thought I’d been losing weight for about four months. My mother had also started losing weight at the beginning of 2014, and thought she was my inspiration. In fact, I think it was the other way around, as I’d already mentioned a few of my new insights when we spoke on the phone (‘Do you know that there’s no such thing as starvation-mode metabolism? I always thought I’d ruined my metabolism by dieting, but it looks like I was wrong …’ or ‘Wow, I just read that there’s no such thing as a fast or slow metabolism, or at least the differences are apparently very small … I’ve probably just been eating too much.’) At the time, I found it good to talk to my mother about being overweight and losing weight, even though she didn’t know much about the process I was going through. She was having very similar experiences, for example, with friends and acquaintances who were ‘worried’ that she might get ‘too thin’.

I was also supported by my husband, who had noticed all my problems with my body and had started to question all his repressed concerns and excuses, just like me.

People often ask me what my husband thinks of my new weight. After all, I weighed about 85 kg when he met me, 150 kg when he married me, and now I weigh 65 kg. That’s a lot of ups and downs, and a lot of people can’t imagine a partner going along with it.

But a look at his former girlfriends reveals some who were very fat, some very thin, some medium … there have been all sorts. It seems he really doesn’t care about body size, but he doesn’t want me to get overweight again, especially considering how it affected our lives and my health. It wasn’t until months after I’d lost weight that he confessed to me that he, too, had been afraid that I might eventually become dependent on constant medical care.

He was basically the only person who was unreservedly encouraging and supportive. He also lost 15 kg, and he came to the gym with me. I think he really was more than normally wonderful in this respect. While surfing through weight-loss forums, I often read about partners who secretly sabotage their loved one’s diets or openly say they don’t want them to lose weight. The terrible thing is that that kind of behaviour isn’t socially condemned the way it should be.

If someone said that they would find it unattractive if their anorexic partner were to achieve normal weight, they would be guaranteed to be told that theirs was a lousy attitude, and that their partner’s health was the most important thing. But when someone says that they prefer ‘big’ and wouldn’t want a partner who was ‘all skin and bones’, it’s usually accepted or even seen as positive. And as soon as someone takes a critical view of the fact that their partner has put on weight, they can expect to be called an arsehole.

Sure, with my weight at 150 kg almost everyone would have understood if my husband had left me. They would have nodded sadly and said my weight really was extreme, so it was understandable. But what if I’d just got a little chubby? Maybe even after having children? He would be expected to accept that — or else expect to be seen as a superficial arsehole.

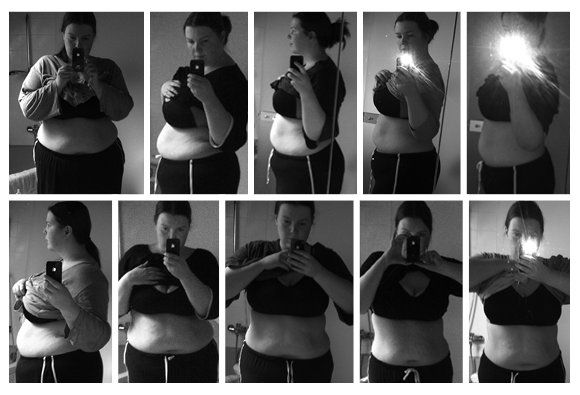

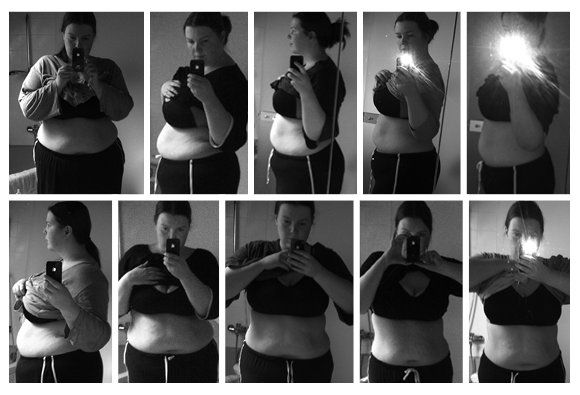

As far as the broader world beyond my marriage is concerned, I lost my first 40 kg in secret, so to speak, without anyone noticing. When I reached about 105 kg, everyone around me suddenly noticed that I’d lost weight. At over 100 kg, I was still very much within the obese range, but others saw it quite differently. From all sides, I was asked, surely I didn’t want to lose any more weight, did I? I must be done with my diet now, right? Yeah, that’s terrific losing so much weight, but you don’t need to lose any more — surely?

A neighbour who saw me gardening worriedly asked my husband how much I now weighed and asked him to please make sure I ate more. When I ran into a colleague on the street, she half-jokingly asked when I was going to be diagnosed with anorexia, and another colleague admitted that he deliberately hadn’t reacted too enthusiastically to my new size, for fear I might go to ‘the other extreme’.

The subject of anorexia was brought up more and more by friends and acquaintances. Not that it was directly applied to me, but there were warnings and expressions of concern. There were stories about friends who had also lost a lot of weight and then become anorexic. It was ironic: when I was sick and almost bedridden at 150 kg, no one had ever expressed concern or commented on my weight in any way. And then, when I had lost 40 kg, I was able to walk again, and I was feeling better than I had for years, people started to get worried about my health? It was as if my body had suddenly become a public forum where everyone was allowed to give an opinion after years of it having been a taboo subject.

Interestingly, it seems this was also only a phase, because now that I’m actually ‘thin’ at 65 kg, those comments have dropped off a lot. The same people who thought, when I was 100 kg, that I would be too thin and an ugly bag of bones if I lost just one more pound, now either say nothing or tell me I look great.

Psychology can naturally offer an explanation for this, because we always perceive change as being more drastic than stability. When a plane takes off, the speed seems to be faster than it does during flight because we’re pressed into the back of the seat by the acceleration. It’s probably similar with weight loss, where the weight loss is perceived as more extreme than the stable lower weight after people have had several months to become more familiar with it. Criticism from people around you in this respect is probably something that you just have to endure stoically until people get used to your new appearance.

But that isn’t easy to do. Often, people don’t limit themselves to harmless criticism or concern, but really become aggressive and censorious. When I started blogging about weight and how society has normalised obesity (I come back to this in the next chapter), I received several emails from people telling me about the response they got to their losing weight. Here are a few examples:

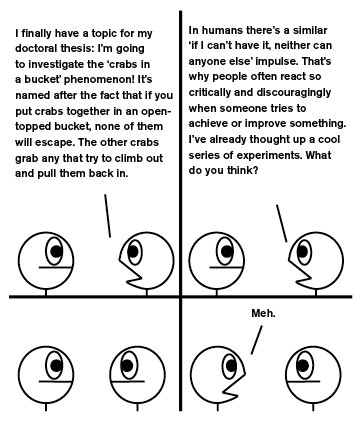

To be honest, what I found most difficult were the people around me who were constantly trying to convince me that I was anorexic or that I was killing myself ‘by degrees’ (and that coming from smokers! …), and also the people who kept sending me food parcels out of ‘concern’. Some people actually begged me to put food in my mouth and were more than a little offended if I didn’t eat as much as they wanted (parents and grandparents especially). And of course, the constant know-it-all comments like ‘Your body’s long since gone into starvation mode — you have to eat more!’ or ‘Just one meal a day? You can’t tell me that your body isn’t missing nutrients.’ I took comfort in the fact that these people obviously had a different perspective than I did. For me, I can’t be called ‘skinny’ if I can grab enough fat on my hips to really make a handful. I know how much I still want to lose, and I now know that it is perfectly possible. And I also think that a lot of the objections from others come from an ‘if-I-can’t-have-it-neither-can-you’ mentality: ‘I wouldn’t be able to do it, so you can’t do it either. And if you really are getting thinner, then it must be unhealthy in some way. Otherwise, I’d have to come up with a new excuse for not doing it myself.’

I started being more careful about what I ate, and stopped, for example, eating cake just out of a sense of conviviality with friends. I also refused sweets offered by [my friend] when I wasn’t in the mood for them. Then my friend accused me of starving myself and refused to believe that I liked eating the cucumber and kohlrabi sticks I brought to work as a snack. It escalated when she visited me unannounced and ‘caught’ me leafing through a weight-loss and fitness magazine. ‘You’re sick! I want my old friend back! Can’t you tell that you have an eating disorder? And your obsession with exercise is way over the top!’ I was lectured, and then she drove off. After that we didn’t talk for a while, but now we’re back on speaking terms. But the topics of nutrition, exercise, and body weight are still red rags to her. I find myself hiding fitness magazines from her and hastily making sure no such incriminating publications are around when she visits me. I don’t tell her about all the sporting activities I do when we’re not together. Although she herself talks about practically nothing other than how many calories there are in certain foods, and tells me regretfully each day what she’s eaten, I now completely avoid the subject, because I don’t want to be told off for ‘being incapable of talking about anything else’. Sometimes, I even lie to her when she delivers her ‘diet report’ and then looks at me expectantly, and I know that her guilty conscience will not be soothed if I don’t admit to eating at least as many calories as her (at the time she accused me of having an eating disorder, one of the things she accused me of was always being careful not to eat a gram more than she did when we were on holiday together. I was very upset by that accusation because I hadn’t paid any attention at all to how much she ate. But she was quite adamant, because she had watched closely and counted how many plates I had eaten when we went for sushi …).

I, 1.80 m tall and a proud non-smoker for 11 months, recently got on the scales and weighed 76 kg for the first time. As long as I can remember, my weight has always fluctuated between 69 and 72 kg. Well, there was nothing for it: losing weight was the order of the day. No more sweets, and a few push-ups and crunches until the extra weight is gone (I know, only partly useful for losing weight, but when you lift down the sixpacks from the top shelf, a sixpack is what you want to see).

My wife’s reaction was more negative than positive. She liked the fact that I’d put on weight, and now she sees herself almost forced to follow my example (she has gained 17 kg in the last 22 years). Others I’ve told have been more combative: ‘Where have you got spare weight to lose? What am I supposed to say??’

So, it’s better to keep quiet about it. I now weigh between 72 and 74 kilos … I’m getting there.

So, after starting to get this feeling of success from comments like ‘Oh wow, you’ve lost 10 kilos! And where did your thighs go?’ I’ve also, kind of unconsciously, started to dress differently. Just dressing more confidently, in clothes I felt made me look nice instead of just less horrible. Before, I used to wear several layers and often long concealing tops (a bit strange, since I was only a little overweight, but we all have our issues^^) but now I’ve started wearing tighter clothes again. Suddenly, the people around me realised that something had changed. The same people who used to say, ‘Oh, nonsense, you’re nowhere near fat! You can eat that, no problem!’ are now the ones saying, ‘Ooh! You’ve lost a lot of weight! Are you all right? We don’t want you wasting away to nothing!’ At every. Damned. Opportunity … I’ve even caught myself putting on extra baggy clothes to avoid these stupid comments when I’m meeting some of the worst offenders. I’ve also noticed that those people have started giving me bigger pieces of cake at birthdays and putting more food on my plate at dinner parties. (This isn’t just in my head — I’ve kept lists!^^) This is deliberate sabotage!

I could probably show you hundreds of reports like this — and they all follow more or less the same pattern:

In my case, I was often asked about my target weight, which is in the average normal weight range: 63 kg, with a height of 175 cm, which means I have a BMI of about 21. And although that is a reasonable target, especially considering my damaged joints, everyone, without exception, told me it was ‘too low’.

What is shocking is that even my family doctor was uneasy about my target. When I spoke to her while I was still very overweight, she played down the issue and advised me first to try to get somewhere approaching normal weight — that would be great (it sounded more like ‘That would be a miracle’). As I got closer and closer to normal weight, she became increasingly critical of my target of 63 kg but was unable to say what exactly bothered her about it, and she had to admit that it was a good target in terms of the risk of osteoarthritis. When I weighed 70 kg, she said that it was enough, now, and that I was looking pretty thin. She asked what my BMI would be at 63 kg — surely in the underweight range? When I replied that it would be 21, she pulled out a little slider calculating chart and eventually muttered that it was true. But she insisted that she still thought it was very low.

If you’ve read the section in this book on health risks, you will surely have realised that a BMI of less than 21 is associated with the lowest health risk for women. So, in purely medical terms, my doctor should have welcomed my target weight. And she couldn’t provide any medical argument against it. Nevertheless, she was visibly, audibly, and tangibly uncomfortable with my aim to become ‘so thin’. Her reaction was typical of almost everyone around me.

What I found particularly annoying was that, without even asking, people often assumed, and still do, that I had lost weight purely for reasons of appearance, in order to adhere to ‘society’s ideal of beauty’. Often, it doesn’t help to point out that I actually lost weight for health reasons.

Why do people so often react in such a negative, critical, or hostile way? The people in the comments above mentioned some theories, from the ‘if-I-can’t-have-it-neither-can-you’ mentality (often called the ‘crabs in a bucket’ mentality) to envy or a guilty conscience. I think, purely intuitively, we all know what the reason is.

But the real question, in my opinion, isn’t ‘Why do they do it?’ but ‘Why do they think they can do it?’

Why is it so socially acceptable to criticise someone for losing weight?

I think this has something to do with the skewed perception of body weight in our society in recent years.