[Anti-fat logic] Now, I’d still like to know a few tricks!

Most of this is interspersed throughout the previous chapters, but since several people have asked for it, and it’s almost obligatory for a psychotherapist writing about weight loss, here are a few psychological aids — or at least possible aids, since they’re based on statistics, and every individual must ultimately find out what works best for him or her.

First of all, a basic point: I deliberately avoided going into too much detail in this book about my own weight-loss experience. I have mentioned several times that I restricted my daily caloric intake to 500 kcal at the beginning of the process. This was because of the particular situation I was in. Since I couldn’t do any exercise and was under relatively large time pressure, I decided to go for extreme calorie reduction. At the time, I found it astonishingly easy, but it still meant that I ate very little, and my diet was very ‘boring’. I mainly ate poultry with a few vegetables, or low-fat curd cheese with protein powder, and of course vitamin and mineral supplements. Anyone can do that, but in most cases and for most people it is unnecessarily extreme. For most people, a 1000 or 1200 kcal diet represents a relatively large deficit and results in the loss of about 1 kg per week. At the same time, 1000 kcal allow for a significantly more varied diet than 500 kcal.

In order to make sure I had enough protein in my diet, I was forced to eat almost exclusively low-fat and low-carb foods. Even fruit was banned from my diet at that time for nutritional reasons. If you’re at a point where stealing a slice of mango from your husband’s fruit salad is a sinful treat, you know you are eating a very restricted diet. When I started gradually increasing my calorie intake, I found eating even 1000 to 1200 kcal very enjoyable.

But there was another reason I didn’t go into more detail about my personal diet plan: I think it’s important for each individual to find what’s best for them, and I don’t think much of expounding a certain method and claiming it is suitable for people with very different personalities.

In general, there are several different kinds of diet:

- Counting. Counting diets include all those which don’t prescribe a particular way of eating, but impose a restriction on calorie intake. You can follow this path individually, or you can follow a program like the one run by Weight Watchers. Programs like those simplify calorie counting by translating it into a points system, making it less complicated (but also less precise). The advantage of these kinds of diets is that you can still eat all types of food, so they’re very flexible. The disadvantage for some is that they find it tedious to count.

- Food restriction. This includes those diets which indirectly restrict the amount you eat, by changing the kinds of food you consume. There is no conscious calorie counting, but the choice of allowable foods increases the likelihood that you will automatically feel less hungry and therefore eat less. These diets mostly restrict the intake of (simple) carbohydrates and/or processed foods, and encourage the eating of either high-protein or high-fibre foods. Low-carb diets like the Dukan, Atkins, or paleo diets fall into this category, as do raw-food diets, whole-food diets, and some vegan diets (although, many sweets and confectioneries are vegan, as is sugar itself, so veganism doesn’t necessarily entail a low-calorie diet). When certain foods are forbidden, many people automatically eat less overall. For one thing, the ‘permitted’ foods are usually more filling, and for another, the effect comes simply from the more restricted choice. The more choice we have, the more we eat, and conversely, a restricted palette of available food types makes us eat less. The advantage of this type of diet is that it allows you to lose weight without feeling restricted in the amount you can eat. The disadvantage for some people is that by ‘banning’ certain foods, they do feel very restricted in their choices. In addition, for some people, these diets don’t ‘automatically reduce their appetite’. I, for example, can eat huge amounts of raw vegetables and could gain weight even when eating only fruit and veg. Given that I love cheese, a low-carb diet would be no obstacle to ‘achieving’ a calorie surplus for me, I’d just guzzle massive amounts of cheese.

- Eating rules. This includes diets that limit calorie intake by imposing certain rules. Intermittent fasting is an example of this, in which eating is only allowed during a short time window each day (e.g., between 8.00 am and noon) or regular fasting days are kept (e.g., only water and vegetable broth on Tuesdays and Fridays). In theory, barmy diets like ‘food combining’ should be included in this category. These diets work by establishing certain rules and structures that amount to food restriction of some kind. The advantage is that a lot of people find it easier to stick to a clear set of rules. The disadvantage is once again that some people can’t be ‘tricked’ in this way. For example, again, for me it would be no problem to eat more than 2000 kcal in the space of four hours, so a time restriction would not automatically make me thinner.

- Dieting aids. This includes anything that makes it physically more difficult to eat (a lot). In theory, this should also include stomach reduction surgery. ‘Stomach fillers’ like konjac flour or chia seeds, for example, swell up in the stomach and create the feeling of being full. The advantage here is that some people find they no longer feel restricted in the amount they can eat. The disadvantage is that less extreme measures such as this often don’t work and some people will continue to ingest too many calories on top of the filler.

- Dietary plans. These are, of course, also based on calorie reduction, but they aren’t flexible and they are not created by the dieter but are pre-defined. They may take the form of set shopping lists and recipe collections, deliveries of pre-prepared meals, or a plan drawn up by a dietitian. The advantage is that such plans are usually very well thought-through and include creative and varied meals. They also reduce the amount of planning you have to do yourself, and many people also find it easier to stick to a pre-determined schedule. The disadvantage is that they are imposed from outside and are often very costly — either financially or according to the amount of time they take. Or both.

- Meal replacement. This type of diet includes all those in which regular meals are replaced in some way. Either in the form of shakes (for example, Slimfast) or by such foodstuffs like juice (juice fasting), cabbage soup, or similar. The advantage is that these diets are relatively simple. The disadvantage is that they usually mean eating becomes boring, rather unpleasant, and monotonous. They can often lead to nutritional deficiencies due to their repetitious nature, and in my experience at least, drinking the same shakes day after day soon makes you so sick of them that the mere thought of drinking another one immediately makes you retch.

- Increasing the body’s calorie consumption. This weight-loss method attempts to create a caloric deficit by increasing activity, without changing eating habits to any significant degree. One hour of intensive(!) exercise each day can easily lead to weight loss of half a kilo a week, while you continue to eat ‘normally’. (However, those who have gained weight continuously should understand that such an exercise program may simply halt their weight gain if they don’t also change their eating habits.)

It’s impossible to generalise about which type of diet is best. Of course, some forms of dieting fundamentally make more sense than others, or are more likely to lead to success, but there will also be particular types of people who find the best success with their own way of dieting. Personally, I don’t have much time at all for juice fasting, as I find drinking calories completely unsatisfying. However, a few weeks ago I read about a woman who lost huge amounts of weight with that method after many other diets had failed. I also don’t see the point of spending money on programs like Weight Watchers, when I can do the same thing for free (and more accurately) myself, simply by counting calories. On the other hand, I do understand people who prefer to spend money on gaining access to a simplified points system and also have the opportunity to join a support group.

I think one way of finding out which method suits you best is to analyse the nature of your problem. I would advise everybody to keep a food diary for a week. Ideally, it should be very precise, i.e., with all food weighed out. The information on calorie intake can then form the basis for exploring where the problems might lie. Sometimes this can actually lead to a very simple solution. Someone whose problem turns out to be one of high-calorie snacking between meals might solve it by restricting their meals (e.g., with intermittent fasting) or by changing their eating habits (replacing sugary snacks with raw vegetables). If the problem turns out to be portion size, this could be helped by changing the composition of meal elements (more protein or fibre in the form of vegetables), since this leads to a more rapid feeling of satiety.

Those who have already tried many different methods can use that accumulated experience as a basis for analysing which method worked better and which less well, and then base their diet program on that. Those who have no idea what suits them should try a few different methods out, for example by counting calories for a couple of days, eating a low-carb diet for a few days, trying meal-replacement shakes, or testing a commercial diet plan. Those of a more adventurous bent might want to seek out a number of different programs and then select one at random each morning (by drawing a card or rolling dice).

I think it’s absolutely essential to gain at least a basic reading knowledge of nutrition — for example, by looking up the nutritional value of various types of food, calculating your own body’s energy and protein requirements, and analysing your own eating behaviour. Not only from the point of view of calorie content, but also from the point of view of a balanced supply of necessary nutrients. Nutrition is one of the most important things in our lives, since it has a direct influence on quality of life. Deficiencies directly affect our ability to function and our long-term physical and mental health. A few hours of work to learn about nutrition (and exercise) might be one of the best investments you can make in your own quality of life.

Everyone who wants to lose weight should find their own path. There is no such thing as the ultimate trick, the one rule, or the one single way of eating that you have to follow. The important thing is to find the best way for you to implement the basic, simple idea (fewer calories in than out).

Below is a list of a few minor, basic pointers that might be of help:

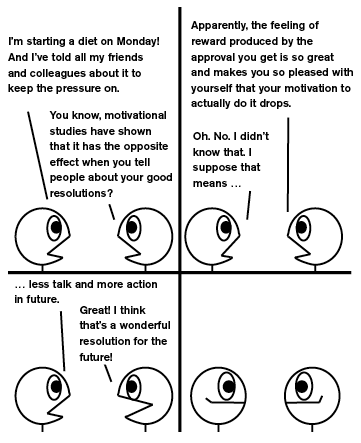

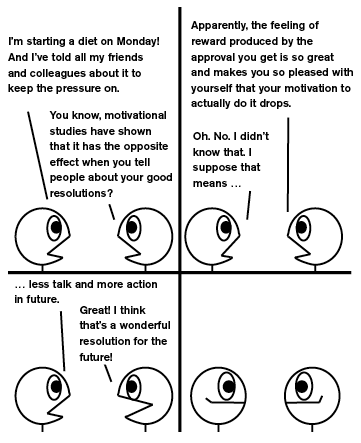

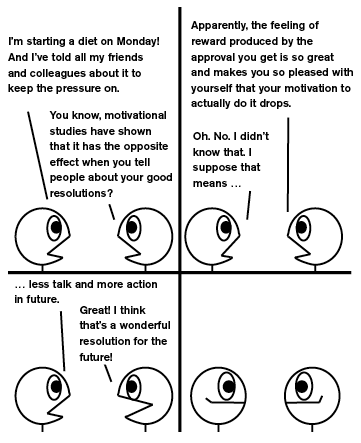

- ‘The more people I tell about my diet, the more likely I am to stick to it’ is a myth.

- Positive fantasy and reality. Apparently, the most motivating combination is one of positive fantasy and hard reality (Oettingen, 1996). Hard reality in the form of regular weighing or measuring, depending on personal preference, is not difficult to implement. My motivational fantasy was my first visit to see my family — after almost a year of losing weight without them knowing. I imagined how shocked and happy my mother would be. Incidentally, the reality was in fact almost as I had imagined it. The last time my mother had seen me, I’d weighed 150 kg, and when she saw me again, my weight was almost exactly half that. She stared at me, completely speechless, for about two minutes and then was totally overjoyed. That fantasy gave me a lot of motivation, and at the same time, I weighed myself every day and followed the curve on the graph to work out what my weight might be by the time I was due to see my mother.

- Concrete resolutions. For me (and not only me), a successful strategy for ‘keeping it up’ was to make clearly formed resolutions. Instead of saying to myself I will do more exercise or I’ll go jogging more often, I made resolves like I will do a quarter of an hour’s upper body training every day before I watch the evening news or Every Tuesday and Thursday after the team meeting at work I will go straight to the gym. Attaching the resolution to a concrete external trigger takes the decision away from your brain, so to speak, making it more likely to happen automatically, and less likely that you will start vacillating about whether you should do it or not, so you’ll just do it.

- Stimulus control. This sounds simple but it’s extremely effective: simply do not keep temptations within reach, and instead, place things you want to do within your view. Not keeping sweets at home, making it necessary to go out and buy them especially, creates a considerably higher hurdle to overcome. And keeping your cross trainer constantly at the ready in front of the television, rather than covered in clothes in the corner of your bedroom, will make overcoming unwillingness to exercise that bit easier. I found home-made popcorn works very well as a substitute for ‘sweets’ (if, like me, you eat it fat and sugar free, it’s actually quite healthy and full of dietary fibre), because it takes some effort to make. In addition, researchers have found out that self-control is a limited resource. This means that if you’ve already had to resist something several times, you’re more likely to give in the next time, because your ‘power of resistance’ has run out (Muraven et al., 1998). So it makes sense to limit the temptations that surround you.

- Prepare alternatives. It can be helpful to prepare a list of possible activities, in advance, that you can turn to as alternatives to (over)eating (e.g., if you are stressed the list could include taking a bath, reading a good book, watching your favourite series, going for a walk, or relaxation exercises like meditation or yoga).

- Keep an eye on your nutrient balance. You should have regular blood tests and, if necessary, use supplements, and make sure you are getting enough protein. A deficiency can quickly lead to loss of energy, making you feel constantly tired and leaving you without any reserves for other activities. Nutrient deficiencies can also cause fluid retention, which leads to frustration on the scales.

- Protein. Protein-rich meals make you feel fuller, and so it can be easier to deal with cravings if you can find high-protein alternatives to normal foods. Claims that a protein-rich diet places increased demands on the kidneys of healthy people have been disproved numerous times, including, for example, by Manninen (2004), who undertook a comprehensive analysis of previous studies and found no evidence of kidney or any other organ damage in people who ate twice to three times as much protein as the recommended amount. On the contrary, a high-protein diet was found to be associated with lower blood pressure and a long-term positive effect on bone density.

- A basic weight-training program. This can be done completely for free using YouTube videos, other instructional materials, or even just very basic exercises like squats and push-ups. The exercises should focus on building muscle mass, so when an exercise becomes too easy and eight to 15 repetitions are no problem to complete, they should be made harder with (extra) weights rather than by adding more repetitions. So, rather than doing 300 squats, it is better to do three sets of 12 squats while holding a 10 kg weight. It is also important to make sure you don’t exercise the same muscles every day. You should alternate training days and rest days for each muscle set. It’s during the rest days that muscles grow, and too much training can even inhibit muscle development.

- 15-minute walks. Several studies, for example those by Oh & Taylor (2012) or Ledochowski et al. (2015), have shown that 15 minutes of brisk walking is highly effective in reducing cravings for chocolate and other sweets. A 15-minute walk is not only effective for countering acute snack-attacks, but also as a preventive measure. It was found that subjects had fewer cravings for sweet things in the hours after a walk.

- Tetris. Tetris? Yes, Tetris. Skorka-Brown et al. (2014) found in their study that playing Tetris for a few minutes reduced cravings for sweet things. The researchers believe this is due to an effect called ‘elaborate intrusion’, which means that concentrating on a visual task distracts the brain so that it cannot conjure up images of sweets. If you don’t like Tetris, any other visually-based game or activity will presumably work just as well.

- Small, additional exercise routines. Short but intense efforts that quickly increase the heart rate are ideal. If you don’t have time for full exercise sessions, you can gain a lot from five to ten minutes of intense step-climbing or even jogging on the spot.

- Green tea. Quite apart from its weight-loss effects, green tea is very good for your health. It reduces blood pressure, is good for the heart, helps relieve stress and depression, strengthens the immune system, and gives you energy. It’s not a miracle cure for obesity, but this tea can help improve the basic conditions of your body.

- Water. This is the only negative-calorie foodstuff, which means it doesn’t burn infinite numbers of calories, but it is good for your health and helps prevent thirst signals from being misinterpreted as hunger signals. Apparently, a ‘mix up’ of this kind can occur because the hypothalamus (part of the brain) is responsible for regulating both appetite and thirst. Dehydration can trigger signals which are then erroneously interpreted as hunger. Alissa Rumsey, former spokesperson for the American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, says it is therefore a good idea to drink a glass of water right after you get up in the morning, and also to drink some water and then wait a few minutes whenever you have a craving. Drinking a lot can also prevent fluid retention.

- Every calorie counter needs a set of kitchen scales (available for a couple of euros) and a calorie-counting program/app. MyFitnessPal.com is one such calorie-counting program.

- Weigh yourself regularly. When and how you weigh yourself is a matter of personal preference. The only thing that’s important is to stick to a routine, because your weight can fluctuate a lot throughout the day. Personally, I like to weigh myself before I go to bed at night because I don’t want to start the day by looking at the scales, and the thought that I am about to get on the scales often prevents me from snacking in the evening. I prefer to weigh myself every day, particularly because my weight can fluctuate a lot from one day to the next. If I only weighed myself once a week and then happened to do so on a day when my weight spiked, that would bother me more than weighing myself every day and knowing that yesterday I was 1 kg lighter and so the spike must be because of fluid retention.

- Habits. Low body weight is associated with stable eating habits: in their daily lives, slim people and those who have lost a lot of weight almost always follow eating routines. This is echoed by studies that show that too much choice of food leads to overeating. Of course, that doesn’t mean that you have to live off low-fat cottage cheese and lettuce alone, but it does make a lot of sense to seek out certain foods that you like and can eat regularly.

- Habits again. Studies like the one by Neal et al. (2011) show that we eat too much out of habit, even when we don’t particularly like the food we are eating. Habitual popcorn eaters at a cinema ate stale popcorn, although they would have rejected it in any other environment. The researchers found a similar effect of eating too much when subjects ate with their dominant rather than their non-dominant hand. When we break our habits, we become more conscious of what we eat, enjoy it more, and take in fewer calories. That means it’s a good idea to change your surroundings often, eat with your non-dominant hand, lay the dinner table differently, or make any other changes to your eating habits that you can think of.

- Emotional support. The people around you might not always be supportive, so it can help to speak to people who are going through a similar process to you and have a similar view of it. Personally, I got a lot out of this Reddit site www.reddit.com/r/fatlogic. That forum inspired the title of this book and provided me with a lot of motivation in several ways. In real life, too, it can help to seek support elsewhere if your friends and acquaintances can’t provide it. So, go out and look for gym buddies — who are ideally already fitter than you are.

That final pointer 18 was also one of the reasons why I thought it absolutely imperative to write this book, and why in it I don’t only concentrate on the physical and mental mechanisms behind weight loss, but also deal extensively with the social aspects and their implications. You will probably find yourself in situations in which the people around you are not just unsupportive, but actively trying to sabotage your efforts or put obstacles in your way. One of the aims of this book is to help you recognise myths and manipulation (‘You’re not eating enough to lose weight!’). Another of the book’s aims is to offer support when the people around you are not providing it. I hope that it succeeds in these aims, and that within its pages you have found the tools necessary to conquer fat logic.