9

HOLY STONES, A CALENDAR STELE, AND FOREIGN COINS

As we have seen, there is compelling evidence that America’s giants belonged to sophisticated indigenous cultures. Along with that there are strong indications of very ancient cultural exchanges with other parts of the world. In this chapter I review reports related to tablets carved with inscriptions, a calendar stele, and ancient foreign coins.

GEORGE S. MCDOWELL REVEALS HIEROGLYPHIC TABLETS IN THE POSSESSION OF THE CINCINNATI SOCIETY OF NATURAL HISTORY

One of the most extraordinary documents I have run across in my research is a newspaper article published in 1891, which goes into a detailed description and translation of tablets in the possession of a historical society’s museum in Cincinnati, textiles matching those in Assyria, evidence of surgery, and so forth. The author was a respected writer, and the article was widely syndicated nationally in 1891.

RARE TREASURES CONTAINED IN THE MUSEUM OF THE CINCINNATI SOCIETY OF NATURAL HISTORY

BY GEORGE S. MCDOWELL

CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, JULY 15, 1891

FURTHER EXPLORATIONS NOW IN PROGRESS IN OHIO

Continued explorations among the ancient monuments remaining in the Ohio valley maintain the general interest in those people whose existence was before the time of written history, whose relations to the rest of mankind have never been discovered, and who are distinguished simply as mound builders; that is, they are known only as the authors of the most enduring of the monuments that survive them: those great piles of earth, whether raised for sacrifice, sepulture, or war.

The museum of the Cincinnati Society of Natural History is filled with a wealth of these curious peoples, in many cases inexplicable antiquities, and the explorations, which are in progress among the mounds and forts of the Little Miami Valley, under the direction of Dr. Metz, of Madisonville, Ohio, are almost every day bringing to light additions to the remarkable collection, which is equaled only by the one at the Peabody Museum, that was filled and still supplied by the same sources.

A study of these shows that the mound builders were an agricultural people, industrious in the arts of peace as well as the precautions of war, with considerable educational and scientific attainments, and that they had rites and ceremonies of religion and burial as distinctive as any that characterize the people of the present day.

ROWS AND ROWS OF GRINNING SKULLS

Illustrative of the physical characteristics of the people, the Cincinnati Museum has a number of skeletons taken from the mounds around the city and the newly-excavated cemetery near Madisonville, and there are rows upon rows of grinning skulls from which the learned members of the society have drawn many lessons touching on the mental qualifications of these ancient people.

They have determined that the shape and the phrenological points preclude the possibility to their having belonged to any Indians of whom our histories furnish us information.

There is also in the rooms of the society a piece of woven cloth taken from one of the mounds, in this case found lying close to a skeleton that occupied almost the center and bottom of the mound (so that it must have been placed there with the corpse) that in texture is almost identical with cloth found among the ruins of ancient Babylon and Assyria and the farther east.

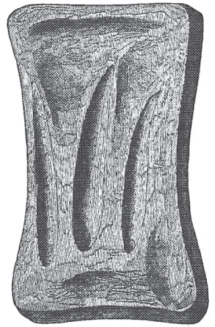

Fig. 9.1. Cincinnati tablet. Sometimes referred to as the great American Rosetta stone, the Cincinnati tablet was discovered in the Old Mound at the corner of Fifth and Mound Streets in Cincinnati in 1841. At first declared a fraud, it was later shown to be authentic. Some have speculated that it is a stylized representation of the Tree of Life. (Illustration from Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley by Ephraim Squier and Edwin Davis.)

THE SENSATIONAL CINCINNATI TABLET

Similar to the textile in its ancient connections to advanced civilization, are two other relics in the possession of the Society—one known as the “Conjuring Stone” and the other as the “Tablet of Life” or more commonly the “Cincinnati Tablet” because it was taken from one of the mounds marking the site of the city—the former a mathematical, the other a psychological witness.

The tablet is a remarkable and curious stone. Two others of similar hieroglyphical decoration, but plainly of less advanced philosophical idea, according to the learned men who examined them have been found in Ohio mounds, one near Wilmington and the other near Waverly.

And not only does the Cincinnati Tablet exhibit a more advanced idea, it is also of superior workmanship and preservation. An examination of the drawing of the Cincinnati Tablet will discover upon it several fetal designs that have been interpreted as symbolical of those gestative and procreative mysteries that must have powerfully affected the minds of man in the remotest early ages. The design of the tablet shows that its author had knowledge of the stages of development at various periods of fetal growth, and the tablet, bearing these symbolizations of the existence before life, was no doubt used in connection with the ceremonies of sepulture and possibly by way of comparative conjecture concerning the hidden things of life beyond the grave.

THE MEASURING STONE

Regarding the next in importance to the “Tablet,” is the “Measuring Stone.” This is a piece of sandstone, about exactly nine inches on the flat side and twelve inches on the curve, the dotted lines in the drawing indicating the completed ellipse, which is an exact model of the mound in which it was found.

Learned mathematical analysis shows this stone to have been the basis for all measurements of the great mounds and earthworks in the Ohio Valley, and that the same numbers 9 and 12 are the key numbers of the measures used in the construction of the architectural works of the Chaldeans, Babylonians, pre-Semites, and Egyptians, while the latter number remains to this day the English standard.

EVIDENCE OF BRAIN SURGERY

The skull taken from an excavation near Cincinnati shows that these people were well-versed in surgery. It is the skull of a man who had once received a terrible blow to the side of the head, which crushed the skull, but after careful treatment recovered from the effects of the blow. Dr. Langdon, an eminent surgeon of Cincinnati, examined the skull and said that the adjustments to the parts of bone and the way in which they had healed show knowledge of practical surgery scarcely excelled at the present day.

FORGES, POLISHING BONES, AND IRON

The relics in the Museum of the Cincinnati Society show also that these people were well-versed in the industrial arts, there being the remains of hammers, knives, mica ornaments, beads, wampum, decorated shells, pottery, and many other things. Among these are some that have puzzled the scientists to determine to what uses they have been applied such as a certain leg bone.

It is a femur almost worn in two by some friction, as though it must have been used for polishing. Thousands of pieces of these bones have been found, having been so worn away that they broke in use.

There is also a kind of needle, made from long fish bones resembling in length the present crocheting needle and the carpet needle in construction. They may have been used in the making of clothing.

There are found the remains of forges, and great quantities of furnace slag and cinders and scaling like those that fly from beaten white-hot iron.

HIEROGLYPHICS ALSO FOUND IN MARIETTA

It may be that one of the tablets with “similar hieroglyphical decoration” referred to by McDowell in 1891 is the one described below as part of the findings of an elaborate giant burial in Muskingum County, Ohio.

REMAINS OF NINE-FOOT GIANTS IN OHIO

CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, JULY 14, 1880

(SEE MARION DAILY STAR, JULY 14, 1880, FOR ORIGINAL STORY)

The mound in which these remarkable discoveries were made was about sixty-four feet long and thirty-five feet wide top measurement and gently sloped down to the hill where it was situated. A number of stumps of trees were found on the slope standing in two rows, and on the top of the mound were an oak and a hickory stump, all of which bore marks of great age.

All of the skeletons were found on a level with the hill, and about eight feet from the top of the mound. In one grave there were two skeletons, one male and one female. The female face was looking downward, the male being immediately on top, with the face looking upward. The male skeleton measured nine feet in length, and the female was eight.

The male frame in this case was nine feet, four inches in length and the female was eight feet.

In another grave was found a female skeleton, which was encased in a clay coffin, holding in her arms the skeleton of a child three and a half feet long, by the side of which was an image, which being exposed to the atmosphere, crumbled rapidly.

The remaining seven, were found in single graves and were lying on their sides. The smallest of the seven was nine feet in length and the largest ten. One single circumstance connected with this discovery was the fact that not a single tooth was found in either mouth except in the one encased in the clay coffin.

On the south end of the mound was erected a stone altar, four and a half feet wide and twelve feet long, built on an earthen foundation nearly four feet wide, having in the middle two large flagstones, from which sacrifices were undoubtedly made, for upon them were found charred bones, cinders, and ashes. This was covered by about three feet of earth.

AN ANCIENT TABLET WITH POSSIBLE HIEROGLYPHS

What is now a profound mystery may in time became the key to unlock still further mysteries that were centuries ago commonplace affairs.

I refer to a stone that was found resting against the head of the clay coffin above described. It is irregularly shaped red sandstone, weighing about 18 pounds, being strongly impregnated with oxide of iron, and bearing upon one side TWO LINES OF HIEROGLYPHS.

HOLY STONES IN OHIO AND ILLINOIS?

Other ancient engraved tablets found in Ohio and Illinois deepen the mystery.

IS IT REALLY THE TEN COMMANDMENTS?

OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY WEB ARCHIVE

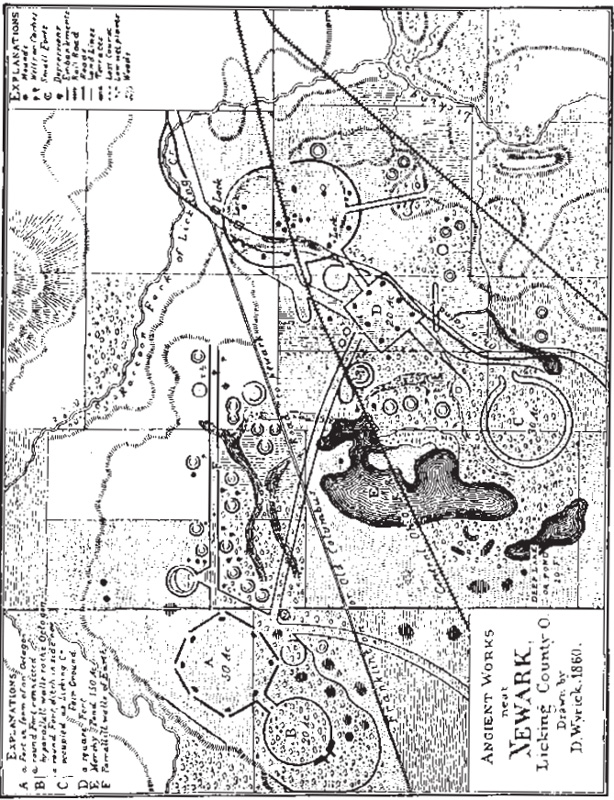

In November of 1860, David Wyrick of Newark, Ohio, found an inscribed stone in a burial mound about ten miles south of Newark. The stone is inscribed on all sides with a condensed version of the Ten Commandments or Decalogue, in a peculiar form of post- Exilic square Hebrew letters. The robed and bearded figure on the front is identified as Moses in letters fanning over his head.

The inscription is carved into a fine-grained black stone. It has been identified by geologists Ken Bork and Dave Hawkins of Denison University as limestone; a fossil crinoid stem is visible on the surface, and the stone reacts strongly to HCl. It is definitely not black alabaster or gypsum as previously reported here. According to James L. Murphy of Ohio State University, “Large white crinoid stems are common in the Upper Mercer and Boggs limestone units in Muskingum Co. and elsewhere, and these limestones are often very dark gray to black in color. You could find such rock at the Forks of the Muskingum at Zanesville, though the Upper Mercer limestones do not outcrop much further up the Licking.” We therefore need not look any farther than the next county over to find a potential source for the stone, contrary to the previous assertion here that such limestone is not common in Ohio. The inscribed stone was found inside a sandstone box, smooth on the outside and hollowed out within to exactly hold the stone. The Decalogue inscription begins at the non-alphabetic symbol at the top of the front, runs down the left side of the front, around every available space on the back and sides, and then back up the right side of the front to end where it begins, as though it were to be read repetitively.

Fig. 9.2. The Newark “holy stone” (courtesy of J. Huston McCulloch)

David Deal and James Trimm note that the Decalogue stone fits well into the hand, and that the lettering is somewhat worn precisely where the stone would be in contact with the last three fingers and the palm if held in the left hand. Furthermore, the otherwise puzzling handle at the bottom could be used to secure the stone to the left arm with a strap. They conclude that the Decalogue stone was a Jewish arm phylactery or tefilla (also written t’filla) of the Second Temple period. Although the common Jewish tefilla does not contain the words of the Decalogue, Moshe Shamah reports that the Qumran sect did include the Decalogue.

THE KEYSTONE ALSO FOUND AT NEWARK MOUNDS

Several months earlier, in June of 1860, David Wyrick had found an additional stone, also inscribed in Hebrew letters. This stone is popularly known as the “Keystone” because of its general shape. However, it is too rounded to have actually served as a keystone. It was apparently intended to be held with the knob in the right hand, and turned to read the four sides in succession, perhaps repetitively. It might also have been suspended by the knob for some purpose. Although it is not pointed enough to have been a plumb bob, it could have served as a pendulum.

The material of the Keystone has been identified, probably by geologist Charles Whittlesey, immediately after its discovery as novaculite, a very hard fine-grained siliceous rock used for whetstones. [For more on Whittlesey, see “Ancient Copper Mining in the Great Lakes,”.] The inscriptions on the four sides read:

Fig. 9.3. The Keystone (courtesy of J. Huston McCulloch)

- Qedosh Qedoshim, "Holy of Holies"

- Melek Eretz, "King of the Earth"

- Torath YHWH, "The Law of God"

- Devor YHWH, "The Word of God"

Wyrick found the Keystone within what is now a developed section of Newark, at the bottom of a pit adjacent to the extensive ancient Hopewellian earthworks there (circa 100 BC–AD 500). Although the pit was surely ancient, and the stone was covered with 12–14 inches of earth, it is impossible to say when the stone fell into the pit. It is, therefore, not inconceivable that the Keystone is genuine but somehow modern.

The letters on the Keystone are nearly standard Hebrew rather than the very peculiar alphabet of the Decalogue stone. These letters were already developed at the time of the Dead Sea Scrolls (ca. 200–100 BC), and so are broadly consistent with any time frame from the Hopewellian era to the present. For the past 1000 years or so, Hebrew has most commonly been written with vowel points and consonant points that are missing on both the Decalogue and Keystone. The absence of points is therefore suggestive, but not conclusive, of an earlier date.

Note that in the Keystone inscription, “Melek Eretz,” the aleph and mem have been stretched so as to make the text fit the available space. Such dilation does occasionally appear in Hebrew manuscripts of the first millennium AD. Birnbaum, The Hebrew Scripts, vol. I, pp. 173–4, notes that “We do not know when dilation originated. It is absent in the manuscripts from Qumran. . . . The earliest specimens in this book are . . . middle of the seventh century [AD]. Thus we might tentatively suggest the second half of the sixth century or the first half of the seventh century as the possible period when dilation first began to be employed.” Dilation would not have appeared in the printed sources nineteenth-century Ohioans would primarily have had access to.

The Hebrew letter shin is most commonly made with a V-shaped bottom. The less common flat-bottomed form that appears on the first side of the Keystone may provide some clue as to its origin. The exact wording of the four inscriptions may provide additional clues.

Today, both the Decalogue Stone and Keystone, or “Newark Holy Stones,” as they are known, are on display in the Johnson-Humrickhouse Museum in Roscoe Village, 300 Whitewoman St., Coshockton, Ohio.

THE WILSON MOUND STONES

One year after Wyrick’s death in 1864, two additional Hebrew-inscribed stones were found during the excavation of a mound on the George A. Wilson farm east of Newark. These stones have been lost, but a drawing of the one and a photograph of the other are reproduced in Alrutz.

The two stones from the Wilson farm, known as the “Inscribed Head” and the “Cooper Stone” at first caused considerable excitement. Shortly afterwards, however, a local dentist named John H. Nicol claimed to have carved the stones and to have introduced them into the excavation, with the intention of discrediting the two earlier stones found by Wyrick.

The inscription on the Inscribed Head can be read in Hebrew letters as J–H–NCL.In Hebrew, short vowels are not represented by letters, so this is precisely how one would write J–H–NiCoL.

The Cooper stone is less clear, but appears to have a similar inscription. The inscriptions themselves therefore confirm Nicol’s claim to have planted these two stones. Nicol was largely successful in his attempt to discredit the Wyrick stones, and they quickly became a textbook example of a “well-known” hoax. It was only with Alrutz’s thorough 1980 article*3 that interest in them was revived.

Although the Decalogue is of an entirely different character than either of the Wilson Mound stones, it is disturbing that Nicol was standing near Wyrick at the time of its discovery.

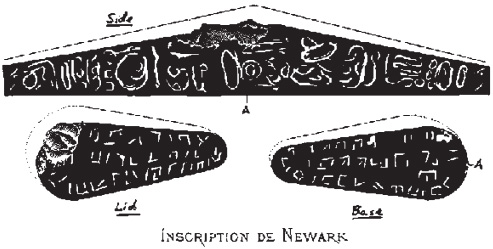

THE JOHNSON-BRADNER STONE

Two years later, in 1867, David M. Johnson, a banker who co-founded the Johnson-Humrickhouse Museum, in conjunction with Dr. N. Roe Bradner, M.D., of Pennsylvania, found a fifth stone, in the same mound group south of Newark in which Wyrick had located the Decalogue. The original of this small stone is now lost, but a lithograph, published in France, survives.

The letters on the lid and base of the Johnson-Bradner stone are in the same peculiar alphabet as the Decalogue inscription, and appear to wrap around in the same manner as on the Decalogue’s back platform. However, the lithograph is not clear enough for me to attempt a transcription with any confidence. However, Dr. James Trimm, whose Ph.D. is in Semitic Languages, has recently reported that the base and lid contain fragments of the Decalogue text. The independent discovery, in a related context, by reputable citizens, of a third stone bearing the same unique characters as the Decalogue stone, strongly confirms the authenticity and context of the Decalogue Stone, as well as Wyrick’s reliability.

Fig. 9.4. Ancient Works at Newark. This map was published in the1866 Newark County Atlas.

Fig. 9.5. These skeletons found in a recent excavation in Germany are from the Neolithic Period and are typical of the multiple burials found in many of America’s Indian mounds (courtesy of Arthur W. McGrath).

Fig. 9.6. Lithograph by Nancy J. Royer, Congres International des Americanistes (courtesy of J. Huston McCulloch)

Mr. Myron Paine of Martinez, Calif., has cogently noted that the Johnson-Bradner stone, if bound in a strap so as to be held as a frontlet between the eyes, would serve well as a head phylactery, while the Decalogue stone was being used as an arm phylactery per the Deal-Trimm hypothesis noted in the first section above.

THE MYSTERIOUS STONE BOWL

A stone bowl was also found with the Decalogue, by one of the persons accompanying Wyrick. By Wyrick’s account, it was of the capacity of a teacup, and of the same material as the box. Wyrick believed both the box and the cup had once been bronzed (Alrutz, pp. 21–2), though this has not been confirmed. The bowl was long neglected, but was found recently in the storage rooms of the Johnson-Humrickhouse Museum by Dr. Bradley Lepper of the Ohio Historical Society. It is now on display along with the Decalogue stone and Keystone. (Photo courtesy of Jeffrey A. Heck, Najor Productions, njor@tcon.net).

An interview in the Jan/Feb 1998 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review (“The Enigma of Qumran,” pp. 24ff.) sheds light on the possible significance of the stone bowl. The interviewer, Hershel Shanks, asked how we would know that Qumran, the settlement adjacent to the caves in which the Dead Sea Scrolls were found, was Jewish, if there had been no scrolls. The four archaeologists interviewed gave several reasons: the presence of ritual baths, numerous Hebrew-inscribed potsherds, and its location in Judea, close to Jerusalem. Then Hanan Eshel, senior lecturer in archaeology at Hebrew University and Bar-Ilan University, gave a fourth reason.

Fig. 9.7. The Decalogue stone, the Keystone, and the ritual cleansing bowl (photo by Jeffrey A. Heck)

ESHEL: We also have a lot of stone vessels.

SHANKS: Why is that significant?

ESHEL: Stone vessels are typical of Jews who kept the purity laws. Stone vessels do not become impure.

SHANKS: Why?

ESHEL: Because that is what the Pharisaic law decided. Stone doesn’t have the nature of a vessel, and therefore it is always pure.

SHANKS: Is that because you don’t do anything to transform the material out of which it is made, in contrast to, say, a clay pot, whose composition is changed by firing?

ESHEL: Yes. Probably. Stone is natural. You don’t have to put it in an oven or anything like that. Purity was very important to the Jews in the Late Second Temple period.

In an article in a subsequent issue of BAR, Yitzhak Magen goes on to explain that in the late Second Temple period, the Pharisees ordained that observant Jews should ritually rinse their hands with pure water before eating, and that in order to be pure, the water had to come from a pure vessel. Pottery might be impure, but stone was always pure. The result was a brief “Israeli Stone Age,” during which there flourished an industry of making stone teacups to pour the water from and stone jugs to store it in. After the destruction of the Second Temple in AD 70, this practice quickly disappeared.

The stone bowl therefore fits right in with the Decalogue Stone as an appropriate ritual object. It is highly doubtful that Wyrick, Nicol, McCarty, or anyone else in Newark in 1860 would have been aware of this arcane Second Temple era convention.

Perhaps the stone box is another manifestation of the same “Stone Age” imperative: The easy way to make a box to hold an important object (or a prank) is out of wood. Carving it from stone is unnecessarily difficult, and would be justified only if stone were regarded as being significant in itself. According to Wyrick the bowl and box were made of the same sandstone.

Two unusual “eight-square plumb bobs” were also found with the Decalogue. Their location is unknown, though they might also turn up in the Museum’s collections.

HUNTERS FIND STONE TABLETS UNDER A TREE

SMITHSONIAN INVOLVED IN ILLINOIS TABLET FIND

A REMARKABLE FIND ON THE PRAIRIES OF ILLINOIS: QUAINT LETTERING, INDIAN RELICS, AND THE MOUND BUILDERS

CHICAGO TRIBUNE, AUGUST 10, 1892

A remarkable discovery was recently made on the virgin field a few miles from LaHarpe, in the historic old county of Hancock, in Illinois. Wyman Huston and Daniel Lovitt were chasing a ground squirrel on the farm of Huston, when the dog trailed the squirrel to its hole under an old dead tree stump, which was easily pushed over by one of the men. In grabbing for the squirrel, the old stump was taken out, and under its roots were found two sandstone tablets, about 10 × 11 inches, and from one-fourth to half-an-inch in thickness.

The tablets lay one upon the other, and the sides that faced contained strange inscriptions in Roman-like capital letters that had been cut into the stone with some sharp instrument. The men brought the tablets to LaHarpe, where they were inspected by several antiquarians but none of them could decipher the inscriptions. Mr. Huston allowed the stones to be forwarded to the Smithsonian in Washington D.C., where they are to be held for scientific investigation.

SMITHSONIAN BAFFLED BY INSCRIPTIONS

The authorities of the Smithsonian Institution state that the find is a remarkable one, and that they hope to throw some light upon the meaning of the lettering etched upon the tablets. But, so far, however, they have been unable to do so, or at least they have not announced the result of any discoveries, they may have made in the matter.

THE DAVENPORT STELE

When the Davenport Stele is added to the mix, things get even stranger. The stele was found in an Indian mound in 1877, and according to Harvard Professor Barry Fell, the stele contains writing in Egyptian, Iberian-Punic, and Libyan. The Smithsonian, of course, says it and others like it are fakes.

SMITHSONIAN INVOLVED IN STRANGE ANCIENT IOWA TABLET “HOAX” WITH AMERICA B.C.’S BARRY FELL

BY OTTO KNAUTH

DES MOINES REGISTER, FEBRUARY 20, 1977

“Egyptian and Libyan explorers sailed up the Mississippi River 2,500 years ago and left a tablet where Davenport now stands,” a Harvard Professor said. “That’s absurd,” countered a former Iowa state archeologist, who says the Professor is perpetuating a 100-year-old hoax. Harvard’s Dr. Barry Fell, a marine biologist by profession and an epigraphist by avocation, said he had deciphered the front and back of a table that was found in an Indian mound in 1877. “The tablet,” he stated, “contains writing not only in Egyptian hieroglyphics but also in Iberian-Punic and Libyan.”

He likened it in importance to the famed Rosetta Stone, which, because it said the same thing in three languages, enabled scientists to decipher hieroglyphics.

“It is unquestionably genuine,” he stated.

“Not so,” said University of Iowa archeologist Marshall McKusick. “The tablet is part of ‘one of the most thoroughly documented hoaxes in American archeology.’ Members of the old Davenport Academy of Science inscribed the tablets and buried them in a mound on the old Cook farm, knowing the tablets would be found by a member they wanted to ridicule,” McKusick says.

But the hoax got out of hand when the Smithsonian Institution got involved and the discovery of the tablets received national publicity. McKusick documented the hoax in a 1970 book, The Davenport Conspiracy.

“That all may well be true,” Fell said in a recent telephone interview, “and two of the three tablets in the mound probably are fake. But the third, which he refers to as the Davenport Calendar Stele, definitely is not.” This stele with the spring equinox scene on is described in Barry Fell’s book, America B.C., as “one of the most important ever discovered. It is used in the ceremonial erection of a New Year pillar made of bundles of reeds called ‘Djed,’” Fell said.

“Writing in the curving lines above says the same thing in Iberian and Libyan. The Egyptian hieroglyphics along the top explain how to use the stone.

“Two Indian pipes carved in the shape of elephants found in the mound also are genuine,” Fell says.

BARRY FELL PUBLISHES CONTROVERSIAL AMERICA B.C.

Fell’s account of deciphering the tablet and the implications of its message are contained in his book just published, America B.C.: Ancient Settlers in the New World. The book deals with a wide variety of finds, particularly in New England, but also ranging as far west as Oklahoma, which Fell contends prove that ancient Egyptians, Libyans, Celts, and other people were able to reach America and settle here well before the birth of Christ. Portions of the book are reprinted in the February issue of Reader’s Digest. “The Davenport stele,” Fell writes, “is the only one on which occurs a trilingual text in the Egyptian, Iberian-Punic, and Libyan languages.

“This stele, long condemned as a meaningless forgery, is in fact one of the most important steles ever discovered,” he writes.

“One side of the tablet—since its discovery it has separated by cleavage so that each face is now separate—depicts the celebration of the Djed Festival of Osiris at the time of the Spring equinox (Mar. 21),” Fell says. The other side contains the corresponding fall hunting festival at the time of the autumnal equinox (Sept. 21). The writing runs along the top of the spring tablet. “The Iberian and Libyan texts,” Fell says, “both say the same thing—that the stone carries an inscription giving the secret of regulating the calendar.” This “secret” is given in the Egyptian text of hieroglyphics.

“This Egyptian text,” Fell says, “may be rendered in English as follows”:

To a pillar attach a mirror in such a manner that when the sun rises on New Year’s Day it will cast a reflection onto the stone called the Watcher. New Year’s Day occurs when the sun is in conduction with the zodiacal constellation Aries, in the House of the Ram, the balance of night and day being about to reverse. At this time (the spring equinox) hold the Festival of the New Year and the Religious Rite of the New Year.

“This festival,” Fell says, “consists in the ceremonial erection of a special New Year pillar made of bundles of reeds called a “djed.” The tablet, shows long lines of worshippers pulling on ropes with the pillar in the center.”

HOW DID ANCIENT HIEROGLYPHS GET TO IOWA?

“How did this extraordinary document come to be in a mound burial in Iowa?” Fell asks. “Is it genuine?

“Certainly it is genuine,” he says, “for neither the Libyan nor the Iberian scripts had been deciphered at the time Gass [Rev. Jacob Gass] found the stone. The Libyan and Iberian texts are consistent with each other and with the hieroglyphic text.

“As to how it came to be in Iowa, some speculations may be made. The stele appears to be of local American manufacture, perhaps made by a Libyan or an Iberian astronomer who copied as an older model brought from Egypt or more likely from Libya, hence probably brought on a Libyan ship.

“The Priest of Osiris may have issued the stone originally as a means of regulating the calendar in far distant lands. The date is unlikely to be earlier than about 800 B.C., for we do not know of Iberian or Libyan inscriptions earlier than that date,” Fell writes.

“The explorers presumably sailed up the Mississippi River and colonized in the Davenport area,” he says, and he hazards a guess that they came on ships commanded by a Libyan skipper of the Egyptian navy, during the Twenty-second, or Libyan, Dynasty, a period of overseas exploration. “An Egyptian astronomer-priest probably came with the explorers,” he speculates, “and it was he or his successors who engraved the stone.

“The hunting scene tablet is engraved in Micmac script and is the work of an Algonquian Indian of about 2,000 years ago,” Fell says. He does not explain the discrepancy in time, but goes on to say that the Algonquian culture shows evidence of contact with early Egyptians. The approximate translation is:

Hunting of beasts and their young, waterfowl and fishes. The herds of the Lord and their young, the beasts of the Lord.

“It is the earliest known example of Micmac script,” Fell says. Fell makes no mention in his book of McKusick’s account of the Davenport fraud but this is not because he was not aware of it.

AVOIDING OLD DISPUTES

“I just felt it was kinder not to mention it,” he said recently. “It was my desire to avoid raking up old disputes. Who cares whether somebody defrauded somebody else a hundred years ago? I attach no importance to those things.”

NINETY-FIVE-PERCENT OF “FRAUDS” TURN OUT TO BE TRUE

The Smithsonian, which was the first to declare the tablets fraudulent, had no experts in ancient languages. “Only those who thought they were,” Fell said.

“And McKusick himself makes no claim to being a linguist,” he says. Fell said he has been investigating similar archeological finds that had been labeled frauds, “and we find that 95 per cent of them are genuine.

“There is a tendency on the part of those established in a field of science either to ignore or label as fraud anything that does not fit in with their pre-conceived notion of how things should be,” he said.

“It is much easier to cry fraud at something out of the ordinary than to investigate it,” he said. “Americans are throwing away 2,000 years of their history that way.”

Fell concedes he has never been in Iowa and was not allowed to see the tablet, which is now in possession of the Putnam Museum in Davenport. He says he did his deciphering from photographs, which is the usual way epigraphists do their work. McKusick has taken up the challenge by writing a report to Science, the weekly publication of the prestigious American Academy for the Advancement of Science. He said the Davenport frauds were first exposed in Science in the 1880s and later reviewed in 1970. McKusick pointed out that the slate for one of the tablets (not Fell’s Davenport stele) came from a wall of the Old Slate House, a notorious early-day house of ill fame. “The third tablet, a piece of limestone with a tablet, is engraved on a piece of slate,” said University of Iowa Archeologist Marshall McKusick.

In 1970 McKusick wrote a book about the Davenport Conspiracy that surrounded the finding of the tablets in an Indian mound in 1877. “Holes diameter and were used to hang the slate,” McKusick says. Fell concedes this tablet may well have a fake figure of an Indian on it and came from Schmidt’s Quarry, not far from the place where the tablets were found. The farm site now is occupied by the Thompson-Hayward Chemical Co., 2040 West River Drive.

“A dictionary and almanacs provided inspiration for the writing on the tablets,” he said. “A janitor at the Academy admitted carving various Indian pipes, which also were found in the mound,” McKusick said. “They were soaked in grease or rubbed with shoe black to make them look old.” Two members of the academy were expelled in the ruckus that followed the claims of fraud but a curious sidelight to the controversy lies in the fact that none of the participants ever admitted in writing that they actually forged the tablets. All were under threat of libel at the time. The closest thing to a confession in McKusick’s book is a statement by Judge James Bellinger made in 1947 to a Mr. Irving Hurlbut. In it, Bellinger tells of copying hieroglyphics out of old almanacs on slate he tore off the wall of the Old Slate House.

The story becomes suspect, however, when McKusick points out that Bellinger was only 9 years old at the time the tablets were found. “Whatever the judge may have said, he was nowhere near the scene of the events he so vividly describes,” McKusick wrote.

“GULLIBLE PUBLIC”

In his report to Science McKusick says of the Fell book: “It is an unfortunate imposition upon a gullible public to have the Davenport frauds accepted as genuine and used to explain Egyptian explorations up the Mississippi 3,000 years ago.

“Fell, as a ‘Harvard scholar,’ has a scholarly responsibility to know the professional literature on subjects he is publishing theories about. His book, America B.C., is irresponsible amateurism and is unfortunately but one example of a genre of speculation that is growing and sells well to the public.”

“Modern technology may provide the means for resolving the issue of whether one or all of the tablets are fake,” says Dr. Duane Anderson, who succeeded McKusick as state archeologist. “If the tablets could be submitted to a rigorous microscopic examination, it might be possible to determine that the writing is older than a mere 100 years,” Anderson said. “Rock ages, and often a patina, or microscopic crust, develops on the surface. It might also be possible to detect traces of modern steel if the incisions were made with modern instruments,” he said. Anderson continued, “But they might at least be able to reveal if the writing was done before 1877.”

Anyone wishing to make such an examination will have to secure the cooperation of the Putnam Museum, which is the present custodian of the tablets. Museum Director Joseph Cartwright has steadfastly refused access to the tablets, saying they have “been removed from the museum collection.

“We are not anxious to dig up the whole controversy again,” he said in a recent telephone interview. “It is not in the museum’s interest to make them available. This is something the museum is not interested in.” Asked if it might not be interesting for the public to put the tablets on display in view of the present renewal of the controversy, Cartwright replied, “It is our prerogative to decide, not yours.”

HIEROGLYPHIC TABLETS IN MICHIGAN AND KENTUCKY

Evidence of writing and hieroglyphs has been found all over the country, attesting to widespread trade and wide-ranging cultural influences. Many examples have been found in Michigan, including the controversial Michigan tablets, which number in the thousands. Many more finds of writing have been discovered across the country, although many, like the Ten Commandments from Ohio and the Michigan and Illinois tablets, are still under hot dispute. Here are two finds from Michigan and Kentucky that appear genuine.

ANCIENT HIEROGLYPHICS AND WRITING ON A TABLET

DETROIT FREE PRESS, JUNE 14, 1894

The mounds on the south side of Crystal Lake, in Montcalm County, Michigan, have been opened and a prehistoric race unearthed. One contained five skeletons and the other three. In the first mound was an earthen tablet five inches long, four wide, and half as much thick. It was divided into four corners. On one of them were inscribed queer characters. The skeletons were arranged in the same relative positions, so far as the record is concerned.

In the other mound, there was a casket of earthen ware ten and one half inches long and three and a half inches wide. The cover bore various inscriptions. The characters found upon the tablet were also prominent on the casket. Upon opening the casket, a copper coin was revealed, together with several stone types, with which the inscriptions or casket had evidentially been made. There were also two pipes—one of stone, the other of pottery and apparently of the same material as the casket.

STRANGE ANCIENT WELSH MESSAGE WRITTEN ON A STONE?

PROCEEDINGS OF THE ANCIENT KENTUCKY HISTORICAL SOCIETY, FEBRUARY 11, 1880

Craig Crecelius made a curious discovery in 1912, while plowing his field in Meade County, Kentucky. He had unearthed a limestone slab that had strange symbols chiseled onto the rock face. Knowing that he had made an important historical find, he sought information about the origins of the stone from the academics.

For over 50 years, Crecelius inquired of anyone with academic credentials about the significance of the carved symbols. Typical of the comments he received from the “experts” were like what one geologist in 1973 remarked that the rock was “geologic in origin” and “not an artifact.” An archaeologist has said that the carvings were grooves created by shifting limestone pressures.

Disheartened and tired of being made fun of by the locals, Crecelius finally gave up his quest for finding out the rock’s secrets. In the mid1960s, he allowed Jon Whitfield, a former trustee of the Meade County, Kentucky, Library, to display the stone in the Brandenburg Library. This could very well have been the end of the story, had it not been for the observant Mr. Whitfield.

Whitfield attended a meeting of the Ancient Kentucky Historical Society (AKHS) and saw slides of other, similar-looking carved stones. He learned that the carvings were a script called Coelbren, used by the ancient Welsh. Whitfield was informed that similar stones had been widely found across the south-central part of the U.S. Pictures made of the Brandenburg Stone were submitted to two Welsh historians helping the AKHS in deciphering the scripts.

Alan Wilson and Baram Blackett, specialists in the study of the Coelbren script in Wales, immediately were able to read the script. The translation is intriguing; it appears that the stone may possibly have been a property or boundary marker: “Toward strength, divide the land we are spread over, purely between offspring in wisdom.”

Wilson and Blackett place a connotation of the promotion of unity with the phrase “Toward strength” and a connotation of justice with the word “purely.” The stone was on public display from 1999–2000 at the Falls of the Ohio State Park Interpretive Center in Clarksville, Indiana. The display has since been moved to the Charlestown Public Library, Clark County, Indiana.

ANCIENT COINS FOUND IN AMERICA

Scattered reports of ancient coins found buried around the country are usually dismissed as fraudulent by traditional archaeologists, but in the collection of stories that follow, one outlines a circumstance where the difficulty of creating a hoax belies that idea, while others tell of quite recent finds that have been authenticated by ancient coin experts.

The following first-person account of the discovery of two ancient coins is very instructive. The coins were found underneath the roots of a beech tree that had been blown up in order to clear a field. This is not something that could be done as a prank, as the entire operation would have been costly and pointless in the extreme.

The Natural and Aboriginal History of Tennessee, 1823

BY DR. JOHN HAYWOOD

A Copper Medal of King Richard III Found

Between the years of 1802 and 1809, in the state of Kentucky, Jefferson County, on Big Grass Creek, which runs into the Ohio River at Louisville, at the upper end of the falls, about ten miles above the mouth, near Middleton, Mr. Spear found under the roots of a beech tree, which had been blown up, two pieces of copper coin of the size of our old copper pence. On one side was represented an eagle with three heads united to one neck. The sovereign princes of Greece wore on their scepters the figure of a bird and often that of an eagle. Possibly this may have been a coin uttered in the time of the three Roman emperors.

Lately, a Cherokee Indian delivered to Mr. Dwyer, in the year 1822, who delivered to Mr. Earle, a copper medal, nearly or quite the size of a dollar. All around it, on both sides was a raised rim. On the one side is the robust figure of a man, apparently of the age of 40, with a crown upon his head, buttons upon his coat, and a garment flowing from a knot on his shoulder, toward and over the lower part of his breast, his hair short and curled; his face full; his nose aquiline, very prominent and long, the tip descending very considerably below the nostril; his mouth wide; the chin long, and the lower part very much curved, and projected outwards. Within the rim, which is on the margin, and just below it in Roman letters, are the words and figures: “Richardus III. DG. ANG. FR. Et HIB. Rex.” The letters are none of them at all worn. Both the letters and figures protuberated from the surface. On the other side is a monument with a female figure reclined on it, her knees a little raised, with a crown upon them, and in her left hand a sharp pointed sword. Underneath the monument are the words: “Coronat 6h Jul, 1483.” And under that line: “Mort 22 Aug. 1485.”

Of Their Coins and Other Metals

About the year 1819, in digging a cellar at Mr. Norris’s, in Fayetteville, on Elk river, which falls into Tennessee, and about two hundred yards from a creek, which empties into Elk, and not far from the ruins of a very ancient fortification on the creek, was found a small piece of silver coin of the size of a nine-penny piece.

On the one side of this coin is the image of an old man projected considerably from the superficies with a large Roman nose, his head covered apparently with a cap of curled hair; and on this side on the edge in old Roman letters, not so neat by far as on our modern coins, are the words: “Antoninus Aug: Pius. PP. RI. Ill cos.”

On the other side the projected image of a young man, apparently 18 or 20 years of age; and on the edge: Juleiius Ceasar. AL/GP, 111.cos.” It was coined in the third year of the reign of Antoninus, which was in the year of our Lord 137, and must in a few years afterwards have been deposited where it was lately found. The prominent images are not in the least impaired, nor in any way defaced, nor made dim or dull by rubbing with other money; neither are the letters on the edges. It must have lain in the place where lately found, 1500 or 1600 years.

For had it first circulated a century, before it was laid up, the worn-off parts of the letters and images would be observable. It was found five feet below the surface. The people living upon Elk River when it was brought into the country had some production of art, or of agriculture, for which this coin was brought to the place, to be exchanged. It could not have been brought by De Soto, for long before his time it would have been defaced and made smooth by circulation; and, besides, the crust of the earth would not have been increased to the depth of five feet in 177 years, the time elapsed since De Soto passed between the Alabama and the Tennessee, to the Mississippi.

Irrefutable Proof of Commerce by Sea

This coin furnishes irrefragable proof of one very important fact; namely, that there was an intercourse, either by sea or by land, between the ancient inhabitants of Elk River, and the Roman Empire in the time of Antoninus, or soon afterwards; or between the ancient Elkites, and some other nation, who had such intercourse with it. Had a Roman fleet been driven by a storm, in the time of Antoninus, on the American shores, the crews, even if they came to land all at the same place, would not have been able to penetrate to Elk river, nor would any discoverable motive have engaged them to do so.

And again: Roman vessels, the very largest in the Roman fleet of that day, were not of structure and strength sufficient to have lived in a storm of such violence and long continuance in the Atlantic ocean, as was necessary to have driven them from Europe to America. Nor are storms in such directions and of such continuance at all usual. Indeed, there is no instance of any such, which has occurred since the European settlements in America.

The people of Elk in ancient times did probably extend their commerce down the rivers that Elk communicated with; or if directly over land to the ocean, they were not impeded by small, independent tribes between them and the ocean but were part of an empire extended to it. A thick forest of trees, not more than 6 or 8 years ago, grew upon the surface where the coin was found, many of which could not be of more recent commencement than 300 or 400 years; a plain proof that the coin was not of Spanish or French importation.

Besides this coin impressed with the figures of Antoninus and Aurelius, another was also found in a gully washed by torrents about two and a half miles from Fayetteville, where the other coin was found. It was about four feet below the surface. The silver was very pure, as was also the silver of the other piece; evidently much more so than the silver coins of the present day.

The letters are rough. Some of them seem worn. On the one side is the image of a man, in high relief, apparently of the age of 25 or 30. And on the coin, near the edge were these words and letters: Commodus. The C is defaced, and hardly visible. AVG. HEREL, on the other side, f E. IMP. III. cos. H. PP. Oa rx. This latter side also is the figure of a woman, with a hoop in her right hand. She is seated in a square box; on the inside of which, touching each side, and resting on the ground, is a wheel. Her left arm, from the shoulder to the elbow, lies by her side, but from the elbow is raised a little above the top: and across a small distaff, proceeding from the hand, is a handle to which is added a trident with the teeth or prongs parallel to each other. It is supposed that Faustina, the mother of Commodus, who was defied after her death by her husband Marcus Aurelius, with the attributes of Venus, Juno, and Ceres, is represented by this figure.

The neck of Commodus is bare, with the upper part of his robes flowing in gatherings from the lower part of the neck. His head seemed to be covered with a cap of hair curled into many small knots, with a white fillet around it, near its edges, and the temples and forehead, with two ends falling some distance from the knot. Commodus reigned with his father, Marcus Aurelius, from the time he was 14 or 15 years of age, until the latter died, in the year of our Lord 180. From that time he reigned alone, until the 31st of December, 192, when he was put to death.

A HALF-SILVER-DOLLAR-SIZED SCENE OF HOUND AND DEER

Also from Haywood’s book, here is a separate report from Lincoln, Tennessee, which is about eleven miles from the Fayetteville site, in which a silver medallion was discovered with the image of a deer being chased by a hound engraved on one side. More than thirty-five similar medallions were plowed up three miles from this site on a farm owned by a Mr. Oliver Williams.

The Natural and Aboriginal History of Tennessee, 1823

BY DR. JOHN HAYWOOD

Lincoln County, in West Tennessee, is eleven miles from Fayetteville, where the Roman coin above mentioned was found, and near to the mouth of Cold water creek, and about 600 yards distant from the river. The button is about the size of a half dollar in circumference and is of the intrinsic value of little more than 37.1 cents. The silver is very pure. The button is convex with the representation of a deer engraved on it and a hound in pursuit. The eye of the button appears to be as well soldered as though it had been effected by some of our modern silversmiths.

It was in the spring of 1819 when the first discovery of this button was made. On the opposite side of the river is an entrenchment, including a number of mounds. Mr. Oliver Williams lives within three miles of this place and says that during the year 1819 one dozen of the like buttons were ploughed up; and that for every year since, more or fewer of them have been found; the whole amounting to about three dozen. Upon all of them the device is that above stated. These buttons have been found promiscuously, at the depth to which the plough generally penetrates into the earth, or from 9 to 12 inches. The field in which the buttons were found contains from 60 to 70 acres of land. Trees lately grew upon it, before the land was cleared, from 4 to 5 feet in diameter. The country around is rather hilly than otherwise.

An Ancient Furnace Is Discovered

As to other metals found in Tennessee, there is this fact: In the month of June, in the year 1794, in the county of Davidson, on Manscoe’s creek, at Manscoe’s Lick, on the creek, which runs through the lick, a hole or well was dug by Mr. Cafftey, who, at the distance of 5 or 6 feet through black mud and loose rocks found the end of a bar of iron, which had been cut off by a cleaving iron, and had also been split lengthwise. A small distance from that, in yellow clay, 18 inches under the surface, was a furnace full of coals and ashes.

Another fact evinces most clearly, the residence of man in West Tennessee in very ancient times, who knew how to forge metals, make axes and other metallic tools and implements, and probably also the art of fusing ore and of making iron or hardened copper, such as have been long used in Chile by the natives. It also fixes such residence to a period long preceding that at which Columbus discovered America.

In the county of Bedford, in West Tennessee, northeast from Shelbyville, and seventeen miles from it, on the waters of the Garrison fork, one of the three forks of Duck river, on McBride’s branch, in the year 1812, was cut down a poplar tree five feet some inches in diameter. It was felled by Samuel Pearse, Andrew Jones, and David Dobbs, who found within two or three inches of the heart, in the curve made by the ax cut into the tree, the old chop of an ax, which of course must have been made when the tree was a sapling not more than three inches in diameter.

Of 400 years of age when cut down, it must have been 70 when Columbus discovered America, and 118 when De Soto marched through Alabama. If the chop was made by an ax, which the natives obtained from him, it must have been made since the commencement of 282 years from this time; and a poplar sapling of three inches in diameter could not be more than 8 or 10 years of age; making the whole age of the tree, to the time it was cut down, about 300 years in which time a tree of that size could not probably have grown.

Brass Coin with Minerva on It

Two pieces of brass coin were found in the first part of the year 1823, two miles and a half from Murfreesborough, in an easterly direction from thence. Each of them had a hole near the edge. Their size was about that of a nine-penny silver piece of the present time. The rim projected beyond the circle, as if it had been intended to clip it.

On the obverse, was the figure in relief of a female, full faced, steady countenance, rather stern than otherwise; with a cap or helmet on the head, upon the top of which was a crescent extending from the forehead backwards. In the legend was the word Minerva; on the reverse was a slim female figure, with a ribbon in her left hand, which was tied to the neck of a slim, neatly formed dog that goes before her, and in the other a bow.

Amongst the letters of the legend in the reverse, are SL. After the ground, which covered this coin, had been for some years cleared and ploughed, it was enclosed in a garden on the summit of a small hill; and in digging there, these pieces were found eighteen inches under the surface.

A Brief History of Ancient Coinage

There are no Assyrian or Babylonian coins; nor is there any Phoenician one till 400 before Christ. Sidon and Tyre used weights. Coinage was unknown in Egypt in early times. The Lydian coins are the oldest. The Persian coins began 570 before Christ. The darics were issued by Darius Hystaspes 518 or 521 before Christ. Roman coins have been found in the Orkneys, and in the remotest parts of Europe. Romans have three heads upon the side, as that of Valerian and his two sons, Gallienus and Valerian.

On the Roman coins are figures of deities and personifications, which are commonly attended with their names; Minerva, for instance, with her helmet and name inscribed in the legend, sometimes a spear in her right hand, and shield, with Medusa’s head, in the other, and an owl standing by her, and sometimes a cock and sometimes the olive. Diana is manifest by her crescent, by her bow and quiver on one side, and often by her hounds. The Roman brass coins have SC. for senatus consultam, till the time of Gallienus, about the year of our Lord 260. The small brass coins ceased to be issued for a time in the reign of Pertinax, 19 CE, and from thence to the time of Valerian. Small brass coins continued from the latter period till 640 CE. Some coins are found with holes pierced through them, and sometimes with small brass strings fastened.

Earliest Roman Coins Date Back to Antoninus

Such were worn as ornaments of the head, neck, and wrist, either by the ancients themselves, as bearing images of favorite deities, or in modern times when the Greek girls thus decorated themselves. From these criteria it may be determined, that these metals are not counters but coins. Of all the Roman coins that have been found in Tennessee and Kentucky, the earliest bears date in the time of Antoninus, the next in the time of Commodus, the next before the elevation of Pertinax, and the last in the time of Valerian. Coins prior or subsequent to the space embraced in these periods are not found; and from hence the conclusion seems to be furnished, that they were brought into America within one or two centuries at furthest, after the latter period, which is about the year of our Lord 354, and thence to 260; and by a people who had not afterwards any intercourse with the countries in which the Roman coins circulated.

One of these pieces was stained all over with a dark color resembling that of pale ink, which possibly is the verugo peculiar to that metal, which issued from it after lying in a dormant state for a great length of time, and which thus preserved it from decay. The legend on the reverse, on the lower part, below a line across are the letters “EL. SL. RECHP.—ENN.”

The author, since writing the above, has seen another coin of the same metal precisely, which seems to be a mixture of silver and brass. Upon it, on one side, is the figure of a man’s face; and in the legend, LEOPOL. DG. IMP. On the other, under a mark or cross: EI. SL.; also, the sun at the top; and in the legend, only a contraction of those in the larger piece, namely, RL. C. PERNN.

This, then, is a German coin of modern date.

ROMAN COINS FOUND AT THE OHIO FALLS

In 1997, the Ohio Museum took possession of a cache of Roman coins that was originally discovered in 1963 by a construction engineer excavating on the north shore of the Ohio River during construction of the Sherman Minton Bridge. Coin experts have examined these Roman coins and declared them to be authentic.

Fig. 9.8. Claudius II (left), Maximinus II (right) (courtesy of Troy McCormick)

The discoverer kept most of the hoard for himself but gave two of the coins to another engineer on the project. In 1997 the second engineer’s widow brought these two to Troy McCormick, then manager of the new Falls of the Ohio State Park Interpretive Center in Clarksville, Indiana, not far from the find site. She donated them to the museum, where they remain today.

The larger coin has been identified by both Mark Lehman, president of Ancient Coins for Exploration, and Rev. Stephen A. Knapp, senior pastor at St. John Lutheran Church, Forest Park, Illinois, and a specialist in late Roman bronze coinage, as a follis of Maximinus II from 312 or 313 CE, despite McCormick’s original identification of the coin as a 235 CE bronze of Maximinus I.

The coin of Claudius II is similar in type and period to the recently discovered Roman coins from Breathitt County, Kentucky, but is in a much better state of preservation. The latter coin makes this find several decades later than the Severian Period (193 to 235 CE), to which the Roman head from Calixtlahuaca, Mexico, has been attributed on stylistic grounds. Unfortunately, the discoverer moved south to work on another bridge shortly after the find, and the second engineer’s widow could not remember his name, so the bulk of the hoard is lost.

For several years, the Falls of the Ohio State Park Interpretive Center had an exhibit about the find that displayed several casts of both sides of the two originals, so as to reflect the approximate number of coins originally in the hoard. The two original coins, depicted in fig. 9.8 (see above) are in storage and were not on public display. In February 2012, I was informed that the replicas were still on display, despite an earlier report to the contrary, in the Interpretive Center as part of the Myths and Legends exhibit, and that they will remain there at least into 2014.

Recently, three more heavily weathered Roman coins found in Breathitt County were examined hands-on by Norman Totten, professor of history, now professor emeritus, at Bentley College. Totten identified the two thinner coins as antoniniani, a type of bronze Roman coin minted between 238 and 305 CE. The obverses depict an unidentifiable emperor wearing the distinctive “solar crown” of the period. The reverse of one coin depicts two figures standing facing what apparently is a central altar, while that of the second coin depicts a female standing figure facing left with a cornucopia in her right hand.

These would originally have had a silver surface, which is long since gone. The third coin is thicker and depicts a bust facing right and wearing a laureate wreath rather than a crown. The reverse, according to Totten, is perhaps a figure of a centaur walking to the right and looking back. Its flan (the metal disk from which the coin is made) seems to be of a North African (Egyptian) or Middle Eastern type. This coin probably dates to a similar period to that of the two antoniniani (the singular of which is antoninianus).