APPENDIX B

Laryngeals Again?

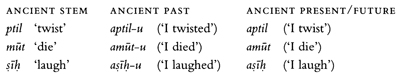

In Chapter 6 I suggested that the a-mutation may have been the first step taken by the prehistoric forebear of the Semitic languages towards the root-and-template system. The a-mutation was the change of vowels in the ancient stem from u or i to a, giving rise to pairs such as aktum-aktam ‘I covered-I will cover’, aptil-aptal ‘I twisted-I will twist’, amūt-amāt ‘I died-I will die’. I argued that this mutation must have emerged on similar lines to the cycle of effort-saving changes and analogy that brought about the i-mutation pattern in German nouns such as gast-gest![]() and hals-hels

and hals-hels![]() ’. In Germanic, the original culprit for the effort-saving changes was an ending -iz, which coloured the previous vowel from a to e.

’. In Germanic, the original culprit for the effort-saving changes was an ending -iz, which coloured the previous vowel from a to e.

The origin of the Semitic a-mutation lies so far back that it is impossible to know what precise phonetic environment was responsible for bringing it about. Still, even if only out of sheer curiosity, it is tempting to speculate what the culprits for the a-mutation in Semitic might have looked like. One educated guess would be that the culprit in question may not have been a vowel at all, but rather a group of consonants: the ‘laryngeals’ which have already featured in Chapter 3, in connection with Saussure’s theory about the vowel system of Proto-Indo-European. Saussure postulated that the prehistoric ancestor of the Indo-European languages had some long-lost sounds which had coloured the vowels in their vicinity, but which then disappeared from all the daughter languages. After his death his theory was proved, when one of these rogue sounds was found in the newly discovered but very ancient Indo-European language Hittite.

Now, in the Semitic languages, one does not need visionary powers to hypothesize the existence of laryngeals, for they are very much around even today. What is more, there is even historical evidence to show that these laryngeal consonants forced vowels in their vicinity to change to a. The reason for this colouring is that the laryngeals are produced so far down the throat that in order to utter them, the tongue has to take a position very similar to an a anyway. In Hebrew, for example, the word for ‘apple’ was originally tapū![]() , but the laryngeal sound

, but the laryngeal sound ![]() caused the word to change to tapūa

caused the word to change to tapūa![]() . A helping-vowel a was inserted before the

. A helping-vowel a was inserted before the ![]() , in order to enable the mouth to move more easily into the shape needed for it. Crucially, however, this change only happened when the laryngeal was at the end of a word. When there was another vowel following

, in order to enable the mouth to move more easily into the shape needed for it. Crucially, however, this change only happened when the laryngeal was at the end of a word. When there was another vowel following ![]() , there seems to have been no time for this leisurely helping-vowel a to creep in, so the plural ‘apples’ remained tapū

, there seems to have been no time for this leisurely helping-vowel a to creep in, so the plural ‘apples’ remained tapū![]() -im, and was not modified to tapūa

-im, and was not modified to tapūa![]() -im.

-im.

It is quite possible that the culprits behind the prehistoric a-mutation were also laryngeal consonants. We can never hope to reconstruct the actual set-up in which they caused the vowel to change, but here is one way it could have happened. Suppose that once upon a time, the past tense was not bare-ended, as I presented it in Chapter 6, but was marked by an ending. It doesn’t really matter what the ending was, so let’s say for the sake of argument that it was -u. Let’s also suppose that the future tense (which may have started out in life as just a more indefinite present tense) was a form without any ending at all:

Now imagine for a moment that an effort-saving change was set in motion, similar to the one which modified the Hebrew ‘apple’: speakers inserted a helping-vowel a before the laryngeal ![]() , but only when it was at the end of the word. How would such a change affect the forms above? The present tense a

, but only when it was at the end of the word. How would such a change affect the forms above? The present tense a![]() ī

ī![]() would become asīa

would become asīa![]() , because the

, because the ![]() is at the end of the word. But in the past tense a

is at the end of the word. But in the past tense a![]() ī

ī![]() -u, where the

-u, where the ![]() was not at the end, no change would have occurred. In other words, the ending -u could have ‘protected’ the past tense from the change. After the change has taken its course, the situation would look like this:

was not at the end, no change would have occurred. In other words, the ending -u could have ‘protected’ the past tense from the change. After the change has taken its course, the situation would look like this:

![]()

Now suppose that some generations later, the ending -u of the past tense is eroded away and eventually disappears altogether. So forms like a-![]() ī

ī![]() -u end up as just a-

-u end up as just a-![]() ī

ī![]() . The only distinguishing feature now left between the past and the present/future tense would be the gliding-vowel a inside the stem:

. The only distinguishing feature now left between the past and the present/future tense would be the gliding-vowel a inside the stem:

![]()

Speakers in subsequent generations would have no idea that the a in a-![]() īa

īa![]() was originally inserted purely as an effort-saving device. They would simply observe a pattern, whereby the only differentiating feature between past and present tenses is the gliding-vowel a inside the stem. So their order-craving mind could interpret this helping-vowel a as a meaningful pattern, and assume that the reason why it was there was to indicate the present/future. And once this pattern is recognized, it could be extended by analogy to other verbs like mūt, ptil, and so on, which never had a laryngeal to their name in the first place:

was originally inserted purely as an effort-saving device. They would simply observe a pattern, whereby the only differentiating feature between past and present tenses is the gliding-vowel a inside the stem. So their order-craving mind could interpret this helping-vowel a as a meaningful pattern, and assume that the reason why it was there was to indicate the present/future. And once this pattern is recognized, it could be extended by analogy to other verbs like mūt, ptil, and so on, which never had a laryngeal to their name in the first place:

![]()

As it happens, the forms above are very similar to the forms of the hollow verbs found in the earliest stages of Akkadian. But later on in the history of the language, the vowel sequences ia and ua were ground down and reduced to just a, producing the a-mutation in its pure form: a change from i or u in the past to a in the future:

![]()

Of course, as I stressed above, the scenario presented here is no more than an educated guess, whose only purpose is to illustrate one way in which the a-mutation could have emerged. My only claim is that the development could in general have proceeded along such lines.