APPENDIX C

The Devil in the Detail

Between the three simple vowel templates derived in Chapter 6 and the full complexity of the mature Semitic verbal system lies a mind-boggling amount of detail, much of which can never be recovered. Nevertheless, there are enough clues to give us an idea about how at least some of the more elaborate templates could have evolved, and the following pages will briefly survey the possible origins of the ‘reflexive’, ‘intensive’, ‘causative’ and ‘passive’ templates. Finally, the last section will look at the origin of a rather fancy template in modern Hebrew, in order to give some idea of the sort of processes that could have made the root-and-template system burgeon in complexity.

1. Reflexive

The reflexive nuance ‘snog oneself’ is expressed in the Semitic languages by templates that insert a t between the first two root-consonants. In Arabic, for instance, ![]() is the template for ‘snog yourself!’ The obvious question about this reflexive t is where it could have sprung from, and how it managed to find its way in between the consonants of the root. As with most other details, the ultimate origin of the t lies well beyond historical reach, but the most likely explanation is that t started out as a full ‘reflexive pronoun’, an independent word like ‘himself’. This pronoun (perhaps originally ta) would have appeared before the verb, so that something like ‘ta snog’ would simply have meant ‘snog himself’. Then, through the familiar processes of erosion, ta could have fused with the verb to become a prefix:… t(a)-snog.

is the template for ‘snog yourself!’ The obvious question about this reflexive t is where it could have sprung from, and how it managed to find its way in between the consonants of the root. As with most other details, the ultimate origin of the t lies well beyond historical reach, but the most likely explanation is that t started out as a full ‘reflexive pronoun’, an independent word like ‘himself’. This pronoun (perhaps originally ta) would have appeared before the verb, so that something like ‘ta snog’ would simply have meant ‘snog himself’. Then, through the familiar processes of erosion, ta could have fused with the verb to become a prefix:… t(a)-snog.

But what could have pushed this prefix in between the root consonants? The culprit must have been a fairly common type of effort-saving change, called metathesis, in which a pair of consonants swap places, to make uttering them in sequence easier. Examples of metathesis can be seen with the Old English verb aksian, in which the pair ks was jiggled around to give the modern English as ‘ask’. Similarly, Old English hros became ‘horse’, brid changed to ‘bird’, thrid to ‘third’, and waps to ‘wasp’.

There are very good reasons to suspect that a metathesis must have been responsible for making the reflexive t swap places with the first root consonant ![]() In fact, in some of the Semitic languages, such as Hebrew, the metathesis did not occur in all verbs, but only when the first root-consonant was difficult to pronounce immediately after a t. So it is likely that the other Semitic languages also started out with a more haphazard metathesis, but that at some later stage, the metathesis was extended by analogy, and regularized to all verbs.

In fact, in some of the Semitic languages, such as Hebrew, the metathesis did not occur in all verbs, but only when the first root-consonant was difficult to pronounce immediately after a t. So it is likely that the other Semitic languages also started out with a more haphazard metathesis, but that at some later stage, the metathesis was extended by analogy, and regularized to all verbs.

2. Intensive

The intensive templates in Semitic are characterized by the doubling of the second root consonant. In Akkadian, for instance, the intensive future template is ![]() (‘I will snog intensely’), and in Hebrew, the past intensive is

(‘I will snog intensely’), and in Hebrew, the past intensive is ![]() (‘he snogged intensely’). It is possible that this consonant doubling is a remnant of what started out as the reduplication (repetition) of the whole stem. Reduplication is in fact an extremely common strategy among the world’s languages. Forms such as runrun, cutcut, or redred are used in many languages to express meanings such as ‘run a lot’, ‘cut repeatedly’, ‘very red’. But often, erosion hacks away at the repeated forms, so that only ‘partial reduplication’ remains. The Latin word memento, for instance, is a relic of a reduplication of the Proto-Indo-European root *men ‘think’, presumably through an erosion of menmen to memen. Sometimes, erosion or assimilation of reduplicated forms can create doubled middle consonants. In the Micronesian (Malayo-Polynesian) language Trukese, for instance, the adjective cön ‘black’ has an intensive form cöccön, which clearly comes from an original duplication cöncön (cöncön → cöncön). In this way, a doubled middle consonant may come to be associated in speakers’ minds with an intensive meaning, and the pattern may thus be extended and regularized. In Semitic, duplication also seems to have reached verbs from intensive adjectives, but the details of the process are beyond our reach.

(‘he snogged intensely’). It is possible that this consonant doubling is a remnant of what started out as the reduplication (repetition) of the whole stem. Reduplication is in fact an extremely common strategy among the world’s languages. Forms such as runrun, cutcut, or redred are used in many languages to express meanings such as ‘run a lot’, ‘cut repeatedly’, ‘very red’. But often, erosion hacks away at the repeated forms, so that only ‘partial reduplication’ remains. The Latin word memento, for instance, is a relic of a reduplication of the Proto-Indo-European root *men ‘think’, presumably through an erosion of menmen to memen. Sometimes, erosion or assimilation of reduplicated forms can create doubled middle consonants. In the Micronesian (Malayo-Polynesian) language Trukese, for instance, the adjective cön ‘black’ has an intensive form cöccön, which clearly comes from an original duplication cöncön (cöncön → cöncön). In this way, a doubled middle consonant may come to be associated in speakers’ minds with an intensive meaning, and the pattern may thus be extended and regularized. In Semitic, duplication also seems to have reached verbs from intensive adjectives, but the details of the process are beyond our reach.

3. Causative templates

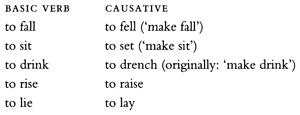

The causative templates are characterized by a prefix ša- (or a weakened form ha- or even just a-), as in Akkadian ![]() ‘he caused to snog’. The simplest explanation for the origin of the prefix ša would be that it started out in life as an independent word, a verb meaning ‘make’, ‘cause’, or ‘do’. According to this theory, something like ‘ša snog’ would literally have meant ‘make snog’, and then, through erosion, the ša must have fused with the verb to become a prefix. This scenario would certainly accord with evidence from other languages, where verbs like ‘cause’ or ‘do’ are often the source of causative constructions. In the Germanic languages, for instance, something that comes close to a causative template has arisen from a verb meaning ‘make’, through the familiar i-mutation. In English, there are a few verbs (and adjectives) that change their vowel to mark a causative:

‘he caused to snog’. The simplest explanation for the origin of the prefix ša would be that it started out in life as an independent word, a verb meaning ‘make’, ‘cause’, or ‘do’. According to this theory, something like ‘ša snog’ would literally have meant ‘make snog’, and then, through erosion, the ša must have fused with the verb to become a prefix. This scenario would certainly accord with evidence from other languages, where verbs like ‘cause’ or ‘do’ are often the source of causative constructions. In the Germanic languages, for instance, something that comes close to a causative template has arisen from a verb meaning ‘make’, through the familiar i-mutation. In English, there are a few verbs (and adjectives) that change their vowel to mark a causative:

The pattern began, millennia ago, with the Proto-Indo-European verb *yo ‘make’. By the time of Proto-Germanic, a form of this verb, *-ian, must have fused with the preceding verb to give a causative ending. So a Proto-Germanic verb like *fall-ian was just the combination ‘fall-make’. Then, the i of the ending -ian caused an i-mutation in the preceding vowel, and so the a of fall changed to e, to give *fell-ian. Later on, the ending was entirely eroded, and so *fell-ian ended up as ‘(to) fell’.

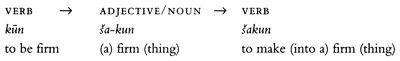

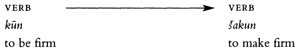

It would appear, then, that the most tempting origin for ša- in Semitic is simply a verb meaning ‘make’ or ‘cause’. But there are various reasons to believe that the actual development in Semitic was less straightforward. Earlier on, I mentioned that the prefix ša- served to derive nouns or adjectives from verbs (and was thus involved in the cycles of swelling of new verbs from old ones). And it may be that the origin of the causative prefix ša- should also be sought in such cycles of swelling from verb to noun to verb. When a verb is derived from a noun or adjective, one of the most common resulting meanings is ‘to make (into) X’, as, for example, in English ‘to ice’, ‘to compact’, to ‘cool (something)’, and so on. Now consider a cycle like this:

The second stage of this process creates the causative meaning ‘make into an X’ as a natural result of the transformation of a noun/adjective into a verb (just as in ‘to ice’). But if we now ignore the middle stage, and only look at the two verbs on either side, the following relation has emerged:

From the historical perspective, the link between ‘be firm’ and ‘make firm’ is not direct, but goes through an adjective or noun. But new speakers who spot the relation between the two verbs may no longer be aware of the original link between them, and simply (mis)interpret ša- as a prefix that turns a verb ‘to X’ into another verb ‘to make X’ (or ‘to cause to X’). And once they recognize the pattern, they can extend it by analogy and generalize it to other verbs, thus making it into a regular causative prefix. It seems likely that a process of this nature was responsible for creating the causative prefix ša-.

4. Passive template

The passive template (‘to be snogged’) is characterized by the doubling of the first root consonant, as in Akkadian ![]() (‘I was snogged’). What lies behind this doubling is the (‘Santa Siesta’) principle of assimilation. Originally, the passive was formed with a prefix n:

(‘I was snogged’). What lies behind this doubling is the (‘Santa Siesta’) principle of assimilation. Originally, the passive was formed with a prefix n: ![]() and in fact, in Arabic the n is still mostly audible. But in the other Semitic languages, the n assimilated to the first consonant of the root, so that

and in fact, in Arabic the n is still mostly audible. But in the other Semitic languages, the n assimilated to the first consonant of the root, so that ![]() became

became ![]()

But what could have been the origin of passive prefix n-? In light of the latest research, it seems probable that the n-prefix in Semitic started out as an independent verb (perhaps na), meaning ‘be’ or ‘become’. This verb would have been placed before the verbal adjective ![]() ‘(a) snogged (thing)’ to produce verbal constructions with a passive meaning:

‘(a) snogged (thing)’ to produce verbal constructions with a passive meaning: ![]() ‘I was/became snogged’. Later, the verb na must have eroded and fused with the adjective, so that

‘I was/became snogged’. Later, the verb na must have eroded and fused with the adjective, so that ![]() merged into

merged into ![]() ‘I became snogged’ (and later

‘I became snogged’ (and later ![]() ).

).

5. Passive of reflexive, or how one is ‘made to snog oneself’

Various other templates could have developed along similar lines to the four examples mentioned so far. But it would be misleading to imagine that each of the many dozens of the templates in Semitic emerged in isolation, and without any input from the rest of the system. In fact, as I mentioned in the end of Chapter 6, when the system grows in complexity, there is also a growing scope for speakers to recognize regular patterns and correspondences between existing templates, and to produce innovations by analogy on a higher level. To see what such higher-level analogical innovations can involve, we can leave prehistory behind and jump all the way to the 1940s, to see how an entirely new template was created in modern Hebrew, ![]() ‘he was made to snog himself’.

‘he was made to snog himself’.

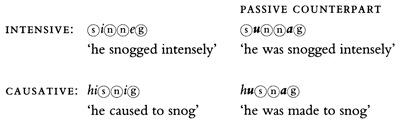

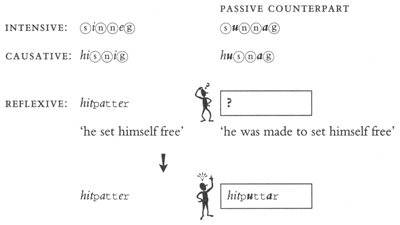

Hebrew has an intensive and a causative template, each of which also has a passive counterpart:

In both cases, the passive counterpart is formed by taking the two vowels of the original template (i–e or i–i) and changing them into the sequence u–a. So in speakers’ perception, the vowel sequence u–a has come to be associated with a passive meaning.

Hebrew also has a reflexive template, ![]() ‘he snogged himself’. Until the 1940s the reflexive template didn’t have any passive counterpart – after all, it is rather unusual that one would have cause to speak about someone who was ‘made to do something to himself’. But in modern political life, all kinds of unlikely things can happen. Take the root p-t-r (‘set free’), for instance, which in the reflexive template yields hitpatter ‘he set himself free’, or more specifically, ‘he resigned’. It is not unheard of in politics that people are ‘made to set themselves free’, so to speak. And in 1948, a politician vented his frustration at having been forced to resign by coining a new form. Recognizing the u-a sequence as the mark of the passive counterpart from the intensive and causative templates, he extended this sequence by analogy to the reflexive form:

‘he snogged himself’. Until the 1940s the reflexive template didn’t have any passive counterpart – after all, it is rather unusual that one would have cause to speak about someone who was ‘made to do something to himself’. But in modern political life, all kinds of unlikely things can happen. Take the root p-t-r (‘set free’), for instance, which in the reflexive template yields hitpatter ‘he set himself free’, or more specifically, ‘he resigned’. It is not unheard of in politics that people are ‘made to set themselves free’, so to speak. And in 1948, a politician vented his frustration at having been forced to resign by coining a new form. Recognizing the u-a sequence as the mark of the passive counterpart from the intensive and causative templates, he extended this sequence by analogy to the reflexive form:

And thus the form hitputtar was born, meaning ‘he was made to set himself free’, that is, ‘he was forced to resign’. This form soon caught on, and was then extended to other verbs as well, such as ‘he was made to volunteer’ or ‘he was made to wash himself’. And so a new template emerged: ![]() with the nuance ‘he was made to snog himself’.

with the nuance ‘he was made to snog himself’.

Of course, in itself, this example may seem rather insignificant. Nevertheless, it does demonstrate the principle by which many of the dozens of templates in Semitic could have emerged. As the system grew more complex, more and more higher-level analogies could be formed. For instance, when a template with a new nuance emerges, say the ‘iterative’ (‘he kept on snogging’), this new nuance can interact with existing distinctions, and so by high-level analogies, new templates can be formed for things like ‘causative iterative’ (‘he kept causing to snog’), ‘passive iterative’ (‘he kept being snogged’), and so on. So once a critical mass of templates (perhaps only ten or so) had emerged, there could have been an ‘explosion’ in the number of new templates formed, leading to the dozens attested in the historical languages.