CHAPTER 10

The Route to Simplicity: Index Funds Balance Costs and Boost Returns

Investment management is a field fraught with fragility and fallibility, a field in which today’s careful, rational fund selections are too often tomorrow’s embarrassments.

—John Bogle

The idea that you can outperform a market average more than once is like thinking you’re going to find a talking flounder. If it does happen—and you get cocky—you will eventually sink back to below-average status. For most investors, the intangible truth is that everyone would like to beat the market, but few ever do, and not because of personality or intellect. As a group, investors represent the entire market, according to modern portfolio theory; therefore it’s not possible to beat the market over long stretches of time.

You can get lucky and go against the grain. Pick an out-of-favor sector that rebounds. That takes guts and a bit of pluck, and most people don’t like to take those kinds of risks unless they are being paid by someone else to run money. There are so many ways of getting it wrong that even the smartest of investors fail miserably at market timing the way most golfers fail to get close to a hole in one.

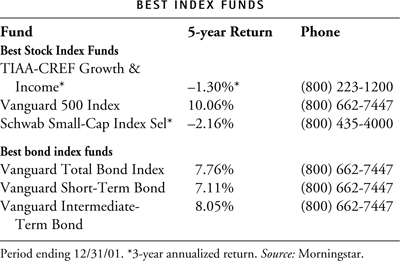

Carlton Martin is paid to either stay near or beat the market average. As the manager of the $700 million TIAA-CREF Growth & Income Fund, he’s trying to get a slightly above-average return through what is called an “enhanced index/active approach.” This style of “dual investment management strategy” places the bulk of the fund’s assets in the S&P 500 Index. Martin is doing what most of us need to be doing with our portfolios and what most of us want to be doing. By aiming for the average return of the S&P 500—and then “enhancing” that return by actively managing a portion of the portfolio—Martin is trying to put a little spin on the ball to reap better returns. The avid jogger and golfer has fulfilled that part of his charter, averaging 20.5 percent annual return over the past three years, compared to 17.63 percent for the competing Vanguard S&P 500 Fund. Since inception, the fund returned an average 8.31 percent (from September 2, 1997, to December 31, 2000).

With an undergraduate degree in accounting and banking experience, neither field appealed to the Jamaican-born Martin, who obtained his MBA from American University in 1972, at the beginning of a miserable period for stock investors. He thought about becoming a credit officer for the World Bank, but took a job with TIAA-CREF in 1980 and discovered that the intellectual challenge of analyzing stocks was engaging and addictive.

Martin has the flexibility to go stock picking when he sees opportunities. The passive portion of his portfolio is about 50 percent to 60 percent of total assets, leaving him 40 percent to 50 percent to invest as he sees fit. Typical index funds have 100 percent of their portfolios as fixed investments in the stocks representing an index. The popular S&P 500 Index, for example, has stocks representing five hundred of the largest companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange. The Wilshire 5000, also referred to as “the total market,” represents most of the stocks listed on all of the major exchanges, so it’s the broadest possible market index. There are also indexes representing small-cap, mid-cap, value, and international funds, plus bonds and REITs.

The main virtue of an index fund is that it’s destined to beat most actively managed mutual funds over time because the costs of operation are lower than actively managed funds. The holdings of index funds are almost never sold (unless a stock or two drops out of the index), so there are virtually no management and transactions costs. Because there’s no turnover—the buying and selling of securities—the fund managers don’t have to pay commissions (and charge shareholders), lowering a fund’s expense ratio. This percentage is the annual amount of money a fund manager deducts from assets every year to cover the costs of running the fund. An annual expense ratio of 1.5 percent a year is outrageous in the world of index funds, where the big index funds can be run for as little as 0.20 percent a year. Whatever you pay a fund manager out of your own money reduces your total return, so the lower the expense ratio, the better. (Martin’s fund weighs in at 0.43 percent, mostly due to a waiver of 0.50 percent of management fees until 2006.)

Although his fund suffered with the rest of the pack in 2000 (down 7.3 percent), Martin posted good numbers in 1998 and 1999, beating the S&P 500 in each of those years. Despite TIAA-CREF’s mission to manage $270 billion for 2 million employees at eleven thousand colleges and related institutions, Martin has a fair amount of latitude to work with his portfolio and the twenty-four analysts who support it.

“We are completely opportunity driven,” Martin says of the active part of his portfolio. “We have a combination of growth and value and we tilt toward large-cap growth and large-cap value. In picking out stocks, we try to find pricing anomalies [where the stock price doesn’t reflect the company’s value]. We have found that more than 40 percent of the companies out there are mispriced.”

Martin’s blended approach allows him to look at larger demographic trends and companies that are well-managed but bargain-priced. He won’t let a single company comprise more than 5 percent of his portfolio, which is a common risk-reduction technique. He also keeps an eye on specific sectors like technology and health care to make sure that he’s weighing their risk to reward ratios appropriately. That helps buttress the portfolio against sector rotation, although he got stung in 2001 by some of his technology holdings.

Another risk management technique is the portfolio’s requirement that it hold at least 80 percent in dividend-producing stocks. The dividend yield of the portfolio is slightly below that of the S&P 500 Index (0.8 percent as this goes to press), but it’s more than what one would find in an all-technology sector fund. Along the way, he may pick up some battered, well-managed technology companies and add to his pharmaceutical company holdings. He sees a rebound in technology and is confident that aging baby boomers will support the growth of pharmas for years to come. All told, the fund’s turnover is some 20 percent to 30 percent a year with the average holding period of his stocks from three to five years.

“When I talk with my analysts, we discuss the market landscape and the beneficiaries within that landscape. Who will benefit and add value? We don’t want to trade in and out of stocks. We need a long-term thesis and perspective. We look at an 18-month time frame initially and look for leaders [in specific industries] at attractive valuations [prices].”

Investing in companies that “benefit and improve the quality of life,” Carlton’s fund has a socially responsible perspective as part of one of the largest pension systems in the world. He also has the luxury of keeping long-term investors, who typically don’t withdraw their money when the market turns ugly. TIAA-CREF investors also make biweekly contributions, so he has a steady flow of cash to invest. Like the value managers, he’s always interested in “companies that have an ability to generate cash flow in the future.” Following the average of S&P 500 stocks, he tries to match the p/e’s and earnings growth of the broad index while scouting around the world for stocks that might beat it.

It’s difficult to say whether Martin’s “dual management investment strategy” will succeed over time. The odds are that he will somewhat keep pace with the S&P 500, although never consistently beating it over any ten-year period. The combination of dividend-paying growth stocks, some value picks, small companies, and foreign securities (up to 20 percent) is a sensible combination to allay volatility concerns. This is certainly not the most conservative approach, nor is it daring like a sector fund. It will have the volatility of the broad market while keeping in mind Martin’s suggestion that those committed to the stock market “be able to sleep at night knowing there will be some volatility.”

Martin’s synthesis of a standard index approach—and the low operating costs—with some active stock picking is a workable model for most investors with an eye on risk. It won’t sacrifice too much return, however, as it has some reasonable safeguards built in for long-term investors.

Why Costs Matter: John Bogle’s Bagel

Carlton Martin gives us a point of departure to meet John Bogle, who has been at the epicenter of index-fund investing for the past quarter century. When you see the gaunt, distinguished Bogle speak, you realize that he’s more than the godfather of index funds. He’s a truth teller who often berates the mutual-fund and money-management industries. Having received a heart transplant a few years ago, he is as vigorous as ever, and continues to staunchly defend the idea that investing generally costs the investor too much. The former chairman of the $570 billion Vanguard Group, the second-largest mutual fund manager on the planet (behind $896 billion Fidelity Investments), Bogle has been in the business for fifty years and can document how his business evolved in stunning detail.

Despite his position as a leader in an industry that makes nearly a penny and a half on every dollar put in a stock mutual fund, Bogle’s resonant baritone voice is revered by the individual investors who mob him after every speech. He clearly tries to represent the little guy against a $6.8 trillion industry. Of the several times I’ve heard Bogle address the Morningstar mutual funds conference (I’ve attended every conference from its inception through 2001), the rooms in which he speaks are as quiet as funeral homes. Not every money manager in the room wants to hear his message, although everyone from a hotshot sector manager to the guy refilling the water carafe is listening raptly.

Playing on a William Safire metaphor, Bogle once called the index fund a “bagel.” It’s hard and crusty, not always the first choice for breakfast. More often than not, however, Bogle says the industry serves up “doughnuts,” managed funds of all stripes that attempt to beat the index. Most doughnuts are sweet confections and offer empty calories in the Bogle lexicon. They fail to match the power and durability of the proverbial bagel. The failure of doughnutlike funds is predicated on the returns of the indexes, which beat nearly every money manager over time.

On the one hand, the indexes represent benchmarks of a cornucopia of securities. In an index, you have diversification, a little yield, and the average of all the securities in one class. In one number, you have the market average for the kind of securities you want to depict. Large-company growth stocks are represented by the S&P 500; small-company stocks by the Russell 2000; foreign stocks by the MSCI EAFE Index. Any money manager who manages securities can be compared to the indexes. If they beat the index, they’re above average, but these managers are few and far between. If they’re underperforming, they’re in the majority. Most managers can’t beat the index consistently. Comparing managers to indexes is a universal standard in the business today.

The indexes also allow you to compare how your manager did by specific asset class. For example, say you have a mid-cap stock fund. There’s an S&P Midcap Index to use as a benchmark. How about long-term government bonds, European stocks, or even mortgage securities? There are indexes for all of those assets. There’s a clear measure of objectivity with indexes because the companies maintaining the indexes don’t have anything to do with the majority of mutual funds or money managers. Standard & Poor’s, for example, is owned by McGraw-Hill, which publishes Business Week, Moody’s Investors Guides, and thousands of business books. The question with any mutual fund, partly thanks to Bogle, is, “Did my fund beat the index?” Most don’t.

Since indexes began to be used to judge the performances of money managers, the business has not been the same. When a money manager brags that “I’m returning twelve percent a year,” it means little until you compare it to an index that measures the kinds of stocks he’s managing. If the S&P 500 is returning 17 percent a year, he has an empty boast. He’s underperforming the market index. You’d be better off in an S&P 500 index fund charging you 0.20 percent a year rather than pay this guy 2 percent a year to produce below-average returns. You can make more money and add simplicity to your portfolio with one move.

When John Bogle launched the S&P 500 fund for Vanguard more than twenty-five years ago, the investment community was amused. How dare this guy compare us to some obscure index, they chortled. The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) was the master barometer of the times, even though it only tracked the performance of thirty large industrial stocks, leaving whole industries unrepresented. As old habits die hard, even today most news organizations routinely and mistakenly quote the hourly DJIA as if it were the sole proxy of what a market of more than five thousand stocks is doing. It’s simply ridiculous to make such an assumption when there are so many different components of the market that can be averaged into a more holistic picture by the S&P 500, which represents a much larger cross-section of corporate America—75 percent of stocks by capitalization—or the Wilshire 5000, which gives you the big picture.

Vanguard’s index funds grew over the years as Bogle kept expanding his offerings to track all kinds of stocks and bonds. The rest of the industry watched and waited until they saw Vanguard raking in some real money in the 1990s—Vanguard reaped $187 million from its fees on the S&P 500 Fund in 2000 alone. Bereft of ways to beat the market index on their own, the major fund and brokerage houses started to copy Bogle, who was able to run Vanguard funds “at cost.” The industry saw that not only were investors learning about the benefits of index investing, they were making money by eschewing active managers who were turning over their portfolios at a rapid clip and charging people for the privilege of underperforming the index. Astute investors wised up and saw their money being wasted for no particular reason other than obeying the ego-space myth that they, too, could beat the market with active management.

Of the more than eight thousand mutual funds on the market, costs declined on average across the board in the 1990s. Whether Bogle spurred this development or the industry simply had better economies of scale and passed along savings to shareholders, industry watchers will be debating for a long time. Bogle certainly gained an Olympian influence over this fifty-year career in the business. He used his public appearances and many writings to herald the virtues of curtailing costs and indexing. The following chart from the Investment Company Institute, the trade organization representing the mutual fund industry, tells some of the story of the reduction in costs.

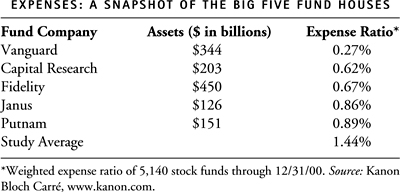

I have a fairly certain feeling that Bogle would find the previous table appalling since he would argue that fund groups haven’t lowered their expenses enough and some of the management fees they charge are still usurious. Bogle, however, is in a good position to say he practiced what he preached. A study done by Kanon Bloch Carré, a New York–based investment research and management firm, found that Vanguard’s weighted expense ratio was the lowest of the top five fund groups and 5,140 funds surveyed. Here’s how the study rated the top five mutual fund houses, which represent 50 percent of all mutual fund assets:

Although these numbers don’t seem very large, consider that the spread between the lowest and highest ratios—all of which are below the overall average of this study—represents a factor of nearly 200 percent. The difference between Fidelity, the largest fund manager, and #2 Vanguard means that Fidelity is charging twice as much as Vanguard to manage stock funds.

HOW INDEXING WORKS

There are two ways an index can track a basket of stocks, bonds, or REITs. The replication method buys stocks or bonds in similar proportions to the index itself. Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that GE represents 1% of the S&P 500. An index fund using the replication method would invest 1% of its assets in GE. Another method is the sampling method, which is often employed for bond funds. Using a computer program, managers identify a representative sample of securities to buy that will mimic the index. That way, the index fund has a representative sample of the securities in the index without having to own every security. Index fund managers often have the freedom to invest in securities outside the index to raise potential returns and lower potential risk.

These figures, of course, are like looking at a herd of beef cattle and trying to guess how much each cow weighs. They are meaningless unless you look at the relationship between costs and returns. In no way can you interpret this study as a blanket endorsement for Vanguard, since it manages so much money in many different channels and each fund performs differently. To understand how costs impact performance, you need to understand the hole that money flows into if you’re an unsuspecting investor.

Why Costs Matter: The Doughnut Hole

You don’t have to agree with Bogle to understand that an excessive fee on any investment is money going into a black hole. By excessive, I mean paying more than average for a mutual fund, brokerage account, or even DRIP account. Costs are critical because a money manager can provide you all the services in the world and it won’t add a cent to your return. It’s the doughnut hole. After you’d loaded up on the sugar and carbohydrates from that sweet little morsel, you have total emptiness. I don’t want to sound nihilistic, so let’s look at the record:

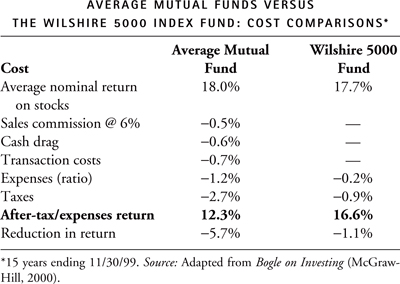

• You have to look at all of the costs in money management. I’ve barely touched upon sales fees, redemption fees (Vanguard charges these), or the fact that some stock-fund managers may create “opportunity risk” by investing in cash and missing market upturns. Bogle calls this a “cash drag.” And then there’s turnover, the costs of buying and selling securities, and other management expenses. Transactions costs (buying/selling securities) are not reflected in the fund expense ratio, so you never really get a complete picture of how much a fund is costing you. “The doughnut-like mutual funds, ever-searching for the market’s sweet spots, turn over their portfolios at an astonishing rate of 90% per year—clearly short-term speculation, not long-term investing,” Bogle writes in his epic Bogle on Investing: The First 50 Years (McGraw-Hill, 2000). Bogle goes on to estimate what turnover costs added to paying taxes on high-turnover funds. He reached this conclusion:

Bogle’s skewed example, which I’ve edited for clarity, is not a representative sample of all stock funds, nor does it fairly compare all “no-load” (no sales charge) funds or all funds with the same expense levels. His larger point is that active management will dramatically eat into your total return before you’ve even looked at comparing performance. That means, using Bogle’s example, you could be getting a 2 percent return if stocks are returning 8 percent in an actively managed fund. Does that sound right?

I know it’s hard to get hot and bothered over not making 4.3 percent. What if the fund manager is a solid performer? What if the manager can get close to the market index? Isn’t it worth it? Suppose the manager has a great year and beats the index. It’s been known to happen.

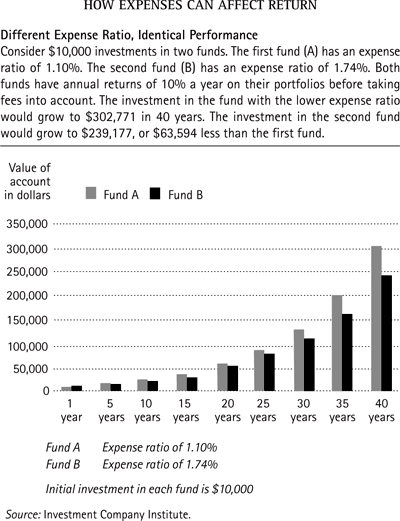

• You have to consider the impact of expenses over time. Bogle is hardly sugar-coating his message when he notes, “The typical equity fund has proven dangerous to the wealth of investors who succumbed to its sugary smiles.” Then he offers up an example that hits home. Say you invested $10,000 in the average mutual fund over the past fifteen years. You would have $57,000 after a decade and a half. Then compare it to investing the same amount in the Wilshire 5000 Index; you’d have a cool $100,000. Put another way, the managed stock fund gave you 48 percent of the market’s return after fees and expenses were deducted from your account over time, while the low-expense index fund gave you 87 percent of the market’s return minus expenses. That’s math you can’t argue against.

• Even the best money managers can’t beat the index. Every year since 1987, Morningstar awards a “manager of the year” honor to the bond and fund managers who managed to not only best their peers’ performance, but beat market averages. Ever a spoilsport, Bogle looked at those managers’ cumulative returns from 1987 to 1998, then compared them to the return of the S&P 500 over the same period—and their follow-up returns after their winning years. The result: the managers had a respectable annual average return of 16.2 percent compared to 24.3 percent for the index. The unmanaged index beat the hottest hands in the business by 50 percent. Most of the reason for that figure is that even the best managers can’t consistently repeat their best year, much less beat the index on a regular basis. Bogle cites research that has shown that funds that “rank in the top 20 in a given year have, on average, ranked 240 (of 554 funds) in the subsequent year.” That means the best funds become average performers sooner rather than later, or “regress to the mean,” in the lingo of statisticians.

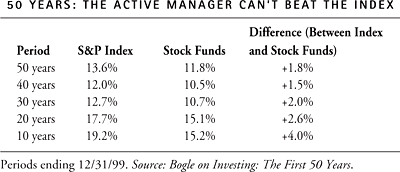

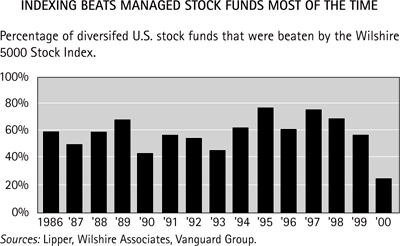

• Over long periods, the index wins and managers lose. By virtue of having to justify higher costs in the form of higher returns, managers simply can’t beat the index until they both outperform and donate their services. Bogle actually trumpeted in one of his speeches, “fellow indexers, be of stout heart: active managers as a group never win.” Bogle looked at ten-year periods going back fifty years to see if he was right.

• Expenses have an even more dramatic impact on income investments. Because bonds and cash equivalents emphasize income and not capital appreciation, expenses eat into returns directly, and often severely. Bond funds differ little from category to category. A money-market fund is going to primarily buy bonds that mature in under a year. An intermediate-bond fund will have bonds with an average maturity of about five years. There’s really little management involved. So expenses make a huge difference in total return. For my short-term savings, I recently began checking out yields on bond funds to enhance the paltry 3.1 percent return I was getting on my money-market fund. I was willing to take a little bit more risk, so I started comparing intermediate-term bond funds that invested in a combination of corporate and Treasury bonds. I found two funds I liked: A fund rated highly by all of the rating services yielding about 6.7 percent and a fund yielding about the same representing an index of intermediate bonds. The index fund had an expense ratio of 0.21 percent; the top-rated fund had an expense ratio of 1.75 percent plus a 3.75 percent sales charge. Which fund do you think I chose? As Bogle warns, “Never, never invest in a bond fund without knowing its expense ratio.”

• There’s a powerful relationship between risk-adjusted returns and costs. Bogle did a study in 1998 that he hoped would show the relationship of risk to costs. He published this highly readable report in The Journal of Portfolio Management. Although the results of the study reinforce what he had been saying for years—lower costs translate into higher returns—he found a side benefit of lower-cost investing. “The funds in the group with the lowest expense ratios have the highest net returns. At the same time, they assume a nearly identical level of risk (volatility), and therefore provide distinctly higher risk-adjusted returns.… Now we seem to be on to something important. With risk astonishingly constant, high returns are directly associated with low costs [italics his].” He further discovered that “each 1% increase in the expense ratio has, on average, reduced the net total return earned by shareholders by 1.80%.” Moreover, actively managed funds tend to be more volatile than index funds. According to Morningstar, the average domestic equity fund was 15 percent more volatile than the Vanguard 500 Index Fund over the past decade. Add to that the fact that 85 percent of all large-cap index funds underperformed the S&P 500 Index over the past years and you have one of the best arguments for index funds as a “core” holding (one you needn’t change for decades) in your portfolio.

• Index funds are more tax efficient. The largest index funds have almost no turnover, meaning they don’t generate much in the way of capital gains. Compare that to turnover of actively managed funds—often exceeding 100 percent—and you have a formula for partially reducing your tax bill.

It All Comes Down to Risk and Return

I am not canonizing John Bogle, nor should you accept everything he says as gospel. He has been beating the drum for index funds all these years because Vanguard has been selling them and was building a market niche, which it found in a big way. And now that Bogle is no longer running the company and is free to say anything he wants about the industry (which he has throughout his career anyway), he does so with impunity and investors love it. He even has a staunch following among investors, who proudly call themselves “Bogleheads” when they leave messages on the Internet. You can’t argue, however, with the fact that the vast majority of money managers can’t beat a market index most of the time. It can’t be done.

Burton Malkiel, the esteemed Princeton economics professor, proved the “also-ran” nature of mutual fund managers. Malkiel looked at the top 20 mutual funds from 1990 to 1994 and calculated the returns of the funds over the next five years. Over the initial four-year period, the funds managed to beat the S&P 500 Index by an average of 9.2 percent. Had you invested only during that period in those funds and pulled your money out and invested in U.S. Treasury bills in 1995, you would have had a good reason to be proud—and wealthier. In the next five years, however, those top funds trailed the market average by 2 percentage points a year. Malkiel found similar results in the 1980s.

It’s clear that you are taking more risk by staying with a poorly performing managed fund. That’s one risk that the managed mutual-fund business would prefer that you ignore. Sure, there are funds and managers that beat the index every other year. You can even go through Vanguard’s large stable of funds and see scores of examples of their actively managed funds that are beating the appropriate index fund. Does that contradiction build a case for managed funds? No. In time the troll named “regression to the mean” catches up with even the best managers and they become average or less-than-average performers.

What about the years in which the indexes themselves represent overall poor returns for stocks or bonds? Can’t active managers beat the indexes then by avoiding stocks heavily weighted in the indexes posting negative returns? After all, in the first half of 2001, an awful time for almost every stock index (especially those measuring large-cap growth), 59 percent of stock mutual funds were beating the S&P 500. Keep in mind, however, that these “stock pickers” are not identified. Are they primarily value-oriented funds that avoided technology stocks? Are there funds that beat the average simply by losing less money than the index? As Mark Twain once said, there are “lies, damn lies and statistics.” In the end, we’re all average. In the money management world, most are less than average over time.

Nevertheless, most investors will succumb to the wisdom of the broker who calls them up and offers them the next best thing, believing the mystical incantation of someone who doesn’t know any more about the market than you do. They will try to impress you with the depth of their firm’s research and the thousands employed to sort out the hidden lexicon of profit.

“So the vast majority of analysts and money managers continue to put in long hours honing their analytical skills and looking for that one insight that will give them an edge,” writes John Rubino in Main Street, Not Wall Street (Morrow, 1998). “For most professional money managers this has become an exercise in futility. And this futility has become the dirty little secret of the investment world.” Indexing offers you an advantage that no single money manager can give you: as much of the market as you want at low cost.

The King and the Bishop

Although the index fund was clearly not invented in Denmark, I have a Danish fable that relates to the deception of appearances. A bishop had once written on his gates and doors, “I am the wisest man on earth.” When word of this boast reached the king, he was infuriated and demanded that the bishop account for his wisdom. When the bishop visited the king and assured him that he, the bishop, was the wisest man in the land, the king sent him home and bade him return in four days to answer four challenging questions to prove his wisdom.

When the bishop arrived home, he took off his mitre and sobbed, knowing that if he couldn’t answer a single question he would surely lose his head. At that moment, a shepherd was passing by and listened to the bishop’s story.

“Give me your clothes and your mitre and I will visit the king pretending to be you. If I can’t answer the king’s questions, he will only take the life of a lowly shepherd and not a man of God.”

So the shepherd was on his way and the king was ready with some difficult questions.

“How fast can I travel around the world?” the king asked, peering at the shepherd.

“Why, your majesty, if you have a horse that can follow the sun, it will take you twenty-four hours.”

The king blinked at the shepherd’s cleverness, but couldn’t deny his answer.

“Now how far is it from heaven to earth?” The king glared.

“Why your majesty, I am certain that you are an expert stone thrower, so it’s only a stone’s throw.”

Taken aback by the shepherd’s flattery, the king launched one more question.

“Can you tell me how much I am worth?”

“You are only worth twenty-eight pieces of silver. Jesus was sold for thirty pieces and I would think he was worth at least two more pieces than your majesty.”

Blustering, the king shouted, “Can you tell me what I am thinking?”

“You think that I am a clever bishop, but I’m nothing but a shepherd.”

The king then spared the bishop and made the shepherd his chancellor.

* * *

Cleverness is always rewarded, but in investing, it’s honesty, modest expenses, and performance that really count, so don’t be hoodwinked by appearances and claims.