CHAPTER 11

Putting It All Together: Portfolios for Any Market

There are many good reasons why an investor might decide to sell common stocks. He may want to build a new home or finance his son in a business. Any one of a number of similar reasons can, from the standpoint of happy living, make selling common stocks sensible.

—Philip Fisher

In the ever-expanding sphere of the ego, the space around the self is boundless. It knows no limits since the universe itself is infinite and mortality is keeping pace with medical technology. It is clearly a time of energy, sound, and furious activity in the global economy. We all want to be part of it. Some of us shared in the wealth by taking our home equity to build a larger home; others invested in the stock market. We felt wealthier because of heftier 401(k) balances, six-figure home-equity stakes, the cars in the driveway, and the vacations to the Caribbean. Ego space, however, is abstract, a derivative of expectation and speculation. We build the big homes because we think we’ll be able to afford the mortgage, taxes, and upkeep over time. And we don’t even consider the thought of downsizing, except maybe when the kids are out of the house or it’s time to live near a golf course in Florida. Like outer space, ego space is filled with all sorts of perils. There’s lots of radiation from the glare of the small screen, screaming at us to buy or sell without rhyme or reason. If we don’t have the right insulation around us, we’re fried. There are meteors and asteroids and the sheer vacuum of space itself, so we have to bring our own oxygen. Only when we prepare for the perils can we truly mitigate the risks.

Speaking of risk, having written five books on investing and countless magazine articles, I have to confess that I have made many investing mistakes. I invested in sector funds and moved out at the wrong time. I panicked and pulled out of stocks during the October 1987 crash and missed some of the rebound. I invested in gold-mining shares after there was a spurt in inflation. When inflation went away, I pulled out too late. I invested in foreign emerging-markets funds after their best year, then stayed in too long during their dog years. I invested in a portfolio of solid blue-chips with DRIPs, only to pull out when prices were down and I could’ve reaped some incredible gains if I just held on for a few years. And worst of all, I concentrated too much money in technology and telecommunications, ignoring vast pieces of the market. So I have dwelled in ego space and it is not a prosperous place.

The most obvious problem with my family portfolio was that (1) I neglected watching it carefully year to year (moving twice and having a baby won’t help your attention span), (2) I failed to state our long-term objectives and stick to them, and (3) it just wasn’t diversified. It took me several months of research to figure out the next move. Here’s what we did (and you can do this with your own portfolio in principle):

Prune the losers. I had one stock that we had held on to for five years. I bought at $2.50 and it languished at $1.50. It was a technology company that was producing MRI machines, but the company never posted a profit. It looked good on paper. However, management wasn’t interested in boosting shareholder value, so I sold it at a loss. We also looked at our stock mutual funds, which were down more than 20 percent. We decided that this was more than we were prepared to lose, so we exchanged those shares for shares in other stock funds (read on).

Eliminate concentrated risk and duplications. Both my wife and I had several technology or health-care sector funds. That concentrated the risk in two industries, which are both extremely volatile. The technology funds got hit the worst, so they were sold and shares were exchanged for other, more diversified funds. Again, the volatility was too much for us. It was like we were parking our aircraft carriers in Pearl Harbor. At the time, we thought that putting more assets into two booming sectors would increase our profits, when in reality it gave us greater exposure to losses when the market turned. I also had a SEP-IRA in a zero-coupon bond fund, which focused risk on one type of bond that only profits from capital appreciation (and no interest) when long-term interest rates fall (they didn’t). So, after two years of flat performance, I moved those shares into another fund. The biggest mistake I made was not considering my wife’s holdings and mine as one portfolio, so it was constructed willy-nilly without regard to style, capitalization, or risk concentration. Now all of our 401(k) rollover IRA, SEP-IRAs, Roth IRAs, and Education IRAs for our two daughters are looked at as a whole portfolio. We also consolidated nearly all of the accounts with a low-cost mutual fund company that allowed us to monitor the portfolio on-line. All of the funds carried some of the lowest expense ratios in the business and no sales charges.

OUR NEW ALLOCATIONS | ||

Style/Capitalization |

| Percentage Allocated (approximately) |

Mid-/small-cap value stocks |

| 30% |

Large-cap value stocks |

| 20% |

Large-/mid-cap growth |

| 20% |

Small-cap growth index |

| 10% |

Equity-income (blend) funds |

| 5% |

Health/financial sector funds |

| 5% |

Global stock fund |

| 5% |

REIT index fund |

| 5% |

What styles and capitalizations did we ignore? After a careful look at our portfolio, I was surprised that nearly all of it was in large-cap growth stocks. So I took the money from the funds we sold out of and invested in the new ones here.

Restructure the income portfolio. This took even more time and consideration than the stock portion of our portfolio. Before our reallocation, we kept 100 percent of our short-term cash in a tax-free money-market account and checking account. We only kept enough money in the checking account to pay monthly bills; the surplus went right to the money-market account for funds we would need within two years or less. Having learned the lesson from concentrating too much risk in similar stock funds, I decided to create another tier for our income needs: money we wouldn’t need for more than a year and less than five years. In this part of our income portfolio, we agreed to take a little more risk, but quantified that risk to be a potential loss of no more than 5 percent of principal in exchange for a greater return. So we took 25 percent of the money sitting in our money-market fund and put 65 percent of it into a short-term bond index fund and 25 percent into a total bond-market index fund investing in a variety of corporate and government bonds. These funds yielded between 5 percent and 6.25 percent. That way, we mixed low and moderate-risk bonds within a small portion of our income portfolio. Why did we take 25 percent of the money out of the money market? We figured what a year’s worth of expenses would be and invested the extra money at greater risk because we wouldn’t be using the money for more than a year.

Since we anticipated—and planned for—a drop in our federal tax bracket, the tax-free money-market fund no longer made sense as it was barely yielding 2 percent in tax-equivalent dollars (the yield subtracted by the marginal tax rate). After subtracting the expenses for managing this fund, we were losing money after inflation. So I searched the Internet for the highest-yielding, lowest-cost money-market fund available (see www.imoneynet.com) and moved most of our short-term money into a new account yielding about 3.25 percent, boosting our returns by more than 50 percent. I even found a large, reputable money-fund manager that was waiving all management expenses (a fairly common practice in the business) until 2006, so that also boosted return.

In addition to the income portfolio restructuring, we also refinanced our mortgage. After months of negotiation and delays, we were able to negotiate a no-escrow mortgage at a rate a full percentage point below our previous mortgage. That saved us $100 a month and allowed us to invest the money we needed for taxes in an interest-bearing vehicle such as a U.S. Treasury note, which would not only guarantee the principal, but pays us interest (as opposed to not earning a dime in the bank’s escrow account). The refinancing alone saved us $1,200 a year.

The bear market, in retrospect, prompted us to think carefully about how to best allocate risk. In boom times, you tend to be floating in ego space, hallucinating about the dancing bubble bear, so none of these ideas occur to you. All of what we’ve done is hardly the perfect model for what you need to do, although we managed to balance risk within our portfolio and enhance returns in every way possible. Everyone is different. You need to start, as I mentioned in chapter 2, by gauging what your short-term needs are and making sure you have enough cash for emergencies and ongoing expenses for at least a year. This is your “safe” money, which you put into vehicles that preserve principal. Beyond that, you are investing for intermediate needs and ratchet up risk accordingly.

You will be able to outlast bear markets if you keep your short-term income safe and diversify your intermediate- and long-term investments across styles, capitalizations, sectors, and asset classes (stocks, bonds, real estate, cash). And keep in mind the risks in your own life. Is your job situation unsteady? Are you in an unstable industry? Are you self-employed? Find out how much you are spending on monthly items and see what can be cut back. Keep enough cash on hand to get you through the down cycles in your business. Also quantify your risk in every fund and stock so that it’s spread out among high-, moderate-, and low-risk vehicles. Know how much you can lose in each fund or stock by looking at their worst years in addition to the winning years. All of this information is available from your public library and will take you only a few minutes to digest.

After you do your homework, you can build a bear-proof portfolio and not worry about it. There are a number of misconceptions, however, that get in our way as we navigate ego space. The colliding asteroids of emotion and faulty logic are immense when it comes to the market, but they can be overcome. As we conclude our journey, I’d like to suggest some ways of dealing with emotional barriers and making changes.

Overcoming Barriers: Asking the Right Questions

Much of what is known about investment risk is clearly detailed in every mutual-fund prospectus, which, unfortunately, most people neglect to read. It’s an important starting point for understanding what could go wrong and how to avoid trouble. If you are scouting an individual company, read the company’s annual report, “10-k” SEC filing, and any independent analysts’ reports from Value Line, S&P, Morningstar, and other firms.

• Pay attention to objectives. Every mutual fund must tell you what the fund is trying to do. Is the manager aiming for growth through capital appreciation or income or both? What kinds of stocks are they buying? If you need income, you have no business in a stock fund seeking capital appreciation. Know where you want to be and see if the fund’s objective matches yours. You can also discuss this directly with a broker. Is the stock or bond appropriate for your objectives and risk tolerance?

• What are the investment strategies? What kinds of securities will the fund buy? How will they select the securities? Are they using a value or growth approach? What percentage of the securities will be allocated by sector or country? Feel free to call the fund company or manager to get your questions answered. They will talk to you.

• Special investment risks. Pay special attention to this section of the prospectus. What’s the downside? What kinds of securities may go belly up in a storm? What percentage of the portfolio will be comprised of the riskiest assets? How much more volatility will special risks add to the returns of the portfolio?

• Who should invest? This language is usually fairly clear. Is the fund or security low, moderate, or high risk? What does that mean for this fund? In terms of a bond fund, you can ask what will happen to the value of this fund if interest rates rise 1 percent. Or with stocks, what happens to this fund if there’s a downturn? How does the fund compare to the index? Explain why you are investing and what you are seeking. How long do you have to invest? Short-term goals are best served through funds that preserve capital; long-term goals are best served through higher risk and capital appreciation.

• What are the expenses of the fund? Ask for the expense ratio of the fund. Compare it to average expenses for similar funds. What are the commissions, back-end loads, marketing charges (12b-1 fees), and other expenses. What are those costs over time? They make a big difference if you don’t plan to sell for a long time.

• How can you get your money out? With mutual funds, you can arrange wire transfers to your savings or checking accounts, write a check, or request a redemption. With DRIPs, it gets a little tricky because you have to go through a transfer agent and it may take several weeks. If you ask these questions, you have a greater likelihood of matching the fund or security to your investment goals.

What Misconceptions May Interfere With Your Investment Success?

It’s also helpful to know what kinds of thought processes may interfere with your asking the right questions and making the right decisions. The field of economics called “behavioral finance” seeks to explain investor psychology. Led by the University of Chicago’s Richard Thaler, this subspecialty has found a number of consistently dangerous behavior patterns in the ego space of investors.

Investors often employ flawed logic in making decisions, which hastens the loss of their money. Here are a few trouble spots to watch out for:

Holding on too long. We tend to hoard losers and sell off winners. The value school of investing, for example, takes the opposite tack. You need to keep your winners and shed your losers. Most people hope to recoup their losses and buy more shares of a loser rather than sell it and buy a stock that’s growing. If you have a loser—a stock that’s down more than 20 percent—sell it. Uncle Sam will let you write off some of the losses.

Buying high, selling low. As I mentioned in chapter 9, this is a perennial fault of investors largely based on the “bigger jackpot effect.” When investors see a stock move skyward, they assume that it will continue forever, no matter how overvalued that stock may be. Just because other investors assign a high p/e or high stock price doesn’t mean it’s worth buying. And once they buy the high-priced stock, they stay put for a while until the inevitable decline, sell, and lock in the loss, or they hold on, thinking they will get back to the price at which they bought the stock. If you have the gumption—and all of the fundamentals of a stock look good—stay the course. How long will you wait? If nothing happens in a year, will you sell? Take a look at your portfolio once a year. If you have losers, prune them.

Believing stock analysts. “Hot” research analysts—the talking heads you see on TV who work for brokerage houses—are there for a reason. They are there to sell you on stocks, not to share with you any profitable insights. They are pitchmeisters who are there to manipulate you into buying so that the price of their recommended stocks goes up. And it’s no coincidence that the stocks they are pitching are the same stocks sold by their brokerage house. It’s amazing that this persistent and undeniable conflict of interest hasn’t gotten more people in trouble. All too many people suspend reality when they look at the small screen, the ultimate window to investor ego space.

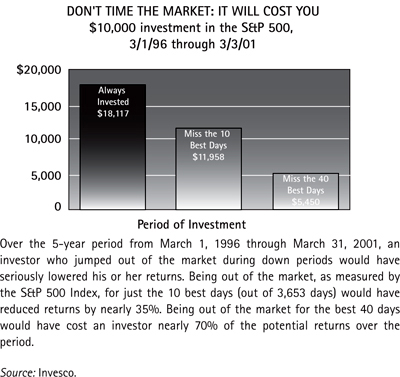

Knowing the “right” time to invest. There are always investors who claim to know when the market will “turn.” So they plunge in and out at the wrong times. Not even Alan Greenspan knows what’s going on with the stock market. Either stay fully invested in your portfolio or stay away from it entirely if you have a short-term focus.

Getting the best advice. I’m constantly amazed at how many extremely educated people are willing to take advice from a complete stranger on what stock or mutual fund to buy. Investing is a very personal matter. You have to know yourself before you invest. Nobody else can plot the right course for you, your family, or the amount of risk that will allow you to rest easily.

Overtrading costs too much. Let’s say you are completely enveloped in your investor ego and are convinced you know every time a stock is overpriced or headed for a fall, or the market is turning. Every time you act on your conviction, you will certainly pay a commission to your broker and taxes on your profit (if you have them). Had you just done quality research and held on to the stocks for twenty years, you would have done much better. Morningstar Stock Investor found that, after taxes, $10,000 invested in a “buy and hold” stock portfolio netted you $77,170, but only $52,546 if you sold each stock after one year. You can become overconfident and trade too much simply because you trust the (often bad) advice of others. “Overconfidence-based trading is truly hazardous to accumulating wealth!” warns John Nofsinger in Investment Madness: How Psychology Affects Your Investing … and What to Do about It (Prentice Hall, 2001).

All of these factors add to the risks that you can easily avoid. If you don’t want to guess where the market is going, buy a mix of index funds and hold them. Only sell them if you need the money. If you want to add some spice to your portfolio, choose from any of the managed funds I’ve recommended in this book. While it sounds counterintuitive, buying and holding stocks and funds is one of the simplest, no-brainer ways to wealth because your risk goes down over time. Perhaps one of the best writers on the subject of risk is Peter Bernstein, who wrote the classic Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk (Wiley, 1996). Bernstein, a money manager, profiled the history of risk, risk management, and insurance in his noteworthy book. One passage stood out that summed up the field of behavioral finance:

A growing volume of research reveals that people yield to inconsistencies, myopia, and other forms of distortion throughout the process of decision-making. That may not matter much when the issue is whether one hits the jackpot or the slot machine or picks a lottery number that makes dreams come true. But the evidence indicates that these flaws are even more apparent in areas where the consequences are more serious.

Knowing When to Sell

If you want to participate in a triathlon, you know that you’re going to be doing a lot of running, biking, and swimming to get in shape for the actual event. If your knees get sore or you pull a muscle, you have to stop training for a while. The discipline of investing is much the same, only investors spend more time on their bodies than on making the right decisions with their money.

Bear markets prompt a lot of serious thinking about investment objectives, timing, and fine-tuning portfolios. I know it did for my wife and me and all of my family and friends. The plunge in the market forced us to make some changes that we wouldn’t have considered in a booming market, changes that we should have been thinking about all along. Knowing when to sell is more important in many ways than knowing when and how to buy. Americans can buy anything. It’s as easy as eating ice cream. Selling, however, is not something we are good at. It’s like getting rid of a favorite possession. We want to hold on no matter what. Here are some guidelines for stocks and mutual funds that will prove useful in any market, so that you don’t have to hold on to losers:

• Set your loss limits. Brokers call this “stop-loss.” You set a price at which you will sell. For mutual funds, you have to look at percentage losses. How much of a loss will you tolerate? Know the answer before going in. Look at the fund’s performance during its worst year. Would you stay invested if you were in the fund during an off year? Maybe the fund is too volatile to begin with, and you have no business being in it. Research before you invest.

• What has changed? Sometimes companies hit a rough patch in the economy or their sector. When oil prices go up, airlines and trucking companies get clobbered because their cost of doing business goes up. When commodity prices rise, a number of companies get hit hard. Is there something fundamentally wrong with management? Motorola, for example, bet on the wrong standard for cell phones and they lost tremendous market share. If something can be fixed, is management fixing it? Most corporations’ standard response to trouble in their business is to cut costs and lay off people, but they may be missing the core problems. You have to be tough in asking the questions about whether a company or fund’s woes are short-term or long-term.

• Bad news travels fast. If one company reports lower earnings in a line of business, chances are others will, too. Unless a company is broadly diversified, one suffering sector can pull them down. Ideally, you want a company or fund participating in a growing business, but that’s hard to find in a slack economy, so you may need to sell if there’s no hope on the horizon.

• Have a sell target. If you have a target for short-term appreciation, and you don’t intend to invest in the stock or fund short term, then set a sell target and stick to it. If the stock doesn’t hit the target by a certain time, sell it.

• Are fundamentals getting worse? Is net income on a downward trend? Are sales decreasing? Are earnings per share dropping? Is the company losing market share? Are operating margins falling? These are all signs that you should be selling.

• What are the insiders doing? By insiders, I mean executives of the company. Are they fleeing the ship by selling huge amounts of shares? Each company is required to report that information to the Securities and Exchange Commission. It’s also listed in the Wall Street Journal, in Barron’s, and throughout the Internet. Don’t buy or sell based on “inside” information; it’s usually somebody touting a stock with an undue sense of self-importance.

• What is inflation doing? Double-digit inflation ravages the bond and stock markets in different ways. With bonds, inflation pushes up interest rates and depresses bond prices. For companies, they must shell out more for materials, operating expenses, and labor and can’t always recoup those expenses by charging more to their customers. So stock prices get hurt as well, although small stocks fare somewhat better than bonds in an inflationary economy. As John Neff notes, “Inflation becomes a bogeyman that can distort all of your painstaking, bottom-up calculations. Double-digit inflation devastates fixed-income markets and, in consequence, ravages equity markets. A whole new standard emerges.” If inflation rears its ugly head, the last place you want to be is in a long-term bond fund. In an inflationary recession, this can be disastrous.

• Did the company’s product become a commodity? If you had invested in a mutual fund dominated by cell phone makers or computer resellers, you know what happened. Every cycle of new technology makes yesterday’s products obsolete. Make sure you are investing in innovators on the manufacturing and marketing side or find fund managers who are good at finding leading-edge companies.

• Don’t fall in love. With a stock, that is. Capitalism makes fools of us all. Markets change, technology changes. Not every company or fund can keep up with the new product cycles. You don’t know more than the market does.

• Did your mother ask about the stock? I always know the Chicago Cubs are headed for a fall when my mother mentions them. Of course, the Cubs always fall and she only mentions them because she’s sick of my dad complaining about them, which he’s been doing for the last fifty years. Unless your mother is an investor, you don’t want to see your stock’s CEO on the cover of Time, Newsweek, or U.S. News & World Report. That’s a death knell. Stocks and mutual funds can get too popular. With mutual funds, the main problem is trying to invest all the money pouring in after a winning year. They can’t get it invested fast enough, so they either close the fund or make mistakes.

• Sell to take profits. If the market’s up 20 percent, take some profits and put them in cash or another stock that’s underpriced. Don’t pay any attention to the general market, however. Pay attention to the companies and funds you own.

• If dividends aren’t there, time to dump. If you bought a fund or stock because it paid dividends, it should be raising its dividend payout consistently every year. There are plenty of companies with excellent dividend payout rates, so you don’t have to stay with a loser.

• Never sell for tax reasons. You may be avoiding the real reason why you need to sell some shares: they’re losing money. Keep in mind that the more you trade, the higher your transaction costs (and taxes, if you are selling winners), and the lower your total return.

• You’re not going to break even. This is one of the greatest deceptions in holding losers: the idea that if we hold a fund or stock long enough, it will get back to where we bought it. If you’re waiting for that to happen in a mutual fund, fund management is charging for expenses and transactions, so you just get deeper in the hole. With stocks, it’s better to take the loss and put the money into cash than hold onto a position that’s earning nothing.

• Forget about short-term results. Richard Thaler found that we tend to give more weight to recent performance than historical returns. As I cited in the last chapter, when tech stocks were at their peak in 2000, more than half of the new money in tech funds was coming in. I would bet that most of those investors didn’t bother to check to see how volatile those funds were over time. The opposite kind of investor doesn’t take enough risk because of “loss aversion,” the chance that they’ll lose a dollar or two in today’s market, so they ignore the fact that stocks are the best performing class of financial assets over decades—and their chances of making money are 80 percent or better.

• Don’t watch the price every day. If you are watching the tube every day, it will drive you nuts. Evaluate your portfolio once a year. As Philip Carret advises in The Art of Speculation (Wiley, 1997), “It is conventional advice to the investor that he should go over his holdings in search of weak spots at least annually.”

What We Know about Investing: A Review

We need to do a little review of the field trips we’ve taken. Here’s what we’ve covered so far:

1. Stocks beat bonds over time, but not all the time. Long-term stock returns may be lower, so we need to prepare for that possibility by diversifying our stock holdings and keeping enough cash for our needs.

2. Cash and bonds are essential for short-term income needs—and an occasional buffer from the stock market—but won’t beat inflation over time (stocks will). Even a little real estate helps in tempering risk in the portfolio.

3. Mixing bonds and stocks will reduce overall risk, particularly in down markets. A sensible mixture of 60 percent stocks to 40 percent bonds, in a “balanced” mix or mutual fund, will help get us through bear markets.

4. Fine-tuning the combination of stocks and bonds will mean looking for both kinds of vehicles in a “value” perspective, where securities are bought at bargain prices and held for the long term.

5. Over the long term, the value perspective does the best in identifying stocks and bonds that will perform well in any market. We can either do the research ourselves or hire top fund managers.

6. Investing in smaller-cap and mid-cap stocks over time will further enhance returns with considerably lower risk over time in a broadly diversified portfolio.

7. Stocks and bonds from overseas will also lower the risk profile of our portfolios because foreign markets may move in different directions than domestic markets.

8. We can build a diversified portfolio ourselves through dividend reinvestment plans (DRIPs) and do the research ourselves on a portfolio of individual stocks.

9. If we want to boost returns, we can invest in specific sectors of the stock market, but only if we are committed to investing in these vehicles for at least ten years and make these funds part of a diversified approach.

10. By understanding how excessive costs chew up returns over time, prudent investments in index funds can reduce expenses, lower risk, and give us broad exposure to every kind of stock, bond, and real estate market.

Okay, that wasn’t so bad, was it? It’s easier than doing your taxes or worrying about Social Security. These principles are fairly universal and you can employ them as long as you like. They are based on the collective wisdom, insight, and research of some of the finest minds in investing. And they work over time. All you have to do is put the plan in motion and hold on through the down cycles. Unfortunately, most investors will not stay the course and continue to trade on tips from their brother-in-law, “someone who knows,” and brokerage house analysts touting something their company already owns and is trying to hawk to the masses.

Investing is a discipline. In order to be successful, you start with a few guidelines, but need some insights into human nature before you can proceed. You know your needs fairly well, so you need to find a portfolio that creates harmony with the rest of your life, an ecology that is sustainable for the amount of risk you can take. So here are a few suggestions for how to do that:

In Search of the Right Allocation: My Portfolio Advice

When a fisherman prepares his line, he has a specific lure or bait he uses to catch a certain type of fish. Bullheads won’t go after flies. Trout don’t like plastic worms. Your portfolio needs to be properly baited to catch the right returns. Now it’s a question of which funds to select and what percentage of which type will work for you (regarding individual stock allocations, refer to chapter 8 for some broad suggestions).

The conventional wisdom in investment research is that 90 percent of the variability in returns is due to asset allocation, that is, the portions of your portfolio invested in specific vehicles. For example, a 100 percent bond portfolio will produce returns that are far different from a 100 percent stock portfolio. Since diversification is the best way to go for every kind of investor, I have some suggestions as to how you can produce returns that are acceptable given your level of risk tolerance.

With mutual funds, the question of consistent returns is always a nagging problem for investors. Some 40 percent of the variation in returns among similar funds is explained by asset allocation. Two similar funds may invest in large-company stocks, but one may turn over the portfolio faster, have a higher expense ratio, or lose a top manager. So you need to look for low-expense funds with performances that beat their peers over time. At least five years’ worth of performance information is a good starting point; ten years or more is better.

The following portfolios are structured for investors at different points in their lives with varying tolerances for risk. You can tailor the percentages any way you like. You can use the funds I’ve suggested in this book in the “fund type” slots—if the funds’ risk profiles truly match your risk tolerance and objectives. You can mix and match funds to construct the portfolio that’s best for you.

NERVOUS NELLIE SAVER PORTFOLIO

Profile: You don’t like volatility, but need income short-term, capital preservation, and some growth.

Fund Type |

| Allocation |

Money-market fund |

| 40% |

Short-term bond fund |

| 10% |

Intermediate-term bond fund |

| 10% |

Equity-income/balanced fund |

| 20% |

Large-cap value fund |

| 20% |

EMPTY NESTERS

The kids are out of the house, college bills are paid, everyone’s in good health, and you need to save for retirement in 10 to 15 years. Growth is needed, but capital preservation is also important.

Fund Type |

| Allocation |

Money-market fund |

| 10% |

Intermediate-term bond fund |

| 10% |

Equity-income or balanced fund |

| 20% |

Small- or mid-cap value fund |

| 20% |

Large-cap value fund |

| 20% |

Large-cap growth or sector fund |

| 10% |

International stock fund |

| 10% |

LET IT RIDE!

Retirement is at least 20 years away and growth is paramount, so above-average risk is tolerable. Short-term expenses can be covered in a money-market fund.

Fund Type |

| Allocation |

Small-cap value |

| 30% |

Small- or mid-cap growth |

| 20% |

Large-cap growth/value |

| 20% |

Sector |

| 10% |

International |

| 10% |

Real estate |

| 10% |

GOAL-ORIENTED: SHORT-TERM SAVINGS

You are saving for a downpayment on something big within five years (home, college, etc.). Market risk needs to be at the absolute minimum and capital preservation is paramount.

Fund Type |

| Allocation |

Money market |

| 60% |

Short-term bond |

| 20% |

Intermediate-term bond |

| 10% |

Government agency bonds (short) |

| 10% |

FDIC-insured CDs or Treasury notes may be substituted for short- or intermediate-term bonds if capital preservation is paramount. | ||

MIDDLE OF THE ROAD

Somewhat between “Let It Ride!” and “Nervous Nellie,” this portfolio seeks long-term growth with at least a 15-year horizon. This is for investors who want low- to moderate-risk capital appreciation and no income (outside of short-term savings) for now.

Fund Type |

| Allocation |

Equity-income/balanced fund |

| 20% |

Small- or mid-cap value |

| 20% |

Large-cap value |

| 20% |

Large-cap growth |

| 20% |

International |

| 10% |

Real estate |

| 10% |

SIMPLICITY INDEX

For long-term investors with at least a 15-year time horizon, this allocation won’t need to change unless your needs change. Risk is average across the board. Investors whose needs reflect the profiles of the other portfolios can use index funds depending on their objective.

Fund Type |

| Allocation |

Total market |

| 50% |

Small-cap value |

| 20% |

International |

| 10% |

Total bond market |

| 10% |

Real estate |

| 10% |

Not Another Fable

This story is about a young couple who bought a house in the country and two horses, and they were doing really well with a six-figure household income. The house was a hovel, but they fixed it up. The horses ran away now and again and the home remodeling got to be exorbitant, but our couple was making decent money in their jobs (the wife had her own thriving software business) and the stock market boomed during the ’80s and ’90s, so they spent the money on the ramshackle house and the husband continued to commute up to four hours a day to and from their country cottage.

Then a bright, blue-eyed baby girl named Sarah Virginia came along and the earth moved. Suddenly she needed friends to play with and a decent school district, and the horses had to go because they were downright dangerous because when Sarah became a toddler she liked to run through the horses’ legs, scaring the parents half to death.

So our couple sold their little home in the country, sold the horses, and built a new house with twenty-four hundred square feet and a basement in a promising community with plenty of educational choices, a trail system, beach, organic farm, and lots of little kids, particularly little girls. They were happy for about a year and a half, even welcoming another blue-eyed baby girl, Julia Theresa, into the world. Their property tax bill was more than twice what they were paying on the old house, which had no basement or garage, but they figured they could easily cover it with their income. They were willing to pay the premium for all of the amenities and the lovely neighbors.

Then the husband’s company disintegrated because his boss had spent all of the company’s money and then some on a Web site that didn’t bring a penny in the door. First the Web site was shut down and lots of people lost their jobs. Then the husband lost his job and health insurance after fifteen years of steady employment in the middle of a recession. The stock market continued to have seizures and suddenly our couple didn’t feel quite so wealthy anymore. Unfortunately, the wife had sidelined her business to spend time with her beautiful daughters, so she was worried, too.

Our family, fortunately, did okay, because they had been saving all along to avoid financial catastrophe, putting a year’s worth of expenses into a money-market fund and moving their long-term savings into safer, less-aggressive mutual funds. They had also been investing all along in individual stocks through a family stock investment club and fully funded their SEP-IRAs, 401(k)s, Roth IRAs, and Education IRAs (read my Kitchen-Table Investor for more details). When the husband lost his job, they cut back their spending to the absolute minimum and refinanced the mortgage.

Now the family is at home together twenty-four hours a day, the daughters are being educated by full-time parents, who work side by side during the kids’ nap time. And that’s not the end of the story, for this was the family’s preferred mode of living all along. We’re going to pull through.

* * *

You can choose the life you want. It can be done. A Harvard study of 724 men over a sixty-year period found that the men lived to a ripe old age largely by choice. They generally chose the path of “moderate alcohol use, no smoking, regular exercise, appropriate weight and positive coping mechanisms.”

Harmonious living is an integral part of a sound personal ecology—one that is balanced between work, family, community, and leisure. When it comes to investing, you need moderation as well to get you through the growling times of crisis, doubt, depression, and indecision. It all starts with a sober attitude toward risk, a close focus on your investment goals, and a diligent savings plan. The rest is a saga of your own making, lovingly crafted to your life in ways that are important to you.