CHAPTER 4

Bargains and Income: Stocks and Bonds That Stand Up during the Storm

Every investor should be prepared financially and psychologically for the possibility of poor short-term results. For example, in the 1973–74 decline, the investor would have lost money on paper, but, if he’d held on and stuck with the approach, he would have recouped in 1975–1976 and gotten his 15% average return for the five-year period.

—Benjamin Graham

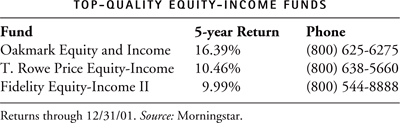

Clyde McGregor is built like a football lineman, and possesses the intellect of a college professor. An occasional golf and tennis player, he used to play basketball, but I wouldn’t want him setting a pick against me. With Edward Studzinski, he has managed the Oakmark Equity & Income Fund to generate income while preserving and growing capital. Studzinski came on board in 2000, but McGregor has been running the fund since 1995. Like the Pax World Balanced Fund, Oakmark Equity & Income has at least 25 percent of its holdings in bonds; however, the fund parts company with Pax in its approach. As stalwarts in the fine Oakmark team, McGregor and Studzinski run what the industry calls a “value shop.” They are bargain hunters first and foremost and will do endless amounts of research to find their bargains.

It’s hard to classify McGregor’s fund since it does so many things well. It is simultaneously generating income, producing growth, and keeping volatility down. McGregor’s team isn’t much interested in where the economy is headed, the hottest sector, or even the latest technology. They swim on the bottom of the ocean and see what’s floating down, hoping that it will rise again. Fund-rating services are hard-pressed to put a label on the fund. Morningstar calls the fund a “hybrid” or “large-blend” fund, which tells investors nothing about what the fund does or how it performs. The more traditional label is “equity-income,” a slightly better description that tells investors it splits its portfolio roughly between 75 percent stocks and 25 percent bonds, but not always. Oakmark provides a somewhat better description: “The fund invests for high current income and preservation and growth of capital. It is designed for investors who want the growth potential of stocks, and the cushion [that] bonds may provide.”

Whatever label is attached to Oakmark, it is definitely less risky than a 100 percent stock fund and often features market-beating returns. Although this label is somewhat fudgy as well, Oakmark takes an eclectic approach, meaning it achieves lower risk through novel means. Its bond portfolio, for example, contains several high-yield corporate bonds, the bad boys of the bond world that carry the highest risk in return for almost double-digit yields. Where it counts, Oakmark is ahead of the pack, producing a five-year average return of 16.4 percent a year, handily beating its peer-group (of large-blend funds) average of 13.7 percent. The fund has been in the top 10 percent of its class over the last three- to five-year periods.

On the stock side, Oakmark’s “deep-value” approach keeps McGregor looking for bargains that no other fund would touch. He finds unlikely picks like J. C. Penney, the musty, old-line department store that was a huge winner for the fund, up 90 percent at one point. Unlike the Pax funds, McGregor doesn’t care what a company looks like to other investors; he’s buying for price and income. He holds UST, the holding company of U.S. Tobacco, a leading maker of chewing tobacco, which also pays a healthy dividend.

It’s also not important to McGregor how big a company is in terms of market capitalization or what industry it represents. Like most deep-value managers, it’s the price of a stock—and its capacity to turn around—that interests him. Every value manager makes a bet that they can find a pearl among swine, a gem of a company that the market has underpriced for one reason or another. They are intelligently sneaking around a market maxim that holds that all securities are priced correctly because all the facts about the company are known to the public and market analysts. This is the “efficient market theory.”

Value managers like McGregor are betting they can spot stocks that are flying under the radar of market efficiency, take large stakes in them, and hope that the market will realize—and raise—the market value of the company in question. It’s like finding a Picasso at a garage sale. The best value managers can do this consistently because they have a team of bloodhounds—their analysts—who are constantly looking for companies that are bruised, beaten, and neglected. Once they get the scent, managers like McGregor can pounce. He places his bets on a few companies that he thinks will see double-digit turnarounds once the market turns his (and the company’s, for that matter) way. In the short term, this is a risky strategy if the bets don’t pay off. The risk lessens, however, over several years, since value managers like McGregor are not looking for—or expecting—a quick profit.

Case in point is McGregor’s purchase of J. C. Penney. When most people think of leading retailers, they think of Wal-Mart, Target, Costco, and Amazon.com. Penney, to most people, hails from another era, when department stores meant clothing on the first floor, appliances on the second, and bargains in the basement. It was the world that Sears dominated for decades. It was a formula that worked before deep-discount, specialty, warehouse retailing, and the Internet sold everything that Penney sold—only cheaper and faster. Penney was a dinosaur, and Wall Street was waiting for changing retail tastes to finally put it out of its misery.

Like any astute value manager, McGregor sensed Penney wasn’t getting a fair hearing on Wall Street and listened to what management had to say. “Penney’s CEO lays out a plan to earn $5 a share in 2000 and mentions plans for Eckerd [the nation’s third-largest drug store chain, which Penney bought]. Eckerd had this idea that they wanted to make it convenient for their customers to get in and out in seven minutes, so they put their prescription counters in the front of the store. Then they figured out, like their main competition, Walgreen’s—which has their prescription counter in the back of the store—to move their prescription counters to the back. Sales go up. They cut their dividend to two percent and some year-end tax-loss selling makes the stock even more attractive. We figure they’ve already been through the wringer and it’s hard for them to disappoint investors at $25 a share. Later we sell at $50.”

McGregor’s analysis hinges on value-investing orthodoxy: What is a business really worth and does the stock price reflect its worth or intrinsic value? By adding up all of the company’s assets and subtracting liabilities—that is, finding its book value—value guys like McGregor try to establish a price-to-book ratio (p/b ratio). This is the company’s stock-market price divided by its per-share book value. You don’t need to do the math here, but a p/b ratio of more than 1.0 usually shows that the price of the stock is valued above the total value of the company’s assets. In other words, investors attach a premium to a high p/b ratio company, which means it’s no bargain.

Value investors first determine if a stock is a bargain by looking at the company’s net worth, rather than focusing on earnings growth, which is a secondary concern. Growth-oriented investors, in contrast, first look at price/earnings ratios or p/e ratios. The p/e is calculated by dividing the current stock price by the last twelve months of earnings per share. This ratio tells investors how much the market is willing to pay for a dollar’s worth of profits. The higher the p/e, the greater value the market places on those earnings.

Neither p/b nor p/e ratios tell the whole story of why value players like McGregor can outfox the market at times. Like the constant tug-of-war between stocks and bonds, growth and value are constantly wrestling each other for dominance in the stock (and sometimes) bond markets. When earnings are consistent and upsurging—as they were between 1991 and 1999—growth carries the day and value is out of favor. When earnings across the board fall out of favor, as in bearish markets, value is the more dependable way of making money, which is why funds like Oakmark are worth considering.

Value and Growth: The Road to Risk

A few months after I visited Clyde McGregor, the Wall Street Journal, in headier times “The Diary of the American Dream,” ran a story headlined “NASDAQ Companies Losses Erase 5 Years of Profit.” I’m not quite sure why this piece ran on page C3 instead of on the front page, but its conclusions were shocking. Losses from the top technology companies in the NASDAQ eliminated all of the profits from the stock run-up of the 1990s. In late 2001, the darlings of the info age, the monsters of “ego space,” were in tatters. Intel, Microsoft, Oracle, Dell, and Cisco Systems were still in the black, but JDS Uniphase, VeriSign, and CMGI were laid to waste. JDS Uniphase’s losses alone were $51.6 billion as of 2001. The Internet darling Excite@Home lost $10 billion. These were companies that investors could not buy enough of at the beginning of 2000. The Journal estimated that the collective losses of the NASDAQ leaders chewed up five years’ worth of profits. The all-electronic market was back where it started in 1995.

If earnings disappear, what’s left? Can you make money with companies that produce no profit? Well, for one thing, unprofitability makes a company an unlikely candidate for short-term growth in its market price (in normal times). More important, it makes companies that had earnings all along and were underpriced relative to fad stocks even more valuable. Enter our mattress-loving friends in the value kingdom.

BEAR-BEATERS: STOCKS THAT SOARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 2001 ROUT | ||

Company |

| Increase* |

Northrop Grumman |

| 15.9% |

Lockheed Martin |

| 14.8% |

General Dynamics |

| 9.2% |

Placer Dome |

| 5.7% |

Washington Mutual |

| 5.5% |

Golden Western |

| 5.5% |

Newmont Mining |

| 5.2% |

Barrick Gold |

| 3.5% |

Countrywide Credit |

| 3.1% |

Fannie Mae |

| 2.8% |

*Returns reflect the period from September 10 through September 18. The top three stocks benefited from the perception of increased military spending; Placer Dome, Newmont, and Barrick are gold-mining stocks that spurt in times of worldwide crisis or inflation, but have been awful investments long term; Washington Mutual, Golden Western, Countrywide Credit, and Fannie Mae deal in mortgages. Interest rates dropped after September 11. Source: Reuters and the Wall Street Journal. | ||

Size Matters, Sometimes

Before I outline more of the value school’s philosophy, I need to explain a little more about capitalization, which is not as important to value investors as finding an outright bargain. Knowing a little about capitalization, however, will tell you something about risk. Capitalization, you will recall, is the market price of a stock multiplied by its outstanding shares. With any public company, it’s an easy calculation to make, and generally gives a thumbnail sketch of how much investors value a company. In recent times, sales and profits were used to rank companies in lists like the Fortune 500 and Forbes 400. Now it’s market size that matters.

Market capitalization doesn’t really tell you much about how a company is run, but it does tell you the plurality opinion on how much the market thinks a company is worth. The greatest amount of attention—in the market and the press and among active investors—is paid to the large-capitalization or “big-cap” stocks. These are the GEs and Microsofts of the world. Every drop of perspiration of every major big-cap executive is studied carefully to see which way earnings will go. The big boys account for some 72.5 percent of the dollar value of all stocks listed, according to Ibbotson, so maybe that’s why they garner so much attention.

The next tier—stocks with market caps between approximately $1 billion and $10 billion—are called “mid-cap” stocks. These are lesser-known companies, like National City, which as a whole comprise about 11 percent of the market. The rest of the more than six thousand listed stocks comprise less than 17 percent of the market and fall into vaguely defined categories called “small-caps” or “micro-caps.” A loose definition of a small cap is any company with a market capitalization of $1 billion or below, but there are always arguments in the industry as to where the line should be drawn.

Market cap is important to value managers because the lower you get on the market-cap totem pole, the lower the likelihood that Wall Street is paying attention—and the greater chance of finding unique information about a company and plucking a bargain. I don’t think any one hundred Americans could easily name a single mid- or small-cap stock, while most of us can easily come up with big caps like General Motors, Procter & Gamble, and Coca-Cola.

Mid- and small-sized companies don’t always move in the shadow of the big boys. They may tag along because they are just getting started, not well known to the investing public, and have lower profiles, so not as many Wall Street analysts or mutual-fund managers follow them. Ultimately, that means that there’s less of an onus on the mid and small caps to post consistently higher earnings. The Street isn’t hanging on to every hint of an earnings “surprise,” so they tend to be less volatile.

Capitalization also comes into play because smaller companies tend to be more nimble; they can move in and out of businesses more efficiently, they need less capital to grow their enterprises, and their mistakes are less publicized. So they tend to have much more promising upsides and their downsides are not as steep as their big-cap brothers. And that’s why value managers often gravitate to the mid and small caps when the big boys are overpriced or are just not performing well. Managers like McGregor stick with big caps, although capitalization is less important than the price and appreciation potential of the company.

Capitalization plus Style a Better Guide to Performance

Being a value investor means taking lower risk, but you can enhance your returns in down markets by also looking at the capitalization of the companies in your portfolio. Since value investors are more concerned with the long-term worth of a company, in the short term they are not obsessed with returns and can be more patient in waiting for smaller-cap companies to produce earnings. Looking at historical returns of investments is always a dangerous business anyway. It’s misleading to think that performance over a long period of time will tell you anything about the present or future.

Although long-term small-cap stocks outperform large caps as a class, there’s much more to the story. Investment style also enters into the picture. Use real estate as an example. Let’s say there are two investors, Joe and Jerry. Joe buys all of his real estate at a 30 percent discount to listed price. He insists on that discount or he doesn’t buy the property. Jerry, on the other hand, believes the properties he buys are all fairly and efficiently priced and he is even willing to pay a premium, because he knows appreciation is virtually guaranteed. Which investor comes out ahead in the long run? By picking up bargains, Joe is looking at better profit margins than Jerry, all other things being equal. As the table below shows, when the bear market hit in March of 2001, small and bargain-priced stocks did the best, while small, overpriced stocks got hit the worst.

HOW VALUE INVESTORS FARED BY STYLE IN THE EARLY BEAR MARKET | ||

Capitalization/Style |

| Return* |

Large value |

| 9% |

Mid-cap value |

| 28% |

Small-cap value |

| 20% |

Large growth |

| −33% |

Mid-cap growth |

| −45% |

Small growth |

| −46% |

*Returns from 2/28/00 to 3/31/01. Source: Kanon Bloch Carré, www.kanon.com. | ||

It pays to shop for bargains when times are tough. Investors who buy stocks (or bonds, for that matter) at a discount to market value do better over time than those who pay the going rate for a security. This idea not only sounds appealing, but is backed up by a solid body of academic research. In a famous 1993 paper entitled “Contrarian Investment, Extrapolation and Risk,” Professors Josef Lakonishok, Andre Shleifer, and Robert Vishny found that “value” stocks purchased at a discount outperform stocks that are more highly valued over time.

The hidden gem in the “contrarian” strategy is that value stocks also did well during the stock market’s worst twenty-five months from April 30, 1968, through April 20, 1990 (the period of the study). Having a basket of low-priced stocks, you can conclude from the study, is more profitable than buying stocks “at retail.” The cherry picking of cheap stocks also implies that you need to ignore the companies that the market values most highly—those stocks with sterling earnings reports. Value managers like McGregor look beyond the few warts on the frog to find the inner prince.

Like Graham and Buffett, Phil Fisher also believed that superior companies are often overlooked. These companies have bad years, but over the decades they prevail. As Robert G. Hagstrom Jr. said of Fisher, “The characteristic of a business that most impressed Fisher was a company’s ability to grow sales and profits over the years at rates greater than the industry average.”

One of the best value fund managers of all time, John Templeton, was a staunch value investor. His Templeton Growth Fund was the best-performing mutual fund from 1964 to 1994. Although Templeton has since retired from managing money, his techniques are shared by a whole group of managers who now follow Warren Buffett’s every move. Templeton, who employed value techniques on stocks all over the world, did well because he was often a contrarian, buying inexpensive stocks that were out of favor. McGregor followed the same path in buying J. C. Penney and a host of other neglected companies.

As Templeton’s record and subsequent studies proved, the value technique works in finding winners in the United States as well as abroad. A 1991 Morgan Stanley study of 2,349 companies found that the bargain approach even worked with a “world” portfolio of 80 percent non-U.S. companies. The average return of the value stocks from 1981 to 1990 was compared to the benchmark Morgan Stanley Capital International global equity index. If you had $1 million to invest in these low-priced stocks starting in 1981, it would have increased to $7,953,000 at the end of 1991, compared to $3,651,000 from more expensively priced stocks. Price does matter to the value camp and it’s more profitable over time.

What about periods in which the core of the U.S. stock market is getting sold off? Let’s assume the thrill is gone and investors are heading for the exits on all of the big-cap stocks. In this case, the value approach still holds up. In a study by Kanon Bloch Carré, they found that large value outperformed large-growth stocks by 42 percentage points in the last thirteen months of the bull market that ultimately ended (by their definition) on March 31, 2001. Style matters if you’re in a pinch.

To find an even fluffier cushion when the market gets rocked, a fund that combines a value approach with bonds and income-paying stocks is a good investment. You probably won’t outperform the market with an equity-income fund in good times, but you will have some padding if things turn nasty. Keep in mind that the best-managed companies over the long run have relatively low debt, own shares in their own company, are not capital intensive, are not subject to extensive government regulation, are reducing costs constantly, and are often out of favor, according to portfolio manager Charles Brandes. Of course, these are just starting points for a whole course on value investing, which I will cover in greater detail in the next chapter.

Where You Find Balance

To understand the ultrarational world of value investing, you need to take a walk in what Warren Buffett calls “Graham and Doddsville.” That means studying the Rosetta stone of value investing, Graham and Dodd’s Security Analysis, the 1934 classic. This is Benjamin Graham’s legacy and the starting point for any aspiring value investor. Although you may find most of this tome impenetrable, I found one section that resounds with clarity and purpose:

The common goal of all investors is to acquire assets that are at least fairly priced and preferably underpriced. Should such assets become overvalued, the investors’ goal is to recognize the fact and dispose of them. Since this valuation relates to unknown future events, its accuracy may depend as much on the economic, capital market, sector and industry factors at work as on specific company performance.

The proof, for value investors, is in the “fairness” of the pricing (read “priced cheaply relative to the competition”), which they hope leads to performance in lean times as well as fat times. Everything else is a “top-down” consideration, that is, a focus on external events like economic reports, stock market averages, and whether an industry is in or out of favor.

There is a familiar fable that describes investment philosophies indirectly: “The Princess and the Pea.” Remember the Hans Christian Andersen tale of the would-be princess who is tested by a prince, who is unsure she is a real princess? He stacks twenty mattresses on top of a hidden pea and asks the lass to spend the night on the huge bed. In the morning, she complains of a stiff back because she felt the pea, and only a princess could have such a delicate frame. (If she hadn’t felt the pea, she would have been one of the rabble.) In growth investing, the pea is earnings. Without earnings, you have no princesses, and certainly no growth. In value investing, forget about the pea, because you have lots of mattresses. Who cares if the princess is comfortable or not, or even if she’s royalty? She can sleep in the Budgetel for all we care.

Value investors like to think that they know that there are several princesses on top of all of those mattresses in the market. It just takes some skill and experience to find them, which you can do, too, if you follow their philosophy with conviction (or just invest in their mutual funds).