CHAPTER 5

Growth plus Value: How to Outsmart the Market

Of the various ways of making money in securities, I know no better way than through a close watch on management. Changes I particularly refer to are those where companies have been in difficulty, their stocks depressed, and general dissatisfaction expressed—and where a new management comes in and invariably begins by sweeping out the accounting cobwebs.… Thus an investor at this juncture often gets in at the bottom or the beginning of a new cycle.”

—Gerald Loeb

Being a mutual fund manager is a bit like being a wildcat oil driller. You mostly hit dry patches and try to drill where the other guys aren’t. When you hit a patch of Texas gold, then you’re in business and everyone knows it. In the abstract world of money management, fund managers hit more dry patches than gushers. When they hit petroleum, it makes their year, creating heroes in a world so competitive that everyone takes notice and most fail. To find their fortune, they all read the same sacred texts by Benjamin Graham, Philip Fisher, Philip Carret, and Warren Buffett. They calculate the same equations and talk to the same companies. While focused on not losing their clients’ money, they try to make a few bets that carry as little downside as they can get. Value managers tend to scour the Permian basin of forgotten, neglected, and unseen companies. They probe balance sheets, talk to customers, drill CEOs. They are constantly seeking a piece of information that will confer upon them the market’s blessing: a hidden fact about a profitable business, an undervalued asset, a turnaround strategy from the new guy at the head of the conference table. One bad guess is excusable; even a bad year is okay. Two bad years and they are told to leave a trail of dust.

Bill Miller hasn’t seen a bad year since Saddam Hussein was chased out of Kuwait City more than a decade ago. Although his Legg Mason Value Trust fund lost 6.2 percent in 2000 when the S&P 500 lost 9 percent, he’s still scoring where it counts—he beat the S&P benchmark average for the tenth consecutive year. No active fund manager can make that claim, which puts him in a league with Buffett and Lynch in the pantheon of money runners. In a world in which beating the S&P just two years in a row is a near-Herculean feat, Miller doesn’t have a “master-of-the-universe” kind of attitude. He is as taciturn as a tax preparer and as precise as a neurosurgeon (what he does is often more complicated than brain surgery).

Miller’s mind is coiled, ready to pounce. For a man who has been more successful than any of his contemporaries, his heroes are people like William James, the philosopher and psychologist. Like James, Miller explores every quantum bit of knowledge he can find before he makes a decision. Seeking the esthetic of hidden profit, Miller is an archaeologist of the unknown material fact, the tightly wound packet of energy that will send a stock from the black hole of market obscurity to the stellar recognition of a stock the Street wants to own.

Starting in finance as a treasurer for a supplier to steel and cement products companies, Miller didn’t come from the right places to do what he’s doing. After graduating with honors from Washington and Lee University in 1972, he went overseas as a military intelligence officer. He pursued his doctorate in philosophy at Johns Hopkins, went to J. E. Baker Company as treasurer, and started as a fund analyst at Legg Mason in Baltimore in 1981. Now he’s managing $25 billion, but he’s as circumspect as a graduate student before a dissertation defense.

Miller’s humility is like an aura. He doesn’t swagger and openly discusses how he achieves his results. With the discipline of a drill sergeant, the quantitative mind of a physicist, and the daring of a stock-car driver, he races into his method for finding bargain stocks. He goes against the grain a lot of the time. Some of his favorites include Eastman Kodak, Amazon.com, and AOL Time Warner. While these stocks may look sour in the short term, Miller doesn’t care. He’ll wait a few years to see his stocks rise to the occasion.

“There’s no off-season for me,” Miller begins. “I invest in companies for a three- to ten-year life span, so that lowers the risk of my portfolio. Risk is calibrated to time horizon.”

Paraphrasing Buffett’s dictum not to lose money, Miller launches into his controversial decision to buy AOL (now AOL Time Warner) in the fall of 1996 when nobody wanted it and AOL subscribers could barely access the Internet through the on-line service. His purchase was anathema to most of the value orthodoxy: he was buying a high-profile growth company in the technology sector. Only the hot-shot sector-fund guys did that. Value guys bought companies nobody heard of, in places where the Wall Street suits wouldn’t soil their Guccis. AOL had been trumpeted on CNBC multiple times, for God’s sake. Nevertheless, Miller doesn’t think like most fund managers. Growth is actually okay to him, as long as he can get it for a song, a sweet little ditty at that.

At the time of Miller’s purchase, AOL’s price had collapsed from the 70s to the 20s. It had gone from info age wunderkind to an incompetent, snot-nosed Internet service geek. The Street thought the company was toast because its millions of subscribers had a rough time getting onto the World Wide Web, which was its raison d’être.

“Despite significant log-on problems, AOL’s existing customers weren’t switching to the Microsoft Network or Compuserve, and its customer base actually continued to grow. When we analyzed traffic patterns of customers using the services, we found one reason why. AOL customers spent eighty percent of their time using its proprietary service rather than the Internet, while customers of the Microsoft Network spent only twenty percent on the proprietary service. The AOL value proposition [the content AOL offered] was clearly very powerful. But we knew people wouldn’t stay with AOL if they couldn’t log on. So we analyzed how long it would take AOL to solve this problem. Our analysis suggested that AOL could deploy the fix quickly enough and had sufficient capital to do so.”

Miller held on to AOL and made huge profits—thirty to forty times the original investment—when the service figured out how to smooth out its Internet connections (only to see it drop 54 percent in value last year). Then Miller further piqued his critics by buying Amazon.com. Like all good value managers, he got into the minds of the executives of the company he owned, saw how they ran their business, discovered how they could work out their problems, and held on while they executed their solution.

His technique was to use the wisdom from all of his predecessors and contemporaries: Peter Lynch, Warren Buffett, John Neff, Mario Gabelli, Chris Davis, and Mason Hawkins. All have fairly secure places in the “value hall of fame,” but only Lynch, Buffett, and Neff have made it outside the inner sanctum of the most serious investors.

Miller cites a phrase used by the legendary value investor John Templeton to describe when he knows a stock may be ripe for the picking. “I look at when there are extremes of emotion, or as Templeton said, the ‘point of maximum pessimism.’” That meant loading up on AOL and Amazon.com when the Wall Street consensus was that the companies were history. That meant getting into the heads of the managers of those companies to see how they would (and could) work things out. Like Buffett, he concentrates on the unique nature of the franchise he is buying. He’s not buying a stock, he’s buying the human element of management and its ability to change and transform a losing situation into a winning one.

“I look at the franchise and the history of the business. I look at their industry, the market for their products and if they can sustain the return on capital. I look at the central tendency of valuation.”

Now Miller is talking his own, highly refined dialect. His process looks at whether the company he is prospecting is inexpensive relative to its intrinsic value.

We project cash flows under a variety of scenarios. Each scenario gives us a different value and then we see how those numbers cluster. If they cluster around the same range, then we have a pretty high confidence in that range. Then I talk to management and see whether they can motivate people, if they are making quality products, if they have customer loyalty, common sense, and good relations with the government and employees. Is it a quality company run by quality people?

Miller is, by all accounts, an ace at judging whether a company’s management can turn around a bad situation, but he can be wrong, such as the time when he bought computer maker Gateway, another untraditional pick for a value manager.

Even more surprising about Miller is that, despite his reputation as a value manager, he says he “rejects the distinction between growth and value. Growth is an input into the value equation. We are driven by where the best values are.”

There’s a reason why Miller is on the board of directors of the Santa Fe Institute, where the top minds of the world gather to discuss the cerebral pastiche of nonlinear systems, complexity, and chaos theories. His deep-thinking value approach to growth extends to old-line companies like Kodak and new economy companies like Nokia. He bought Nokia in 1995, for example, when the business was dominated by #1 Motorola and #2 Ericsson. Now Nokia is the cell phone market leader with about a third of the market. He’s been guessing right for a long time, having doubled money from a high-school summer job by investing it in RCA in 1965 through 1966.

But Miller also ascribes to the value school’s orthodoxy: Own a business at a discount; invest rather than trade; buy a business that earns a return higher than its cost of capital (the expenses it incurs to run the company). Miller’s approach is not for the weak of heart. Among value managers, he’s not known for taking the safe road. His level of analysis is intensive even for a value manager, but his big bets could blow up or simply not produce the results he expects. After all, no amount of research will tell him which way the business cycle or economy is headed—which value managers say isn’t relevant (at least that’s what they tell their shareholders). Miller’s style also defies easy categorization because he combines the growth and value schools so well. Morningstar vaguely defined his style (for the flagship Value Trust Fund) as “large-cap blend,” which doesn’t tell the story.

Although Miller thinks the S&P will grow in the 6 percent to 8 percent range in coming years (echoing the age of diminished expectations), he turns whimsical when he reflects on his success. “You know how to beat Tiger Woods? Don’t play him at golf. You need a competitive advantage or don’t compete.” And one more wager from the man you wouldn’t want to bet against when it comes to the stock market: He thinks Bill Gross’s prediction that stocks won’t go much higher than a 5 percent annual rate of return is wrong.

Value in a Nutshell: How You Can Find It

To say that the value style of investing is the most successful way to mine the canyons of the stock market is like saying that all you need is a submarine to explore the entire ocean. It’s rarely that simple and gets complicated when you explore the details of what the Bill Millers and Warren Buffetts of the world are talking about. You can, of course, save yourself a lot of time and mental exertion by simply buying their funds. You might find Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway a little pricey—and it’s like a mutual fund, it’s a company that owns other companies outright (but doesn’t run them), like Geico Insurance, and large stakes in others, like the Washington Post Company. As I write this in late 2001, Berkshire Hathaway is trading at $68,000 a share. The Oracle of Omaha (Buffett’s moniker) doesn’t believe in stock splits. If you want some quality, affordable value mutual funds, skip to the end of this chapter. If you want to know how they evaluate companies, read on.

I want to point out a few salient points, however, about why value investing is such a potent style over time. Value stresses holding stocks for the long term, which, in the short attention span of Wall Street, is often one year. Buffett, in contrast, stresses that his holding period is “forever,” although he admits to mistakes now and again. (U.S. Airways is a case in point.) Holding stocks reduces the chance of missing a business cycle or stock rebound because the manager steps away from a hunch that the stock should be trading higher. That translates to less volatility in down markets.

Value investing is also about, in the parlance of baseball, “hitting them where they ain’t.” Value managers are famous for their belief that most of the market is wrongheaded about particular companies that have hidden virtues that only they can see. “An entire school of investing is based on the premise that over short periods the market is often misguided but over the long run true value will win out,” note Gary Belsky and Thomas Gilovich in Why Smart People Make Big Money Mistakes (Simon & Schuster, 1998), an informative study of investor psychology. Yes, value investors have a conceit that they know something you don’t about companies that are likely to rise in value. No, they are not always right, but when they are, they do very well because they have bought companies that typically have little downside.

More important, it is a fairly solid fact that value investing is far more profitable. When you average all value stocks (large and small), you get an average return of 16.6 percent since 1928, according to Ibbotson, versus 11.7 percent for all growth stocks. Like most of the market, value goes up and down in cycles. When growth is in favor, value is not (see the chart). But over time, value wins out.

While a 5 percent difference rate of return favoring growth doesn’t sound like much, over twenty or thirty years the difference in the amount of money you would compound is striking. Here’s what compounded returns look like at some various rates of return. (Note: This shows only a 3 percent difference.)

VIVE LA DIFFERENCE: VALUE’S ADVANTAGE | ||

$10,000 Invested at … |

|

|

Taxable Account |

| Tax-Deferred Account |

19% for 30 years= $171,743 |

| $760,838 |

19% for 20 years= $ 66,566 |

| $179,554 |

19% for 10 years= $ 25,800 |

| $ 42,374 |

16% for 30 years= $102,820 |

| $353,690 |

16% for 20 years= $ 47,285 |

| $107,750 |

16% for 10 years= $ 21,825 |

| $ 32,825 |

Source: www.cuna.org. | ||

The 1990s a Fluke for Growth?

It’s possible to make the argument that the 1990s growth boom was an anomaly. Maybe some economic historian will look back on the 1990s and conclude that a combination of falling interest rates, falling trade barriers, more productive business, and baby boomers chasing big-return stocks was a onetime event that made growth investing so popular. After all, with computers and information technology, large businesses were able to dramatically reduce their labor and operations costs. Trade tariffs and other barriers went away thanks to the North American Free Trade Agreement and the World Trade Organization. And 77 million investors were anxious to save for their retirements, so they chased any positive earnings report or growth-oriented mutual funds they could find. A unique moment in history? Perhaps. Maybe there’s another decade or two left to this scenario before the growth party is over. No predictions here.

Or maybe the growth parade really was a fluke and productivity, globalism, and baby boomers have reached a plateau in the grand scheme of things. If you examine every decade going back to the 1920s, the only time growth beat value as a style of investing (other than in the ’90s) was in the 1930s, when the bottom kept falling for stocks and there was nothing but growth from the depths of the Depression.

Once again, a dollars-and-cents comparison is in order. From 1927 to 2000, if you had that mythical breadbasket of all large-growth stocks starting with $100, you’d have $932,130 at the end of 2000. With the same amount invested at the same time in all value stocks, you’d have $7,755,390 at the end of the same period.

Value Isn’t Always Valuable

Before you get too excited and dump your entire portfolio into value funds, we need to stop for a minute. As you can see, there are times when value investing languishes. It doesn’t work all the time, as any value investor can tell you if they had most of their money in value stocks during the 1990s. It may well be that value works worst in a cautious or turbulent market.

The 1930s and 1990s were highly deflationary and ultimately led into more prosperous times. Remember that the 1980s started out with double-digit inflation and interest rates and by the end of the century inflation was running under 3 percent. That’s pretty bullish for producing earnings that are not saddled with high costs of doing business. Value reigns supreme when the business cycle is heading south. That’s a fairly safe assumption. If profits are going to be lagging due to a slack economy, value is a safer place to be than growth. The downside is not as steep.

My observation is reinforced by research conducted by John Bajkowski of the American Association of Individual Investors, who in researching all of the major styles of investing in the 2000 bear market found: “As a general rule of thumb, approaches that focus on value tend to have less portfolio turnover [buying and selling of stocks] than pure growth approaches, tend to be less volatile, and outperform other approaches during bear markets.”

How Does Value Work: The Nuts and Bolts

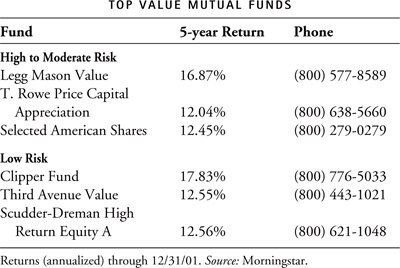

The language of value investing is quantity and quality. The quality side was summarized by Bill Miller fairly well, and he articulates what nearly every value investor looks for when vetting the management of a company. On the quantity side, there’s a little math involved, so if you’re satisfied you’ve learned enough about value investing, skip to the end of the chapter to see my picks for the best value mutual funds.

Value investors are sticklers for details that most investors won’t take the time to divine. They are looking for insights on how a company that’s underpriced, relative to the market, may become more attractive to the rest of the market. They do this by examining:

• Price/earnings ratio. As we mentioned, this percentage is determined by dividing the current stock price by the trailing twelve-month earnings per share. This earnings “multiple” tells investors how much the market values a dollar of earnings. If a stock’s p/e is 40, it’s trading at forty times earnings. This is a number that should be compared to the average p/e of the industry the stock represents. A low p/e is more attractive to value investors than a high one, particularly one that is below an industry average. Value investors shunned nearly all of the technology stocks of the bull market because of sky-high p/e’s, including some as high as 200.

• Price/book ratio. The market price of a stock divided by its per-share book value. The book value is to value investors what the bull is to the matador. They zero in on book values because they represent the value of the company’s tangible assets. That means accounting for all of the company’s operations and assigning a dollar value to it. A p/b ratio under 1.00 means that the price of the stock may not reflect the value of those assets, signaling a possible bargain. The p/b ratio, however, doesn’t address the nontangible assets such as franchise value, patents, or trademarks.

• Sales growth. Not as important as earnings, but a factor that drives profits. Typically, a company with improving sales growth will boost earnings. In legendary value investor John Neff’s view, rising earnings must be supported by rising sales to make the company more appealing.

• Free cash flow. This is the amount of money a company has left over once it has paid for capital expenditures. It’s preferable to investors for this money to go back into the company to buy equipment or grow its business, pay dividends, or buy back stock, which boosts the stock price.

• Operating margin. This is profit that the company uses to run the business. It needs to be compared to similar businesses and its respective industry. Is the company as profitable as the competition? Are its operating margins going up or down?

• High dividend yields. This has been a fairly consistent starting point for investors for decades and not just for value players. Companies with low p/e’s (and stock prices) often have high dividend yields, a percentage of dividends based on their current stock price. Dividends serve as a buffer against stock prices falling. Even if the stock price tanks, you still have that dividend coming in every quarter, so you have some protection on the downside. Many investors have structured entire portfolios based on dividend-rich companies (see chapter 9), but dividends are only part of the story. Dividends are usually an indication that a company is profitable and willing to share a percentage of its earnings with investors. But they tell no tale about the quality of management.

• Return on equity (ROE). Of all of the measures used by value investors, this figure is the most elusive and most misunderstood. Fundamentally, this is a ratio that shows how shareholders have benefited by management’s investments in the company: profit divided by shareholder equity at the end of the year divided by equity at the beginning of the year divided by 2. In an example offered by the American Association of Individual Investors (AAII), if a company earned $10 million, started the year with $10 million in equity, and finished with $30 million in equity, its ROE would be 40 percent (shareholder’s equity is the company’s assets minus liabilities, “net worth” to personal investors). If a company produces a higher-than (industry)-average ROE, it’s not only growing the business, it’s building shareholder wealth as well. ROE is Warren Buffett’s most publicized way of tracking consistent managers over the long run; companies need to be able to sustain high ROE to make his grade.

Summing Up the Value Approach

I can’t presume to do the value approach justice in a few pages. If you are interested in picking stocks using a value regimen, I recommend a number of texts on the subject in the Resources section at the end of this book. There are dozens of other facets to this thoroughly intellectual process.

In studying value investors, you will find that they are inordinately patient and wait for the market to restore their companies to what they believe is a “fair” value. They are the defenders of the downtrodden, but only in the sense that their research is designed to make them profit by the market’s lack of vision. Here are a few funds that have vision in spades:

COMPANIES THAT PRODUCED RETURN ON EQUITY GREATER THAN 15% (1989–1999) | ||

Company |

| ROE (Average) |

Coca-Cola |

| 45.6% |

American Express |

| 18.2% |

Gillette |

| 34.8% |

Freddie Mac |

| 18.7% |

Wells Fargo |

| 17.6% |

Walt Disney |

| 16.0% |

Washington Post |

| 15.8% |

Not coincidentally, these stocks are all long-term holdings of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. Source: Timothy Vick, AAII. | ||

Value and Patience

I trust that Miller and his cadre of value investors would agree that his school of investing isn’t for everyone because it involves a degree of examination, insight, philosophy, and patience that many investors don’t have—or don’t wish to acquire. It’s a combination of these factors—plus a bit of luck—that makes value investing thrive. It’s a philosophy built on balance and hope. That reminds me of a passage in Plato’s Republic written more than twenty-three hundred years ago that still rings true. Socrates is conversing with Adeimantus about money and the discussion leads into the relationship between money and virtue:

SOCRATES:… And then one, seeing another grow rich, seeks to rival him, and thus the great mass of the citizens become lovers of money.

ADEIMANTUS: Likely enough.

S: And so they grow richer and richer, and the more they think of making a fortune the less they think of virtue; for when riches and virtue are placed together in the scales of the balance, the one always rises as the other falls.

A: True.

S: And in proportion, as riches and rich men are honored in the state, virtue and the virtuous are dishonored.

A: Clearly.

S: And what is cultivated, and that which has no honor is neglected.

A: That is obvious.

S: And so at last, instead of loving contention and glory, men become lovers of trade and money; they honor and look up to the rich man, and they make a ruler of him, and dishonor the poor man.

A: They do so.

Socrates goes on to talk about the connection between money and citizenship (he could easily be talking about U.S. campaign financing), but his larger point is that virtue needn’t be discarded in a materialistic age. You can be a patient investor and do quite well. After all, patience is a virtue, and it’s often rewarded in value investing. Value investing is about finding hidden virtues in a stock—although there are other approaches to consider that flow from the value philosophy.