CHAPTER 7

Values Abroad: And You Thought the Best Investments Were in the United States?

The old thought that one cannot be rich except at the expense of his neighbor, must pass away. True prosperity adds to the richness of the whole world, such as that of the man who makes two trees grow where only one grew before. The parasitical belief in prosperity as coming by the sacrifices of others has no place in the mind that thinks true. “My benefit is your benefit, your success is my success,” should be the basis of all our wealth.

Anne Rix Militz

Leah Joy Zell is the kind of person who would succeed running a megacorporation, chairing a history department at an Ivy League college, or holding a Cabinet post. Her intelligence and confident élan radiate from her like a high-tension electrical line. In her role as manager of the Liberty Acorn International Fund, she has the job of finding ways to invest more than $2 billion across the world in small- and mid-cap companies. Like John Rogers and Bill Miller, she is largely a value player, but she focuses on overseas companies that have market capitalizations under $5 billion. She spends most of her time traveling between the countries where she has the top-five allocations: the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Japan, Germany, and Canada. She has more frequent-flyer miles than time to spend them.

Taut with short hair and wire-rimmed glasses, Leah Zell takes her time to compose her sentences as if every one of them is to be written out in elegant prose. With continents to consider, she does the mental calculus of finding bargains across different economies, reading prospectuses in different languages, diversifying across several industries, and dealing with the fluctuations of several currencies. Holding a Ph.D. from Harvard in modern European social and economic history, she’s an unabashed expert on how Europe and Japan rebuilt after World War II. With that unique perspective, she knows the landscape with an academic, disciplined sense of history. Although she is brimming with investment ideas, Zell doesn’t have to go far to discuss investing. Her husband and partner, Ralph Wanger, is the revered manager of the Liberty Acorn Fund, a small-cap domestic fund. Her brother, Sam Zell, is the legendary real estate mogul also known as “the grave dancer” for his prowess in finding properties at fire-sale prices.

Balance is a powerful theme in Zell’s work. Her Harvard dissertation concentrated on finding a workable balance of economic growth and stability in the postwar era. As a value investor, she is constantly seeking the ideal medium between price and the intrinsic value of a company. Due to the objective of her fund, she has to look for that delicate combination outside the sphere of powerful international companies like Nestlé, Philips, Daimler, and Nokia. Instead, she focuses her research on lesser-known companies like the Serco Group, Li & Fung, Autogrill, and Capita Group. Her fund contains no more than 20 percent of its holdings in any one industry; it’s diversified across business services, consumer goods/services, financial services, broadcasting/media, and industrials.

“I look for stable yet dynamic companies. I have an intuitive sense of what’s stable. If a company isn’t satisfying a real demand at a reasonable price, imbalances will always right themselves,” she notes, referring to the market’s propensity to reward investors who are buying financially sound companies at a good price.

Zell is thriving relative to her competition and foreign stock funds in general. It hasn’t been easy for any international fund in recent years, either. Economic turmoil has continued not only in Japan for the eleventh straight year, Southeast Asia has been hit hard, along with South America (particularly Argentina) and Russia. Although she sticks with the countries with the most durable economies, returns for international funds have been paltry relative to the booming returns seen on Wall Street. The index to which she compares her fund’s performance—the SSB EMI (Global ex-US) Index—has shown a negative 0.39 percent return over the past five years and a loss of more than 2 percent over the last three years. A piggy bank shows a better return. Zell’s fund, however, has returned 9.98 percent over the past five years and 13.44 percent over the last decade, trouncing the index average. Those returns are remarkable given the fact that 8.5 percent of her fund is in Japan and Europe, which didn’t post the same stellar returns as the United States during the 1990s. She attributes her performance to the same reason the tortoise beat the hare.

“We build our investing strategy around patience,” she says with her wry smile. “The media wants us to be in the right asset class all of the time, but my job is to invest in small-cap equities all of the time.”

Zell likens her research mission to “history turned inside out.” History has ready information that needs to be interpreted. Analyzing a stock requires starting with a story or a hypothesis on where the company is going and filling in the gaps. Managers call the story “themes,” which are leitmotifs in a company’s ascent to market recognition. For example, she has explored the theme of corporate outsourcing, a situation in which a company decides not to pursue a line of business on its own and contracts it out to another company, usually because the service or product can be provided at a lower cost. Zell then bought a few companies that performed contract manufacturing as a play upon that theme. These companies had decent profits and ran at 100 percent capacity, so the economics were compelling. Then she sold those holdings as they became overpriced (in terms of p/e ratios).

“Does the theme have ‘legs’? Is the concept valid? That’s what we ask ourselves.” Zell also walks her analysts through the standard retinue of the value gauntlet: “What is the quality of the management? How is the business franchise? Does the company have a good balance sheet? I don’t like balance sheet risk [high debt levels relative to equity, the debt to equity ratio].”

Zell reduces portfolio risk by having not more than 8 percent of her portfolio in any one stock and diversifying across countries, regions, and industries. After the fund lost a fifth of its value in 2000, she sold off half of her technology holdings and boosted exposure to more stable sectors such as health care, financials, and energy. Although short-term, the firm takes an average amount of risk; it’s had slack years in the mid-’90s and a Katie-bar-the-door year in 1999, when it rocketed 79 percent. Because of its high volatility—its standard deviation is 27 percent—you can’t jump in and out of this fund. It’s like going to London or Paris for an afternoon. You spend more time on the plane and getting fogged by jet lag than you do on the Champs-Elysée. Nevertheless, despite the volatility, a steady holding in this fund over a three- to five-year period will probably see you outperform 75 percent of her competition.

With her characteristic confidence, she comes off a losing year with an eye on history, which tends to be in her favor. “International small caps outperform large caps over time. It’s a shame to sell small companies in the middle of their growth trajectory. It’s time to recycle dollars into less well-known companies. I believe in riding winners.”

Small and Mid Caps across the Ocean: Growth on the Other Side of the Big Pond

Most investors are so fixated on Wall Street, they have no idea what lies beyond the Big Board at Broad and Wall. The United States is no longer the juggernaut in manufacturing and services it was; the rest of the world has caught up. Manufacturing has left our shores for places like the People’s Republic of China and Brazil. Heavy manufacturing (vehicles, machine tools, steel, etc.) has taken the biggest one-way ticket to foreign shores. The shift has been so dramatic that the U.S. share of the world’s gross domestic product—the total output of all goods and services—dropped to 40 percent in 2000, down from more than 50 percent in 1970. As a result, foreign stock markets now represent 49 percent of the world’s $19 trillion in stock capitalization, up from a 34 percent share in 1970.

Even more surprising is the diversification of the economies outside of the United States. Although most services are still based here, manufacturing has seen a startling shift to overseas factories. Here’s a sampling:

MAJOR INDUSTRIES NOW OVERSEAS

• 9 of the 10 largest appliance manufacturers (only Whirlpool is based in the United States)

• 8 of the 10 largest metals companies (more steel is made abroad now)

• 7 of the 10 largest vehicle manufacturers (good-bye “Big Three”)

• 7 of the 10 largest electronics companies (no more VCRs or TVs made in the United States)

• 5 of the 10 largest telecommunications companies (look at your cell phone)

Source: MSCI, RIMES Technologies, T. Rowe Price, January 30, 2001.

Following the cyclical nature of markets, foreign stock markets have their day in the sun, but not in recent years. Foreign markets have handily outperformed the U.S. market in years in which domestic growth wasn’t as strong as it was in the late 1990s. In fact, the curve that shows foreign markets outperforming U.S. markets during sluggish times at home is one of the most compelling reasons to add foreign stocks to your portfolio. The zigzag curve of foreign-to-U.S. performance is a billboard for diversification and lowering portfolio risk.

From 1981 through 1994, for example, foreign stocks as measured by the Morgan Stanley EAFE (Europe, Australia, Far East) Index soundly outperformed the U.S. market, as measured by the S&P 500 in ten-year rolling periods. The Morgan Stanley index lumps in economies as dour as Japan with solid performers like Switzerland, so what you’re getting is a broad average.

You need to look at when those foreign markets were doing well to get an idea why it’s good to be in foreign stocks. The EAFE index outperformed U.S stocks in the early and mid-’70s when stocks were dismal investments in the United States, during periods of the mid-’80s (and after the 1987 crash), and in a brief spurt in 1992–1993. In terms of correlation—the statistic that tells you how often two numbers move in the same direction—only Canada had a high degree of correlation between 1970 and 2000 (72 percent). The Pacific region moves with the U.S. market about 37 percent of the time, Europe about 58 percent of the time. Overall, the EAFE breadbasket of foreign stocks travels down the same road as the United States slightly more than half of the time.

In the sensible scheme of diversification, it’s ideal to be seeing some returns overseas when things are not so good here. Globalization has caused more of our markets to follow the path of overseas markets, but some inverse correlation (moves in the opposite direction) is always a solid way to reduce the overall risk of your portfolio.

Risks of Overseas Investing

The diversification from foreign stocks comes with a little price tag. You’ll encounter two unique forms of risk that you don’t have investing in U.S. stocks: currency risk and political risk. Foreign stocks are denominated in the currencies of the countries of origin. Most European stocks, however, are denominated in the euro, a pan-European currency that follows the dollar fairly closely. Like all currencies, the euro is subject to daily changes in value. More than $1 trillion goes through currency markets every business day. Banks buy and sell currencies and futures contracts designed to lock in values on those currencies. Investors speculate or hedge on currencies depending on whether they think—or hope—they’ll go up or down in a short period of time.

For example, if you’re a big institutional money manager, you can buy shares in Daimler, the huge German vehicle company that owns Chrysler and Mercedes-Benz. You buy those shares in euros and you don’t want the euros to fall in value relative to the U.S. dollar. So you either take the chance that the currency doesn’t get hurt, or you “hedge” by buying futures contracts that lock in a certain price level of the euro, which ensures that you don’t lose money on the currency if it falls. The currency fluctuation adds a complex level of risk to foreign investments because the currency markets are as unpredictable as the stock market and are pegged to interest rates throughout the world. So you could make money in a foreign stock, but lose money on the currency “translation” into U.S. dollars. Since there’s no way to avoid this risk, you have to pick a fund manager who’s not too concentrated in one country or region.

That brings us to the subject of political risk. The stability of a country’s economy largely depends on the people running the government and finance sector, namely the central banks. All of the largest industrial economies have fairly strong central governments and banks. Once you get beyond Japan, Germany, Canada, Great Britain, France, Holland, Italy, the Scandinavian countries, and Spain, you enter a world in which huge currency devaluations and inflation are a constant source of economic torment. South American economies are consistently battling inflation, which ravages the industries that do business there. Indonesia and countries doing business with it are still hurting from a free fall in their currency a few years ago. And then there’s Japan.

Japan is trying to work itself through a bubble that burst eleven years ago when it had billions pouring out of overvalued stock and real estate markets. It may be years still before the country rebounds. Smart investors like Leah Zell, however, know that there are some tremendous values in Japan and other ravaged economies, so that’s another reason to favor a patient overseas diversification scheme that includes the Pacific, Europe, and South America. Sooner or later Japan will turn around and the People’s Republic of China will be a prudent place to invest. You need a qualified mutual fund manager to get you there.

There are also choices within international funds from which to choose style and capitalization. Zell, for example, is a specialist in small- to mid-cap value stocks overseas. As with domestic stocks, there’s a sizable advantage in choosing value over growth, as the table below indicates:

VALUE OVERSEAS: A WINNER | ||

Category |

| Annual Return (1973–2000) |

Foreign large value |

| 15.5% |

Foreign small cap |

| 13.9% |

Foreign large cap growth |

| 11.7% |

Source: www.tamasset.com. | ||

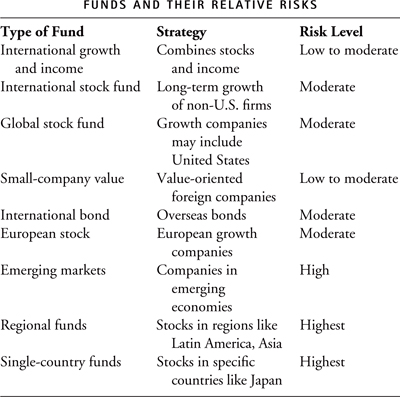

Types of International Stock Funds

Like U.S. funds, foreign funds can get highly specialized. I suggest that you seek as much diversification as possible to avoid region or country risk. The following table outlines the kinds of funds and the relative risks they incur.

How Much Should You Own in Foreign Funds?

Just as you would not build a portfolio made of only one stock, bond, or piece of real estate, you would not want your portfolio dominated by foreign stocks. Every portfolio needs to have some foreign stocks. How much depends upon how much risk and volatility you can tolerate.

As a rule, the more conservative portfolios have no more than 15 percent of the total allocation in foreign stocks. The most aggressive portfolios have no more than 40 percent in overseas issues. Since you need room for large-cap, mid-cap, and small-company stocks, bonds, real estate, and cash, it would be imprudent to suggest that foreign stocks would ever account for more than 45 percent of your holdings.

Those who think they can “time” a bull market for foreign stocks are constantly looking at last year’s hot performers and missing the boat. I can tell you from personal experience how things can turn out badly. In the mid-1990s, the investment world was tittering at the prospect of “emerging markets” as the next big engine of growth. Countries like Singapore, Indonesia, and Malaysia were referred to as “Asian Tigers,” even though they had tiny stock markets and were subject to huge swings in local currencies.

Nevertheless, trillions poured into these countries and mutual funds sprouted up like mushrooms after a June rain to trumpet the gains from emerging economies. That’s when investors like me thought they were going to make a quick 60 percent to 100 percent return through emerging markets mutual funds. As is the case most of the time, the mutual funds and brokers did much better than I did. I bought into several funds advertising stellar returns from the prior year. After a so-so year, most of those “tigers” had turned into scared mice and their currencies were plundered by investors moving their money to other places and speculators who added to the economic carnage. Because the Asian money was moving so fast and furious back to safer Western shores, Alan Greenspan fiddled with the money supply and interest rates to avert a market meltdown, but those markets have yet to recover. After a few losing and subpar years, I exited my international funds, tail between my legs, so to speak.

Having shared with you one of the cardinal rules of investing—don’t invest based on last year’s performance—I can still heartily endorse some stake in overseas markets. The fact that they are not always moving in the same direction as U.S. stocks is one of the best reasons to think that if there’s a bear market in the United States, holding foreign stocks will give you positive returns.

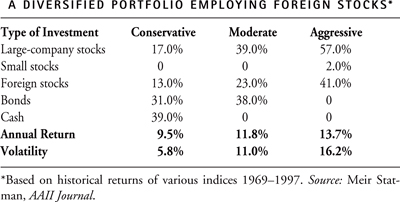

Professor Meir Statman, who teaches finance at Santa Clara University, has calculated how portfolios composed of various proportions of foreign stocks and U.S. large caps, small caps, bonds, and cash performed from 1969 through 1997. Here’s what he found:

With this example, you see that the more risk you take, the greater the return, and vice versa. I would beg to differ with the professor on the allocations. I think that every investor—no matter how conservative—needs to have some small-company stocks because of the outstanding long-term returns. The larger point is that adding foreign stocks will boost returns. For most investors, the proper amount falls between 10 percent and 25 percent.

What you need to achieve with international funds is an efficient frontier, a state in which you are reaping the maximum amount of return for the lowest amount of risk. Generally, investing your portfolio in no more than 30 percent foreign stocks will give you the benefits of diversification while boosting returns. This percentage varies over time, so it’s a starting place.

What Do You Do When an Asset Class Hits a Bad Year?

Like U.S. stocks, foreign stocks will hit their bad patches. Since they run in cycles of several consecutive years (this is typical but not always true), you can count on some underperformance when U.S. stocks are roaring. My suggestion is that you keep the foreign stock allocation at your comfort level. A 10 percent allocation is best for those who don’t want to feel much pain; up to 30 percent is fine if you feel especially adventurous. If you see a fund hit double-digit losses—and that doesn’t feel right—then switch to more conservatively managed funds, but keep in mind the manager’s long-term record. Zell’s fund, for example, had an awful year in 2000, but that doesn’t mean you should abandon her fund, because her investment style often takes years to reap rewards. It all depends on how patient you are.

You can no more predict which country or region will have a good run than you can foresee which U.S. market sector will do well. International investing becomes even more prickly when you take into account political, currency, and regional risks. Understanding international investing is, in the words of Charles Morris, “the murky depths of the economy. Like a plumbing system, it is invisible when it is working well, but a broken pipe can be a disaster.”

As with so many other types of investments, it’s impossible to predict where countries and regions are going to be from year to year, so you need to hold them for at least five to ten years to take advantage of cycles that will eventually run in your favor. It will be a pleasant surprise when the other shoe drops in the U.S. market.

* * *

Speaking of shoes, have you heard the Brothers Grimm’s tale about the elves and the shoemaker? There once was a poor shoemaker who had leather enough for only one pair of shoes. Exhausted from thinking about his ill fortune, he went to sleep that night, leaving the pair of shoes unfinished. Rising that next day, having faith that things would turn around (he had also said his prayers the night before), he found a perfectly sewn pair of new shoes sitting on his cobbler’s bench. They were masterfully crafted, with not a stitch out of place. A buyer soon appeared for the shoes and paid twice the normal price for them because of the outstanding craftsmanship. Now the cobbler could afford enough leather for two pairs of shoes, which he cut out before he went to bed. The next morning, the shoes were finished again and were as exquisite as the original pair.

Naturally, the cobbler and his wife were more than curious as to how the shoes were being made in the dead of night by unseen hands, so they hid in a corner and waited the next night. At midnight, they saw two naked elves come into the workshop and finish the shoes. They didn’t stop until they had finished their work, then ran swiftly away. The couple went to bed and had a discussion of the night’s events the next morning. “Since the elves brought us prosperity, we should make them fine shoes and clothing.” And so they did and laid out the garments and shoes and waited until midnight. The elves saw the charming clothes and footwear, put them on, and did a joyous dance in utter delight. They leapt around the room in glee, then scurried out the door, to be seen no more. The cobbler and wife, however, still fared well in all that they did.

There are happy, industrious elves lurking in the market. They are foreign to us, but they are there, nevertheless. We never see them, nor can we predict when—or where—they’ll bring us prosperity. You just have to wait for them to show up and do their handiwork.