CHAPTER 8

Doing It Yourself: An Integrated Approach to Stocks

Oh money, money, money

I’m not necessarily one of those who thinks thee holy,

But I often stop to wonder

How thou canst go out so fast when thou comest in so slowly.

—Ogden Nash

Having spent a great deal of this book extolling mutual funds and the value school of investing, I’d like to take you down a different road. You can build a portfolio of growth stocks on your own—and make money with moderate risk. To those who grew up thinking only a broker, banker, or money manager should be touching money, this may be quite a turnabout.

I’ve spent untold hours meeting with individual investors who’ve been successful at building their own portfolios. They don’t use complicated formulas to pick their own stocks and they certainly have no expectation of beating the market. These “self-reliant” investors build portfolios of largely dividend-producing stocks that grow over time.

In this regard, I’ve also had some experience. My wife and I have been picking individual stocks—in addition to our mutual funds—for the past six years as part of our family investment club, “The Wall Street Prowlers.” It’s been an educating and often-trying experience, as we’ve lost family members to disinterest, divorce, and other concerns. After a watershed year in 1999, the years 2000 and 2001 proved especially challenging as we watched nearly all of our holdings get clobbered. Undaunted, we not only stayed the course and held on to every one of our stocks (GE, Walgreens, RPM, Sysco, Oracle, ADC Telecom, Merck, and Motorola), and we bought more stocks in some of the most bruised and battered issues. ADC Telecom, which dropped from $40 a share to $3 a share, hurt the most, but our faith in the company’s prospects made us buyers, not sellers. Although the value of our portfolio dropped by nearly 25 percent in a year’s time, we are long-term buy-and-hold investors. We chose our stocks after months of research; unless the companies do something drastically wrong, we’re going to hold until somebody in the club needs to cash out.

George Fisher is perhaps the best example of someone who has done it on his own, with no connection to the world of high finance, mutual funds, or money management. Fisher has hustled most of his life. For fourteen years he sold roofing and molding materials for Georgia-Pacific. He quit that job in his mid-thirties to buy a company that made water pumps. The company made money, but the ninety-five-year-old founder and sixty-five-year-old son running it had seen better days. Fisher and his father-in-law turned it around, getting sales to grow 25 percent a year, before selling it in 1989.

Starting his own company, Fisher then decided to become a manufacturer’s representative for Tecumseh engines, specializing in pump engines for the Asian market. He helped farmers keep water flowing in rice paddies throughout the Philippines, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Taiwan, and Korea. He would travel to Asia two or three times a year and visit seven or eight cities each time he went. Although not every pump could be adapted to the Asian market, Fisher did well until 1997, when a combination of factory overcapacity and the Asian currency collapse took its toll. After the meltdown, the engines he sold cost twice as much in local currencies as they had before the debacle. He was also up against tenacious Japanese competition, which was quick to offer creative financing. His business evaporated.

After “getting sick of writing please hire me letters” in 1997, Fisher decided to start a new business. He had been investing on his own since 1970 and was determined to turn that into a new enterprise. A newsletter focusing on stocks that offered dividend-reinvestment plans (DRIPs)—Power Investing with DRIPs—became his new undertaking. He would offer one of three newsletters with advice on DRIPs, and was certainly the unproven new kid on the block. Having been chastened by “thousands of dollars of losses using brokers’ advice in the 1970s,” Fisher was determined to find a low-cost strategy that worked.

DRIPs are offered by companies as a way of keeping investors engaged in the company’s progress. Generally, DRIPs are available from established companies that pay out a percentage of profits in the form of a dividend; DRIPs allow investors the chance to reinvest that dividend in new shares. The little bonus that DRIPs offer is that all new shares bought with reinvested quarterly dividends—or by writing a check—are purchased at no commission. This is the company’s way of saying “Thanks for investing, and by the way, would you like another helping of our shares?”

Fisher likes DRIPs because there are a wide variety of them in nearly every industry. DRIPs were originally born in the 1960s to help companies build capital by cultivating a loyal base of investors. Some seventeen hundred public companies offer DRIPs, all of which only require that you buy one share to get into the plan. Since the Securities and Exchange Commission relaxed the rules regarding DRIPs in the mid-’90s, these plans have exploded in number and popularity. The plans are simple in design: You buy the shares, which are held by a “transfer agent,” usually a bank. The transfer agent handles all of the transactions and recordkeeping and you get a statement every quarter.

Better yet, a growing group of companies also offer direct investment plans, or “DIPs,” which will sell you that first share directly, so you pay no commission for any shares you purchase from those companies. Some notable DIPs are offered by McDonald’s and Chevron Texaco. It may seem dangerous to buy stock directly from the issuer—after all, aren’t we trained to call our brokers, bankers, or money managers for advice on the most insignificant financial detail?

Fisher estimates that of the 45 million Americans who invest in the stock market, only 5 million know about DRIPs and DIPs. Not only do DRIPs and DIPs give you a virtually low-cost way to invest, they give you access to thousands of quality, brand-name companies like General Electric, Merck, and Wal-Mart. In fact, DIPs in particular offer individual investors advantages not even mutual funds can boast—they can buy stocks at no commission for very low initial investments. Because DRIPs allow you to invest at such a low cost, Fisher says he “hates mutual funds as an investment vehicle.” He offers this example of how mutual fund fees can eat up returns over a lifetime:

Let’s say Joe Investor invested $10,000 every 10 years in stock mutual funds from age thirty until age sixty. He has paid 1.5 percent every year to the funds to manage his money. He retires at age sixty and discontinues his fund contributions, letting the money accumulate until age eighty-five, when he passes away with a smile on his face. He’s made 11 percent on his funds—in line with the historic return for the S&P Index. He’s left his heirs $2,437,797, not bad for an investment of $40,000. Had Joe invested in DRIPs at an 11 percent annual return, however, he would have turned in his grave. His DRIP portfolio would be worth $5,246,893. Over his lifetime, he’s paid a total of $430,000 in fund fees.

Since you start out with one share and there’s no requirement to buy additional shares, you can build a DRIP portfolio with very little money. Most mutual funds require that you open a fund with at least $2,000; some of the larger funds now require $25,000 or more. If you don’t have that much money to commit, then DRIPs are often a sensible way to start off a long-term investing plan.

WHAT DRIPS AND DIPS COST

Although there are typically no commissions associated with DRIPs and DIPs, nearly every plan charges a transaction fee per purchase or sale. A handful of plans even charge a small commission. Fisher says 60% of the companies he follows only charge fees when shares are sold. Here’s a range of small fees charged by DRIPs and DIPs:

FEE RANGE FOR DIPS AND DRIPS | ||

Type of Fee |

| Amount |

Setup fees |

| $5 to $15 to establish account |

Termination fees |

| $5 to $15 when you sell all shares |

Commissions |

| From $0.15 to $2 per share |

Source: Power Investing with DRIPs. | ||

DRIPs are also extremely popular among investment clubs, small groups of investors who pool their money to buy stocks for the long term. (If you want to know more about investment clubs, consult my Kitchen-Table Investor or Investment Club Book.) Whether you are with a club or on your own, the DRIP is the natural vehicle to anchor your portfolio because you can invest as little or as much as you want every quarter through “optional cash investments.”

Using his own numerical rating system, Fisher selects DRIPs for a variety of portfolios that are screened for risk. His conservative portfolio usually consists of old-line companies that are paying consistent dividends. More aggressive portfolios focus on companies whose financial ratings may not be as strong as the older companies, but are poised for growth. This is an outline of his rating system:

• Start out with the best managed companies. They should have at least ten years of earnings growth and dividend payments.

• Look for the Standard & Poor’s (S&P) equity ranking. The S&P system rates companies using a letter scale, “A+” being the highest and “not rated” being questionable. Fisher prefers “A+” to “B+” companies. The S&P reports are available in the business reference sections of most libraries. Fisher notes that by only selecting “A+” companies, you eliminate 90 percent of the companies offering DRIPs.

• Look for companies that are priced favorably for today’s market. Has the company recently dropped in S&P ranking? Have the earnings estimates and returns on equity been below industry averages? These companies may be bargains.

• Fisher likes companies that are growing 20 percent a year, although those companies may be hard to find in a slack economy. Ideally, these companies are paying out no more than 65 percent of their earnings in dividends. This “dividend payout ratio” is a calculation he uses to find companies that are paying dividends, yet retaining enough earnings to grow their business.

• Are earnings consistently growing over the past decade? Spotty earnings records are good ways to weed out inconsistent management. “Excellent management will always find a way to make a profit. These are the companies you need to be investing in.”

• What are the consensus brokers’ estimates for earnings? Look at earnings estimates for this year and next year. Is the company still growing? Check out www.zacks.com (an independent research firm) or www.morningstar.com for analysts’ opinions.

• The company’s current p/e ratio should be below the average of its five-year range and below industry averages. This is one way of spotting a company that is underpriced.

• Look at the company’s next year PEG ratio, also known as the Y-PEG. This number shows the relationship between the current p/e ratio to the company’s anticipated earnings-per-share (EPS) growth rate. The PEG formula is the current price divided by the current EPS divided by the anticipated EPA growth rate. Although this sounds complicated, PEG ratios provide a glimpse into how a company may grow its earnings. When the p/e ratio equals EPS estimates, the PEG is 1.00. Any PEG under 1.00 is considered a good value and should be considered for a purchase if all of the other factors line up. A PEG of 0.5 or less is considered a great value. You can find PEG ratios at www.aaii.org or in investment reference materials in the library.

“Investing is about finding value in top-quality companies,” Fisher explains, sounding like investing icon Benjamin Graham. Offering model portfolios of his favorite DRIPs, Fisher claims that his best portfolio returned 18 percent in 2000 when the overall market lost money. Since he doesn’t manage other people’s money, his numbers are not audited, but his overall approach features lower risk than most stock mutual funds. Nevertheless, you don’t need to read his newsletter to find great DRIPs to invest in for your portfolio, although his approach is a worthwhile launching pad. It’s a truly integrated method for the self-reliant investor. If this is the kind of research you will relish, then sample his cooking.

Why DRIPs Make Sense If You Want to Do the Homework

You can literally build your own mutual fund with DRIPs. Like a truly diversified mutual fund, however, it makes sense to build your portfolio so that it includes stocks from a number of different industries. It would be unwise—and highly risky—to concentrate all of your DRIPs in utilities, food service, or financial services in case the market turns against those sectors. Start off with companies you understand. Utilities are a natural first step. You know what they do and how they do it. They typically pay higher-than-average dividends and nearly every established utility has a DRIP. Some groups are so broad that they include subsectors. Financial services is a case in point. Within that group you have companies ranging from those that are cash machines, like insurers, to those that are highly sensitive to the economy, like retail stock brokers.

Here are some often recession-resilient industries that you can consider when diversifying your DRIP portfolio. If you had one stock from each of the following industry groups, you’d be fairly well diversified.

• Utilities. Electrical, telephone/telecom, gas, and water all pay healthy dividends.

• Financial services. Some of the oldest institutions have the steadiest dividend payments. These include all types of insurers (property, life, brokers), retail banks, savings and loans, stock brokers, investment banks, and “nonbank” finance companies. The older, more established banks and insurers hold up particularly well during a recession.

• Manufacturers. There are thousands of manufacturers that have been around for fifty years or more. Some are well known, like GE; others make more obscure products, like Illinois Tool Works.

• Food and food service. Always reliable stocks in a downturn because they hold their value and pay a steady dividend, and people still buy food when times are bad.

• Energy. Natural gas and oil producers, oil service, and energy traders typically channel their profits into reliable dividends.

• Retail. These are among the most visible companies because they are in nearly every commercial district. They include Wal-Mart, The Home Depot, and Walgreens.

• Technology/telecom. This is perhaps the most sensible way of investing in tech stocks. You can buy low and hold on.

• Materials and industrial companies. No big names here, but they make everything from paint to oil rigs.

• Tobacco. If you don’t mind owning these stocks, they are among the most consistent dividend payers around.

• Defense manufacturers. Again, if this passes your ethical screen, you can count on dividends because these companies usually have a steady book of orders from Uncle Sam.

Employing Dollar-Cost Averaging: You Don’t Have to Time the Market

When’s the best time to buy a DRIP? After you’ve done your research and selected a quality company. Remember, you want to hold this company for several years, so the idea is to buy a business that you won’t want to sell until you really need the money. A DRIP portfolio is the opposite of cash. It’s not for money you’ll need within the next ten years or more if you do things right. (A personal note: My wife and I have a family investment club that employs DRIPs. We hope to use the proceeds for our two daughters’ college educations, which are about fifteen years down the road at this writing.)

The best tool to employ when buying DRIPs is dollar-cost averaging (see table). This is a fairly simple technique that allows you to buy stocks on a regular basis, without timing the market or worrying about whether you are buying in at a peak or valley. You just keep buying.

What this dollar-cost-averaging example shows is that you avoid buying all your shares at the market’s peak in November and buy more shares when the stock price sells off. Since you can never guess correctly when a stock price will hit its high or low for the year, this way of investing gets you more shares when the price is down.

But What about Taxes? Aren’t Capital Gains Better than Dividends?

The tax laws change every few years to reflect shifts in politics and investing strategies. The last wave of tax-code changes reduced estate taxes and capital gains taxes. While the estate taxes are only reduced until 2010 (try to die before then if you want to leave a bigger pile for your heirs), the capital gains taxes will be as low as 10 percent, depending on your tax bracket. Your marginal tax rate roughly reflects what you’re going to pay, up to a maximum of 20 percent.

DOLLAR-COST AVERAGING: BUY LOW AND HIGH AND HOLD | ||

$50 a Month in American Pie, Inc. | ||

Month |

| Stock Price |

January |

| $9.00 |

February |

| $11.50 |

March |

| $12.00 |

April |

| $10.00 |

May |

| $8.00 |

June |

| $9.50 |

July |

| $8.50 |

August |

| $9.00 |

September |

| $10.50 |

October |

| $11.00 |

November |

| $12.00 |

December |

| $8.00 |

| ||

Average Purchase Price: $9.92 | ||

Amount Invested: $600 | ||

Capital gains are increases in the value of what you own through appreciation, typically through a rise in market value. Dividends, however, didn’t get the same favors from Congress and are taxed as ordinary income, the same as your wages at your marginal rate. So if you are taxed at the 33 percent level (28 percent federal and 5 percent state taxes), that’s what the government will take if you are paid dividends. It hardly seems fair.

At one time in the not-so-distant past, the first $700 of dividends were exempt from income taxes and capital gains were taxed at higher rates. That was during a time when dividend-paying stocks were held by people who never sold them and relied on them for retirement income. You probably know someone in your family who owned AT&T for the dividend and died, leaving someone to inherit it. Now there’s double taxation on dividends: both the corporation and you have to pay taxes on them.

Because of the current tax code favoring capital gains taxation over dividends, income-paying stocks lost a lot of sizzle and newer, higher-flying companies invested profits in capital equipment, giving stock options to employees, acquiring smaller companies, or buying back their own stock. Fisher notes that in 1998 alone U.S. companies bought back $209 billion of their own shares instead of paying dividends. In a market downturn, however, dividend-paying companies look like firemen when you see smoke coming from your house. You want them to be there because they offer a bit of security.

The Security Blanket

The most compelling logic for a dividend is that it offers a stream of earnings that can be converted into cash payments for you, the investor. Companies without earnings can’t pay a dividend and their share prices are the first to fall and take the biggest hits overall. A dividend is a tiny insurance policy and makes dividend payers competitive against bonds. As such, a dividend boosts total return, which you may recall is capital appreciation (increase in market value) plus income (the dividend). When the bear market starts to growl, the more conservative institutional investors dump their speculative holdings in favor of the consistent dividend payers because they know in a downturn they will at least get that dividend.

Given the choice between capital appreciation and a dividend, in times when corporate earnings and the economy are growing across the board, pick a company that provides the appreciation. When earnings turn flat and the economy heads south, having dividend payers is like having a security blanket. There is also a subtle relationship between dividend payers and the pure-growth companies that dominated the 1990s.

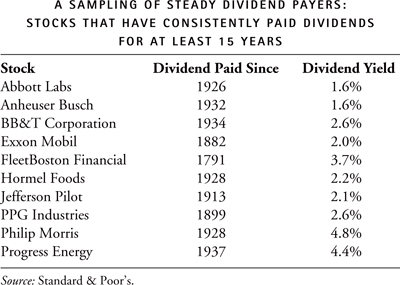

For years, the stodgy dividend payers were seen as behind the times and their stock prices languished. Old stalwarts that dominated the food, financial, utilities, and energy industries were neglected in favor of “I gotta have it” technology companies. As a result, share prices for entire out-of-favor industries were undervalued. Enter the value managers, scooping up perfectly profitable companies that the rest of the Viagra-besotted market ignored. When earnings evaporated for the techs and dot.coms, the big bananas running institutional and mutual funds did sector rotations into the dividend payers. That means they dumped the glamour boys and went elsewhere. Once wallflowers, the neglected dowagers became princesses in a growling market. So dividend payers were part of a move to value. They had earnings and were willing to share them when so many earnings reports were disappointing so many. That’s one of the reasons why the Wilshire Value Index was only off 0.7 percent when the Wilshire Large Growth Index was being clobbered 42 percent from the March 2000 market peak sixteen months earlier. Dividend yields rise as part of the equation when stock prices fall. Higher-dividend companies qualify most of the time as being out of favor, so they are natural candidates for any value or income investor.

When you consider the handful of predictions in chapters 1 and 2—that the average returns for stocks will be in the single digits unless a high growth period returns—dividends become as important as trunks on elephants in achieving an inflation-beating total return. No less than Jeremy Siegel of the Wharton School of Finance pronounced in the summer of 2001 that “in the future, I believe that more attention will be paid to dividends and current earnings and less to growth.”

Does the dividend yield of a stock signal a good time to buy and sell? Not really. According to Thomas Saler in Taming the Bear: How to Invest in Stocks without Getting Eaten Alive (Globe Pequot, 1994), “by itself the dividend yield on stocks tells you little about when to sell and even less about when to buy.”

If You’re In for a Penny, You’re In for a Dollar

The key to building your own portfolio—even in bear markets—is consistency. If you are confident in your research, then keep buying the companies you like. Dollar-cost averaging is one of the best techniques to keep your portfolio growing. Although it’s contrary to human nature to buy stock when the price is down, that’s the best time to lower your average cost per share—and ultimately boost your profit when you sell. This technique also works with mutual funds, but to make it work, you have to do it on a regular basis—every paycheck, monthly or quarterly.

In a bear market, you automatically become a value investor. You are buying when others are selling, just like some of the top professional managers you’ve met in previous chapters. While it flies in the face of logic to buy during major market declines, that’s when you’ll find the greatest bargains. If you’ve done your homework, the rebound will be especially sweet.

DRIP Resources

There are several excellent sources of information for DRIP investors.

• George Fisher’s newsletter Power Investing with DRIPs (www.powerinvestdrips.com; 847-446-4406) employs a comprehensive approach, but it’s pricey for the average investor at $99 annually. A better value is his book All about DRIPs and DSPs (McGraw-Hill, $16.95), which lays out his DRIP strategy in colorful detail.

• The most complete set of DRIP resources is from Charles Carlson at Horizon Publishing (www.dripinvestor.com; 219-852-3220). Horizon publishes The DRIP Investor, a newsletter that follows both DIPs and DRIP plans and recommends portfolios. The newsletter, also $99 a year, has a wealth of information on the subject and updates changes in plans and suggested portfolios. Carlson has also penned several books on the subject, the most notable being Buying Stocks without a Broker (McGraw-Hill, 1999).

• Another useful resource is from Temper of the Times Publications (www.directinvesting.com; 800-295-2550), which also publishes The Moneypaper, Direct Investing, and The DRP Authority newsletters. Its Temper Enrollment Service features access to one thousand DRIP plans.

• Members of the American Association of Individual Investors (www.aaii.com) receive an annual issue of their AAII Journal that contains an extensive list of available DRIPs. Their Web site also has a generous number of articles on investing using a dividend-focused strategy.

• Another long-standing favorite among dividend-savvy investors is Geraldine Weiss’s Investment Quality Trends newsletter (www.iqtrends.com; 858-459-3818), which tracks a number of stocks that she recommends. She’s also the coauthor of The Dividend Connection (Dearborn Financial, $24.95), which, while out of a date, is a good starting point for learning about the subject.

• The National Association of Investors Corporation (www.better-investing.org) is the non-profit mother ship for investment clubs and features two low-cost DRIP programs, from which you can enroll in DRIP stocks if you are a member. You can join as an individual or as a club.

• In the library, consult Moody’s Handbook of Dividend Achievers, Standard & Poor’s Industry Reports, and The Value Line Investment Survey. All contain extensive information on earnings, predictions, company ratings, and dividend history.

There are more detailed resources in the back of the book on these organizations.

If History Is Any Judge, Dividends Will Rise Again

As I write this in late 2001, the S&P 500 dividend yield is a meager 1.3 percent. Historically, stocks have yielded close to 4 percent over most of the past century. While you can’t argue that Congress will turn back the clock to favor tax treatment of dividends, in a low-return environment stocks with dividends are more attractive than those without dividends— they simply have to compete with bonds. Investors will continue to reward stocks that take more risks to produce higher returns. That much is a given. Dividends, however, serve as a way of tempering risk if you’re not willing to make huge sacrifices for the return.

No matter how Uncle Sam or Wall Street sees it, there is something virtuous about a dividend. It’s a reward for holding a stock. The longer you hold a stock, the more dividends—and dividend increases—you will receive (if the company stays healthy). In that light, dividends are about saving and reinvesting profits, the essence of thrift. On that subject, I know of few wittier experts than Richard Saunders, the “Poor Richard” of Ben Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack. Here’s one of Franklin’s thoughts on thrift as rendered by Poor Dick:

How to Get Riches

The Art of getting Riches consists

very much in Thrift. All men are not equally

qualified for getting money, but it is in the power

of every one alike to practice this virtue.

He that would be beforehand in the World,

must be beforehand with his business:

it is not only ill Management, but discovers a slothful

Disposition, to do that in the afternoon,

which should be done in the morning.

Useful attainments in your minority

will procure riches in maturity, of which

Writing and accounts are not of the moment.

Or, as Franklin opined in another edition of his sage almanac, “there are three faithful friends—an old wife, an old dog and ready money.” Steady dividends also count when you need to restore your faith in capitalism.