CHAPTER 9

Buying into Long-Term Trends and Holding On for Dear Life

The art of living resembles wrestling more than dancing, for here a man does not know his movement and his measures beforehand. No, he is obliged to stand strong against chance, and secure himself as occasion shall offer.

—Marcus Aurelius

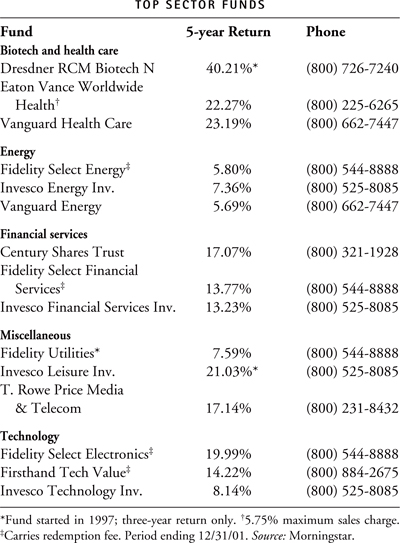

“It’s not that I’m competitive, I’m focused.” The words burst from Sam Isaly’s mouth like pellets from a shotgun. Even though he is uncomfortable after a flight from London to Chicago, his persistent smile is borne of the confidence of managing money well and being right when others are wrong. Running the $1 billion-plus Eaton Vance Worldwide Health Sciences Fund, one of the top health sciences stock funds over the past three years, you have to be focused. Even with his “A-list” education, Isaly knows that he has to put up numbers every year in his business. Armed with a degree from Princeton, where one of his professors was Burton Malkiel, author of A Random Walk Down Wall Street, and an M.S. in economics from the London School of Economics, Isaly’s business is to know the world health-care scene—and buy risk-laden stocks that may not pay off for several years.

Working as a pharmaceutical and international investment specialist for the past thirty years, Isaly looks for biotech, pharmaceutical, and health-care industry stocks from Tokyo to Tel Aviv. Like most top fund managers, he is either on the plane or on the phone and requires that his staff meet on Sunday afternoons when there are no distractions. Isaly’s competitive nature is such that he revels in what his competitors own—and his fund doesn’t—because he believes he has a good sense of what’s overvalued and what’s not.

Isaly’s “sector” fund, which only invests in the health-care industry and related businesses, is to diversified index funds what Antarctica is to Zimbabwe. His fund only holds from forty to fifty stocks, compared to hundreds for the average index fund. He makes a few investments and hopes to beat the market, which he thrashed in 2000 with an 81.56 percent return. Except for 1995, when the fund was up 61 percent, last year was more the exception than the rule. The long-term record of the fund, however, has bested some 80 percent of the competition and averaged 22.58 percent a year over the past five years, beating the S&P 500 by nearly 9 percent and the broader Wilshire 5000 by nearly 11 percent, according to Morningstar. Through October 30, 2001, it was the third best-performing fund out of one thousand funds rated by Lipper Analytical services.

Although Isaly’s fund is incredibly volatile and definitely not for nervous nellies—it has a standard deviation of 40.87—it is less risky with a fund beta of 0.66 than owning the S&P 500 (1.00 being the average of the index). When you look at the fund’s holdings, you see nearly all of the big “pharmas”—Pfizer, Novartis, Lilly, Abbott, American Home Products, Pharmacia, and Schering-Plough. These large-cap drugmakers account for nearly one-third of the portfolio and add stability to the remaining holdings, which are “emerging” biotech and pharmaceutical companies that are not making money yet (about one-third of Isaly’s total portfolio).

Since he invests in some of the riskiest startups in an as-yet-unproven business, biotech, Isaly controls his risk exposure by investing no more than 5 percent in each company. For the smaller companies, he is generally under 4 percent per stock. Brand-new companies are allocated no more than a 1 percent stake.

“Our moderate position size is appropriate to the risk we take. We know the smaller companies can go up ten times in value, but they are no more than a 5 percent position. Since we assign about four ‘names’ (companies) per analyst (there are twelve), we have one of the lowest holdings-to-analyst ratios in the business.”

By assigning fewer stocks to his analysts, who act as stock pickers, researchers, watchdogs, and champions of the stocks they monitor, Isaly can keep a better eye on the companies he owns, many of which are still shooting for their first blockbuster drug. All told, Isaly estimates his portfolio consists of 50 percent established companies and 50 percent new companies. If an analyst suggests a company to buy, Isaly makes them sell a company. “You have to fight for space in the portfolio.” Isaly’s research team is set up to buy companies with promising products. Not only are they picking the Mercks and Pfizers of tomorrow, they need to know when the companies will be profitable.

“We need to know who’s going to make money and when. We expect to have eighty profitable companies by 2004. We make most of our money if we pick a company two years before it’s profitable and hang on for two years after that.”

Isaly’s style is like prospecting for gold, only he’s surveyed every creek and valley, started digging and panning, and inspected the terrain years before the other prospectors have arrived. He grills management, consults the four analysts who hold doctoral degrees on his staff, gets on planes, and goes all over the world. When he hits paydirt, he does well. A company called Gilead that the fund owned went public at $8 and shot up to $53. He thinks it will hit $100 and plans to hold it for five to ten years. Although he sounds brash hyping the next biotech marvel, he’s as far as you can get from a “pump and dump” broker. He insists he’s “an investor and not a collector.”

Isaly’s method is rooted in knowing the companies he buys better than a bridegroom knows his bride. He doesn’t want character traits, he wants amounts and dates when things are going to happen. It’s like a fiancé asking his betrothed, “Sure you’re going to be a corporate lawyer. When will you pass the bar and what will be your average earnings for the next ten years after taxes?”

“I want experienced management,” Isaly continues without a pause in his staccato patter. “Have they done it before [made new drugs]? Are they good business people and scientists? Do they have the pedigree [education]? I get very nosy. I want names [stocks] nobody else owns. If everyone owns a company like Merck [he doesn’t and is glad he doesn’t], everyone performs the same.”

Despite the fact that pharmas and biotechs had a stellar year in the midst of Wall Street’s burst bubble—the sectors were up 30 percent and 50 percent, respectively, in 2000—Isaly still sees ample growth for these industries. Of the twenty biotech companies that are profitable, they are growing earnings 20 percent a year. It will be rocky in the interim. In 2001, Congress was pushing to provide prescription coverage to Medicare recipients, which is a huge wildcard for the pharmas. Most health-care fund managers see Medicare changes as inevitable, and largely negative in the short term, since they will force the drugmakers to give large discounts to the government and depress profits. Isaly claims that the market has “priced in” this possibility already, although it’s hard to tell what will actually happen until a bill reaches the president’s desk.

Keeping up with all of the advances in health care can be bewildering, but Isaly won’t be left behind on important new drugs or procedures. He won’t take incoming cell phone calls in the office because he doesn’t want anything to interfere with his work. When he’s not working, he’s with his family, fishing off Cape Cod or “simply watching the wind blow in the trees” from a country house in rural Pennsylvania. Despite having more money than time to spend it, he takes the bus to work. All New York City buses can accommodate his wheelchair [he was partially paralyzed in a high school wrestling accident], and after the twenty-minute commute, he is back to thinking about “putting up numbers so high on the board [annual returns] that nobody will be able to take them down.” No, he’s not competitive, he’s focused—like a laser beam on a diamond.

Big Themes and How You Can Invest in Them

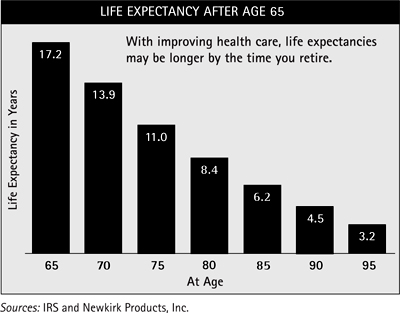

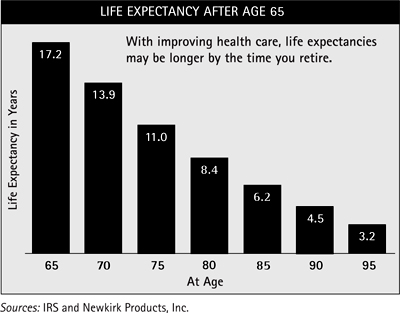

Demographics are destiny. Or that’s what a handful of futurists have been predicting over the past few years. Just look at what has happened since the end of World War II and you can get a picture of how dramatically things have changed for our species. Most Americans forget that when Franklin Roosevelt instituted Social Security in 1935, he never thought it would burden future generations because most people didn’t live to be sixty-five in his time. Now we have a boom in eighty-year-olds and one-hundred-year-olds; longevity and not outliving your nest egg have become two of the most powerful themes of the twenty-first century.

The news has been in for a long time. Life expectancies are longer. The drugs to get us there are better. Biotechnology will allow us to rewrite biology to repair organs, mend stroke damage, strike down cancer, and eliminate horrid diseases in the womb. It’s a bit scary that we have such knowledge, but it’s all in the quest of longer life and the holy grail of immortality.

Well, nobody is going to live forever, but we can enjoy the ride a bit more and make some money along the way. Sector funds shine a spotlight on health care and other industries, such as software/electronics, financial services, energy, precious metals, regions (see chapter 7), and subsectors of industries (brokerage, insurance, medical delivery, etc.). Sector funds are popular because they allow investors to make streamlined bets on industries or parts of industries. These are not diversified funds investing across the board. They are usually betting on one race at a time with only a few horses.

When it comes to health care, an increasingly popular sector in recent years due to the growing prominence of biotechnology and drug therapies, health-care sector funds are thriving due to speculation and expectation. Speculation is a fixture of any market. Expectations can be even more troublesome since the majority of them—when it comes to stocks—are never fulfilled. There are more blind alleys in the biotech industry than mutual fund companies are willing to admit. And for every blockbuster drug, a drug company has tried some twenty thousand other compounds that didn’t work. For every Prozac, Zocor, and Viagra, there are warehouses full of experiments that went nowhere.

Nevertheless, the health-care industry is built on expectations—and hope. We have come to accept that there will be cures for the most devastating diseases because the pharmas have a track record of delivering. Before World War II, modern antibiotics were unheard-of, there were no drugs to control cholesterol or blood pressure, and chemotherapy for cancer was practically nonexistent. And forget about chasing away depression with a pill or improving your sex life. Big bands and booze were the main drugs of the ’40s. (I’ll take the big bands over booze any day.)

The pressure to manufacture cures is part of the health-care establishment. Our government pours billions into universities and pharmas to find these cures. It is a part of our way of life. When we grow old, we expect Medicare to cover the cost of nearly every ailment (if you don’t have insurance before then, you’re out of luck). And with genomics, stem-cell research, and even more powerful computers coming on the scene, the advances in medical science over the next decades will make Arthur C. Clarke blush. In reviewing all these developments, you need to follow how demographics are changing society and what it means to you as an investor. If you can invest to take advantage of these trends, the short-term market will become irrelevant. You will make money over time and you won’t care about bear markets.

• Preventive medicine will become the prevalent form of treatment. In many cases, preventive medicine isn’t a treatment at all: It’s exercise, wellness, a balanced diet, and diagnosing problems before they become life threatening. Consider that by the end of 2001, some 90 percent of insurance carriers will expand coverage or reduce premiums for those policyholders with healthy lifestyles. If you can control obesity, keep your cholesterol and blood pressure down, and exercise regularly, you have a good chance of living longer. There are a whole array of drugs, foods, and exercise regimens (health clubs) that bolster this lifestyle. It’s not surprising that a Louis Harris poll found that two-thirds of those queried said they have changed their eating habits in the last five years. We want to live longer and entire industries have been created to help us do that.

• Technology will mean more than higher productivity. The benefits to business are obvious: doing more work faster with fewer people. Technology, however, goes beyond cell phones. Some of the biggest advances in technologies are largely unseen but making a huge impact. Energy-saving technology and fuel cells may reduce our dependence on fossil fuels. The fastest-growing energy source is the wind. There are also ways of deriving energy from the sun, the ocean, and even garbage. Every major automaker is now committed to autos that run on fuel cells or “hybrids” running on a combination of gasoline and batteries. Of course, the mainstay of technology will still be information processing and communication. By 2005, 83 percent of American management will be “knowledge workers”—people who work directly with information processing. And five of the ten fastest-growing occupations by 2005 will be computer related. Although there’s a glut of processing and telecommunications capacity in 2001, the entire economy is being rebuilt around the speed of light—optical storage and transmission. In the long term, technology will be a constant and innovation will be rewarded. The future will require lots of technology, energy, and infrastructure. During the last industrial revolution, big money was made in the companies manufacturing the railroad tracks and buying the land. Today’s revolution will benefit those who are laying the big information pipeline and making the switches. It’s a safe bet.

• Biotechnology will be to the twenty-first century what computers were to the twentieth. I am tempted to bluster about coming cures for cancer, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and a host of other maladies. There will be thousands of small steps before that happens, however. Tremendous computing power is being put to work sorting out genes, proteins, and single molecules, which is a daunting process. Once this marriage is consummated, Isaly believes, “you’re going to see many more therapeutic drugs hitting the market in the future, especially mid-decade and beyond.”

• Aging Westerners will demand more service. I’m not referring to getting another glass of wine in a restaurant, either. Aging means more leisure time and less work; more disposable income and saving; more complex needs for services like estate planning and long-term care. The travel/tourism industry, for example, will nearly double in the next two decades. By 2020, there will be some 1.6 billion international travelers, up from 612 million in 1997, according to the World Tourism Organization. That’s good news for cruise operators, airlines, travel agents, and a host of support businesses. As people age, they save more and spend less, which will benefit the huge financial sector of banks, savings and loans, brokers, financial planners, estate planners, mutual funds, and insurers. And, as people become disabled, there will be a huge need for long-term care. Around 1900, the average life expectancy was forty-six years. In 2000 it was nearly eighty years, with the eighty-five-plus age group the single fastest growing demographic group. It’s a sure bet that older people will travel more, need more financial handholding, and require special housing needs. Funds and stocks that invest in these trends will do well over time.

• The vanity business will blossom. It already has. Plastic surgery and nutritional supplements have never been more popular. Skin improvement procedures are up 800 percent since 1990. Fitness-related products and services are growing at a steady 10 percent annual clip, notes American Demographics. The first wave of 77 million baby boomers (born 1946 to 1964) will be turning sixty-five in 2011 and will be doing anything they can to “keep on rocking” by staying out of the rocking chair. If it keeps you fit or purports to make you younger, the money will be spent.

• Productivity will increase because of technology, boosting wealth. Economists are in love with the idea of productivity, that is, working less and getting more done. Technology has made so many strides in boosting productivity that many economists insist that productivity was behind the boom years of the mid- to late 1990s. If you don’t have to spend as much time at work—and your wages are at least tracking inflation—then you reap an unseen benefit. You make more money without having to work harder or longer hours. That means you’ll have more money to invest and pay your bills and need the financial services to help you manage your money. Robert Davis and David Wessel explored the long-term benefits of productivity growth in Prosperity: The Coming 20-Year Boom and What It Means to You (Times Business, 1998):

If the economy chugs along at 1% annual growth in productivity, the income of the typical married couple would grow from around $49,700 in 1996 to around $60,050 in 2016. Add another half-percentage point of productivity growth, and the couple would make an additional $6,000 in 2016 … to middle-class families, $6,000 a year is eight months’ worth of mortgage payments on the typical newly purchased single-family home.

Technology puts money in your pocket indirectly, so you might as well invest in it long-term to benefit more directly.

SECTORS THAT DID WELL DURING ONE OF WALL STREET’S WORST WEEKS | ||

Sector |

| Change* |

Precious metals |

| 10.11% |

Water utilities |

| 8.10% |

Wireless communications |

| 4.12% |

Telecommunications |

| 3.26% |

Fixed-line comunications† |

| 3.15% |

*Returns reflect broad sectors for the week ending 9/21/01. While these sectors reflected Wall Street’s short-term ideas of safe havens, all but precious metals could be considered worthwhile long-term investments based on growth in those sectors. †Fixed-line communications represent telephone companies ranging from the long-distance carriers to the regional operating phone companies. Source: cbsmarketwatch.com. | ||

The following list doesn’t represent my endorsement of any particular stock or mutual fund type. I’ve picked a few notable leaders in each category and types of sector funds that cater to them. It would be unwise to place the majority of your money in any one sector, since the demographic changes in society are going to impact every sector, although at different times. For most investors, you would get a piece of nearly every major sector by investing in an S&P 500 Index Fund at a fraction of the cost of investing in a sector fund (see next chapter). If that’s the case, then why invest in a sector fund at all?

Rotation Nastiness: Avoiding the Cinderella Cycles in Sectors

Long-term changes in society and the economy are in progress, although we can’t see them day to day. There are more drugs coming on the market from the biotechnology boom. More housing is being tailored to those who are empty-nesters, nearly retired, fully retired, and disabled. And every industry knows where their customers are coming from and where they are headed. Harry Dent, for example, found that when people hit their peak spending years (typically at age forty-seven), they trigger a boom in all kinds of consumer spending, from appliances to mutual funds. And these consumers indirectly benefit the stock prices of specific companies in sectors where the spending is greatest.

If a diversified mutual fund will give you decent exposure to profit from all of these developments, why concentrate your money on a few dozen companies at a time? The answer is in an obscure phrase mentioned earlier: sector rotation.

When money managers conclude—often in a herdlike fashion—that certain sectors are “overbought” (read: time to take profits and sell), they usually reinvest that money elsewhere. If stocks are generally dour, they buy bonds or sit in cash. Stock-fund managers generally are obligated to find other stocks that are either growing earnings or are bargains (depending on whether they have a growth or value orientation, or both). That’s when they head to a sector where the p/e’s and prices are lower.

Back to the supermarket analogy. If you want peaches and they are sold out, out of season, or selling for $10 a pound, you look at the price of bananas, pears, or apples. The same thing happens in the stock market. During a prolonged sell-off or correction phase, money managers buy stocks with reasonable prices, high probabilities of posting profits, and dividends to boost returns in a sagging market. When technology shares lost their “Cinderella” status in 2000, the big money went over to health-care stocks, snapping up dividend-rich pharmas and some sturdy biotechs. In 2001, when those stocks fell out of favor, some money floated into energy, utilities, and food companies. Then financial services were the favorite sons. And so it goes, with fast money always chasing the highest returns.

Sometimes a sector is only in favor for a few months. Often it’s a few years, which is what happened to technology. Every sector has its day in the sun. Even precious metals, which are lousy investments in a low-inflation environment, shine when there’s a sniff of inflation. Sector rotation is a nasty reality in both the stock and bond markets. Managers are always seeking “quality” (read: a sure way to make money when other sectors aren’t) and will trash one sector to go to another like an angry two-year-old grabbing his marbles and going home.

The most dramatic example of sector rotation was seen in technology stocks. In 1999, technology issues were the best-performing sector, ringing up a 76.9 percent gain. The following year, the tide went out and tech stocks lost 34.1 percent. Cinderella turned into a smashed pumpkin in the course of a year.

The only way not to get hurt by the fickle nastiness of sector rotation and Cinderella cycles is to invest in sectors long term and to diversify as much as possible. It’s okay to concentrate a small portion of your money (not more than 20 percent) on a handful of sectors. You’ll probably do well over time. But you have to stay with it through the down years to reap the benefits of the up years. Sectors in the short term are the riskiest, most volatile forms of investing. Don’t put your money in them unless you have decades to invest your money and you understand that, as a long-term investor, you know that most of the investments within these funds won’t pan out. Fund managers may hit a few winners or have several off years. If you can’t tolerate that kind of risk, don’t even think about sector funds.

Don’t Do What Most People Do: Invest High and Sell Low

This sounds counterintuitive, I know. I’ve done it myself more than once because I wasn’t paying attention to my long-term goals in a fund. Most of the money in sector funds comes in and leaves at the wrong time—consistently. Remember the halcyon years of technology funds, when stocks like Cisco, Microsoft, and Oracle simply couldn’t miss? Let me refresh your memories of the good old days.

During 1998, technology-stock mutual funds soared 53.9 percent. In 1999, they added a heart-pounding 136.6 percent and another 19.1 percent during the first three months of 2001. More than half of the $167 billion in tech funds came in the last six months of the ride of the Valkyries before the gates of Valhalla slammed shut in March 2001. And that’s fairly typical if you look at mutual-fund money flows in previous sector-fund bubbles, notes the Wall Street Journal.

In 1991, health-care and biotech funds were in the spotlight, quadrupling assets after a run-up of 63.8 percent. The performance of these funds was subpar the following year and the hot money fled again. I call this the “bigger jackpot effect,” which I noted in the opening section of my last book, The Kitchen-Table Investor. When the total prize goes up, players think they have a better chance of winning and start playing the game in hordes. It’s a casino mentality. Hot-performing funds rarely have two great years in a row, but the jackpot effect suspends logic. This happens every time a state lottery jackpot goes up. More people play even though the odds of winning are still 10 million to one. The odds of winning don’t recede because more money is in the kitty.

Money that came late to the game in the late ’90s tech run-up mostly bailed when the market turned south and institutional managers sold anything with “technology,” “telecommunications,” or “Internet” in the title. The majority of investors who bought high sold low. The fund companies do everything to encourage this behavior by launching sector funds at the height of a sector’s popularity. So investors buy high and ultimately sell low as a way of cutting their losses, although what they do is guarantee their losses.

Some of the more responsible fund companies add disincentives for selling out of sector funds (“redemptions” in trade paralance), like tagging on additional fees if you sell less than a year after you buy or raising account minimums to $25,000. Still, with nearly four hundred sector funds to choose from, it’s all too tempting to chase last year’s returns in the hot sector du jour.

Another compelling reason to avoid sector funds is that they are expensive to operate and the costs are passed along to you, the shareholder. The annual range of expenses deducted from your assets by management is 0.34 percent to 2.44 percent annually, 1.72 percent being the average. Add to that a sales charge with some funds and you have an expensive enterprise if you are losing money.

I cannot recommend that you put more than 20 percent of your money in a sector fund or hold it for fewer than ten years. If you can’t stay the course to see a trend play out in the marketplace, then stay away from these vehicles. Because you are concentrating your risk in one small part of the world economy, sector funds should only be owned if you have a diversified portfolio across the board: large-cap growth and value; mid- and small-cap growth and value; bonds; real estate; and cash. In the short term they are a form of gambling but if you are serious about holding sector funds long term they are strong investments.

A Cautionary Tale: Mea Culpa

I can attest to the dangers of sector funds because my wife and I succumbed to their deadly charms and lost money over the last few years. Distracted by any number of other things (okay, it’s an excuse), I managed to switch my wife’s SEP-IRA money into health-care and technology sector funds, which I also held in my SEP-IRAs. To compound this crazy antidiversification scheme, I was chasing the technology boom through my 401(k) account, which was 60 percent invested in the technology-crazy Janus Twenty Fund. So we got burned and my wife went nuts every time she got a quarterly statement, so we switched into diversified value and growth funds. I maintain my position in a health-care fund (The Vanguard Health Care Fund), because I’m going to leave it alone in my Roth IRA for the next few decades.

Sector funds have this tendency to show you the possibilities of extreme profits in a narrowly focused portfolio, and then pull the rug from under you just when you’ve made a decision to buy. And there are more cautionary tales out there than mine. In late 2001, the ProFunds Internet Fund was down a numbing 90 percent for the year, followed by the Jacob Internet Fund, which was down 79.4 percent. And these funds have plenty of company. Would you feel comfortable looking at your fund statement, knowing that only 10 percent to 20 percent of your money was left? These funds may or may not rebound, but you need to know that they offer no protection when sector rotation turns against you. They are all-or-nothing propositions.

* * *

There’s a fable about all-or-nothingness that I’d like to share with you. A fisherman once lived in a ramshackle cottage by the sea with his wife. He was fishing for days with nothing to show for his time when he felt a tug at his line. When he hauled up the fish, it was a flounder who began to talk to him. “I beg you not to kill me, for I am really an enchanted prince, so please let me go!” The fisherman obliged and returned to his wife to tell her about his incredible day.

“So let me get this straight,” says the wife. “You catch this enchanted talking fish and you don’t even ask for a wish before you throw him back? Get your butt back in that boat. Ask him if he can get us out of this stinking hole and into better digs! Talk to the fish, or I’m out of here.”

The man returned to the sea reluctantly and set his line in the water. After many frustrating hours, he yelled out to the fish to come up, and the fish surfaced.

“Sorry to bother you, prince,” the fisherman said, “but my wife was wondering how she could get a nice house.”

“Go back to your new home,” the fish said, and swam away.

The man went home again, and was astounded to find that in its place was a lovely ranch home with a wide porch, two-car garage, and plenty of storage for his fishing equipment. His wife gave him the tour of the new master bath and bedroom, the powder room, and a kitchen filled with new appliances. After a week, however, the wife grew restless.

“Husband, you know that if the fish can produce a house like this, he can certainly build us a bigger house. This house doesn’t have a basement or a guest room or a place for me to sew and knit. Go back and talk to your fish again, or I will divorce you.”

So once again, the fisherman spent untold hours in the boat until he cried out in frustration to summon the flounder. The fish, upon hearing his wife’s new request, sent the man home again.

In the place of the tidy ranch house was a ten-thousand-square-foot castle with an immense atrium, six bedrooms, a media/recreation room, exercise room/spa, and kitchen with professional-quality appliances. The home also had a five-car garage, koi pond, and a master bathroom that could accommodate a fleet of boats.

The wife was happy for another week, until she started pining for a country club membership, a winter home in Maui, a new wardrobe, a trip around the world, a sports car, SUV, luxury sedan, a boat of her own, a portfolio of technology stocks, and enough money so that she could knock down her new home and build the largest custom home possible.

Shocked at his wife’s avarice, the fisherman reluctantly said he would return to the fish, but was unsure of what the fish would say. An angry storm was raging and the fisherman was unable to put his boat into the boiling waves. He shouted in desperation. The fish floated close to shore and listened to the man once more.

“Now what does she want?” the fish asked derisively.

“She wants to be a master of the universe,” the fisherman said with a mixture of sarcasm and truth.

“Then she shall have her cottage again. Go home, she is waiting for you there.”

Markets have a way of humbling us if we seek too much. There’s nothing wrong with merging our need for growth with a little risk taking, but you have to balance that risk carefully.