Chapter 2

If you follow along up the brook that runs through Mr. Bean’s woods, pretty soon you come to a dirt road that is the boundary of the Bean property. The Big Woods are really a continuation of the Bean Woods on the other side of the road. But as soon as you cross the road into them you feel a difference. No thrushes or pewees sing in the Big Woods; there are none of the rustlings and patterings that tell you of little animals going about their daily business. Except for the chatter of the brook, everything is very still.

Freddy and Theodore went more and more slowly as they approached the road. Freddy’s jog trot slowed to a walk, and Theodore’s long jumps became short hops that even the smallest grasshopper would have been ashamed of. They crossed the road. And under the shadow of the trees on the other side they stopped.

“Well, this is The Big Woods,” said Theodore.

“The Big Woods,” said Freddy, looking around. “The Big Woods. Well, well.” And after a minute he said: “I don’t know how you feel, but I’m sort of tired. Long walk, hot day, and so on. I think I’ll rest a little.” And he sat down at the edge of the road.

Theodore sat down beside him, and they talked for a little while about the weather, and politics, and the coming-out party Charles, the rooster, had given for his youngest daughter, and about everything but the Big Woods. And then Freddy got up.

“Well,” he said, “shall we go back now?”

“Go back!” said the frog. “Why, we haven’t been anywhere yet.”

“We’ve been to the Big Woods,” said Freddy; “And that’s where we said we were going.”

“We’ve been to them, but we haven’t been in them,” said Theodore. “You couldn’t say you’d been to a show if you just went up and looked at the outside of the theatre, could you? Look, Freddy, we ought to explore ’em as long as we’re here. You’re so bub-bub, I mean brave, I thought you’d plunge right into their very depths.”

Freddy shook his head. “I don’t pretend to be brave,” he said modestly.

“Well, you’re not a c-coward, are you?”

“Why no; I don’t think I’m exactly a coward, Theodore.”

“You’ve got to be either one thing or the other,” said the frog. “If you’re not brave, you’re a coward, but if you’re not a coward, then you’re brave. You can’t be both.”

“OK, then I’m brave,” said Freddy. “And where does that get us?”

“It ought to g-get us into the woods,” replied Theodore.

“See here,” said Freddy. “Let’s just admit that we aren’t either of us very brave, and go on back to the pool and be comfortable. Eh?”

But Theodore said no. “I’m not going to come all the way up here for nothing,” he said. “I’m going to prove one thing anyway.” He gathered his hind legs under him and made a long jump that carried him several yards into the woods. “I’m that much braver than you, Freddy.”

Freddy got up. He looked into the dark shadows under the trees. “Oh, dear,” he thought. And then he thought: “I can’t let a frog get the best of me. I may be only a pig, but I’ve got some pride.” And he marched into the woods.

Of course Theodore knew all about Freddy’s career as a detective, and an explorer, and he had always thought of him as one of the most courageous animals alive. And when he discovered that he was just about as courageous himself, it went to his head and he took another jump. For he thought: “My goodness, if I can prove that I am braver than Freddy, I will get a big reputation and be invited to b-banquets and even maybe get my name in the pup-pup, I mean paper.” (You will notice that he had got so used to hearing himself stutter that he even stuttered when he thought.)

But Freddy was not to be outdone. His reputation was at stake, and so he dashed after Theodore. And Theodore jumped again.

So pretty soon it became a race to see who could get farther into the Big Woods and prove himself the braver of the two. They tore on through bushes and over logs and stones and then all at once were stopped short by a thicket of briars and witch-hopple that it was impossible to push through. So they stood for a minute panting and looking at each other.

“My goodness, weren’t we silly!” said Freddy.

“Yes,” said Theodore. “My, isn’t it still!”

“Too still,” said Freddy. “The way it is before a thunderstorm. And every minute you expect it to go flash-bang! And yet you can’t see anything.”

He looked around. “The trouble with woods is, you can’t see anything but trees.”

“I’d rather not see anything else,” said the frog. They were both speaking in undertones. And suddenly Theodore jumped straight up in the air.

“Wow!” he yelled. “What’s that?”

Freddy jumped too, though not so high. “Don’t do that!” he said crossly, as Theodore turned to look intently at the place where he had been standing a second before.

“Sorry,” said the frog. “I d-didn’t realize I was standing on an ant hill. One of ’em walked across my fuf-fuf, I mean foot.”

“Let’s get out of here,” said the pig. “Oh, look! Did—did you see something move down behind that big hemlock? I don’t mind telling you, Theodore, that I’m scared.”

“You don’t have to tell me,” said the frog. “Your tail’s come uncurled. Well, I’m scared too. C-come on.”

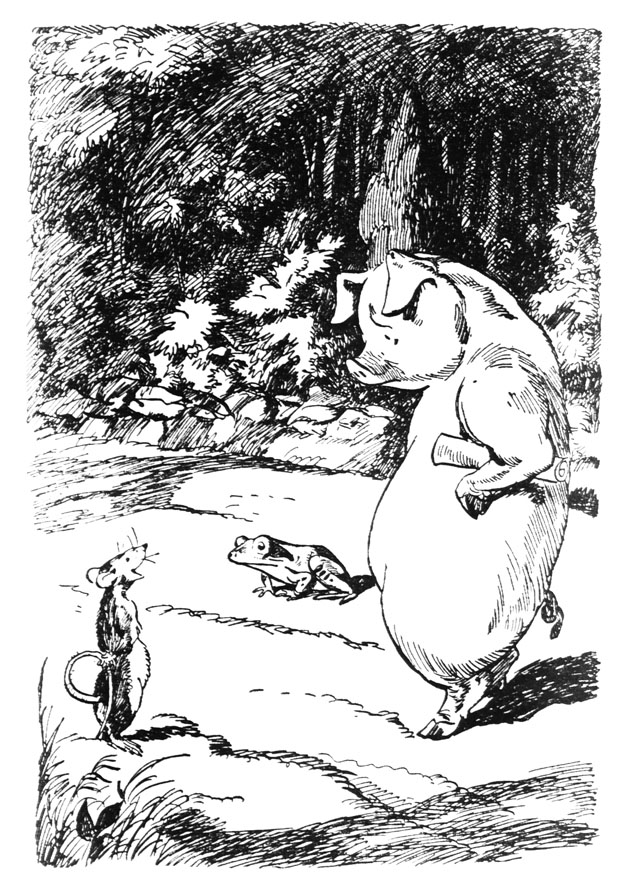

If the race into the woods had been to decide which of them was the braver, the race out was to decide which was the scareder. And it too was a tie. They both reached the road at the same moment. And almost fell over a large grey rat who was plodding along the middle of it.

“Simon!” exclaimed Freddy. “What are you doing here? See here, you’re not living in the neighborhood again, are you?” And he frowned, or at least tried to, for it is pretty hard to frown if you haven’t any eyebrows.

The rat, who had looked startled to see Freddy, recovered himself and smiled an oily smile.

“My old friend, Freddy!” he said. “Dear, dear; what a pleasure to be sure! And how are all those other funny animals? And the good Beans?”

“Dear, dear; what a pleasure!”

“It’s no pleasure to me,” said Freddy shortly. “And I may say that the other animals, and the good Beans, are quite ready to chase you out of the county again, as they did before, if they catch you up to any of your old thieving tricks.”

Simon’s long yellow teeth gleamed wickedly under his twitching whiskers. “Sticks and stones may break my bones, Freddy,” he said, “but hard words cannot hurt me. You always were a big talker, but I can’t remember that you ever did much.” He snickered. “Remember up in the barn that night when you broke your tooth on the toy locomotive?” He turned to Theodore. “Freddy thought it was me he had hold of. Snapped one of his beautiful white teeth right off. We made up a song about it:

Freddy the sleuth,

He busted a tooth—

“That’ll do for you, Simon,” said the pig angrily. “What are you doing here? I thought you’d left the country.”

“I don’t see that it’s any of your business, pig,” said the rat. “This is a public road. I’ve got as good a right here as you. But I don’t mind telling you. I’ve been visiting my relatives out in Iowa. That’s a great place, Freddy. Lots of pigs in Iowa. But they don’t make poetry. No, no. Out in Iowa the pigs make pork. Pork, not poetry, Freddy. You ought to take a little trip out there. Hey, quit!” he squealed, as Freddy made a sudden rush for him.

But Freddy was too exhausted by his gallop through the woods to chase Simon very far. He gave up, and the rat, who had dived into the ditch, climbed back on the road. “Smarty!” he grinned.

“All right, Simon,” said Freddy. “I’ve warned you.”

“Why, so you have, pig,” replied the rat. “So it’s only fair that I should warn you in turn. I judge by the speed with which you came out of the Big Woods, that something was after you. A bit foolhardy to venture in there, weren’t you? When I lived in this neighborhood, I found out some things about the Big Woods that you smart farm animals don’t know. I don’t like you, Freddy, as you may have gathered, but on the other hand, I wouldn’t want to see you eaten up. And so I’m warning you—don’t go into the Big Woods again. The next time he’ll get you.”

“He?” said Theodore. “Who?”

Simon lowered his voice. “Come over here,” he said, crossing to the Beans’ side of the road. “He’s probably listening now, and it’s just as well if he doesn’t hear us talking about him. I can’t tell you much about him, except his name, and that he’s very big and ferocious, and walks very, very quietly. And then, from be hind a tree—pounce! Snip-snap! No more Freddy!”

“Nonsense!” said Freddy. “There’s nothing in there. We didn’t see anything. We-we were just having a race.”

“That’s what I gathered,” said the rat with a snicker. “You were racing him, and you won—this time. Well, I shan’t be able to say, ‘I told you so,’ because when the Ignormus gets you, there won’t be any Freddy to say it to.”

“The what?” asked Theodore.

“The Ignormus,” said Simon. “Well, now I’ve warned you. Good-bye, gentlemen.”

“I don’t like the s-sound of that much,” said Theodore when Simon had gone off down the road.

“Pshaw,” said Freddy, “don’t let that upset you. Simon is the worst liar in three counties. If he tells you anything, you can be pretty sure that the truth is something different. Anyway, Theodore, we have explored the Big Woods.”

“And got g-good and scared,” said the frog. “I guess I was wrong to say that you couldn’t be brave and cowardly at the same tut-tut, I mean time. Because we were brave too, to go in at all.”

“I guess,” said Freddy, “that all brave deeds are like that. Only later, when the people who did them tell about them, they forget the cowardly part. Maybe it would be just as well if we did the same thing. After all, we did go in.—But, my goodness, I must get down to the farm and tell the animals that Simon and his gang are back in the country again. We’ll have to do something about that. Come along, Theodore.”