Chapter 11

As they came down along the stone wall towards the vegetable garden, the two animals suddenly stopped and crouched down. For among the cabbages two white ears were sticking up, where no ears ought to be. And there was a decided ripple among the beet tops, although there was no wind. Also, the small dark figure of some animal was being very busy among the onions.

“My goodness,” whispered Freddy, “if Mr. Bean saw this he’d be wild! What’s got into all these animals anyway? They know perfectly well they’re never allowed in the vegetable garden.”

“Let me sneak in and grab one,” said Jinx. “We’ll soon find out.”

So he got down close to the ground and crept silently in between the bean rows and disappeared. There was a squeak and a flurry among the onions, and after a minute Jinx came out, carrying a very small and very terrified squirrel by the nape of the neck. He set him down in front of Freddy.

“Well, young man,” said the pig severely, “can you give me some explanation of your strange and reprehensible actions?”

“Yes, sir,” stammered the squirrel. “I mean, no, sir. My actions are not rep—what you said. I was just—sort of—looking around.”

Freddy bent down and sniffed. “As I thought,” he said. “You’ve been eating onions. Mr. Bean’s onions,” he added more sternly. “Mr. Bean’s best onions,” he shouted suddenly.

The squirrel cowered. “Oh no, sir,” he whimpered. “I didn’t eat any. I just—well, sort of pulled one up. To see how they grow. I—I’m interested in how things grow,” he added.

“Indeed!” said Freddy. “Interested in how things grow, eh? I suppose you never thought how the onion feels about it—being pulled up by the roots, just so someone could see how it grows? Pretty callous, you are, for such a young one.”

“And, oh boy, will Mr. Bean pull you up by the roots when he hears of this,” put in Jinx.

“Unless, of course,” said Freddy, “you had some good reason.”

“Oh, I did,” said the squirrel. “But I can’t tell you. My mother—”

“I expect she got a note this morning,” interrupted the pig. “From someone we don’t talk about much. Eh? Was that it?”

“Oh, sir, then you know about it! Yes, she—But I mustn’t tell anybody, mother says.”

So they went to see the squirrel’s mother. It was as Freddy had suspected: she had received a demand from the Ignormus. One dozen large onions to be laid under the third tree from the left of the bridge, or he’d eat her family all up.

“This is serious,” said Freddy. “The Ignormus (if there is an Ignormus) must have written at least a dozen such notes from the look of things. Tell you what we’ll have to do. We’ll hide under the bridge tonight and watch. He’ll have to come for all these vegetables before they get wilted. Then if he’s what I suspect: a small animal with white tail and whiskers, we’ll pounce on him and capture him. And if he’s really a big animal with horns and claws—”

“He’ll pounce on us,” said Jinx. “That’s a swell idea, Freddy.”

“We’ll just stay hidden,” said Freddy. “There’s no danger—or not much. Come on, Jinx. You know there’s none of the other animals that I can ask, the way they all feel about me now. Look, Jinx. I’ve done things for you. Remember the time your head got caught in the cream bottle, and I got you out before Mrs. Bean found you? Remember—”

“O.K., O.K.,” said the cat. “You’ll have me crying in a minute. I’ll go. But I’m not going for old friendship’s sake; I’m going because I know if there was very much danger you’d be eight miles from that bridge tonight. If I’m not braver than you, pig, I’ll eat my own tail.”

“I’d like to see you try it,” said Freddy, who was always interested in such speculations. “You know, I wonder: if you started eating your own tail, and went right on eating—hind legs, body, fore legs—you’d finally eat up your own head, wouldn’t you?”

“Try that one on the Ignormus,” said Jinx. “Come on, we’ve got to get those carrots for Mrs. Winnick.”

Ordinarily it would have been easy enough to steal a dozen carrots from the vegetable garden. But today there were so many thieves of various shapes and sizes frantically pulling up radishes and picking beans and peas that they kept getting into one another’s way, and although they all pretended not to see one another, for a pig of Freddy’s position and standing in the community to join openly in such wholesale robbery was out of the question.

“The Ignormus must have a tremendous appetite,” he said.

“He must have written a lot of letters last night,” said Jinx. “Guess I’ll go up to the Big Woods and see if he doesn’t want to hire me as his secretary. But this isn’t getting us any carrots. Here, I’ll fix it.” And he jumped up on the wall and shouted: “Look out! Look out! Here comes Mr. Bean!”

There was a great squeaking and scampering, and in half a minute the vegetable garden was as empty of animal life as the Big Woods themselves. And Jinx and Freddy went in and pulled up a dozen prime carrots without anyone seeing them.

It was fairly late in the afternoon before they finally got them up through the woods and under the bridge. They had had to hide them in the grass until Freddy could bring a paper bag from his library to put them in, and on the way up to the woods they were stopped a dozen times by inquisitive friends who wanted to know what they were carrying. But they got them there at last, and then settled down in a clump of bushes a little way up the road where they could see who came for them.

They had been there about half an hour when they found they were both getting very sleepy.

“Ho, hum!” yawned Freddy. “We simply mustn’t go to sleep, Jinx. We may have to wait here half the night, and it isn’t even dark yet. How would it be,” he said brightly, “if I was to recite some of my poetry to you?”

“You can try it,” said the cat doubtfully. “But you know, to me poetry—well, it’s like sitting in a car and watching the telegraph poles go by. The rhymes go by—heart, dart; love, dove—just like the poles. And I don’t know what it is—they send me right off. Now if you had some poetry that didn’t rhyme—”

“But then it wouldn’t be poetry,” Freddy objected.

“O.K.,” said the cat. “I’m just telling you. Goodness knows I’m no authority on poetry. I’m a great authority on sleep, though. Sleep; now that’s my subject. I’ve studied it from every angle. Boy, how I’ve studied sleep! And you know, I feel a study period coming on right now.” And he began to purr and closed his eyes.

“No, no,” said Freddy. “We mustn’t. Listen, Jinx; let me just recite the B verse from my alphabet poem. I’d like your opinion of it. You see, first I say: ‘Bees, bothered by bold bears, behave badly.’ And the verse goes like this.

“Your honey or your life!” says the bold burglar bear,

As he climbs up the tree where the bees have their lair.

“Burglars! Burglars!” The tree begins to hum.

“Sharpen up your stings, brothers! Tighten up your wings, brothers!

“Beat the alarm on the big bass drum!

“Watch yourself, bear, for

here

we

come!”

Then the big black bees buzz out from their lair.

With sharp stings ready zoom down on the bear.

“Ouch! Ouch! Ouch! Don’t be so rough!”

He slithers down the tree, squalling, “Hey, let me be!” Bawling

“Keep your old honey. Horrid sticky stuff!

“I’m going home, for

I’ve

Had

enough!”

Although he made many very appropriate gestures when he recited, Freddy always tilted his head back and shut his eyes. He said it made him put more feeling into it. When he had finished and opened his eyes, he saw that the cat was sound asleep.

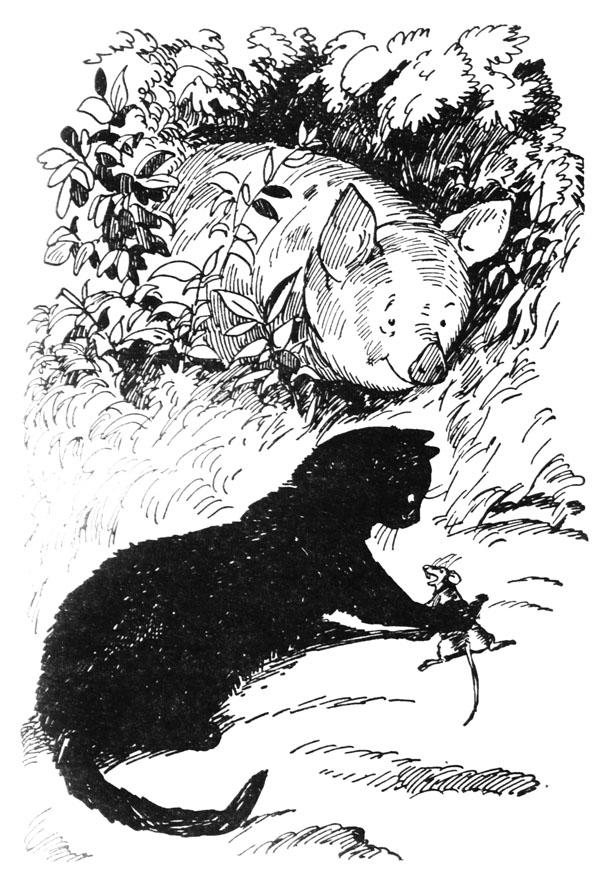

“Well of all the—” he began angrily, and suddenly stopped, for he saw something moving down the road. He waked up Jinx quietly, and the two watched as a small grey animal came slowly along towards them, stopping every now and then to sniff the air suspiciously.

“By gum, it’s Simon!” said the cat suddenly. With one leap he was out on the road, and before the rat could scuttle off into the bushes Jinx had him.

Simon knew better than to struggle. He knew that the sharp claws that were just barely pricking his back would dig deeper if he didn’t lie still.

“Well, well,” he said with a malicious smile, “my old friend the mouse-chaser! Quite a surprise! Turned hold-up man, now, eh? Molesting unprotected and innocent citizens on the public roads. Well, I’m not surprised. You always had the makings of a gangster in you, Jinx.”

“Better be polite, rat,” said Jinx, “or I’ll tickle you. Like this.” And he wiggled his claws gently.

The rat squirmed. “You let me alone,” he squeaked. “What right have you got to pick on me? This road isn’t on old Bean’s property. I’m going along minding my own business. You mind yours.”

“You let me alone,” he squeaked.

“Your business is our business, Simon, old shifty-eye,” said Jinx.

“It’s funny,” said Freddy, “that I’ve only been up here a few times, and yet twice I’ve seen you on the road. Last time you’d been visiting your relatives in Iowa. What is it this time?”

But instead of answering, Simon burst into shrieks of hysterical laughter as he wriggled and twisted in the effort to get away from Jinx, who hadn’t been able to resist the temptation to tickle him again.

“Let him alone, Jinx,” said Freddy. “I want him to talk, not yell in that undignified way.”

So when Jinx had released him, Simon sat up, and said: “I don’t know why you’ve got any more right to ask me what I’m doing here than I have to ask you. However, since you’re so interested, there is no reason why I shouldn’t be perfectly frank.”

“Oh-oh,” said Jinx, “look out for a bigger one than usual.”

Simon grinned maliciously at the cat. “I would scarcely expect you to believe me,” he said. “People that tell lies all the time themselves don’t know the truth when they hear it. But I will tell you, Freddy, that the reason you see me in this neighborhood again is that I am on my way to visit my son, Ezra, who lives over beyond Centerboro.”

“You’re a great family for visiting,” said Jinx, “though why any of you ever want to see any of the others beats me. You aren’t handsome, you aren’t honest, you aren’t even very good company—”

“Spare me your compliments,” said Simon. “And if there’s nothing else you want to know, will you allow me to continue my journey? It is getting dark, and personally I would like to be as far from the Big Woods before nightfall as possible. I haven’t asked you what you are doing here, but I will tell you one thing you’re doing: you’re taking chances that I wouldn’t care to take. However, I warned you before. and if you choose to ignore my warning, it’s you that will be clawed to pieces—not me. Good evening, gentlemen.”

He spoke the last word so sarcastically that Jinx moved towards him again, but Freddy held the cat back. “Let him go,” he said.

“But I want to tickle him again,” the cat pleaded. “He makes such funny noises.”

But Freddy wouldn’t let him, and the rat scuttled off down the road.

“I don’t like Simon being around here so much,” said Freddy. “He may be telling the truth, of course. But if he and his family are planning to come back here to live, we’re going to have more trouble on our hands.”

“Well, they certainly aren’t living anywhere around here now,” said Jinx. “A family of rats can’t live in a neighborhood without somebody seeing them, and nobody’s seen anything of them except you, these two times on the road.”

“I guess you’re right,” said the pig. “It’s when they get settled in as they did in Mr. Bean’s barn, with runways and passages and front doors and back doors and secret entrances that they’re hard to get rid of. And we’d stop them doing that another time. Gosh, we’ve got trouble enough with this Ignormus (if there is an Ignormus), without having rats around. Come on, let’s get back in our hiding place.”

They found that after the encounter with Simon they weren’t sleepy any more, and they watched the sun down and the moon up, and they watched the moon swing across the sky and follow the sun down, but still nothing stirred, and no Ignormus came to call for the carrots and other vegetables. At last about three, in the morning Jinx got up and stretched.

“Guess those notes were somebody’s idea of a joke,” he said. “If the Ignormus was coming, he’d have come by this time.”

“Whoever wrote those notes wrote the one I found in the Grimby house,” said Freddy. “And that wasn’t a joke. No sir; the Ignormus (if there is an Ignormus) wrote them, and—”

“Why do you keep saying: if there is an Ignormus?” cut in Jinx irritably.

“Because I don’t really believe there is.”

“Yeah?” said the cat. “And so you come up here to watch all night for him! Well, if he doesn’t exist, then we’ve seen him, we’ve seen what you expected to see, so let’s go home.” And he walked out of the hiding place.

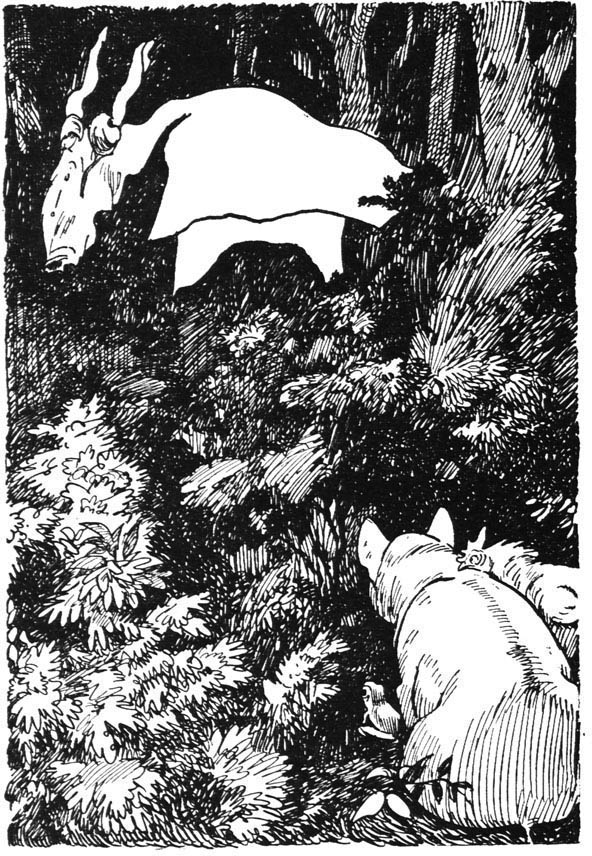

Freddy followed more slowly. And suddenly both animals looked up at a slight noise in the treetops on the Big Woods side of the road, and then with a terrified yell leaped the ditch and dove into the underbrush. For floating down silently like an enormous owl was a great white shape that hovered over them and seemed about to drop and seize them. In a last horrified glance over their shoulders, they saw on the front end of the creature a sort of head, with what looked like two long white horns. And then they were galloping and stumbling and tripping and panting their way down through the woods to safety.

… floating down silently … was a great white shape

“So he doesn’t exist, hey?” said Jinx, when they had at last thrown themselves down on the grass by the brook and had caught their breath. “Or else he’s a little animal with white whiskers. Huh! I suppose you’ll tell me that was a shadow or a cloud, or maybe Hank learning to fly.”

“No, it was something, all right,” said Freddy.

“Something I don’t have to get any better acquainted with,” replied the cat. “Flying elephants are out of my line. I’m going home.”

“Well, I’m not,” said Freddy firmly. “Mr. Bean thinks I’m a thief, and all the animals are mad at me because I haven’t done anything about the Ignormus (if there is—)” he stopped. “Well, it looks as if there was one, after all. Anyway, I’m not coming home until I’ve solved this case. Either,” he said dramatically—“either I bring home the white hide of that Ignormus and nail it on the barn door, or you will never see your old Freddy again.”

“Uh-huh,” said Jinx, who was never much impressed by speeches of this kind. “Well, don’t let him get your hide. And if you want help, you know where to find me. So long.”

When Jinx had gone, Freddy sat and thought for a while. And this time he didn’t go to sleep. Never, in any of his detective cases, had he met so many reverses, or been so baffled. And the animals were beginning to mistrust his ability. If he failed now he would never be Freddy, the great detective any more; he would be just Freddy—a pig. He got up and walked slowly in the growing light of dawn towards the Big Woods.