![]()

Treacherous Shortcuts in Decision Making

WHICH IS THE more likely cause of death, being attacked and killed by a shark or getting struck by falling airplane parts?1 Most people don’t have any experience of either, fortunately, but when asked this question they more often than not decide that the shark is the more likely culprit. That’s wrong, however. In the United States, death from falling airplane parts is actually thirty times as probable as dying from a shark attack.2

What’s going on here? Shark attacks, no matter how rare, receive considerable media attention and are horrifically easy to imagine, especially if you’ve seen the classic movie Jaws.3 But can you recall a media report about falling airplane parts? If any graphic images come to mind, it’s likely to be a plane in a cartoon humorously coming apart à la Bugs Bunny. We just don’t think about small pieces of airplanes coming off. The images we generally have for airplane failure are of a catastrophic crash that kills passengers rather than anyone on the ground. Lacking firsthand experience of seeing airplane parts falling out of the sky and never having read about the problem, we mentally choose the more available image of shark mayhem as the more likely event.

This is an example of the availability heuristic, which leads us to subconsciously give more weight to images that come readily to mind than those that are “fuzzier” to recall.4 Next, let’s look more closely at cognitive heuristics.

Beginning in the 1970s, researchers began discovering that people adopt an extensive number of such mental shortcuts, or rules of thumb, to make a wide range of day-to-day decisions rather than formally calculating the actual odds of a given outcome. The pioneering work was done by Daniel Kahneman, now of Princeton, and the late Amos Tversky of Stanford. As noted, Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 for this work. Tversky would undoubtedly have shared the prize, the recipients of which must be living, had he not died prematurely several years earlier.*8 These judgmental heuristics or cognitive heuristics are simplifying strategies we use for managing large amounts of information. They seem to be hardwired into our minds and are thus rather undetectable under ordinary circumstances. Most of us are entirely unaware of them, especially in the heat of action.

Having evolved out of long human experience, these judgmental shortcuts work exceptionally well most of the time, as does the emotional decision making of Affect, and are enormous time-savers.

Consider, for example, what happens as you drive a car down a highway. You concentrate on dozens of mental shortcuts not only to operate the car but also to monitor highway traffic, road signs, and the visibility ahead, as well as the vehicles around you, all the while staying mostly undistracted by the music playing on your iPod and screening out thousands of other distracting and disruptive bits of information. That you can actually do this “almost without thinking” is a tribute to the efficiency of our mental heuristics.

We use such heuristics in dealing with many of our decisions and judgments and tend to become “intuitive statisticians” in the process. We think, for example, that our odds of survival in a crash are better when we are driving at fifty-five miles an hour than at ninety miles an hour, although few of us have ever bothered to check the actual numbers. We readily assess that a professional team is likely to beat an amateur one, assuming that the “amateurs” are not of Olympic quality. And we might expect to get to a city three hundred miles away faster by air than by ground.*9

We have an immediate sense of the odds in such situations (or we think we do), using our past experiences to make these assessments quickly. Hundreds of times a day, these heuristics work flawlessly for us.

However, being an “intuitive statistician” has limitations as well as advantages. The simplifying processes that are normally efficient time-savers also lead to systematic mistakes in decision making. Despite what many economists and financial theorists assume, people are not really good intuitive statisticians, and as a result, heuristics are consistently shortchanging investors, even professionals. If I had to pinpoint the one primary error that heuristics cause investors to make, it would be this: they do not calculate odds properly when making investment decisions. The distortions produced by our heuristic calculations are often large and systematic, leading even the savviest investors into blunders of considerable magnitude. In addition, these cognitive biases are locked more firmly into place by group pressures.5 Our own biases are reinforced by the powerful influence of experts and peer groups we respect, and the pressure for us to follow becomes more compelling.

The research also indicates that even when people are warned of such biases, they appear not to be able to adjust for the effects. So it will take a good deal of concentration and effort on your part to avoid these pitfalls. Doing so begins with becoming familiar with these heuristics. Once their nature is understood, a set of rules can be developed to help monitor your decisions and provide a shield against serious mishaps—perhaps even profit from them instead. But as you’ll see, it’s much easier said than done, even after people have been made fully aware of them.

Let’s start by taking a closer look at the availability heuristic. According to Tversky and Kahneman, it causes us to “assess the frequency of a class or the probability of an event by the ease with which instances or occurrences can be brought to mind.”6 This is why we think deaths by shark attack are more common than deaths from pieces of airplanes falling on people.

The shortcut answers we get this way are accurate most of the time because our minds normally recall most readily events that have occurred frequently. But they can sometimes be strikingly off the mark. We think something is more likely because the prospect is more available in our minds when an event had an especially important meaning—in other words, it had a big impact on our thinking—and had occurred recently.7 There are two psychological errors involved here. The first of these errors is referred to in the literature as “saliency” and the second as “recency.” Saliency leads people to recall distinctly “good” events (or “bad” events) disproportionally to the actual frequency. It’s so automatic that we barely recognize that we’re doing it.8 For example, returning to the wilds of nature, the actual chance of being mauled by a grizzly bear at a national park is one or two per million visitors; the death rate is even lower. Casualties from shark attacks are an even smaller percentage of all deaths of swimmers in coastal waters. But because the saliency of an actual attack is so powerful, we wind up thinking such attacks happen more often than they really do. Our memories are heuristically biased to bring scary images to mind more quickly.

I was snorkeling alone in the Bahamas’ Exuma National Park several years back, well aware, in the abstract, that the probability of a shark attack was slim. Then a six-hundred-pound bull shark slowly came swimming toward me. As the dorsal fin passed by me inches away, it appeared to have the width of a nuclear submarine. I hoped it knew how unlikely it was to attack as I did. When the shark stopped behind me, my evaluation of attack probabilities skewed sharply higher. Fortunately, the shark didn’t have a taste for snorkeler that day—but I was left with a considerable emotional charge that skewed my own calculations of shark attacks for some time to come.

To see recency in action, consider that after disasters, such as floods and earthquakes, purchases of flood and earthquake insurance rise, even though the underlying likelihood of floods and earthquakes hasn’t changed. People are led to think these disasters are more likely because they’ve happened recently.9 Through such subsconscious mechanisms, recent, salient events often strongly influence decision making in the stock and bond markets that can cause or exacerbate sharp price movements.

One key way in which this occurs is that the recent trend is thought to be the new permanent trend. Take the market when the base rate, meaning the long-term rate of returns of stocks, is trampled under by the case rate, the more recent short-term but sharply higher rate of return stocks are currently generating.*10 Even though we know that the case rate in most instances does not last and reverts back to the base rate, whether for a stock, a group of stocks, or an industry, our minds cling to a false hope that it won’t be so this time. Recency frequently convinces us that the case rate is now the new base rate.

Consider a recent example. Bill Gross, the outstanding head of PIMCO, the largest bond house in the world, and Mohamed El-Erian, its CEO, coined the term “the New Normal” as the economy was put through the shredder in 2007 and 2008. The New Normal anticipated that low earnings and stock prices would be the norm for years into the future because the growth rate of the global economy was altered downward permanently. This chant was widely picked up by both money managers and the media and became the prevailing wisdom about stocks for more than two years.

But the stock market, in its contrarian way, completely ignored the doddering role it was assigned by the experts and started to rally. It had risen more than 100 percent by mid-2011 from its New Normal lows of March 2009. After the market doubled, the New Normal lost much of its luster. This has happened in similar circumstances in the past. Recall the New Era of the 1920s, when stocks roared, or the New Economy during the Internet bubble. I expect we’ve not heard the last of such clever coinages.

Now consider an even more glaring example. Conventional financial thinking holds that IPOs should be offered at a small discount to its actual value (in the neighborhood of around 10 percent), to ensure that the issue is fully subscribed for.

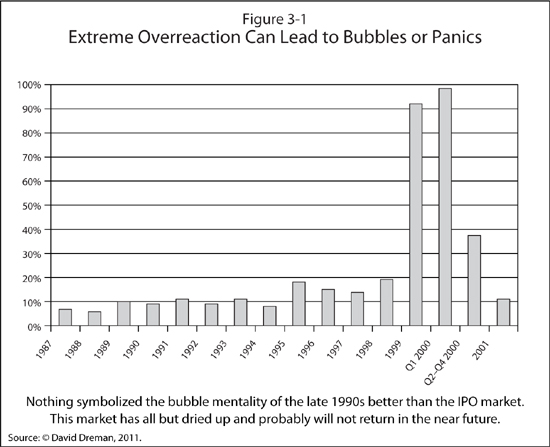

Figure 3-1 demonstrates the large overpricing of IPOs during the 1996–March 2000 Internet bubble. As the figure indicates, the average IPO was priced at a small premium of 10 percent or less at the first day’s closing price for the eight years from 1987 through 1994. Over the next four years, premiums expanded significantly, averaging somewhat under 20 percent. Returns of 20 percent in a day are very rare. This major appreciation was by itself enough to attract many investors away from more conventional investments into the far more speculative arena of IPOs. Speculation took over in 1999 and the first three months of 2000, with the average IPO premium rising to a staggering 90 percent, respectively, at the close of the first day’s trading. (For those unfamiliar with initial public offerings, this meant that if you were lucky enough to get an IPO at its issue price, you made 90 to 95 percent on average on your investment by the close of the first day of trading.) Moreover, for the first three months of 2000, the peak of the bubble, the average closing price on IPOs of dot-com stocks (not shown in the figure) increased to 135 percent from the original offering price to the close of the first day’s trading. IPO valuation premiums thus multiplied ten times or more above the normal premiums over the course of the Internet bubble. The recency and saliency of the enormous price movements resulted in investors vividly recalling the sharp gains these stocks provided while downplaying their considerable risks.

A retrospective analysis indicated that the quality of this group of IPOs was certainly no better and, judging by the high rate of company failures, probably a good deal worse than IPOs of earlier time periods.

Since the 1960s, as chapter 1 documented, four major technology bubbles have occurred, with the 1996–2000 mania surpassing any in the past in terms of its size, the enormous appreciation, and the magnitude of the eventual crash.

In the bubble of the early 1980s, for example, the Value Line New Issue Survey analyzed a group of proposed IPOs and found that many were start-ups, perhaps 95 percent dream and 5 percent product. The survey also found that quite a few had only one or two full-time employees and some had none. The majority attempted to go public with absolutely no earnings at 20 to 100 times their book value prior to the offering.10

In 1994, Professors Jay Ritter of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Tim Loughran of the University of Iowa, two of the pioneers in the field of behavioral finance, completed the most comprehensive study of new issues made to date. The study followed the returns of 4,753 IPOs traded on the New York Stock Exchange, the AMEX, and NASDAQ between 1970 and 1990.11 The average return for IPOs was 5 percent annually, compared with 10.8 percent for the S&P 500. Put another way, investing in the S&P 500 over those twenty-one years would have returned 762 percent versus 179 percent for the IPOs. The far safer stocks of the S&P did more than four times as well!

But perhaps even more telling was that the median five-year return for these almost five thousand initial public offerings was a decline of 39 percent from the original offering price. If an investor couldn’t buy the handful of red-hot IPOs that doubled or even tripled on the first trade—and nobody but the largest money managers, hedge funds, mutual funds, and other major investors could—he would lose a good chunk of his original investment.

As in the case of the Value Line study, Loughran and Ritter’s results indicate that many IPOs were start-ups, usually high on expectations and low or nonexistent on actual revenues and earnings. They also found that most new issues go public near the top of an IPO market, when the demand is the greatest and the value of the merchandise is at its lowest. Not coincidentally, it is precisely at this time that investors are most excited about stocks with supposedly excellent visibility—further evidence of the strength of recency and saliency.

A 1991 study by Ritter12 showed that fully 61 percent of IPOs went public in 1983, the peak of the 1977–1983 mania. How many went public in the first five years, when the quality was at its best? Only 6 percent.

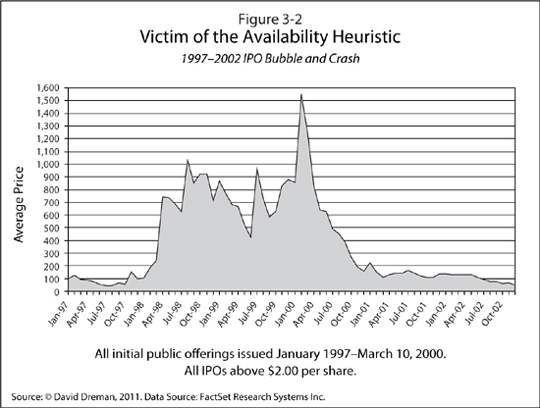

A 2011 working paper by Vladimira Ilieva, of the Dreman Foundation, and myself calculated the price of 1,547 IPOs ($2.00 or more in price) that went public between January 1, 1997, near the beginning of the dot-com bubble, and March 10, 2000, its high point. We then measured the drop from the market high to the low price of each issue through December 31, 2002. As Figure 3-2 shows, the average decline from the high to the low price in the dot-com bubble was a startling 97 percent.13 Finally, the median decline from the IPO offering price was 73 percent higher than the median decline that Ritter and Loughran calculated in this far more severe crash.

Also of interest was that the quality of the IPOs was consistently bad. Of the 1,547 companies in our original sample, only 524 were still listed in mid-2011. The other 66 percent had merged or just plain gone out of business.

Including the work of Ritter and Loughran, we now have an over-forty-year record of how dismal investing in IPOs has actually been. Recency and saliency appear to have played a not-insignificant hand in these results. Other studies support the findings. H. Nejat Seyhun reported that the market beat a sample of 2,298 IPOs for six years,14 and Mario Levis showed that a group of British IPOs underperformed the U.K. averages for three years.15 Further research found that IPO fundamentals fell after the offerings, indicating a deteriorating business picture precisely when investors were most excited by the stock.16

Loughran and Ritter (1995) concluded, “Our evidence is consistent with a market where firms take advantage of transitory windows of opportunity by issuing equity when, on average, they are substantially overvalued.”17 That’s a gentlemanly way of stating that the real mountains of gold were made not by the investors but by the concept weavers, aka the investment bankers, as they were in bubbles hundreds of years back. It seems the investment bankers have known about heuristical errors for centuries and made very good money exploiting them—too good to want to give their discovery to investors or science.

The strength of the subconscious effect of recent and salient events cannot be exaggerated, as the research above indicates. Whether the pain of the 1996–2000 dot-com bubble takes another few years to forget or not, there is little doubt that a new and powerful IPO bubble is out there with results as predictable as any witnessed in this section. Another Psychological Guideline should prove helpful here.

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 2(a): Don’t rely solely on the “case rate.” Take into account the “base rate,” the prior probabilities of profit or loss. Long-term returns of stocks (the “base rate”) are far more likely to be reestablished.

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 2(b): Don’t be seduced by recent rates of return (the “case rate”) for individual stocks or the market when they deviate sharply from past norms. If returns are particularly high or low, they are likely to be abnormal.

In the preceding chapter I spent a fair amount of time detailing the power of Affect in manias and crashes. In the current chapter I have so far detailed the errors that can result from indiscriminately following the availability heuristic lures of recency and saliency. Now, someone may ask, how can all three be present in the same bubble or any other investor error? This question brings us close to the state-of-the-art research cognitive psychologists are currently undertaking.

Affect, although not discovered until much later than cognitive heuristics, is considered by many senior researchers to be the driving force behind price movements. But to try to give a more precise answer about the contributions of recency, saliency, and Affect at this time would be like getting us into the famous (and endless) Abbott and Costello skit “Who’s on First?” But whatever the relative contributions, we receive strong warnings of imminent danger ahead that we can easily pick up.

Although the final research on the contribution of each of these heuristics may take many years to resolve, by now having a knowledge of each, we can build defenses so we can recognize bubbles and get out while there is still time. Naturally, a similar approach could be adapted if stocks dropped to levels that were far too cheap.

The best defense against recency and saliency, in particular, is to keep your eye on the longer term. Though there is certainly no assured way to put recent or memorable experiences into absolute perspective, it might be helpful during periods of extreme pessimism or optimism to wander back to your library. If the market is tanking, reread the financial periodicals from the last major break. If you can, look up The Wall Street Journal of late February 2009, turn to the market section, and read the wailing and sighing by expert after expert, just before the market began one of its sharpest recoveries in history. Similarly, when we have another speculative market, it would not be a bad idea to check the Journal again and read the comments made during the 1996–2000 or 2005–2006 bubble. Though rereading the daily press is not a magic elixir, I think it can help.

I will also point out some defensive tips that should help. By themselves, these tips are not going to put your investing strategy on a firm footing. But you may want to add them to the strategies we are going to discuss later. Think of them as useful personal sidearms until we can bring in the heavy artillery, which will defend you from the heuristics we have discussed.

The second important cognitive bias that Professors Kahneman and Tversky identified was the one they labeled “representativeness.” What they showed in rigorous experimental studies is that it’s a natural human tendency to draw analogies and see identical situations—where none exist.

In the market, representativeness might take the form of labeling two companies or two market environments as the same when the actual resemblance is superficial.18 Give people a little information, and click! they pull out a mental picture they’re familiar with, though it may only remotely represent the truth. The two key ways the representativeness bias leads to miscalculations are that it causes us to give too much emphasis to the similarities between events and does not take into account the actual probability that an event will occur, and that it reduces the importance we give to variables that are actually critical in determining an event’s probability.

An example is the aftermath of the 1987 crash. In four trading days the Dow fell 769 points, culminating with the 508-point decline on Black Monday, October 19, 1987. This wiped out almost $1 trillion worth of value. “Is This 1929?” asked the media in bold headlines. Many investors, taking this heuristic shortcut, fled to cash, caught up in a false parallel.

At the time the situations seemed eerily similar. We had not had a stock market crash for fifty-eight years. Generations grew up believing that because a depression had followed the 1929 crash it would always happen this way. A large part of Wall Street’s experts, the media, and the investing public agreed. Overlooked was the fact that the two crashes had only the remotest similarity. To start with, 1929 was a special case. The nation had numerous panics and crashes in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, without a depression. Crashes or no, the U.S. economy has always bounced back in short order. So crash and depression are not synonymous.

More important, it was apparent even in the spring of 1988 that the economic and investment climate was entirely different. My Forbes column of May 2, 1988, noted some of the differences clearly visible at the time. The column stated that although market savants and the media were presenting charts showing the breathtaking similarity of the market postcrash stock movements after 1987 to those of 1929, there was far less to it than met the eye. In 1929, the market rallied smartly after the debacle before beginning a free fall in the spring of 1930, and many experts believed that history would repeat itself fifty-eight years later. However, a chart, unlike a picture, is not always worth a thousand words; sometimes it is just downright misleading.

Bottom line: the economic and investment fundamentals of 1988 were worlds apart from those of 1930. After the 1987 crash, the economy was rolling along at a rate above most estimates precrash and sharply above the recession levels forecasted postcrash, accompanied by earnings far higher than projected in the weeks following the October 19 debacle. The P/E of the S&P 500 was a little over 13 times earnings, down sharply from 20 times just prior to the crash and below the long-term average of 15 to 16. The situation was diametrically different from that after the crash of 1929. Back then, corporate earnings, along with the financial system, collapsed, and unemployment soared.

Thus 1987 was certainly not 1929, and investors who succumbed to the representativeness bias missed an enormous buying opportunity; by July 1997, the market had quadrupled from its low.

A more recent example of the bias at work is the pricing of oil and commodities in the 2007–2008 crash and the early part of the Great Recession through 2010. Since 1992, oil prices have risen fairly steadily, from $20 a barrel to $100 in early 2008. The fundamentals for oil were very sound. World demand had outstripped new supply every year from 1982 through 2007. Even after the economy began to fall apart in late 2008, the demand for oil dropped only 1.1 percent in 2009. Moreover, the cost of finding oil was going up sharply, and the discovery of vast new fields was a dream of the past. The last million-barrels-a-day oil field was found in the late 1970s. Too, with the dramatic industrialization of China, along with that of other underdeveloped economies in the Far East and elsewhere, demand for oil expanded rapidly.

The price of oil shot upward, breaking $100 a barrel in early 2008, and continued its sharp increase, reaching $145 a barrel by mid-2008. Investors were desperately selling financial assets other than government bonds and piling into oil and other commodities through 2007 to the spring of 2008. Then panic took over. Untold numbers of comparisons between the 2008–2009 economy and that of the Great Depression were made. Nothing was safe, not even oil, regardless of its fundamentals. Within months, oil plummeted from its then high of $145 dollars a barrel to $35, a drop of 76 percent. The price of oil had fallen well below the cost of new discoveries. As markets calmed by mid-2009, oil began to rise again; it reached $95 a barrel by June 2011, approximately 170 percent above its low.

You can see how the effects of cognitive biases combine with those of Affect in this case. The fear of losses contributed to people’s putting undue weight on the supposed similarity in the collapse of the oil price between 2008 and the free fall of stock prices after 1929 and failing to rationally recalculate that the demand for oil had actually dropped very modestly and usage would climb significantly with even a moderate economic recovery. When such emotion is mixed with the effects of our biases, it’s the equivalent of nuclear fusion in the marketplace.

Was it possible to detect that some stocks and commodities were sharply undervalued, just as we saw they were greatly overvalued during the 1996–2000 bubble? My answer is yes. I wrote a column in early June 2009 stating that oil was enormously undervalued for the reasons noted above.19 Oil was then trading around $68 and appreciating about 40 percent from then to June 2011.

The representativeness heuristic can apply just as forcefully to a company or an industry as to the market as a whole. In 2007–2008, many stocks in a number of excellent industries were swept away by the powerful tides that panicked many people. Not only was the sky falling for banks and financial stocks, but many investors calculated that it was also likely to obliterate very strong industrials with worldwide demand for their products, such as Eaton Corporation and Emerson Electric, which dropped 69 percent and 56 percent, respectively, from their late-2007 highs. As the panic worsened, the more analytic investors sold in droves, too. The prevailing fear was that those companies and myriads of others would show minimal earnings for a decade and that many wouldn’t survive at all.

By early March 2009, those dire predictions were seen as a lot of hogwash. Eaton and Emerson would rise 265 percent and 142 percent, respectively, by the end of June 2011, and dozens of more cyclical industries, from heavy equipment to mining to oil drilling, had similar bounce backs. Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold shot up 315 percent and United Technologies Corporation 149 percent through the end of June 2011. That was the reality.

Awareness of the representativeness bias leads to another helpful Psychological Guideline:

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 3: Look beyond obvious similarities between a current investment situation and one that appears similar in the past. Consider other important factors that may result in a markedly different outcome.

A particular flaw in thinking that falls under the rubric of representativeness is what Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman called the “law of small numbers.”20 Examining journals in psychology and education, they found that researchers systematically overstated the importance of findings taken from small samples. The statistically valid “law of large numbers” states that large samples will usually be highly representative of the population from which they are drawn; for example, public opinion polls are fairly accurate because they draw on large and representative groups. The smaller the sample used, however (or the shorter the record), the more likely the findings are to be chance rather than meaningful.

Yet the Tversky and Kahneman study showed that psychological or educational experimenters typically premise their research theories on samples so small that the results have a very high probability of being chance.21 The psychologists and educators are far too confident in the significance of results based on a few observations or a short period of time, even though they are trained in statistical techniques and are aware of the dangers. This is a very important cognitive error and is often repeated in markets in a wide range of circumstances.

For example, investors regularly flock to mutual funds that are better performing for a year or few years, even though financial researchers have shown that the “hot” funds in one time period are often the poorest performers in another. The final verdict on the most sizzling funds in the 1996–2000 dot-com bubble shows why this decision making can be disastrous. During the bubble, tens of billions of dollars flowed into the Janus Capital Group. Its short-term record was spectacular. The flagship Janus Fund surged 10.3 percent ahead of the rapidly rising S&P 500 in 1998 and 26.1 percent in 1999, just before the bubble burst. Still, over the ten years ending in 2003, despite its hot hand when dot-com stocks were flying, the Janus Fund averaged only an 8.7 percent return, which meant it underperformed the market by 22 percent over the entire time frame, including both the dot-com bubble and the crash afterward.

Even this grim statistic doesn’t do justice to the damage wrought by Janus. The Janus Fund’s assets were only $9 billion in 1993 but reached $49 billion by March 31, 2000, only weeks after the dot-com market peaked. A large number of its customers arrived too late to enjoy the fabulous returns in the 1990s but were there to get bludgeoned in the ensuing bear market. Needless to say, that crowd received a lot less than the 8.7 percent Janus returned for the decade.

Chasing the hot hand ends in disaster more times than not. Some of Janus’s competitors in the hot-stock derby performed just as badly. Fidelity Select Telecommunications Equipment fund beat the S&P by 12.4 percent in 1998 and 45.5 percent in 1999, while the AllianceBernstein Technology Fund bested the index by 34.6 percent and 50.7 percent, respectively, in those two years. In spite of the huge years in which the dot-com stocks trounced the performance of everything else, the Fidelity fund lagged behind the S&P 500 by 6 percent, and the AllianceBernstein fund was about flat, annually, for the ten-year period ending December 31, 2003. During this bubble, investors lost many hundreds of billions of dollars in red-hot tech and Internet mutual funds as well as in the hot stocks themselves. The so-called hot funds, it turned out, could not hold a candle to the long-term records of many conservative blue-chip funds.22

Another way in which investors regularly make decisions based on much too small a sample of results is putting way too much faith in “hot” analysts. Investors and the media are continually seduced by “hot” performance, even if it lasts for the briefest of periods. Money managers or analysts who have had one or two sensational stock calls, or technicians who call one major market move correctly, are believed to have established a credible record and can readily find a market following for all eternity.

In fact, it doesn’t matter if the adviser was repeatedly wrong beforehand; the name of the game is to get a dramatic prediction out there. A well-timed call can bring huge rewards to a popular newsletter writer. Eugene Lerner, a former finance professor and a market letter writer who headed Disciplined Investment Advisors, speaking of what making a bearish call in a declining market can do, said, “If the market goes down for the next three years you’ll be as rich as Crassus. . . . The next time around, everyone will listen to you.”23 With hundreds and hundreds of advisory letters out there, someone has to be right. Again, it’s just the odds. We do have lottery winners, despite the fact that many millions of tickets may have to be sold to get one.

Elaine Garzarelli gained near-immortality when she purportedly “called” the 1987 crash. Although, as she was the market strategist for Shearson Lehman, her forecast was never published in a research report nor indeed communicated to the company’s clients, she still received widespread recognition and publicity for this call, which was made in a short TV interview on CNBC.

Since this “brilliant call,” her record, according to a fellow strategist, “has been somewhat mixed, like most of us.”24 Still, her remark on CNBC that the Dow could drop sharply from its then-5,300 level rocked an already nervous market on July 23, 1996. What had been a 57-point gain for the Dow turned into a 44-point loss, a good deal of which was attributed to her comments. Only a few days earlier, Ms. Garzarelli had predicted that the Dow would rise to 6,400 from its then value of 5,400. Even so, people widely followed her because of “the great call in 1987.”

Jim Cramer, the popular CNBC commentator—and an ex–hedge fund manager—whom we met earlier, was one of the most voracious cheerleaders of the high-tech dot-com bubble. In a December 27, 1999, missive he wrote, referring to money managers who refused to buy enormously overpriced dot-com stocks, “The losers better change or they will lose again next year”25—this less than three weeks before the dot-com market collapsed.

Shortly thereafter, Don Phillips, then the president and CEO of Morningstar, blasted Cramer for outspokenly playing an active role in reinforcing this enormous bubble, noting in passing that his public recommendations were down 90 percent. Barron’s followed Cramer’s subsequent record and stated that he had underperformed the market for several years after the high-tech bubble. Although Cramer’s record is hardly sizzling, the law of averages dictates that some of his recommendations have to go up. Cramer is astute at blowing these recommendations out of proportion and is probably more popular today than ever.

Make a few good calls, and you’re a hero for a while and the chips pile up in front of you. Being a wannabe gunslinger may not have kept you alive long in the Old West, but it works just fine with investors and the media today. A new Psychological Guideline is helpful here.

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 4: Don’t be influenced by the short-term record or “great” market calls of a money manager, analyst, market timer, or economist, no matter how impressive they are; don’t accept cursory economic or investment news without significant substantiation.

Sometimes the evidence we accept because of the law of small numbers runs to the absurd. Another good example of the major overreaction this heuristic bias causes is the almost blind faith investors place in Federal Reserve or government economic releases on employment, industrial production, the health of the banking system, the consumer price index, inventories, and dozens of similar statistics.

These reports frequently trigger major stock and bond market reactions, particularly if the news is bad. For example, if unemployment rises one-tenth of 1 percent in a month when it was expected to be unchanged or if industrial production falls slightly more than the experts expected, stock prices can fall, at times sharply. Should this happen? No. “Flash” statistics, more times than not, are nearly worthless. They are the archetypal case of mistaken decision making due to the law of small numbers. Initial economic and Fed figures are revised, often significantly, for weeks or months after their release, as new and more current information flows in. Thus an increase in employment, consumer purchasing, or factory orders can turn into a decrease or a large drop in each as the revised figures appear. These revisions occur with such regularity that you would think investors, particularly the pros, would treat the initial numbers with the skepticism they deserve. Yet too many investors treat as Street gospel all authoritative-sounding releases that they think pinpoint the development of important trends.

Just as irrational is the overreaction to every utterance by Fed Chairman Bernanke or his predecessor, Alan Greenspan, ignoring the fact that they entirely missed the subprime mortgage crisis from 2005 through mid-2007. Still, the market hangs on every new comment of Chairman Bernanke and the chairmen of the twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks, from New York and Philadelphia to Dallas and San Francisco, as it does to other senior Fed or government officials, no matter how offhand or contradictory to one another the comments are, or how mediocre the chairmen’s forecasting records have been overall.

Like ancient priests examining chicken entrails to foretell events, many pros scrutinize every remark and act upon it immediately, even though they are often not sure what it is they are acting on. Remember the advice of a world-champion chess player who was asked how to avoid making a bad move. His answer: “Sit on your hands.”

But too many investors don’t sit on their hands; they dance on tiptoe, ready to flit after the least particle of information as if it were a strongly documented trend. The law of averages indicates that dozens of experts will have excellent records—usually playing popular trends—often for months and sometimes for several years, only to stumble disastrously later. These are the lessons that investors have learned the hard way for centuries, and that have to be relearned with each new supposedly unbeatable market opportunity.

One of the results of the tendency to see similarities between situations is to fail to appreciate the lessons of the past. We neglect to study the outcomes of very similar situations in prior years. These are called “prior probabilities” and logically should be looked at to help to guide present decisions, but our ability to disregard them is truly astonishing.26 It is another major reason we so often overemphasize the case rate and pay little attention to the base rate.

The tendency to underestimate or ignore prior probabilities in making a decision is undoubtedly one of the most significant problem of intuitive prediction in fields as diverse as financial analysis, accounting, geography, engineering, and military intelligence.27

Consider the case of an interesting experiment in which a test was conducted with a group of advanced psychology students.28 They were given a brief personality write-up of a graduate student that was intended to give them no truly relevant information with which to answer the question they were then going to be asked about him: what subject he was studying. The assessment was said to have been written by a psychologist who had conducted some tests on the subject several years earlier. The analysis not only was outdated but contained no indication of the subject’s academic preference. (Note that psychology students are specifically taught that profiles of this sort can be enormously in-accurate.)

Here’s what they had to read:

Tom W. is of high intelligence, although lacking in true creativity. He has a need for order and clarity and for neat and tidy systems in which every detail finds its appropriate place. His writing is dull and rather mechanical, occasionally enlivened by somewhat corny puns and flashes of imagination of the sci-fi type. He has a strong drive for competence. He seems to have little feeling and little sympathy for other people, and does not enjoy interacting with others. Self-centered, he nevertheless has a deep moral sense.

Tom W. is currently a graduate student. Please rank the following nine fields of graduate specialization in order of the likelihood that Tom W. is now a student in that field. Let rank one be the most probable choice:

Business Administration

Computer Sciences

Engineering

Humanities and Education

Law

Library Science

Medicine

Physical and Life Sciences

Social Science and Social Work

Given the lack of substantive content, the graduate students should have ignored the analysis entirely and made the only remaining logical choices—by the percentage of graduate students in each field: in other words, the base rate. That information had also been provided to them. It was assumed by the experimenters that the graduate students would realize that those were the real data. They had been taught that for a specific situation, the more unreliable the available sketch, the more one should rely on previously established information—that, to use the language of cognitive psychology, the “case rate” (the profile of subject Tom W.) should not have been conflated with the “base rate” (the known percentage of graduate students enrolled in each field). Did the experiment’s group members realize that the base rate was the only accurate data they had? They did not!

The student subjects relied entirely upon the irrelevant profile, deciding that computer sciences and engineering were the two most likely fields Tom W. would enter, even if those fields had relatively few enrollees.

But we shouldn’t be too hard on those grad students. Investors in the stock market make similar mistakes all the time, as we’ve seen, being repeatedly impressed by the case rate, even though the substantiating data for it are usually flimsy at best. Too many buyers of red-hot technology stocks in the dot-com bubble failed to consider that the average price decline in very similar stocks in each previous technology bubble collapse had been about 80 percent—repeat, 80 percent. That was the base rate they should have been taking into account.

Let’s make this into another Psychological Guideline:

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 5: The greater the complexity and uncertainty in the market, the less emphasis you should place on the case rate, no matter how spectacular near-term returns are, and the more on the base rate.29

The previous cognitive biases, stemming from representativeness, buttress one of the most important and consistent sources of investment error. As intuitive statisticians, we do not comprehend the principle of regression to the mean. This statistical phenomenon was noted more than a hundred years ago by Sir Francis Galton, a pioneer in eugenics, and is important in avoiding this major market error. Studying the height of men, Galton found that the tallest men usually had shorter sons, while the shortest men usually had taller sons. Since many tall men come from families of average height, they are likely to have children shorter than they are; similarly, short men are likely to have children taller than they are. In both cases, the height of the children was less extreme than the height of the fathers. In other words, the heights of the children regressed to the mean height for the population as a whole.

The study of this phenomenon gave rise to the term “regression.” The effects of regression are all around us. In our experience, most outstanding fathers have somewhat disappointing sons or daughters, brilliant wives have duller husbands, people who seem to be ill adjusted often improve, and those considered extraordinarily fortunate eventually have a run of bad luck.30

Take the reaction we have to a baseball player’s batting average. Although a player may be hitting .300 for the season, his batting will be uneven. He will not get three hits in every ten times at bat. Sometimes he will bat .500 or more, well above his average (or mean); other times he will be lucky to hit .125. Within 162 regular Major League scheduled games, whether the batter hits .125 or .500 in any dozen or so games makes little difference to the average. But rather than realizing that the player’s performance over a week or a month can deviate widely from his season’s average, we tend to focus only on the immediate past record. The player is said to be in a “hitting streak” or a “slump.” Fans, sportscasters, and, unfortunately, the players themselves place too much emphasis on brief periods and forget the long-term average, to which the players will be likely to regress.

Regression occurs in many instances where it is not expected and yet is bound to happen. Israeli Air Force flight instructors were chagrined after they praised a student for a successful execution of a complex maneuver, because it was normally followed by a poorer one the next time. Conversely, when they criticized a bad maneuver, a better one usually followed. What they did not understand was that at the level of training of these student pilots, there was no more consistency in their maneuvers than in the daily batting figures of baseball players. Bad exercises would be followed by well-executed ones and good exercises by bad ones. Their flying regressed to the mean. Good landings were followed by poor ones; skillful gunnery was followed by missing the target and good formation flying by ragged patterns. Correlating the maneuver quality to their remarks, the instructors erroneously concluded that criticism was helpful to learning and praise detrimental, a conclusion universally rejected by learning theory researchers.31

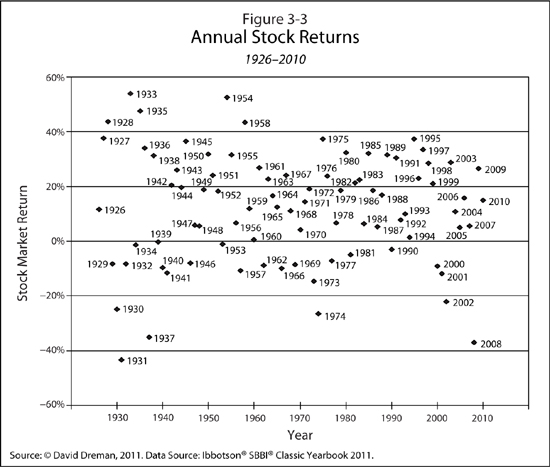

How does this work in the stock market? According to the classic work on stock returns of Roger Ibbotson and Rex Sinquefield, then at the University of Chicago,32 stocks have returned 9.9 percent annually on average (price appreciation and dividends) over the eighty-five years to 2010, against a return of about 5.5 percent for bonds. An earlier study by the Cowles Commission for Research in Economics showed much the same return for stocks going back to the 1880s.

As Figure 3-3 shows, however, the return has been anything but consistent—not unlike the number of hits a .300 career hitter will get in individual games over a few weeks. There have been long periods when stocks have returned more than the 9.9 percent mean. And within each of those periods, there have been times when stocks performed sensationally, rising sometimes 40 percent or more in a year. At other times, they have seemed to free-fall. Stocks, then, although they have a consistent average, also have “streaks” and “slumps.”

For investors, the long-term rate of return of common stocks, like the long-term batting average of a ballplayer, is the important thing to remember. However, as intuitive statisticians, we find this very hard to do. Market history provides a continuous example of our adherence to the belief that deviations from the norm are, in fact, the new norm.

Investors of 1927 and 1928 or 1995–1999 thought that returns of 25 to 35 percent were in order from that time on, although they diverged far from the mean. In 1930, 1931, 1973, 1974, and 2007–2008, they believed that huge losses were inevitable, although they, too, deviated sharply from the long-term mean, as Figure 3-3 clearly shows. Investors of mid-1982, observing the insipid performance of the Dow Jones Industrial Average (which was lower at the time than in 1965), believed stocks were no longer a viable investment instrument; BusinessWeek ran a cover story shortly before the great bull market began in July 1982 entitled “The Death of Equities.”33 By 1987, the Dow had nearly quadrupled. And of course, by the late 1990s Wall Street gurus believed that major bear markets were a thing of the past because the Fed had finally mastered the business cycle. Those optimistic thoughts lasted for a shorter period than the average Reno marriage.

The same scenarios have been enacted at every major market peak and trough. Studies of investment advisers’ buying and selling indicate that most experts are closely tied, if not pilloried, to the current market’s movement. The prevalent belief is always that extreme returns—whether positive or negative—will persist. The far more likely probability is that they are the outliers on a chart plotting returns and that succeeding prices will regress toward the mean, as Figure 3-3 indicates.

We can lose sight of the relevance of long-term returns by detailed study of a specific trend and intense involvement in it.34 Even those who are aware of long-term standards cannot always see them clearly because of preoccupation with short-term conditions. The long-term return of the market might be viewed like the average height of men. Just as it is unlikely that abnormally tall men will beget even taller men, it is unlikely that abnormally high returns will follow already high returns for long, if at all.

But because experts in the stock market are no more aware of the principle of regression than anyone else is, each sharp price deviation from past norms is explained by a new, spurious theory.

Another reason we can so easily lose sight of the longer-term truths we should be factoring into our investing choices is the flood of information we must contend with. TMI, the abbreviation for “too much information,” became common slang in the early 2000s. Though TMI is often used as a jocular interjection, applied to cases when you’ve been forced to know more about some person or something inconsequential than you really care to, there’s a serious side to TMI: the problem of investor information overload. It’s been brought on by the torrent of data available to us today, the processing power of modern computers, and the ubiquitous communication tools we have at our fingertips, and it’s no laughing matter.

TMI is anything but new. I’m reminded of the soothsayers’ dire warnings to Londoners many months before February 1, 1524. Those expert prognosticators warned, on the basis of massive astrological evidence, that on that day the Thames, that most tranquil of rivers, would suddenly rise hundreds of feet, drowning all who remained in the city. That sent a goodly portion of the city population fleeing weeks before the appointed day, although they soon realized that their prescientific experts were a bit off the mark. The Thames, needless to say, flowed peacefully on within its banks.

The returning population was enraged; many wanted to throw the pack of soothsayers into the river in sacks. The soothsayers, aware of what might happen, huddled together and told the enraged populace that the stars were never wrong, indeed that the flood predicted would take place. But they had made the slightest of errors in their very complex calculations. The flood would occur on February 1, 1624, not February 1, 1524. The good people of London could go home—at least for a while.

What exactly happens when we’re confronted with TMI or, to put it in more formal terms, “information overload”?

In 1959, the polymath Herbert Simon, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics, was one of the first academics to rigorously look at information overload. In the simplest formulation, what Simon established was that not only does more information not necessarily bring about better decisions; it can lead to poorer ones. This is because humans cannot process large amounts of information effectively. In Simon’s words, “Every human organism lives in an environment that generates millions of bits of new information each second, but the bottleneck of the perceptual apparatus certainly does not admit more than 1,000 bits per second, and possibly much less. We react consciously to only a minute portion of the information that is thrown at us.”35

And we are biased in the way we do this. Professor Simon notes that this filtering process is not a passive activity “but an active process involving attention to a very small part of the whole and exclusion, from the outset, of almost all that is not within the scope of attention.”36 The key to the bias, he observed, is that when people are bombarded with information they see only the part they are interested in and screen out the rest. More recent research has backed up this finding, including work by Professors Baba Shiv and Alexander Fedorikhin in 1999,37 as well as Professor Nelson Cowan in a research paper in 2000.38

In the context of the stock market (and other trading markets), who suffers most from information overload? It’s hard to give the nod to either the professional or the individual investor. The sheer volume of information is nearly unfathomable. Consider just the large number of securities analysts, sometimes twenty or more covering a single company, who must put out research reports and updates, not to mention all the information they must process on related companies, the industry, the market, and other important economic and financial data. Information overload? More like information breakdown. These are people working every day, faced with hundreds, if not thousands, of analytical factors that conventional investment theory insists must be considered, from competition and profit margins across a wide range of product lines to the likelihood that industry and company earnings will rise or fall because of new developments.

This vast, sometimes staggering amount of market information, much of which is complex and contradictory, is nearly impossible to analyze effectively. As we saw in chapter 2, this is an important reason money managers show such poor results over time and only a very small number of analysts and money managers outperform the market. Of course, under these conditions, you can bet that Affect and heuristics are a predictable fallback. (If you very carefully read between the carefully hedged, well-crafted lines of a lot of investment recommendation reports, you may see Affect or a cognitive heuristic peeking out.) This despite the elaborate decision-making process undertaken by highly educated men and women supported by large corporate resources.

I’m afraid we’re all just going to have to live with market TMI and information overload, but, as we’ll see in Part IV, there are methods that can help us neutralize their negative effects. Let’s now look at a few other ways that our brains go wrong in dealing with other heuristic errors.

There is yet another powerful heuristic bias stemming from representativeness. This is the intuitive belief that psychological inputs and outputs should be closely correlated. Companies with strong sales growth (the inputs) should be accompanied by rising earnings and profit margins over time (the outputs). We believe that consistent inputs supply greater predictability than inconsistent ones do. Tests, for example, show that people are far more confident that a student is likely to have a B average in the future if he has two Bs rather than an A and a C, although the belief is not statistically valid.39 To translate this into stock market terms, investors have more confidence in a company that has 10 percent earnings growth that rises consistently year after year than they do in one that has 15 percent growth over the same period but is more volatile, i.e., 18 percent in year 1, 3 percent in year 2, 15 percent in year 3, and so on.40

Another direct application of this finding is the manner in which investors equate a good stock with a rising price and a poor stock with a falling one. One of the most common questions analysts, money managers, and brokers are asked is “If the stock is so good, why doesn’t it go up?” or “If contrarian strategies are so successful, why aren’t they working now?” The answer, of course, is that the value (the input) is often not recognized in the price (the output) for quite some time. Contrarian stocks have outperformed the market for many decades, but that doesn’t mean they can’t underperform for one year or even a few years—remember the lessons we learned about regression to the mean a couple of sections back. Yet investors too often demand immediate, though incorrect, feedback and can make serious mistakes as a consequence.

Another interesting aspect of this phenomenon is that investors mistakenly tend to place high confidence in extreme inputs or outputs. As we have seen, Internet stocks in the late 1990s were believed to have sensational prospects (the input), confirmed by prices that moved up astronomically (the output). Companies’ strong fundamentals in each bubble went hand in hand with sharply rising prices, such as prices for HMO stocks in the mid-1990s or the computer software and medical technology stocks of 1968 and 1973. Extreme correlations between rapidly growing dot-com companies and hockey stick–like stock charts look great, and people are willing to accept them as reliable auguries, but as generations of investors have learned the hard way, they don’t last.

The same thinking is applied to each crash and panic. Analysts and money managers pull back the earnings estimates and outlooks (the inputs) as prices (the outputs) drop. Graham and Dodd, astute market clinicians that they were, saw the input-output relationship clearly. They wrote that “an inevitable rule of the market is that the prevalent theory of common stock valuations has developed in rather close conjunction with the change in the level of prices.”41

As we’ve seen, demanding immediate success invariably leads to playing the fads or fashions that are currently performing well rather than investing on a solid fundamental basis. An investment course, once plotted, should be given time to work. The immediate investor matching of inputs and outputs serves to repeatedly thwart this goal. The problem is not as simple as it may appear; studies have shown that businessmen and other investors abhor uncertainty.42 To most people in the marketplace, quick psychological input-output matching is an expected condition of successful investing. Taking advantage of this constantly repeated heuristical error by investors is also a critical part of the strategies to be proposed in Part IV. The consistency of this behavior leads us to our next Psychological Guideline.

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 6: Don’t expect that the strategy you adopt will prove a quick success in the market; give it a reasonable time to work out.

Let’s briefly look at two other systematic heuristic biases that tend to cause investment errors. They, too, are difficult to correct, since they reinforce the others. The first, known as “anchoring,”43 is another simplifying heuristic, which sets up a price for a stock that is not far removed from its current trading price as its anchor. In a complex situation, such as the marketplace, we choose some natural starting point where we think the stock is a good buy or a sale and make adjustments from there. The adjustments are typically insufficient. Thus an investor in 1997 who wanted to buy might have thought a price of $91 was too high for Cascade Communications, a leader in PC networking, and $80 was more appropriate. But Cascade Communications was grossly overvalued at $91 and dropped to $22 before recovering modestly. The heuristic process tends to drop the anchors far too close to the stock’s current price, and investors don’t seem to believe prices can go either much lower if they want to sell or much higher if they want to buy; this often leads to missed opportunities.

The final bias is also interesting. In looking back at past mistakes, researchers have found, people believe that each error could have been seen much more clearly if only they hadn’t been wearing dark- or rose-colored glasses. The inevitability of what happened seems obvious in retrospect. Hindsight bias seriously impairs proper assessment of past errors and significantly limits what can be learned from experience.44

Looking back at the 2007–2008 housing crash, many investors blame themselves because it seems the housing bubble was so obvious. We also knew that the number and variations of derivatives were almost mind-boggling. Some of us saw clear instances of major overleverage in subprime lenders such as NovaStar Financial, New Century Financial Corporation, and many others and acted on them early, at the beginning of 2007.

But what most of us didn’t know until after the financial markets began to melt down was the extent of the leverage in the entire financial system, which was multiplied enormously by the increase of specialized obtuse and complex derivatives as well as the intentional enormous replication of poor-quality subprime loans by numbers of banks and investment bankers. Much of this information came out only in late 2009 and 2010, well after the financial debacle, through the actions of House and Senate committees that subpoenaed e-mails and other information from the banks, credit-rating agencies, and investment banks involved. Most investors also did not know how poor the regulation was prior to the bubble that allowed the leverage to get so out of hand, or how enormously overrated subprime mortgages were by Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s, and Fitch.*11 In early 2011, scathing bipartisan reports were released by the two key Senate commissions: the Wall Street and the Financial Crisis Commission, chaired by Carl Levin (chairman of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations); and the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, chaired by Phil Angelides, investigating the debacle. The reports evidence how risky lending, poor bond assessments by regulatory and credit-rating agencies, and major conflicts of interest by some of the Street’s largest firms contributed to one of the worst financial disasters in U.S. history. The commissions wrote scathing reports about the actions of major financial players from Goldman Sachs to Washington Mutual; these reports were turned over to the Department of Justice, which is now investigating the charges, some of which may well be criminal. It all seems so obvious in hindsight, but, as the above examples show, it is nightmarishly difficult to see at the time. As a result, we think mistakes are easy to see and are confident we won’t make them again—until we do. This bias, too, is difficult to handle. Again, that walk to the library may be as good a solution as any, showing us that mistakes that now seem so obvious to us were anything but at the time they were made.

We have repeatedly seen the seductiveness of current market fashions, how prudent investors could be swept away by the lure of huge profits in mania after mania through the centuries. Now, with some knowledge of availability, representativeness, and the other decisional biases we’ve looked at, we can understand why the lure of quick profits has been so persistent and so influential on both the market population and the expert opinion of the day.

Whatever the fashion, the experts could demonstrate that the performance of a given investment was statistically superior to other less favored ones in the immediate past and sometimes stayed that way for fairly long periods (the case rate beats the base rate). Circumstances are really different this time!

The pattern repeats itself continually. A buyer of canal bonds in the 1830s or blue-chip stocks in 1929 could argue that though the instruments were dear, each had been a vastly superior holding in the recent past. Along with the 1929 crash and the Depression came a decade-and-a-half-long passion for government bonds at near-zero interest rates. After a whipping in the markets, investors flock to safety, no matter how little they earn. We repeated the desire for safety by dashing into Treasuries at near-zero interest rates after the crash of 2007–2008 and again in August 2011.

Investing in good-grade common stocks came into vogue in the 1950s and 1960s, and by the end of the latter decade, the superior record of stocks through the postwar era had put investing in bonds into disrepute. Institutional Investor, a magazine exceptionally adept at catching the prevailing trends, presented a dinosaur on the cover of its February 1969 issue with the question “Can the Bond Market Survive?” The article continued, “In the long run, the public market for straight debt might become obsolete.”45

The accumulation of stocks shot up dramatically in the early seventies just as their rates of return were beginning to decrease. Bonds immediately went on to provide better returns than stocks. Professionals tended to play the fashions of the day, whatever they were. One fund manager, at the height of the dot-com bubble, noted the skyrocketing prices of the high-tech and Internet stocks at the time and said that their performance stood out “like a beacon in the night.” We all know too well the rocks that beacon led to.

Although market history provides convincing testimony about the ephemeral nature of very high or low returns, generation after generation of investors has been swept up by the prevalent thinking of its day. Each trend has its supporting statistics. The trends have strong affective and heuristic qualities. They are salient and easy to recall and are, of course, confirmed by rising prices. These biases, all of which interact, make it natural to project the prevailing trend well into the future. The common error each time is that although the trend may have lasted for months, sometimes for years, it is not representative and is often far removed from the performance of equities or bonds over longer periods. In hindsight, we can readily identify the errors and wonder why, if they were so obvious, we did not see them earlier.

The major lesson I hope you take away from this chapter is that the information-processing shortcuts we use all the time, though highly efficient in day-to-day situations, systematically work against us in the marketplace. We just are not good information processors in many ways, and the effects of cognitive biases on our decision making are enormous, not only in investing, but in economics, management, and virtually every area of life.

Even so, these findings have been almost completely disregarded by mainstream economics. The prevailing theory of the markets, the efficient-market hypothesis, rejects virtually all of the psychology we’ve just considered. Instead it posits that investors are rational information processors at almost all times. In order to see just how misleading the tenets of this hypothesis are and how damaging they can be to your investment earnings, let’s now take a close look at the hypothesis and the many reasons it should be discarded—or at the least should not govern your own investment decisions.