7. Pound’s Métro, Williams’s Wheelbarrow

EZRA POUND, “IN A STATION OF THE METRO”

As he recalled it,

I got out of a train at, I think, La Concorde and in the jostle I saw a beautiful face, and then, turning suddenly, another and another, and then a beautiful child’s face, and then another beautiful face. All that day I tried to find words for what this made me feel. That night as I went home along the rue Raynouard I was still trying. I could get nothing but spots of colour. I remember thinking that if I had been a painter I might have started a wholly new school of painting.… Only the other night, wondering how I should tell the adventure, it struck me that in Japan, where a work of art is not estimated by its acreage and where sixteen syllables are counted enough for a poem if you arrange and punctuate them properly, one might make a very little poem which would be translated about as follows:—

“The apparition of these faces in the crowd :

“Petals on a wet, black bough.”1

Early in March 1911, Ezra Pound arrived in Paris. By late May he had moved on. The specters in the Métro obviously haunted him. The lines were finished by fall the following year, when he sent Poetry a batch of poems that, he hoped, would “help to break the surface of convention.”2 When these “Contemporania” were published at the head of the April 1913 issue, the poem appeared in this fashion:

IN A STATION OF THE METRO

The apparition of these faces in the crowd :

Petals on a wet, black bough .3

The first thing striking about the couplet is the subject—beauty discovered underground. (The magazine altered the title’s full caps in Pound’s manuscript, where the small doings underground seem overwhelmed by the massive sign above, to small caps, the magazine’s house style for parts of a sequence. Pound had put “Metro” in quotation marks.) The previous century, Turner in Rain, Steam and Speed—The Great Western Railway (1844) and Monet in his views of Gare Saint-Lazare (1877) had brought the railroad to painting; but it would be hard to call the results traditional. Turner’s oil is a little terrifying—a rabbit flushed from cover dashes ahead of the locomotive—while Monet’s frontal portraits of ironclad leviathans are steamy visions. The works resemble fever dreams, suggesting how difficult it is for the artist to venture outside the approved list of salon subjects. To do so is to court rejection—but not to do so lets art fossilize the taste of the past.

The material culture of poetry often lags a generation behind the world outside. The shock of modernity in Pound’s couplet has faded, but it’s jarring to compare what he was writing before that fateful encounter in the Métro. In Ripostes (1912): “When I behold how black, immortal ink / Drips from my deathless pen—ah, well-away!” and “Golden rose the house, in the portal I saw / thee, a marvel, carven in subtle stuff.”4 A smattering of modern diction seeps in elsewhere, but Pound’s imagination had been steeped in Victorian vagaries, with a weakness for the long-baked poeticisms of “’twould” and “’twas,” of “hath” and “’neath” and “ye” and “thou,” the language of Nineveh reconstructed from torn-up pages of the King James Version. Pound’s English resembles the appalling translations of Gilbert Murray, which should have killed off interest in Greek tragedy forever.

The most dramatic poem in the book is Pound’s faux-barbarian version of “The Seafarer”—rough-hewn, archaisms for once used to effect, the weatherbeaten rhythms of alliterative Anglo-Saxon smuggled into a premodern English that never existed. The poem looks forward to Pound’s experiments with Chinese translation in Cathay (1914), which inaugurated the idiom in which he did his best work—no longer burdened by nineteenth-century haberdashery, he found a verse line adequate to his rough inflections.

It was at the end of Ripostes, in his prefatory note to “The Complete Poetical Works of T. E. Hulme,” that Pound coined the term “Les Imagistes.”5 Innocent readers may have thought Hulme just as much a figment of imagination as Hugh Selwyn Mauberly, Pound’s later alter ego. We probably owe to the Englishman (and not just to his example of plain speech, graven image) Pound’s interest in Japanese and Chinese verse. The spring after the American arrived in London in 1908, he joined the Poets’ Club—Hulme, the secretary, reminded Pound of a Yorkshire farmer. F. S. Flint later remembered that members had written “dozens” of haiku “as an amusement.… In all this Hulme was ringleader.”6

Hulme, who died in the war, helped bring the American’s medievalism up short. (Ford Madox Ford was another bluff influence. On reading Pound’s Canzoni [1911], he rolled about the floor, presumably howling the while at the preposterously stilted English.)7 We should also not underestimate the effect of reviewers, who wrote things like, “If Mr. Pound can find a foreign title to a poem, he will do so. Queer exotic hybridity!”8 Pound was sometimes slow to change—after 1920, there was an increasing refusal to change—but during a crucial decade he could be goaded into brilliance.

Beginning in 1909, Pound became a frequent visitor to the Print Room at the British Museum. There he was probably exposed to the extraordinary collection of ukiyo-e prints gathered by the curator, his friend Laurence Binyon.9 From such accidents and oddments, such stray collisions, Pound manufactured his new style. Only the month before “In a Station of the Metro” appeared, his fellow traveler Flint had contributed the article “Imagisme” to Poetry, a manifesto for the new poetry Pound was promoting:

1. Direct treatment of the “thing,” whether subjective or objective.

2. To use absolutely no word that did not contribute to the presentation.

3. As regarding rhythm: to compose in sequence of the musical phrase, not in sequence of a metronome.10

Pound added dicta of his own, “A Few Don’ts by an Imagiste,” which elaborated the orders of battle, among them:

Use no superfluous word, no adjective, which does not reveal something.

Don’t use such an expression as “dim lands of peace.” It dulls the image. It mixes an abstraction with the concrete. It comes from the writer’s not realizing that the natural object is always the adequate symbol.

Go in fear of abstractions. Don’t retell in mediocre verse what has already been done in good prose. Don’t think any intelligent person is going to be deceived when you try to shirk all the difficulties of the unspeakably difficult art of good prose by chopping your composition into line lengths.

Use either no ornament or good ornament.11

The minor vogue and rapid extinction of Imagism, a movement whose influence we still feel, has been hashed over by literary critics for a century. Its rehearsal here is merely to bring the poem into focus within the slow progress toward the densities of language, the images like copperplate engraving, that made Pound Pound.

When you read Pound’s early poems book by book, his transformation is the more remarkable. In Personae (1926), which collected poems published before The Cantos, he pared his apprentice work of many of its embarrassments, almost a hundred of them. The poems absent are rarely as good as those he chose to keep, though the latter have the young Pound’s same brash overreaching; the varnished diction (“Holy Odd’s bodykins!” “a fool that mocketh his drue’s disdeign”);12 the curious tone with contrary modes of sapheaded ardor and bristling hostility; and the contempt for modern life, cast into antique dialect. (No other modern poet started as a contemporary of Chaucer.) The worst of the discarded are deaf to their own high comedy: “Lord God of heaven that with mercy dight / Th’ alternate prayer wheel of the night and light,” and “Yea sometimes in a bustling man-filled place / Me seemeth some-wise thy hair wandereth / Across my eyes.”13 It took a long while for Pound to practice his preaching—he saw the direction for English poetry before he could follow it. Though he never entirely shook off the archaic trappings and the high romance of the troubadours, Imagism taught him to focus on image and let it whisper meanings he’d been shouting, Sturm und Drang fashion, with a bushel of exclamation marks attached.

The mechanics for change were in place. Then came the occasion, a letter from Harriet Monroe, editor of the newly launched Poetry: “I strongly hope that you may be interested in this project for a magazine of verse and that you may be willing to send us a group of poems.”14 Pound initially gave her a couple of poems lying on his desk, but the opportunity was too tempting to squander. Monroe was a dreadful poet and a conventional editor, but Pound saw the advantage of being the magazine’s house cat—he immediately granted her exclusive rights to his verse and agreed to become Poetry’s foreign correspondent.15 Monroe gave him a toehold among American literary magazines; he in turn provided access to the avant-garde abroad. The literary cities of the day were still Boston and New York. A magazine devoted only to poetry and founded in the uncultured heartlands not far from the Great American Desert was a novelty. (Think of the New Yorker’s scorn for the old lady in Dubuque even a decade later.)16

The best things in Poetry’s first years were the poems by Pound, Eliot, Frost, and Yeats, as well as Pound’s hammer-and-tongs prose—Pound brought the others into the fold. In the fall of 1912, only a couple of months after the letter, he offered Monroe the job lot of “Contemporania.” (That he briefly considered calling the series “March Hare” pleads an intention both whimsical and provocative.)17 In March came the articles on Imagism, the theory. Then at last, the next month, “Contemporania.”

“In a Station of the Metro” is the rare instance of a poem whose drafts, had they survived, might retain the relic traces of a complete change of manner, from gaslit poeticism to the world of electric lighting and underground rail. “Contemporania” showed Pound’s first acquaintance with the modern age, with the deft gliding of registers, the slither between centuries of diction, that made virtue of vice: “Dawn enters with little feet / like a gilded Pavlova,” “Like a skein of loose silk blown against a wall / She walks by the railing of a path in Kensington Gardens,” “Go to the bourgeoise who is dying of her ennuis, / Go to the women in suburbs.”18 (In American poetry, it has never hurt to knock the suburbs.) His embrace of the modern is not a rupture with the past—there is antiquarian fussiness enough—but an acknowledgment that the past underlies the present, that present and past live in sharp and troubled relation. “In a Station of the Metro” is the final poem of the group.

At the beginning of his most productive years (roughly 1912 to 1930), Pound might as well have been a medieval troubadour yanked into the modern world. When he describes the woman in Kensington Gardens, he remarks, “Round about there is a rabble / Of the filthy, sturdy, unkillable infants of the very poor”19—it’s not clear whether this judgment betrays her prejudice or his Swiftian realism (or not so real, since infants of the poor died in droves). Already a certain chagrin clung to the earlier poems. Addressing them, he admits, “I was twenty years behind the times / so you found an audience ready.”20

Pound’s biographer Humphrey Carpenter called “Contemporania” a “blast to announce the appearance of a new circus-act,” the poems “written in a hurry and to fill a gap.” Pound referred to their “ultra-modern, ultra-effete tenuity”—and these “modern” poems, as he called them elsewhere, were quickly parodied by Richard Aldington, among others.21 Pound must have thought better of them, because he included a few in his Catholic Anthology (1915) and all but one in Lustra (1916).22 It would hardly have been the first time a writer, lashing out against his contemporaries, found the way forward. Pound’s genius, when he was young, was as restless as Picasso’s. Ambition is gasoline.

“IN A STATION OF THE METRO”

A title is not usually the first line of a poem. It may exist in tenuous or digressive proximity to what follows, at times merely the equivalent of an easel card propped to one side of the stage or the placard flourished by a bikini-clad model between rounds of a prize fight. The title may tell us merely where we are, or how far along. Here it flows seamlessly into the first line; but its status, like so many features of the poem, remains ambiguous. “In a Station of the Metro” was, as a title, a challenge to an aesthetic that would not have seen as poetry a poem set in such unromantic surrounds. The history of poetry has repeatedly been the march of the unpoetic into the poetic.

After the title, the first presence is almost an absence—apparitions are neither here nor there but halfway between two worlds, between seen and unseen, appearance and disappearance. The link to the supernatural is as old as the word—“apparition” first described a ghost, employing a term used in Latin of servants, whose presence could be summoned. The degrees of meaning spread from the reappearance of a star after occultation to the appearance of the infant Christ to the Magi, also called the Epiphany. These faces call up the shades of the Odyssey, where the dead Elpenor is referred to by the Greek word “eidolon,” a specter or phantasm. The dead there lived in darkness; if you attempted to hold them they faded from your hands, insubstantial, “like a shadow / or a dream.”23

Pound’s recollection of the Métro would have been more or less vivid when recorded for T.P.’s Weekly in June 1913. Setting down that moment a year later for the Fortnightly Review, he added new details:

I wrote a thirty-line poem, and destroyed it because it was what we call work “of second intensity.” Six months later I made a poem half that length ; a year later I made the following hokku-like sentence :—

“The apparition of these faces in the crowd :

Petals, on a wet, black bough.”24

(The indentation seems to have been the magazine’s choice, not Pound’s.) Pound was enough of a classicist, and a showman, to know the advantage of arriving in medias res—indeed, there is scarcely another way to start when the end is almost the beginning. Those passengers drifting by are not revenants, but they rise from the gloom of the underground station. The old-fashioned spaces before semicolons and colons affect the text of the poem. (Such spaces have been removed from Pound’s prose below.) Note the introduction after “petals” of a comma soon to vanish again.

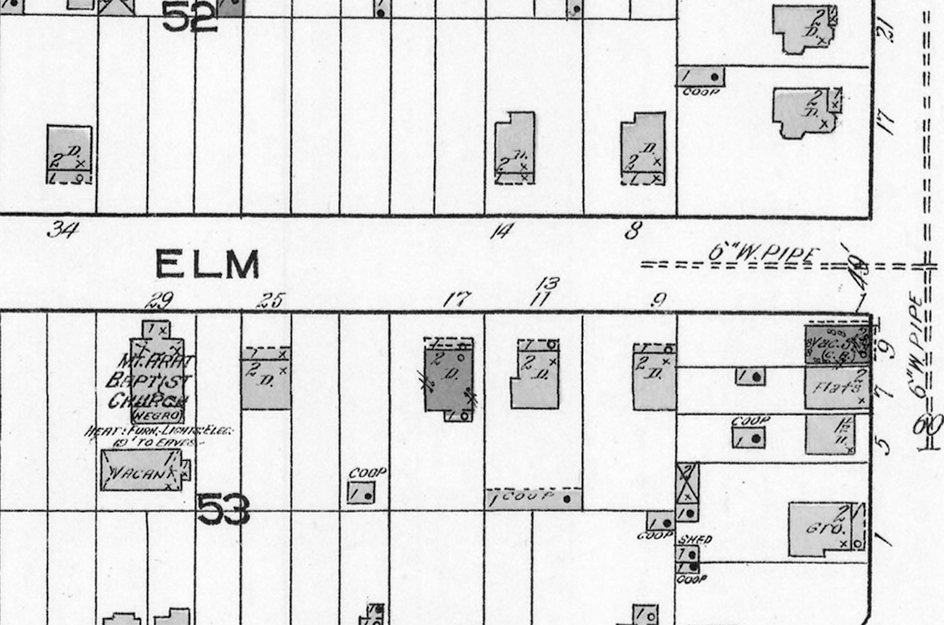

The Métro had opened scarcely a decade before, during the Paris World Fair—or Exposition Universelle—in the summer of 1900.25 The trains ran on electric motors, and the electric lighting on the platforms provided artificial daylight. London’s underground stations had been choked by the steam and sulfurous coal-smoke of engines that scattered cinders on the waiting crowds. One traveler remarked on the “smell of smoke, the oily, humid atmosphere of coal gas, the single jet of fog-dimmed light in the roof of the railway carriage, which causes the half-illumined passengers to look like wax figures in a ‘Chamber of Horrors.’ ” Wax figures! An American, aghast at the “sulphurous smoke” that left the London stations “filled with noxious fumes,” reported that “leading medical experts” believed the Underground responsible for a “large number of new diseases,” “ailments of the heart or lungs,” “headache and nausea.”26 Those wax figures give us an idea of what Pound saw.

Paris was lighter and cleaner. Still, standard bulbs were weaker then, and houses brightly lit compared to the days of candlelight and gas jets would seem a miasma now. An early photograph of the Gare de Lyon station shows a shadowy realm barely interrupted by the faint glow of ceiling fixtures (the scene is probably lighter than normal because of the photographer’s flash).27 There is a witness. In September 1911, a few months after Pound’s visitation, another traveler came to Paris and recorded in his diary that “in spite of the electric lights you can definitely see the changing light of day in the stations; you notice it immediately after you’ve walked down, the afternoon light particularly, just before it gets dark.”28 This was Franz Kafka. Had the day been rainy, the station would have been even darker.

A crowd is the city’s signature, especially for those from the country. Recall Wordsworth in London, a century before:

How oft, amid those overflowing streets,

Have I gone forward with the crowd, and said

Unto myself, “The face of every one

That passes by me is a mystery!”29

This is nearly the experience of “In a Station of the Metro”—but recall, too, Eliot’s Dantesque London a few years after: “A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many, / I had not thought death had undone so many.”30 Pound’s vision occurred in a “jostle,” he says; but the poem is all stillness, a freeze frame as static as haiku.

Paris Métro, Gare de Lyon, 1900.

Source: Collection of Julian Pepinster—DR.

The interiors of most early stations, including La Concorde, were lined with chamfered white tiles, highly glazed—these dispersed the light and in later photographs give the interior a watery look.31 Pound’s poem depends on the daylight above the darkness below, not least because a visit to the underworld is a visit to the dead. Readers would have known the journey of Odysseus in Odyssey 11 (the Nekuia), or of Aeneas in Aeneid 6. The ritual slaughter of sheep, whose blood drew the dead to Odysseus, must already have been ancient when Homer composed his verses.

The comparison to petals is stark; but the gists and hints go deeper, as well as the sense of loss. The classic haiku demands a reference to season taken from a time-honored list—perhaps Pound knew that much. (How well he knew Japanese verse is moot, since he apparently believed haiku required, remember, sixteen syllables and punctuation.) However the scene occurred in the lost longer drafts of the poem, through the juxtaposition of painterly images he may have come to this brief form—it might very simply be translated into Chinese. Pound’s construction of the series was fluid and contingent, but on one point he told Monroe he was adamant: “There’s got to be a certain amount of pictures to ballance [sic] the orations, and there’s got to be enough actual print to establish the tonality.”32

Paris Métro, reflective lighting.

Source: Collection of Julian Pepinster—DR.

The intention of the image is plain—beyond the strewn blossom lies transience. In his reminiscence in the Fortnightly Review, Pound says he “saw suddenly a beautiful face, and then another and another, and then a beautiful child’s face, and then another beautiful woman.”33 The beauty of petals—roughly oval, like faces—lasts but a week; the faces in the Métro are like those of the dead, the lives however long too short in retrospect. Indeed, the dead never age. In the underworld, young women remain beautiful; children, children.

Despite the faint tincture of the classics, Pound’s petals seem immediately present. In the Paris spring, these might have been the palest pink of cherry blossoms or the rouge-tinted white of plum. Cherry trees may have been blooming in the Jardin des Tuileries above the station. “A wet, black bough”: bough here, therefore probably a tree, though “boughs of roses” is not unknown. In a minor poem from Exultations (1909), “Laudantes Decem Pulchritudinis Johannae Templi,” Pound praised the “perfect faces which I see at times / When my eyes are closed— / Faces fragile, pale, yet flushed a little, like petals of roses.”34 The image was in the warehouse.

Pound would have left the Métro in sight of the giant red-granite obelisk erected in the long octagonal square by King Louis-Philippe in 1829, less than forty years after it had served as the site of the guillotine. There Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, Robespierre, and Danton met their fates. Known as la place de la Révolution during the Terror, the square was afterward renamed, not without the luxury of irony.

Blossoms wither and fade, lives wither and fade. Those visions in the Métro, so casually encountered, might have been at the peak of a beauty that death, like art, would arrest, had arrested. The poem depends on the electric shock of seeing the bloom of such faces in the murk underground. That’s the point. Beauty rises here from the sordid darkness, a motif familiar from Aristotle’s notion that life emerged spontaneously from rotting flesh. Had the lighting been better, the faces would not have been so striking. These are faces in the crowd, so he is probably ignoring some in favor of others—his eye was drawn to beauty.

The poem works that ground between nature and civilization, country and city, pastoral and metropolitan. (We should be disconcerted by the pastoral image materializing in the unfeeling world of the machine.) The dunghill versus harmony. The Georgics versus the Aeneid. Pound built the image out of the clash of prejudices. Paris of course had its own underground city of the dead—the Catacombs, whose entrance lay on what had been known as Hell Street (rue d’Enfer). The poet stayed at a pension no great distance away when he arrived in Paris in 1911.35

Pound noted in “A Few Don’ts” that “An ‘Image’ is that which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time.… It is the presentation of such a ‘complex’ instantaneously which gives that sense of sudden liberation; that sense of freedom from time limits and space limits; that sense of sudden growth, which we experience in the presence of the greatest works of art.”36 Pound was unusual in being able to examine, almost with calipers, what he was doing—and what he intended to do. The poem here is theory writ small, or theory is the poem writ large. The poem is an interleaving of juxtapositions—not just the image of the faces versus that of the petals, but the acuteness of a title so casually and harshly modern versus the ghostly faces and blown petals after. The simplicity of the poem lives above a confusion of staccato confrontations.

The conjunction of images binds the worlds together as much as it holds them apart. This is Pound’s phanopoeia at its most basic. The beauty exists in eternal confrontation with the squalid, but it is beautiful in part because of that squalor. After Pound, there was not a poet who could requisition the power of such images until Geoffrey Hill. Pound’s crucial critical idea of the period, applied directly to translation, was the distinction between melopoeia, “words … charged, over and above their plain meaning, with some musical property”; phanopoeia, a “casting of images upon the visual imagination”; and logopoeia, the “ ‘dance of the intellect among words.’ ”37 This first appeared in “How to Read, or Why” (1929), but he was using the terms melopoeia and logopoeia at least as early as 1921.38

The image, however exact physically, trembles with ambiguity. Do the faces look wet in the liquid light of the Métro? Was it raining above, the passengers having rushed into the darkened station from a shower? (That Pound mentions only women and a child among the faces suggests that this might be late afternoon, the women having spent the day in the gardens above, perhaps driven into the subway by the rains.) Are the petals from blossoms torn apart by spring rain, stuck to the wet bough, to fall when the sun returns? Or are they blossoms freshly opened in clusters along a branch? Pound’s familiarity with ukiyo-e prints might indicate sprays of cherry or plum blossom (Hokusai and Hiroshige contributed important examples),39 but seeing one face after another suggests solitary petals. Pound likely had a single thought in mind, not two—such minor puzzles the reader must hold at bay. Some of the disconcerting play rooted in the poem lies between the static and dynamic terms of the image: petals pasted in stillness or clusters buffeted by a breeze. If the exact date mattered, as it does not, amid the usual showers of early spring in 1911, Paris had two prolonged periods of heavy rain, March 12–18 and April 27–29.40 (The end of the Paris cherry or plum blossoms is usually mid-April.) The dates are merely idle speculation; but idle speculation is not the worst way to attack a poem, so long as it’s no more than that.

What of the black bough? Perhaps the gloom suggested it. (The thicker the crowd, the fainter the light.) The atmosphere, dark enough already, would have been filled with the smoke of men indulging in pipes or cigarettes.41 Yet the original Métro cars were made of dark varnished wood. Though some still ran on other lines, those no longer passed through La Concorde. The new metal-clad cars, however, had been painted brown (later deep green) in imitation of the wooden models; it’s not clear if Pound could have seen the difference in the Stygian darkness of the station.42 (Kafka: “The dark colour of the steel sides of the carriages predominated.”)43 That might have been enough, had Pound seen the faces against the dark backdrop of the wooden cars, or what he recollected as wood.

Aeneas’s descent into the Underworld through the wide-mouthed cavern of Avernus in Aeneid 6 might also lie behind the image of Pound’s half-lit station.44 The Art Deco entrances built for the Métro, of which many remain, feature two tall curving posts like spindly flower stalks, each topped by a small red lamp. Mark Ovenden remarks in Paris Underground that these lamps “were said to look like the Devil’s eyes at night; the steps of Hades down his throat leading to the belly of the beast!”45 Unfortunately, Ovenden cannot recall the source; and Julian Pepinster, perhaps the most knowledgeable historian of the Métro, does not think the comparison ever made. It is suggestive but, alas, likely unhistorical.

One entrance at La Concorde did not possess these spiry posts—it also served as an exit. It was scarcely less gloomy, however. In a photograph of 1914, this entrance appears as a shadowy arched mouth cut into a stone facade along the border of the Tuileries, the sign METROPOLITAIN capped by five small bulbs, probably red, to cast light upon it through the dark. This wide-mouthed stone entrance is the only one that might have provoked classical thoughts in Pound. There, if we take him at his word, he would probably have emerged from the underworld.46

The poet, given his turn of mind, might have recalled another passage in the Aeneid—where Aeneas rode Charon’s ferry across the Styx. The trains come and go, as endlessly as the ferry of the dead. Perhaps Pound recalled the sulfurous atmosphere of the London Underground, not completely electrified even then. Until bridges and subways were built, the ferry remained the common carriage across water in all river cities—London, Paris, New York. If we take the journey of the dead further, the pale-faced figures would be the newly dead rushing to board—Pound saw them pressing toward him, as Aeneas saw the crowds on the bank of the Styx. Other myths muscle in, especially the eternal return of Persephone (invoked in Pound’s Canto 1, a reworking of the Nekuia episode). Surely, had the Métro traveler a tutelary goddess, it would be she.

Paris Métro, La Concorde, 1914.

Source: Collection of Julian Pepinster—DR.

Pound’s tone is nondescript, almost clerical, a notation of image complex in demand and reservation. There’s something of the awe beauty disposes, or abandons in its wake—his transfixion has been transferred to the petals. They have a hypnotic bloom. The anonymous flaneur explains nothing (he gives no motive for his appearance, because the moment does not require motive)—if you didn’t sense the ghostly quality of these presences (ghostly, not ghastly), his remark would not be far removed from forensic. He’s merely the medium of impression, the words that give voice to image. One of the poem’s quiet gestures is that it lets the title establish the surrounds. Pound’s longer recollection registered the stir and arrest of this accidental scene: “In a poem of this sort one is trying to record the precise instant when a thing outward and objective transforms itself, or darts into a thing inward and subjective.”47 Eliot’s idea of the objective correlative, which bears a filial relation, was not mentioned until his essay “Hamlet and His Problems” in 1919.48

The neutrality of voice perhaps owes something to Pound’s stray reading of Oriental translation, though his deeper interest in Chinese poetry came only in the fall of 1913, when the widow of the scholar Ernest Fenollosa gave his papers to the eager young poet. Still, Pound had arrived in Europe toward the end of half a century of Japonisme ushered in by Commodore Perry’s expedition of 1853–1854. That the poet spent time looking at ukiyo-e prints was no odder than his taste for painters like Whistler, that chronic bohemian, on whom the Japanese influence was marked. One of Pound’s friends thought the poet’s outlandish dress and irritating manner mimicked the painter as well.49 “You also, our first great, / Had tried all ways,” Pound wrote of Whistler in 1912, nailing his flag to that mast.50

Translation accounted for the simplicity and directness of Imagism. The poet had in effect thought in an alien language, a tongue he did not know, and translated back to English.

RHYTHM

In the Fortnightly Review memoir, after remarks similar to those on “spots of colour,” Pound added: “It was just that—a ‘pattern,’ or hardly a pattern, if by ‘pattern’ you mean something with a ‘repeat’ in it. But it was a word, the beginning, for me, of a language in colour.”51 He was not referring to rhythm here, but his thoughts on rhythm align in rudimentary form with this moment. (Melopoeia, as he says in ABC of Reading [1934], is where “language charged with meaning” succeeds in “inducing emotional correlations by the sound and rhythm of the speech.”)52 He continues, in the expanded reminiscence, “I do not mean that I was unfamiliar with the kindergarten stories about colours being like tones in music. I think that sort of thing is nonsense. If you try to make notes permanently correspond with particular colours, it is like tying narrow meanings to symbols.”53 There he rejects the relevance of Baudelairean synaesthesia.

Pound certainly had rhythm in mind when he typed out the poem for Harriet Monroe.

The apparition of these faces in the crowd :

Petals on a wet, black bough .54

These spaces might be called phrasal pauses, except the last, which provides emphasis or suspense after “black.” Monroe must have questioned Pound about rhythm, because he replied with a salvo: “I’m deluded enough to think there is a rhythmic system in the d[amned] stuff, and I believe I was careful to type it as I wanted it written, i.e., as to line ends and breaking and capitals.”55 Recall the odd comma after “petals” in the version Pound published in Fortnightly Review in 1914. The phrasal pauses are gone, but he couldn’t quite let go—that comma is the last remnant of a missing space.

The spaces before colon and period might be thought similar to pauses in reading at the end of a line or a sentence (you cannot hear punctuation, not accurately, with perhaps one exception, the question mark). These spaces, however, had no significance—they are simply an artifact. Pound was following an old typographer’s-convention throughout the manuscripts and typescripts of “Contemporania.”56 Perhaps Monroe was so cowed by Pound’s reply she didn’t realize that the terminal spaces of “In a Station” were unnecessary. The other poems lost such spaces in print, but this was the only poem in the group with phrasal pausing in addition. (“Line ends and breaking” referred to enjambment, not spaces before punctuation—but obviously he confused her.) The convention had not entirely vanished in print—you see spaces before all major stops except comma and period in the first edition of Gaudier-Brzeska (1916), as in the Fortnightly Review article that preceded it.

Such rhythms would have been more difficult to enforce before the invention of the typewriter—the typewriter was Pound’s piano. He liked to think of himself as a composer, though his work in that line was not a success—he had a tin ear and a tin voice. His longest composition, the one-act opera Le Testament, is an agony of droning and caterwauling. Pound added, in his salvo, “In the ‘Metro’ hokku, I was careful, I think, to indicate spaces between the rhythmic units, and I want them observed.”57 (“Hokku” was the common name until the end of the previous century.)

Pound’s colored “pattern” has only a sidelong reference to music. Still, there he came as close as anyone to a definition of free verse: free-verse rhythm, too, is not a “pattern,” not something with a “repeat.” (A pattern without a repeat, Pound might have said, meant that poetry should not look like wallpaper.) We are returned to Flint’s notes on Imagism: “As regarding rhythm: to compose in sequence of the musical phrase, not in sequence of a metronome.” Pound’s disruptive idea of rhythm almost demanded that he break the phrasing after “black”—he could not require this without spacing, but when he printed the poem in Catholic Anthology (1915) he gave up trying to bully the reader. The spaces vanished.58 That he had such a rhythm in mind tells us about the poem; that he was willing to abandon the notation tells us about Pound.

The analysis of rhythm does not often consider the length of words or the shift in parts of speech. To chart these things and superimpose them must be clumsy, but if we include the title the map might run:

x x N-N x x N-N

x N-N-N-N x x N-N x x N

N-N x x A A N

where x = articles, prepositions, pronouns, demonstrative adjectives; A = adjectives; and N = nouns. (Polysyllables are hyphenated, metrical stress underlined.) What can we learn from the lines’ DNA? That most nouns appear in the strong positions at the beginning and end of lines, their force amplified by the string of monosyllables at line end, like a series of drum beats. The monosyllabic nouns are more dramatic, and more dramatically placed, than those longer. The rhythm of meter is augmented by the rhythm of syllables. (The meter of the final line mirrors but truncates the meter of the title.)

In Lustra (1916), the poet replaced colon with semicolon.59 (That even here a space precedes the punctuation at the end of the first line of “In a Station” should not be taken as a sign that Pound cared. The space was not lost in Personae (1926) until the revised edition of 1990, long after the poet’s death.)60 The colon surrenders the pale faces to the petals; the semicolon juxtaposes them in equal and trembling rapport. The colon is a compass direction; the semicolon a long rest, a musical notation. (Call it the difference between an equation and an encounter—or a traffic accident.) Pound considered the images superimposed (“The ‘one image poem’ is a form of super-position, that is to say[,] it is one idea set on top of another. I found it useful in getting out of the impasse in which I had been left by my metro emotion.”)61 Call it a jump cut at its sharpest, at its gentlest a dissolve, that technique so beloved of early cinema—Pound’s era. He was thinking of film in that later reminiscence: “The logical end of impressionist art is the cinematograph”—that is, the motion-picture camera. “The cinematograph does away with the need of a lot of impressionist art.”62

As Pound says about the moment of discovery, in the Fortnightly Review memoir, “I do not mean that I found words, but there came an equation … not in speech, but in little splotches of colour.”63 He must have felt in the early version of the poem that he had to direct the reader’s eye from one thing to the other. Later, he was satisfied to nestle the images side by side. The lack of a verb leaves the tenor and ratio of comparison to the reader, as in haiku. The virtue of the sentence fragment is the unease produced when the verb is denied—however this seems to those fluent in Japanese, in English the verb is the absent guest longing to appear. Elijah.

To think of the petals as notes lined up along the musical staff of a bough takes the metaphor beyond its bounds; but, had the words scattered along the line struck Pound as a series of notes, the spaced phrases completed the rhythm of notation. The spacing perhaps prevents the reader from recognizing both lines as iambic, an alexandrine followed by acephalic tetrameter. The tension between iambic rhythm and the rhythm of phrasing gives the poem its motive tension. (The device was frequently used by Frost.) The iambics continue; the phrasings interrupt and stutter. When the poem appeared last in the series of “Contemporania,” the pauses at line end must have seemed more emphatic, lingering, final.

The stamp or impression of “In a Station” would not remain so vivid without indirection. The best of Pound’s early work lies, not in medieval ventriloquism or harangue, but in his new taste for implication. The best example of the method comes from Cathay in “The Jewel Stairs’ Grievance,” his translation of a poem by Li Po (now usually Li Bai):

The jewelled steps are already quite white with dew,

It is so late that the dew soaks my gauze stockings,

And I let down the crystal curtain

And watch the moon through the clear autumn.64

Working from Ernest Fenollosa’s notes, Pound called the poet Rihaku, as he was known in Japan. (Fenollosa had studied the Chinese poems with Japanese teachers.)65 The poem seems slight; but, as he did for no other poem in the short pamphlet, Pound added an instruction manual.

Note.—Jewel stairs, therefore a palace. Grievance, therefore there is something to complain of. Gauze stockings, therefore a court lady, not a servant who complains. Clear autumn, therefore he has no excuse on account of weather. Also she has come early, for the dew has not merely whitened the stairs, but has soaked her stockings. The poem is especially prized because she utters no direct reproach.66

The cunning is worthy of Sherlock Holmes. (Even Pound felt so—when he analyzed the poem in his essay “Chinese Poetry,” he remarked, “You can play Conan Doyle if you like.”)67 The original poem is not in code; but it depends on knowledge of Chinese poetry, including, as Wai-lim Yip notes, the genre of court poetry it imitated. (If Pound did not recognize the genre, Yip argues, he made inspired guesses.68 Holmes, again.) The inductive method, placing the necessities of interpretation entirely upon the reader, had been crucial to “In a Station of the Metro.” This is undoubtedly part of what Pound meant by logopoeia—the “ ‘dance of the intellect among words.’ ”69

The claims of implication, of mysteries deciphered, were developed in even scrappier fashion in “Papyrus,” Pound’s interpretation of a bit of parchment containing fragmentary remains of a poem by Sappho. Pound used only the beginning three lines:

Spring. . . . . . .

Too long. . . . . .

Gongula. . . . . .70

Gongula (more accurately, Gongyla) is a woman’s name.71 The Romantic idea of the fragment, the partial whole (recall “Kubla Khan”), found purchase here, though Pound’s translation of the first two fragmentary lines has been sharply disputed.72 The question is not, is this a love poem, but does a love poem require more?

There remains the mystery of what provoked Pound, bedeviled by the scene in the Métro, to the comparison. In “Piccadilly” (1909), he’d written of “beautiful, tragical faces,” “wistful, fragile faces,” and “delicate, wistful faces”—he was drawn to beauty like a pre-Raphaelite dauber.73 (In “How I Began,” Pound complains, “I waited three years to find the words for ‘Piccadilly,’ … and they tell me now it is ‘sentiment.’ ”)74 More than a little of the pre-Raphaelite survives in Lustra. Consider, among many examples, “discovering in the eyes of the very beautiful / Normande cocotte / The eyes of the very learned British Museum assistant” (“Pagani’s, November 8”)—another louche charmer, another chance encounter.75 After complaints by the printer and publisher, this and other poems thought scandalous had been dropped from the original British edition.76

Was there any shade who might have tormented him during the long revision of the poem? Perhaps. On an earlier visit to Paris in 1910, he had met Margaret Cravens, an American bohemian who became his patron.77 She killed herself with a revolver in June 1912. Her death long troubled her friends, and some mistakenly believed that she had been in love with Pound.78 He wrote an elegy for her, later titled “Post Mortem Conspectu,” intended for the group of “Contemporania,” though he withdrew it and published it elsewhere.79

The incident in the Métro occurred over a year before Cravens’s suicide, but we know from his accounts that Pound revised a long while before his revelation that the inciting moment in all its affliction could be compressed to two images. (The “hokku-like sentence” occurred to him as early as the spring before her suicide.)80 This Parisian ghost might have stalked Pound while he was whittling away the original version. Like Ajax turning from Odysseus in the Underworld, nursing his old grievance, the figures in the Métro do not say a word: “ ‘So I spoke. He gave no answer, but went off after / the other souls of the perished dead men, into the darkness.’ ”81 Kafka remarked, “Métro system does away with speech; you don’t have to speak either when you pay or when you get in and out.”82

Years later, Cravens’s death is recalled in Canto 77 (“O Margaret of the seven griefs / who hast entered the lotus”), where Pound invoked the land of the dead, later mentioning the lotus again, the flower associated with her in his elegy. Then: “we who have passed over Lethe.”83 (His father showed Aeneas the river Lethe, where the dead promised a second body drank to forget.) There was much to forget. It might be tempting to recall the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice—another journey to the underworld to rescue someone dear, and a failure. That presses the possibilities too far. The archeology of image is difficult; and the critic can do little more than strew a few suggestions relevant to the poet’s state of mind, insofar as such a transient thing can be explored at all. The poem does not need Cravens to conjure up the passage through the underworld. If the ghostly faces are the faces of the dead, they steal a little beauty from the petals. If they are the faces of the living, they borrow transience. As apparitions they could be both living and dead.

There may have been a more lingering cause for Pound to be thinking of the dead. One evening in 1903, a fire caused by a train’s short-circuited motor filled the tunnels and Couronnes station with smoke. The lights were extinguished; passengers wandered in darkness, dying along the platform and at a neighboring station. Eighty-four were killed. Pound had visited Paris in 1906, when memory of the fire would still have been fresh. Perhaps he had heard of it. The pale faces crowded along the platform might be an eerie reminder of those who had died underground.84

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.85

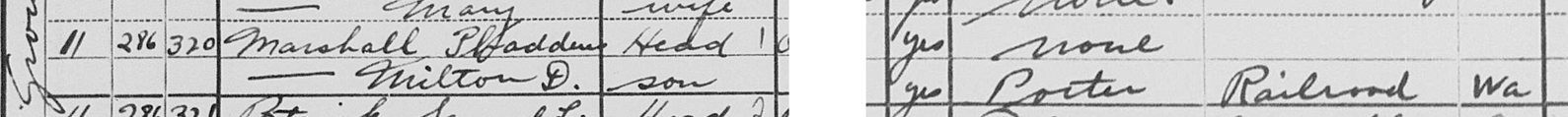

WILLIAM CARLOS WILLIAMS, “THE RED WHEELBARROW”

As he recalled it,

The wheelbarrow in question stood outside the window of an old negro’s house on a back street in the suburb where I live. It was pouring rain and there were white chickens walking about in it. The sight impressed me somehow as about the most important, the most integral that it had ever been my pleasure to gaze upon. And the meter though no more than a fragment succeeds in portraying this pleasure flawlessly, even [as] it succeeds in denoting a certain unquenchable exaltation—in fact I find the poem quite perfect.86

So, William Carlos Williams, having been asked which of his short poems he would like posterity to know, if it could know only one.87 He chose “The Red Wheelbarrow”:

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens88

Published first in Spring and All (1923), this may be among the earliest paeans to modern poetry’s aesthetic particular, the everyday object dragged into the marble galleries of art. The poem’s Shaker English has proved its most unexpected—and telling—contribution to American verse. Anyone might have written in that humbling severity, the poetic equivalent of Grant Wood’s American Gothic. Readers have long been moved by poems anyone might have written—however terrible, however good, such shreds of homespun are often the most deeply loved. You could say “The Red Wheelbarrow” is a Georgic lost in New Jersey.

The scene has been rendered in the plainest Wordsworthian style, the free verse not free but nearly lifeless, a flat, abrupt string of words shaped to its lack of ornament. The eye takes in the scene, but scene must seduce the eye—that is the dual condition of the visual: the charmer charmed, the sorcerer ensorcelled (call it vision if you require the taint of religion). Binocular vision is moral; but perspective is invented in surfaces, whether retina, canvas, or paper.

Rarely has a poem of banalities attracted such sustained close reading. The opening is based on a rhetorical trick, a question left hanging. “So much” of what? The phrase is old, or old enough. So much depends “upon the character of the clergymen” (1832), or “upon servants making fires” (1797), or “upon the man behind the cow” (1916). “Marriage is the most sacred, since so much depends upon it” (1720). So much depends “upon the individual temper of the particular judge” (1902), or “on the nature of the soil” (1828), or “upon the purity of the gold” (1823), or “upon the House of Commons” (1826). “So much depends upon the teacher, and so little upon the text” (1884). “So much depends upon the testimony furnished by the physician” (1825). So much, indeed, “depends upon the eyes of the reader” (1815).89

“So much depends upon circumstances” (1833) is the general way of putting it, yet the philosophical general is as devoid of circumstance as the circumstance of “The Red Wheelbarrow” is devoid of anything else.90 So much depends on this, or that, or something more, but the stakes are absent—we are presumed to know already, yet we know that we don’t know, or know only that “so much” too vague to know. So much of our lives? So much of the world? Williams’s gesture has fueled much later poetry, often suffering lapses into sentimental vagary. There’s nothing more dangerous in rhetoric than the unsaid.

“So much depends …” The thought is fragmentary but not a fragment. The OED says of “much” as a noun, “The word never completely assumes the character of a noun” and “can be modified by adverbs like very, rather.” The phrase “so much” has adjectival and noun uses dating to the early thirteenth century, and as a noun phrase meaning a “certain unspecified amount” it is almost as old, reaching back at least to the late fourteenth century. Its early appearance in the Wycliffite Bible reads, “Womman, seye to me, if ye solden the feeld for so moche?” “So” is one of those words that does duty in the dirty corners of English where formal grammar doesn’t quite hold. It’s doing so still, modifying willy-nilly in fresh turns of phrase: “Fuchsia was so last year,” “You’re so out of here.”

The poem would have been very different phrased as a question and more intelligible had Williams written “so little”—given the trivial details, the shudder of meaning comes only because it is “so much.” (Charting the entanglement of “so much” and “so little” would require phase switching or a two-state quantum system, depending on the measure of irony.) Williams records the force of intention: “The sight impressed me somehow as about the most important … it had ever been my pleasure to gaze upon.” Where the poet proposes and the reader disposes, intention does not limit the poem’s latent meanings. Indeed, by not answering the implicit question, Williams has given the reader free rein; but a reader is usually less interested in the variety of possible response than in what the poet had in mind. Interpreting a poem is like deciphering a message incomplete, with a key partly corrupt.

Critical tactics often reveal the critic more than the poet—and a poem so spare invites overattention. Many critics, like Hugh Kenner, have felt obliged to quarrel with the etymology of “depends”:

“Depends upon,” come to think of it, is a rather queer phrase. Instead of tracing, as usage normally does, the contour of a forgotten Latin root, “depends upon” ignores the etymology of “depend” (de + pendere = to hang from).91

Or Charles Altieri:

How resonant the word “depends” becomes, when we recall its etymological meanings of “hanging from” or “hanging over.” The mind acts, not by insisting on its own separateness, but by fully being “there”: by dwelling on, depending on, the objects that depend on it.92

Such arabesques ignore the appearance of the modern meaning as early as the sixteenth century, not long after the word made its way into English. Williams was unlikely to be thinking of any flutter of ambiguity in the Latin. (A brief scan of the entry for dependeo in Lewis and Short would have shown that the ancients were already familiar with the modern usage. The literal meanings were “to hang from or on” and “to hang down,” not “to hang over.”) You might as well try to squeeze out meaning by saying that “upon,” as the OED reminds us, once implied “elevation as well as contact” or that “rain” seems to have no history before cognates appear in Germanic languages—and therefore might have been of interest to Tacitus, that close student of empire.93 If there were a drop rather than a leaning, it would be found only in the physical relation of three prepositional phrases, “upon” descending from “so much depends,” each seeming to cling vertically to the one before. In the blood relations of grammar, however, “with rain water” modifies “glazed,” while “glazed” and “beside the white chickens” separately modify “barrow.” A sentence diagram would display the relations clearly.

Readers new to “The Red Wheelbarrow,” if not hostile, sometimes become a little giddy on learning that such simple lines can be called a poem. Part of the pleasure derives from its violation of the “poetic,” part from how much the opening promises and how little the poem delivers. (The reader’s longing for meaning is used as an Archimedean lever.) So much depends because of the assertion, but assertion is not argument—“so much depends” is a riddle without revelation, leaving a void where the conclusion should be. The wheelbarrow, the glazing rain, and the chickens may do nothing for the reader; Williams claims no more than that they are obscurely momentous to him. A revelation is a privacy whose interior we are never likely to visit. The poet can render only the aftermath—the rest may remain a mystery even to him. Other readers, other epiphanies: a dog lying on a burnt carpet, an old book left open with a single word circled, red snow drifting across an empty lot. The poem is a Rorschach blot.

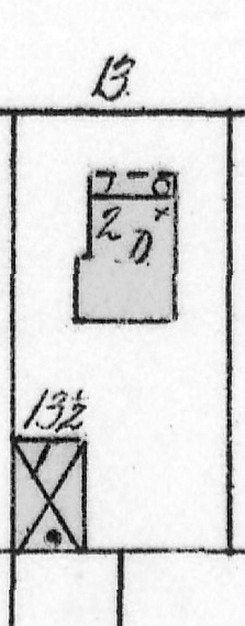

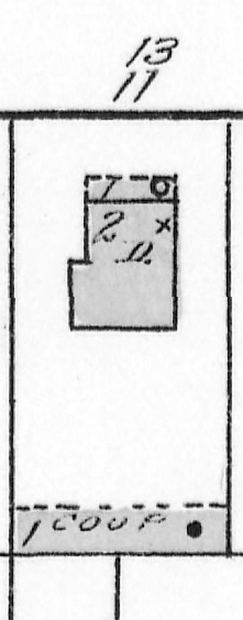

The history of painted wheelbarrows is long and cryptic. Had the color been unusual, Williams might have been startled only by the oddness of the scene. Barrows in the twenties were often still made of wood, which unpainted or unvarnished would soon rot if not kept under cover. Painted wheelbarrows must have been common. A novel from 1841, Rollo at Work, mentions a blue wheelbarrow, as does Leslie’s Monthly Magazine in 1905; the now nearly forgotten Thomas Bailey Aldrich wrote in 1889 in Scribner’s Magazine that “few men who were boys in Portsmouth at the period … but will remember Wibird Penhallow and his blue wheelbarrow.”94 Green wheelbarrows appear in the magazine The Garden of 1904 as well as in The Flag of Truce, a novel of 1878; and a yellow one in Arthur’s Illustrated Home Magazine of 1875, while a 1907 issue of Geyer’s Stationer (“A Weekly Devoted to the Interests of the Stationery and Kindred Trades”) reports that a certain hardware-store owner “paints his store front yellow, he paints his wagons yellow, he paints his pushcarts yellow, and uses a yellow wheelbarrow. He uses yellow stationery and yellow envelopes.”95 As for red wheelbarrows, they can be found in the National Magazine of 1908, the New-Church Messenger of 1918, and the Saturday Evening Post of 1920.96 In this period, the English advice columnist Charlotte Eliza Humphry remarked that a woman at Ascot had worn “almost enough rouge on her face to paint a little wheelbarrow.”97 That would be a red wheelbarrow.

The 1897 Sears catalogue advertised four types of wheelbarrows, including what was called a tubular-steel miners’ barrow, which with its steel “tray” comes closest to what we call a wheelbarrow now.98 The miners’ barrow cost nearly three times as much as the Handsome Lawn Wheelbarrow, which had high, flat wooden sides—the better to carry grass clippings, garden waste, or chicken manure—as well as steel-spoked wheels and “two coats of brightest and best vermillion [sic] paint.”99 This is probably the sort of barrow Williams saw. The slightly more expensive Clipper Garden Wheelbarrow (“nicely painted and striped”) seems too fancy for a working garden, and the two inexpensive railroad-wheelbarrows tipped to the side (made for handling dirt and used in the construction of railroads and canals). The catalogue for 1912 offered six wheelbarrows, four of hardwood and two with steel trays.100 The cheapest garden-barrow, apart from one for boys, was made of hardwood and also painted red. Montgomery Ward’s catalogue of 1922–1923 had similar wooden garden-barrows; though “well painted,” the color goes unremarked.101 The metal wheelbarrows may have been left unpainted.

Vermilion was a brilliant scarlet red containing mercuric sulfide, obtained from ground cinnabar. Used for rouge by the whores of Shakespeare’s day and on our continent in the Indian’s war paint, it was the painter’s preferred red into the twentieth century. By the twenties, however, bright commercial reds were usually made of iron oxides (one writer in 1913 estimated that half the paint coming from paint factories was red). American vermilion, also called chrome red, was a scarlet red chromate, the favorite of barrel makers, wagon makers, and the makers of cabooses.102 There’s a good chance the red wheelbarrow was painted that red.

Sears, Roebuck and Co.’s Handsome Lawn Wheelbarrow, 1897.

Between wheelbarrow and chickens, in these pendant particulars, comes the medium, the glazing rainwater. The glazing is no more than distantly related to the varnish the painter applies, as a last touch, to the canvas. (Williams usually lacked such subtle calculation, to his benefit.) Still, the scene was observed through a frame, a window frame; and the restless movement of the eye from one particular to another mimics—perhaps even enacts—the eye’s passage from object to object in landscape painting. Landscape invites the eye to travel the path of the painter’s reckoning, but the poet in his more limited realm is more ruthless. He judges precisely how the scene will be ordered and read. The poem is an act of managed perception, the visual mechanics conditioned by formal pattern, the parts partial until the whole is grasped. Indeed, “The Red Wheelbarrow” focuses on fragments of a larger scene. It’s perhaps not irrelevant that the eye may be drawn to a dash of red in pastoral, as Constable knew—and hunters of antelope. The still life is not quite, as it were, a nature morte. It’s the nature morte within an invisible nature vivante.

In 1888, five breeds of white chicken—Dirigios, White Javas, White Minorcas, White Plymouth Rocks, and White Wyandottes—were recommended for recognition by the Committee on New Breeds of the American Poultry Association. Three were admitted: the Minorcas, the Plymouth Rocks, and the Wyandottes.103 (One early breeder of White Plymouth Rocks claimed to have been inspired by his boyhood encounter with the white Roc in the Arabian Nights.)104 Other white breeds had long been familiar—the first volume of the association’s American Standard of Excellence in 1874 mentions at least half a dozen.105 The admission of so many new white varieties at once, however, touched off a fad for white chickens.106 These breeds—or one later recognized, like the Rhode Island White, admitted in 1922 to The American Standard (by then renamed The American Standard of Perfection)107—are the likeliest candidates for the fowl stepping blithely through the rain around that wheelbarrow. None of the white breeds dominated, but the White Plymouth Rock was among the most popular. No doubt the owner of those backyard chickens was looking for good layers.108 Chickens of the day were smaller than factory-farmed chickens now.

Everything in the poem exists within the gravity of that wheelbarrow, in the little world introduced by “so much depends / upon …” The mystery of the scene lies in the poet’s casual intensity—he saw the objects as never before. (The early saints experienced such moments of radical vision.) That the extraordinary may be found in the ordinary, the magnificent within the everyday, is a commonplace of scientific discovery, from the barnacles and finches contemplated by Darwin to the melted chocolate-bar that led to the microwave. Late in life Newton is said to have said, “I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea-shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, while the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.”109

It was crucial, however, that the poem remain an exotic—that it never be repeated. Just as Marcel Duchamp in 1917 faced the law of diminishing returns when he followed his porcelain urinal, the first “ready-made” he attempted to exhibit, with a coat rack, Williams would have destroyed the epiphany had he later written that so much depended on a blue barber’s-chair or an alligator suitcase.110 When Heraclitus declared that you can’t step into the same river twice, he went beyond a lesson about getting your feet wet. The first example of the new is revolutionary, the next is shtick.

THE STRUCTURE OF WHEELBARROWS

The poem must find a form equal to its revelation. We know “The Red Wheelbarrow” not just through the words but through the visual arrangement—what lies beyond syntax in the shape of the poem itself. The four unrhymed couplets, varying in their variations, have been stealthily organized, three words laid like a lintel upon one. Syllabic forms, to which this form bears filial affinity, don’t always call so much attention to themselves—when they do (as in Marianne Moore’s poems, to which we’re indebted for the modern syllabic), indentation usually stamps the visual pattern across stanzas. Though it never became part of Williams’s armory, the form of “The Red Wheelbarrow” was almost certainly inspired by the principle of word count in classical Chinese poetry.111 The three-word verses of the Three-Character Classic, which Williams had read a few years before in Chinese Made Easy, had perhaps lodged in his head.112

As a thought experiment, the poem might be rearranged into four-word lines:

so much depends upon

a red wheel barrow

glazed with rain water

beside the white chickens.

The losses of emphasis cannot be offset. The same words are not at all the same poem. In poetry, form matters, as does the sequence of information. The distinctiveness of the original might suggest—even if we knew nothing of Williams’s tastes—the geometric torsion of the Cubists, word count and enjambment making the syntax accountable to angles and surfaces. How unlikely the poem would have been had so much depended upon “the white chickens / beside // a red wheel / barrow // glazed with rain / water.” That might have been titled “The White Chickens” before being instantly forgotten. Had so much depended, however, upon “a red / Duesenberg // glazed with rain / water // beside the snow / weasels,” the poet could have been an even greater hero of the avant-garde.

The visual strategy of the original depends upon violent enjambment to frustrate the stale, flat, unprofitable prose. “Upon // a red wheel / ” could have continued, “chair // glazed with rain / water”—just as “beside the white / ” might have completed the idea with “Russian” or “collar” or “egret.” (Enjambment always invites a mob of ghosts.) The first and last couplets sever a humdrum phrase, the colloquial “depends / upon” and the matter-of-fact “white / chickens.” In the case of such familiar words, momentary shock is more refreshing than examination afterward. The reader’s eye registers the breach—but isn’t more humor packed into such deceits when the stakes are so small?

Rainwater and wheelbarrow: the middle couplets violate compounds that first appeared in English not as pairs but as single words, “rainwater” during the Old English period and “wheelbarrow” in the fourteenth century. The butchery makes the familiar strange again. Words severed by the eye are joined again in speech, as the magician rejoins the lady sawn in half—the shattered portrait is itself a form of revelation. It’s hard not to see here the fracturing influence, the aggressive art of perception, of Juan Gris’s collage Roses or Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, Cubist art Williams knew well. (Duchamp met Williams in the fall of 1915 and visited him at Rutherford the following spring.)113 The eye must consider the elements independently, just as mounting an old shop-sign on a gallery wall or a urinal on a pedestal asks that the object be seen afresh, torn from its usual surroundings.

Williams was working in a tradition, whether he knew it or not. Jonson had enjambed “twi- / Lights,” Milton after him “Mile- / end Greene,” and Hopkins, more ludicrously, “ling- / ering” and “as- /tray,” all for the sake of rhyme. The breach of manners works better as comedy, as in Lewis Carroll’s “two p / ennyworth only of beautiful Soup.” Such nods and winks turn up decades after Williams in Bishop’s “Glens Fall // s” and Lowell’s “duck / -’s web- / foot,” again for rhyme.114 Elsewhere in Spring and All, Williams enjambs the line “That sweet stuff / ’s a lot of cheese.”115 The delay is a rimshot. The execution in “The Red Wheelbarrow” is calculated (no hyphen eases the pain), but so is the understanding that the drama is empty: Williams chose not the Miltonic tease (“yet from those flames / No light”)116 but an anti-Miltonic pratfall, which reveals with a flourish of classical gesture the vacancy of Romantic pastoral. “The Red Wheelbarrow” is an antipoem in more ways than one.

Too much can be made of such things. In the centuries after their appearance, “wheelbarrow” and “rainwater” often as not appeared divided or hyphenated, those engagements through which word pairs usually pass on their way to marriage—the premature wedding was long disputed. They’re still found divided or hyphenated, and even Williams was inconsistent: “our drinking water was rain water,” he wrote in Autobiography (1951). “Rainwater” in the story “A Descendant of Kings” was reprinted two decades later in Make Light of It (1950) as “rain water.”117 The poet had suffered a heart attack and a stroke by then, so perhaps he didn’t notice or care.

In many of Williams’s less successful poems, a scene is exposed and developed like a snapshot (the metaphor comes from hunting). The wheelbarrow and chickens, however, have been set at the distance of art while seeming to possess no art at all. The preamble is also an editorial (or, if you will, a framing device): “so much depends” gestures vaguely then lands with a thud upon “upon.” The couplets that follow perfected modernist enjambment, in which a quiet, unassuming phrase is broken dramatically at line end—only for the next line not to be dramatic at all. It’s like barreling along a highway and seeing, too late to avoid the abyss, a “Bridge Out” sign—except there is no abyss, just a terrifying drop of six inches. The short lines afterward place an object in isolation—barrow, water, chickens—even as syntax knits them together. We might expect a final line-break as cold-blooded as those in the inner stanzas, but Williams has wrong-footed the reader again. Readers enjoy being wrong-footed.

The poem was left untitled until anthologized in William Rose Benét’s Fifty Poets. (Williams perhaps missed the tremor of meaning when he wrote “unquenchable exaltation”—as if the rain had poured down hosannas.) A year later, in 1934, the poet confirmed the title in Collected Poems, 1921–1931.118 As a title, “The Red Wheelbarrow” is shrewd in its effects. First, it pushes the later break of “wheel / barrow” into the deliberately theatrical, though earlier readers, used to seeing the word in various forms, might have thought the amputation not all that daring. Second, the definite article promotes the indefinite wheelbarrow to feature attraction—what had been generic gets top billing. A title often thrusts to the fore the dominant subject or symbol, focusing the eye before the eye sees—the title anticipates the effect it in part creates. Last, the emphasis of “the” suggests that “so much” means a “very great deal” rather than “not all that much” (i.e., “so much and no more”). Either that is not just any wheelbarrow, or any wheelbarrow might have such an effect—but that particular one did for Williams.

The minute adjustments and implications of poetic form seem to reveal the world’s organizing pattern, or merely the pattern the poem takes within the chaos of the ordinary. Consider the unbalanced couplets of “The Red Wheelbarrow,” the first line always three or four syllables (in order, 4–3–3–4), the second a word of two syllables. All but the first disyllable are nouns (the unbalanced arrangement is unlikely a metaphysical point that existence teeters atop essence). One of the things the eye is most alert to is symmetry; and here the poet has produced, not just symmetries in words where there are none in the scene, but local asymmetries within larger symmetries. Syllabic patterns are interesting as far as they go, but they explain few of the poem’s effects. At best, counting syllables reveals some tarry residue of the poet’s workshop; but a poem read aloud almost never gains from a count almost impossible to hear. The sculptural structure, however, forces the inchoate into visual form.

Many critics have labored to detect patterns in sound, which might seem to betray a method of composition bordering on the aesthetic. In practice the repetition of e’s or d’s or w’s matters little. At worst the reader is subjected to tone-deaf analysis, as in the delightful mishmash of Barry Ahearn’s William Carlos Williams and Alterity:

The first and second stanzas are linked by the long “o” in “so” and “barrow” and by the short “uh” in “much,” “upon” and “a.” “L” and “r” interlace the core stanzas (the second and third); these two sounds, however, are not in the first and fourth stanzas.… The central stanzas are mellifluous, the frame stanzas choppy. Then again, however, the honeyed and the choppy are linked in the third and fourth stanzas. They are joined by means of a parallel construction; the long vowels in “glazed with rain” match those in “beside the white.”119

Any aspect of a poem can be made to bear meaning, but not all bear meaning particularly well. In most poems written by a poet with an ear, the sound has been braided; yet the noise the poem makes, melodic or not, rarely calls for meticulous planning. It would be tempting to invoke the Duchess’s advice to Alice, “Take care of the sense, and the sounds will take care of themselves”—but things are rarely that simple.120 Williams once admitted that his “Lovely Ad” was an “inconsequential poem—written in 2 minutes—as was (for instance) The Red Wheel Barrow [sic] and most other very short poems.”121 (The statement was taken from a transcript of his remarks, so the variant title has no significance.)

Much criticism of “The Red Wheelbarrow” consists of observations true but not interesting, observations far less crucial than those interesting but not true. Critics have a talent for overreading matters usually ignored—indeed, things the poet may have done whimsically, carelessly, or without knowledge of the consequences. The early reviewer in Poetry who thought the poem “no more than a pretty and harmless statement”122 is preferable to the later critic who argued himself from design to cornball insight:

The wheelbarrow is one of the simplest machines, combining in its form the wheel and the inclined plane, two of the five simple machines known to Archimedes. Just as civilization depends on number, civilization depends on simple machines.… “So much depends upon” the wheelbarrow in its service not only through the centuries, but as a form whose components are indispensable to the functioning of a highly industrialized civilization.123

“Yeah, yeah,” as the philosopher said. That doesn’t mean minor or accidental choices don’t condition meaning.

The form drives the perceptions of “The Red Wheelbarrow” toward a pacing and pointing they would not have as a line of prose:

So much depends upon a red wheel barrow glazed with rain water beside the white chickens.124

The metrical shape of the poem wrestles against syntax. William has cast the sentence into accentual couplets, with two beats in the first line, one in the second. The technical analysis of meter, unhappily, too often leads to hair-raising sentences of the sort in Kenneth Lincoln’s Sing with the Heart of a Bear:

This third line is composed of two spondees enjambed toward an inverted foot, a trochaic “barrow,” which serves as the wheeling reverse pivot, indeed, of the second line.125

It’s easy to go too far with meter and lose sight of the forest, the trees, and anything sitting on the branches. (Finding two spondees in the third line is impossible.) There is nonetheless something to be said for meter here. If the poem had been cast not in four couplets but two lines, the meter might have been more uniform:

— ' — ' — '

so much depends upon

— — ' — — ' — — ' — — ' — — ' —

a red wheel barrow glazed with rain water beside the white chickens.

The iambic regularity of the opening assertion would be followed by five anapests and a feminine ending, a rhythm disrupted in the original by enjambment and stanza break—as well as by the tendency of some readers to pronounce the word, once broken, as “wheel BARrow,” instead of “WHEEL barrow.” (Williams’s own matter-of-fact reading, in the two recordings I’ve heard, was WHEEL / barrow.” He also said “rain / WATer,” rather than the usual “RAIN / water.”)126 The rhythmic alternation of lines long and short creates minor dramas within the beautiful stutter of enjambment. This is not to suggest that meter so occult fails to give musical underpinning to the whole.

In Fifty Poets, Williams described the meter as “no more than a fragment.” Perhaps he thought the poem too brief to establish meter—more likely, in his inexact way, he simply meant the rhythm had been cut short. The reader may discover various emotional cognitions and recognitions in rhythm, recognitions that might be no more than chance—yet how carefully Williams has deployed and interrupted meter here, keeping the regularity dormant. His calculation is no less cunning than that of Ezra Pound when he introduced the long spaces into early printings of “In a Station of the Metro.” Free verse is often a way of troubling the reader’s hearing, of refusing uniformity in favor of unpredictable rhythmic variety—jazz, in other words.

SPRING AND ALL

“The Red Wheelbarrow,” so famous in isolation, was not intended for isolation. It first appeared in the long sequence Spring and All (1923), where Williams tried to give his work aesthetic ground by interspersing untitled poems with off-the-cuff critical musing. Williams felt indignant, as he remembers in Autobiography, that Pound and Eliot had crippled American poetry:

Out of the blue The Dial brought out The Waste Land and all our hilarity ended. It wiped out our world as if an atom bomb had been dropped upon it and our brave sallies into the unknown were turned to dust.… I felt at once that it had set me back twenty years.… Critically Eliot returned us to the classroom just at the moment when I felt that we were on the point of an escape.127

Williams was a raggedy thinker, and through Spring and All the aesthetics have been scattered according to some shotgun technique. After a preamble, the reader is confronted by Chapter 19, then Chapter XIII (its title printed upside down), Chapter VI, Chapter 2, Chapter XIX, sections III, Chapter I, then sections III–XXVII, with section VII missing or unnumbered. (“Chapter headings are printed upside down on purpose,” he recalled in I Wanted to Write a Poem [1958], “the chapters are numbered all out of order, sometimes with a Roman numeral, sometimes with an Arabic, anything that came in handy.”)128 The book is a fossil of the avant-garde sensibility of the flapper era. Shock repeated wears into tedium, yet this hurrah’s nest, stuffed with rubbish like “Wrigley’s, appendecitis [sic], John Marin: / skyscraper soup— // Either that or a bullet!,”129 contains three of Williams’s most extraordinary early lyrics: “By the road to the contagious hospital,” “The pure products of America go crazy,” and “so much depends.”130

Biographia Literaria might have been such an omnium gatherum of critical whimsies had Coleridge possessed no plan and suffered a course of opium emetics. Williams gives a Cook’s tour through the muddle of his imagination, often not bothering to finish his sentences (“It is the imagination that—”).131 “The prose is a mixture of philosophy and nonsense,” he later admitted.132 The remarks trailing “The Red Wheelbarrow,” which must be considered linked to it, try to parse the difference between prose and poetry:

Poetry has to do with the crystallization of the imagination—the perfection of new forms as additions to nature—Prose may follow to enlighten but poetry—

“There is no confusion,” he ends these thoughts, “only difficulties.”133 What such reflections omit is the extraordinary way Williams sculpts the threadbare sentence into a sharp-witted poem. Compare the bathos of the previous poem in the sequence, also in couplets:

one day in Paradise

a Gipsy

smiled

to see the blandness

of the leaves—

so many

so lascivious

and still.134

It took another decade, until “This Is Just to Say” ended “so sweet / and so cold,” for Williams to give warmth to such blowsy rhetoric.135 On the rare occasions when he came close to reproducing the form of “The Red Wheelbarrow,” in poems like “To a Mexican Pig-Bank,” “Between Walls,” and two or three others, the writing collapsed into slack lines and high-school banality.136

Does Spring and All mean “Spring and the Universal All,” “Spring and Everything That Follows,” “Spring Miscellany,” or, say, “Spring and All That Nonsense”? Only the last would pay real homage to the American demotic. (“I write in the American idiom,” Williams once remarked—or boasted.)137 The title goes at least this far: spring is present in fructifying possibility, with hints of resurrection and the defeat of death. “The Red Wheelbarrow” would be very different had the sequence been titled Winter and All. The scene would have become an abandoned barrow, chill rains, chickens soon to meet their fate, a world of dreariness and decay. Symbols are weathervanes—they point where the wind blows. Laid back into the sequence in which it appeared, the poem looks more didactic, achieving its depths through surface comprehensions.

THE RIFLING OF SOURCES

Williams’s imagination was so permeable to the influences of the period, it’s impossible to trace the exact sources that formed the peculiar provenance and complex of properties, the sealing of affectations, that formed “The Red Wheelbarrow.” A poem is often the sole record of the particular incident or private meditation that moved the poet to speech; the relation between figure and ground is necessarily complex. Teasing out the strands of invention that have implication for the words on the page cannot provide the critic with an easy answer, only a more difficult set of questions.

As with all discussions of influence, the critic investigates long after the crime has been committed; without the poet’s sworn testimony (leaving, like all testimony, ample room for forgetfulness, wishful thinking, and the plain fib), these can be only hints and misses. A poet can bear witness to his intentions, so far as he recalls them, but not to those meanings that struggle or bully in unawares. The roll call of influence here is long, or longish, but the core would include:

The Ezra Pound of “In a Station of the Metro” and Cathay (1915) (all the matter and canter of Imagism)—Pound’s attempt to purge poetry of Georgian lacemaking and gingerbread, focusing the line through the indelible image in the belief that, if exact enough, if hemmed in with enough implication, plainspoken American would possess the brute vigor of Elizabethan English.

Classical Chinese and Japanese poetry, largely through translations by Arthur Waley and Pound, as well as the latter’s imitations.138 The influence is already apparent in some short poems in Williams’s Sour Grapes (1921): “The Soughing Wind,” “Spring,” “Lines,” “Memory of April,” “Epitaph.”139

The avant-garde artists of the day (particularly Duchamp and Williams’s favorite painter, Juan Gris).140 Most influential were their attempts to make everyday objects into art, and their desire to distort or disrupt the tired mechanics of seeing. Not to be ignored are phenomenology, already influential before World War I, and the photographic movement toward seeing the immediate without ignoring that it is being seen, from which came Alfred Stieglitz.

The longing for a true American poetry, which can be traced back to Emerson’s essay “The Poet” (“We have yet had no genius in America, with tyrannous eye, which knew the value of our incomparable materials.… Our logrolling, our stumps and their politics, our fisheries, our Negroes, and Indians, our boa[s]ts, and our repudiations … are yet unsung”).141 Eliot and Pound were apostates here. Williams was willing to use Pound’s methods against him.