8. Dickinson’s Nerves, Frost’s Woods

EMILY DICKINSON, “AFTER GREAT PAIN, A FORMAL FEELING COMES”

After great pain, a formal feeling comes—

The Nerves sit ceremonious, like Tombs—

The stiff Heart questions ‘was it He, that bore,’

And ‘Yesterday, or Centuries before’?

The Feet, mechanical, go round—

A Wooden way

Of Ground, or Air, or Ought—

Regardless grown,

A Quartz contentment, like a stone—

This is the Hour of Lead—

Remembered, if outlived,

As Freezing persons, recollect the Snow—

First—Chill—then Stupor—then the letting go—1

STANZA 1

“Not born” yourself, “to die,” you must reverse us all.

—to Samuel Bowles, about 1875

Not surprisingly for a poet in love with reversals, Dickinson began with syntax head over heels. To launch so rhetorically confesses that the lines were scribbled after deliberation—and calculation. Since the Romantics, many poems sound as if the poet had written in the heat of passion—emotion not recollected in tranquility, as Wordsworth had it, but before the tears had stopped. That is a lie agreed upon.

English often gains traction by inverting normal word order. Other languages have different rules of engagement—the German verb, that bane of simultaneous translators, often straggles along at the tail of the sentence; and it’s not out of order for the Aeneid to begin, “Arma virumque cano.” Inversion in English is the rhetorical signal that rhetoric is present, so a certain formality noses in even before “formal” has been whispered. Inversion of syntax does not reveal, as some critics have it, an inversion of theme, feeling, or argument. That’s not the way writers usually think.

The task of the poet is, not to succumb to rhetoric, but to take advantage of it. Even a good poet might not have been aware of an opportunity beforehand—or troubled to analyze the profit, knowing subconsciously the choice was right. Milton recognized the power of delay when he began Paradise Lost, “Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit,” an extended prepositional phrase that prevented him from getting round to subject and verb until the sixth line. (Call it acting out the speech act, or purpose by design—drama delayed is the promise of style.) Dickinson began over one hundred and fifty poems with prepositions, as many as begin with “I.”

Her inversion resolves a problem in syntax: “A formal feeling comes after great pain” would have destroyed the pentameter line, as well as any resistant energy the line might have had. When poets compose in brief forms, rhythm is ever-present (Dickinson’s iambics vary here from trimeter to pentameter). Had the phrase “a formal feeling comes” occurred to her first, she’d have realized without thinking that “after great pain” could not follow. The inversion makes peace with the meter and restores chronology—it’s appropriate that the poem start with pain.

Though minute investigation of the dramaturgy of meter is better kept to a minimum, it would be hard not to notice the pitch forward of the inverted first foot, the monumental stolidity of the spondee “great pain” that follows, and the tripping light-footedness of “a formal feeling comes.” Whatever music meter grants is underscored here by alliteration, the more emphatic the shorter and closer the words. The device’s musical qualities depend on other factors and may require more distance. A sensitive ear should detect the falling quality of fore-stressed words like “formal” and “feeling,” casting the line downward in contrast to the rising iambics, as if formal feeling were decrescendo after pain. To work line by line toward the choreography of emphasis and velocity would stress too minutely what is better experienced, like a fireside tale—or a joke. The affect of meter always triumphs over intention. Still, there are moments when analysis proves by no means negligible.

Taxed with grave thoughts, Dickinson might have recalled the passage from the opening of The Winter’s Tale, another fiction touched by cold: “the reverence / Of the grave wearers. O, the sacrifice! / How ceremonious, solemn, and unearthly.”2 “Ceremonious” is sometimes used disparagingly for outward form rather than inward feeling. The rituals of etiquette after a death inform grief while assuaging it; indeed, ritual is the formal repetition that consecrates marriage, baptism, rites de passage, coronation, and the sanctification of the dead. Here, though, emotion seems unassuaged, though the stages of freezing to death are also treated as invariant rite—chill, stupor, submission. The speaker doesn’t know if the Hour of Lead can be outlived, and in the ritual of poetic form creates a symbolic death.

This social, stoical metaphor counterfeits the century’s obsequies of mourning. When the grieving gathered at the house of the dead, the corpse was laid out in the parlor, while mourners kept nightlong vigil nearby. The custom was recorded in Huckleberry Finn (1884):

I peeped through a crack of the dining-room door, and see the men that was watching the corpse all sound asleep on their chairs. The door was open into the parlor, where the corpse was laying, and there was a candle in both rooms.3

And in this New York recollection of about 1830: “The hall and rooms being filled, I stood upon the piazza, which opened by a large raised window into the parlor where the corpse lay in a coffin, clad in grave-clothes.”4 (The older tradition of mourners surrounding the deathbed was fading out by the mid–nineteenth century.)

The dead whom Dickinson had known were buried or entombed. Banned by the Catholic Church until 1963, banned still by the Eastern Orthodox Church, cremation was long considered pagan and sacrilegious. A grave is a metaphorical tomb—aboveground tombs were usually reserved for the rich, who could afford to build them. Though Dickinson’s tombs are abstractions, the world of her nouns is largely abstract, like that of Shakespeare’s sonnets. Still, she knew more of tombs than the tombs in books. In a letter of 1855, while visiting her father in Washington, her farthest trip from home, she wrote to friends, “Hand in hand we stole along up a tangled pathway till we reached the tomb of General George Washington.”5 The overgrown path may have led to the Old Tomb, a simple crypt faced with plain brick. The bodies of the general and his wife had been moved two decades before, however, to the much grander New Tomb, for which he had left a bequest. This mausoleum stands across from a pair of stone obelisks, as if he were a pharaoh.

Dickinson would probably have seen the Amherst town tomb in West Cemetery. Built a few years before the poem was written, it stored bodies democratically through a hard New England winter, when frozen ground could not be broken. The low, gloomy granite-fronted vault, covered in sod, lay not far from her house, the only tomb in the graveyard where the poet, her sister, and her parents were later buried. (Her white coffin was carried, at her request, out the back door of her home and across the fields.)6 Dickinson’s poems live in abstraction, but abstractions may be fleshed.

The trappings of the poem recur in lines probably written a year later,

No Bald Death—affront their Parlors—

No Bold Sickness come

To deface their stately Treasures—

Anguish—and the Tomb.7

The “Sweet—safe—Houses— / Glad—gay—Houses—” that open the poem are caskets—caskets “Sealed so stately tight— / Lids of Steel—on Lids of Marble,” hiding lavish interiors, “Brooks of Plush—in Banks of Satin.” The parlors are the parlors of the dead, where death can no longer visit. (For such houses of the dead, recall “Safe in their alabaster chambers,” with its “Rafter of satin, and roof of stone.”)8

In the opening stanzas of “After great pain,” the speaker’s body is dissected and personified, as if Heart and Nerves and Feet had become independent realms of the senses, no longer alive in coordinate passion. Many know the dissociation of grief—the poet must gather the limbs of Osiris, if they can be gathered at all. (The rendering of the terrible aftermath gives this poem the immediacy of experience, not innocence.) In this autopsy of numbness, the precise sense of “Nerves” is vague because the word was often an amalgam. The meaning draws partly from anatomy, partly from the medical condition (“disordered or heightened sensitivity; anxiety, fearfulness, tension, nervousness.… Freq. in attack of nerves,” OED). The irony endured here is that the nerves have been anesthetized—what would normally carry feeling sit dead as a tomb. Embalmed in the formal hour, they no longer transmit sensation.

The idea of tombs—stolid, mute, imperious—sitting inside the house might be taken as graveyard wit, were the idea not so lurid and Gothic. (Dickens might have made high comedy of the simile.) The scattered nerves have become a crowd of mourners—such a scene could take place only before a funeral. Though the grieving might later return, they’d no longer be obliged to the solemn manners of ceremony.9

This strange vision might have been part of a formal elegy, had Dickinson not directed our attention elsewhere. She could have begun, “After great deaths,” making the funeral arrangements tediously literal. The poem is not a portrait of the hours of mourning but an extended metaphor for the aftermath of an event only alluded to. It’s less an allegory than a mimesis of suffering for the embattled Heart, Nerves, Feet (three cardinal virtues for knight or saint, perhaps). The tableau might be mistaken for the stage set of a morality play. Dickinson forces us to imagine what could have caused a pain so overwhelming that mourning the dead seems the only comparison. Tombs perhaps rose to her mind unbidden, a horror that could not be warded off, because what was dead was hope. And not just hope.

The poet had a particular dread of funerals, as she mentions in a late letter: “When a few years old—I was taken to a Funeral which I now know was of peculiar distress, and the Clergyman asked ‘Is the Arm of the Lord shortened that it cannot save?’ He italicized the ‘cannot.’ I mistook the accent for a doubt of Immortality and not daring to ask, it besets me still.”10

A stiff heart, like the deadened nerves, has lost the living impulse. The OED reminds us that stiff, applied to the body, means “unable to move without pain.” That’s only a short distance from another sense, “rigid in death.” Not long before the poem was written, the noun had passed into slang for a corpse.11 Dickinson was an archeologist of the strata of meaning—the word here absorbs the lesser senses of unbending manners or style without grace. Why not a heavy heart, which would be unable to beat without pain, just alive enough to question? The poet has rescued the cliché by avoiding it, but the phrase goes back at least as far as Venus and Adonis (“Heavy heart’s lead, melt at mine eyes’ red fire!”).12 The reader who heard the suppressed allusion, if it was an allusion, would understand both the condition—Venus longs for death—and Dickinson’s skillful withholding of “lead” until near the end of the poem. The poet was member of a Shakespeare Club at a time when Shakespeare unexpurgated was considered too indecent for women or children.13

What is the heart’s question, however? The usual notion, found in the nuanced reading eighty years ago by Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren in Understanding Poetry (1938),14 is that He must be Christ, that the Heart in pain cannot remember who bore the cross, or when. Yet the revelation must be, not merely that the Heart is bewildered, but that the pain is unbearable. The shock lies in implied recognition, as if the speaker had said, “The pain happened yesterday, but it feels as if I’ve suffered for centuries.”

The interpretation aligns with the standard Christian piety of capitalization; but the ambiguity of syntax festers a bit, since the antecedent of “He” would be absent. In her letters, Dickinson doesn’t capitalize personal pronouns referring to Christ, though in poems she inserts the capital about half the time. Where she personifies “Heart,” however, the pronoun is never capitalized. If her capitals were not accidental, merely inconsistent, the reading must be Christian.

Critics have long been hobbled by the failure of early editors, including Thomas H. Johnson in his variorum edition (1955), or in the reading edition that followed (1960), to include the single quotation marks Dickinson used to set off these questions.15 Though she was perfectly capable of mislaying quotation marks, she didn’t throw them in unwittingly. The direct quotations might have been rendered more clearly,

The stiff Heart questions, ‘Was it He that bore?’

And ‘Yesterday, or Centuries before?’

Like most of her editors, I have kept her single quotations marks. Had the Heart questioned the duration of its own sorrow, the psychology might have been more intense; but then the Heart should have asked, “Was it I that bore?” (R. W. Franklin restored the quotation marks in his now standard edition of her poems [1998].) Still, some sort of amnesia follows the speaker’s fracturing of identity. The measure of devastation, of grief-stricken distraction, is the Heart’s failure to recollect when the major event in Christian faith occurred—or, if that goes too far, then the Heart’s willingness in extraordinary grief, the loss still so fresh, to believe Christ might have died the day before. The loss has canceled the labor of time.

The speaker states, not “My pain is Christ’s,” but “I can think of no pain so severe except His on the cross” or “I feel as if I had been crucified myself.” William Empson remarked in Seven Types of Ambiguity that he “usually said ‘either … or’ when meaning ‘both … and.’ ”16 There are limits, however, to the generosity of ambiguity.

For the zealous, pain is the most aggressive form of devotion. It wasn’t blasphemous for the faithful to believe that in torment they were reliving Christ’s pain—so martyrs consoled themselves. The Heart’s assumption of Christ’s agony is an extraordinary appropriation of Christian myth, especially if, like the speaker, the Heart is female. The speaker gains neither the saintliness of martyrdom nor the assurance of resurrection, only the record of an intensity of anguish beyond measure. It is the condition of great loss always to be immediate.

As so often in Dickinson, the slippery syntax, helter-skelter layering of image, and meanings barely whispered become a powerful method not of statement but, if there were such a word, of suggestedness. (There is such a word, coined by Jeremy Bentham and rarely heard since, except from the mouths of philosophers.) A particular word goes unmentioned here. As it made its way to English through French and Anglo-Norman, “Passion” referred to the sufferings of Christ upon the cross. The use in English for overpowering emotion, the OED reveals, came only late in the fourteenth century, and for love probably only with Spenser. The link is through suffering, not faith—but beneath the suffering, even when the word was only hinted at, ever after lay the veiled pun of romance. There’s a rare romantic acuteness in borrowing the Crucifixion so baldly for the mortal pain of love.

Dickinson was suspicious of the organs of religion. She may have fled Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, where she lasted just a year, because her classmates were so given to proselytizing. (The school ranked the faith of students—Dickinson was among those classed as “impenitent,” pigeonholed with the “No-hopers.”)17 Even at home she was surrounded by those far more pious. The Connecticut River Valley still bore the thunderous inheritance of Jonathan Edwards’s preaching a century before. The poet would have witnessed the decline of the Second Great Awakening in the 1840s and remembered the shock, during the Great Revival of 1850, when many close to her, including her father and sister, had converted to evangelical Christianity. (Her mother had been saved shortly after Dickinson’s birth.)18 “I am standing alone in rebellion,” she wrote.19 Her brother, Austin, followed the others a few years after.20 At school Dickinson could not accept Christ as her savior (“I regret that last term,” she wrote from Holyoke, “… that I did not give up and become a Christian. It is not now too late, … but it is hard for me to give up the world”).21 By thirty she no longer went to church.

Even could the overwrought invocation of the Passion be ignored, the repetitions of pain and paralysis—the ceremonious nerves, the heart in rigor mortis, the mechanical feet, the quartz contentment, the hour of lead—overdo the theatrics to a considerable extent. In reverse angle, however, exaggeration to the point of melodrama expresses the extremity of the speaker’s despair. (One can imagine how the matter would have been handled on the nineteenth-century stage, with weeping and gnashing of teeth.) Though couched in abstraction, the agony is not abstract. Dickinson has presented in four lines an autopsy of traumatic pain—the speaker has become one of the living dead. Such torment is death itself.

STANZA 2

The Feet, mechanical, go round—

A Wooden way

Of Ground, or Air, or Ought—

Regardless grown,

A Quartz contentment, like a stone—

Dickinson apparently suffered a crisis late in 1861, though with a woman so elusive critics might learn more by consulting the shapes of clouds. She was private even within her family. In her thirties she gradually withdrew from company, speaking to rare visitors from the top of the stairs or behind a half-closed door; yet once she’d been eager to join evening society next door at the Evergreens, home of her brother Austin and his wife, Sue, then Dickinson’s closest friend. Stray reminiscences report the delight the poet gave, even in her own kitchen, reciting her poems in a matter-of-fact way.22

What loss could have been so traumatic it would feel like a death, the pain comparable only to Christ’s martyrdom? In April 1862, Dickinson had begun to correspond with Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who had written a lead article in the Atlantic Monthly for young authors, “Letter to a Young Contributor.”23 (As the article was unsigned, it’s unclear how she knew to write “T. W. Higginson. / Worcester. / Mass.”) She asked, “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?”24 Years after her death, he recalled that her handwriting was “so peculiar that it seemed as if the writer might have taken her first lessons by studying the famous fossil bird-tracks in the museum of that college town.”25 She left the letter unsigned, concealing her name on a card slipped into a small envelope. Higginson added, “Even this name was written—as if the shy writer wished to recede as far as possible from view—in pencil, not in ink.”26

Dickinson enclosed four poems. His reply was cautious. “It is probable that the adviser,” he later wrote, “sought to gain time a little and find out with what strange creature he was dealing. I remember to have ventured … on some questions, part of which she evaded … with a naïve skill such as the most experienced and worldly coquette might envy.”27 She had answered, “You asked how old I was? I made no verse—but one or two—until this winter—Sir.”28 This went beyond shyness to the baldfaced lie. By her editor R. W. Franklin’s estimate, she had already finished more than two hundred and fifty poems, having written seriously for four years.29 It would be charitable to imagine that she didn’t consider the earlier work poetry, but more likely she didn’t want Higginson to know she was already past thirty—his article, after all, was for “young” contributors.

Dickinson needn’t have gone further, but what she wrote next was odd:

I had a terror—since September—I could tell to none—and so I sing, as the Boy does by the Burying Ground—because I am afraid—30

Higginson reflected, “The bee himself did not evade the schoolboy more than she evaded me.”31 What “terror” could have been the proximate cause of her poetry? A boy sings (or whistles) past a cemetery to give himself courage, to pretend he’s fearless. (Dickinson’s house, remember, lay not far from a burying ground—from an upper window she could see funeral processions enter the gate.)32 That her mind leapt immediately to the graveyard suggests the near occasion of death—her own, someone else’s, the death of something. There’s no sign, however, that she had been mortally ill or that anyone close to her had died, apart from the first Amherst boys to fall in the Civil War.33

Perhaps she hoped that Higginson would believe her poems incited by some tragic event. Her letters are full of feints and sleights of hand. It’s hard to believe that the “terror,” whatever it was, could be the sole reason she was writing poetry, yet she had no reason to concoct some mortal panic. The closer to truth, the less prone she was to exaggeration:

My Mother does not care for thought—and Father, too busy with his Briefs—to notice what we do—He buys me many Books—but begs me not to read them—because he fears they joggle the Mind.34

For a letter that ignores so much, the bantering surface and wincing coyness cannot hide the resentment, even rage, within.

When a little Girl, I had a friend, who taught me Immortality—but venturing too near, himself—he never returned—Soon after, my Tutor, died—and for several years, my Lexicon—was my only companion.35

Recall her later testimony of unease at what she had taken as the clergyman’s doubts about immortality.

Dickinson can’t always have seen the ambiguities trembling beneath ambivalence. The friend only ventured near—but near to immortality or to Dickinson herself? If the latter, he rejected her. Immortality would be one way to describe a love match—made in Heaven, we say. (She brooded over immortality, Christian immortality, using the word in more than forty poems.) Dickinson doesn’t mean that after the Tutor’s death she was locked in a room with a dictionary, just that she was reduced to words for company. She closed the letter, which had covered so much ground, having cheerfully avoided the direct questions, “Is this—Sir—what you asked me to tell you?”36 Perhaps Higginson had asked how she came to write poetry. Disingenuous might be the word.

It’s unclear how fervent or abiding Emily’s youthful dalliances were, if there were dalliances at all. Her brother and sister both claimed she was no stranger to romance.37 Dickinson had the romantic spirit. A valentine she wrote in 1850, when just nineteen, is flirtatious and high-strung:

Sir, I desire an interview; meet me at sunrise, or sunset, or the new moon—the place is immaterial.… And not to see merely, but a chat, sir, or a tete-a-tete, a confab, a mingling of opposite minds is what I propose to have.… We will be David and Jonathan, or Damon and Pythias, or what is better than either, the United States of America.38

This delightfully giddy manner goes on a long while. After the piece was published in the Amherst College literary magazine, one of the editors remarked, “I wish I knew who the author is. I think she must have some spell, by which she quickens the imagination, and causes the high blood ‘run frolic through the veins.’ ”39 Her identity could not have been much of a secret, as she’d let slip the name of her dog, Carlo, a black Newfoundland who would have been well known to neighbors.40 The favorite candidate for the recipient of this literary skirmish, the first of her publications, is an impoverished Amherst student named Gould.41

There were other possible suitors in her circle—a young man named Newton reading law in her father’s office; an Amherst student named Emmons; and the brothers Howland, one a tutor and the other also reading law with her father—yet little sign, however deeply drawn these friendships, of what hopes she sustained.42 Courtships of the period seem like signals between ships buried in fog. Newton is probably the tutor mentioned to Higginson. After his early death, she called him her “grave Preceptor” as well as an “elder brother.”43 Any romance is unlikely. Her next letter to Higginson, six weeks later, added, “My dying Tutor told me that he would like to live till I had been a poet, but Death was much of Mob as I could master—then.”44 This is a remark about the common life—the missing “as” and the word “mob” without article introduce more confusion than necessary. (This usage was falling out of fashion—Addison had spoken of a “cluster of mob,” and Chesterfield said that “every numerous assembly is mob,” OED.)

Dated probably to the fall of 1862, some months after she wrote Higginson, “After great pain” is one of a clutch of poems that seem—cryptically, elusively—to rake over the coals of an unhappy love affair. The feelings, the nerves, the stiff heart (all in the aftermath of a loss so enormous it seems like death) make it hard to imagine any loss with so great a torment—any loss but love. Speculation among biographers has been drawn almost entirely to two men, but her life is so occluded they are no more than ghosts of possibility.

Returning from the visit to her father in 1855, Dickinson had stopped for two weeks with family friends in Philadelphia.45 It’s imagined that one Sunday her hosts invited her to hear the charismatic minister Charles Wadsworth at the old Arch Street Presbyterian Church. There’s no evidence they met; but Dickinson’s later references to him and a single stiff-necked, undated letter to her—misspelling her last name and responding to what was apparently a request for counsel or consolation—imply that their letters were later destroyed. (After her death, her correspondence was burned, as she desired. This stray, which mentions an “affliction” and her “trial,” as well as her “sorrow,” may have escaped because unsigned. Absence of evidence may be the evidence.)46 Dickinson could be secretive about correspondence—she used two neighbors to forward some of her letters, and a New York couple, possibly, for letters to Wadsworth in the 1870s.47 The latter story came from their granddaughter. Twenty years later, she insisted she “must have made it up.”48

Wadsworth had been devilishly handsome when young, bushy browed though rapidly balding. Called a “new lion” by one of the New York papers, he was compared to Henry Beecher, the most celebrated preacher of the day.49 Wadsworth’s sermons, which read like the worst sort of Christian bombast now, became so wildly popular that a concealed trapdoor, cut through the floor behind the pulpit, let him enter the chancel like some ham actor.50 We know almost nothing of his interest in Dickinson except through letters she wrote after his death to his friends the Clark brothers.51 Though Beecher’s numerous infidelities are an example of pastoral bad behavior, Wadsworth was happily married and lived hundreds of miles from Amherst. He was also sixteen years her elder. He visited Dickinson once in 1860 and again decades later, two years before his death in 1882.52

There’s no reason to believe that Dickinson exaggerated when she claimed to have enjoyed an “intimacy of many years” with him. She called him her “Shepherd from ‘Little Girl’hood” and “My Philadelphia.” Indeed, he may have confided in her—she referred to him as a “Man of sorrow,” a “Dusk Gem, born of troubled Waters,” and said that he was “shivering as he spoke, ‘My Life is full of dark secrets.’ ”53 There is also the curious story, passed down by Martha Dickinson Bianchi, Emily’s niece, that on that trip south Dickinson had “met the fate she had instinctively shunned,” a love “instantaneous, overwhelming, impossible.” After she “fled to her own home for refuge—as a wild thing running from whatever it may be that pursues,” the man followed her to Amherst.54

Unfortunately, there’s no record of such a visit. Parts of Bianchi’s story align with what we know of Wadsworth—that, for example, he moved to the West Coast—but he did not abandon his profession, as she maintained; his departure did not occur a “short time” after meeting Dickinson; and she did not press a woman to name her son Charles. The tale may be family tattle, passed along in mutilated form. (The source was Bianchi’s mother, Sue Dickinson.)55 Still, there’s a hint of something deeper in the poet’s recollection of their final meeting. She was in the garden, she wrote, “with my Lilies and Heliotropes,” when her sister announced a visitor, the “ ‘Gentleman with the deep voice.’ ”

“Where did you come from,” I said, for he spoke like an Apparition. “I stepped from my Pulpit to the Train” was my [sic] simple reply, and when I asked “how long,” “Twenty Years” said he with inscrutable roguery.56

Is this roguery the bantering of an old friend or a confession of regret?

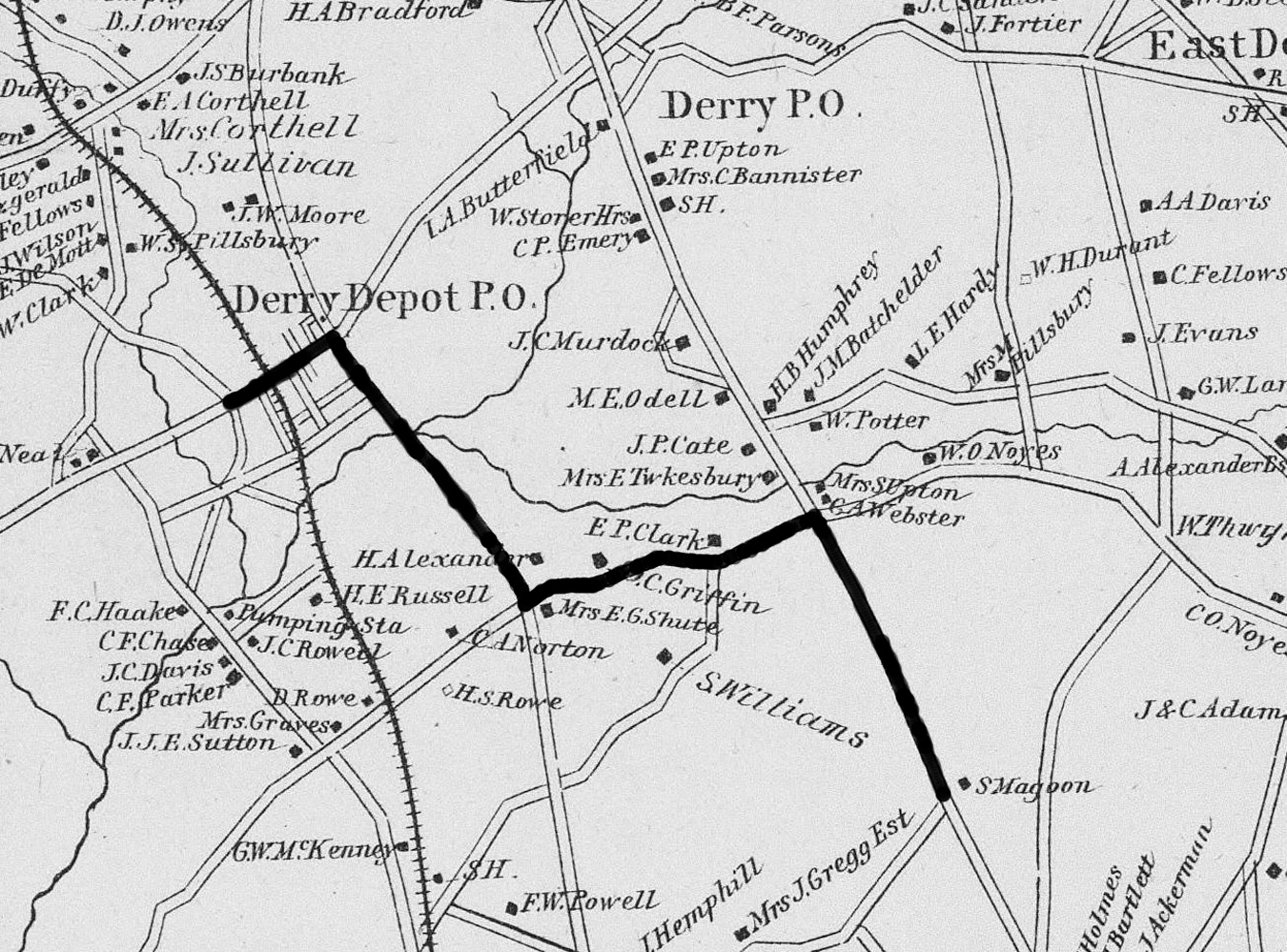

The same month Dickinson wrote Colonel Higginson about her “terror,” Wadsworth answered the call of a Presbyterian church in San Francisco and moved west with his family. If his looming departure caused her alarm, he must have written her the previous September. (Philadelphia papers reported his intention in January—he may have known earlier.)57 That, at least, is the assumption.

There’s a nearer recipient for her affections, Samuel Bowles, editor and owner of the Springfield Republican. Lively, opinionated, apparently inexhaustible, greedy for company, sometime after her brother’s marriage he began regular visits to the Evergreens.58 Eventually he published most of the very few poems Dickinson allowed into print.59

Bowles is a restless, attractive figure, part of a stratum of American nineteenth-century ambition—the go-ahead sort, eager for the fray, intimate with politics, a gregarious and magnetic striver who eventually worked himself to death. His marriage was bitterly unhappy. His wife suffered from various ailments, not all physical—jealous, oversensitive, a bit of a termagant, she made his life a misery.60 That he found solace in spirited conversation with intelligent women no doubt made a wretched bond more wretched. He had many women friends, and there were rumors that a few were more than friends.61

Bowles became a mainstay of Evergreens society before Emily had begun her long withdrawal (“my crowd,” she once called Susan and Austin).62 He was only four years older, though frequently indisposed by his own list of complaints—headaches, insomnia, and sciatica among them.63 In April 1862, as he prepared to sail to Europe for his health, the poet wrote an anxious letter pleading with him, on behalf of the Dickinson coterie, to make a last visit (“Please do not take our spring—away—since you blot Summer—out! We cannot count—our tears—for this—because they drop so fast”). This he did.64 The “terror” could have been his decision the previous September to take the voyage, presuming that she had heard of it.65 When he returned in November 1862, she declared that she could not see him—she was ill, perhaps, or overwhelmed by the prospect. Or he had rejected her. Soon after his return, her private letters to him stopped for a dozen years.66

It was not a complete break or breach, though afterward he came more rarely to the Evergreens—the letter to Austin that heralds his withdrawal is tortured.67 Some fifteen years later, the year before he died, Bowles arrived in Amherst, and Dickinson again refused to see him. He apparently called up the stairs, “Emily, you damned rascal! No more of this nonsense! I’ve traveled all the way from Springfield to see you. Come down at once.” Her sister Lavinia said that she “never knew Emily to be more brilliant or more fascinating in conversation than she was that day.” The anecdote emerged half a century afterward courtesy of a Dickinson cousin, who claimed that Bowles had begun, “Emily, you wretch!” Thomas H. Johnson, however, editor of her correspondence, justified the revision by noting that a letter Dickinson probably sent soon after is signed “Your ‘Rascal,’ ” with a postscript: “I washed the Adjective.”68 Much of what we know about the poet comes filtered through the prejudice and fading memory of others; much of what we know from her is confused, ambiguous, perhaps equally unreliable.

Dickinson and Bowles found each other captivating, though he seems to have been equally taken, or perhaps a bit more, with her sister-in-law. (Town gossip was town gossip.) Over the years Dickinson sent him some fifty poems, most of which he apparently failed to understand; those he published were the most adapted to the taste of the day.69 Her own taste in literature was conservative and often sentimental. She wrote Higginson, “You inquire my Books—For Poets—I have Keats—and Mr and Mrs Browning.” That seems to have been as much Mr. as Mrs., though she apparently adored Aurora Leigh and had a taste for romantic drivel much worse. (It was Mrs. Bowles whom she pressed with a name for her son—but Robert, after Browning, not Charles.)70 She hung a portrait of Mrs. Browning in her room. “You speak of Mr Whitman—” Dickinson wrote as well, “I never read his Book—but was told that he was disgraceful.”71

Any speculation about the poet’s hidden romantic life, if there was such a thing, must inevitably be bound to three letters to the unknown man she addressed as Master, letters found only in draft, two of them much amended and revised. Dickinson apparently roughed out her letters before making fair copies, though few such drafts exist. No doubt most were lost in the holocaust.72

Though it’s not clear that the Master Letters were ever sent, their tone is very like the provocations and insulations of her letters to Bowles. In one of their comic exchanges, he became Dick Swiveller from The Old Curiosity Shop and she the Marchioness.73 It’s worth remembering that the Marchioness was a lowly maidservant who in the end married Swiveller. Franklin, the scholar most schooled in her handwriting, dates the first letter to the spring of 1858, the others to the first half of 1861.74 Though the gradual changes to certain letter forms in her hand may be almost as good as carbon dating, the science is not exact—and even carbon gives only a range.

Critics who thought Dickinson incapable of passion called the letters fantasies. Had they been mere caprices, there should have been clues elsewhere in her work—her imagination was disturbed, but not in quite that way. Reading her poems suggests that, like T. S. Eliot, beneath detachment lay the turmoil of a mind always under intense pressure of the real.

In the second Master Letter, for example, the abject abasement makes uncomfortable reading:

Oh’ did I offend it—Did’nt it want me to tell it the truth Daisy—Daisy—offend it—who bends her smaller life to his <its’>, meeker <lower> every day—who only asks—a task—who something to do for love of it—some little way she can not guess to make that master glad—

A love so big it scares her, rushing among her small heart—75

“Its’” was meant to substitute for “his”—Dickinson sometimes used her pronouns thus, as she does later in the sentence, as well as in a poem dispatched to Bowles and dated by her writing to “about early 1861,” the possible date of this Master Letter. The poem was pinned around a pencil stub and seems to beg him for a word: “If it had no pencil, / Would it try mine— / Worn—now—and dull—sweet, / Writing much to thee.”76 (Dull is a pleasant bit of self-judgment.) The plea—comic, pathetic—hints that he had kept her waiting for a reply.

There is also the extraordinary poem, dated perhaps to the fall of 1862, that opens,

If I may have it, when it’s dead,

I’ll be contented—so—

If just as soon as Breath is out

It shall belong to me—

Until they lock it in the Grave,

’Tis Bliss I cannot weigh—

For tho’ they lock Thee in the Grave,

Myself—can own the key—

Think of it Lover! I and Thee

Permitted—face to face to be—

After a Life—a Death—we’ll say—

For Death was That—

And This—is Thee—77

The anguish, the separation from the lover in life, the fraught wish for love after death—it’s hard not to place such a poem and others like it in the complex of attraction and rejection that forms the Master Letters.

Clues to the recipient are frustratingly ambiguous. In the third letter, however, Dickinson writes, “If I had the Beard on my cheek—<like you> … ”78 Wadsworth, at least in surviving photographs, had no beard. Bowles did.79 There’s another telling reference:

The prank of the Heart at play on the Heart—in holy Holiday—is forbidden me—You make me say it over—I fear you laugh—when I do not see—but “Chillon” is not funny.80

This is not the only time she refers in her letters to the story of the prisoner of Chillon, which she probably knew from Byron’s sonnet and verse tale, very loosely based on the imprisonment of the monk and Geneva patriot François Bonivard. In the tale, when the prisoner is at last released (Bonivard spent four years in a dungeon), he has become so accustomed to his chains, he declares, “It was at length the same to me, / Fetter’d or fetterless to be, / I learn’d to love despair.”81 To Bowles she wrote, in a damaged letter of early 1862, “My Love is my only apology. To the people of ‘Chillon’—this—is enoug[h].”82 Who are these “people”? Others who share her predicament, perhaps, of not wanting freedom from her chains.

Dickinson’s memory of Byron is imperfect. If “people” meant a town, she has forgotten that Chillon was an island castle. Two years later, she wrote her sister, “You remember the Prisoner of Chillon did not know Liberty when it came, and asked to go back to Jail.”83 Byron’s prisoner did not ask to return, but it’s revealing that she recalled the ending that way. If the meaning is clear, that she was a prisoner of love (or had, like the prisoner, “learn’d to love despair”), her distorted memory is touching. Freed, she’d ask to be shackled again. It seems far likelier that Chillon represented that love whose imprisonment she longed not to leave rather than the incarceration suffered when later her eyes went bad; but metaphors, like letters of credit, may be negotiated over great distances.

There’s also the mutilated evidence of that 1862 letter, torn along the edge with the loss of some writing. In both Master Letters that year, Dickinson repeatedly calls herself Daisy, a nickname chosen or given. The letter to Bowles is similarly apologetic, and there she also refers to herself as Daisy—perhaps. Unfortunately, the crucial word is now incomplete: “To Da[isy?] ’tis daily—to be gran[ted].” Richard Sewall, her best biographer, interprets it so (certainly she might have delighted in the grace note of wordplay in Daisy/daily).84 The pencil poem she sent Bowles ended, “If it had no word— / Would it make the Daisy, / Most as big as I was— / When it plucked me?”85 The meaning is almost impenetrable, even after substituting “he” for “it,” as seems necessary in context. Perhaps, very roughly, if he doesn’t write, would she wither like the plucked daisy? Or shrink back to what she was before she was Daisy? Or would he at least make her his boutonnière? Or. Or. (The sexual meaning of “plucked” presumably went unheard, as it had fallen out of use the previous century.)86 The stub of a pencil might be considered a stalk plucked of its flower. The hints are teasing at best—but her intentions might not have been so hidden from him. She writes as if he would understand.

Much depends on the dating of the third Master Letter and the meaning of “Could you come to New England—this summer—could Would you come to Amherst—Would you like to come—Master?” Johnson dated this “about 1861,” which is little help, though by early December Bowles was staying in New York, just outside New England. Franklin redated it to the summer of 1861, months too early for that trip.87 It’s possible that she took so long to mail a fair copy—if one was ever mailed—that she crossed out “summer” in draft because the season had passed. (Dickinson sometimes procrastinated with letters.) On its current dating, the passage might be read to favor Wadsworth.

A number of the poems Dickinson sent to Bowles can be read as explicit confessions of her feelings, especially the poem beginning “Title divine—is mine! / The Wife—without the Sign!”88 It’s not clear that he had the wit to read them so—a man may be a blockhead in such matters, or in kindness pretend to be. Dickinson was not a woman who risked all by saying all. Even so, many poems that year make all but plain that she was devastated by something. She described herself in the second Master Letter, “Daisy—who never flinched thro’ that awful parting—but held her life so tight he should not see the wound.”89

The secret lives of the nineteenth century have never been adequately revealed—we still misread the lack of manifest sign. (It was most of a century after the poet’s death that the torrid infidelity between Austin Dickinson and Mabel Loomis Todd emerged from the shadows.)90 Early writers sometimes thought Dickinson bloodless, immune to anything that stank of emotion. That was the later family view, at least in public.91 Her propriety was worn like her white dress, immortally laundered—but, if Dickinson were not writing in propria persona, she was giving a good imitation. “After great pain” first appeared in Further Poems of Emily Dickinson (1929), subtitled Withheld from Publication by Her Sister Lavinia—that is worth remembering.92 A cluster of poems of similar direction—one probably from 1861, also not published until Further Poems—began, “A wife—at Daybreak I shall be,” and ended, “Master—I’ve seen the face before.”93 Even so, other readings remain possible, or a layering of conflicted readings, as always with a poet with more to conceal than reveal.

Wadsworth lived too far away and was happily married; Bowles may not have known Dickinson until a few months after the first Master Letter—neither problem is insuperable. Critics have made much of the kinship of image and vocabulary between the Master Letters and Wadsworth’s sermons or her letters to Bowles. Each candidate has his passionate advocates. The Master of the first letter and the Master of the others might even have been different men—in her love, at different hours, she might have served different masters. The arguments are circumstantial, the circumstances impossible to reconstruct.

A humdrum explanation for her “terror” has sometimes been proposed, something she would have been more likely to mention to a stranger like Higginson. Two years later, Dickinson suffered prolonged eye-trouble. Her friend Joseph Lyman transcribed a passage from a letter not preserved: “Some years ago I had a woe, the only one that ever made me tremble. It was a shutting out of all the dearest ones of time, the strongest friends of the soul—BOOKS.” She had endured, she reported, “eight weary months of Siberia.”94 That may refer to the first of two long spells of treatment in Boston, each about seven months; but an even earlier attack might have driven her to poetry at the thought she was about to go blind. Recall, though, that this was a terror “I could tell to none.”95 That sounds deeper than eye trouble.

The “terror,” whatever it was, came near the outset of five years in which Dickinson wrote more than half her poems, over nine hundred. (If you drop the hundred or so that can’t be dated by her handwriting, she apparently wrote two-thirds of her poems between 1858 and 1865.) Unfortunately, there’s no evidence of a previous attack—we have nearly forty letters from the seven months after the “terror,” while scarcely two dozen for the more than two years when her eye problems were acute. The poems declined sharply during the attack in 1864 but—if the dating can be trusted—were not much affected by that of 1865. Terror comes in many forms, and the difficulty with her eyes does not foreclose a romantic disaster that provoked the poems linked to pain and parting.

All this is a long way around the barn, but it’s crucial to keep these letters and these shadow relations in mind, even when the difficulties cannot be resolved. Virtually everything in this précis of romantic love can be quarreled with. With her eccentricities, her catastrophic reserve, her niggling and unearthly brilliance, Dickinson was the oddest of odd ducks—her strange manner taxed the patience of acquaintances.

The Master Letters are so personal and specific (one implies that the recipient knew her dog), they were almost certainly written to someone; and we know Dickinson a little better if we consider that both likely candidates were beyond reach. To read her as a woman apart cannot be sustained when the life lies so close to the surface of the words. The modern idea of romantic passion comes from the sufferings of troubadours over a beloved already married. For Dickinson, male and female could easily have been reversed.

FEET

Returning to the second stanza, we’re faced with the extreme condition of Dickinson’s ambiguity. She lived her life in code (a key word in her poems is “circumference”), her equivocations guarding privacies even from those with whom she corresponded. The ambiguities of the poems and letters are of a piece—puzzling then, puzzling still. In the sort of ambiguity familiar to readers, one meaning radiates into suggestive alternatives, or two readings lie superimposed and entangled. In Dickinson’s work, it’s often hard to decipher the central meaning; the reader is left with two, or three, or four equally plausible variations.

Nerves have long been a symbol of bravery, calm in battle, sensitivity; the Heart of steadfastness and love (they’re metonymies of feeling); but Feet are pathetically grounded in the physical. The nerves and the heart, apart from Christian use of the latter, have no place in art except in anatomy texts; but drawing legs and feet was a necessary part of the classical artist’s training—Rembrandt was rare in never learning to paint legs convincingly.

“The Feet, mechanical, go round”—every movement labors here, and what might have been conscious act becomes the numbed motion of the machine. (“Going through the motions” would be the modern phrase, but it was current in Dickinson’s day.) Many machines are rotary in action—something goes round. Dickinson would have seen washing machines and sewing machines and locomotive engines enough. A well-oiled machine is soothing and reliable, but it runs without will or thought or feeling. A poem from the same period, late 1862, begins, “From Blank to Blank— / A Threadless Way / I pushed Mechanic feet— / To stop—or perish—or advance— / Alike indifferent.”96 The numbed condition was on her mind. The lines bear contradictory relation to Tennyson’s “That nothing walks with aimless feet”—Dickinson’s feet have lost sense of purpose. (Tennyson’s poem begins, “Oh yet we trust that somehow good / Will be the final goal of ill.”)97

In the nineteenth century, a mechanic was anyone who worked with his hands—a carpenter or blacksmith, even a manual laborer. Though the meaning later narrowed, there remained the sense, recorded in the OED, that things “mechanical” were vulgar. At the start of the century, the essayist Vicesimus Knox had inveighed against the “literary madness of the trading and mechanical orders”—that is, shopkeepers and laborers who had the insolence to become authors.98 The prejudice further taints the slogging movement, as if the feet were condemned, not just to brute labor, but to labor unworthy. Dissociation preserves but also protects. A life nerveless, stiffened, routine need never be examined—some suffering prevents suffering. There are also irrelevant or subordinate meanings to which syntax makes the lines vulnerable. In English idiom, “go round” means to pay a visit (“I can do no better than go round to Jenny’s,” Bleak House), as well as to travel indirectly or aimlessly (“If they could only go round towards the City Road,” Dombey and Son).99

What on earth is the wooden way? Either the feet go round in wooden fashion, wherever they tread (though we might expect “in a wooden way,” and the feet are unlikely to be both wooden and mechanical), or they take a path made of wood. Boardwalks in cities and towns were still a sign of civic improvement—in 1850 San Francisco, the “sidewalks were made of barrel staves and narrow pieces of board.” There’s no evidence Amherst had plank walks then, but other towns did. Even as late as 1895, they could be found in a similar college town, according to Godey’s Magazine: “From the Bryn Mawr station a boardwalk, which sometimes proves full of pitfalls for the unsuspecting stranger, leads along a level road, past attractive houses.” A few years after Dickinson’s visit, a soldier noted the “old plank walk” that led to Washington’s tomb.100 The combination on that trip of a tomb, a wooden way, and Wadsworth is only a cheerful accident.

The way could be a plank bridge, which lies over ground, or air, or ought—the ought that is a river, say—but it isn’t made of those things. The old plank roads (American plank roads boomed in the 1840s), or a belfry’s plank flooring (where one could walk round the bells), or a house’s porch or floors (many a worrier has paced a room)—all are possible, and none is quite convincing. The wooden way in “I stepped from Plank to Plank” seems to be a pier or a seaside boardwalk.101 (The poem has a furtive relation to “From Blank to Blank.”)

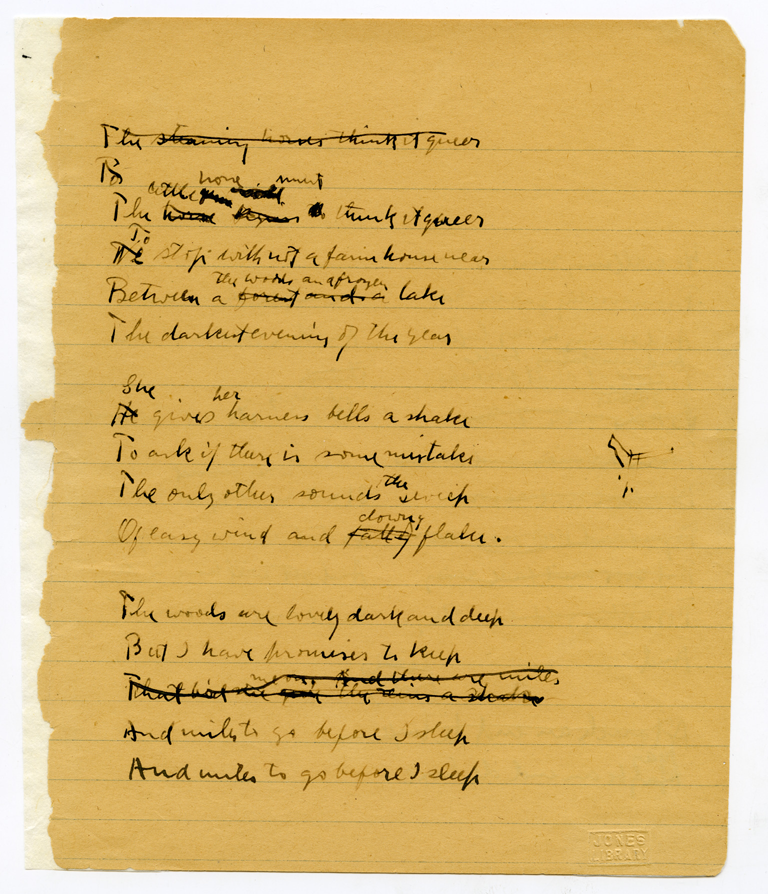

The problem lies in the construction of the passage itself. As it stands in manuscript, the stanza is very odd. The original reads:

1 The Feet, mechanical, go round—

3 Of Ground, or Air, or Ought—

2 A Wooden way

4 Regardless grown,

A Quartz contentment, like a stone—102

Dickinson numbered the first four lines for rearrangement. It’s not clear if she changed her mind as she wrote or simply made a copying error. (Her eye might have caught “Ground” as she wrote “round,” and she just thoughtlessly continued.) To “go round— / Of Ground, or Air, or Ought” is bizarre English, even for Dickinson. There are rare locative uses where “of ” may mean “on” or “in” (OED), but the meaning would still be crippled—and there’s no parallel for this sense anywhere in her work.

Though her punctuation was altered, the first appearance of the poem, in Further Poems, took account of her reordering, rendering the lines as “The feet mechanical go round / A wooden way / Of ground or air or Ought, / Regardless grown, / A quartz contentment like a stone.” (Later collected editions made them, for no good reason, a quatrain with lines ending mechanical/way/grown/stone.)103 Johnson in his influential variorum edition placed the reordered stanza in a footnote, but the poem as printed followed the manuscript.104 Franklin’s now standard edition (1998) transposed the lines as Dickinson directed:

The Feet, mechanical, go round—

A Wooden way

Of Ground, or Air, or Ought—

Regardless grown,

A Quartz contentment, like a stone—

Manuscript of Emily Dickinson, “After great pain, a formal feeling comes.”

Source: MS Am 1118.3 (26c), Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Unfortunately, the corrupt stanza, unhappily the version in Johnson’s one-volume reader’s edition (1960), still appears in anthologies and even critical works.105

The second line of the manuscript stanza (“Of Ground, or Air, or Ought”) disrupts her couplet rhyme, and the whole destroys the quatrain pattern; but Dickinson’s stanzaic forms were frequently irregular, sometimes radically so. (Higginson noticed and did not disapprove.)106 Even reordered, the stanza is difficult to interpret. Critics, if they don’t simply ignore the lines, usually tear out their hair trying to explain what the “Wooden way / Of Ground, or Air, or Ought” ought to be.

The confusion is unnecessary if Dickinson’s directions for recasting the stanza were meant only as an aide-mémoire. The terminal punctuation of the second and third lines might always have been in the right place—it was just the two lines themselves she mixed up. And perhaps while concentrating on her task, realizing something was amiss, she put an unnecessary dash after the first line. She never treated punctuation as fixed, altering it manuscript to manuscript, sometimes bending toward convention, sometimes dashing the poem to pieces. On occasion she misplaced punctuation, but she grumbled only once when a mark was changed in print.107 It was not the least consideration against remaking fair copies willy-nilly that the laid or wove paper she used for her fascicles was expensive.

The numbers clearly mean that the stanza should be recast. If we keep Dickinson’s punctuation in place (removing, for this exercise, the unnecessary dash at the end of the first line, though frequently she interrupted syntax this way), the meaning becomes plain:

The Feet, mechanical, go round

A Wooden way—

Of Ground, or Air, or Ought

Regardless grown,

A Quartz contentment, like a stone—

The wooden way is no longer composed of ground or air or something; rather, on this path the speaker is insensible to anything around her. The stanza could just as easily appear as a quatrain, fully restoring the couplet rhymes and iambic meter.

The Feet, mechanical, go round

A Wooden way—of Ground,

Or Air, or Ought regardless grown,

A Quartz contentment, like a stone.108

Cutting off the list at the end of the line would not be unusual in her work (compare “the sound of Boards / Or Rip of Nail—Or Carpenter,” “Of Amplitude, or Awe— / Or first Prospective—or the Gold”).109 Dickinson was not beyond breaking her lines for emphasis, however, or shortening or lengthening her meter. In the irregular version, however, sense perhaps more gracefully follows the line, which seems her intention.

One of the main uses for “wooden way” just before Dickinson’s day was for pre-steam railways, which often ran on wooden rails.110 There’s another possibility. Riddles occupied many a parlor of an evening—“What is a wooden way of ground, or air, or ought?” might at that day have been answered, “Treadmill.” (More than one critic has already suggested this.)111 The mode of punishment later suffered by Oscar Wilde was constructed as a paddle wheel set above the ground but, because each step was open, above air as well. It was the endless staircase that, for many prisoners, led only to death. Introduced in some New England prisons in the 1820s, it proved inefficient at milling grain or pumping water.

The treadmill would expose the speaker’s sense of being punished—she must serve her sentence. (The Crucifixion was a punishment.) It would be pretty to think that a buried pun on “sentence” would have occurred to Dickinson, given the patched-together, dash-happy nine-line extravaganza with which the poem ends. The poem never achieves release—it ends on an interminable dash, a continuation not quite declared an ending. Such a sentence can never be outlived—surely the aftermath of a death feels that way. The idea is too ingenious, unfortunately, like the notion, pursued by Helen Vendler among others, that the disordered stanza reveals a disordered mind.112

None of this can tell us for certain what Dickinson intended by the “wooden way.” Through the nineteenth century the phrase could also mean a bridge approach, a track leading from the ground to scaffolding, and, after her death, more than one type of elevated railway. Indeed, there’s a thin chance that she employed the word as a synonym for “wooded” (this American usage persisted only through the nineteenth century) and that the wooden way is no more than a path through woods. The business of the stanza is to show the speaker, in the stupor of grief, reduced to an automaton walking she knows not where. It’s to the credit of critics that none, so far as I know, has imagined the great pain as merely physical—say, that of a broken leg.

Dickinson often had some ground for her metaphors, but the shadows of her poems lie in the guilts of ambiguity or in simply not caring how easily the reader might be led astray. If her private readers made her aware of the snarls and tangles, they were not snarls and tangles she chose to unravel. (She sent very few friends, only half a dozen or so, more than a handful of poems.)113

“Ought” is the variant spelling of “aught,” that is, “anything whatever.” Given the license of Dickinson’s language, there’s the sidelong possibility that in punning fashion she meant the noun “ought,” duty or necessity (George Eliot, “The will supreme, the individual claim, / The social Ought” [1874]; and Gladstone, “The two great ideas of the divine will, and of the Ought, or duty” [1878], OED). I’d dismiss this as a stray implication if the poem didn’t seem a little short of duty but a little long on necessity. Within the mist of such metaphors, there are shapes but no clear figures. About the best one can hope for with Dickinson’s metaphors is to establish a range or grid of potential meaning within which the real meaning has been embedded. Dickinson hedged her meanings, but hedging at times reveals more than clarity, just as her revisions show the movement of mind toward the opacities of brilliance: in “Blazing in gold and quenching in purple,” the “kitchen window” became “oriel window” and at last “Otter’s Window.”114

Presumably it is the Feet that have grown regardless, personified like Heart and Nerves, embodied though only fractions of the body. Distracted, unconscious of walking but still walking, they have fallen into the contentment of the inanimate. An underlying meaning of “regardless,” just passing out of fashion, was “slighted; not worthy of regard”—that would be an attractive whisper of meaning, even were the other ascendant.

QUARTZ

Ceremonious nerves, stiff heart, mechanical feet grown regardless of their path—the benumbed state of grief is summed in two metaphors: “Quartz contentment, like a stone” and “Hour of Lead.” As a girl, Dickinson had studied geology at Amherst Academy, which she entered aged nine. Students of the academy were allowed to attend lectures at Amherst College, including those by one of the eminent geologists of the day, the Reverend Edward Hitchcock. (Harriet Martineau saw the young girls there some years before Dickinson was a student.)115 A copy of his textbook Elementary Geology, which became one of the most widely adopted, lay in the family library. It was also, perhaps unsurprisingly, the geology book assigned at Mount Holyoke.116 Though she didn’t stay long enough to take up the subject there, Dickinson did write her brother—it shows her bristling enthusiasm for the sciences—that she was “engrossed in the history of Sulphuric Acid!!!!!”117 Hitchcock’s influence appears in later poems like “On a Columnar Self.”118

Dickinson knew enough geology to realize that quartz is a crystal, not a stone; but “quartz stone” was a phrase often used, and Hitchcock repeatedly refers to “quartz rock.”119 Some varieties are considered semiprecious gemstones, and pure quartz is almost as hard as hardened steel. The contentment, then, would be obdurate—but perhaps like pure quartz translucent or transparent, easy to see into.

To press the reading further, and even too far, “Quartz contentment” is a striking metaphor for feeling crystallized within. Of all the minerals, Dickinson chose the one then considered, by Hitchcock among others, the most common (in fact, feldspar predominates).120 When the quartz crystal stops growing, it has reached a state of what might be called contentment—frozen at least metaphorically—but that contentment is a hard, beautiful thing without feeling. “The Dew— / That stiffens quietly to Quartz,” she wrote in another poem, within days or weeks, the word’s only other appearance in surviving poem or letter.121 Lost in the subterranean arguments and silent treaties of language, “Regardless grown” almost becomes the promise fulfilled in grown quartz—just as a spire of quartz crystal might, by its resemblance to an icicle, prepare the frozen death to come.

The main ingredient of sand, quartz glitters—indeed, the unmentioned glittering may anticipate the snow implicit in the ending. A snowflake, too, is a crystal. In Dickinson’s day, contentment could mean, not just ease of mind, but the very action of becoming satisfied, a meaning later lost (Arthur Helps, “With no contentment to the appetites of the hungry” [1851], OED). The flicker of appetite would be disturbing. The metaphor marks the speaker’s ruthless patience, with perhaps a touch of fatalism. A stone has the capacity to wait without change, for eons if necessary. (It would be wrong to assume that contentment requires passivity—a quartz contentment could be read as the grip of obsession, or of near madness.)

Dickinson’s contentment was rarely content. There is, not just “Tell it the Ages—to a cypher— / And it will ache—contented—on” (“Bound—a trouble”), and “A perfect—paralyzing Bliss— / Contented as Despair” (“One Blessing had I”), but more disturbingly “A nearness to Tremendousness— / An Agony procures— / … // Contentment’s quiet Suburb— / Affliction cannot stay / In Acres” (“A nearness to Tremendousness”).122 Contentment can be a frozen despair, a serenity not the least serene.

STANZA 3

This is the Hour of Lead—

Remembered, if outlived,

As Freezing persons, recollect the Snow—

First—Chill—then Stupor—then the letting go—

The machine-like walk is the first hint of the circumstance of the last stanzas—a death march through extreme cold, the body on automatic, numbed within and numb without, mechanical because near exhaustion, moving because stopping is sleep and sleep is death. (“Death march” was a phrase first found in this sense less than two decades before; as the alternative to “dead march,” the march of a funeral procession, it had been in the language for a century [OED].) It’s as if Dickinson remembered the cold before the poem could mention it. Had she been recalling the town tomb, she was already thinking of frozen bodies.

If “Quartz contentment” summarizes the plodding of the feet (meditation by walking in circles is not uncommon), the “Hour of Lead” is the collapsed figure for the state of grief that governs the poem—it returns to formal feeling with a vision of the dull, inertial aftermath of trauma. Apart from uranium, lead is the heaviest naturally occurring element. (Though discovered by a chemist at the time of the French Revolution, uranium had little use beyond glassmaking or photography until the twentieth century—it went unmentioned in Hitchcock’s Geology.) “Heavy as lead” is a phrase at least as antique as Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy (1621).123 The heart or soul “as heavy as lead” was a customary formula.

Shakespeare took the qualities of the metal beyond the heartsick metaphor in Venus and Adonis. “Like dull and heavy lead” (Henry IV, Part II) and “Is not lead a metal heavy, dull, and slow?” (Love’s Labour’s Lost)124 are confirming instances of the mental dullness and heavy-footed pace intimate with the Hour of Lead. “Leaden”—what is the Hour of Lead but leaden?—has an acute semantic range here, as the OED reminds us: “heavy, dull, benumbing,” and, of the limbs, “hard to drag along.”

It’s no more than an amusing coincidence, given the possible connection to the Master Letters, that the next line in Love’s Labour’s Lost is “Minime, honest master, or, rather, master, no.” The exchange is part of an elaborate quibble between Don de Armado and his page, Moth. There’s a slow-gaited ass, a message to be delivered, and a promise to be “swift as lead”—when his master remonstrates, Moth replies, “Is that lead slow which is fir’d from a gun?” Recall the third Master Letter—“If you saw a bullet hit a Bird …” The reader can cut too deeply, but—whatever connection to Shakespeare, little or none—the lines remind us that any mention of lead may bring up bullets, and that Dickinson, no mean quibbler herself, was perfectly capable of thinking of hardness and perhaps translucency when she wrote “quartz” and then heaviness and stupor, or perhaps brute violence, when she thought of lead. She began a poem, “My Life had stood—a Loaded Gun.”125

I FELT A FUNERAL

Months before, probably, Dickinson had written what may be a trial piece.

I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,

And Mourners to and fro

Kept treading—treading—till it seemed

That Sense was breaking through—

And when they all were seated,

A Service, like a Drum—

Kept beating—beating—till I thought

My mind was going numb—

And then I heard them lift a Box

And creak across my Soul

With those same Boots of Lead, again,

Then Space—began to toll,

As all the Heavens were a Bell,

And Being, but an Ear,

And I, and Silence, some strange Race

Wrecked, solitary, here—

And then a Plank in Reason, broke,

And I dropped down, and down—

And hit a World, at every plunge,

And Finished knowing—then—126

“After great pain” appears here in nascent form, or rather through the looking glass. Both open with a funeral—something has died. We have mourners eventually “seated” versus nerves that “sit ceremonious,” “treading—treading” versus the mechanical feet, “My mind was going numb” versus “Chill—then Stupor,” “Boots of Lead” versus “Hour of Lead,” “Plank in Reason” versus “Wooden way,” and Brain and Ear versus Nerves and Heart. “Dropped down” and “Finished knowing—then” become “Stupor—then the letting go.” Even the critical appearance of “then” betrays a similarity of dramatic construction. There are differences—the mechanical round of the wooden way is enacted in the earlier poem by the relentless ands, a baker’s dozen of them (an anaphora of them, as it were). Half the lines start there, emphasizing the leaden treading and the beating, beating of the funeral service.

The images form a cluster like those in Shakespeare: funeral, mourners, treading, sitting, parts of the body, numbness, silence, lead, solitude, obliteration—and perhaps even verbal echoes like “Wrecked” / “recollect.” (Shakespeare’s clusters are more disconcerting and almost irrational—dogs and candy, for instance, and geese, disease, and bitterness.)127 Though Dickinson’s images derive mainly from the trappings of a funeral, the echoes can’t quite be argued away—her funerals lack a preacher, for instance. The elements of “After great pain” are not exact equivalents—“Hour of Lead” is not “Boots of Lead”—but when lead is invoked, for example, walking or treading lies near. (The latter phrase has some age to it. William Drummond of Hawthornden wrote an epigram about Charles I that included the line “In boots of lead thrall’d were his legs.”)128

There’s a similar cluster in a poem written late in 1862, “A Prison gets to be a friend,” a poem so infused by “The Prisoner of Chillon” it might have been spoken by the prisoner himself. There are parts of the body (“face,” “Eyes,” and, amusingly, the “Cheek of Liberty”); “Content” versus “Quartz contentment”; and, most tellingly, “We learn to know the Planks— / That answer to Our feet,” the image of the prisoner circling in his cell, a “Demurer Circuit— / A Geometric Joy” (later, “The narrow Round—the stint— / The slow exchange of Hope”).129 Perhaps the “Wooden way” also had intimations of such a circuit—certainly that phrase and the “Plank in Reason” have some association with imprisonment and loss of hope. The dominant feeling is loneliness and the passive acceptance of hard fate.

Return to “I felt a Funeral.” “I heard them lift a Box”—this must be a coffin, a “box of boards,” as Dickinson wrote in a letter that year.130 The old euphemism was frequently heard in the nineteenth century. (A Gold Rush miner wrote in 1849, “They take a poor fellow when he does happen to die, and put him in a rough box, clothes and all, and chuck him in a hole.”)131 “Box” was not pure slang, as the OED has it, but figurative at times for a lowly coffin resembling a long packing crate—at times it was a packing crate. Dickinson’s use of the word may therefore be calculated—there’s more of the plain terror of death in being pitched, like candles or twists of tobacco, into a miserable box. The poem, like “After great pain,” is about a loss that drives the speaker nearly mad—the cause is likely the same.

The mourners tread in the brute, steady way of mechanical feet. They sit during the service, where the words batter the speaker into numbness. Do they beat like the drum of a dead march? As pallbearers, the mourners lift the coffin and walk across her soul in their “Boots of Lead.” The heavens toll like a church bell, probably the slow, steady knell of the funeral bell. All being becomes just a passive state of listening, of being forced to hear. The speaker and Silence are shipwrecked (Dickinson usually uses “wrecked” of shipwrecks), a “strange Race” together—it’s hard not to see an allusion to Robinson Crusoe here. Are they “strange” because they do not speak in a world where everyone else can’t stop talking, or because she is now so estranged from the living? Her growing discomfort with company is perhaps shadowed here.

The speaker is not describing her own funeral—the funeral is “in my Brain.” Still, great loss makes the living feel that something inside has died. The poem may be a literal version of the idea. When the mourners tread across her soul (Dickinson originally wrote “across my Brain,” probably forgetting she had used the word in the opening line), that is all figurative—but the poet writes as if someone had just walked over her grave. Again, the line seems the literal version of a commonplace. The shuddering in the usual phrase goes back at least to Swift.132 There is a death to answer a death.

Should we be reminded of that nineteenth-century horror, being buried alive? Poe was obsessed by the idea. His stories “The Premature Burial” and “The Fall of the House of Usher,” among others, are the most famous examples; but the fear was widespread. Dickinson once wrote Higginson, “Of Poe, I know too little to think”133—but that doesn’t mean she knew nothing. The line, as so often, is cunningly evasive.

The horror of life in death lies not far from the death in life beneath both poems. Dickinson continued, after her remark on Poe, “Hawthorne appalls, entices.” Did she know “The Minister’s Black Veil” from Twice-Told Tales (1837),134 where a village parson appears one Sunday in a black veil, causing consternation among his congregation and leading his betrothed to break their engagement? He continues to wear it all his life, refusing to remove it even at the point of death. The Recluse, as Bowles once called Dickinson, might have had a moment of recognition—of enticement—after being appalled. She wrote a poem about a veil, after all, that opens, “A Charm invests a face / Imperfectly beheld— / The Lady dare not lift her Vail / For fear it be dispelled.”135 Reticence has its responsibilities.

Reason breaks down, but where is the “Plank in Reason”? Is it just an imaginary plank across the great reach of the Heavens? Cynthia Griffin Wolff, in her biography of Dickinson, offers a telling emblem from the book Religious Allegories (1848), showing a gentleman crossing a plank that bestrides a dark abyss. The man holds a radiant book that must be the Bible, the plank is carved with the word “FAITH,” and a shining mansion awaits his crossing.136 Dickinson’s “Plank in Reason” would be quietly critical. Other senses of “plank” seem not to apply.

If the speaker feels buried, is the plank the bottom of a board coffin from which her corpse plummets into whatever realms lie below? “And Finished knowing—then—”: the speaker vanishes into unknowing and the poem ends in dissolution, just as “After great pain” ends in … in nothing. Dickinson considered changing “Finished” to “Got through” but perhaps felt the ambiguity would have promised survival.137

FREEZING

The last line of “After great pain” is a death not quite death. “If outlived” introduces the species of doubt that secures the magnitude of pain. The effects of extreme cold were familiar—Dickinson’s knowledge of death by freezing could have come from many sources. There may have been some local incident (Samuel Bowles suffered severely from sciatica after a harrowing sleigh ride to Amherst early in 1861);138 but, throughout this period, there are scenes in tales like “The Christmas Letter” from Godey’s Lady’s Book (1856):

She is so very weary, and the stupor is returning. So, feebly brushing off the snow from a felled tree lying by the wayside, she sits down. She grows colder, more lethargic, more numb; minute by minute goes by, yet still she sits. She is just sinking into unconsciousness.139

The most notorious incidents of freezing to death, however, occurred half a century before on the retreat of the French army from Moscow and more recently during the Arctic expeditions.

In The United States Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin (1854), Elisha Kent Kane, who served as ship’s surgeon to the first Grinnell Expedition, quoted from his own “scrap-book”:

“I will tell you what this feels like, for I have been twice ‘caught out.’ Sleepiness is not the sensation. Have you ever received the shocks of a magneto-electric machine, and had the peculiar benumbing sensation of ‘can’t let go,’ extending up to your elbow-joints? Deprive this of its paroxysmal character; subdue, but diffuse it over every part of the system, and you have the so-called pleasurable feelings of incipient freezing. It seems even to extend to your brain. Its inertia is augmented; every thing about you seems of a ponderous sort; and the whole amount of pleasure is in gratifying the disposition to remain at rest, and spare yourself an encounter with these latent resistances. This is, I suppose, the pleasurable sleepiness of the story books.”140

Can’t let go. Here is the numbness of the “formal feeling” and “Hour of Lead,” here the incipient freezing, the inertia of the mechanical feet (“Regardless grown”) and “Quartz contentment” and “Hour of Lead.” Here, in short, is the memory of someone freezing to death. Kane is adamant that the feeling is not sleepiness—and nowhere does Dickinson mention sleep. This may be the very passage that informed the poem, the details reworked, perhaps even the “letting go” suggested by the bizarre tingle of the “magneto-electric machine.”

Kane had prefaced the account by saying, “I felt that lethargic numbness mentioned in the story books.” I’ve been unable to find any book that answers the surgeon’s reference: Frankenstein (1818) will not do, nor Symzonia (1820), nor The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym (1838).141 Perhaps The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798/1834) comes closest among imaginative speculations about the frozen north or south, with “The ice was here, the ice was there, / The ice was all around,” the “Night-mare Life-in-Death,” and the “gentle sleep” the Mariner enjoys. At times Coleridge approaches Dickinson’s own nightmarish vision. When the Mariner wakes, he recalls,

I moved, and could not feel my limbs:

I was so light—almost

I thought that I had died in sleep,

And was a blessed ghost.142

The numbness is there, and the fall into sleep that may be a falling out of life; but the connections are weak.

“Storybook” had increasingly come to mean a collection of children’s stories. There are tales of the cold in Grimm and Andersen, but none relevant to Kane’s memory. One novel within range is Fenimore Cooper’s Sea Lions (1849), toward the end of which a man almost freezes to death in the snow. His companions rub his limbs and give him a dose of brandy, followed by coffee:

After a swallow or two, aided by a vigorous friction, and closely surrounded by so many human bodies, the black began to revive; and the sort of drowsy stupor which is known to precede death in those who die by freezing, having been in a degree shaken off, he was enabled to stand alone.143

Drowsy stupor. But perhaps we don’t need to know what books or stories Kane referred to. He recorded in Arctic Explorations (1856) his later experiences leading the second Grinnell Expedition:

I was of course familiar with the benumbed and almost lethargic sensation of extreme cold; and once, when exposed for some hours in the midwinter of Baffin’s Bay, I had experienced symptoms which I compared to the diffused paralysis of the electro-galvanic shock. But I had treated the sleepy comfort of freezing as something like the embellishment of romance. I had evidence now to the contrary.144

The “embellishment of romance” suggests that he wasn’t thinking of children’s stories. Two of his men “came begging permission to sleep”:

Presently Hans was found nearly stiff under a drift; and Thomas, bolt upright, had his eyes closed, and could hardly articulate.… The floe was of level ice, and the walking excellent. I cannot tell how long it took us to make the nine miles; for we were in a strange sort of stupor, and had little apprehension of time.145

Benumbed, lethargic, extreme cold, diffused paralysis, sleepy comfort, freezing, stupor. Emily’s father’s copy of the 1857 printing of Arctic Explorations was in the Dickinsons’ library.146 This immensely popular book stayed in print for half a century and eventually sold over 150,000 copies.147 If Dickinson were not recalling Kane’s first book, the second would have done—and perhaps she knew both.

A lost traveler making endless circles appears in Charles Francis Hall’s account in Arctic Researches and Life Among the Esquimaux (1865) of the search for a lost shipmate: “The tracks turn again in a circle. Now they come in rapid succession. Round and round the bewildered, terror-stricken, and almost frozen one makes his way.”148 Such aimless circling is much like that of the prisoner in his cell. During the 1860s, references in her poems to the polar regions show that the poet had read of the search for Sir John Franklin. The lines “When the lone British Lady / Forsakes the Arctic Race” (in “When the Astronomer stops seeking”) refer to the end of Lady Franklin’s search for her husband.149 In “Through the strait pass of suffering,” Dickinson makes the expeditions north a figure for suffering martyrs (“The Martyrs—even—trod”), intent to the point of death on their search for grace:

Their faith—the everlasting troth—

Their expectation—fair—

The Needle—to the North Degree—

Wades—so—thro’ polar Air!150

The “even—trod” through the “strait pass of suffering” echoes the numbing round of the feet in “After great pain,” as well as Christ’s journey through the Stations of the Cross. Dickinson sent this poem to Bowles, adding meaningfully, “Because I could not say it—I fixed it in the Verse.”151