ARROYO TOAD

Bufo californicus Camp 1915

Arroyo toad, Baja California, Mexico. Courtesy of Rob Schell Photography.

Status Summary

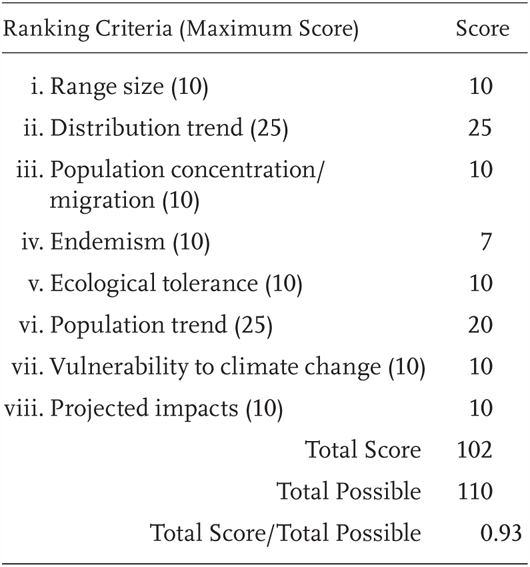

Bufo californicus is a Priority 1 Species of Special Concern, receiving a Total Score/Total Possible of 93% (102/110). During the previous evaluation, it was also considered a Species of Special Concern (Jennings and Hayes 1994a), and it has been listed as federally Endangered since 1995.

Arroyo Toad: Risk Factors

Identification

Bufo californicus is a small to medium-sized (4.6–8.6 cm SVL), light-gray to tannish-brown toad that often has some greenish or olive and dark-brown mottling on the back and sides (Camp 1915, Stebbins 2003). The underside is buff or dirty white and usually unmarked (Stebbins 2003). A light middorsal stripe is rarely present (Jennings and Hayes 1994a, Stebbins 2003). Weak cranial crests are often present and the paratoids are oval-shaped and widely separated (Stebbins 2003). The advertisement call of this species is a musical trill that lasts 3–10 s. The pitch of the call rises quickly and is held constant for the remainder of the call, which ends abruptly (Stebbins 2003, Elliott et al. 2009). Like most toads, the tadpoles are small and black early in life. However, several weeks post-hatching they develop a cryptic tan coloration that closely matches the substrate (Sweet 1992, Hancock 2009).

Metamorphosed individuals of this species may be confused with the western toad (B. boreas), which is the only sympatrically occurring toad. Bufo boreas has a prominent white or cream dorsal stripe and lacks cranial crests (Stebbins 2003). Young tadpoles that still retain the black coloration are difficult to distinguish from B. boreas, but older tadpoles are readily distinguishable.

Taxonomic Relationships

Until recently, Bufo californicus was considered a subspecies of the Arizona toad (B. microscaphus) (Price and Sullivan 1988), although recommendations to recognize it as a full species date back to Myers (1930). Frost and Hillis (1990) recognized this species as distinctive based on the general observation that few allopatrically distributed polytypic species represent single genetically cohesive units, as is implied by retaining B. californicus as a subspecies under B. microscaphus. Later analyses of allozyme data confirm that B. californicus is a distinct lineage, providing support for its recognition as a full species (Gergus 1998). Additional analyses of advertisement calls indicated a substantial amount of variation within the species complex, although the results were equivocal with respect to species status (Gergus et al. 1997). Lovich (2009a) analyzed data from two mitochondrial genes and found additional evidence that B. californicus is a distinct species. This work also identified clades within B. californicus that roughly correspond to parts of the range north and south of the Los Angeles Basin, respectively.

Frost et al. (2006a) recommended placing this species and many other North American bufonids in the genus Anaxyrus, although this proposal and the analyses that support it are controversial (Crother 2009, Frost et al. 2009a, Pauly et al. 2009). We choose not to follow this recommendation at the present time, pending further analyses, and to maintain taxonomic stability.

Life History

Bufo californicus is primarily nocturnal and feeds predominantly on nocturnally active ant species (Cunningham 1962, Sweet 1992, Sweet 1993, Mahrdt et al. 2002). Adults typically emerge from retreats approximately 30–40 min after sunset, remaining active down to temperatures of around 13°C on dry nights and 10°C on rainy nights, with nocturnal activity increased during wet periods (Cunningham 1962, Sweet 1992, Sweet 1993).

Males begin calling at varying times of the year depending on local conditions and elevation, although calling activity appears to initiate when water temperatures reach or exceed 11–13°C (Myers 1930, Sweet 1992). Choruses generally begin in late February in coastal populations and late March or April at higher elevation inland sites, and they may continue into July (Sweet 1992, Sweet 1993, Stebbins 2003, Hancock 2009). Eggs are laid near the male’s calling site on a substrate of mud, sand, or gravel, away from vegetation and other submerged debris (Sweet 1992). Hatching occurs after 4–6 days at typical water temperatures (12–16°C), although the larvae remain associated with the egg mass for an additional 5–6 days. Metamorphosis can occur in as few as 65 days, although typically 72–80 days are required (Sweet 1992, Hancock 2009). Larger males and females are more sedentary and tend to breed in the same pools throughout the reproductive season and from year to year (Sweet 1993, Hancock 2009, Mitrovich et al. 2011). The seasonal activity period for adults extends roughly from the beginning of the breeding season to late June or July, after which most toads become inactive (Cunningham 1962, Sweet 1993, Hancock 2009). Juveniles may remain active into October or later following rains (Sweet 1993).

Bufo californicus usually attain reproductive condition in their second (males) or third (females) year. The species is relatively short-lived, with few toads living beyond 5 years of age. In the absence of nonnatural disturbances, survivorship of adult toads is high during the active season, but decreases markedly during the inactive season. Sweet (1993) documented that toads experience ∼55% per year mortality mostly during the winter, though other estimates suggest even higher mortality (D. Holland and N. Sisk, unpublished data, reported in Sweet and Sullivan 2005). Eggs and young larvae are apparently unpalatable to most predators, although garter snakes and nonnative fishes prey upon older tadpoles (Sweet 1992). Juvenile toads that have not yet adopted the nocturnal activity pattern characteristic of adults also experience high predation pressure (Hancock 2009). Adult toads experience intense predation from introduced bullfrogs in areas where that species occurs (Miller et al. 2012, R. Fisher pers., comm.). In the absence of bullfrogs, adult toads experience much lower predation intensity (Sweet 1993, Hancock 2009).

Habitat Requirements

Along with its close relative Bufo microscaphus, B. californicus may have the most specialized habitat requirements of any North American anuran (Stebbins 2003). This species requires shallow, slow-moving stream and riparian habitat. In some areas they may occupy first-order streams, although most populations inhabit second- to sixth-order streams that have extensive braided channels and sediment deposits of sand, gravel, or pebbles that are occasionally reworked by flooding (Sweet and Sullivan 2005). These toads will use either permanent or seasonal streams, although seasonal streams must flow for a minimum 4–5 months for successful reproduction and recruitment (Sweet and Sullivan 2005). At inland sites, radiotelemetry studies indicate that this species rarely moves beyond the immediate upland margin of streams, although in coastal sites arroyo toads appear to occasionally use and disperse across hotter and drier upland sites (Sweet 1992, Sweet 1993, Griffin and Case 2001, Hancock 2009, Mitrovich et al. 2011). Mitrovich et al. (2011) found that radio-tracked toads actively selected channel and terrace stream habitats, and largely avoided surrounding scrub, grassland, and forest. On average, males were found in closer proximity to flowing sections of stream than females, possibly to maximize reproductive opportunity (Mitrovich et al. 2011). Bufo californicus is known to occasionally use and breed in human-made habitats, such as artificial stream terraces and ponds (Price and Sullivan 1988, Mahrdt et al. 2002). It is unknown whether the species can persist in these habitats.

Distribution (Past and Present)

Bufo californicus historically occurred in coastal drainages from the San Antonio River, Monterey County, California, southward through the Transverse and Peninsular Ranges to the vicinity of Arroyo San Simón in Baja California Norte, Mexico (Price and Sullivan 1988, Gergus et al. 1997, Grismer 2002, Lovich 2009a). Almost all populations occur along the coast or on the coastal slopes of the southern California mountains. Six localities were previously recognized from the desert slopes of Los Angeles, Riverside, San Bernardino, and San Diego Counties, California (Patten and Myers 1992, Jennings and Hayes 1994a). Desert slope populations are known to occur at Little Rock Creek, Los Angeles County, and the Mojave River, San Bernadino County. Populations at Whitewater River, Riverside County, Borrego Springs (listed as San Felipe Creek in Jennings and Hayes 1994a), Vallecito Creek, and Pinto Canyon, San Diego County, are probably in error and are the result of misidentifications (Ervin et al. 2013). The known elevational range extends from near sea level to approximately 1000 m (Stebbins 2003; S. Sweet, pers. comm.).

The present distribution of B. californicus is considerably smaller than it once was. Jennings and Hayes (1994a) estimated that this species had disappeared from 76% of its former range in California, although more recent estimates place this loss at 65% (Sweet and Sullivan 2005).

Trends in Abundance

In addition to the extirpations discussed above, extensive declines in abundance have been documented in most Bufo californicus populations that do survive. Extensive collections from the 1930s, largely stemming from the work of L.M. Klauber, suggest that this species was formerly present at much higher densities (S. Sweet, pers. obs., reported in Sweet and Sullivan 2005).

Nature and Degree of Threat

A recent 5-year review of the status of Bufo californicus thoroughly discusses the ongoing threats to this taxon (USFWS 2009). We follow the findings of that document and recommend that readers consult it for additional detail.

The greatest threat facing this taxon is loss and degradation of habitat that stems from modifications to hydrology from reservoir construction, roads, flood control, development, recreational activity, and mining (USFWS 2009). In addition, declines are occurring even in areas that are not subject to development and direct habitat degradation from human activities (Hancock 2009). These additional declines stem largely from introduced predators (primarily bullfrogs and green sunfish) and introduced plants, which degrade habitat and/or decrease survivorship of toads (Sweet 1992, Hancock 2009, USFWS 2009, Miller et. al. 2012). Off-highway vehicle use has also caused both habitat degradation and direct mortality in this species (Ervin et al. 2006)

Status Determination

Major declines in both distribution and abundance, coupled with several ongoing threats, combine to warrant a Priority 1 Species of Special Concern status for Bufo californicus.

Management Recommendations

Management efforts for Bufo californicus should mirror those outlined by the USFWS recovery plan and 5-year review for this taxon (USFWS 1999, USFWS 2009). The recent 5-year review suggests that management efforts to date have been effective, and the outlook for this species has improved somewhat since it was initially listed (USFWS 2009). The most important management strategy is to preserve existing stream habitat that supports this species and to restore additional habitat that can support self-sustaining populations. Restoration efforts should include dam removal to allow streams to meander and rebuild sand and gravel bars, and removal of exotic plants and vertebrate predators.

Monitoring, Research, and Survey Needs

Monitoring, research, and survey needs are covered in depth in the USFWS recovery plan for this taxon and the recent 5-year review. We refer the reader to these documents for additional detail (USFWS 1999, USFWS 2009). Monitoring efforts should focus on recovering populations, particularly those in newly restored habitat. It is particularly important to continue monitoring through drought and El Niño cycles given that this is a short-lived species and several years of consistent drought could be extremely damaging to recovering populations.

In addition, research aimed at characterizing variation in this species’ life history in different parts of its range should be undertaken, as these differences might have an impact on future management efforts. For example, the two desert slope populations may differ substantially in several aspects of life history relative to the coastal slope populations. Additional research into the prevalence and potential impacts of Bd fungus on this species is also particularly important. Finally, molecular analyses of population size and connectivity might be particularly valuable in this taxon.