OREGON SPOTTED FROG

Rana pretiosa Baird and Girard 1853b

Oregon spotted frog, Lane County, Oregon. Courtesy of Troy Hibbitts.

Status Summary

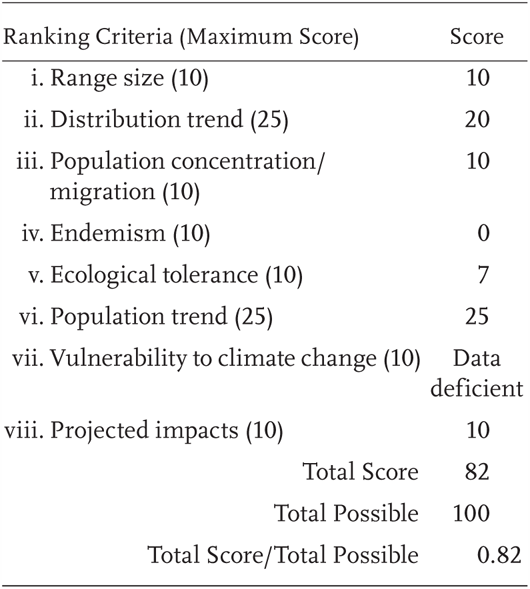

Rana pretiosa is a Priority 1 Species of Special Concern, receiving a Total Score/Total Possible of 0.82 (82/100). During the previous evaluation, it was also designated as a species of special concern (Jennings and Hayes 1994a) and it was listed as federally Threatened in 2014 (USFWS 2014). We are aware of only two unverified site records for this species in California in the last 25 years.

Oregon Spotted Frog: Risk Factors

Identification

Dorsally, Rana pretiosa is a dark-brown, reddish, or greenish frog with black spots or blotches (McAllister and Leonard 1997). The dorsal blotching is usually irregular around the edges, rather than sharply demarcated, and has a small light spot in the center of the larger spots. The venter is usually mottled and has a base color that changes from cream white at the chin to orange more ventrally (Dunlap 1955, Stebbins 2003). The ventral coloration often appears to be superficial or “painted on” (Dunlap 1955, Nussbaum et al. 1983). Like many California ranids, this species has a prominent light stripe below the eye (particularly so in juveniles) and thin dorsolateral ridges that dissolve into a series of raised dots two-thirds to three-quarters of the way down the back. The call consists of a series of faint clicks, repeated roughly seven times in rapid succession (Briggs 1987, Stebbins 2003, Elliott et al. 2009).

Within its California range, this species is most likely to be confused with the Cascades frog (R. cascadae). Although similar, R. cascadae spots tend to have sharply defined edges, no light centers, and appear to be on the surface of the skin, reminiscent of black ink being splattered on the frog (Stebbins 2003). In addition, the underside of the legs are yellow tan in R. cascadae (reddish in R. pretiosa), the eyes are oriented dorsally when viewed from above in R. presiosa (oriented outwardly in R. cascadae), and R. pretiosa has full, rather than partial webbing between the toes of the rear legs. The Columbia spotted frog (R. luteiventris) may also occur in California, and it could also be confused with R. pretiosa (see the “Distribution” section).

Taxonomic Relationships

Green et al. (1996, 1997) divided Rana pretiosa into two species, R. pretiosa and R. luteiventris, based on morphology and allozyme variation. The two taxa are morphologically similar (usually distinguishable in the field based on the ventral mottling in R. pretiosa; M. Hayes, pers. comm.), but preserved specimens can usually be differentiated with a series of head measurements (Green et al. 1997). The two species are also diagnosable using allozymes (Green et al. 1996) and mitochondrial DNA cytochrome-b sequence (Funk et al. 2008).

Life History

No data on life history of California populations exist and much of the data from elsewhere in the range occurred before the partitioning of Rana pretiosa and R. luteiventris. As California populations of R. pretiosa are at the extreme southern edge of the species’ range, the timing of life history events may occur earlier relative to those reported from more northerly sites, although the high elevation of California sites may compensate for any potential latitudinal gradient. California populations were geographically closest to Oregon frogs from the Klamath basin, and those populations may serve as the best models for California.

Frogs emerge from hibernation as soon as the winter thaw permits (Stebbins 2003) and water temperatures rise to about 6°C (C. Pearl, pers. comm.). Rana pretiosa breeds explosively soon after emergence, usually over a 1- or 2-week period. Males often congregate in shallow water and begin to call (Licht 1969, Nussbaum et al. 1983). Egg masses are deposited together in large groups in vegetated margins of large permanent aquatic habitats, usually at the high-water mark. The species can experience high egg mass mortality when waters recede rapidly, leading to stranding, desiccation, and/or freezing (Licht 1971, Briggs 1987). However, eggs from multiple sites in Oregon were found to resist near-freezing temperatures as long as they remained beneath the water surface (Bowerman and Pearl 2010). Artificially incubated egg masses hatch in as few as 72 hours to as many as 400 hours, depending on temperature (25°C and 10°C, respectively), followed by metamorphosis in approximately 4 months (Licht 1971).

Males appear to have lower survivorship than females, presumably due to the longer periods of time that they spend in breeding congregations and the resulting exposure to predation (Licht 1974, Chelgren et al. 2008). Post-metamorphic frogs consume a wide variety of invertebrate prey including insects, occasional mollusks, and crustaceans, as well as small vertebrates including anurans (Nussbaum et al. 1983, Licht 1986b, Pearl and Hayes 2002, Pearl et al. 2005b).

Habitat Requirements

Information on habitat utilization in California is very limited, although habitat requirements are better studied elsewhere in the range. The species appears to seasonally use different habitat types (Watson et al. 2003, Chelgren et al. 2008). Rana pretiosa is highly aquatic and rarely found away from the water (Licht 1986a). It frequently uses temporary pools, ditches, and other shallow water sources, but nearby deep permanent water is always required and serves as a refuge for adult frogs during dry parts of the year and during drought (McAllister and Leonard 1997, Watson et al. 2003). Breeding occurs in shallow water with aquatic vegetation (Licht 1971, Watson et al. 2003). In Oregon, oviposition sites occurred, on average, 14.1 m (range 0.08–35.0 m) from the shore in water that was 18.5 cm deep (range 1–57 cm) (Pearl et al. 2009). At one site in Washington, the species overwintered in shallow water, where it buried itself at the base of emergent plants (Watson et al. 2003). Overwintering in flowing springs has also been documented (Chelgren et al. 2008). Overland dispersal appears to be quite limited, and the species may require habitat where the shallow-water breeding and over-wintering habitats are connected to deep-water refuge habitat by intervening water during early spring and late fall to allow inter-habitat migrations (Watson et al. 2003).

The habitat requirements for R. pretiosa have likely contributed to its declines. The diversity of habitat types that are used, coupled with the requirement that they are connected by intervening stretches of water, is fairly specific and is probably only common in large, relatively intact wetland complexes. These complexes are becoming increasingly rare throughout the species’ range as landscapes are drained and converted to agriculture and grazing.

Data are limited on effects of grazing on this species. At one site in western Washington where reed canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea) forms dense stands, Watson et al. (2003) suggested that grazing could help open patches and make them suitable for R. pretiosa. However, grazing also has the potential to reduce water quality and cover from predators. Additional work is needed on how the timing and intensity of grazing affect frog behavior and habitat use.

Distribution (Past and Present)

Few localities for Rana pretiosa have been documented in California, and all known localities appear to be extirpated. Historically, R. pretiosa occurred in the northeastern corner of California, ranging south to Plumas and Tehama Counties and west to the eastern portions of Sikiyou, Shasta, and Tehama Counties (Slevin 1928). Within this range, the species has been found in scattered localities in Modoc, Shasta, and Siskiyou Counties (Stebbins 1972, Jennings and Hayes 1994a), with the last documented record occurring in a woodpile in Cedarville, Modoc County, in 1989 (Jennings and Hayes 1994a). This last record is somewhat anomalous, since the frog was found in a heavily modified area near the town center of Cedarville, in habitat that seems to be unsuitable for the frog. Given the very specific habitat requirements of R. pretiosa, the fact that no specimen from the site was ever examined by a herpetologist and no vouchers exist, it is possible that this is a misidentified or human-introduced specimen (L. Groff, pers. comm.; M. Hayes, pers. comm.). It remains possible that isolated populations still persist, particularly in remote portions of the Warner Mountains and on private land in Surprise Valley, Modoc County. Fairly recent surveys in the Warner Mountains, Modoc Plateau, and Pitt River drainage failed to locate any individuals (Jennings and Hayes 1994a, Groff 2011). There is an unverified sighting of a “spotted frog” in Surprise Valley from November 2008 (L. Gray, pers. comm.), but a follow-up survey at this locality revealed only Psuedacris regilla. A more recent survey comprising 18 localities selected using a species distribution model for this species did not detect R. pretiosa in California (Groff 2011), although the southernmost extant locality in Oregon is only about 10 km from the state border. Between 2012 and 2013, USFWS biologists conducted additional surveys at 12 sites within the Pit River watershed and Warner Mountains. Again, no evidence of R. pretiosa was found (USFWS-Klamath Falls Field Office, unpublished data, 2013).

Outside of California, R. pretiosa is patchily distributed from extreme southwestern British Columbia, south through Washington and Oregon (Green et al. 1997). This distribution is fragmented, and the species has undergone severe declines through most of its range (McAllister et al. 1993, Green et al. 1997). Declines are thought to have occurred disproportionately in lowland areas, and over two-thirds of the remaining populations occur along the crest and eastern slopes of the Cascade Range (Pearl et al. 2009).

It is possible that some R. pretiosa in California, particularly those east of the Warner Mountains in Modoc County, could actually be R. luteiventris. There are known R. luteiventris populations approximately 16 km north of the California border on the eastern slopes of the Warner Mountains, making the presence of R. luteiventris in California plausible (Funk et al. 2008; M. Hayes, pers. comm.). However, the species has not been documented in California.

Trends in Abundance

No abundance data for California populations exist. Reports from parts of the Willamette Valley, Oregon, and Puget Lowlands, Washington, suggest that Rana pretiosa was common in those areas around the 1930s. Declines are thought to have been occurring for a large part of the twentieth century (Dumas 1966, McAllister et al. 1993, Pearl and Hayes 2005). At one time, the species was apparently common in Warner Valley, Oregon, immediately north of Surprise Valley in California (Cope 1883). Any remaining populations in California are likely to be isolated and on private land that has not been surveyed. A recent species distribution model generated a set of potential sites, some of which were surveyed, but no California populations were found (Groff 2011).

Nature and Degree of Threat

At least four major factors have likely contributed to the decline of Rana pretiosa in California. First, the species has been strongly impacted by the loss of the extensive wetland complexes that were once common in northern California. As land has been drained and modified for livestock grazing and agriculture, the overall amount of available acreage that provides the precise suite of habitat types used by this species has declined. This loss of wetland habitat is further exacerbated by climate projections for northeastern California, which predict increasing temperatures, strongly decreasing precipitation, and reduced snowpack (PRBO 2011); all of these changes will reduce permanent wetlands and place increasing demands on the remaining aquatic habitat. Second, R. pretiosa appears to be sensitive to relatively low levels of nitrates and nitrites resulting from agricultural runoff (i.e., those meeting EPA allowances for drinking water; Marco et al. 1999). This observation is consistent with the precipitous declines observed in lowland Oregon and Washington populations, which have been more heavily impacted by agriculture than higher-elevation populations. Application of the pesticide DDT was also correlated with die-offs in the closely related R. luteiventris in northern Oregon (reported as R. pretiosa; Kirk 1988). Third, the species appears to be sensitive to introduced exotic predators, particularly bullfrogs and exotic fishes. Some data indicate that it is likely more sensitive to the presence of bullfrogs than other native ranid frogs. In areas where R. aurora and R. pretiosa are sympatric, stronger declines were observed in R. pretiosa than R. aurora in areas where bullfrogs have invaded (Pearl et al. 2004). Laboratory experiments also demonstrate a differential impact of bullfrogs on R. pretiosa relative to R. aurora, likely due to R. pretiosa’s more strongly aquatic life history (Pearl et al. 2004). Bullfrogs have also been hypothesized to negatively impact small R. pretiosa populations via reproductive interference (Pearl et al. 2005c). In combination with the well-documented effects of nonnative fishes on western ranid frogs (Adams 1999, Lawler et al. 1999, Adams 2000, Joseph et al. 2011), this suite of nonnative predators is likely to have a strong negative effect on R. pretiosa populations. Finally, Bd has been found to be present in remaining populations of R. pretiosa (Pearl et al. 2007, Hayes et al. 2009), although experimental work suggests that the species may be resistant (Padgett-Flohr and Hayes 2011). However, given the importance of Bd in some anuran declines, further work on its impact on R. pretiosa is warranted.

Given the rarity of R. pretiosa records from California and our lack of historical population parameters, it is impossible to differentiate between these causes. However, it is reasonable to assume that several or all of these factors were involved in the decline of the species in California.

Status Determination

The limited California range of Rana pretiosa and its apparent extirpation from the few known historic localities are the main drivers for its high score. The paucity of historical records in California suggests that this taxon may have historically been rare in the state, and its specialized ecological requirements (large permanent wetlands, specialized sub-habitats for breeding, hibernation, and growth) make it inherently sensitive to declines. Together, these factors justify a Priority 1 designation for this species.

Management Recommendations

Ongoing management efforts for this species should be coordinated through the range-wide conservation strategy that the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is leading and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife is participating in (B. Bolster, pers. comm.). Cushman and Pearl (2007) recently assessed Rana pretiosa conservation needs and provided a detailed roadmap for management of this species. Our recommendations largely follow theirs. If the surveys outlined below identify any remaining populations of this species in the state, the wetland habitat supporting the population should be protected from fragmentation and modification, including the introduction of exotic fishes and amphibians. Captive populations of this species should also be established to serve as assurance colonies, should the last wild populations go extinct. If continued surveys suggest that the species is extirpated from California, captive breeding and reintroduction programs could be initiated with Oregon animals if appropriate habitat can be identified and protected. Given the very high levels of genetic differentiation and population structure found among extant Oregon and Washington populations (Blouin et al. 2010), populations from the southern Klamath Basin genetic unit are probably the best candidates for such a reintroduction in California. Beyond these two steps, effective management of this taxon in California will require additional research into the causes of decline.

Monitoring, Research, and Survey Needs

Comprehensive surveys throughout Rana pretiosa’s known historic range should be conducted to determine if any populations persist in the state. Surveys of remaining large wetland complexes are particularly important, as are surveys of potential habitat on private property. A recent species distribution model (Groff 2011) identified and surveyed some, but not all, of the predicted localities that may support this species in California, and this study provides an excellent starting point for additional surveys. Significant habitat that has not yet been surveyed remains on private property, particularly east of the Warner Mountains (although R. luteiventris may replace R. pretiosa in this area). The aforementioned recent surveys made a particular effort to gain access to private land, but permission was only granted in approximately 15% of cases (Groff 2011). Future surveys should continue to build partnerships with private stakeholders and survey large wetland complexes on private lands. If any populations are found, nonlethal tissue samples should be collected so that species identification can be verified with molecular data.

Should any populations be located, a monitoring program in conjunction with life history research should immediately be initiated with the goal of quantifying population sizes and connectivity (if multiple adjacent populations are found) and to allow for a better understanding of habitat requirements and causes of decline in this species. Molecular genetic studies using microsatellite and/or single nucleotide polymorphism data from multiple nuclear markers can provide valuable insights into historical population declines/expansions and should be conducted if any native populations are discovered. In addition, given the very high levels of population structure found among extant Oregon and Washington populations, any California populations should be surveyed for genetic variation and integrated into the existing species-wide genetic dataset (Blouin et al. 2010).