FLAT-TAILED HORNED LIZARD

Phrynosoma mcallii (Hallowell 1852)

Flat-tailed horned lizard, Sonora, Mexico. Courtesy of Rob Lovich.

Status Summary

Phrynosoma mcallii is a Priority 2 Species of Special Concern, receiving a Total Score/Total Possible of 57% (63/110). During the previous evaluation, it was also considered a Species of Special Concern (Jennings and Hayes 1994a).

Flat-Tailed Horned Lizard: Risk Factors

Identification

Like other horned lizards, Phrynosoma mcallii has a round body and is dorsoventrally flattened. It is readily distinguished from other horned lizards by a dark middorsal stripe (Smith 1946). The two largest horns behind the head are long and thin, the tail is broad and flat, and two rows of lateral spines run down each side of the body. The limbs are long and thin relative to other horned lizards. The dorsum is cryptically colored, ranging from pale cream to a light rusty brown, and the ventral surface is white and unmarked. Adults can be as large as 8.7 cm SVL (Boundy and Balgooyen 1988, McGrann et al. 2006), but 6.5–8.0 cm SVL is more typical.

Phrynosoma mcallii co-occurs in narrow sympatry with the desert horned lizard (P. platyrhinos) along the Salton Trough in California (Stebbins 2003). The two species are easily distinguished because P. platyrhinos has a single row of lateral spines, shorter horns on the head, and lacks a dark middorsal stripe (Smith 1946, Stebbins 2003). Morphologically intermediate animals thought to be hybrids have been observed near Ocotillo, California (Stebbins 2003), and near Yuma, Arizona (Young 2010).

Taxonomic Relationships

Mulcahy et al. (2006) conducted a phylogeographic study of Phrynosoma mcallii and P. platyrhinos. They identified management units for P. mcallii on either side of the Colorado River. Populations west of the Imperial Valley were historically connected but are now fragmented by human development. The Coachella Valley population, in particular, appears to be highly isolated (Mulcahy et al. 2006).

Life History

Phrynosoma mcallii is generally most active in the summer and inactive during the winter, although there is some flexibility in their winter dormancy behavior. Adult activity in the Coachella Valley in Riverside County peaked from June to August, with little or no activity observed from November to February (Barrows and Allen 2009). At sites in San Diego and Imperial Counties, adults entered hibernation burrows from early October to late December, and smaller animals entered dormancy later than larger animals (Grant and Doherty 2006). The average onset of winter dormancy occurred in mid-November in Imperial County and lasted for an average of 89 days (range 14–138 days), with most animals emerging in mid-February (Muth and Fisher 1992). Radiotelemetry studies have shown that not all individuals enter this distinct period of dormancy (Muth and Fisher 1992, Wone and Beauchamp 2003, Grant and Doherty 2006). Juveniles have been observed surface-active on warm days in December, suggesting that winter dormancy behavior may be more flexible in juveniles compared to adults (Grant and Doherty 2006). Burrows at sites in Imperial and San Diego Counties were 6 cm deep on average (range 2–17; Muth and Fisher 1992, Grant and Doherty 2006). Summer burrows in Yuma, Arizona, were 25–30 cm deep and 70–80 cm long (Young and Young 2000).

Daily activity patterns shift seasonally (Mayhew 1968, Wone and Beauchamp 2003). At Ocotillo Wells State Vehicular Recreation Area (Imperial and San Diego Counties), P. mcallii was active throughout the day in spring and fall but showed a bimodal daily activity pattern in the summer (Wone and Beauchamp 2003). Phrynosoma mcallii was out in the open during the early morning but retreated under shrub cover by 10:00 a.m. (Wone and Beauchamp 2003). When substrate temperatures exceeded 49°C, lizards entered burrows and reemerged in the evening when substrate temperatures dropped below 47°C (Wone and Beauchamp 2003). Norris (1949) also reported animals retreating between 10:00 and 11:00 a.m. in Riverside County during July. In outdoor enclosures, Heath (1965) observed shade-seeking behavior when body temperatures averaged 40°C and emergence from shade when mean body temperatures were 34.9°C. Brattstrom (1965) recorded lizards at temperatures ranging from 29.3°C to 41.0°C.

Breeding activity has been observed in the field from early May through the end of August (Setser 2004, Barrows and Allen 2009, Young 2010). Adults emerge from winter dormancy in reproductive condition, with testes at maximum size in males and enlarged yolked follicles present in females (Howard 1974). Eggs are laid in burrows dug by the lizards (Setser 2004) and can be deposited from 14 to 90 cm deep, depending on soil moisture (Setser 2004, Young 2010). Clutch sizes range from 2 to 10 eggs, with the average typically around 5 (Norris 1949, Stebbins 1954, Howard 1974, Pianka and Parker 1975, Setser 2004, Young 2010).

Under good conditions, P. mcallii can breed early in the season, young can attain adult size rapidly and breed in their first year, and two clutches per season are possible (Howard 1974, Turner and Medica 1982, Muth and Fisher 1992, Barrows and Allen 2009, Young 2010). In multiple-clutch years, the first cohort emerges in late July or early August at 35–37 mm SVL (Howard 1974, Turner and Medica 1982, Muth and Fisher 1992). These hatchlings may be capable of reproducing in their first spring because they can reach near adult sizes before entering winter dormancy (Howard 1974, Muth and Fisher 1992). The second cohort emerges in late August or early September (Howard 1974, Turner and Medica 1982). However, these animals are only ∼38 mm SVL in October and may not reach sexual maturity until another season of growth has occurred (Howard 1974, Muth and Fisher 1992). Working in Yuma, Arizona, Young (2010) observed that hatchlings and yearlings did not attain adult size by the following summer under drought conditions, but in wet years animals attained adult size within six months.

Males usually have larger home ranges than females, and home ranges tend to be larger in wet compared to dry years (Wone and Beauchamp 2003, Setser 2004, Young 2010). Radio-telemetry studies at the Ocotillo Wells State Vehicular Recreation Area found average male home range sizes of 1.8–2.4 ha and female home ranges of 0.9–1.3 ha (Wone and Beauchamp 2003, Setser 2004). Setser (2004) observed high site fidelity, with few lizards shifting their range centers outside of the home range used in the previous year. Near Yuma, Arizona, average male home range size varied from 2.5 ha (males) and 1.3 ha (females) in a very dry year to 10.5 ha (males) and 1.9 ha (females) in a very wet year (Young and Young 2000). In wet years at the Yuma, Arizona, site, maximum mean daily movements were 200–700 m, compared to only 50–100 m in drier years (Young 2010).

Survivorship has been measured in a few populations using radiotelemetry and mark–recapture methods. At Ocotillo Wells State Vehicular Recreation Area, adult yearly survivorship was estimated as approximately 50% over a 2-year study period (Setser 2004). This high survivorship rate was attributed to the scarcity of ground squirrel predators, with only 5–8% of radio-tagged lizards lost to predation (Setser 2004). Similarly, adult survivorship over 2 years in Imperial County was approximately 50%, with half of known mortalities due to ground squirrel predation (Muth and Fisher 1992). In contrast, 39% (21/54) of radio-tagged P. mcallii succumbed to predation at the Yuma, Arizona, site in 1 year, with most deaths attributable to ground squirrels (Young 2010). Predation rates were only 10% in another year at this site (Young 2010). Survivorship of hatchlings over their first year was greater than 50% across multiple cohorts in Coachella Valley (Barrows and Allen 2009). Survivorship declined in subsequent years to less than 20% for 2-year-olds and less than 5% for 3-year-olds (Barrows and Allen 2009). Such low survivorship beyond the first year suggests that early maturity and multiple clutches may be key to positive growth of populations in the Coachella Valley (Barrows and Allen 2009).

Phrynosoma mcallii is a dietary specialist on ants, particularly native harvester ant species. Ants typically make up over 90% of prey items in stomach content and scat analyses (Pianka and Parker 1975, Turner and Medica 1982, Young 2010). In 106 specimens examined by Pianka and Parker (1975), 97% of prey items were ants. While at least 11 species of ants have been identified from scats, ants from the genera Pogonomyrmex and Messor are most commonly taken (Turner and Medica 1982). Near Yuma, Arizona, ants (mostly genus Pogonomyrmex) constituted 99% of prey items, with a few beetles taken as well (Young 2010).

Habitat Requirements

In California, Phrynosoma mcallii occurs in several Sonoran Desert habitat types, including sandy areas (flats, hills, and valleys), salt flats, badlands, and gravelly areas (Stebbins 2003, Turner and Medica 1982). While they may prefer areas with a layer of fine, wind-blown sand, P. mcallii also occur on substrates ranging from hard-packed soils to sand dunes and mud hills (e.g., Beauchamp et al. 1998, Muth and Fisher 1992). For example, at Ocotillo Wells State Vehicular Recreation Area, a site where sandy habitats are highly disturbed by off-highway vehicle use, P. mcallii abundance was highest in sparsely vegetated gravel and mud hills in less-disturbed areas (Beauchamp et al. 1998).

In the Coachella Valley, P. mcallii were 2–6 times more abundant on stabilized sand fields than on active dunes (Barrows and Allen 2009) and were not observed in ephemeral sand fields or stable dune habitats (Barrows and Allen 2010). A reduction in windblown sand over the last few decades due to climatic factors and disturbance is thought to be responsible for the apparent absence of P. mcallii from ephemeral sand fields, habitats that still support P. platyrhinos populations (Barrows and Allen 2010). Lizards selected moderately compacted sands in both stabilized sand fields and active dunes, and this habitat feature may be important for maintaining the integrity of burrows while still being loose enough for digging (Barrows and Allen 2009).

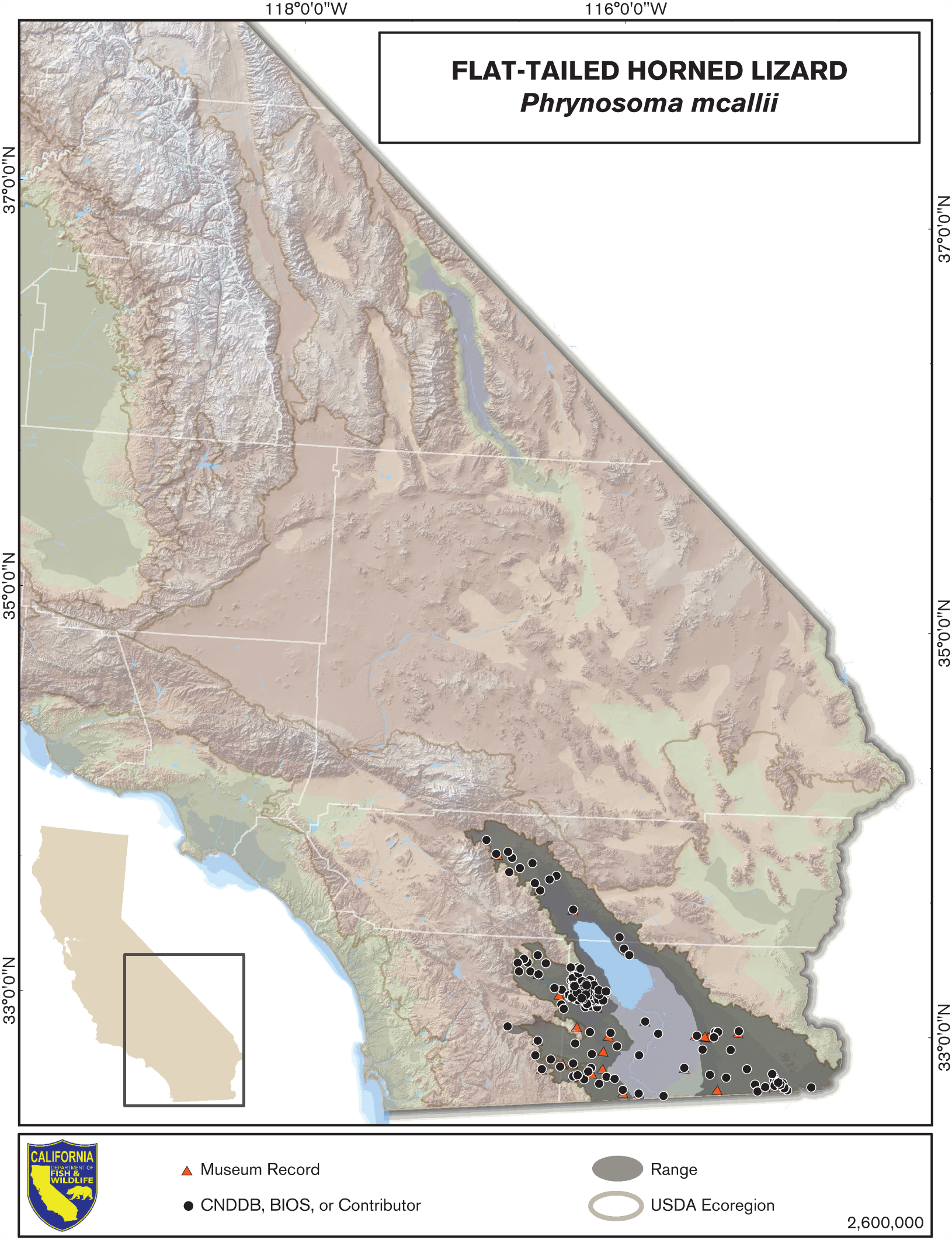

Distribution (Past and Present)

Phrynosoma mcallii is a desert animal with the smallest range of any Phrynosoma species that occurs in the United States (Stebbins 2003). It is found from the Coachella Valley in Riverside County south into extreme northeast Baja California and northwest Sonora, Mexico, and east to the extreme southwest corner of Arizona (Stebbins 2003). The species typically occurs below 230 m elevation, but has been found as high as 520 m (FTHL ICC 2003, Rorabaugh and Young 2009, Turner et al. 1980). The currently occupied range is patchily distributed within the historical range. In California, these areas are the Coachella Valley, west of the Salton Sea and the Imperial Valley, and east of the Salton Sea and the Imperial Valley on the west side of the Colorado River (Mulcahy et al. 2006).

The Flat-tailed Horned Lizard Interagency Coordinating Committee estimated that nearly half of the entire range of P. mcallii has been altered by human activities, with 39–43% of the historical habitat in the United States converted to agriculture, urban areas, or other uses (reviewed in FTHL ICC 2003). The historical range of P. mcallii in California has been estimated at 700,000–900,000 ha, mostly in Imperial County but including parts of eastern San Diego and central Riverside Counties (reviewed in FTHL ICC 2003). Of this historical range, the Flat-tailed Horned Lizard Interagency Coordinating Committee further estimated that 400,000 ha of habitat remain in California (FTHL ICC 2003).

Within the Coachella Valley, Barrows et al. (2008) used niche models to estimate that 83–92% of historically occupied habitat has been lost to development, agriculture, fragmentation, or disruption of windblown sand transport processes. Of the estimated 33,500 ha of historically available suitable habitat, 2600 ha of potential habitat remain in the valley, of which only 1400 ha is currently occupied (Barrows et al. 2008).

Trends in Abundance

Phrynosoma mcallii has long been regarded as a relatively rare species (e.g., Klauber 1939). Density is very difficult to estimate for this cryptic species, and earlier estimates were based on scat counting methods that are no longer thought to be reliable (see the “Monitoring, Research, and Survey Needs” section). Despite these difficulties, dramatic declines have been documented in some areas (Turner and Medica 1982).

Populations of P. mcallii appear to naturally fluctuate in abundance, and the drivers of these dynamics are beginning to be explored. In the Coachella Valley, the population declined by about 50% per year during 2002–2005, resulting in an overall decline of 90% (Barrows and Allen 2009). However, in the following 2 years, P. mcallii abundance rebounded to half of the 2002 levels (Barrows and Allen 2009). Unlike some other desert species, abundance was not correlated with year-to-year variation in rainfall (Barrows and Allen 2010). Instead, increased rainfall was negatively correlated with the abundance of ant prey and positively associated with increased soil compaction (Barrows and Allen 2009). Other studies have also found associations between P. mcallii abundance and ant abundance (e.g., Turner and Medica 1982, Rorabaugh et al. 1987).

Mark–recapture studies have generated minimum density estimates of approximately 1.1/ha at Ocotillo Wells State Vehicular Recreation Area (Setser 2004) to 6.1/ha in Imperial County (Turner and Medica 1982). Increasingly sophisticated statistical methods for estimating abundance have been employed to compensate for the low abundance and cryptic nature of P. mcallii. Grant and Doherty (2007) working in Imperial County estimated densities from 0.41 to 1.55 lizards/ha at different sites, using methods that explicitly account for detection probability (see the “Monitoring, Research, and Survey Needs” section).

Nature and Degree of Threat

Habitat loss and fragmentation due to urban development and agriculture have been the major threats faced by Phrynosoma mcallii populations in California, with future threats anticipated due to renewable energy development. Phrynosoma mcallii are particularly sensitive to such disturbances because they are ecological specialists, and their ability to recover from population declines through reproductive responses is highly dependent upon favorable environmental conditions.

Phrynosoma mcallii is negatively impacted by fragmentation, and edge effects can extend several hundred meters into undisturbed habitat (Young and Young 2005, Barrows et al. 2006). Based on surveys of lizard tracks, Barrows et al. (2006) found that P. mcalllii in the Thousand Palms Oasis Preserve in Coachella Valley, Riverside County, experienced negative edge effects along the desert/suburban boundary of the preserve. Phrynosoma mcallii were at low abundance within 150 m of the edge compared to farther into the preserve. The mechanism behind the negative effect was hypothesized to be mortality due to roads and subsidized predators such as shrikes and kestrels. Bird predators were positively associated with suburban edge habitats because of increased availability of trees and poles for perching compared to desert habitat. There was no edge effect on native harvester ant abundance and nonnative ants were not detected, so the edge effect is probably not due to impacts on prey availability (Barrows et al. 2006). In another study in Yuma, Arizona, 90% of shrike-killed P. mcallii were within 10 m of a road (Young 2010). Nonnative ants and plants may also pose a threat to P. mcallii (see the “Monitoring, Research, and Survey Needs” section). Wind and solar development may be of particular concern in western Imperial County and east of the Imperial Sand Dunes, while geothermal development may threaten populations inside of the Ocotillo Wells State Vehicular Recreation Area (J. Weigand, pers. comm.). Such development may lead to habitat degradation and loss, as well as increased fragmentation.

Off-highway vehicle use has long been suspected of negatively impacting P. mcallii populations through direct effects such as mortality and indirect effects on habitat quality. Within protected Management Areas (see the “Management Recommendations” section), off-highway vehicle use is restricted to designated areas (Grant and Doherty 2009). Outside of these protected areas, approximately 100,000 ha of remaining habitat may be subject to off-highway vehicle activity, an area encompassing more than a quarter of remaining habitat in California (Grant and Doherty 2009). Grant and Doherty (2009) experimentally tested the hypothesis that off-highway vehicles crush dormant P. mcallii by controlled rides over radio-tagged animals in burrows. None of the animals in their study died or were injured, suggesting that direct effects on animals in burrows may be weak. Direct mortality of surface-active P. mcallii due to off-highway vehicle activity has been reported anecdotally from some sites (e.g., Turner and Medica 1982, Muth and Fisher 1992). McGrann et al. (2006) found that lizard body mass, but not density, was higher on sites with low off-highway vehicle impact compared to high-impact areas. The density of ant mounds (i.e., prey) was also higher in low-impact sites, supporting the possibility of indirect effects of off-highway vehicle use on P. mcallii (McGrann et al. 2006).

Aside from increases in temperature, there is little consensus as to how climate change will affect the Sonoran Desert region of California where P. mcallii occurs. Mean annual temperatures are expected to increase, with 22 additional extremely hot days per year (where temperatures exceed the long-term 95th percentile) and 10 fewer days below 0°C predicted (Bell et al. 2004). High temperatures may limit surface activity, whereas warmer, shorter winters may increase opportunities for growth and reproduction. Estimates of changes in rainfall range from modest increases in mean annual rainfall up to 45% decreases (reviewed in PRBO 2011). This uncertainty in how precipitation will change makes it difficult to predict how P. mcallii will be affected. The effect of rainfall timing and magnitude on P. mcallii populations is likely complex, as drought reduces juvenile growth rate and adult movement, but wet years reduce prey abundance (see the “Life History” section). How fire dynamics will change in this area is also highly uncertain (Westerling and Bryant 2008). Little change is expected in vegetation communities (Lenihan et al. 2008, Stralberg et al. 2009).

Status Determination

The specialized diet of Phrynosoma mcallii, its low reproductive rates, and small geographic range in a highly fragmented region of California contribute to a Priority 2 Species of Special Concern status.

At the federal level, efforts to secure range-wide protection for P. mcallii have been underway for several years, with the species first identified as a candidate for listing under the federal Endangered Species Act in 1982 (reviewed in USFWS 2011a). In 1989, this lizard was rejected for listing under the California Endangered Species Act. Following these efforts, several state and federal agencies comprising the Flat-tailed Horned Lizard Interagency Coordinating Committee signed a voluntary conservation agreement, which resulted in the protection of management and research areas and a plan for monitoring the species (Foreman 1997). In 2003, the range-wide management strategy was updated, providing reviews of biology, threats, and management recommendations for P. mcallii (FTHL ICC 2003). In 2011, P. mcallii was again denied federal protection under the Endangered Species Act (USFWS 2011a). In broad terms, the USFWS concluded that the threats to P. mcallii that initiated consideration for listing have been largely addressed by management efforts (USFWS 2011a). However, P. mcallii populations continue to face a variety of threats throughout their range in California.

Management Recommendations

The main management actions that can support Phrynosoma mcallii populations are those that limit habitat disturbance and destruction. Development that leads to habitat conversion or fragmentation should be avoided or limited in P. mcallii habitat. Renewable energy projects should consider potential negative impacts on P. mcallii. Limiting off-highway vehicle use to the overwintering season when animals are less likely to be surface-active may help limit direct mortality impacts. Roadside barriers and crossing structures should be investigated to reduce road mortality in areas where roads may be barriers to population connectivity. The use of pesticides in or near P. mcallii habitat should consider potential negative impacts on native ant prey that are an important determinant of habitat quality for this species. Habitat corridors should be established or maintained to promote connectivity among remaining populations, particularly across the United States–Mexico border. Assisted migration may be important for ensuring gene flow across obstacles such as fences along the United States–Mexico border. Restoration of degraded habitats could include activities such as manipulating soil properties, removing or controlling nonnative plants, and replanting of native plant species that provide food for harvester ants and open habitat for P. mcallii.

The Flat-tailed Horned Lizard Interagency Coordinating Committee has implemented a management strategy for P. mcallii (FTHL ICC 2003). In California, this strategy includes the establishment of three Management Areas and one Research Area encompassing roughly 170,000 ha in regions of California deemed especially important to the species including the Borrego Badlands, West Mesa, East Mesa, and Ocotillo Wells. The conservation and management of these areas is described in the FHTL ICC (2003) document, and we refer the reader there for additional details. There is currently no management area in the northwestern portion of the range. However, the Coachella Valley Multiple Species Habitat Conservation Plan and Natural Communities Conservation Plan will protect approximately 44% of remaining habitat in Coachella Valley (FTHL ICC 2003).

Monitoring, Research, and Survey Needs

Monitoring Phrynosoma mcallii is difficult because this species is cryptic, population abundance fluctuates, and densities are often low. This results in low detection probabilities overall and a high degree of variation in detection probability with respect to different observers, habitats, substrates, and seasons. Phrynosoma mcallii is cryptically colored and also exhibits cryptic behavior, tending to freeze and/or bury itself in the sand instead of fleeing (Bryant 1911). Young (2010) observed that radio-tagged individuals in Arizona were almost always motionless when approached, but tracks showed that the animals ran 1–2 m to reach the cover of twigs or vegetation, then froze to avoid detection. Over 25% of the time, fleeing individuals also shuffled into the sand (Young 2010). Such crypsis results in a strong effect of observer experience on survey success (Grant and Doherty 2007).

To deal with these challenges, researchers have tried to use statistical methods to explicitly incorporate detection probability (the probability of seeing lizards if they are present) into mark–recapture estimates of population abundance (e.g., Grant and Doherty 2007, Royle and Young 2008). Detection probabilities ranged from 0.06 to 0.15 (Young 2010) to as high as 0.52 on sandy plots intensively searched by experienced observers (Young and Royle 2005). Range-wide monitoring by members of the FTHL ICC from 2005 to 2012 yielded detection probabilities ranging from 0.15 in the Borrego Badlands to 0.79 in the Yuma Desert (R. Lovich, pers. comm.), and these monitoring efforts are ongoing. Even with increasingly sophisticated mark–recapture analyses, data collection requires substantial effort, and abundance estimates will always be plagued by low detection probabilities. Because of these challenges, distinguishing population declines from natural fluctuations in abundance is difficult, unless declines are severe. As an alternative, Young (2010) recommended monitoring presence/absence over large areas using scat surveys.

Scat counts were commonly used into the 1990s to estimate abundance, but their reliability for measuring density has subsequently been questioned (e.g., Muth and Fisher 1992, Beauchamp et al. 1998). However, scats have been shown to be a good indicator of P. mcallii presence, at least in areas where congeners are absent (Young and Royle 2005). If scats are present on a 0.75 ha plot, there is a >99% probability of an observer detecting them within an hour (Young and Royle 2005). Young (2010) proposed that such scat surveys could be useful for delineating occupied habitat across large areas and that monitoring changes in site occupancy over time might be a more viable monitoring strategy than trying to estimate abundance.

In addition to improved monitoring strategies, other research needs include determining the effects of introduced species, the design and efficacy of road-crossing structures, and landscape genetic studies of population connectivity. An additional important research problem is to identify and monitor processes that reduce the abundance of ant prey and/or affect sand compaction (Barrows and Allen 2009). Monitoring for the spread of Argentine ants, which have been shown to negatively impact P. blainvillii, may also be warranted, especially along suburban–desert boundaries. Argentine ants have invaded the Coachella Valley but to date are not known to have moved into P. mcallii habitat (Barrows et al. 2006). Fire ants may also pose a threat to P. mcallii (J. Weigand, pers. comm.), and their spread and potential impacts should be studied. Nonnative plant species are suspected to negatively impact horned lizards by reducing the availability of open habitat and seed-producing plants and by impacting locomotion (Germano et al. 2001, Newbold 2005, Barrows et al. 2009, Rieder et al. 2010). Introduced plants such as tall-growing or Sahara mustard (Brassica tournefortii) now occur in P. mcallii habitat, and the effects of these species require further study (J. Shedd, pers. comm., Barrows 2012). Barrier fences that prevent lizard access to roads have been successful in Yuma, Arizona (e.g., Gardner et al. 2004), and may be beneficial in targeted areas in California. However, more research is needed into crossing structure design and siting to prevent further fragmentation of populations. Finally, a clearer understanding of the extent of habitat fragmentation (using both genetic and mark–recapture methods) and how it affects population viability is an important research need.