CHAPTER 1

Bold Claims to Cure a Raving King Let Loose a Cry for Data, 1789-1816

It would be a most fortunate circumstance for medicine and mankind . . . were the parliament to examine physicians on every disease, as they have lately done on the unfortunate malady of a Great Personage. The utility of the arithmetical system would then be as universally conspicuous throughout every disease, in any great emergency, as it was in insanity, or as it is in politicks and commerce.

—William Black (1789)

The King Is Mad; Long Live Statistics

The collection and manipulation of data, so central to the study of human heredity, knows no unique point of origin. The assembly of a committee of the House of Commons in January 1789 to inquire into George III’s apparent madness, potentially a crisis situation, brought to the fore some vital questions about proper recordkeeping. A highly politicized disagreement about the king’s medical prognosis had roused a furor among the royal physicians extending to Parliament and the nation. How could they anticipate whether he would recover in time to preclude any need for a regency? What confidence was to be placed in the Reverend Dr. Francis Willis, who had been brought in from the provinces to care for the king? The committee questioned Dr. Richard Warren, one of the king’s physicians:

Whether if Nine Persons out of Ten, placed under the Care of a Person who had made this Branch of Medicine his particular Study, had recovered, if they were placed under his Care within Three Months after they had begun to be afflicted with the Disorder, Doctor Warren would not deem such Person, either very skilful or very successful?

Warren answered yes, if so many really did recover.

Whether, in order to induce Doctor Warren to believe, that, for Twenty-seven years, Nine persons out of Ten had been cured, he would not require some other Evidence than the Assertions of the Man pretending to have performed such Cures?

I certainly should.1

Willis, having made very specific claims, could not back them up with written records. Dr. Warren’s sharp skepticism points to an emerging ethic of data and accountability as a basis for public knowledge. The administration of madness participated fully in an explosion of statistical activity across a range of scientific, bureaucratic, and professional projects that already was beginning to take shape. Public numbers were not only for legislators but also for common people, who were urged to calculate in order to judge their rulers as well as to better their lives. The debates sparked by Thomas Malthus’s Essay on Population in 1798 were unprecedentedly lively, if far from new. Medicine, too, experienced sharp controversies, most famously regarding the advantages of inoculation campaigns against smallpox. Many physicians, however, were not eager to be judged by their numbers. If patients and diseases were unique, undiscerning data could not reliably guide a treatment decision. A public campaign for “numerical method” took off finally in the 1820s, launching an era of statistical hope coupled with doubts about the old remedies.2 The treatment of the insane was more profoundly reshaped by numbers than was ordinary medicine. Asylum medicine, as an area of public health, had only a weak ethic of individualism. In an age when physicians were paid directly by patients they visited in their homes, hospitals were more like poorhouses. Much confinement of the mad was for the sake of public safety, and many patients, lacking the means to pay the costs of their treatment, were designated paupers. As public or charitable institutions, asylums were particularly vulnerable to accountability standards, which meant providing numbers for patient admissions and outcomes as well as for revenues and expenditures.3

Asylum statistics originated as a form of bookkeeping. The prototype of the patient reckoning was a balance sheet. John Strype’s 1720 edition of Stow’s classic survey of London includes tables for Bethlem Hospital (Bedlam) beginning in 1704. The “Disturbed Men and Women then brought in” for the year numbered 64, while 50 were “Cured of their Lunacy and Discharged,” and 20 more were “Buried,” leaving 130 patients under care. The table for 1705 shows 72 admissions, 34 cures, 29 deaths, and 137 patients remaining. (This arithmetic leaves 2 patients unaccounted for.) The next year, “as it was Published,” is “1705 to 1706,” with 72 patients admitted, 52 cured, and 13 buried. Strype gave another table extending from Easter 1706 to Easter 1707, followed by three years with no information, a table for 1711, five more unrecorded years, and tables for 1717 and 1718.4

If the accounting seems fragmentary, the therapeutic evidence was still more so. The reports from 1680 to 1705 claimed cure rates between 57% and 82%. Yet the patients discharged as cured were not distinguished in the records from those sent away still mad. Some, certainly, did not recover, for Bedlam had an announced policy to limit the residence of patients to about a year. (The evidence of the numbers, with annual admissions about half as numerous as patients remaining under care, implies an average stay of about two years.) Strype did not explain the calculation of cure rates, merely proclaiming: “So that by God’s Blessing for Twenty Years past, ending 1703, there have been above two Patients in three cured, as the Physician hath told me.” Yet Bethlem was in some manner held responsible for patient outcomes, and the higher powers were not so lax as to leave the numbers to happenstance. Hence the need for techniques of deception. A Bethlem historian remarks that they maintained a low death rate by proactively discharging weak or debilitated patients.5

Although many asylum officials continued to treat their records as proprietary into the nineteenth century, others were working to expand public access to data on the mad. Dr. William Black, who was trained up in medical arithmetic by the campaign for smallpox inoculation, had complained in 1781 that at Bethlem, the “relieved, cured and discharged, are jumbled into one list” so that none but its “eminent physician,” Dr. John Monro, could resolve what proportion is cured. Was this a backhanded compliment? In 1788, Black described the Bethlem medical books as an “untrodden wilderness.” The eminent Dr. Monro, however, introduced him to his estimable son, Thomas, who in turn led Black to yet another praiseworthy individual, the resident apothecary, John Gozna, “whose learning and curiosity induced him to keep a private register of all the patients, upon which, as incontrovertible data, I have founded and collected all the following tables and propositions.”6

At this point, the king’s madness turned the barren wilderness of Bethlem records into terrain of extraordinary value. Black, quite unexpectedly, found himself holding the key to unlock a great medical-political mystery. He set to work in great haste on a new edition of his just-published work on human mortality, withdrawing the 1788 version from circulation. In the crucial year of George III’s madness, he offered a solution to the urgent problem of prognostication. In a dedication of his book to the younger George, Prince of Wales, who was more than willing to assume the regency that Black’s numbers were likely to advance, Black declared: “I trust it will not be arrogant in me to say, there will be found considerable original, useful, and authentick information.” Such was the power of the medical numbers he prepared from Gozna’s record book. “I may with safety assert, that mine are the only numerical and certain data that ever have been published in any age or country, by which to calculate the probabilities of recovery, of death, and of relapse in every species and stage of insanity, and in every age.” The tools of arithmetic, so valuable “in politicks and commerce,” would now prove themselves in medicine. Insanity, long written off as “the most difficult and conjectural” topic in all of medicine, would at last yield to “medical arithmetick.”7

These were heady times for Black. “And it is not a little flattering, that the interrogatories, in this national dilemma, to some of the medical superintendants of Bedlam, were answered by a reference to my calculations.” His was the method of “authentick information,” the same method by which he had shown how to eliminate a million deaths annually in Europe. Arithmetic was the best medicine.8

In the wake of these investigations, the officers at Bethlem began to perceive recordkeeping as a political necessity and as a basis for medical legitimacy in the face of unsubstantiated claims by provincial practitioners. Black, who had spoken of his own data as certain and incontrovertible, put no faith in theirs. While Gozna’s private numbers, collected with the assistance of the Doctors Monro, were exemplary, the official ones had taken great liberties. Instead of accepting responsibility for patients sent away uncured, the authorities claimed to be making room for others with better prospects and, on this pretext, omitted them from the outcome statistics. Black continued: “Of those who are said to be annually cured, it is difficult to say in how many this may be only a lucid interval of reason: a transitory calm of this mental insurrection.”9

Philosophical writers have liked to suppose that death, being unequivocally real, supplies a basis of unquestioned fact. Black, who knew better, was scathing on manipulations of mortality figures. In his revised text of 1789, he condemned Bethlem’s reliance on “the ambiguous term discharged” for hundreds of patients “reported as sick and weak, as afflicted with epileptick fits, or with paralytick strokes, and none of them liberated from insanity when discharged.” They were entered as incurable, but some could just as well have been “added to the dead list.” The hospital sent them away early to evade responsibility for their impending deaths. The statistics, then, were formally correct but misleading. “This is truth, but not the whole truth.” These manipulations of Bethlem data tended to raise false hopes of recovery. And Willis was no more credible.10

John Haslam, Gozna’s successor as Bethlem apothecary, was still more severe. The king did in fact get better for a time, which seemed to lend credence to Willis’s bold claims. His supposed cures, indeed, far surpassed the experience at Bethlem, where, according to Haslam’s tables, almost two-thirds of the patients were sent away uncured between 1784 and 1794. “Medicine,” wrote Haslam, “has generally been esteemed a progressive science, in which its professors have confessed themselves indebted to great preparatory study, and long subsequent experience, for the knowledge they have acquired.” Willis, in defiance of human experience, claimed unparalleled success right from the start. The Bethlem data also undercut Willis’s pretensions by showing much poorer results for older patients than for persons in their teens or early twenties. The odds for a man of age fifty, such as King George, were 4:1 against recovery. And among patients admitted (against stated policy) after more than a year of illness, Haslam found not a single lasting recovery.

When the reader contrasts the preceding statement with the account recorded in the report of the Committee who have attended His Majesty, &c. he will either be inclined to deplore the unskilfulness or mismanagement which has prevailed among those medical persons who have directed the treatment of mania in the largest public institution in this kingdom, of its kind, compared with the success which has attended the private practice of an individual; or to require some other evidence, than the bare assertion of the man pretending to have performed such cures.*

The footnote referred to Willis’s testimony in 1789, where he claimed, without evidence, cures at a rate far surpassing Bethlem’s most modern results.11

There is no agreement among scholars or psychiatrists on the cause of the king’s illness or on the significance of Willis’s treatment for his temporary recovery. He continued to be troubled by intermittent mental illness and during the 1810s was so disabled that his son, the future George IV, was appointed to govern as regent.

A Statistical Specialty

The infrastructure of public and private medical numbers on which Black relied was still emerging. In Britain, financial and insurance calculations, which relied on extensive tabular data, had become quite sophisticated by early in the eighteenth century. Medical institutions were not exempt from the demands of financial reporting.12 Patient records were another matter. Medical records of insane asylums were gradually regularized in Europe and North America during the first half of the nineteenth century. In 1815, a parliamentary committee reported scathingly on the efforts of English asylum officials to conceal institutional records. Along with eyewitness accounts of female patients kept naked in bare, squalid cells behind a gate whose keeper claimed no access to a key, the committee called attention to the concealment and falsification of patient books. A magistrate, Godfrey Higgins, describing his efforts to inspect the Yorkshire Asylum, explained when asked about patient registration: “There was a set of books regularly kept by the apothecary, and also another set by the steward, both of which purported to be a correct account of admissions of patients, and how they were disposed of, but I have reason to believe that those accounts were false, and that they were kept falsely on purpose.” He pointed to discrepancies between closely held books and the official ones, providing a basis for muckraking newspaper accounts. A steward refused to deliver up the books he kept, claiming they were his own property, and later testified that he had destroyed them. Just after the court of governors ordered an investigation of the Yorkshire Asylum, its buildings caught fire, immolating several patients along with the record books.13

These 1815 hearings soon acquired a place in historical accounts as the moment when old abuses in the public asylums were washed away, when the institutions at last became responsible and humane. They presaged a monumental expansion of asylum systems, first in England and France and soon afterward in other parts of Europe and North America, that was to go on for 150 years. While public asylums typically fell to the charge of regional governments such as the American states or English counties, they have a notable place in the genesis of the welfare state, first as curative institutions showcasing public investment in a healthy citizenry, and then as custodial ones to protect the population from degeneracy. In both guises, asylums and hospitals helped give shape to new standards of public accountability. Those developments provided essential background to the development of asylum statistics of heredity.14

Patient accounts as well as financial ones appear often to have been driven by external, bureaucratic demands, but they had also a medical logic. The English physician Thomas Percival, in his 1803 treatise Medical Ethics, spoke of recordkeeping as integral to sound medical practice. Keeping statistics was for him an ethical imperative, reflecting medical obligations to patients. A physician or surgeon, he wrote, should draw up an account of every case that is “rare, curious, or instructive.” Hospital registers ought to include three tables: one for admissions and outcome, a second for illnesses treated, and a third breaking down patients by age, sex, and occupation. These would advance knowledge of healthy and unfavorable “situations, climates, and seasons,” the effects of particular trades and manufactures, and the outbreak or cessation of epidemics. Finally, “physicians and surgeons would obtain a clearer insight into the comparative success of their hospital and private practice; and be incited to a diligent investigation of the causes of such difference.”15

Percival’s sense of the hospital as a place for advancing public health applied well to mental hospitals, which already were becoming exemplary sites of statistics. The most fundamental, and the most ubiquitous, object of their tabulations was the flow of persons through the institutions and the outcomes of their treatment, providing, in effect, a medical balance sheet. Tables could demonstrate the value of these institutions, measured as the number of persons cured of this terrible disease who could return to work and family. The register of causes seemed at first less fundamental, but causes were routinely included in case reports as potentially relevant to treatment. Alienists advised the public to avoid behaviors, such as overwork and excessive drink, shown by statistics to induce mental illness.

Asylums also were the primal site for statistical knowledge of human heredity.

The Causes of Insanity

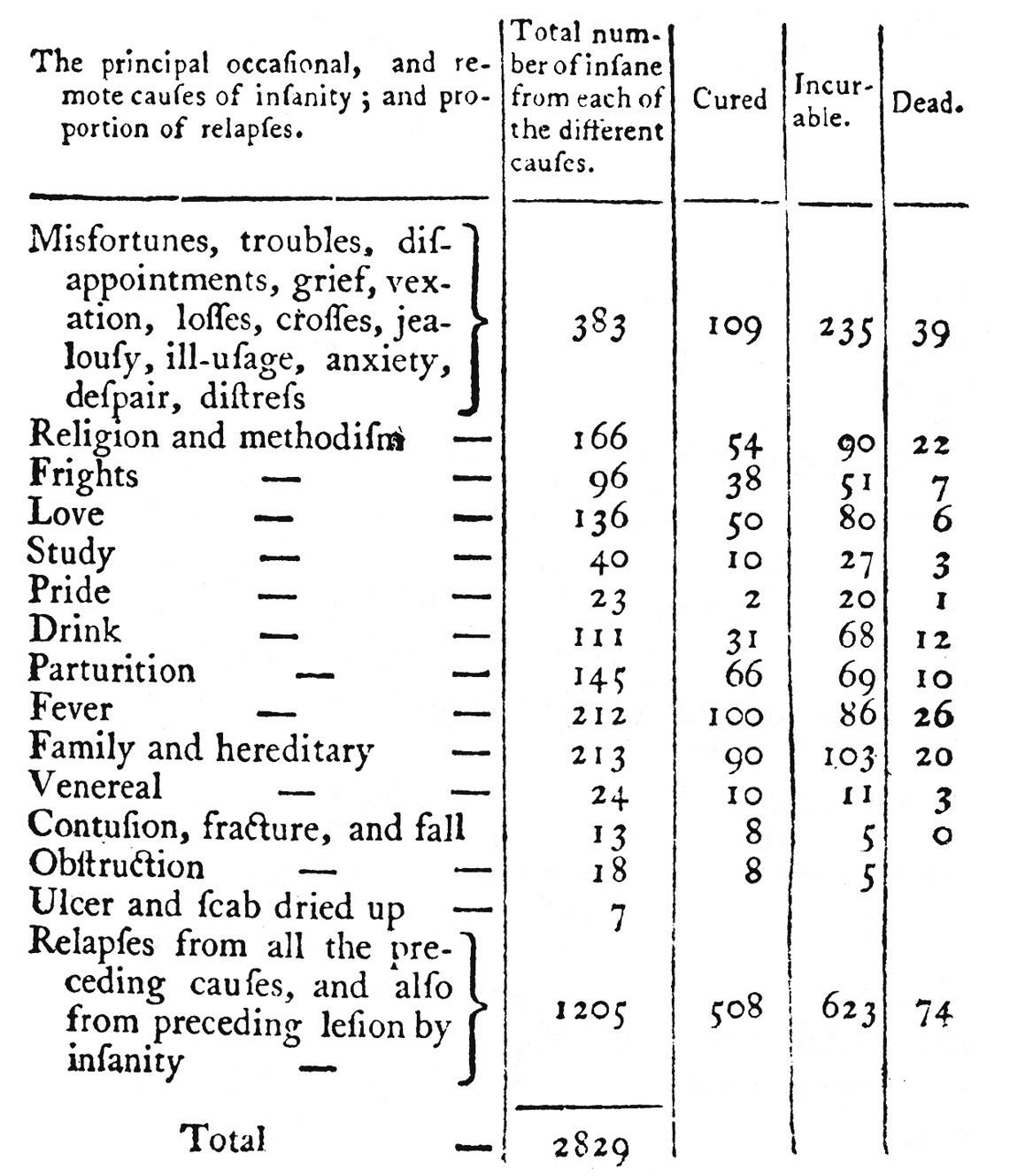

The earliest known statistical table of causes of insanity appeared in Black’s new (1789) edition of An Arithmetical and Medical Analysis of the Diseases and Mortality of the Human Species. In the 1788 edition, he had presented causes and numbers in paragraph form. Medical tables go back at least to John Graunt’s well-known 1662 report on deaths and their causes, based on the London bills of mortality. Until about 1840, most asylum tables were little more than simple tallies, for example, of assigned causes. Black, however, seized the opportunity to build in a second dimension and in this way to relate causation to the urgent question of curability.16 Already in 1788, he had noted with surprise that those with “hereditary insanity . . . seem to recover nearly as well as from the less inherent causes; there are several instances of recovery when hereditary from the parents on both sides.” In 1789, he repeated the thought while omitting the suggestive word “inherent,” which points to internal sources of illness. Black sought out but could not find an anatomical explanation for the “latent predisposition or frailty in the recesses of the brain, which render some more than others liable to this mutiny of reason.” Although the mechanism was hidden, its incidence could be tallied. “Family and hereditary” was, apart from a grab-bag list of miscellaneous troubles and disappointments, his most important cause. Black’s medical histories listed “predisposing and occasional causes” not just for insanity but for most of the diseases he described. As source for the causes of insanity, his table relied on the Bethlem registers, that is, on Gozna’s unofficial book. He elaborated that Gozna acquired this information through inquiries to family members.17

The historian of madness Roy Porter once remarked that the causes on such lists were already familiar to writers on insanity two centuries earlier. Black doubted their validity. “Most of the proximate causes assigned in authors for madness, are mere hypotheses; and of no active use to the community, or to medicine.”18 Haslam, though refraining from the compilation of tables of causation, undertook to check and to improve his data. He worried less about ignorance than mendacity:

FIGURE 1.1. Table of causes of insanity by William Black. This table may be the first ever to list and give numbers for causes of insanity. Black, one of the leading medical statisticians of his day, went beyond adding up causes to show the bearing of each cause on the prospect of a cure. From Black, Arithmetical and Medical Analysis, 133.

When patients are admitted into Bethlem Hospital, an enquiry is always made of friends who accompany them, respecting the cause supposed to have occasioned their insanity.

It will readily be conceived that there must be great uncertainty attending the information we are able to procure upon this head: and even from the most accurate accounts, it would be difficult to effect. The friends and relatives of patients are, upon many occasions, very delicate upon this point, and cautious of exposing their frailties or immoral habits: and when the disease is a family one, they are oftentimes still more reserved in disclosing the truth.

Fully aware of the incorrect statement frequently made concerning these causes, I have been at no inconsiderable pains to correct or confirm the first information by subsequent enquiries.19

The assignment of hereditary and other causes depended principally on observations of family members or close acquaintances and sometimes on opinions given by the patients themselves. The inheritance of insanity, in the basic sense of tending to run in families, was no discovery of medicine or of statistics but an accepted fact of everyday life. Even as professional knowledge, it belonged as much to law as to medicine. Insanity was highly relevant to another kind of inheritance: the right to control property and to pass it on to the next generation. Already in Black’s day, medical jurisprudence was keenly alert to the problem of inherited insanity. John Johnstone, who published a treatise on the subject in 1800, referred to madness as “the most constant and persevering” of hereditary diseases, one whose taint can persist right though a generation that has escaped it. He even called the “hereditary disposition to madness” a “fair ground of evidence in cases of imputed derangement of mind,” meaning that a court could argue backward from evidence of family insanity to the mental state of the criminal.20 Decades later, the life of the scoundrel and delusionary Charles Guiteau was minutely documented in preparation for his 1881 trial for the assassination of the American president James Garfield, yet the legal judgment as to his mental competence seemed to hinge on a demonstration that his condition was inherited.21

Haslam also wrote on medical jurisprudence, and in the second edition of his book on madness he complained of critics who balked at anything less than complete knowledge of the laws of heredity. There is no “infallible transmission” of mental disease, he conceded. It is not possible to specify why the hereditary tendency skips generations and how the sex of the affected parent affects its transmission to sons versus daughters. Despite these mysteries, he continued, hereditary transmission was well known from human experience and from the evidence of cattle breeding.

In illustration of the fact, that the offsprings of insane persons are, ceteris paribus, more liable to be affected with madness than those whose parents have been of sound minds; it was my intention to have constructed a table, whereon might be seen the probably direct course of this disease, and also its collateral bearings: but difficulties have arisen. It appeared, on consideration, improper to attempt precision with that which was variable.

And yet it was not too soon to face the implications of inheritance of insanity and even to take action to block its reproduction. “The investigation of the hereditary tendency of madness is an object of the utmost importance, both in a legal and moral point of view. Parents and guardians, in the disposal, or direction of the choice of their children in marriage, should be informed that an alliance with a family, where insanity has prevailed, ought to be prohibited.”22

French Tables of Hereditary Insanity

Black’s statistics of mental illness were unmatched for decades. His table of causes, however, made less of an impression on alienists than one compiled in 1816 by Esquirol for his entry on insanity (folie) in a massive medical encyclopedia. Perhaps Black was too early; even Esquirol’s table achieved fame mainly as reprinted two decades later. Paris medicine led the world in those years, and Esquirol had succeeded Pinel as France’s most respected alienist, whereas Black never worked as an asylum doctor. Like Pinel, Esquirol taught that insanity could be cured and that a calm, ordered life was an important part of the therapy. He was especially alert to “moral” causes of insanity, such as domestic sorrows, political events, and wounded vanity. The disproportionate number of cases he assigned to heredity, nevertheless, tipped the balance in favor of physical causes.23

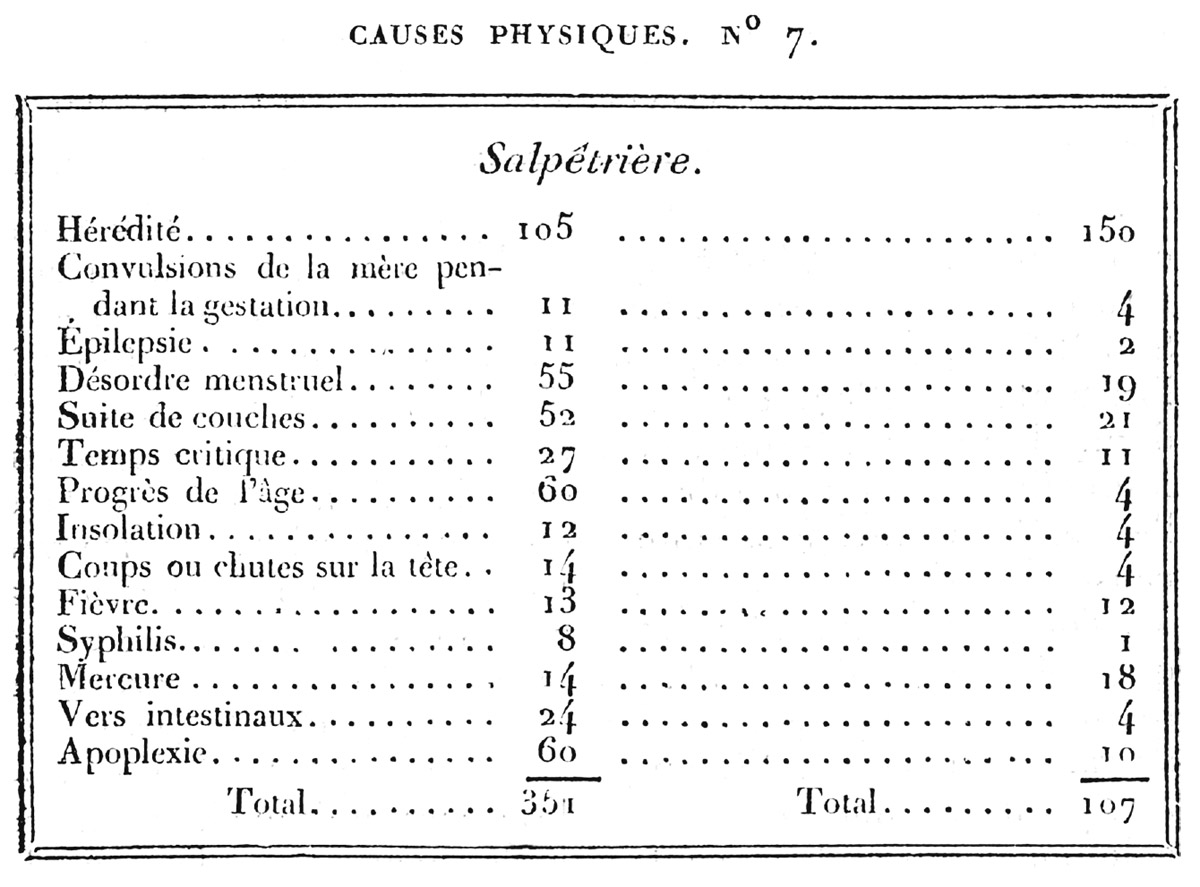

FIGURE 1.2. Étienne Esquirol’s 1816 table of physical causes of insanity. His neglect of arithmetic accuracy cannot explain why the number of hereditary causes in the righthand column exceeds the total of all causes. Other listed causes include maternal convolutions, reproductive and menstrual irregularities, fevers, blows to the head, old age, intestinal worms, and apoplexy. He provided moral causes in a separate table. From Esquirol, “Folie,” 178.

Esquirol’s table of causes appears weirdly incomprehensible. The confusion begins with the inaccurate sums. These discrepancies are much diminished, though they do not disappear, if we ignore the first and largest entry on each list: heredity. Flawed arithmetic cannot explain how, in the right-hand column, the figure for heredity (150) exceeds the total for all causes (107). Silently, he must have treated heredity as a different sort of cause from menstrual disorder, advancing age, or apoplexy. Alienists of this era often classified heredity as a “predisposing” cause, which acted only in combination with an “effective” or “triggering” cause. Physicians used the Greek term “diathesis” for susceptibilities linked to bodily constitution, and Esquirol appears to have been thinking in these terms. Although he declined to mark off predisposing causes in his table, he clearly viewed hereditary causation as not quite commensurable with fevers and falls.24

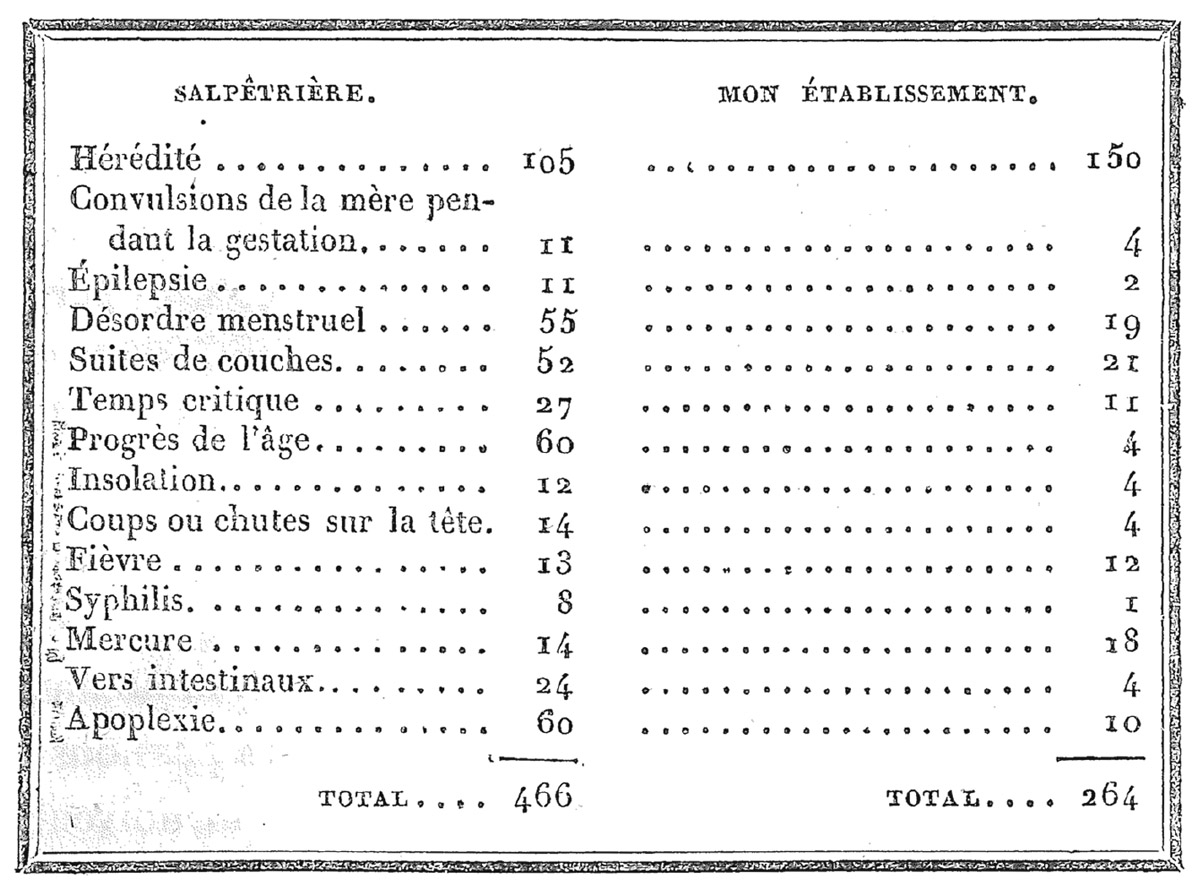

FIGURE 1.3. Étienne Esquirol’s table of physical causes, reworked for his chef d’oeuvre, Des maladies mentales (64). In correcting the arithmetic, he simply added the hereditary cases with other physical causes and thereby effaced his basic distinction between precipitating causes and hereditary ones.

Esquirol’s magnum opus, published in 1838, brought together his many papers and reports. The chapter on insanity added not one unit to his original table. He now made La Salpêtrière into the heading for the left column and inserted mon établissement (my establishment) on the right. In correcting the arithmetic, he set aside issues of incommensurability and simply added in the numbers for heredity, raising the total for his private mental institution from 107 to 264. The revised table thus privileged the logic of addition over the logic of causation, provoking a later German critic to complain of the incoherence of tables whose categories are not mutually exclusive.25

It is unlikely, Esquirol wrote, that the figure for heredity at La Salpêtrière could diverge so widely from that for his private patients. He attributed the discrepancy to indigent women at the hospital who, he said, were unable to supply hereditary information and sometimes did not even know the names of their parents. His paying patients were of quite a different class. It seems that he relied on the patients themselves, even the impoverished women, for much of his causal information. For neither group is there any indication that he followed up with probing questions or investigations to improve his tables. The numbers would always be imperfect. The true importance of hereditary causation, he declared, must exceed what the tables show. Yet it was already at the top of his list. He concluded his 1835 report on the Charenton Hospital: “Of all illnesses, mental alienation is the most eminently hereditary.”26

Nineteenth-century asylum figures on heredity were usually put forth as if anchored in raw data concerning diagnosable conditions of patients and their families. Both Esquirol’s original tables and the revised ones reveal tensions between his understanding of hereditary causation and the requirement to work arithmetically with data as he received it. The discourse of heredity, unalterably numerical, was structured by tabular forms and numerical reasoning. Although this emphasis was sometimes interwoven with questions about objects and processes of heredity, the prime mover here was data practices.