CHAPTER 3

New Tools of Tabulation Point to Heredity as the Real Cause, 1840-1855

No question is so frequently put to the physician of a Lunatic Asylum as that which calls upon him to state the most productive cause of insanity. Those who are most familiar with insanity, find themselves the least able to reply to this question.

—Joseph Workman (1860)

The mission of insane asylums, to check and reverse the growth of insanity, was not limited to treatment. Right from the start, asylum superintendents took on the charge to block, somehow, the springs of insanity. Their tables of causes, based mainly on lay attributions, were featured in annual reports, but many of the causes assigned, especially “moral” ones such as disappointments in love or business, were never convincing to asylum doctors. They focused particularly on drink, masturbation, and heredity, with heredity gradually gaining the advantage over its rivals. Almost no one doubted the reality of hereditary transmission, for which the evidence came down to observations of similarly afflicted relatives.

Heredity had the feel of a deep cause and yet seemed to be supported by ordinary experience. It was simultaneously scientific and popular, and it worked well with statistics. The data of heredity provided a basis for international collaboration among alienists. The principal advantage in the investigation of causes was their access to records of their own institutions and to the data and conclusions of far-flung colleagues. Hence, the push for science and for the medical-administrative rationalization of asylums was never merely inward-looking. French, German, American, and British alienists all founded organizations or journals in the 1840s. They were not just willing but eager to share their data and findings. With the support of ministries and boards of visitors, they cultivated habits of travel to keep up with the latest remedies, architecture, science, and techniques for keeping order. They emphasized statistics as their prime tool for assessing causes of insanity as well as results of asylum care. By 1840, they were beginning to discuss ways to improve hereditary data by tracking down the relatives of patients. While many alienists hesitated to merge the numbers of different institutions, they were keenly interested in enhancing their techniques for gathering and ordering data.

Tracking Heredity

The case books at the York Retreat document the origins of systematic hereditary investigation as something more than recording what informants told them. The first of these, extending from 1796 to 1818, is a small, unprepossessing volume, about 8 by 6 inches, meager as a storehouse of information. The records of these patients, though sometimes extending over decades, rarely fill as much as a single page. An 1802 watermark indicates that the first pages were filled in retrospectively. Many of the earliest patients had already been disturbed for years, and their prospects were bleak. Patient 1 returned home for a time but died finally in confinement. Patient 2, described as kindly and imaginative and noted for her vivid descriptions of “figures in the clouds & fire” and of strange remedies (these perhaps did not have to be imagined), lived out her life there. The third patient improved at first but soon turned melancholy and ended his stay as the Retreat’s first suicide, grounds for the dismissal of a neglectful attendant.1

Case 9 is notable for the first appearance of spidery, slanted annotations in black ink. The patient had been marked “Hereditary” in 1813, but there is a later insertion: “& has had a son deranged since, see 599.” Patient 599 was admitted about two decades later. For case 18, the spidery hand introduced “Hereditary?” as a hypothesis, adding “Cousin to Tho’s and Benj’n Atkinson.” Patient 19 was retrospectively cross-referenced to page 220 of Tuke’s Description of the Retreat, published sixteen years after her admission.2

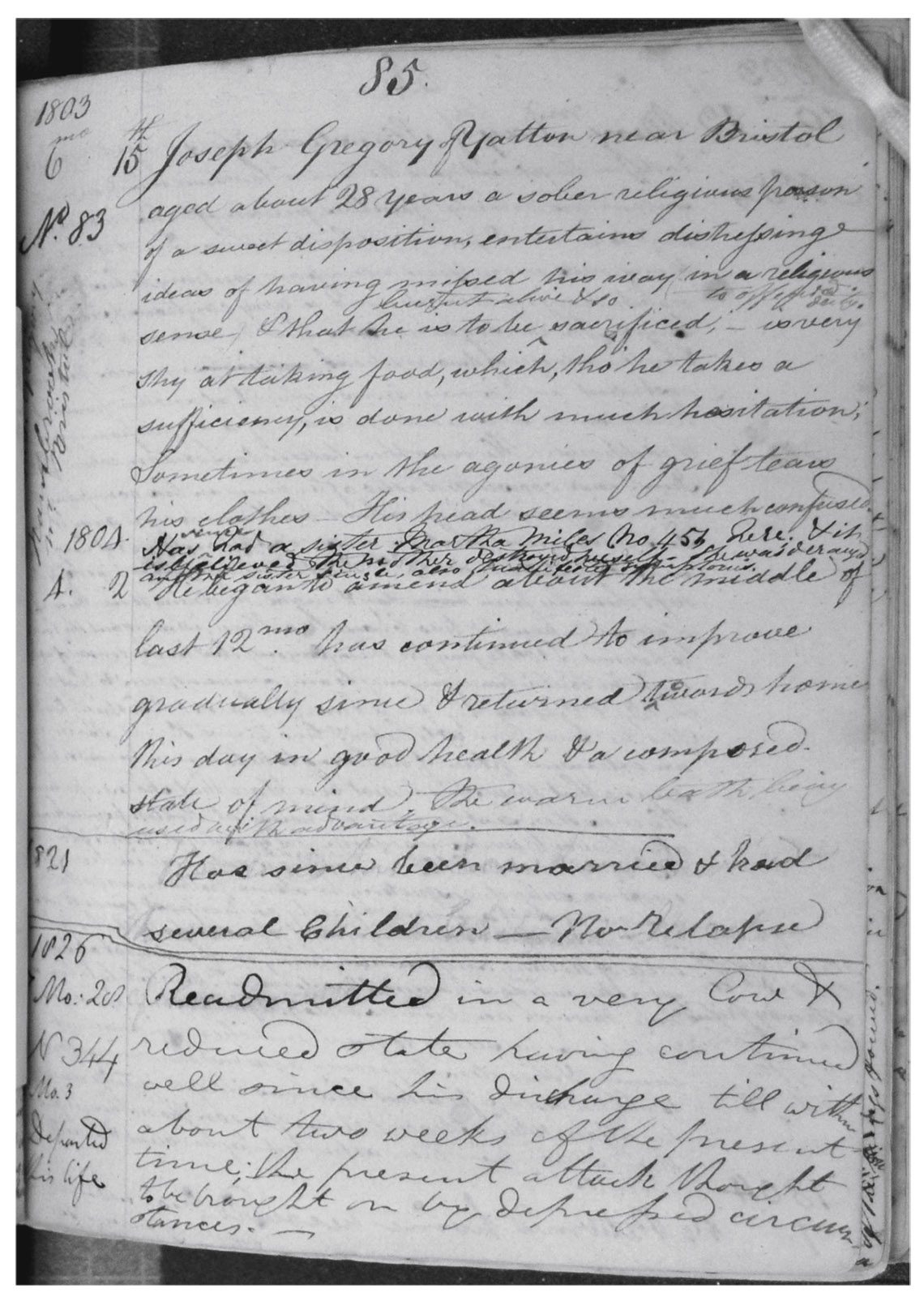

FIGURE 3.1. Retreat at York, Case Book, Patient 9. About 1840, John Thurnam inserted, for a case already identified as hereditary: “& has had a son deranged, see 599.” Such insertions demonstrate his active interest in patient heredity. Reprinted from an original in the Borthwick Institute, University of York, RET 6/5/1/1A Case Books.

These inscriptions haunt the case books. They speculate about hereditary origins, supply names of disturbed relatives, track the subsequent career of discharged patients, and record results of postmortem dissections. They tell of “strong hereditary decay” in patient 28, whose father was “very eccentric and he is nearly related to the Waring & Moxham families,” the maternal cousins of James Moxham. Patient 83 “had a sister Martha Miller No. 454 here & it is believed the Mother destroyed herself. She was deranged and another sister, single, also manifested symptoms.”3

Patient 236, after discharge, “remained, to say the least, very singular, carried a basket of wares & became a sort of hawker about the country. She is believed, 1840, to be still living.” In the second case book, the record for a patient admitted in 1833 has inscribed in bold letters, then thin ones: “Retrospective History. Some hereditary tendency to insanity appears to exist especially on the Maternal (Wilson) side,” followed by remarks on the patient’s childhood, religious experiences, strange beliefs, and unconventional experiments.4

The hand that recorded these comments is easily surmised. John Thurnam was appointed medical superintendent of the Retreat in 1838. His scheme of standardized records, as we have seen, put special emphasis on tables of presumed causes of insanity, and his statistics point to an overwhelming concern with heredity. They show 70 patients with heredity as the only predisposing cause, 72 with heredity in combination with some other cause, and 71 more involving collateral relatives rather than direct ancestors, constituting, in total, 51% of his patients. He insisted that even this number, based on incomplete knowledge, was by no means the limit. For practical as well as scientific reasons, he aspired to investigate still further. He was, by his own account, tireless in tracking down families, never accepting the mere declaration of a relative, always pursuing “more private information” and listening for what was well known in the community. The predisposing causes, he explained in a long introduction to his tables, “have attracted less attention than the exciting, and from their frequently insidious character, are often altogether overlooked” yet “they are frequently the most important” and “they are also, in many instances, more easily guarded against.” Hereditary causation, in short, left room for effective intervention.5

Thurnam’s investigations of insane heredity commenced two decades prior to Darwin’s Origin of Species and a quarter century before Francis Galton became curious about hereditary genius. Although his family inquiries and his organization of data appear original, his hopes of checking the reproduction of human defects were already becoming familiar. George Chandler, who succeeded Woodward at the Worcester asylum, wrote in his annual report for 1846: “The prevention of insanity should be the aim of an enlightened community as well as its cure. This means obeying the laws of health. . . . Hereditary predisposition to disease, which is either inherited from ancestors or acquired by the parents themselves, by abuse of their own physical systems, is transmitted to the lineal descendants.”6 In 1835, James Cowles Prichard, physician-ethnologist and outspoken opponent of the slave trade, summed up the import of his humane and learned book on insanity with this thought:

FIGURE 3.3. Retreat at York, Case Book, Patient 83, John Thurnam’s insertion: “Has had a sister Martha Miller No. 454 here & it is believed the Mother destroyed herself. She was deranged and another sister, single, also manifested symptoms.” Reprinted from an original in the Borthwick Institute, University of York, RET 6/5/1/1A Case Books.

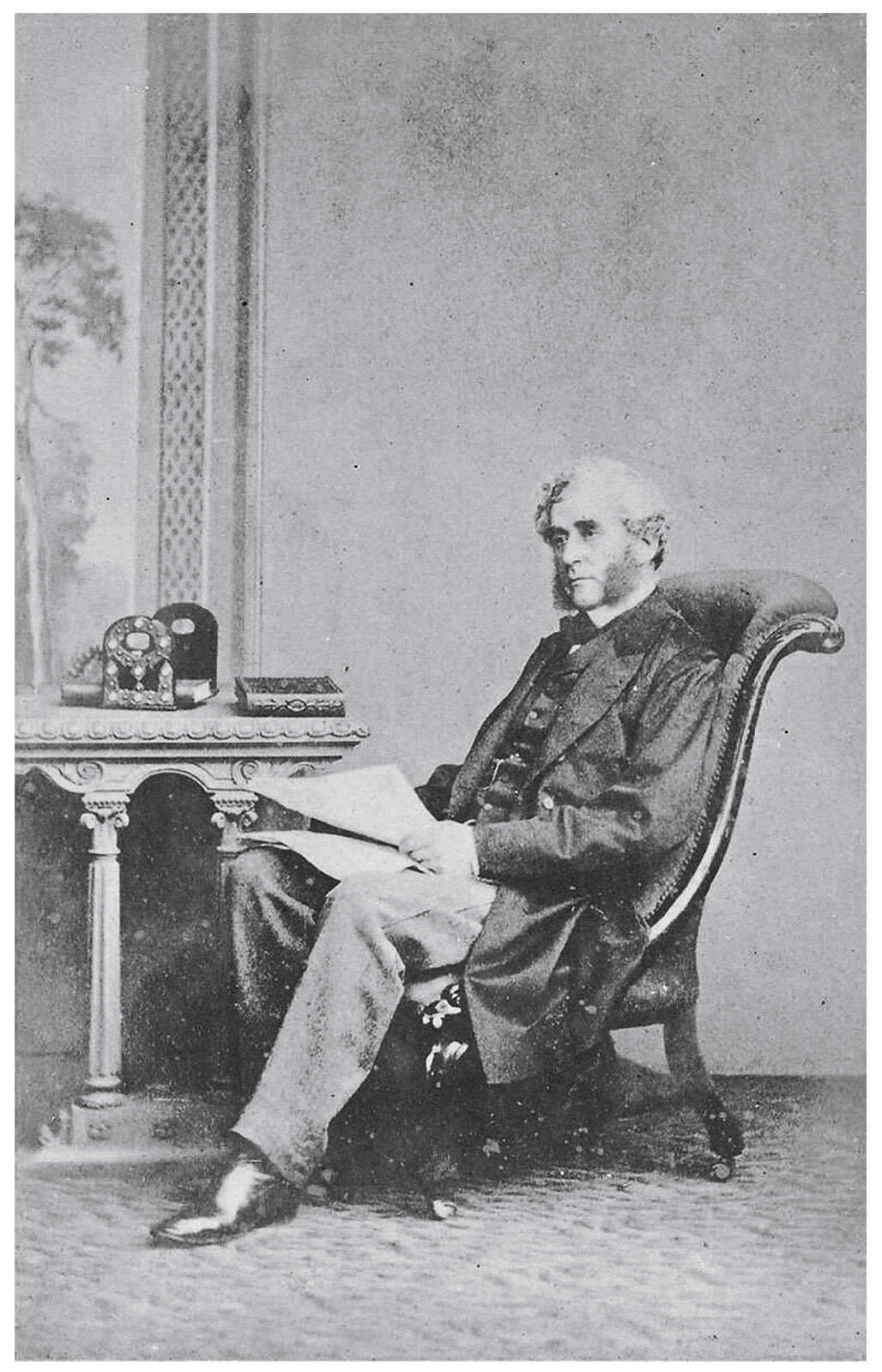

FIGURE 3.4. Photograph of John Thurnam (1810–1873). Thurnam was among the very first medical superintendents of an asylum to investigate the behaviors and mental conditions of relatives of his patients. He was also an energetic statistician and advocate for uniform categories. Reprinted from an original in the Borthwick Institute, University of York, RET 1/8/7/12.

In adverting to the inquiry, whether any means could be adopted that would tend to diminish the extent of this evil, we are struck by the obvious consideration that the numbers of deranged persons in the community might be very much lessened if it were possible to regulate or establish any surveillance over the marriages of the lower orders, or if some measures could be adopted to prevent the propagation of idiotism and an hereditary tendency to madness. Idiots who are at large wander about the country, and the females often bear children.7

Thurnam’s originality was the fruit of his determination to track down the relatives of his patients and his skill in organizing the resulting data. He recognized the insane asylum as an ideal site for this kind of work. His advantage over others with similar ambitions owed much to the special population he treated. The Retreat, a Quaker institution, mainly served members of this close-knit religious community, which was his community too. He was thus able to trace family members across generations, whether they had been institutionalized or not, and to check out vague or uncertain claims. The concentration of mental illness in his institution enabled the families to be treated as model organisms for hereditary research.

While Thurnam carried out this research within the asylum he directed, his work coincided in time with the formation of national and international communities of asylum physicians engaged in research on patient heredity. If their backgrounds were mainly medical, their tools and methods were social and statistical. He provided an important model for their work and a basis for comparing and combining results.

Traveling Knowledge

“An interval of professional leisure, during the last summer, enabled me to gratify a long cherished wish of seeing a little of the Old World, and especially its institutions for the care of the Insane,” wrote Isaac Ray in 1846. He had just been hired at the Butler Hospital for the Insane in Providence, Rhode Island.8 Government ministries and boards of overseers authorized these alienists’ holidays to familiarize new superintendents with the latest techniques of asylum management. Psychological medicine, if not quite a research specialty, formed a distinct branch of the medical profession. Pliny Earle, after taking his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania, continued his studies in Paris, where he was won over to Pinel’s moral treatment. Upon his appointment as superintendent of the Quaker asylum in Frankford, Pennsylvania, he set off on a European tour featuring some of its most notable institutions. While Bethlem, still wary of spectators, would not let him through the gates without an appointment, most welcomed him. In England, he visited asylums at Hanwell, York, the West Riding of Yorkshire, and the York Retreat, which he particularly admired. He proceeded to Amsterdam, Utrecht, and Antwerp, the great Paris hospitals, Milan, Venice, Malta, and Constantinople. His travel narrative bore, as subtitle, An Essay on the Causes, Duration, Termination, and Moral Treatment of Insanity. With Copious Statistics. Published in 1841, it included a mix of visual impressions, recollections of conversations, excerpts from other eyewitness accounts, and fragmentary statistics. He added a descriptive inventory of American institutions as well as Old World ones that he could not visit, extending as far as Cairo. In 1853, Earle again described an asylum tour, this one through seventeen German and Austrian institutions which, apart from Siegburg, near Cologne, were little known in America. He was impressed by German efforts to make asylum medicine a special field of study. He also commented on local censuses of the insane organized by institutions in Silesia and in Oldenburg.9

Medical tours, especially to France, were common for antebellum American physicians. Alienist visits proceeded in every direction. European alienists traveled often to neighboring countries, and sometimes to America, whose asylums, like its prisons, gained a degree of international renown. These New World institutions were adept at self-promotion. Behind the classical columns and pediments of a US state asylum building, however, the visitor might be confronted with dark stinking rooms and noisy tumult.

Everywhere, in this business, appearances could be deceiving. On a beautiful September day in 1869, the lead editor of the Allgemeine Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie (AZP), Heinrich Laehr, floated serenely on a gondola to the Venetian hospital of San Servolo. The island setting and Mediterranean climate would appear to his countrymen as an impossible dream, he remarked. Inside, it was a depressing place. The patients arrived despondent and fearful, most of them suffering from pellagra, whose treatment they had put off until it endangered their lives. The archives there confirm Laehr’s description. The remedy for pellagra was simple: a better diet. Patients who did not die improved rapidly. And then, the doctors complained, they insisted on leaving before the cure was complete.10

Even in El Dorado, the alienist’s paradise was elusive. In 1870, when California got serious about containing mental illness, it sent the newly appointed commissioner to visit forty-five American asylums and ninety more in Canada, Bavaria, Austria, the German states, Switzerland, France, Belgium, Holland, England, Scotland, and Ireland, in quest of medical and architectural instruction. His state would need “all the light that the wisdom and experience of the learned men in other States and countries could shed.” His own statistics showed a disturbingly high rate of lunacy, already a California stereotype. In the 1880s, an Australian achieved the ne plus ultra of asylum tours, filling a 1,567-page volume with his observations “from all parts of the world” under the fitting title Lunacy in Many Lands.11

FIGURE 3.5. Artistic rendering of the Ohio Lunatic Asylum in Columbus, printed as frontispiece to the annual report from its opening in 1839. Most American states constructed new buildings, which could be quite grand, for their mental patients. The interior was typically less lovely than the façade. Courtesy US National Library of Medicine.

Printed Reports and Circulation of Data

The circulation of documents was equally central to professional and scientific exchange. Annual and multiyear reports provided information on practical topics such as building and garden layout, facilities, schedules, and work routines. They also supplied patient statistics in a familiar form, providing material for waves of excerpts, digests, and comparative tables. National journals of asylum medicine, three of which sprung up almost simultaneously in 1843 and 1844, watched each other closely. The networks of outreach and exchange can be traced through their contents, which reveal an intense, shared concern with the data of insanity and its causes. The Annales médico-psychologiques (AMP) called attention to patient heredity in Jules Baillarger’s editorial introduction and made frequent reference to statistics, both at home and abroad.12 The 1844 volumes include a news clip on the tripling of the burden of insanity in England in just twenty years and reviews of the statistics of Bethlem.13 Having taken notice of the new AZP in 1844, the French journal printed an extensive summary of its first volume in 1845, with particular attention to asylums in the German states of Baden and Württemberg, across the Rhine from French Alsace. An alienist at La Salpêtrière contributed a sixty-page narrative of his visit to the well-known asylum of Illenau in Baden.14 The first volume of the American Journal of Insanity (AJI) celebrated the launching of the French AMP and, a few months later, of the German AZP. It reported on hereditary investigations from Paris and statistics from the asylum of Saint-Yon in Rouen.15 These are only a few examples, most from a single year, of news exchanges that went on for decades.

The Rouen institution was directed by Maximien Parchappe, whose devotion to asylum statistics in France may be compared to Thurnam’s in England. In an 1839 study of the causes of insanity, Parchappe brought together reports from the United States, Italy, and Belgium, as well as France, for the sake of more inclusive numbers. He was already looking forward to a golden age of asylum statistics in consequence of all the new institutions required by the 1838 French asylum law.16 In 1844, he published a data-filled annual report on Saint-Yon, followed the next year by a coauthored one with his colleague Lucien Deboutteville extending from 1825 to 1843. Thurnam, in a review, commended its cosmopolitan spirit of statistical emulation as well as its copious tables, which he described as a model for the multiyear report, demonstrating how the statistics of insanity could be raised above mere routines of recordkeeping.17 A comment like this one seems to cast doubt on the value of annual reports, but Thurnam took the opposite view, applauding their recent advances both in number and quality, at home and abroad. The value of these international exchanges, he continued, would be enhanced by greater uniformity, especially of statistics of causes.18

On this issue of causes, Thurnam extended his praise to a recent Danish author, Peter Jessen, whose report on the territory of Schleswig made a compelling case for uniform classification. Jessen found little value in the data on moral causes supplied by impressionable family members. Hereditary causation, by contrast, could be reliably documented, since the evidence of sick family members was medically observable.19 Against the background of whimsical, wavering moral causes, hereditary factors stood as a beacon of hope. Alienists agreed on the reality of hereditary causation, which was underreported, they argued, not on account of an inability of family members to recognize it, but because they had lost contact with their kin or were ashamed to admit an inherited family taint.

Doctors Know Best

Sorting out the true causes of insanity was a great international challenge. Apart from heredity, masturbation was the cause that families seemed most concerned to cover up. Perhaps the recognition of its role might explain away some of the more transitory and less credible moral causes, such as political events and religious excess. Often, the causes they recorded in the admission book were not what they really believed. It was especially hard to escape the roller coaster of spiritual and behavioral explanations.

Amariah Brigham mentioned in 1844 in his second annual report for the state asylum in Utica, New York, that while some insanity had no doubt been occasioned by the French Revolution, the American Revolution, Luther’s Reformation, and South Sea speculation, passing events like these must be of relatively minor importance. He was much more impressed by predisposing causes, above all heredity.20 However, his tables, based on what the families told him, highlighted religious enthusiasm. For example, Millerism, promising an imminent millennium, showed up as a distinct cause in 1844. It surfaced also in Connecticut, whose tables caught the eye of Bénédict Augustin Morel, soon to become famous for his theory of hereditary degeneration. Morel had a reputation for his statistical tables and reviews of reports from other institutions. He commented in AMP on the unhealthy religious doctrines that charlatans inflict on gullible Americans.21 “Spiritual rappings” burst onto the insanity charts in 1851, just months after their first exhibition in Rochester and New York, sending 7 men and 11 women to the Utica asylum. The next year these rappings reached Ohio, where Elijah Kendrick, as superintendent, registered 13 male and 13 female cases “caused by the present popular delusion, ‘Spirit Rappings.’ ” It promptly began to subside: 5 men and 6 women in 1853, then 3 men and 4 women, 1 man and 2 women, until, in 1856, it slipped beneath the dark liquid of lost memory. Kendrick now argued that alleged causes are not always real ones and that the attribution to religion was merely a mask for masturbation.22

Alienists, as respectable people, hated the idea that true religion caused insanity. Could they find a better explanation? Ohio, according to the statistics, was ravaged by onanistic lunacy, more so even than Massachusetts, where Woodward warned of its deadly effects and where Samuel Gridley Howe, writing on idiocy, grouped it with intemperance and heredity as a sin of the progenitors.23 Samuel Hanbury Smith, Kendrick’s predecessor in Ohio and an admiring disciple of Woodward, had already discerned this true basis for what was blamed on religion. “His mind, already weakened by the enervating effects of his pernicious practice, is quite unable to withstand the perturbating influences it is there subjected to, gives way, and fits of maniacal excitement, alternate with periods of dreadful prostration and agonies of despair. . . . During the continuance of the excitement, his distempered fancy prompts the outpourings of rhapsodies of devotion and blasphemy intermingled.”24 Always lurking and rarely acknowledged, masturbation also affected the woman, compromising her essential duty to the health of her children. Such a threat called for strong medicine: “cauterization of the urethra, and blistering the prepuce with cantharidal collodion, accompanied with the steady use of large doses of camphor and lupulin at bed time, and of the tincture of muriate of iron, much diluted with camphor water, during the day.”25

Brigham had complained in the first Utica report that too few authorities “give anything more than the supposed or probable causes.”26 Upon his death in 1849, a new director elevated the charge from doubt to deceit. Relatives of the insane substituted “religious anxiety” for the deadly effects of masturbation. Alienists should ignore unreliable lay witnesses and report causes “as they are developed from the history and progress of the disease.”27 The Glasgow asylum in Scotland emphasized careful recordkeeping as an alternative to reliance on ignorant or dissimulating relatives. He took Thurnam as his model. “From the accuracy, however, with which our records are kept, we are often enabled to trace the hereditary predisposition, in cases where it has been pointedly denied.” The causal force of masturbation, however, was more elusive and tended to recreate those mad novellas from which the alienists longed to break free.28

In gold-mad California, where there often were no relatives to be found, many insane were brought in by sheriffs or constables who knew nothing about them.29 Heredity was practically a closed book in a state populated by lone immigrants. California in the early 1850s, with its unattached young men dreaming of riches, seemed almost uniquely vulnerable to the deadliest moral causes of insanity. “It is fearful to contemplate the amount of mental excitement, the violent passions, the ungoverned tempers and continued turmoil prevailing throughout the entire population of the State,” wrote asylum physician Robert K. Reid. The good side of California—its political and religious liberty—as well as the bad—its unsettled communities—each tended to increase lunacy.30 Reid expected it to trail off as civilization took root, but in 1867 the resident physician G. A. Shurtleff conceded that his state had become notorious for insanity. The profile of causes diverged from the rest of America by its low figure for heredity and high one for masturbation, number seven among causes in the eastern states, and number one in California.31 By this time, Shurtleff was beginning to think that masturbation might be more effect than cause of madness. In the territory, then state, of Washington, it lingered on as a leading cause into the twentieth century.32

Anglo-German Interactions

Thurnam’s book provided an international model for hereditary investigation and, more generally, for organized recordkeeping and statistical calculations. The Retreat had become famous in Germany thanks to Maximilian Jacobi, pioneering director at Siegburg in the Rhine Province of Prussia. The York physicians returned the favor with their praise of Jacobi’s asylum for its subtle effectiveness in inducing even the wealthy to undertake curative labor. They also had a role in the 1841 translation of Jacobi’s book on the architectural layout of asylums. Samuel Tuke introduced that volume with an essay on the disconcerting increase of insanity, which he hoped might finally be approaching its limit. The same year, a German asylum doctor making a tour of British institutions was so captivated by the Retreat that he devoted more than half of his book to a translation with commentary of Tuke’s essay and Thurnam’s newly published Statistics of the Retreat.33

A few years later, Thurnam’s work was featured by the founders of the AZP. In his editorial introduction, the lead editor, Heinrich Damerow, outlined a vision of psychiatry as a collective project to take shape on the pages of his journal. Reliable, unified statistics was to be central to this shared endeavor, a prerequisite for proper institutional planning. He proposed to compile and print annual returns from every German asylum and even foreign ones, so far as possible. A community of statistical investigation, he went on, needed to reach consensus on the forms for collecting and presenting data, a particular challenge in the disunited German state. “Objective” psychiatry required a collaboration of physicians and state administration. Together, they could achieve a unity of theory and praxis, word and deed, idea and execution, Technik and administration. “It appears therefore as one of the tasks of our journal that we German insanity doctors must unite and then work together on the principles and methods of statistical recording of lunatics in Germany.” He called for a uniform, simultaneous census of madness throughout Germany, whose results could be laid down in his journal.34

Comprehensive, unified statistics was thus a key element of Damerow’s vision for German psychiatry. Alienists should continue tracking patients after their release. Carl Friedrich Flemming, second in the editorial collective, foresaw that its pages might in the future supply a rich and useful archive, invaluable to investigators whose findings are otherwise dispersed among so many accounting statements of so many institutions. It could function as a data bank, not just of asylum patients, but extending to lunatics wherever they were found. Flemming, in his introductory mission statement, proposed a set of tables for general adoption featuring disease forms, treatment outcomes, and causes, both physical and psychical. He stressed the need for homogeneous numbers to enable dispersed observers to reason by comparison, and lauded Thurnam’s Statistics for its “superb circumspection.” Every science, he declared, runs through two phases with respect to its numbers: an era of scarcity followed by one of superabundance. As mental medicine entered this second phase, it required principles for gathering facts so that the enterprise would not dissolve into hopeless confusion. German doctors stressed that data are never self-organizing but become meaningful only when shaped by human intelligence. Uncertainties of measurement would clear up with time if only alienists would cast off the dubious practice of passive recording.35

Their vision even included a role for mathematics, provided it was given the right materials to work with. Dr. Karl Reinhold Bernhardi, another admirer of Thurnam, proudly called attention to the 1,151 observations he had accumulated at his asylum in Königsberg. Thurnam had described how cure rates could vary as an asylum filled up with patients, even if medical effectiveness was fixed. Bernhardi explained his reasoning and suggested an improved basis for asylum statistics to avoid spurious numbers.36

Finally, he moved beyond statistics to a logical argument for focusing on predisposing causes. Many moral causes, he explained, lack “objective validity.” Disappointed affection cannot be a true cause of insanity, because most of the time it does not lead to mental illness at all. The passage from disappointment to insanity must therefore depend on a constitutional factor that enables some to withstand the hard blows of fate while others are toppled by a light push. “It is necessary to penetrate more deeply into the darkness and take the trouble to ascertain the sources of predispositions.” What was this underlying factor? In such darkness, the dim light of heredity shone brightly. Heredity did not rest on the surface but lay deep within the organism. Superficial explanations reflecting family experience left questions that could only be resolved in terms of the inner forces of heredity and constitution.37

This sense of a need to get beneath appearances was not confined to German writing. In 1844, Pliny Earle was appointed as the physician at the Bloomingdale Asylum in New York City, one of the oldest American institutions of its kind. He set to work on a comprehensive statistical account of that hospital from 1821 up to his own arrival. This meant, in practice, mining the data for significant conclusions, particularly on the question of causes. He now challenged the old division between predisposing and proximate causes, arguing that it often was impossible to decide which was which. Only heredity, which acted from within, retained its clarity as “inevitably a remote or predisposing cause.” The hereditarily weak individual “will retain the healthy action of his mind until he is subjected to some other influence, more immediate, more active, more potent, and the tendency of which is to derange the physical functions of the system as to impair the manifestation of the mental powers.” Something like a theology lurked in this complex phrasing, which preserved the sanctity and coherence of mind even as the brain disintegrated. Heredity, as a physical cause, could be documented by looking into the health of family members, and sometimes from hospital records. This way of proceeding seemed more convincing than trying to specify the impact of moral disturbances.38

More Than a Predisposition: The Anlage

The first substantive article in the newly established AZP, immediately following Damerow’s mission statement, was Ernst Albert von Zeller’s seventy-nine-page report on the curative asylum of Winnenthal, in Württemberg. Zeller, who published poetry and hymns as well as asylum reports, was its founding director.39 Before assuming his new duties, he set off on a tour of institutions in England, Scotland, and France as well as several German states. Right from the start, he was skeptical of causal claims based on official tables. In his second report, he said it was impossible to distinguish cures from mere recoveries. In his first, he announced that a “tabular overview of the causes of mental disturbance” seeks what is impossible. Rather than comprehending the true convolute of causes, it picks out as cause the first notable symptom.40

Zeller could not simply run roughshod over established practices. His reports included statistical tables that were hard to reconcile with his own avowed principles. He was seeking a deeper basis of understanding. In his third triennial report, the one that found its way into Damerow’s ambitious new journal, he listed not causes but “impulses [Momente] that can be seen as nearer or more remote causes.” The first cause on his list was erbliche Anlage, a historically important term with well-developed medical roots. The usual translation, “hereditary predisposition,” merely skims the surface of its meaning.

The great nineteenth-century Deutsches Wörterbuch (German dictionary), by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm identified the original sense of Anlage as a laying on (Anlegen), of taxes, for example. Even as this meaning was preserved, it developed an inverted sense. In terms of the irresistible horticultural metaphor, Anlage began to refer not just to the seed that is sown but to the garden bed receiving it. Anlage, in this sense, signifies a potential that may or may not be realized, the soil in which certain seeds will grow and flourish while others fail to sprout. The human Anlage could be purely personal, but hereditary (erbliche) Anlagen were, according to Zeller, the “most frequent and the most important developmental impulses [genetische Momente].” He added that mental illness rarely arises from such factors alone. Just one female and four male cases from his institution could be attributed to this Anlage by itself. However, 75 men and 60 women owed their insanity to heredity in combination with “other circumstances.” Hereditary causation may be direct or remote, and hereditary predispositions are not always noticeable in the family.41

In the instructions for registering patients, drawn up in 1853 for the new asylum of Karthaus-Prüll in Regensburg, Bavaria, the authorities laid out a plan for comprehending the Anlage. Item 7 in a list of facts to be recorded for a new patient addressed the question of causation.

One must, in particular, investigate and record the relationships in which the patient has lived from earliest childhood, the causes that once impressed themselves on his body and mind, and the dispositions that supposedly could have provided an Anlage to mental illness, and then finally the proximate causes of the actual outbreak of mental derangement. Then, if possible, one should determine through what concurrence of inner Anlagen and external instigations the illness may have been generated and developed.

These instructions specified that the Anlage could as well be mental as corporeal and that it referred to “capacities and powers” arising during maturation from childhood to the outbreak of illness, not only to “original or congenital ones.” Finally, the text pointed specifically to the erbliche Anlage, which it categorized among mental (rather than bodily) causes that act from the earliest years.42 A similar document from Munich, drawn up as an appendix to the printed rules when the institution opened there in 1859, called for information on the “Anlage for similar diseases as far as the grandparents” as well as “Anlagen and direction of the mind and disposition, temperament, education, condition, favorite pursuits, social intercourse, morality, and religiosity.” The Anlage was an alternative to confusing, superficial causes arising from miscellaneous life experiences. Within a few decades, the hereditary Anlage would appear as something concrete, a factor or element rather than merely a precondition. The 1876 revision of the Munich rules mentioned simply “family Anlage to disease, especially brain and nerve diseases” and then “mental Anlagen.” In the early twentieth century, the Mendelian factor was called, in German, an Anlage or Erbanlage, and in psychiatry, at least, this term remained more common than Gen (gene) in the 1930s.43

Zeller called for observation informed by a deep understanding that could grasp things in their complexity. He aspired to comprehend how heredity worked in the transmission of insanity. Flemming pointed out in 1838 that the recurrence of parental mental disturbance in children and grandchildren was a well-confirmed fact, and yet that with a correct upbringing, these descendants might be protected. The erbliche Anlage was no mysterious curse, he insisted, but “a pathological condition or a disposition to develop such a condition.”44 Zeller stipulated that an Anlage was strengthened by exercise. “Here is one more reason why inheritance of mental disturbance is so prominent, for the procreator is, as a rule, also the educator. In the same way, a dormant Anlage for mental disturbance may be awakened early and nurtured by the parent’s unreason.”45 The complexity of the Anlage seems better suited to narrative than to counting, and Zeller put no faith in simple answers. To pronounce a patient recovered is a subtle determination, he insisted, and to attribute the recovery to treatment is another. The figures in tables are always somewhat fuzzy, since every institution categorizes in its own way. Tallies, then, can never replace thinking. “And yet in the eyes of the world there is no way to get a grip on the effectiveness of an institution but with such numbers.”46

The eyes of the world, it appears here, were distinct from the eyes of science or wisdom. On questions of cures and of causes, worldly eyes peered through bureaucratic spectacles and were often satisfied by numbers. It was not only Germans who found that viewpoint frustrating. At the asylum of Fains in Lorraine, Dr. Emile Renaudin conceded that “medico-administrative” statistics of “isolated” asylums were far from ideal for science. He called them, instead, tools of humanitarianism, “with which we can defend our budgets.” Since “no one is a prophet in his own land,” the alienist requires data for “the struggle against the prejudices of this proverb.” The advantage of numbers is to be accessible to everyone and to occupy the only terrain on which physicians can reach accord with “deliberating assemblies that are not animated by the sacred fire of philanthropy.”47 For Zeller, too, numbers were integral to campaigns of public outreach. He wielded them to show that problems of mental health were not confined to acutely affected individuals but would persist even if every insane person were placed in an institution. In an eight-year report for the years 1846 to 1854, he explained that while the revolutionary movements of 1848 and 1849 had “fantasies of the delusional at their head,” they also demonstrated what turbulence the “organ of soul” can withstand. Insanity participated in the great events of the day. “The whole life of man is involved in mental illness.”48

Thurnam’s investigation of insane heredity, with its focus on Yorkshire Quakers, was a local one. His push for standardization was cosmopolitan. Work with asylum data presented many problems and subtleties. Yet even the Anlage was employed as a discrete variable attributed to certain patients and not to others. Only occasionally did conceptual subtleties get in the way of counting, and the study of insane heredity, in Germany as in England and America, remained a matter of numbers.