CHAPTER 5

French Alienists Call Heredity Too Deep for Statistics While German Ones Build a Database, 1844-1866

There is one great cause of insanity, a primordial cause, the cause of causes, heredity, which fixes the disease in families and makes it transmissible from generation to generation.

—Ulysse Trélat (1856)

On these unconscious laws [of heredity] rests the secret of breeding and crossing in the realm of animals and plants, and the possibility of attending in a similar way to human society. Its necessity lies in our numbers. [Ihre Nothwendigkeit liegt in unseren Zahlen.]

—Wilhelm Jung (1866)

Asylums began using printed sheets and admission books to record information on new patients about 1820. At first they posed open-ended questions that invited discursive responses. By 1840, many relied on detailed forms to be filled in with nuggets of information, yet often still without specifying the field of acceptable answers. Before long, these pioneers of the information society were learning to suppress ambiguity by narrowing the alternatives.1 Previously, when asked the cause of a father’s or a wife’s insanity, people had told stories. Now they might be instructed to choose from a list before spelling out details. If heredity was involved, the doctors wanted to know which relatives had been affected and by what kind of physical or moral disorder. For about half a century beginning in the 1840s, such data offered hope for shaping a science of hereditary defect.

In 1846, Jules Baillarger, editor of the AMP, drew up a standard form for data entry designed to structure a collaborative program of hereditary research. His scientific goal was to measure the comparative hereditary influence of father and mother in determining patterns of mental illness in male and female offspring. This work inspired a shift away from the old, one-dimensional asylum tables, collected simply as part of the registration process, to a statistics that tried to pose scientific questions. The idea was to make the table into a tool for identifying and measuring relationships. Statistical tables emerged in these years as the characteristic data technology of their era, designed to make connections visible. Often, the key variable on these tables was heredity.

In France, Baillarger’s initiative failed. The ambition there to use empirical data to find patterns of human inheritance was never strong. The critical reaction was animated by a sense of biological heredity as immanent process bound up with forces of bodily development, too deep to be plumbed by mere statistics. French statistics of insanity, while plentiful, were focused mainly on administrative issues. Baillarger’s endeavor to gather statistics specifically for the purpose of a scientific study of heredity ran up against this barrier. A similar effort achieved better success in Germany as a program to measure statistically the import of biological sex for hereditary transmission. It was articulated most influentially by the alienist Wilhelm Jung based on more than three decades of data from the asylum at Leubus in the Prussian province of Silesia.

Yet the problems of making data useful never went away. Jung’s conclusions on sex and heredity were a bit miscellaneous and had no clear impact. What mattered most, including to Jung, was the hereditary reproduction of mental illness. It was, he declared, plainly evident in his numbers and made a compelling case for better breeding.

The Problems with Statistics

Statistics was central to the ambitions of the newly-founded AMP. Like their German peers, the French editors described their journal as a hub of integrated or collective investigation. Baillarger laid out the terms of this project in an unsigned introductory essay for its first number. Statistics, he declared, might advance on the basis of clear observations despite the protean character of mental alienation. In the second year of the journal, 1844, he published his own study of the inheritance of insanity, based on 600 observations, including 440 cases of direct heredity and 160 more involving siblings and collateral relatives.2 In medical writing, the word “observation” referred to a case or an episode of illness, which, especially for the insane, might be observed in multiple ways over a considerable period.3 He regarded the research as Herculean in its scale, a point his medical critics conceded. Yet he modestly declined to assert that any single study could be definitive. The prospects for mental medicine would be more favorable if a project like his could enlist a score of physician-researchers in different parts of France and beyond, laboring collaboratively to identify patterns of hereditary transmission.

To this end he created a tabular form, divided between paternal and maternal sides, each with columns for parent, grandfather and grandmother, uncles and aunts, great uncles and great aunts, male and female cousins, and brothers and sisters. The data form had rows for up to ten insane children in any family, a generous allotment. It included a blank space in the upper left on which a doctor choosing to participate could enter his name. Baillarger found, as he seems to have expected, that fathers transmitted insanity preferentially to their sons, mothers to their daughters. The maternal effect was the stronger, appearing in 271 cases, while paternal influence was limited to 182.4

On the basis of this work, Baillarger presented himself for a position in anatomy and physiology at the Paris Academy of Medicine.5 Although he was, in the end, elected, the assessment of his candidacy laid bare a French understanding of medical heredity as too deep or too innate to yield to empirical investigation, and thus far beyond the scope of statistics. The academy appointed a commission to assess his research, with the physician Hippolyte-Louis Royer-Collard as reporter. His report was printed in the academy’s Bulletin in 1847 then excerpted at length in German translation in the AZP. Royer-Collard, son of a doctor and nephew of an influential statesman and philosopher, professed a deep respect for Baillarger, which, if sincere, did not extend to his methods or conclusions. The inheritance of insanity, he declared, is really a question for philosophy, “I would also say, for administration; I mean, at least, for those men who occupy themselves seriously and disinterestedly with ways of improving the conditions of social life in civilized states.” The problem was not Baillarger’s observations but statistics itself, “from which men have tried, so improperly, to make a science.” An idolatrous cult, he complained, has grown up around the image of “what are called facts.” Too often, statistics has been described as the most positive and most certain of all methods of scientific investigation. He endorsed numbers as an administrative tool. Scientific truth, however, lies at depths that statistics cannot plumb.

FIGURE 5.1. This tabular form was designed to facilitate cooperative research on the importance of paternal versus maternal hereditary influence by making the data of different doctors interchangeable. There is a space in the upper-left corner to enter the name of the doctor. From Jules Baillarger, “Recherches statistiques,” 338.

Figures, for some men, even highly enlightened ones, are an irrefragable expression of truth. But . . . figures, like words, have only a representative value; statistics, which collects them and shows their direction is, by itself, but a blind woman [une aveugle] who does not reason: and, to get at the truth she promises, one must necessarily cut through all this drapery and go straight to the things represented, bypassing the signs that represent them.6

Royer-Collard bypassed mere statistics to divine a more essential truth of heredity lying at the crucial node of reproduction. The newborn is not merely produced by its father and mother but extends their existence, including their moral and intellectual faculties, into the succeeding generation. Triggering factors are of very little account. It is not the maladie, the illness, that is perpetuated, but the malade, the sick person, whose predispositions extend to health, constitution, and temperament. It is enough to grasp this principle to comprehend the crucial role of inheritance of insanity, occurring as an immanent process that could scarcely depend on empirical evidence.7

And that was fortunate, because Royer-Collard dismissed the evidence as utterly mendacious. He told how his father, the Charenton alienist Antoine-Athanase Royer-Collard, had accumulated information on causes for twenty years. For fifteen of those years he was assisted by Louis-Florentin Calmeil, his student, who subsequently confided to the son that the data was rubbish. Despite taking all possible care in his interviews with family members on the question of hereditary influences, Calmeil had discovered afterward that “eight times out of ten” they had deceived him. Every lie and every uncertainty had tended to understate the power of heredity, which must remain hidden when, for example, an early death prevents the expression of inherited mental illness. The blame for the faults in his report, Royer-Collard concluded, belonged not to Baillarger, but to statistics itself. Facts so complex as those of this living economy, double- and triple-sided facts, fused and entangled, cannot be added up as if they were independent units.8

Hard Facts and the Allure of Narrative

Ulysse Trélat found equally memorable reasons to reject testimonies on the causes of insanity, and with them, every kind of hereditary data. He had had a prominent role in public health during the revolutions of 1830 and 1848, then served during the Second Empire as a physician at La Salpêtrière, treating “a vast clientele of insane women,” whose lives he featured in an 1856 essay on the causes of insanity. He had learned to be wary of deceptive evidence, so readily conjured into mesmerizing narratives. His case stories exhibit this sweet seduction while proving his own masterful capacity to resist it.

He tells, for example, of a woman of “thirty years and some,” Madame J., who married while not yet thirty an active septuagenarian laborer. The dear husband is indispensable to his employer, and she thinks of nothing while he is at work but to keep up their little abode and await his return. One day, a young clockmaker, arriving to repair the pendulum movement, shocks her by declaring his love. She virtuously rejects these avowals, and he is polite and respectful when he brings back the clock, yet the flame in his eyes burns her soul. Tormented beyond her powers of endurance, she throws herself into the Seine then is rescued and sent to the asylum. “Assuredly we have here a sufficient explanation of the despair of this young woman. . . . Was there not in this little story enough misfortune, enough poetry to seize the entire soul?” Later, Trélat discovered that she had long suffered attacks of nerves, as had her sister. The cause of her madness was heredity, and the clockmaker with his long hair and black eyes achieved no more than to precipitate what would otherwise have developed later with a different provocation.

It was the same with a general’s widow who went mad after falling into destitution, and with an English working woman taken in by a scheming dentist who, promising marriage, used her resources to set up his practice and then abandoned her. Other cases that the doctors had explained in terms of physical causes such as childhood falls or blows to the head also gave up their secrets when he discovered a deranged family member.9

“We pass to observations that are still more striking”:

Lise R . . . was a young and very beautiful girl in the valley of Montmorency. A rich man, married, but of dissolute morals, noticed her, seduced her, and brought her into an utterly different world from that in which she had been raised. A simple life in the fields, of hard work during the day and deep sleep at night, gave way abruptly to excesses of the table, gambling, orgies, dances, spectacles, stays at the baths, journeys abroad. R . . . had from her seducer two beautiful girls, and these had scarcely begun to grow up when another household began taking shape amidst hers. R . . . and the new woman, who promptly became mother of a son, linked up and shared the same evenings of pleasure. One of the two little girls died. The children were raised in this disorder by the two concubines of the debauched old man, who still maintained his legal household in Paris, half a league from his harem.

But, after these joyous dissipations of every kind came the bad days. When you consume above your revenues, you devour the capital. They had to flee their creditors and transport the debris of lost luxury into an abode that was barely modest, living in shame, privation, and misery. Poor R . . . soon came into our asylum, where she remained the most beautiful, the most furious, and the most formidable of our patients. She was often visited there by the other lady, who would say to her child: “Come see Lise!” The girl had the same beauty as her mother. We didn’t see her for several years. What could become of her with such models?

For a long time we never looked for the causes of the insanity of Lise R . . . except in the life her seducer made for her. A complete change of life, pleasure, exhilaration, excess and exhaustion day and night, all the seductions and the satiety born of sumptuous habits of opulence, and then all at once suffering, tiredness, fears, quarrels and affronts engendered by ruin with no honorable recollections to redeem the abasement of such conditions: quite enough causes to trouble the soul and to shatter it. Well! All this wasn’t what distracted the reason of poor Lise. It is less poetic, but it is more truthful: she went mad because there were several insane in her family.10

Layered over these operatic tales, recounted with evident pleasure, there is always another story featuring a tough alienist who refuses to be taken in by their flimflam. The sinuous story line strikes a barrier and is completed, or annihilated, by facts and laws that are wholly external to it. Heredity arose here as an unyielding force, the irreducible continuity of life. Trélat had the steel to resist the tawdry allurements of surface explanations. “Error is attractive by nature, because it is always full of consolation and hope, while the truth, in most cases, is sad, inexorable.”11 The blows and misfortunes of life can be painful, but they cannot explain insanity. Those who keep looking will discover, behind the fog of appearances,

the true cause, the living cause, imperishable and transmissible. . . . The germ was there, and sooner or later it had to grow.

There is one great cause of insanity, a primordial cause, the cause of causes, heredity, which fixes the disease in families and makes it transmissible from generation to generation.

This is a law.12

Troubles with Tables: Some International Exchanges

The mood of Royer-Collard’s and Trélat’s hereditary doctrines was distinctively, if not quite uniquely, French. Carl Hohnbaum, Royer-Collard’s German translator, rejected his claim for hereditary continuity from parents to offspring. The propagator, he declared, must be distinct from the propagated. Although much concerned with causal mechanisms, he refused to allow that theoretical claims could ever supplant empirical investigation. Nature, retaining its creative power, brings forth mysteries but also reveals patterns, including great talents that run in families and hereditary sources for a range of diseases. Royer-Collard went too far in dismissing statistics, which should be combined with close study of particular cases. Without taking a position on Baillarger’s scheme to coordinate research with a printed form, Hohnbaum endorsed his effort to infer causal mechanisms from the statistics of medical experience.13

Royer-Collard’s critique of statistical research rested not only on his sense of the deep forces of heredity but also on an understanding of statistics as a bureaucratic endeavor, distinct from science. Morel’s career similarly exemplifies the possibility of treating heredity as an ineffable force while cultivating statistics for practical, administrative purposes. Baillarger, looking to statistics as a basis for science, dismissed asylum reports as hemmed in by their reliance on administrative categories. For the researcher taking an original approach to a serious question, the numbers from his own institution will rarely be sufficiently copious for reliable statistical conclusions. His solution was collective data, compiled and distributed by a well-managed journal. In this way, medical statistics of insanity could be freed from the inflexibility of institutional compilations.14

FIGURE 5.2. Asylum at Stéphansfeld (near Strasbourg). This lithograph from 1841 of the first asylum in Alsace shows a tranquil, rural site enclosed by walls. The institution was a key site of French statistics of insanity and, along with some nearby institutions, an important conduit for translation and data communication between French and German alienists. It remained so after 1871, when it was incorporated into the new German empire. From Renseignements sur l’asile départementale d’aliénés de Stephansfeld (Bas-Rhin) (Strasbourg: Vve Berger-Levrault, 1841), plate 1. In public domain.

This scheme of original research coordinated by a printed form does not seem to have gone anywhere. There was no getting around the separate institutions as principal loci of inquiry. Although Baillarger drew German supporters, in France he was caught between two poles. What seemed aimlessly empirical to philosophical authors like Royer-Collard was criticized by others as detaching statistics from the essential needs of state administration.

Emile Renaudin spent most of his career in Alsace, which functioned as a French-German borderland. His four-year report on the asylum of Stéphansfeld, near Strasbourg, printed in 1840, included an exemplary combination of administrative and medical data, including an exploration of heredity as predisposing cause of insanity.15 Five years later, he inserted into the AMP a multipart essay, really a book, on the administration of insane asylums. Here the focus was more narrowly practical. Beyond his duty to the state to operate an effective institution, he wrote, the asylum director needs to educate the public. He should print annually a “moral and administrative account” according to a uniform plan. This would be mainly a catalog of observations: patient data in the medical part and budget figures in the administrative. The state should collect these documents each year from all over France and publish them in May. They would provide a statistical basis for comprehending how insanity varies in relation to geography and to legal regimes. This sounds like the work of a census, but he preferred to rely on institutional records. They would require, however, to be reformed and standardized, which emerged here as his mission.16

Baillarger, who did not welcome a state publication competing with his Annales, responded with a critique of official statistics. To ward off this rival, he announced a new statistical yearbook, the Annuaire historique et statistique des établissements d’aliénés, to be published in April (!) as a number of the AMP. He does not appear ever to have acted on this intention. He pursued numerical uniformity by a different route, outlined in an open letter to Renaudin on the application of statistics to mental illness. Amariah Brigham promptly had Baillarger’s letter translated by “an Inmate of the New York Asylum” and published in the AJI. It begins: “Statistical researches have doubtless rendered great service to the study of mental diseases; but confined of late years in a circle consecrated by habit, they have ceased in my opinion to be so useful.” The true need was for collective work on a uniform basis by associations of physicians, who should fix in advance their research questions, such as the nature of inherited insanity.17

Brigham, it appears, was moved by Baillarger’s vision of uniform statistics to initiate his own series of articles on the statistics of insanity. While praising Baillarger, he seemed instead to follow Renaudin’s lead. Annual asylum reports provide the public with irreplaceable evidence of the curability of insanity, in this way encouraging legislators to fund these valuable institutions. Their principal defect was a lack of uniformity, and he held up the proposed English registers of 1842, modified from Thurnam’s proposal, as a proper basis for harmonized statistics in America. For his next installment, Brigham promised to answer objections to statistics. The series was, however, cut off by the sickness and death of this author.18

Renaudin, meanwhile, had answered Baillarger’s letter. The men agreed on the need for large-scale statistical research and agreed also on the desirability of standard forms and tables. But Baillarger had in mind a project of independent research designed to yield results of scientific interest for his journal. Renaudin, like Brigham, valued routine data collection according to rules set by the state. His praise for Baillarger’s “wise commentaries” served mainly to accent his doubts as to the value of Baillarger’s data. Statistics is no panacea, Renaudin wrote, least of all for science. Asylums require numbers, but mainly for rhetorical and administrative purposes. They can be understood by everyone; indeed, nobody listens to reasoning unless it is flanked by figures. Armed by data from his own and other institutions, he would challenge error and prejudice to win the battle for humane treatment of the mad.19

By 1848, Renaudin had begun reporting for the AMP on German institutions, which he now brought into the debate. Perhaps this reviewing heightened his sense of disparities of meaning among institutions for categories that, on the surface, appeared homogeneous. “Everywhere, and especially in Germany, the need is felt to unify and coordinate the numerous facts observed in asylums for the insane,” he wrote. The German AZP editors had just published a Normal-schema for asylum data, embodying scientific goals that he dismissed as worthless. It would contribute nothing, he declared, to knowledge of the causes and geographical history of insanity.20

The German report was preoccupied with statistics of heredity. It has the look of a compromise, an adaptation of Baillarger’s ideal to the shaping of scientific statistics for official reports. The editors were pushing an all-German project of compatible, if not yet collaborative, measurements, the data to be gathered up and diffused through publication in the AZP. Damerow, as editor, nurtured high hopes for this empirical undertaking, so different in spirit, he said, from the “dogmatic” psychiatry of the prior generation in Germany. He had just released an exuberant editorial introduction to his 1846 volume, vowing that statistics would now at last fulfill its promise to bring evidence to bear on the great questions of psychiatry. This, he let on, was to be achieved through a redesign of asylum and census reports.21

While Renaudin did not specify his objections, he could not have approved the ambition to set aside routine reporting and to redefine insanity, with its urgency for public health, as a scientific problem. Most of the sixteen tables proposed in Flemming’s schema involved converting raw numbers into ratios or percentages, sometimes in relation to a larger average of patients, sometimes as a fraction of the whole population. The latter would facilitate comparison across regional and national boundaries. These German alienists may have overreached, however. There are indications of discord. For some events, such as relapses, they were unable to specify any breakdown or typology, and on the crucial question of how to tabulate “etiological factors,” they came to a stalemate. The statistical problem of causation was thus to be left to the wise discretion of local alienists: “The correspondents will be allowed to compose a tabular overview according to their best insight and careful consideration of the respective causes.” This was scarcely a basis for standardization! At least they reached a consensus that hereditary predisposition (erbliche Anlage) should be a particular focus of attention.22 Heredity, in Germany, was the exception to midcentury doubts about data on causes. Baillarger’s work suited them nicely.

Methods of Tabular Statistics: Wilhelm Jung at Leubus

Paul August Wilhelm Jung followed Baillarger both in his commitment to statistical research on heredity, which stood above official routines, and in structuring his analysis according to the variable of sex. To Germans, at least, his two long papers in the AZP in 1864 and 1866 were a compelling model of what could be achieved with asylum data for research on inheritance of mental illness. They were regularly cited for half a century.

A range of German commentaries shaped Jung’s understanding of Baillarger’s work, in particular a close analysis of his text by Rudolf Leubuscher. Leubuscher had grown up in Breslau (Wrocław), a few miles from Leubus (Lubiąż), the source of his family name. The asylum at Leubus, converted from a Cistercian monastery after the Napoleonic wars, was where Jung, as assistant physician, gathered up thousands of patient observations. Leubuscher took his doctorate in Berlin with a thesis on religious mania and then served from 1845 to 1847 as Damerow’s assistant physician in Halle. His paper on inherited madness appeared in 1847 in the AZP and a year later in English translation. He subsequently made his reputation in Berlin as a public health reformer and ally of Rudolf Virchow.

Leubuscher emphasized the shaping of individuals by heredity, calling it “the best established and least doubtful” among the causes of mental illness. He acknowledged its obscurity as a medical concept, and even the inconsistency of measures of its effects. He had no truck with Royer-Collard’s theory of heredity as a continuation of the life of the parents. The instantaneous combination of maternal and paternal elements in the fertilized egg, a “middle thing” between father and mother, confers a type on the offspring, leaving no further role for the pregnant mother except to nourish her fetus. Mental dullness (Blödsinn), often congenital, seemed to him a more convincingly hereditary condition than insanity, which appears in adolescence or adulthood. He applauded Baillarger’s use of systematic data gathering to clarify the processes of insanity and to reconcile discrepant measures of its inheritance. On this basis, it might become possible to intervene effectively and to reduce mental illness through better practices of breeding and child-rearing.23

![F 5.3. Asylum at Leubus, formerly a Cistercian abbey. A visitor wrote in 1852: “The building, which is of vast size, had originally been erected as a palace, was afterwards used as a convent, and finally, in 1830, converted to a lunatic asylum” (W. F. Cumming, [London: John Churchill, 1852], 45). Most early German asylums were converted religious buildings. In public domain.](images/05-03_porter_Fig_Psychiatry_Lubiaz.jpg)

FIGURE 5.3. Asylum at Leubus, formerly a Cistercian abbey. A visitor wrote in 1852: “The building, which is of vast size, had originally been erected as a palace, was afterwards used as a convent, and finally, in 1830, converted to a lunatic asylum” (W. F. Cumming, Lunatic Asylums in German and Other Parts of Europe [London: John Churchill, 1852], 45). Most early German asylums were converted religious buildings. In public domain.

The faith of German alienists in statistics was at a high in the 1840s. Wilhelm Griesinger, leader of a Berlin group, explained in his 1845 textbook of mental illness how multiple causes create complex variability both within and among institutions.24 Flemming echoed the thought in 1852, concluding that averages alone could stabilize this Proteus.25 In 1854, the physiologist Georg Schweig discussed three possible ways to apply mathematics to insanity and concluded in favor of the simplest, the method of classification into groups, requiring only that the groups be mutually exclusive. Physicians too often neglected this rule, he continued, citing the wildly discrepant causes in Esquirol’s tables. A proper statistical categorization would distinguish heredity without other causes from heredity with other causes and from other causes without heredity. Such reasoning privileged the causal import of heredity. It also called attention, as Jung later would, to interactions of disparate causes.26

The institution at Leubus had been founded about 1830 by the physician Moritz Martini, who remained as director until Jung replaced him in 1873. On the basis of a census of the insane, and supposing the continuation of high initial cure rates for fresh patients, Martini had reckoned that one hundred beds would suffice to care for the local population.27 The first report in 1832 did not take up causes. But he must have collected causal data from the beginning, because Jung’s essay on the inheritance of mental disturbance, appearing in 1864, five years after his arrival at Leubus, included the results of thirty-three years. From discussions and abstracts of Leubus reports in the AZP, it appears that German alienists esteemed them as among the very best of the genre. The tables for this institution, appearing every few years, were always accompanied by results of a census of insanity in the province of Silesia. Heinrich Laehr described the four-year Leubus report for 1860 as excellent. Other provinces now prepared similar reports, he remarked in 1865, but none as yet had quite matched Leubus. It would be desirable to print up reports like these in enough copies to distribute to all readers of the journal.28

Jung’s paper became a model for the next generation of asylum studies of heredity. Its scope was monumental: 3,606 patients filling 130 pages, or 177 if we include the 1866 continuation. German research on psychiatric heredity, as on so many topics, was now very serious. Jung made no effort to probe bodily mechanisms of hereditary transmission. This was a data project, focused on family relationships among those diagnosed as mentally ill. “The task of this work is to be purely statistical, and it should therefore hold at a distance all Raisonnements, with their openness to ad hoc considerations.” He would “leave it to the naked facts alone to speak and from them to draw naked conclusions.”29 Jung gave no ground to those troubled souls who insisted on interpretation to ascend to sound conclusions, quantitative or not. This meant ignoring subtle issues of temperament and its diverse tendencies, since these would lead to speculative and inductive conclusions rather than statistical ones. His tables relied strictly on diagnosed mental disorders.

But subtle reasoning, barred at the door, came in through the window. The detection of patterns of inheritance depended on satisfactory descriptions of the phenomena of insanity, and these, he had to concede, were far from transparent. He supposed that physical damage or organic disease could lead to mental disturbance and that such cases could become hereditary. It would be valuable to identify the circumstances under which an Anlage goes dormant in the direct line while popping up among collateral relatives. What is transmitted from parent to offspring, he reasoned, cannot be the disease itself but rather a bodily order, form, or condition, an “organic Anlage.” Martini spoke in those years of “the inherited Anlage, the transmitted seed.” Often what really matters for disease, wrote Jung, is the “material substratum,” which can be stimulated to develop by any kind of “accidental impulse,” whether internal or external.30 It begins to sound like Raisonnements. Jung struggled to comprehend not just transmission as such, but how it interacted with other factors recorded at the time of admission, including age, sex, disease form, and the delay from disease onset to treatment. He hoped to determine how results of treatment depended on these factors, alone and in combination. He acknowledged that much about insanity, even the demarcation of sickness from health, was clouded by ambiguity. In many patients the illness evolved over time, even to the point of requiring a revised diagnosis. This kind of information could not just be transcribed unthinkingly from the medical reports that served as his sources.31

Above all, he sought out variables that determined the probability of hereditary transmission, and with them, a better measure of the percentage of mental illness attributable to heredity. Like many writers on causes of insanity, he believed that the role of family Anlage was almost always underestimated. In the public section of his hospital, filled with paupers, many knew almost nothing of relatives beyond their own parents. The paying patients, though better informed of their lineages, tried to conceal evidence of family disease. Sometimes, what the families hid might be learned from reports of the recommending physicians, who also could provide information about the medical condition of these relatives. Many families, unfortunately, were so dispersed that nothing could be learned about them. Still, the institution at Leubus held more than thirty years of records. It is pertinent that German institutions in this period kept their patient records in files rather than the unwieldy case books used by British and American asylums. From the scale of Jung’s investigation, it is evident that Dr. Martini was willing to dedicate quite a lot of the time of his third physician to this investigation of insane heredity. Martini, indeed, had initiated the study and had printed results in 1860 for the first thirty years of the institution. He was keenly interested in the force of heredity and how it differed by religion as well as sex. In one report, Protestant insanity proved to be hereditary in 20% of cases, Catholic in 17%, and Jewish in 35%.32

Jung gave much thought to the problem of organizing data and appears proud of his solution: the compilation of lists. Hereditary patients were to be categorized by their relationship to another sick person, such as mother to daughter or uncle to nephew. Like Baillarger, he carefully distinguished the paternal from the maternal side. Vague references in the records—for example, to a family Anlage or a mentally ill grandfather—required another set of more provisional lists. Some persons would appear twice, both as sources and as recipients of hereditary influence, a duplication that required numerical correction to avoid double-counting.

Jung was as systematic as possible, using a hierarchy of letters and numbers to sort out heredity by sex and by nearness of relationship. It is all a bit numbing. Letters distinguished male from female patients; roman numerals indicated inheritance on father’s side, mother’s side, both sides, or between siblings; arabic numerals distinguished insanity of a parent from other relatives. He proceeded to a still finer categorization. For example, “A.I.1” designated insane men whose nearest affected ancestor was the father. There were 48 such patients, in 17 of whom the Anlage was reinforced by at least one additional sick relative, and of these, 11 belonged to families with only a single form of illness. After splitting his cases as far as possible, he descended to the level of individuals. Of the male patients with an intensified Anlage whose fathers suffered the same form of illness, there was one case of melancholia in which the paternal grandfather and brother of the patient also suffered melancholia, two cases of melancholia in which just the paternal grandmother also had melancholia, and so on. Jung continued in this vein for about thirty pages. The family characteristics extended beyond diagnosable mental illness to include drunkenness, apoplexy, epi.tify, and singularities or unusual behavior. Would Jung have been shocked to be told that he was compiling a database? Like Baillarger, he wanted his technique of disciplined data entry to permit any researcher to add or recombine, to compare and even (granted a few simplifying assumptions) measure the strength of hereditary effects.33

FIGURE 5.4. Wilhelm Jung offered this tabular scheme as a compact and precise way to record data on hereditary transmission and to facilitate analysis. On the horizontal axis, he used A for male and B for female insane. I indicates mentally ill relatives on the father’s side, II on the mother’s, III if on both sides, IV for siblings. On the vertical axis, he used 1 if the affected relative was a parent, and 2 if it was some other relative. The table continues down the page with finer distinctions and percentages. From Jung, “Untersuchungen,” 622.

Jung’s conclusions, as in so many asylum reports, lead us back into the world of naked, unexplained, and, for this reason, strikingly miscellaneous facts. Insanity breaks out mainly with the onset of adulthood, affects Protestants more than Catholics, and is more frequent yet more easily cured for women. Cases within a family group are often similar. Women have a stronger Anlage for inherited mental disturbance than men. Martini’s result on differential inheritance by religion, however, he brushed aside as an artifact: it is merely that the most inbred (and hence degenerate) groups are the best informed about their kin. Jung’s data confirmed the familiar result that hereditary insanity was more curable than nonhereditary, but they surprised him by suggesting that inherited insanity had the best outcomes when the affected ancestor suffered mental illness rather than a less severe condition such as epi.tify, hysteria, or peculiarities of character.34

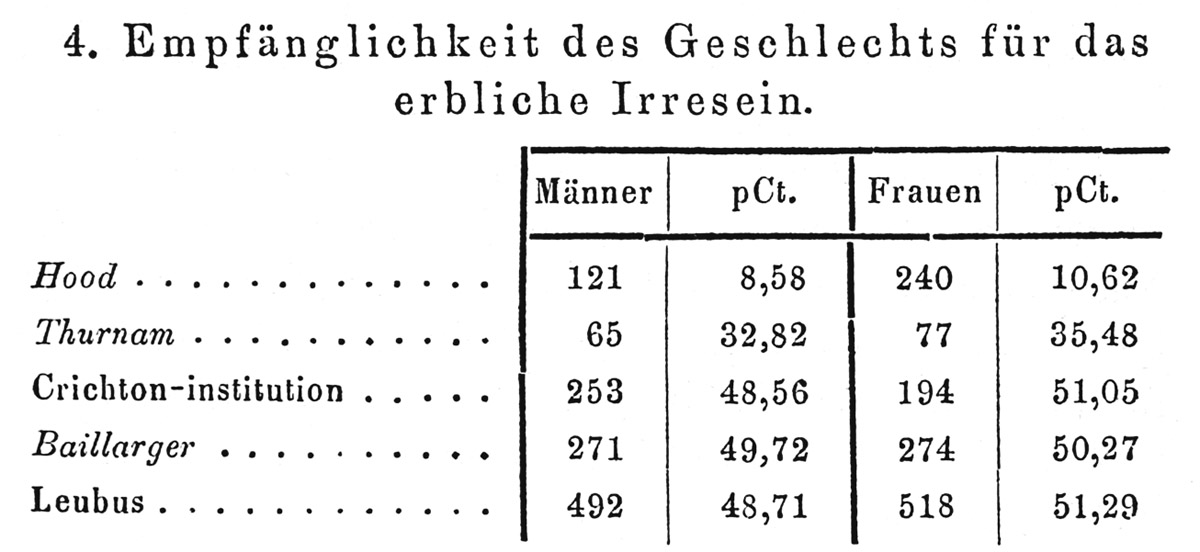

Soon after publishing his study, Jung was drawn back to this topic by a closely related paper from Scotland. Since he lacked access to the Journal of Mental Science, he consulted the French translation, which was published within months in the AMP. The author, Hugh Grainger Stewart, had compiled a report based on hereditary data from twenty-five years of experience at the Crichton Royal Institution, where he served as medical assistant. These records, Stewart explained, had been kept by three successive physicians and relied on information from friends and medical advisors of the patients. The questions posed to them were extremely loose: “Is the patient, or his relatives, subject to any hereditary, nervous, or periodical disease, and what? Or have they manifested any peculiarity, eccentricity, or prominent propensity, or tendency to crime?” Jung was especially interested in results concerning hereditary influence as a function of sex.35 Stewart’s findings were in good accord with his own results, and with many others: a solid, repeatable finding of asylum-based statistical research. He was moved to what we can call meta-analysis, based on a meta-table. Even though the absolute measures varied greatly, from Charles Hood’s 8.58% and 10.62% at Bethlem to figures around 49% and 51% in Scotland, Paris, and Silesia, the differences, however slight, were all in the same direction, all showing greater female “receptivity” to hereditary madness.36

FIGURE 5.5. Table of male and female “receptivity” to hereditary influence, as measured in five studies in different institutions. Jung stressed that while the differences of receptivity between the sexes were small, all pointed in the same direction. The comparative roles of male and female in hereditary transmission were of great interest to asylum researchers. From Jung, “Noch einige Untersuchungen,” 220.

For decades, beginning in the 1840s, the breakdown of hereditary results according to sex appeared the most promising way to get beyond mere numerical summaries to some kind of insight into mechanisms of heredity. By 1865, the range of numerical conclusions on inherited insanity was expanding. Another such study, a twenty-year report, appeared in 1866 from the noted institution at Illenau in Baden, directed by Christian Friedrich Wilhelm Roller, third in the triumvirate of editors of the AZP. He charged his younger brother Robert to prepare the statistics, which he then mobilized to shed light on causes and on the effectiveness of treatment.37 The Illenau weekly newsletter, written for personnel at the asylum and perhaps for higher officials, commented on the cheering conclusion of these statistics: that patients with a hereditary Anlage are not thereby condemned to confinement until death but are actually more likely to recover. Less encouragingly, Roller appealed to an “inner conviction” of alienists that the increase of insanity was no statistical illusion but a genuine consequence of excessive demands on the modern brain, stormy politics, extremes of urban wealth and poverty, and the dangerous use of stimulants.38 Like Jung, the Rollers relied where possible on a cutting-edge technology of data analysis, the correlation table. They were particularly interested in co-related variables, including disease form and percentage of cures; assigned cause and disease form; and cause and percentage cured. They vowed to avoid “excessive subjectivity” and “to strive for all possible objectivity.”39

Damerow also weighed in at almost the same time with a twenty-year report on the Halle asylum. He focused less on tabular technologies than on a troubling rise in the percentage of hereditary patients. Through marriages of relatives, it seemed, unnoticed personal Anlagen were infecting whole families. It was, he said, like the statistics of suicide and crime in a well-known book on statistical laws by the economist Adolph Wagner, an accumulation of separate causes from which emerged a disconcerting pattern of regularity. Wagner, the son and grandson of doctors, helped set off a German debate on free will by advertising the uncanny statistical stability of suicide, a central concern of alienists. Damerow, who knew Wagner’s family, looked for an explanation in patterns of heredity.40

Selective Breeding as Social Medicine

By 1865, the statistical investigation of causes was entering a new phase. Jung, too, set out on the path of the correlation table. It took a lot more work to process figures in this way, all the more so when thousands of cases were involved. The asylum doctors were moving into an era of arduous data management.41

Jung’s willingness to make this effort reflected his firm conviction of the importance, practical as well as theoretical, of hereditary causation of insanity. Dismayed by English historian Henry Thomas Buckle’s disregard of the power of heredity, he appealed to Trélat’s pronouncement that heredity was “the cause of causes.” “Heredity has an essential role in the genesis of mental illness,” especially in the case of marriages between branches of the same family. Mental weakness arises in the spoiled marriage bed. Weakness and disease are not only inherited by children and grandchildren but can “leap over whole generations, ‘remaining there hidden within and in this hidden form be transmitted again.’ ” This concluding phrase Jung copied from Dr. Friedrich Rolle, an early German expositor of Darwin’s theory with a particular interest in biological inheritance. The biology reinforced hereditary concerns that alienists had been discussing for decades. Damerow too was now crediting Darwin as having shown how propagation of weak and inferior types leads in biology to species ruin. For humans, this applies most urgently to hereditary forms of psychical illness. Jung, following Rolle and suspending his ideal of naked, unexplained facts, posited hereditary elements, borne by the cells and susceptible to environmental influence, that could act as a tendency or receptivity.42

Again we are converging on eugenics. Jung concluded that “unconscious laws” of heredity explain “the secret of breeding and crossing in the realm of animals and plants and the possibility of attending in a similar way to human society. Its necessity lies in our numbers. If these are convincing, there will be no need for prohibitions, no external coercion.” Jung quoted here the words of another medical Darwinian, Hermann Eberhard Richter, who had caught a vision of Zukunfts-Medicin, or “medicine of the future,” and pointed to a new and higher duty, “to lighten the burden of the struggle for existence” and to promote the “improvement of human capacities through rational breeding.” The advisability of controlling the reproduction of persons of defective heredity seemed clear. The “rational necessity” of Jung’s numbers might permit breeding decisions to remain voluntary. He added the happy thought that medicine was now on the path to “calculating in advance the success or failure of any marital bond,” and the darker one of looming “degeneration and the most frightful proletariat.”43