The Eastern and Western armies were virtually identical in make-up. Those commanders too young to have been veterans of the civil war of the last half of the 16th century were veterans of Hideyoshi’s Korean conflict. Both armies were well-trained, well-equipped and well-disciplined.

There was little in the way of ‘rank’ as we understand it in modern military usage. Those daimyô who commanded their own clansmen are usually referred to in English as generals; so a general might command anything from 500 troops to several thousand. Beneath the daimyô were direct vassals and trusted family retainers as officers. In the case of the Tokugawa, several great generals under Ieyasu’s command were also heads of their own clans (the Honda, Hosokawa, Ii and others), which made them generals under a general – a familiar Western concept. Still, one could refer to Hosokawa, for example, as ‘one of Ieyasu’s captains’.

Officers commanded and led from horseback. This statue of one of the Toda lords of Ogaki Castle, in the castle grounds, is typical of the mounted warrior of the end of the 16th century. Toda Kazuaki (1542-1604) fought for Ieyasu, and in 1634 his son was invested as lord of what had been Ishida Mitsunari’s personal castle. It was a mark of great favour.

| Tokugawa Ieyasu | 30,000 |

| Honda Tadakatsu | 500 |

| Hosokawa Tadaoki | 5000 |

| Ii Naomasa | 3600 |

| Matsudaira Tadayoshi | 3000 |

| Tsutsui Sadatsugu | 2850 |

| Arima Toyouji | 900 |

| Asano Yukinaga | 6510 |

| Fukushima Masanori | 6000 |

| Ikeda Terumasa | 4560 |

| Ikoma Kazumasa | 1830 |

| Kanamori Nagachika | 1140 |

| Katô Yoshiaki | 3000 |

| Kuroda Nagamasa | 5400 |

| Kyôgoku Takatomo | 3000 |

| Oda Yûraku | 450 |

| Tanaka Yoshimasa | 3000 |

| Terazawa Hirotaka | 2400 |

| Tôdô Takatora | 2490 |

| Yamanouichi Kazutoyo | 2058 |

| Yoshida Shigekatsu | 1200 |

| Total | 88,888 |

Due to the feudal make-up of the armies, nothing corresponding to a conventional corps, brigade or regiment existed. Greater lords had lesser lords under them, and so on. Well over 100,000 men who were not at Sekigahara itself were also ‘involved’ in the campaigns in Mino and neighboring provinces. They were held up in castle seiges or maintaining strongholds elsewhere. The following orders of battle represents the major commanders of both sides who were at the battle itself on 21 October, 1600. The numbers are not entirely certain, but they are agreed upon by most authorities. Modern scholars put the total number of men in the field that day at between 170,000 and 200,000.

| MÔRI TERUMOTO* | – |

| Ishida Mitsunari | 4000 |

| Shima Sakon | (1000) |

| Gamo Bitchû | (1000) |

| Akaza Naoyasu † | 600 |

| Chôsokabe Morichika | 6600 |

| Kikkawa Hiroie † | 3000 |

| Môri Hidemoto | 15,000 |

| Ankokuji Ekei | 1800 |

| Kobayakawa Hideaki † | 15,600 |

| Konishi Yukinaga | 4000 |

| Kuchiki Mototsuna † | 600 |

| Natsuka Masaie | 1500 |

| Ogawa Suketada † | 2100 |

| Ôtani Yoshitsugu | 600 |

| Ôtani Yoshikatsu & Kinoshita Yorichika | 3500 |

| Shimazu Yoshihiro | 1500 |

| Shimazu Toyohisa | (750) |

| Toda Shigemasa & Hiratsuka Tamehiro | 1500 |

| Toyotomi retainers | 2000 |

| Ukita Hideie †† | 17,000 |

| Wakizaka Yasuharo †† | 990 |

| Total | 81,890 |

* Not present, in nominal command, but based in Ôsaka Castle.

† Traitors to the Western cause.

†† Nominally second-in-command.

Notes: numbers in parentheses indicate the size of a sub-command taken from the commander’s unit, the full force of which appears above.

This mix of rank and position, and the varying size of troop contingents make it difficult to create an order of battle as it is commonly understood. The usual modern distinctions of corps, division, brigade, regiment, and so on, are completely out of place. Each clan or functioning body may be considered a division, and the larger sub-units may be considered brigades, but there is no direct correlation.

The relationship between vassals or allies and their single overall commander was similar to the combined allied armies of the Second World War; there were both internal chains of command and overall external unifying chains of command.

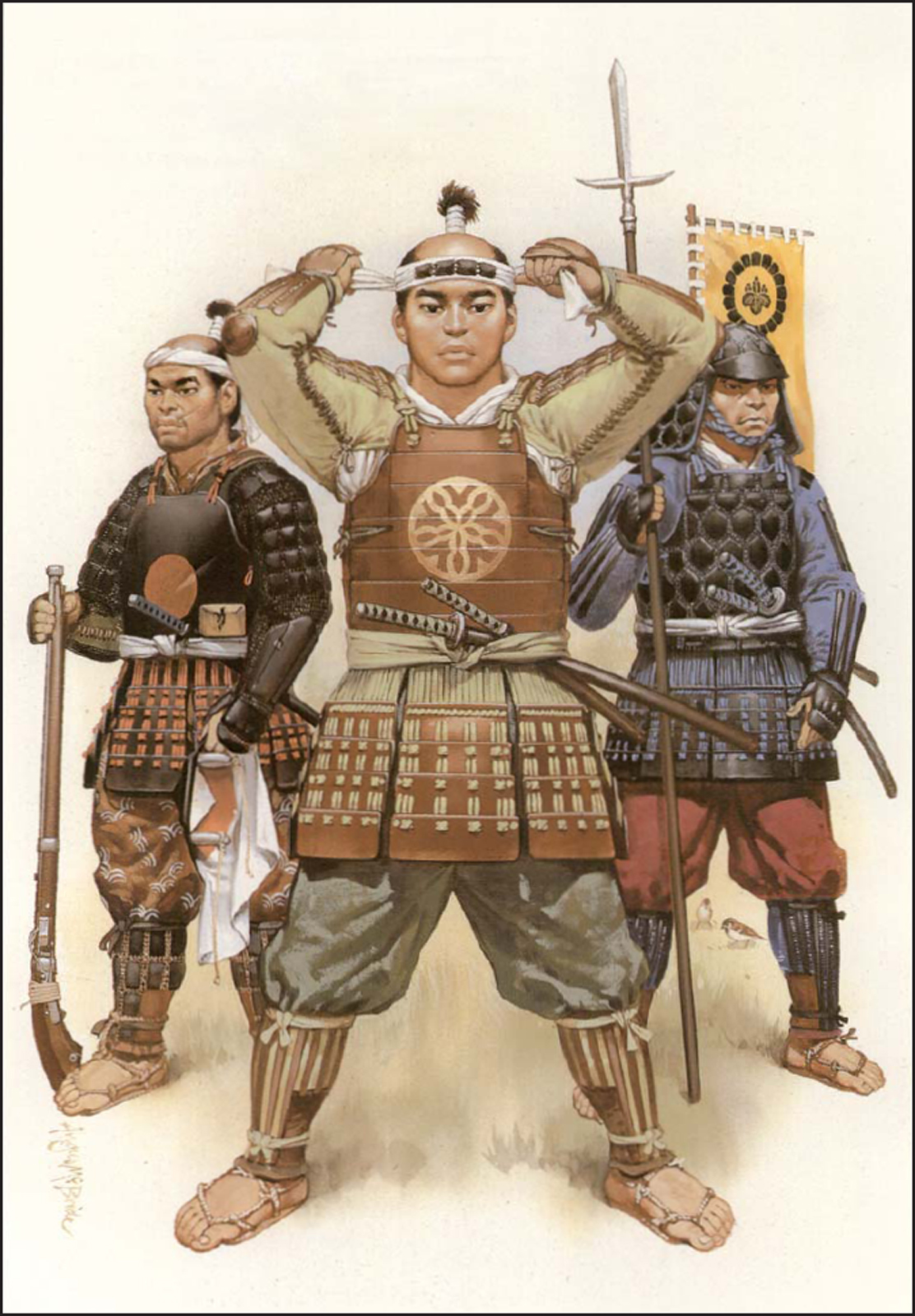

These three warriors represent the Ashigaru, the lions share of both armies. Their armour and weapons were inexpensive and simple. The man on the left wears a simple belly-plate, the one in the middle a one-size-fits-all variation of the standard okegawa do, and the man on the right a folding armour of hexagonal plates.

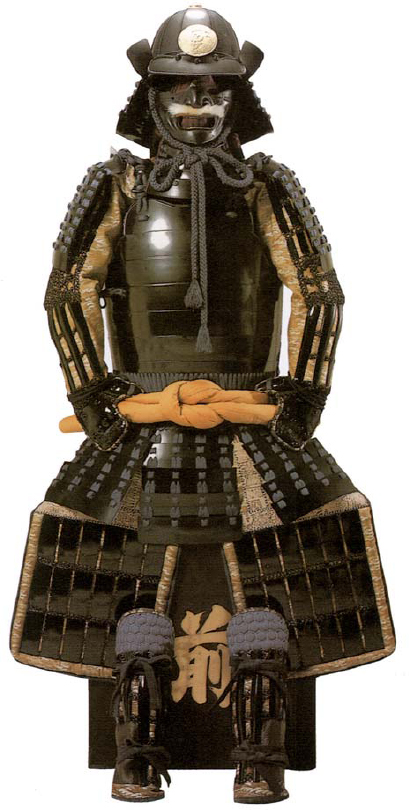

The average warrior in the field probably wore a simple but complete armour such as this. The solidly riveted cuirass, called an okegawa dô, could even be made shot-proof. (Yoroi no Kôzan-dô)

On many occasions this nebulous organisation, combined with the egos of the generals, nearly led to disaster; occasionally it did so, when the generals refused to follow the orders of a commanding general. For example, during the Sekigahara campaign, the Eastern Army (the Tokugawa faction) was attacking the Western stronghold of Gifu Castle. Two of the attacking generals, Ikeda Terumasa and Fukushima Masanori, argued over who would attack the castle first, and finally challenged each other to a duel over the issue. Fortunately cooler heads suggested that one should attack the front and the other attack the rear.

This highlights a problem the Japanese armies had during this period. No matter how well laid, plans were at the disposal of those with more interest in personal reputation and honour than overall outcome. It is easy to say that they were just being short-sighted, but incidents like this occurred in Korea as well. In fact, one can legitimately wonder what they might have accomplished on the continent if there had been less ill-will and more co-operation among the various commanders. Perhaps it is because Ieyasu, a far-sighted strategist, saw this as a problem that he moved as slowly as he did; he wanted to be sure that his orders would be followed and things go according to plan.

Under the commanders, discipline was severe and swift. Everyone had a rôle and knew what is was; everyone had a place and knew it. Failure could mean being stripped of rank, banished or even killed.

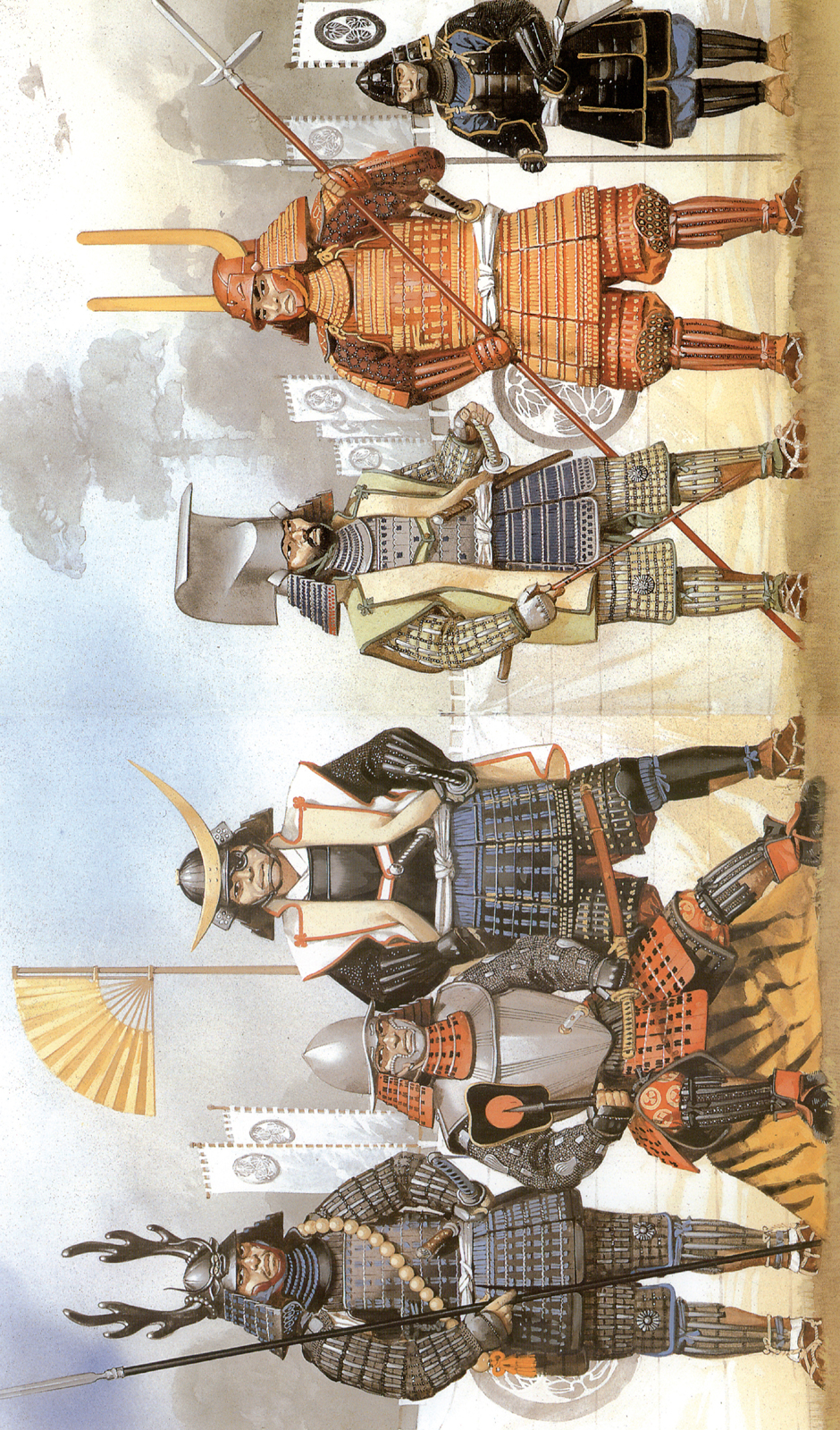

Some daimyô provided uniform armours for their troops, to boost morale and aid recognition –as with Ii Naomasa’s famous ‘Red Devils’. Another daimyô famous for his uniform was Date Masamune, who equipped his entire army – from the lowest troops to the commanders – with four-sided solid armours called yukinoshita dô, with only the fittings and details marking any difference in rank.

Other daimyô handed out whatever they had available; others provided a stipend to allow their troops to buy gear they wanted. Many troops supplemented their armour allowance with the time-honoured tradition of looting the dead, acquiring a better helmet, weapon, or suit of armour from the fallen enemy. Although often officially discouraged, it was far from uncommon.

The ashigaru, the low-ranked men that made up the bulk of the army, usually got the least expensive equipment. Their body armour was often a suit of small plates held together by mail and designed to fold away into a small package, called tatami gusoku (folding armour); a simple cuirass of solidly riveted steel lames, called an okegawa dô; or a hara-ate (armour that protected the front but not the back).

Armour for the average soldier consisted of a dô (cuirass), and some form of kabuto (helmet). In addition, they had kote, which were padded sleeves with integral splints of lacquered metal and mail sewn on. Most had some kind of leg armour, even if it was only splinted shin defences called suneate. A split-apron like piece of armour (called haidate), designed to protect the thighs, was often worn; the latter were uncomfortable on the march, but those who were issued them usually took advantage of the protection they offered, even if only on the field.

The variety of armour and different methods of decorating it at the close of the 16th century was incredible. Even something as simple as a cuirass of horizontal lames solidly riveted one to the other might have flush rivets, domed rivets or even large decorative fasteners; it could also have one of a dozen different ‘lines’ of cut (straight lines, saw-toothed edges, deep rolling curves, arrow-head shaped cut-outs and so on).

One of the most striking features of Japanese armour of the period was the sashimono, a long banner worn from a crossbar and pole arrangement attached to the back of the armour. These banners were marked with the mon, or crest, of the commander of the samurai’s unit. Naturally, Lords didn’t usually wear sashimono; they had standards and standard-bearers. The banners of different units within an army could be similar, to provide instant recognition. (In Akira Kurosawa’s films Ran and Kagemusha, these banners are in evidence in all battle scenes; in reality there would have been thousands.)

Their primary weapons were long lances called yari, which were even used by cavalry. In English they are often called spears, but this gives the mistaken impression that they were missile weapons; in fact they were never thrown. Most yari were around nine feet long, although many clans were uniformly equipped with longer or shorter ones.

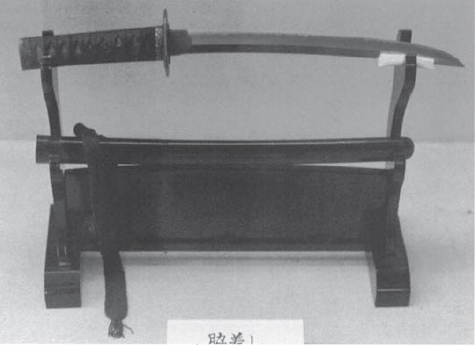

The wakizashi was the companion sword to the longer, deadly katana or tachi. The blade was anywhere from a foot to two feet in length. Contrary to popular modern opinion, it was not reserved for committing suicide. (Gifu Castle)

A page sits on the floor next to a stand for matchlocks. In castles, some lords had their guns on display in the same manner as their swords. Note the variety in ornamentation and size. The page wears an outfit called a kamishimo, which was the standard day-to-day wear of most samurai at this period. (Kiyosu castle)

Tokugawa Ieyasu is supposed to have worn a European armour at the battle. Several suits of Spanish or Portuguese make had been given by foreign potentates as gifts to curry the favor of powerful lords. Invariably they were altered to suit Japanese taste. To his right stands Honda Tadatsugu one of Ieyasu’s most loyal retainers and one of the Eastern Army’s commanders at Sekigahara. To his left stands ‘The One-Eyed Dragon’, Date Masamune, another loyal Tokugawa vassal. At the time of Sekigahara Masamune was engaged in a campaign against Uesugi Kagekatsu and his vassals in northern Honshu.

Kuroda Nagamasa here wears a jinbaori, or camp coat, over his armour. Generals wore them in camp, seldom in the field. Considering the chaos at Sekigahara, some generals possibly wore theirs all day, in and out of camp. Accompanying him is Ii Naomasa whose ‘Red Devils’ launched the charge which opened the battle. The banner of the samurai with them shows him to be of the Tokugawa clan.

A daimyô would have worn an armour such as this. It is of solid lames cut and punched to imitate scale construction, and fully laced. (Yoroi no Kôzan-dô)

The secondary weapons were swords, which they carried in pairs: a long sword called a tachi or katana, and a smaller sword called a wakizashi. Some carried dirks as well. The poorest soldiers carried at least the longer sword, with a dirk or two in reserve.

The dirk was generally used to remove the heads of the slain enemy as a battle trophy. At the end of the day, heads would be counted, and those of important people (daimyô and generals, say) would be presented to the commander for a head-viewing ceremony.

Virtually every clan in both the Eastern and Western armies had units of dozens or even hundreds of arquebusiers called teppô tai. The weapon had been introduced from Portugal, by accident, in 1542 and by 1600 was being made domestically in huge quantities. It had changed the face of Japanese warfare. No longer was posturing, making speeches, and single combat the overriding method of warfare; now the lowliest footsoldier could instantly slay the mightiest lord from a great distance.

The arquebusier units had largely supplanted the units of archers common in battles only a few decades before. Bows were still in use, but their importance was greatly diminished. When the loyalist Shimazu clan arrived at Sekigahara with their archers, and with old Shimazu Yoshihiro himself carrying a bow, the rest of the army viewed it as rather quaint.