The one-day battle of Sekigahara was not an isolated conflict; it was part of a true campaign. The struggle that culminated in the narrow valley around the village of Sekigahara on 21 October 1600 had actually begun in earnest in July of that year.

The yarô-kabuto (‘bumpkin helmet’) was designed to represent the head of a peasant, with closely cropped hair. It was another of the uncommon helmet forms that appeared during the latter years of the 16th century. Like most, it was built up on the base of a three-plate zûnari. (Yoroi no Kôzan-dô)

Uesugi Kagekatsu was involved in building up his domain’s defences when Ieyasu sent word to Aizu from Ôsaka in May asking him to explain his actions. The reply came not directly from Kagekatsu but from his chief counsellor, a man named Naoe Kanetsugu, who responded with sarcasm, saying that while citified samurai spent their time collecting tea implements, country samurai collected weapons.

Echigo, the neighbouring province to Aizu, had as its lord Hori Hideharu. He too was alarmed at the actions of Kagekatsu. The belligerent lord of Aizu had 80,000 men working round the clock building a new castle and several defensive points around it. He was also building roads that could be used to move large numbers of troops.

Kagekatsu went so far as to make an attempt on the life of one of Ieyasu’s messengers, a man Kagekatsu’s advisors (perhaps accurately) took for a spy. Ieyasu, incensed at this affront to his authority, sent for Kagekatsu, ordering him to come personally to Ôsaka to explain his actions. When no satisfactory reply was forthcoming, Ieyasu decided that his only option was to call for the coalition to put the Uesugi down, so on 12 July he held a war council in Ôsaka to plan a campaign against Aizu with his generals. On 22 July his chief allies in the outlying regions left Osaka for their home provinces to prepare for war. If not against the Uesugi specifically, Ieyasu knew that he would need to have people in every part of the country to keep things under control when hostilities broke out with Mitsunari.

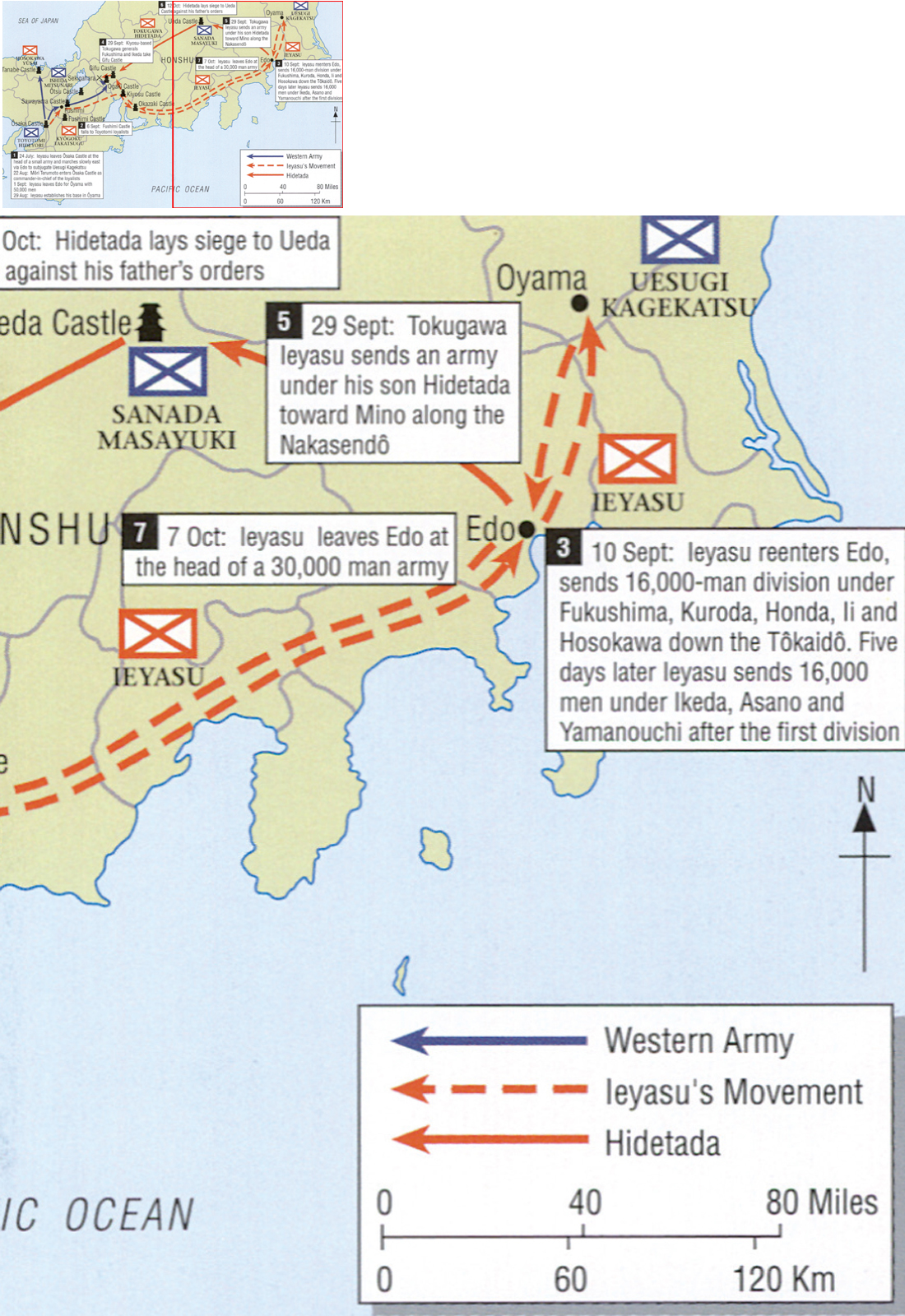

Ieyasu gathered his army, and on 24 July, to Mitsunari’s secret glee, began a leisurely march eastwards from Ôsaka Castle.

For his part, Kagekatsu was not concerned, as he was certain that before he was in any real danger Mitsunari would be sweeping up behind Ieyasu. When Kagekatsu struck, a few weeks later, Tokugawa allies Môgami Yoshiakira and Date Masamune immediately counter-attacked. Maeda Toshinaga would have joined as well, but he was suddenly preoccupied with a war against his brother and others who supported the loyalists. A fourth daimyô, Satake Yoshinobu, refused to take arms against Kagekatsu, but with the forces of the Môri and Date, the situation was under control.

Fushimi Castle, once Hideyoshi’s residence, had become Ieyasu’s. The latter would trade it for Ôsaka Castle after the death of Maeda Toshiie. It was one of the first targets of Western aggression once hostilities were declared. The siege resulted in the death of its garrison commander, an old friend of Ieyasu’s named Torii Mototada. One of the Western generals taking part in the attack was Kobayakawa Hideaki. He would later apologise to Ieyasu, and be forgiven, for his part in the conflict. A modern reconstruction.

Ieyasu stopped for the night in Fushimi Castle on 25 July, spending the evening talking and drinking with the castle garrison commander, an old and trusted friend named Torii Mototada. Both knew that once hostilities began in earnest, Fushimi would be one of Mitsunari’s first targets, and that there was no way Mototada would be able to hold it. The castle would fall and he would die, and both he and Ieyasu knew it. Their parting the next morning became a popular subject for artists for generations, so emotional was it for both of them.

Ishida Mitsunari called a war council even as Ieyasu was marching eastwards from Osaka. On 17 August the chief conspirators met in Mitsunari’s castle of Sawayama. Ukita Hideie was Mitsunari’s deputy, and among those in attendance were old Shimazu Yoshihiro (then 65 year old – practically ancient for a daimyô), lord of Satsuma; Kobayakawa Hideaki; Nabeshima Katsushige, son of Nabeshima Naoshige, lord of Saga; Chôsokabe Morichika, lord of Tosa; and Ôtani Yoshitsugu, lord of Tsuruga. The latter had in fact been on his way to join Ieyasu in his campaign against Uesugi Kagekatsu, but Mitsunari had intercepted him and convinced him to join with the loyalists instead. It was a decision Yoshitsugu would regret for the rest of his life.

Ieyasu advanced slowly, which enabled him to monitor Mitsunari’s machinations. He had full confidence in Masamune and Yoshiakira’s ability to contain Kagekatsu. For his part, Mitsunari was certain that Ieyasu would engage the Uesugi before long, and then Mitsunari could move his army up the Nakasendô and Tôkaidô (the two trunk roads between Edo and the capital) and fall upon him from the rear.

Ieyasu reached Edo on 10 August, and remained there until 1 September, when he moved north to Ôyama with his 50,000-strong army. In the meantime, Date Masamune, Maeda Toshinaga and the others were keeping Uesugi Kagekatsu busy; Ieyasu was prepared to strike at Kagekatsu, but did not expect to have to do so.

In Ôsaka, Kikkawa Hiroie was angry over the Môri slight by Mitsunari which forced their clan leader, Terumoto, now nominally the commander of their forces, to remain out of the action. He responded by secretly sending messages to Ieyasu’s generals Kuroda Nagamasa and Ii Naomasa promising that when it was time to fight, the 36,000-man Môri division would not engage the Eastern Army. Môri Hidemoto, Terumoto’s cousin and the man who was to lead the Môri in Terumoto’s stead, urged Terumoto to submit to the Tokugawa before hostilities could break out. He knew the dangers of losing.

On 27 August loyalist forces set upon Fushimi Castle just as Ieyasu and Torii Mototada had expected. The garrison defended it well, holding off for ten days, for Mototada knew that their duty was to delay the Western Army in any way they could; capitulation wasn’t an option.

The defence was getting tired, but could have held longer had not a castle tower been set afire by a traitor within, whose wife and children had been threatened with crucifixion by Mitsunari. There was little left to do. With the castle beginning to burn and the garrison reduced to just 200 men, Mototada led several vicious sorties from the castle against the attackers. Only when it was clear that there was nothing left to hold off the enemy with, and the defenders had been reduced to ten, did the remaining Tokugawa samurai commit suicide as the castle burned around them. It was 6 September. Mitsunari had won, but it had cost him nearly 3000 of his own men to take Fushimi.

A larger cannon such as this would have been used during the sieges of Ueda, Ôtsu, and Fushimi castles. This one was designed specifically to shoot ‘fire arrows’ – exploding, incendiary missiles. Some cannon were actually breach-loading. Several surviving cannon were cast in the form of a dragon, with the muzzle as the dragon’s mouth. (Nagakute Battlefield Museum)

With Fushimi fallen, the Western allies could meet up safely with Mitsunari in Ôgaki Castle for the march north and east, where they would attack Ieyasu from the rear, taking him in his home province of Mikawa.

By 10 September Ieyasu was back in Edo, preparing his forces for the final confrontation.

On 15 September Mitsunari entered Ogaki with images of Ieyasu’s imminent fall playing in his head. He had no idea that Ieyasu was already planning a return to Osaka.

Kiyosu and Gifu castles, only some 15 miles from Ôgaki, were also very close to the Tôkaidô and Nakasendô roads, which were only about 20 miles apart at that point. Whoever controlled those two castles controlled the traffic. As it was, the castles were held by partisans from opposing camps, and each camp was determined to hold theirs and obtain mastery over the other. Ôsaki Genba (called Oni Genba, or ‘Devil Genba’ by his enemies), held Kiyosu Castle for Fukushima Masanori, allied with Ieyasu. Oda Nobunaga’s grandson (who had been raised by the taikô) was in command of the strategically-sited Gifu Castle. He had been advised by his counsellors to side with Ieyasu, but he had elected instead to favour the loyalist cause.

Aware of the dangers the 19-year-old Oda Hidenobu posed as Nobunaga’s grandson, Ieyasu despatched 16,000 men along the Tôkaidô under Fukushima Masanori, Kuroda Nagamasa, Honda Tadakatsu, Ii Naomasa and Hosokawa Tadaoki, to first secure Kiyosu and then take Gifu at all costs. Then, perhaps being cautious, he sent after them a further 15,000 men, under Ikeda Terumasa, Asano Yoshinaga and Yamanouchi Kazutoyo.

The strategic position of Kiyosu Castle made it a location both sides wanted to control. The castle had long ago been Oda Nobunaga’s, but during the conflict of 1600 it was held by Fukushima Masanori, who supported Ieyasu. After Sekigahara, Fukushima Masanori was given Hiroshima (which Ieyasu had taken from the Môri) as his new fief, and Ieyasu gave the castle to his son Tadayoshi.

Ieyasu then sent a third large force – this time 36,000 strong – under the command of his son, Hidetada. This force was to go down the Nakasendô, through central Honshu. All the armies would rendezvous somewhere in the province of Mino, where Ieyasu would join them to take direct command.

The combined Tôkaidô divisions, now numbering 31,000, entered Kiyosu Castle and from there attacked Gifu Castle on 28 September, taking it with little effort. Gifu Castle, perched high atop a lonely mountain, was flying Eastern flags the next day. Oda Hidenobu was sent to the mountaintop monasteries on Kôyasan under guard. He had to wait for Ieyasu to decide his fate after the battles were all over; he was no longer a player.

Ieyasu himself left Edo on 7 October at the head of his own 30,000-man army, making a forced march towards the west. Unlike his slow trek to Edo, which had taken 40 days with only a few thousand men, Ieyasu would move an entire army back nearly the same distance in two weeks.

Perched high on a lonely mountain in Gifu City is Gifu Castle, Ieyasu’s base from which he launched the attack at Sekigahara. It had been the castle of Oda Hidenobu, who chose to support Mitsunari, but two large Eastern forces under Fukushima Masanori and Kuroda Nagamasa had taken it. The castle was not rebuilt, and remained vacant throughout the Tokugawa shogunate. The current donjon is a modern reconstruction.