LEXICAL SEMANTICS AND LEXICOGRAPHY

Scholars’ tasks are not for sissies.

— Frederick W. Danker

Louw and Nida lament, “In no area of New Testament studies is there such a dearth of valid information and such a wealth of misinformation as in lexical semantics.”1 This chapter focuses on the methodology of lexical semantics (drawing particularly on the work of Moisés Silva) and issues in Greek lexicography (drawing on John A. L. Lee). It will be demonstrated that several exegetical mistakes and fallacies can be avoided by a better understanding of the theory of lexemes. Furthermore, certain problems inherent to our current lexicons will be addressed, with a view to using such tools in a responsible manner.2

Lexical semantics, or lexicology, is concerned with the meanings of words.3 Lexicography aims to produce a lexicon — the collected results of lexical semantics for all words of a language. A key distinction between lexical semantics and lexicography is at the level of theory versus practice. While both are concerned with the meanings of words, lexical semantics includes thinking through theoretical issues related to words (lexemes). It provides the framework and methodology for the work of lexicography, which is “the art and science of dictionary-making, carried out by lexicographers.”4 Both lexical semantics and lexicography seek to determine the meaning of lexemes, how lexemes differ from each other, and what the semantic range of each word is. A book such as Moisés Silva’s Biblical Words and Their Meaning deals with the theoretical issues of lexical semantics. A lexicon such as BDAG is a product of lexicography.

This section will treat some of the key theoretical issues in the work of lexical semantics, drawing in particular on the helpful overview of such issues offered by Moisés Silva’s book. Pertinent examples from the Greek New Testament will demonstrate the importance of these theoretical topics.

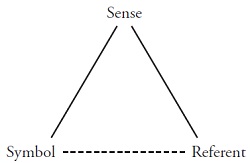

One of the most important distinctions in the theory of lexical semantics, made famous by Ogden and Richards in 1945, is that between symbol, sense, and referent.5 A symbol is a word (either spoken or written); the sense is the image or concept evoked in the mind by the symbol; the referent is the actual thing in the real world that is denoted by the symbol.6 The so-called Ogden-Richards triangle demonstrates the indirect relationship between a word and the thing it points to:

As the Ogden-Richards triangle illustrates, there is no direct relationship between the symbol and its referent. In fact, different languages will each have different symbols for the same referent.7 A cat may be referred to as cat in English, chat in French, Katze in German, or kass in Estonian. They are different symbols and yet share the same referent. Conversely, the referent of a particular symbol can be changed too, so that nice used to mean stupid in Middle English, but now means something else entirely.

The key to such changes in referent on the one hand, or symbol on the other, is the fact that a symbol only has meaning because it signals something in the mind of the language-user. When the word cat is used, most hearers will picture a domestic feline. But others may picture a lion, and some may even picture a jazz musician! In fact, the symbol can point to any of those referents, but only because the symbol evokes a thought or image or concept in the mind first. If normal people have never associated the word cat with jazz musician, then they will not immediately understand the intended referent in the sentence, That horn player is a nice cat.

Additionally, if the sense is changed over time in the minds of a language community, so then the symbol’s referent will change. Thus, eight hundred years ago the word nice caused people to think of the characteristic of stupidity; but now it causes people to think of the characteristic of pleasantness. That horn player is a nice cat must have meant something entirely different in the thirteenth century!

Silva discusses synonymy under the topic of sense relations.8 The sense concept is represented by the middle apex of the Odgen-Richards triangle (see above), and does not involve symbol or referent.9 As Cotterell and Turner explain:

Synonymy is a relationship of identity of sense between two linguistic expressions. . . . Because lexemes usually have a variety of senses (polysemy), it is to be expected that lexemes may be truly synonymous for one or even several of their senses (partial synonymy), but much less probable that they will be synonyms in all of their senses and habitual collocations.10

While it is probably true that no two words are fully interchangeable in all contexts,11 proper synonymy exists when two words overlap enough so that they may be exchanged in certain contexts. Silva’s example is the synonymous use of πνεῦμα and ψυχή; both words are capable of evoking the sense of the immaterial aspect of a person. So, in certain contexts, the two words can be used interchangeably.12 This overlap is a case of proper synonymy (or, in Cotterell and Turner’s terminology, partial synonymy).

However, Silva notes popular-level misuses of the term synonymous, which can afflict biblical interpreters. Often when the term synonymous is misused, what is actually meant is that two words have the same referent. But it is not correct to say that the two words are synonyms, which refers to two words that overlap in sense, not referent. To say that the beloved disciple and the author of the fourth Gospel are synonyms is a mistake; these two terms do not overlap in their sense relations, but in their referent (John).13 This type of mistake about synonymy commonly afflicts biblical interpreters.

An obvious principle of lexical semantics is that context is extremely important for uncovering lexical meaning. Indeed, linguists assign a determinative function to context; “the context does not merely help us understand meaning — it virtually makes meaning.”14 Cotterell and Turner state:

Whereas most words are polysemous (capable of multiple sense meanings), it cannot be emphasized too strongly that this should not be taken to mean that a word is normally capable of a full range of meanings in its use in any one utterance. The context of the utterance usually singles out the one sense, which is intended, from amongst the various senses of which the word is potentially capable.15

What is not always appreciated, however, is the complexity of context. Literary context (called “co-text” by some linguists) is the type of context that is normally the first port of call for students of the New Testament. For lexical semantics, this involves understanding the meaning of a word in light of its surrounding text. What light can be shed on a word through appreciating the sentence in which it belongs, but also the paragraph or pericope, chapter, and book? Indeed, the fact that literary context can range as widely as the sentence through to the chapter or book reveals the phenomenon of “contextual circles.” If we begin with the most immediate context — the sentence — we can move out through a series of concentric circles of context: the paragraph, the section, the chapter, the whole book. All of these levels of context can help to establish the meaning of a word, but which level should have priority? If, for example, the general function of a word throughout a book stands in apparent contrast to its use in a particular sentence, should we allow the sentence-level context to trump the wider context?16

Differing answers to this question alone can yield quite different exegetical results. For instance, debate about the meaning of the δικαιοσύνη – δικαιόω word group in Paul’s usage will sometimes involve this methodological issue. Should we try to determine Paul’s meaning in a particular passage by first establishing how he uses a word everywhere else, or should we just read the word in its immediate context and go from there? Assuming we seek to do both, which level of context takes priority when they are in apparent conflict?

Take Romans 6:7 for example. Most English translations render this verse something like, “For one who has died has been set free from sin” (ESV). Readers of English translations, therefore, may be completely unaware that Paul has used the word δικαιόω in this verse, which is rendered “set free.” But since that word is elsewhere in Romans understood to mean “to justify” or “to declare righteous,” why is it here rendered “to set free”? No doubt this unusual translation of the word is due to its immediate context, which translators have privileged over the wider context in this case.

Speaking of Paul and Romans, another type of literary context is authorial context. The example above is not only related to the use of δικαιόω in Romans, but to Paul’s use overall. It is a common practice to consider a particular author’s use of a lexeme across books, and while this could be understood as a type of theological method, it is properly regarded another type of literary context. It constitutes another contextual circle — wider than a book, it includes all literature authored by the same person. This category belongs to literary context because it considers an author’s literary use of a word; it is just not restricted to one piece of literature.

In addition to literary context, or co-text, lexical semantics takes into account context of situation. Context of situation can be divided into at least two further types of context: situation proper and historical context. The former subdivision refers to the situation into which a document is written. If we consider 1 Corinthians, for example, it is clear that Paul is addressing certain problems within the Corinthian congregation. Working out Paul’s purpose in writing 1 Corinthians not only tells us about his purpose, but relates to contextual issues too. For example, when considering the use of the lexeme εἰδωλόθυτον in 1 Corinthians 8, the situation into which Paul writes may have some bearing on its meaning and function.

The latter subdivision involves understanding the cultural, religious, and sociological backgrounds that relate to a text. For 1 Corinthians, understanding what food sacrificed to idols is about, for example, has direct bearing on our understanding of the text and, in turn, on our understanding of εἰδωλόθυτον. On this word, Louw and Nida state:

Part of the sacrifice was normally burned on the altar, part was eaten during a ritual meal in a temple, and part was sold in the public market. According to Jewish tradition this meat was unclean and therefore forbidden.17

Obviously, the Jewish tradition associated with this meat offered to idols is essential background for understanding Paul’s argument in 1 Corinthians 8. Thus, context of situation considers extra-textual issues that inform our reading of the text and, therefore, our ability to comprehend the usage of lexemes.

One more type of context is pertinent for lexical semantics. This context, as with context of situation, is also extra-textual. Sometimes referred to as “reception history,” this context considers contextualizations that occur subsequent to the writing of the original document.18 While we might be tempted to think that “reception context” is not relevant for understanding an author’s use of a particular lexeme, such an attitude is naïve. The reason that reception context matters is that certain words will be “heard” by modern readers through the lens of how others have understood them in the past.

The δικαιοσύνη – δικαιόω word group is again a classic example of this. Do we simply read these words through the lens of the Protestant Reformation? Does the Reformation skew what these words actually mean? In large part, the so-called New Perspective on Paul argues exactly along such lines — that reception history has caused us to misunderstand Paul. Whether or not such is the case, the point here is that the ways in which others throughout history have understood texts — and particular words in them — affect our reading. Lexical semantics must take this fact into account as we seek to understand words accurately.

A principle of lexical semantics is that every lexeme represents a choice that the author has made. While there are certain idiomatic and linguistic restraints that delimit lexical choice, nevertheless it is significant that an author chooses to use one word when another might have been chosen instead. This relates to the issue of synonymy, addressed earlier in this chapter. It also relates to the principle of paradigmatic choice, explored in chapter 2. In fact, lexical choice is a subset of paradigmatic choice; whenever a lexeme is used, its choice is meaningful against other possible options. To choose one lexeme is to “unchoose” another.

There are a couple of types of lexical choice to consider. One type represents the choice of one referent over another. That is, the choice is determined by what object, person, or action the author wishes to specify. For example, the choice between the words “cat” and “dog” is entirely related to the referent — if the author wants to refer to a dog, she cannot use the word “cat” because it is the wrong sign for the referent. This type of lexical choice sheds some light on the meaning of these two words as we contrast them.

Another type of lexical choice is more nuanced. Rather than a choice that reflects a different referent, this type of lexical choice involves different options for speaking of the same referent. For example, instead of the choice between “cat” and “dog,” this choice is between “canine” and “dog.” In a sentence, the referent would be the same if either word is used, so the difference between them is much more subtle. In fact, this type of lexical choice normally involves synonymous lexemes. For lexical semantics, a choice between synonyms can be difficult to analyze, and yet it is often highly instructive.

A distinguishing feature of Saussure’s legacy is his observation that words are mutually defining, in the sense that they limit each other reciprocally: “The value of a word is first known when we mark it off against the value of neighboring and opposing words. Only as part of the whole does the word have sense; for only in the field is there meaning.”19 Silva points to some scholars who have used this concept for analysis of biblical vocabulary, such as James Barr on “the image of God” and John Sawyer on Hebrew “salvation” terminology.20

For the student of the Greek New Testament, study of lexical fields is greatly assisted through the use of Louw and Nida’s lexicon, since all vocabulary is already arranged according to semantic domains. This means that synonyms and non-synonymous-yet-related words can be compared with relative ease. While such comparisons are not difficult to arrange (with the use of Louw and Nida), the practice is still not standard among interpreters. Rather than simply trying to ascertain which sense of a lexeme is most likely in a particular context, it is worth asking how the use of a different lexeme in its place might have changed the meaning of the utterance. That contrast can illuminate the use of the original lexeme in question.

Lexical ambiguity is a problem for lexical semantics. Exegetes often encounter instances in which the use of a word in a particular text is unclear because it is capable of different meanings. The first issue to work through is whether or not the use of the word is genuinely ambiguous. In other words, it is possible that only one meaning is truly plausible in the context, but this conclusion has yet to be reached. The exegete must study the text and its context carefully, and research the lexeme’s meaning and function, with the expectation that such study will yield a compelling conclusion to the problem. Most of the time, apparent ambiguity is just that — apparent.

In other instances, however, ambiguity is genuine. If such is the case, we must consider two types of ambiguity — deliberate ambiguity and unintended ambiguity. Deliberate ambiguity refers to an author’s choice of a word that is deliberately used in order to convey more than one meaning, or even to keep the meaning slightly vague. As Silva reflects,

It may well be that a great mind occasionally and deliberately uses vague language for specific purposes. In view of the nature of language and communication, however, we should assume one meaning unless there are strong exegetical (literary, contextual) grounds to the contrary.21

Silva thus acknowledges the possibility of deliberate ambiguity, yet helpfully sets parameters for its use. Our default expectation ought to be that there is a nonambiguous solution, unless there are strong reasons to think otherwise.

One possible case of intended ambiguity would be Acts 17:26, in Paul’s Areopagus discourse. So Joshua Jipp says that,

when Paul states that God ἐποίησέν τε ἐξ ἑνὸς πᾶν ἔθνος ἀνθρώπων κατοικεῖν ἐπὶ παντὸς προσώπου τῆς γῆς (17:26a), the interpreter may take ἐξ ἑνός as referring to the biblical story of God’s creation of humanity in Genesis 1. . . . Or the interpreter may interpret the phrase in the Stoic sense whereby all humanity originates in and is a part of, Zeus.22

After suggesting the same type of double meaning in 17:26b, Jipp concludes, “Luke has crafted this sentence in such a manner as to resonate with both biblical and philosophical traditions.”23 If Jipp’s assessment is correct, Acts 17:26 certainly ought to be regarded as an instance of intended ambiguity.

Unintended ambiguity is that which results from the imprecise nature of language and, in particular, the imprecision of exegesis and translation of texts written in a foreign, and ancient, language. The author does not deliberately cause this type of ambiguity; in fact, it might not be the author’s “fault” at all. While language is sometimes ambiguous because a communicator has not given enough concern to clarity, at other times it is due to a lack at the recipient’s end. This is particularly pertinent for us as we wrestle with unintended ambiguity in the New Testament. The author may have been perfectly clear to his original readers and hearers, but less so to us. We are removed from the original context by two thousand years and we are not native speakers of the chosen language. It should not be surprising, therefore, that unintended ambiguity exists. We should be surprised, rather, that there is not more of it!

Sorting through ambiguity remains a difficult task for lexical semantics. Once we have availed ourselves of all the resources and tools at our disposal, there is not much more to be done. We simply must live with the reality that some ambiguity exists. Nevertheless, it is also possible that certain ambiguities will be cleared up through further discovery. For example, the monumental discovery of The Oxyrhynchus Papyri over a hundred years ago has had a dramatic impact on our understanding of Greek in general and on certain lexemes in particular. Ongoing discoveries — though extremely rare at that magnitude — continue to shed light. So, at least in that respect, the further we move away from the time of the New Testament, the closer we get to a complete understanding of its details.

3.2.7 Implications of Lexical Semantics

The foregoing is a simple overview of some key issues within the methodology of lexical semantics. All of these principles are crucial for reading the Greek New Testament with any level of linguistic sophistication. Whenever one wishes to construct a “word study,” or to investigate certain vocabulary related to some theological theme, or simply to understand the use of one word in its context, careful consideration of these lexicological insights will help to avoid common — and unhelpful — pitfalls in interpretation.

Cotterell and Turner offer a list of implications of lexical semantics for theological word studies, which is worth summarizing here.24

Etymology cannot be counted on for determining meaning of words, but only synchronic analysis of the language will aid accurate interpretation.

A lexical form will have several senses, and we must allow for the full diversity of those senses. However, in any one context, a word will only carry one of its possible senses.

A key way to determine the meaning of a word in context is to compare and contrast the sense of the word with other words with related senses.

3.3 New Testament Greek Lexicography

Having discussed some of the key methodological issues of lexical semantics, we turn now to the application of theory as it relates to New Testament Greek. Lexicography is the study of words with a view to their collection in a dictionary. While the New Testament is the corpus we are interested in, the language of the New Testament should not be understood apart from its historical context. That is, the New Testament employs language that is naturally found in the first century, and in that sense our interest in this corpus is artificial. “New Testament Greek” is no different from the Greek used throughout the Koine period (see §1.3.1), and thus any practice of lexicography must take into account the use of words outside the New Testament as well as their use within it. This means that “New Testament Greek Lexicography” is the study of words that appear in the New Testament, without claiming that there is something special about the language of the New Testament. It may be special to us because it is in the New Testament, but it is not special from a linguistic point of view.

3.3.1 Difficulties in Practice

New Testament Greek Lexicography is a difficult and arduous task. First, the practice of understanding words in context is complex and involves careful study of each word as it appears in ancient literature. This task alone can take a lifetime. Second, whenever advances in lexical semantics occur, the task of lexicography is altered. This means that lexicographers are required to update their methods and nuance their results according to the best theoretical advances. It also means that previous results may need adjustment or correction. Third, the language of the New Testament is overlaid with special challenges — not because the language itself is any different from standard first-century Greek, but because of the nature of the New Testament. This corpus has a history of interpretation spanning two thousand years, which will affect the way we read it. There are a myriad of theological issues that play into how we understand the language. Furthermore, new evidence is coming to light even now that requires to be factored in to our conclusions. As the great New Testament lexicographer Frederick Danker once said, “Change spells pain, but . . . scholars’ tasks are ‘not for sissies.’ ”25

One of the challenges of lexicography is that there are two languages of concern, not just one. Greek lexicography does not simply involve the matter of understanding Greek; it also involves English (in our case, at least) and the way that the “receptor” language continues to change. In other words, a lexicon will only make sense to its reader if it is up to date with respect to the reader’s own language. Because English is changing at an incredibly fast rate at the moment, lexicons from a hundred years ago are rendered nearly useless (except for the purpose of studying the history of lexicography). One of the obvious difficulties of lexicography, then, is that it is never finished. As long as the receptor language continues to change, lexicons will require updating.

Another challenge for lexicography is the issue that a word in English may have nuances or connotations that are not shared with the Greek word it translates. Consider this comment from Danker:

Because an expression may be either semantically designative or associative (connotative), it is particularly important that terms used to translate a given expression do not have an associative aspect that distorts the meaning of a term in the source language. The frequent use of “preach” for the term κηρύσσω is a case in point. In English, “preach” suggests a moralistic or didactic mode of communication, whereas “proclaim” may be what a NT writer expresses with the word κηρύσσω, especially when focusing on the distinctive and unique character of a message that comes with divine authority.26

As Danker points out, a problem with the translation “preach” for the Greek word κηρύσσω is that there is a nuance to “preach” that is not implied by the Greek word. This is just one example of a complex problem that lexicographers face for several Greek words. It also highlights the danger of trusting a one-word “gloss” definition for Greek words. We will return to this issue below.

Related to this problem is another that Danker calls the “stained glass” connotation. Due to the long history of New Testament interpretation, there are English words that lexicographers and translators may use that are really only used because of a historical understanding of such English words. The problem here is that the English word no longer has any real currency in contemporary English (or, in fact, means something else entirely). Danker’s example is the English word “grace”:

Associated with the foregoing concerns is the common practice of lexicographers to convey what can be termed a “stained glass” connotation to certain words, with the result that numerous texts take on a patina of exclusiveness not really present in the text. Thereby certain terms lose almost all connection with the socio-cultural context that made them meaningful for their primary audiences. Thus the rendering “grace” for χάρις is not especially meaningful to modern audiences, since the ancient word χάρις was used at numerous levels or registrations to express “generosity.” “Saved through God’s generosity” may not sound churchly, but it expresses the truth: not a theological preference, but a semantic reality that can steer one away from the hazard of dogmatic presuppositions.27

Danker’s phrase “ ‘saved through God’s generosity’ may not sound churchly” captures the sentiment well: “grace” is a “churchly” word, and in normal usage today does not mean what those in the church mean by it. This is obvious by the fact that it nearly always needs to be explained. For someone not used to the “churchly” meaning of “grace,” it must be explained as “unmerited favor,” or, as Danker acknowledges, simply as “generosity.”

Should we keep using English words that do not mean to our contemporaries what they mean to us? Perhaps it can be argued that this is precisely what the early church did with certain technical terms. It could also be argued that a word like “grace” connects us to important historical discussions about salvation, such as those that define the Protestant Reformation. These points are worth considering, but it is clear that from a pure lexicographical standpoint, the English word “grace” is not a great option for translating χάρις.

Yet another problem besetting lexicographers is the practice of illegitimate totality transference. While James Barr famously critiqued this decades ago (also having coined the term), the problem persists.28 This practice refers to reading too much into every use of a particular word. If we collate a full picture of the possible uses of a word and then read that “full picture” into every use of the word, we have illegitimately transferred the “totality” of possible meanings into every use. As Danker explains,

In the case of a term like βλασφημέω, a range of synonyms is possible, but this does not mean that all the meanings we bring to these terms in our receptor language are semantically present in the lexical term and therefore exist in any and every usage of the term in the source language. Context in the source text determines what specific word in the receptor language is adequate to express what the source speaker nuanced through the syntagmatic structure that colored the lexeme.29

A good example is the word σάρξ. This is often used in the New Testament to refer to the fallen, sinful nature, such as in Romans 8:6, “The mind governed by the flesh [σαρκός] is death, but the mind governed by the Spirit is life and peace.” But to assume that every use of σάρξ therefore refers to the sinful nature is to commit the error of totality transference. In Luke 24:39, for example, Jesus says, “Look at my hands and my feet. It is I myself! Touch me and see; a ghost does not have flesh [σάρκα] and bones, as you see I have.” Clearly, Jesus simply refers to his physical body here, not the “sinful nature.”

It is not that the full picture of possible uses of the word is necessarily incorrect; the problem lies in seeing that full picture in every use of the word instead of understanding the particular use of the word as conditioned by its context. Context serves to narrow the possible meanings of a word in use.

All these difficulties illustrate the complexity of the task of lexicography. They also serve to warn us of the dangers of blindly relying on the results of lexicography. It is easy to make mistakes, and the New Testament interpreter must be aware of the potential pitfalls. This leads to the methodological problems inherent to our New Testament Greek lexicons.

No one has drawn more attention to the methodological issues and, well, let’s face it, flaws, in our New Testament Greek lexicons than John A. L. Lee. In a good summary statement of the state of affairs for our lexicons, Lee says, “The concise, seemingly authoritative statement of meaning can, and often does, conceal many sins — indecision, compromise, imperfect knowledge, guesswork, and, above all, dependence on predecessors.”30

Some may be gratified to note that New Testament lexicons are not the only targets of Lee’s critique. Regarding the standard lexicon for Ancient Greek — Liddell-Scott-Jones — Lee is unreserved: it “has no coherent definition method, but relies on glosses; its basic material is derived from predecessors, in some cases descending from the ancient lexicographers; and the organization is chaotic as a result of piecemeal revisions.”31

The situation for New Testament lexicons, however, is further complicated by issues related to the nature of the New Testament. Lee raises these in his third and fourth points below.

First, there is the legacy of the long tradition of indicating meaning by glosses rather than definitions, which leads to many problems (as Louw and others have shown). Secondly, there is the fact that even the latest lexicons derive their material from their predecessors, and a great deal of it has been passed on uncritically over the course of centuries. Thirdly, there is an aspect that I think is not well known: meanings given in the NT lexicons are contaminated by glosses from the standard translations, going back as far as the Vulgate. There is a fourth tendency which has become evident to me lately: NT lexicons are unsystematic in their control of other discussions, and may or may not take up useful contributions to the understanding of the meaning.32

In his important monograph, A History of New Testament Lexicography, Lee acknowledges the widespread accessibility of New Testament lexicons, yet also their failure to achieve their purpose.

There has hardly been a time in four centuries when a recently published New Testament lexicon has not been available for purchase. Yet New Testament lexicography has failed to deliver the results one might expect from such long-sustained attention. Instead of a commodity that provides accurately described meanings and a reliable summation of the relevant data, we have haphazard coverage of the latter and a considerably flawed treatment of the former.33

There are, however, some helpful innovations to be seen in recent contributions to New Testament lexicography. Louw and Nida’s A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament Based on Semantic Domains takes the approach of arranging lexical entries through semantic domains (as the title indicates), rather than via alphabetical arrangement. The chief benefit of such arrangement is that words may be compared to each other according to their similarity or synonymy. Since words are defined in relation to each other, their arrangement based on semantic domains is in itself a useful contribution. Having said that, however, Louw and Nida are open to the critique that their arrangement based on semantic domains is not entirely objective: there is a fair degree of subjective assessment involved in delineating said semantic domains.34

A second innovation of Louw and Nida is to use definitions to indicate meaning, rather than to rely on glosses. This is a major advance that moves us away from problematic reliance on gloss translations that are susceptible to many of the difficulties raised in §3.3.1, above.

The latest edition of Bauer’s lexicon, BDAG — the chief modern lexicon under Lee’s scrutiny — also embraces the significant advance of adding definitions for the majority of words. As with Louw and Nida, this helps to alleviate the traditional problem of reliance on glosses. While Lee acknowledges that there is still a place for glosses — especially for the purpose of learning vocabulary — caution is needed: “It is quite clear that they must not be used as the primary tool for determining meaning . . . nor must the definitions be generated from existing glosses.”35

While the innovations of Louw and Nida and BDAG are encouraging, especially in comparison to other Greek lexicographical traditions, there is much more to be desired. Lee concludes, “Nevertheless, the NT lexical tradition, although it is in an advanced state compared with other areas, would benefit from a thorough rethinking.”36

Subsequent to John Lee’s study of New Testament lexicography, Frederick Danker produced The Concise Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament.37 In response to critiques of previous methodology, Danker’s concise lexicon redressed some of the problems that afflict BDAG. The most significant advance in this regard is the inclusion of extended definitions for many lexical entries — alongside glosses. This volume is useful for students, being less encumbered by detail that they rarely need — and being much less expensive — but it cannot replace BDAG for scholars and many pastors, who will require a more fulsome treatment of lexemes.

John Lee’s critiques of Greek lexicography are not presented without hope for the future. The two major innovations of Louw and Nida’s lexicon (addressed above) set the direction to be followed.

By the adoption of the domain arrangement it has brought into focus lexical structure as a vital element of the vocabulary. The full description of how a word is used requires sensitivity to its place in the complex web of sense-relations of which it is a part. This will need to be one of the concerns of future work. Secondly . . . by rejecting the gloss method and adopting definition as the means of describing meaning, Louw and Nida have blazed a trail to follow.38

Lee also envisages a future for lexicography that is redefined by electronic media. We no longer need to wait for major editions of Greek lexicons to be published in print now that unlimited data can be stored and updated easily by electronic means.39 Lexicographers could create an exhaustive electronic database, which “should be a collection of all the data relevant to the lexicography of the New Testament.”40 Such a project would be a cooperative effort and would be an ongoing, cumulative task so that new data and developments could be incorporated immediately. Lexical information, then, would always be up to date and could be accessed rapidly for exhaustive searching and analysis.

In the meantime, students of the Greek New Testament ought to be grateful that our lexicons are in better shape than those for Ancient Greek generally — and, indeed, for most (if not all) ancient languages. But we need also to be aware of the several problems that have been outlined by John Lee. While we have little choice but to continue to make use of the reference tools at our disposal, we ought to develop a critical engagement of them, rather than imagining that their conclusions have descended from on high.

BDAG remains enormously useful in pointing out ancient sources in which lexemes are found and for outlining the range of senses for each lexeme. However, it is not necessary to agree with the sense that BDAG allocates for each particular use of the lexeme in question. For example, in my monograph Paul and Union with Christ, I made frequent use of BDAG in the study of certain Greek prepositions.41 The range of senses and functions identified for each preposition was enormously useful. However, I found myself regularly disagreeing with the sense attributed to certain prepositions in particular texts. Accordingly, the best approach is to make use of the range of senses outlined in the lexicon, but to examine the use of the lexeme in its context to establish which sense is most likely in that instance. Many times, BDAG will prove to be correct in its sense allocation, but it should not be assumed thus.

Louw and Nida is likewise a helpful tool. The chief advantage here, as anticipated above, is that lexemes can be compared to synonymous or otherwise related words. Since words are mutually defining, Louw and Nida’s work represents a great advance in our ability to understand Greek vocabulary with precision.

Barr, James. The Semantics of Biblical Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1961. Reprint: Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2004.

Black, David Alan. Linguistics for Students of New Testament Greek: A Survey of Basic Concepts and Applications. Second edition. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1995.

Danker, Frederick William. “Lexical Evolution and Linguistic Hazard.” Pages 1 – 31 in Biblical Greek Language and Lexicography: Essays in Honor of Frederick W. Danker. Edited by Bernard A. Taylor, John A. L. Lee, Peter R. Burton, and Richard E. Whitaker. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004.

———. “Review of Lexical Semantics of the Greek New Testament, by E. A. Nida and J. P. Louw, 1992.” JBL 113 (1994): 532 – 33.

Lee, John A. L. A History of New Testament Lexicography. SBG 8. New York: Peter Lang, 2003.

———. “The Present State of Lexicography of Ancient Greek.” Pages 66 – 74 in Biblical Greek Language and Lexicography: Essays in Honor of Frederick W. Danker. Edited by Bernard A. Taylor, John A. L. Lee, Peter R. Burton, and Richard E. Whitaker. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004.

Roberts, Terry. “A Review of BDAG.” Pages 53 – 65 in Biblical Greek Language and Lexicography: Essays in Honor of Frederick W. Danker. Edited by Bernard A. Taylor, John A. L. Lee, Peter R. Burton, and Richard E. Whitaker. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004.

Silva, Moisés. Biblical Words and Their Meaning: An Introduction to Lexical Semantics. Revised edition. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1994.

1. Nida and Louw, Lexical Semantics, 1.

2. It is worth noting that some of the following discussion is not “new” in the sense that it has arisen during the Modern Era of New Testament Greek studies — and, in fact, much of it can be traced at least as far back as James Barr in 1961 — but the issues addressed represent perennial problems that seem not to go away. Thus, lexical semantics and lexicography remain pertinent topics for modern discussions.

3. Moisés Silva, Biblical Words and Their Meaning: An Introduction to Lexical Semantics (rev. ed.; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1994), 10.

4. Crystal, Linguistics and Phonetics, 278.

5. C. K. Ogden and I. A. Richards, The Meaning of Meaning (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1945). Silva uses the term sense in place of Ogden and Richards’s terms thought and reference, which are unnecessarily confusing (Silva, Biblical Words, 102).

6. Silva, Biblical Words, 102.

7. Ibid., 103 – 4.

8. Ibid., chapter 5.

9. Ibid., 121.

10. Cotterell and Turner, Linguistics, 159.

11. Silva, Biblical Words, 121, n, 6.

12. Ibid., 122.

13. Ibid., 121.

14. Ibid., 139.

15. Cotterell and Turner, Linguistics, 175.

16. See Silva, Biblical Words, 156 – 59.

17. Louw and Nida, Greek-English Lexicon, 5.15.

18. Silva, Biblical Words, 147 – 48.

19. Saussure, General Linguistics, 116.

20. Silva, Biblical Words, 161 – 63.

21. Silva, Biblical Words, 151.

22. Joshua W. Jipp, “Paul’s Areopagus Speech of Acts 17:16 – 34 as Both Critique and Propaganda,” JBL 131 (2012): 581 – 82.

23. Ibid., 582.

24. Cotterell and Turner, Linguistics, 178 – 81.

25. Frederick William Danker, “Review of Lexical Semantics of the Greek New Testament, by E. A. Nida and J. P. Louw, 1992,” JBL 113 (1994): 533.

26. Frederick William Danker, “Lexical Evolution and Linguistic Hazard,” in Biblical Greek Language and Lexicography: Essays in Honor of Frederick W. Danker (ed. Bernard A. Taylor et al.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004), 23.

27. Ibid., 24.

28. Barr, The Semantics of Biblical Language, 217 – 18. See also Silva, Biblical Words, 25 – 26; D. A. Carson, Exegetical Fallacies (2nd ed.; Grand Rapids: Baker, 1996), 60 – 61.

29. Danker, “Lexical Evolution,” 26 – 27.

30. John A. L. Lee, “The Present State of Lexicography of Ancient Greek,” in Biblical Greek Language and Lexicography: Essays in Honor of Frederick W. Danker (ed. Bernard A. Taylor et al.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004), 66.

31. Ibid., 68.

32. Ibid., 69.

33. John A. L. Lee, A History of New Testament Lexicography (SBG 8; New York: Peter Lang, 2003), 177.

34. However, see their discussion of the methodology involved in this; Nida and Louw, Lexical Semantics, 107 – 14.

35. Lee, History, 185.

36. Lee, “Present State,” 70.

37. Frederick William Danker with Kathryn Krug, The Concise Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

38. Lee, History, 180.

39. Ibid., 182.

40. Ibid., 183.

41. Constantine R. Campbell, Paul and Union with Christ: An Exegetical and Theological Study (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2012).