We do not care for people messing with our paradigms.

— George H. Guthrie

Verbal aspect has been the most controversial issue within Greek studies in the last twenty-five years. While aspect has been a topic of scholarly discussion since the nineteenth century, the last quarter century has seen the revitalization of the subject, some intense debates about the nature of the Greek verbal system, and many fruitful insights that are of importance for exegesis and translation. Among aspect scholars there is a good level of consensus about a number of significant issues. There are, however, some areas of discussion that remain controversial.

Some of this chapter will overlap with my textbook introduction to the subject, Basics of Verbal Aspect in Biblical Greek.1 It is not possible here to cover material to the same degree as that book (since the book you’re reading now introduces several other topics as well). Furthermore, the previous book allocates a significant portion of its space to exegetical application, which is not a main purpose here. Careful study of Basics of Verbal Aspect is recommended for the student who wishes to understand and apply the insights gleaned from aspect studies.

Furthermore, that book is intended to equip the reader to engage the more serious literature on the subject, such as the monographs by Porter, Fanning, and others. It is hoped that this chapter will lead students to my Basics book, which will in turn lead to the more fulsome literature on the subject. A distinct contribution of this chapter — alongside a brief introduction to the topic — is to canvas some key developments in the discussion that have taken place since the publication of Basics of Verbal Aspect in 2008.2

While some other terminology will be introduced in the next section, it is important to define verbal aspect here. There are different ways in which the term aspect is used within linguistics, but the standard meaning — and that adopted most widely within Greek linguistics — is that aspect refers to viewpoint. The viewpoint is the way in which a verb is used to view an action, either from outside the action or from inside it. Buist Fanning describes aspect thus:

The action can be viewed from a reference-point within the action, without reference to the beginning or end-point of the action, but with a focus instead on its internal structure or make-up. Or the action can be viewed from a vantage-point outside the action, with focus on the whole action from beginning to end, but without reference to its internal structure.3

The external viewpoint (outside the action) is known as perfective aspect; the internal viewpoint (inside the action) is known as imperfective aspect. Perfective aspect views an action “from a distance,” as a whole, and is often used to present an action in summary form — this happened, that happened — without reference to how it happened and without viewing it as though happening. Imperfective aspect views an action “up close,” from within it, and is often used to present an action as unfolding or in progress — this was happening, that happens — without reference to the whole action.

A standard illustration used for describing verbal aspect involves a reporter who is to report on a street parade.4 If the reporter views the street parade from a helicopter, he sees the whole parade from a distance. He can describe the parade in a general way because he sees the whole thing, rather than seeing its details up close. This viewpoint represents perfective aspect. It is the view from the outside — the external viewpoint. If, however, that same reporter views the same street parade from the level of the street rather than from up in a helicopter, his view of the parade is different. This time the reporter is up close to the parade and watches as it unfolds before him. Rather than seeing the parade from a distance and as a whole, the parade is now seen from within. This viewpoint represents imperfective aspect. It is the view from the inside — the internal viewpoint.

Linguists agree that the Greek aorist is perfective in aspect — it is used to convey actions as a whole, and it frequently presents them in a summary fashion. Linguists also agree that the Greek present and imperfect are imperfective in aspect — they are used to convey an action as unfolding, frequently in progress or as a state. There is, however, lively debate about the aspect of the Greek perfect, pluperfect, and future tense-forms.

5.2.1 Distinctions between Tense, Aktionsart, and Aspect5

Verbal aspect is often discussed in relation to two other terms: tense and Aktionsart. It is important that careful delineation is made between the three terms.

5.2.1.1 Tense. In Greek, the verbs have traditionally been labeled as tenses. The aorist is a past tense, the present is a present tense, the future is a future tense, and so on. While there are more technical ways of defining tense, it normally refers to grammatical temporal reference. That is, referring to a particular time-frame is the built-in meaning of a tense. It doesn’t take long when beginning to read the Greek New Testament, however, to discover that tense is not the whole story. We quickly discover verbs in the present tense that refer to the past. There are also past tenses that refer to the present. There are even future-referring past tenses. Furthermore, what’s the difference between two past tenses in Greek? Tense cannot be the whole story with Greek verbs, since there is a difference in meaning between the aorist and imperfect — both past tenses. The nineteenth century answer to this question — the difference between two past tenses in Greek — was not expressed in aspectual terms (perfective versus imperfective). Rather, they tried to define the difference in terms of the type of action, or Aktionsart.

5.2.1.2 Aktionsart. This word literally means “type of action.” There are various types of action. There are punctiliar actions, iterative actions, ingressive actions, and so on. The category of Aktionsart describes the kind of action that took place. If it happened as a once-off, instantaneous event, it is called punctiliar. If the action was repeated over and over, it is called iterative. If the action is seen as beginning, it is called ingressive.

Early on in the academic discussion about such things, there was much confusion between Aktionsart and aspect. These days there is a general consensus as to the difference, and it is vital that we properly understand the distinction. Aktionsart refers to how an action actually takes place — what sort of action it is. Aspect refers to viewpoint — how the action is viewed. They are two different categories.

Take Romans 5:14 as an example. In that verse we are told that “death reigned from the time of Adam to the time of Moses.” The verb “reigned” expresses perfective aspect. This is the view from the helicopter. We are presented with a summary of what happened; we are told simply that it happened. This is the external viewpoint. But when we consider Aktionsart and ask what actually happened, we are able to say a range of other things. For starters, this action took a long time! There were many years between Adam and Moses. Death’s reign between Adam and Moses was an ongoing, expansive event. This was not a once-off, instantaneous type of action. With this example, we can appreciate that there is a clear difference between aspect and Aktionsart. Aspect refers to how the action is viewed: it is viewed externally as a whole. Aktionsart refers to what actually happened: it was an ongoing event that spanned many years.

5.2.2 A Tense-Aspect Confusion

One of the best-known debates within Greek verbal aspect studies is whether or not tense actually exists as a grammatical (semantic) category within the indicative mood. Remember that Greek scholars used to think that tense existed through the whole verbal system, due to the incorrect assumption that Greek was like Latin in this regard. Georg Curtius broke this consensus in the nineteenth century, and from that point on, the consensus has been that tense is restricted to the indicative mood (see §1.2.4).

Porter and others have argued, in effect, that that reassessment did not go far enough, and Greek does not encode tense at the grammatical level at all. While some of the contours of that particular discussion will be outlined in the following sections, it is worth dispelling one common misconception. Often students, and even New Testament professors, will pit aspect against tense as though they are competing categories. They are not. In many languages, including English, aspect and tense happily coexist. While Porter and others claim that tense does not exist in Greek, those who oppose that position do not therefore claim that aspect does not exist. Fanning, for example, affirms the grammatical category of tense in Greek, but also strongly endorses verbal aspect; it’s not one or the other.

Thus the reader should take note that even if one does not agree with the “non-tense” position, you still need to grapple with aspect. No serious scholar doubts its existence in Greek (or any language, for that matter). Whether or not aspect is a legitimate category for Greek is not a debated point, even within the most esoteric treatments of the subject.6

As with the matter of deponency addressed in the previous chapter, it is useful to outline the history of scholarly discussion about Greek verbal aspect in order to understand the trajectory of its development and the significance of certain issues today.7

Curtius was a nineteenth-century comparative philologist (see §1.2.4) who differentiated between different types of meaning expressed by the present and aorist verbal stems, describing the former as a durative action and the latter as a “quickly-passing” action (symbolized as a “line” versus a “point”). His term for this distinction was Zeitart (lit., “type of time”).

He also argued that, in contrast to Latin, temporal meaning in the Greek verbal system was limited to the indicative mood. It is taken for granted now that there is no tense outside the indicative mood in Greek, but this was not formally acknowledged prior to Curtius.

Curtius’s insights were largely accepted in the late nineteenth century, though his term Zeitart was later replaced by the term Aktionsart, since “type of action” was regarded as being a more precise label than “type of time.”

Curtius sparked a period of productive investigation into the nature of the Greek verbal system, from 1890 to 1910. The range of aspect-values that occur in Greek and Indo-European languages was explored, resulting in the creation of a multiplicity of categories and conflicting terminology. Confusion occurred through the interchangeable usage of the terms Zeitart, Aktionsart, and aspect.8

In the mid-1920s the following definitions were crystallized: Aktionsart refers to how the action actually occurs and is primarily lexically determined; aspect refers to a way of viewing an action (Zeitart was dropped). This distinction is widely held today.

While there were several important contributions made through the middle of the twentieth century, such as those of Holt9 and Ruipérez,10 none would have quite the same impact on the modern discussion as the work of K. L. McKay. McKay posited that there were three or four aspects, depending on whether the future was regarded as a proper aspect. The present and imperfect tense-forms are imperfective in aspect, while the aorist is perfective (using our terminology). The future is not really an aspect, but McKay labels it a quasi-fourth aspect anyway. The perfect and pluperfect tense-forms are stative in aspect.

McKay wrote about aspect for the following thirty years and became progressively stronger in his assertions. In fact, he ended up saying that aspect is not just more important than time in the Greek verb, but that time is not there at all, except by implication from the verb’s relationship to its context.11

It was the contributions of Stanley E. Porter12 and Buist M. Fanning13 that put verbal aspect firmly on the map again. Porter analyzed Greek verbal aspect through the prism of Systemic Functional Linguistics. This includes a strong adherence to the distinction between semantics and pragmatics. Semantics refers to values that cannot be canceled; pragmatics vary according to lexeme and context (see §2.6.1).

Like McKay, Porter concludes that Greek is aspectual and not tense-based at all. Since temporal reference is not always expressed by the verb, it therefore cannot be a semantic value. Temporal reference must be pragmatic. Porter also acknowledges three aspects in the Greek verbal system: perfective, imperfective, and stative. He views the future as nonaspectual.

Porter’s contribution has caused the fiercest debate. The “tenseless” position is still in the minority, being rejected by most grammarians.

Fanning’s analysis is more traditional than Porter’s in that tense is still a legitimate category, though aspect is dominant. According to Fanning, there are only two aspects (perfective and imperfective), not three, since stativity is properly regarded as an Aktionsart category, rather than an aspect.

Fanning provides a detailed analysis of how aspect interacts with Aktionsart, indicating how each aspect interacts with certain lexical types to produce predictable Aktionsart outcomes.

Olsen is the first major contributor to follow Porter and Fanning, and her work reflects the enormous debt that the modern discussion owes them.14 Like Fanning, Olsen advocates only two aspects, again affirming that stativity is an Aktionsart value rather than being aspectual.

Olsen utilizes the semantic/pragmatic distinction to argue that some Greek verb forms are tenses and others are not. Those that are consistent in their temporal reference encode it at the semantic level and those that are not consistent do not encode temporal reference at the semantic level.

The burden of Decker’s work is to test Porter’s nontense position in the Gospel of Mark.15 While initially skeptical toward Porter’s approach, he later accepted its validity. Decker isolated one particular issue — the existence or otherwise of semantic temporal reference — and investigated that question thoroughly with reference to the Gospel of Mark.

Evans’s work focuses on the verbal syntax of the Greek Pentateuch and how it matches the underlying Hebrew verb usage.16 On the temporality issue, Evans argues that tense is indeed expressed by the verbal system. On the question of aspects, he also affirms the existence of two aspects, rejecting the category of stative aspect. He suggests that the Greek perfect is imperfective in aspect.

In my two monographs on Greek verbal aspect (the first being on aspect in narrative, in particular), I follow McKay, Porter, and Decker on the issue of tense: it is not regarded as a semantic value of verbs in the indicative mood (except for the future indicative), even though each tense-form has a characteristic temporal reference on the pragmatic level.17 I argue that there are only two aspects, rejecting the category of stative aspect. Following Evans, I argue that the perfect and pluperfect tense-forms are imperfective in aspect.

Mathewson focuses on the function of verbal aspect in the book of Revelation.18 Addressing the phenomenon of shifting tenses in Revelation’s visionary segments, Mathewson accounts for such behavior through verbal aspect. His understanding of aspect and its attendant issues follows Porter, and he provides a helpful genre-specific study.

Cirafesi offers an interesting study that applies verbal aspect to the Synoptic Problem.19 It is an example of how verbal aspect can interact with longstanding problems within New Testament studies. Whereas traditional approaches to Synoptic parallels have assumed Zeitart or Aktionsart values for the verbal system, Cirafesi demonstrates that verbal aspect has stronger explanatory power in accounting for Synoptic tense-form differences.20 As with Mathewson, Cirafesi follows Porter on theoretical issues.

Huffman applies verbal aspect to prohibitions in the Greek New Testament.21 He argues that verbal aspect provides better explanatory power than Aktionsart in understanding prohibitions. From a theoretical point of view, Huffman primarily follows Porter, though he follows my work in some key respects, including the interaction between pragmatics and semantics in the imperatival mood.22

5.4 Verbal Aspect and Temporal Reference

As mentioned above, one of the best-known debates regarding verbal aspect has been whether Greek tense-forms semantically encode temporal reference alongside aspect. While this debate is not resolved, a growing number of aspect scholars have indicated that they do not believe temporal reference to be a core constituent feature of verbs in the indicative mood. Included in this camp are McKay, Porter, Decker, Olsen (for some tense-forms), Campbell (except for the future tense form), Mathewson, Cirafesi, and Huffman. Fanning, Evans, and most Ancient Greek scholars outside New Testament Greek circles remain convinced that tense is a legitimate feature of the indicative verbal system.

As anticipated in §2.6.1, this issue is primarily decided on theoretical grounds. While all contributors affirm the linguistic distinction between semantics and pragmatics, there are differing levels of adherence to it. For those who do not regard temporal reference to be a semantic value of the verb, this is due to a strict adherence to the semantic – pragmatic distinction. The fact that the default temporal reference of all tense-forms (except the future) can be canceled means that it cannot be described as a semantic feature, since “semantic meanings are uniform and uncancelable, whereas pragmatic meanings are variable and cancelable (Grice 1975).”23

For those who are willing to endorse tense, the semantic – pragmatic distinction is not regarded as determinative for this issue. The instances in which tense-forms do not behave “according to the rules” are regarded as exceptions that prove the rule, allowing for language to be rather messy, not always compliant to our neat distinctions. Or, it is thought that tense can be “overruled” by aspect, so that the latter semantic category can render the former undone in certain instances. To my mind, these latter approaches, while common, are not linguistically robust enough. This, then, is an issue in which one’s commitment to linguistic theory makes all the difference.

This is not to say, however, that tense-forms do not have default temporal functions; for example, aorist indicatives normally refer to the past (about 85 percent of instances), and present indicatives normally refer to the present (about 70 percent of instances). Those who adhere to the traditional position may claim that default temporal reference of such forms speaks against the “aspect only” argument. If only aspect exists at the semantic level, how do we account for the clear patterns of temporal reference for indicative verb usage? Something can be said for the way that aspect typically functions, especially within narratives. Since aorists, for example, normally convey the narrative mainline within narrative texts, due to their perfective aspect, they will naturally be past-referring because they occur within past-referring contexts (narrative relates a story in the past). But this is only a partial solution; what about all the aorists that do not occur in narrative and yet so commonly refer to the past?

I have suggested a solution that analyzes the indicative tense-form system from the perspective of aspect in combination with spatial values.24 I argue that Greek verbs semantically encode aspect along with the spatial value of remoteness or proximity (with the exception of the future tense-form, which encodes aspect and future temporal reference). The difference between this description of the semantics of verbs and that of traditional analyses is that semantic temporal reference (“tense”) has been replaced by semantic spatial categories. In other words, while traditional analyses might regard verbs as encoding aspect and tense, I regard verbs as encoding aspect and remoteness, or aspect and proximity.

Following this, I claim that these spatial values of remoteness and proximity, which are semantic, normally express temporal reference on the pragmatic level. This means that remoteness, for example, will most often be pragmatically expressed as temporal remoteness — the action is past-referring. The spatial value of proximity will most often express temporal proximity — present time.25

While my theories about such spatial metaphors have been somewhat controversial — though they resonate in part with the work of Porter and his followers — they offer, I believe, good power of explanation for the usage of indicative verbs.26 The default temporal expression of various forms is accounted for, since a pragmatic function of remoteness is the expression of past temporal reference, and a pragmatic function of proximity is the expression of present temporal reference. The uses of tense-forms that do not, however, conform to their default temporal references may also be accounted for by these spatial metaphors. There are other pragmatic functions that spatial metaphors can implicate beyond temporal reference, such that all usage of the aorist tense-form is explained, whether past-referring or not; all present tense-form usage is explained, whether present-referring or not.

No doubt the issue will remain controversial, as will my proposed solution to it, but one final note will conclude this section. While intense debate has occurred about tense and temporal reference in the Greek indicative mood, it is worth recognizing that it is not the most important issue within verbal aspect studies. This is because the temporal reference of most verbs is already fixed by context, whether one adopts a tenseless view or not. For example, it is simply not possible to regard most aorists in narrative as anything other than past-referring, because of the past-referring (narrative) contexts in which they are found. Such is the case for most instances of indicative mood verbs in Greek.

At the end of the day, whichever theory one accepts, the results of exegesis and translation will not end up very different. Having said that however, there are some instances in which one’s understanding of “tense” does make a difference. This is especially relevant for cases for which traditional approaches to the verb have struggled to account, or have proposed somewhat fanciful explanations for the use of one tense-form when another would be expected.

An example is found in Romans 8:30, with its string of aorist indicatives:

οὓς δὲ προώρισεν, τούτους καὶ ἐκάλεσεν· καὶ οὓς ἐκάλεσεν, τούτους καὶ ἐδικαίωσεν· οὓς δὲ ἐδικαίωσεν, τούτους καὶ ἐδόξασεν.

And those he predestined, he also called; those he called, he also justified; those he justified, he also glorified.

There is no real problem here for the first five aorists (προώρισεν, ἐκάλεσεν, ἐκάλεσεν, ἐδικαίωσεν, and ἐδικαίωσεν), since they naturally make sense as past-referring verbs.27 But ἐδόξασεν causes some trouble for interpreters, since it is not clear in what sense believers have already been glorified. Moo’s commentary is representative of the kinds of comments made about this aorist:

Most interpreters conclude, probably rightly, that Paul is looking at the believer’s glorification from the standpoint of God, who has already decreed that it should take place. While not yet experienced, the divine decision to glorify those who have been justified has already been made; the issue has been settled.28

While the theological sentiment here may be correct, is this really what Paul means by the use of this aorist? It is much more likely that Paul uses all six aorists for a different purpose, which is simply to present these truths in summary form. It may well be a summary “from God’s perspective,” but the point is that these actions are presented as a whole, not necessarily as already completed in the past. The most likely analysis, then, is that all of these aorists are gnomic in Aktionsart (see §5.6.1) and are therefore universal and timeless.29

5.5 Debate over the Greek Perfect

As mentioned above, the most controversial issue in the modern aspect discussion has been whether or not the Greek indicative mood semantically encodes tense. At the SBL Conference in Baltimore in 2013, however, the focus shifted to the issue of the perfect tense-form. The Greek Language and Linguistics Unit hosted a session entitled “The Perfect Storm,” at which Porter, Fanning, and I presented three differing positions on the Greek perfect.

While the perfect had not been the focus of controversy to this point, it is arguably a much more significant issue than temporality and tense. The reality is that even with a tenseless position, the temporal reference of most Greek indicatives in the New Testament is relatively fixed by context. There are a few instances here or there in which one’s position on tense can make a significant exegetical difference in reading the text, but the situation is much more volatile for the Greek perfect. How one understands the semantic nature of the perfect indicative will affect each of its 836 instances in the New Testament. And while the temporality of tense-forms is relatively well controlled by context, many instances of the Greek perfect can be read quite differently depending on the semantic nature that is assumed.

Fanning holds to an aspectually-modified version of the traditional understanding of the perfect. That is, he claims that the Greek perfect indicates a past action with present consequences. Fanning’s reformulation of this description, which was built on Aktionsart categories rather than aspect, attempts to recast the traditional notions of past action and present consequences through aspectual categories. Fanning critiqued Porter for claiming that the Greek perfect is stative in aspect, since stativity is an Aktionsart, not an aspect. He critiqued my view of the perfect by offering Greek examples that in his opinion are not well accommodated by imperfective aspect.

Porter regards the Greek perfect as stative in aspect and thus holds to a three-aspect schema for the verbal system. He defends this through the claim that Greek’s three verbal stems indicate three aspects. Porter critiqued Fanning’s approach as yielding too many exceptions (as with the traditional view). Porter critiqued my approach by repeating arguments made in his written critique, published in the 2011 Festschrift for D. A. Carson.30 This was largely concerned with methodology, taking particular issue with my attempted inductive approach to solving the problem of the perfect.

I regard the perfect as imperfective in aspect. It is clear that many perfects are stative in Aktionsart, and in general linguistics imperfective aspect is regarded as the standard aspect through which to convey stativity. I repeated some of my previous critiques of Fanning and Porter’s positions on the perfect and responded at some length to Porter’s written critique of my views (mentioned above). I defended the claim that there are two aspects in Greek, not three, and that stativity is an Aktionsart, not an aspect.

In Porter’s critique he cited half a dozen general linguists who “endorse the notion of stative aspect,” but I demonstrated that Porter had misrepresented the views of each scholar. In fact, each linguist endorsed the fact that stativity is an Aktionsart and is conveyed by imperfective aspect. I also argued that there are, in fact, four verbal stems in Greek, not three — a fact that presents a major challenge to Porter’s methodology, which assumes that three stems indicates three aspects.

The three papers and responses to each are being published in a collected volume in the Peter Lang series, Studies in Biblical Greek 17, with an introduction by D. A. Carson. For more information about “The Perfect Storm” and our responses to each other’s arguments about the Greek perfect, The Perfect Volume: Critical Discussion of the Semantics of the Greek Perfect Tense under Aspect Theory.

It is most likely going to be up to others to decide who is right about the Greek perfect (if any of us are right). Porter, Fanning, and I will continue to present our best arguments and defenses. In addition to our ongoing interactions, Robert Crellin has recently completed a doctorate on the perfect at the University of Cambridge, so we will no doubt see more discussion from other contributors in future years.

5.6 Verbal Aspect and Exegesis

We turn now to consider some of the uses of verbal aspect in exegesis of the Greek text. After all, complex theoretical discussions are one thing, but how it affects the way we read the Greek New Testament is the ultimate question that we are all interested in. There are several obvious ways in which an understanding of verbal aspect will positively enhance exegesis. Approaching verbs in context through an aspectual understanding will enable the interpreter to engage with the viewpoint conveyed through aspect. Perfective aspect conveys actions through an external viewpoint and often indicates that such actions are to be read as summaries of what happened. Imperfective aspect provides an inside look at actions that occur, whether they be unfolding (=progressing) or stative.

Negatively, an understanding of verbal aspect will help to eliminate common exegetical errors, such as we see with the following example.

Romans 5:6 Ἔτι γὰρ Χριστὸς ὄντων ἡμῶν ἀσθενῶν ἔτι κατὰ καιρὸν ὑπὲρ ἀσεβῶν ἀπέθανεν.

For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for the ungodly.

Some commentators write that because an aorist is used here, Romans 5:6 proves that Christ’s death was a once-off, punctiliar event, never to be repeated, and therefore Christ could not be reoffered time and time again in the Roman mass. While not wanting to deny the once-for-all nature of Christ’s death (cf. 1 Pet 3:18), the aorist in Romans 5:6 does not prove the point at all. Why not? Because that’s not what an aorist means. People who argue such things about this verse base their argument on a faulty understanding of the aorist indicative. A proper understanding of verbal aspect would avoid such an error.31 The aorist’s perfective aspect simply presents Christ’s death from an external perspective, and in this case as a summary of what happened. It is not a punctiliar event just because an aorist is used.32

5.6.1 Aspect and Aktionsart Interactions

Another way in which verbal aspect aids exegesis is through its cooperation with Aktionsart, or, to put it another way, through its partnership with the various other factors in a text that help to construe the nature of an action.

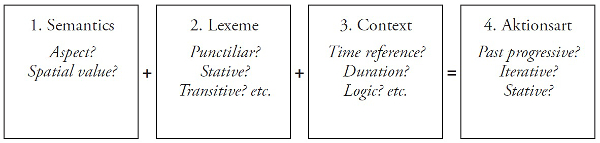

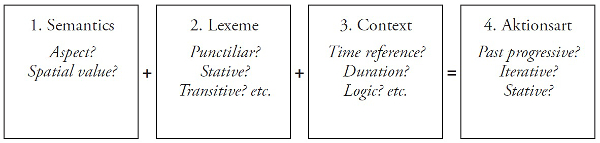

In my textbook introduction, Basics of Verbal Aspect in Biblical Greek, I present a simplified method for understanding aspect and Aktionsart interactions in Greek text. Drawing particularly on Fanning at this point, I acknowledge the usefulness of observing predictable patterns that emerge from the combinations of aspects with lexical types. The combination of aspect, lexeme, and context work together to create pragmatic Aktionsart expressions, or implicatures.

In older grammars and commentaries, various claims are made about the Aktionsarten of verb tenses as though the forms themselves denote categories such as punctiliar, ingressive, constative, and the like. This is simply not the case. There is nothing about an aorist, for example, that is punctiliar in nature. Nevertheless, an aorist is capable of a punctiliar expression when used with a punctiliar lexeme in a context that allows it. In other words, punctiliarity is a pragmatic function, or implicature, of the aorist under certain conditions; it is not what the aorist itself means at the semantic level.

Thus, it is important to recognize that verbal aspect is encoded in verbal forms at the semantic level: it is an uncancelable value that exists in every occurrence of the verb — the aorist is always perfective in aspect; the present is always imperfective in aspect. How these forms then function in context takes into account the semantic value of aspect and its interaction with lexical type and context. The resultant function is called Aktionsart.33

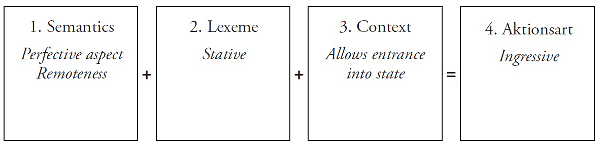

In Basics of Verbal Aspect, I present a four-step process that identifies the key elements in exegeting the function of a verb in context. First, the semantic values of the verb are to be identified (e.g., perfective aspect). Second, the type of lexeme must be taken into account (e.g., punctiliar). Third, relevant elements of the context are considered (e.g., a repeated action is implied). Finally, the Aktionsart is determined based on predictable patterns of the combinations of the previous three elements (e.g., iterative Aktionsart). These steps are represented by various versions of the following diagram:

When semantic features (box 1) combine with pragmatic elements (boxes 2 and 3), the verb creates a specific Aktionsart implicature (box 4). The linguistic term implicature refers to the specific function of a form when in combination with certain pragmatic features. Every verbal form is capable of expressing a variety of implicatures, depending on the combination of pragmatic features at work in any given text. In Basics of Verbal Aspect, the main implicatures of each verb form are explained, together with the factors that can create them. By way of example, the simplified “equations” for the key implicatures of the aorist indicative are summarized below.34

Aorist indicative

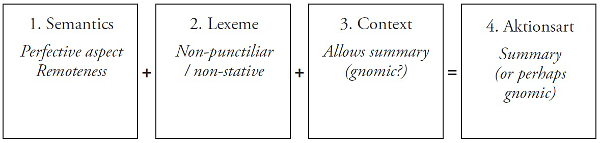

Summary Aktionsart

Perfective aspect with a non-punctiliar, non-stative lexeme can implicate a summary Aktionsart. This is the default function of the aorist indicative and simply expresses that something happened, without further specification.

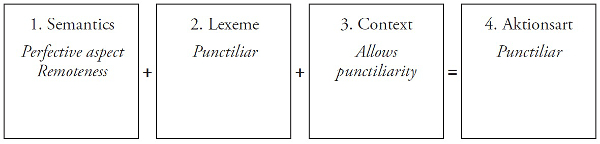

Punctiliar Aktionsart

Perfective aspect with a punctiliar lexeme can implicate a punctiliar Aktionsart. This expresses an action that is once-occurring and instantaneous.

Ingressive Aktionsart

Perfective aspect with a stative lexeme, in a context that indicates entrance into a state or sets a new direction, can implicate an ingressive Aktionsart. This expresses the entrance into a state or the beginning of a new action.

Gnomic Aktionsart

Perfective aspect with any lexeme in a context of “general reality” can implicate a gnomic Aktionsart. This expresses a universal and timeless action.

Present Aorist

Perfective aspect with any lexeme in a present referring context can implicate present temporal reference. Strictly speaking, this is not an Aktionsart, but is a special function of the aorist nonetheless.

Future Aorist

Perfective aspect with any lexeme in a future referring context can implicate a future aorist. More common than the present aorist, this is another special function of the aorist.

Some examples illustrate how this all works out in various texts.

John 19:34 ἀλλ’ εἷς τῶν στρατιωτῶν λόγχῃ αὐτοῦ τὴν πλευρὰν ἔνυξεν, καὶ ἐξῆλθεν εὐθὺς αἷμα καὶ ὕδωρ.

But one of the soldiers pierced his side with a spear, and at once blood and water came out.

1. Semantic meaning of the verb. The aorist indicative semantically encodes perfective aspect and the spatial value of remoteness.

2. Contribution of the lexeme. The lexeme is punctiliar; it is an instantaneous action.

3. Function in context. The context allows punctiliarity.

Romans 3:23 πάντες γὰρ ἥμαρτον καὶ ὑστεροῦνται τῆς δόξης τοῦ θεοῦ

For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.

1. Semantic meaning of the verb. The aorist indicative semantically encodes perfective aspect and the spatial value of remoteness.

2. Contribution of the lexeme. The lexeme is not punctiliar or stative.

3. Function in context. The context allows summary. Could perhaps provide a gnomic context: “For all sin...,” but this is tentative at best.

John 1:10 ἐν τῷ κόσμῳ ἦν, καὶ ὁ κόσμος δι’ αὐτοῦ ἐγένετο, καὶ ὁ κόσμος αὐτὸν οὐκ ἔγνω.

He was in the world, and the world was created through him, yet the world did not recognize him.

1. Semantic meaning of the verb. The aorist indicative semantically encodes perfective aspect and the spatial value of remoteness.

2. Contribution of the lexeme. The lexeme is stative.

3. Function in context. The context allows the entrance into a state.

By careful consideration of verbal aspect, the lexeme of the verb in question, and the context, the student can discern the function of a verb in its context. While there is admittedly some subjectivity involved (especially in evaluating the context), this four-step process is a more reliable guide than the (sometimes questionable) intuition of interpreters of yesteryear. It is comparatively objective, and at the very least it allows for scrutiny of the process and results it produces.

5.6.2 Aspect and Narrative Structure

Another area of exegetical import is the way in which verbal aspect functions to structure narrative texts. These observations about verbal aspect within narrative were developed in my monograph, Verbal Aspect, the Indicative Mood, and Narrative, and the following summarizes some its main conclusions.

First, let us consider the structure of narrative texts.35 Several strands of discourse may be delineated within the narrative text type. The most basic distinction within narrative is that between narrative proper and discourse proper; that is, those parts of the narrative that are communicated through event-based story, and those parts that are communicated through the reporting of speech, thought, and so on (reported discourse).36

Within this basic distinction, further distinctions are possible. Narrative proper may be understood as the combination of mainline and offline strands. Mainline communicates the sequential events that form the skeletal structure of the entire narrative text, while offline material provides supplemental information that comments on, explains, and fills out the mainline action.37

Discourse proper consists of direct discourse, which reports speech as though it is unfolding in real time; indirect discourse, which reports the content of speech or thought; and authorial discourse, which consists of the direct communication of the author to the reader by way of appeal or explanation.

It is argued, in agreement with previous research, that these various strands of discourse not only shape narrative texts, but they provide the macrostructure in which verbal aspect functions.38 The various aspects are typically aligned with these strands of discourse, such that predictable patterns are formed whereby each aspect in the indicative mood has a default association with a particular strand of discourse. These patterns may be summarized as following.

| DISCOURSE STRANDS AND INDICATIVE TENSE-FORM PATTERNS | |

| Mainline material | Aorist indicative |

| Offline material | Imperfect and pluperfect indicatives |

| Direct discourse | Present, perfect, and future indicatives |

| Indirect discourse | Present and perfect indicatives |

| Authorial discourse | Present and perfect indicatives |

These patterns of indicative verbal distribution are created through the functionality of verbal aspect. Perfective aspect is inherently suited to the reporting of events on the narrative mainline (aorist indicative); imperfective aspect inherently suits the provision of offline material (imperfect and pluperfect indicatives), as well as the various types of reported discourse found in narrative (present and perfect indicatives).

Having developed an aspectual model for the Greek verbal system on the basis of verbal patterns and their relationships to the various strands of discourse within narrative texts, we are able to pick out the structure of Greek narrative texts by identifying the locations of indicative verbal forms. In the following example, indicative verbs are double-underlined, and beside each Greek excerpt is a simple structural outline depicting only the indicative verbs. The outline portrays mainline material on the left with a dot point next to the relevant verb, offline material indented with a dash next to the relevant verb, and reported discourse further indented and within square brackets. The outline is spaced so as to correspond approximately to the position of the verbs within the excerpt.

John 7:28 – 32

28 ἔκραξεν οὖν ἐν τῷ ἱερῷ διδάσκων ὁ Ἰησοῦς καὶ λέγων· κἀμὲ οἴδατε καὶ οἴδατε πόθεν εἰμί· καὶ ἀπ’ ἐμαυτοῦ οὐκ ἐλήλυθα, ἀλλ ἔστιν ἀληθινὸς ὁ πέμψας με, ὃν ὑμεῖς οὐκ οἴδατε· 29 ἐγὼ οἶδα αὐτόν, ὅτι παρ’ αὐτοῦ εἰμι κἀκεῖνός με ἀπέστειλεν. 30 Ἐζήτουν οὖν αὐτὸν πιάσαι, καὶ οὐδεὶς ἐπέβαλεν ἐπ’ αὐτὸν τὴν χεῖρα, ὅτι οὔπω ἐληλύθει ἡ ὥρα αὐτοῦ. 31 Ἐκ τοῦ ὄχλου δὲ πολλοὶ ἐπίστευσαν εἰς αὐτὸν καὶ ἔλεγον· ὁ χριστὸς ὅταν ἔλθῃ μὴ πλείονα σημεῖα ποιήσει ὧν οὗτος ἐποίησεν; 32 ἤκουσαν οἱ Φαρισαῖοι τοῦ ὄχλου γογγύζοντος περὶ αὐτοῦ ταῦτα, καὶ ἀπέστειλαν οἱ ἀρχιερεῖς καὶ οἱ Φαρισαῖοι ὑπηρέτας ἵνα πιάσωσιν αὐτόν. |

• ἔκραξεν |

|

[οἴδατε οἴδατε εἰμί ἐλήλυθα ἔστιν οἴδατε οἶδα εἰμι ἀπέστειλεν] | |

— Ἐζήτουν |

|

|

• ἐπέβαλεν |

|

— ἐληλύθει |

|

| • ἐπίστευσαν |

|

— ἔλεγον |

|

[ποιήσει ἐποίησεν] |

|

• ἤκουσαν |

|

• ἀπέστειλαν |

This example demonstrates the way in which the verbal outline accurately reflects the shape of the narrative. Mainline is carried by the aorist indicatives on the left of the outline, while offline material is carried by imperfects and one pluperfect. The reported discourse is carried by presents, perfects, two aorists, and a future indicative.39

The value of producing a chart of narrative text in such a way is to trace the structuring role that aspect plays in all narratives. It becomes a useful way to delineate the flow and development of narrative texts, and in this way the study of verbal aspect serves the process of exegesis.

5.6.3 Aspect and Planes of Discourse

One area of contention regarding the exegetical implications of verbal aspect concerns Porter’s planes of discourse.40 Porter argues that the aspects contribute to planes of discourse in text, in which three planes may be discerned: background, foreground, and frontground. Porter’s model accordingly attributes least significance to perfective aspect (aorist tense-form), which provides background information; greater significance to imperfective aspect (present and imperfect), which provides foreground information; and greatest significance to stative aspect (perfect and pluperfect), which provides frontground information.41 The pluperfect is thus well suited to evaluate Porter’s planes of discourse model, since according to him it should display high prominence within frontground information.

Furthermore, Porter regards the pluperfect and perfect tense-forms as the most heavily marked, meaning that they carry the greatest significance when used in opposition to the perfective and imperfective aspects.42 Two of the factors that Porter envisages as contributing to this markedness are the relatively infrequent use of the perfect and pluperfect and their comparative morphological bulk: “The Perfect has the most morphological bulk of all the tenses, because of its unthematic root, endings and reduplication.”43 “Morphologically the Pluperfect form is particular unwieldy . . . often with an augment besides Perfect reduplication . . . and primary endings with ει (or η) thematic vowels attached to the Perfect stem.”44 It is this markedness that underpins Porter’s planes of discourse theory.

Hatina tests Porter’s theory by examining the perfect tense-forms in Galatians45 and Colossians.46 He concludes that “the hypothesis is plausible in some cases at this preliminary stage. . . . It is generally not the case that the perfect is found in a comparatively insignificant position.”47 Reed and Reese are not quite so satisfied: though they regard stative aspect to be the most accentuated aspect, they admit that “in the event that the aspectual function conflicts with its value of prominence, verbal aspect takes precedence.”48 This admission has important implications in that prominence is not seen to be grammaticalized in the verb. They state that “the use of verbal aspect . . . to indicate prominence is a secondary role — a pragmatic function of grammar — and, thus, a discourse function not a morphological function of Greek grammar.”49 Reed and Reese conclude that it cannot be claimed that every time a particular tense-form occurs, it should always be interpreted in terms of prominence.50 Prominence is therefore a matter of pragmatics, not semantics.

Silva is more skeptical yet, claiming that

no reasonable writer would seek to express a major point by leaning on a subtle grammatical distinction — especially if it is a point not otherwise clear from the whole context (and if it is clear from the context, then the grammatical subtlety plays at best a secondary role in exegesis).51

Rather, Silva argues that the choice of aspect is largely determined by the circumstances, rather than to accentuate the point,52 and thus “an interpreter is unwise to emphasize an idea that allegedly comes from the use of a tense (or some other subtle grammatical distinction) unless the context as a whole clearly sets forth that idea.”53

Indeed, while the perfect generally may be found in comparatively significant positions, the same cannot easily be said of the pluperfect, and despite some occurrences of the pluperfect that may be regarded as prominent in their contexts, several others may not. Admittedly, there is no objective test as to the prominence or otherwise of these verbs; subjective appreciation of context must be our guide. These examples demonstrate nonprominent usages of the pluperfect.

Matthew 13:2

καὶ συνήχθησαν πρὸς αὐτὸν ὄχλοι πολλοί, ὥστε αὐτὸν εἰς πλοῖον ἐμβάντα καθῆσθαι, καὶ πᾶς ὁ ὄχλος ἐπὶ τὸν αἰγιαλὸν εἱστήκει.

Such great crowds gathered to him, that he got into a boat and sat down; and the whole crowd was standing on the beach.

Luke 4:29

καὶ ἀναστάντες ἐξέβαλον αὐτὸν ἔξω τῆς πόλεως καὶ ἤγαγον αὐτὸν ἕως ὀφρύος τοῦ ὄρους ἐφ’ οὖ ἡ πόλις ᾠκοδόμητο αὐτῶν ὥστε κατακρημνίσαι αὐτόν·

They got up and cast him out of the city and took him to the brow of the hill on which their city was built, so that they could throw him down the cliff.

John 18:18

εἱστήκεισαν δὲ οἱ δοῦλοι καὶ οἱ ὑπηρέται ἀνθρακιὰν πεποιηκότες, ὅτι ψῦχος ἦν, καὶ ἐθερμαίνοντο· ἦν δὲ καὶ ὁ Πέτρος μετ’ αὐτῶν ἑστὼς καὶ θερμαινόμενος.

Now the slaves and officers had made a charcoal fire, because it was cold, and they were standing and warming themselves; Peter also was with them, standing and warming himself.

Clearly these pluperfects are not prominent; only by improbable explanations could they be understood as such. Indeed, approximately one third of pluperfects in the New Testament are not easily regarded as being prominent.54

Moreover, Porter’s conception of morphological bulk, and its role in indicating prominence, seems somewhat contrived. While the pluperfect perhaps should theoretically carry greatest morphological bulk, the reality is that many pluperfects are not comparatively large, as the forms ᾔδει ἐγεγόνει, εἱστήκει, and εἰώθει demonstrate. Another of Porter’s indicators of markedness, however, is the low frequency of the pluperfect, and since there is no question as to the form’s low frequency, this indicator of markedness is not invalid. It is reasonable to conclude, therefore, that any use of the pluperfect does represent a significant choice. This markedness, however, as seen above, does not necessarily result in the prominence of the pluperfect.

The demonstrable lack of prominence of at least one third of pluperfects in the New Testament suggests that Porter’s planes of discourse model does not adequately accommodate pluperfect usage. For the pluperfect at least, prominence is best determined according to context, and is not grammatically marked according to verbal forms. As such, it seems prudent to call into question the planes of discourse model in general: if it does not accommodate the pluperfect, how accurate is the model?

It is far more secure to recognize the usage of the pluperfect in terms of providing supplemental, descriptive, and explicatory material, which together is designated by Hopper as background information. The provision of such information is the normal pragmatic expression of the aspect of the pluperfect.

There is a great deal of agreement about various significant issues within Greek verbal aspect studies, such as how to define aspect, the distinction between semantics and pragmatics, the importance of aspect in the verbal system, and the awareness that exegesis of the Greek New Testament desperately needs to be well-informed regarding these insights. While debate about the perfect is probably the most important issue of contention among aspect scholars, it is not the only one. Other issues require further research, debate, and, hopefully, resolution.

The issue of whether Greek verbs are tenses remains unresolved. Do Greek verbs encode temporal reference at the semantic level, or is temporal reference a pragmatic category created through the combination of semantic features and context? How many aspects are there? Everyone agrees that there are at least two (perfective and imperfective), but what about a third (stative) aspect? There is also disagreement about the aspectual nature of the Greek future tense-form. Does it convey aspect? If so, which aspect? Following “The Perfect Storm,” the aspectual nature of the future indicative is probably the next area that requires focused attention from scholarship. Two doctoral students have recently completed dissertations on the Greek future — Francis Pang at McMaster Divinity College, and Craig Long at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. We look forward to their contributions.

While verbal aspect remains the most controversial and volatile area of research in Greek studies today, much has been gained from the discussion. As further research is conducted and methodological issues are carefully considered, I am hopeful that more will be achieved in terms of clarity and consensus. The worst thing that could happen, however, is that other students of the Greek New Testament decide to remain disengaged from verbal aspect, citing that “the scholarship is unresolved.” In fact, in the wider world, many areas of scholarship face such debates, but this does not mean that they are not studied, taught, and applied. Students of Greek simply must become conversant with what is going on in aspect studies.

Even just employing the insights about which there is agreement has potential to yield significant advances in exegesis and translation. The most obvious way in which to begin to incorporate the insights of verbal aspect studies into Greek exegesis is to adopt the four-step method outlined in Basics of the Verbal Aspect (see §5.6.1). While the approach is oversimplified at certain points (especially regarding lexical analysis, which is enormously complex on its own), it provides a method for approaching aspect and Aktionsart interactions in the text. No doubt more research is needed here, and Basics of Verbal Aspect is only a starting point. But a starting point is what’s needed for those who have not yet started.

Another important area for future research is the interaction of verbal aspect in different text-types, or genres. My monograph, Verbal Aspect, the Indicative Mood, and Narrative: Soundings in the Greek of the New Testament,55 explores the function of aspect in narrative texts (see §5.6.2). David Mathewson’s Verbal Aspect in the Book of Revelation explores aspect in the apocalyptic genre. While other studies have of course included consideration of epistolary material, there is scope for more work to be done on aspect’s function in how epistles operate at the discourse level.

Related to genre is the issue of idiolect — an individual’s “dialect.” The relationship between idiolect and verbal aspect is an interesting one, especially with respect to frequency and patterns of usage. An obvious problem that this relationship has potential to address is the so-called Synoptic Problem, so far as idiolect is able to explain certain changes from, say, Markan to Lukan usage. This issue has begun to be explored in Cirafesi’s work (see §5.3.11), and idiolect is explored further in the next chapter of this book.

Furthermore, there is scope for additional research on the function of aspect in the nonindicative verb forms. Another monograph of mine, Verbal Aspect and Non-Indicative Verbs: Further Soundings in the Greek of the New Testament addresses this area directly, but there is more to be done, perhaps by way of focused research on individual moods, such as the subjunctive. In light of this need, it is encouraging to see Huffman’s recently released volume on prohibitions (including the imperative and subjunctive moods).

Campbell, Constantine R. Verbal Aspect, the Indicative Mood, and Narrative: Soundings in the Greek of the New Testament. SBG 13. New York: Peter Lang, 2007.

———. Verbal Aspect and Non-Indicative Verbs: Further Soundings in the Greek of the New Testament. SBG 15. New York: Peter Lang, 2008.

———. Basics of Verbal Aspect in Biblical Greek. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008.

Cirafesi, Wally V. Verbal Aspect in Synoptic Parallels: On the Method and Meaning of Divergent Tense-Form Usage in the Synoptic Passion Narratives. LBS 7. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

Decker, Rodney J. Temporal Deixis of the Greek Verb in the Gospel of Mark with Reference to Verbal Aspect. SBG 10. New York: Peter Lang, 2001.

Evans, T. V. Verbal Syntax in the Greek Pentateuch: Natural Greek Usage and Hebrew Interference. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Fanning, Buist M. Verbal Aspect in New Testament Greek. Oxford Theological Monographs; Oxford: Clarendon, 1990.

Huffman, Douglas S. Verbal Aspect Theory and the Prohibitions in the Greek New Testament. SBG 16. New York: Peter Lang, 2014.

Mathewson, David L. Verbal Aspect in the Book of Revelation: The Function of Greek Verb Tenses in John’s Apocalypse. LBS 4. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

McKay, K. L. A New Syntax of the Verb in New Testament Greek: An Aspectual Approach. SBG 5. New York: Peter Lang, 1994.

Olsen, Mari Broman. A Semantic and Pragmatic Model of Lexical and Grammatical Aspect. Outstanding Dissertations in Linguistics. New York: Garland, 1997.

Porter, Stanley E. Verbal Aspect in the Greek of the New Testament with Reference to Tense and Mood. SBG 1. New York: Peter Lang, 1989.

Porter, Stanley E., Buist M. Fanning, and Constantine R. Campbell. The Perfect Volume: Critical Discussion of the Semantics of the Greek Perfect Tense under Aspect Theory. Introduction by D. A. Carson. SBG 17. New York: Peter Lang, 2015.

1. Constantine R. Campbell, Basics of Verbal Aspect in Biblical Greek (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008).

2. Greek verbal aspect is the chief area in which my own research in Greek has been focused, with two monographs alongside the textbook introduction. Therefore, my perspectives and conclusions will naturally feature in this chapter in a way that is more prominent than in other chapters of this book. It is not my intention, however, simply to “push my own barrow,” but to introduce the reader to the important scholars, advances within the field, and issues of controversy. Regarding the latter, the reader will forgive me if my evaluations of certain controversies are self-endorsing! This is because I happen to believe they are correct — I wouldn’t hold such views otherwise — but my intention nevertheless is to present a fair depiction of the state of affairs, and the reader is of course free to form their own conclusions.

3. Fanning, Verbal Aspect, 27.

4. The illustration originates with Isaćenko and is adopted by Porter. See A. V. Isaćenko, Grammaticheskij stroj russkogo jazyka v sopostavlenii s slovatskim: Morfologija (Bratislava: The Slovak Academy of Sciences Press, 1960); Porter, Verbal Aspect, 91.

5. This section is taken from my Basics of Verbal Aspect, 21 – 22.

6. To this end, the common term verbal aspect theory should be amended simply to verbal aspect. The use of the word theory in this instance does not mean unproven (as in the sentence, “Well, it’s just a theory”), but rather refers to theoretical discussions about aspect. Nevertheless, people often assume the former meaning of the word theory, and therefore regard the whole discussion as an unproven hypothesis. This is not the case, and for that reason I endorse abandoning the (potentially) misleading expression altogether.

7. This section represents a summary of my Basics of Verbal Aspect, 26 – 32.

8. See Fanning, Verbal Aspect, 9 – 33, for more on this period.

9. Jens Holt, Études d’aspect (Acta Jutlandica Aarsskrift for Aarhus Universitet 15.2; Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1943).

10. Martín S. Ruipérez, Estructura del Sistema de Aspectos y Tiempos del Verbo Griego Antiguo: Análisis Funcional Sincrónico (Theses et Studia Philologica Salmanticensia 7; Salamanca: Colegio Trilingüe de la Universidad, 1954).

11. McKay, A New Syntax, 39.

12. Porter, Verbal Aspect.

13. Fanning, Verbal Aspect.

14. Mari Broman Olsen, A Semantic and Pragmatic Model of Lexical and Grammatical Aspect (Outstanding Dissertations in Linguistics; New York: Garland, 1997).

15. Rodney J. Decker, Temporal Deixis of the Greek Verb in the Gospel of Mark with Reference to Verbal Aspect (SBG 10; New York: Peter Lang, 2001).

16. T. V. Evans, Verbal Syntax in the Greek Pentateuch: Natural Greek Usage and Hebrew Interference (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001).

17. Constantine R. Campbell, Verbal Aspect (Indicative Mood); idem, Verbal Aspect and Non-Indicative Verbs: Further Soundings in the Greek of the New Testament (SBG 15; New York: Peter Lang, 2008).

18. David L. Mathewson, Verbal Aspect in the Book of Revelation: The Function of Greek Verb Tenses in John’s Apocalypse (LBS 4; Leiden: Brill, 2010).

19. Wally V. Cirafesi, Verbal Aspect in Synoptic Parallels: On the Method and Meaning of Divergent Tense-Form Usage in the Synoptic Passion Narratives (LBS 7; Leiden: Brill, 2013).

20. Ibid., 166.

21. Huffman, Verbal Aspect Theory and the Prohibitions.

22. E.g., ibid., 100 – 103, 511.

23. Olsen, Aspect, 219.

24. The following paragraphs are based on Basics of Verbal Aspect, 129 – 30.

25. “It should be understood that the terms ‘remoteness’ and ‘proximity’ are best understood as metaphors. When an aorist is used, it does not mean that the action occurred far away in a geographical sense, just because it encodes the spatial value of remoteness. For example, if I were to describe an action that occurred on my street, I am not forced to employ a proximate tense-form simply because it happened close to me physically. By the same token, if the action occurred in Cuba, I would not be forced to use a remote tense-form simply because Cuba is on the other side of the planet from Australia. To conclude that an action must have occurred at a physical distance because remoteness is encoded by the verb is to take remoteness literally — or concretely — rather than metaphorically” (ibid., 129 – 30).

26. It is worth noting that spatial theories of language are not “weird”; “The connection between space and time is arguably part of any language. Languages that encode time through their verbal system (i.e., languages that have tenses) did not necessarily always do this. All languages change over time, and one of the major changes that can be observed in the history of a number of languages is that the verbal system tends to begin as a spatial system, and later develops into a temporal one. In other words, the idea that verbs should primarily convey actions in a spatial, rather than temporal, way is not unusual in the history of language, and several languages began in such a way” (ibid., 131).

27. But only if Paul is referring to those who have already been called and justified. If he has in mind all those whom God has predestined, then four of these five aorists become problematic, since not all those predestined have yet been called and justified.

28. Douglas J. Moo, The Epistle to the Romans (NICNT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996), 536.

29. See Campbell, Basics of Verbal Aspect, 88 – 89, 147.

30. Stanley E. Porter, “Greek Linguistics and Lexicography,” in Understanding the Times: New Testament Studies in the 21st Century (ed. Andreas J. Köstenberger and Robert W. Yarbrough; Wheaton: Crossway, 2011), 46 – 54.

31. Carson helpfully lists a catalogue of exegetical errors made by scholars with reference to the aorist indicative. See Carson, Exegetical Fallacies, 68 – 73.

32. See Campbell, Basics of Verbal Aspect, 13 – 16, for other examples of exegetical issues that aspect addresses.

33. This paragraph and the preceding one are taken from my Colossians and Philemon: A Handbook on the Greek Text (Baylor Handbook on the Greek New Testament; Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2013), xxii.

34. These summaries are taken from Campbell, Colossians and Philemon, xxiv. See xxiv – xxvii for the full range of implicatures across tense-forms. The descriptions in that volume summarize information developed throughout Basics of Verbal Aspect.

35. The remainder of this section is based on Campbell, Verbal Aspect (Indicative Mood), 239 – 47.

36. As Dooley and Levinsohn say, “the contents of reported speeches . . . are embedded in the overall structure of the narrative.” Robert Dooley and Stephen H. Levinsohn, Analyzing Discourse: A Manual of Basic Concepts (Dallas: SIL International, 2001), 128.

37. See Stanley E. Porter, “Prominence: An Overview,” in The Linguist as Pedagogue: Trends in the Teaching and Linguistic Analysis of the Greek New Testament (ed. Stanley E. Porter and Matthew Brook O’Donnell; Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix, 2009), 57 – 58.

38. See, e.g., Paul J. Hopper, “Aspect and Foregrounding in Discourse,” in Discourse and Syntax (ed. Talmy Givón; Syntax and Semantics 12; New York: Academic Press, 1979), 213 – 41; Robert E. Longacre, “Mark 5.1 – 43: Generating the Complexity of a Narrative from Its Most Basic Elements,” in Discourse Analysis and the New Testament: Approaches and Results (eds. Stanley E. Porter and Jeffrey T. Reed; JSNTSup 170; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1999), 169 – 96.

39. It is to be stressed that this function of indicative verbs in narrative is pragmatic only; the functions can be cancelled. For instance, it is possible to find imperfect indicatives carrying the narrative mainline, alongside aorists, as in Luke 2:7; 24:30; and John 4:30. The point here, however, is that aspect in the indicative mood displays predictable patterns within narrative, even if these patterns are not absolute. See Campbell, Verbal Aspect (Indicative Mood), 96 – 98.

40. This section is based on ibid., 233 – 37.

41. Stanley E. Porter, Idioms of the Greek New Testament (2nd ed.; Biblical Languages: Greek 2; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1994), 23; “In Defence of Verbal Aspect,” in Biblical Greek Language and Linguistics: Open Questions in Current Research (ed. Stanley E. Porter and D. A. Carson; JSNTSup 80; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1993), 35. Reed and Reese recategorize these as BACKGROUND, THEME and FOCUS; see Jeffrey T. Reed and Ruth A. Reese, “Verbal Aspect, Discourse Prominence, and the Letter of Jude,” Filologia Neotestamentaria 18.9 (1996): 187 – 88.

42. Porter, Idioms, 22.

43. Porter, Verbal Aspect, 246.

44. Ibid., 289.

45. Thomas R. Hatina, “The Perfect Tense-Form in Recent Debate: Galatians as a Case Study,” Filologia Neotestamentaria 15/8 (1995): 3 – 22.

46. Thomas R. Hatina, “The Perfect Tense-Form in Colossians: Verbal Aspect, Temporality and the Challenge of Translation,” in Translating the Bible: Problems and Prospects (ed. Stanley E. Porter and Richard S. Hess; JSNTSup 173; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1999).

47. Ibid., 249 – 50.

48. Reed and Reese, ‘Discourse Prominence’, 190.

49. Ibid., 190 [italics are original].

50. Ibid. 190.

51. Silva, God, Language, and Scripture, 115 [italics are original].

52. Ibid. 118.

53. Ibid. 118. See also Moisés Silva, “Discourse Analysis and Philippians,” in Discourse Analysis and Other Topics in Biblical Greek (ed. Stanley E. Porter and D. A. Carson; JSNTSup 113; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1995), 105.

54. See also Mark 10:1; 14:40; 16:9; Luke 8:2, 29, 38; 19:15; 22:13; 23:35, 49; John 1:31; 7:37; 11:30, 44; 18:2, 16; 20:11; Acts 4:22; 7:44; 8:27; 9:7; 12:9; 20:16; Rev 7:11.

55. Rodney Decker’s monograph also deals with aspect in narrative (Mark’s gospel), but his focus is not on the function of aspect in the narrative genre per se; he is primarily interested in the question of temporal reference.