CHAPTER FOUR

WORKER MILITANCY AND WARTIME INDUSTRIAL CONFLICT

“The men in the brass foundry call him ‘Big Bill.’ “But Bill Zastrow, steward of the Brass Foundry workers, is more than big. He’s a 100% Union guy and a real example for every steward in the Union.” Zastrow helped build his union during the 1930s and sustain it during World War II. When United Auto Workers Local 248 (CIO) at the West Allis plant of the Allis-Chalmers Corporation wanted to publicize the work of stewards in the CIO News, the union focused on Bill Zastrow as the epitome of a stalwart union man: “rough,” “tough,” and “a 100% union.” As a shop steward in the brass foundry he was a militant, prepared to stop work when necessary to protect his union against incursions by other labor organizations, to take vigorous steps when a foundry worker strayed from the union fold, and to use the grievance/arbitration system to gain new authority on the shop floor.

As the newspaper told its readers, he worked in the foundry for fifteen years, and “many of those years were spent without any union to protect him and the rest of the boys. Bill never forgot what it was to work there without a union. And he never let any of the other guys forget it either.” Zastrow would tell new workers and members waffling on their support of the union “Look it; we got a 100 per cent department here. Every guy is in the union. We made a lot of changes around here with the union and we intend to keep them. We got a lot more work to do. You better join up with the rest of us. We don’t like no hitchhikers in this place.”

For Local 248, “Big Bill” Zastrow represented the ideal union member and steward, always willing to defend the interests of his union and his fellow workers in the face of hostile management. The CIO News told its readers:

He’s always on the job, using the steward’s job and his union grievance structure to protect the men. No matter what goes wrong, Bill is right there to see that justice is done and the men get a fair shake. Wage adjustments, working conditions, a tough foreman—no matter what it may be—Bill wades in, with his 100 per cent department in back of him and the whole union in back of that department.

That’s what convinces the men in the brass foundry. They see the union, through Bill, really doing a job, protecting them every day, fighting for their rights. And they can understand that such things can’t be done unless they stand 100 per cent solid with Bill and the union.1

The struggle was perpetual. Through the first half of the twentieth century, workers at Allis-Chalmers—maker of turbines, electrical generators, pumps, and tractors—fought a never-ending battle for union recognition and protection. If economic issues sparked many disputes, the militancy of individual workers and their unions provided the fuel necessary to do battle with management despite the constraints imposed by wartime unity. The struggle at Allis-Chalmers captured three important elements influencing wartime industrial conflict: the militancy of individual workers, competitive challenges from other unions, and attacks on the union by hostile management. In many other Milwaukee factories during the war, workers engaged in similar struggles to defend their rights and their unions.

Wartime industrial conflict had many faces. It was the challenge to new piece rates; confrontation over work rule interpretation or the foreman’s authority on the shop floor; slowdowns to defend against piece rate speed-ups; strikes to protect wage rates; competition with other unions in jurisdictional disputes; and perpetual organizing in the face of employer unwillingness to recognize the union’s right to exist. At the heart of industrial conflict was the willingness of workers to take direct action in defense of their economic interests and their unions. Worker militancy manifested itself in a variety of ways: individuals and unions engaged in strikes and slowdowns when mechanisms for conflict resolution proved inadequate; unions fought jurisdictional battles when existing unions failed to meet worker needs or when an outside union attempted to displace a recognized bargaining agent; and some unions were forced to engage in a continuous struggle for recognition or existence when faced with hostile and recalcitrant management.

The war united Americans in a common cause, but that unity did not compel them to act in unison nor to drop all other interests and concerns influencing their lives. Workers and unions, managers and companies adapted to wartime conditions. They mobilized, focused their energies, and produced the supplies necessary to fight the war. But they also fought to protect what was best for themselves as workers, unions, managers, and companies. The future world for which everyone fought was being determined not only on the battlefield but also on the shop floor, in the boardroom, and at the conference table.

Wartime industrial conflict stemmed from fundamental concerns of workers and unions, which patriotism and national unity could not supplant. The war did not alter the fact that workers valued and fought for economic security and control over the workplace, nor that unions fought for the interests of their members and for self-preservation against attacks from other unions and from employers. The breach between labor (workers and unions) seeking its own goals and industry (managers and companies) seeking to control the workplace and to maximize profits guaranteed that industrial conflict would continue throughout the war. Industrial peace required a sense of common interest between labor and management. All too often, such a common interest did not exist.

The factory worker of 1940 lived in a complex world of conflicting allegiances. Workers and unions were by no means immune to the feelings of patriotism that stirred the rest of the American people. Work stoppages during November 1941 consumed .24 percent of the available work time but dropped to a mere .07 percent in December. Whereas 271 strikes involving 227,000 workers began in November, only 143 strikes involving 29,000 workers began during December. This sharp decline illustrated the impact of the war upon factory workers and their unions, but it was only the most obvious sign of the urgency and seriousness with which America’s workers viewed the outbreak of the war.2

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Philip Murray and William Green, presidents of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and the American Federation of Labor (AFL), respectively, wasted little time before calling for an end to work stoppages in defense plants. In a national radio address several hours after the United States officially entered the war, Murray said that his members would “do their utmost to defend our country. . . .” A few hours later, Allan S. Haywood, CIO director of organization, reminded another radio audience of the thousands of CIO members serving in the armed forces, and of the millions willingly serving in the production army. In the days that followed, international and local unions alike flooded CIO headquarters with statements of support for the war effort and their commitment to all-out production.

William Green likewise declared the AFL’s support for the war effort, and called for an end to work stoppages in defense plants. The federation’s members clearly supported Green’s response to the Japanese attack. Telegrams and letters streamed into the federation office from union locals and central labor unions throughout the country, pledging support for the war effort.

The leaders of America’s two major labor federations quickly committed their members to abide by a no-strike pledge. They did so with the full knowledge that such a commitment was necessary to preserve the labor movement; but they also understood that the pledge would be difficult to enforce if mechanisms for resolving legitimate grievances failed to work properly or in a timely fashion.3

To foster the kind of cooperative relationship necessary for industrial peace, President Roosevelt called some of the major leaders of labor and business together for a conference on December 17, 1941. The President’s labor-management conference began its deliberations in the hope of formulating a program to assure continuous production during the war. Six representatives of the CIO, six representatives of the AFL, and twelve business executives attended the conference. Although they agreed on a no-strike, no-lockout policy and on the need for a war labor board, the conference deadlocked over the closed shop issue. Organized labor had long argued that industrial peace depended, in part, on union stability. The best way to ensure stability was to guarantee full union membership by requiring, as a provision of the contract, that no one work in the plant without joining the union. Company managers often opposed such provisions on the grounds that they infringed on the individual worker’s right of free association. Business leaders preferred an open shop with no requirement of union membership. The labor delegates also insisted that disputes involving the closed shop should be placed within the labor board’s jurisdiction, but industry delegates feared that decisions by a government agency would rob management of an important prerogative. The industry representatives demanded that existing conditions be frozen and that such disputes be excluded from the board’s supervision.

The President settled the matter by accepting the three points of agreement: the no-strike, no-lockout policy; peaceful settlement of disputes; and creation of a new War Labor Board (WLB) to settle all conflicts that could not be resolved by other means. The labor delegates were pleased with the final outcome, but the industry representatives were shocked. They expected the President to hear their arguments before making such a move. This he had not done.

In these darkest days of the war, when victory was distant and tenuous, representatives of labor and management could not reach an amicable agreement. The industrial members of the conference believed that the open shop was a fundamental principle in a free society. Organized labor, having committed itself to the war effort, viewed WLB jurisdiction over closed shop disputes as essential to union security. Without the strike weapon as a means of defense, the labor representatives looked to government adjudication to protect local unions from destruction at the hands of hostile employers.4

During the defense crisis of 1941, as the United States was preparing for war, strikes reached a level comparable only to the peak years of 1917, 1920, and 1937. CIO and AFL organizing activities, communist militancy prior to the German invasion of Russia, and coal strikes combined to produce 4,288 strikes during 1941. These work stoppages involved 1,860,621 workers and cost industry 28,424,857 man-days of idleness. During the first year of the war, strikes fell by 31 percent, involved 64 percent fewer workers, and cost 82 percent less idleness. In other words, there were fewer strikes, they were short, and they involved a comparatively small number of workers. As workers became increasingly concerned about the rising cost of living and their postwar wage rates, strike activity escalated. By 1944 there were 16 percent more strikes than in 1941, involving almost as many workers. Nonetheless, the war and rapid government intervention contained the strikes to such an extent that they resulted in only 38 percent of the idleness recorded in 1941.5

Unfortunately, as unions increasingly relied upon government for assistance to settle disputes and prevent conflicts from developing into strikes, the agencies to which they turned often proved inadequate for the task. Workers became impatient and disillusioned with WLB delays, with stalled contract negotiations, and with the apparent failure of their wage rates to keep pace with inflation. The rising number of strikes illustrated the frustration they felt. It also demonstrated that workers on the shop floor still sought to control their own destinies, and that union leaders still sought to protect the rights of labor and the power of their organizations. Nonetheless, the strike remained a weapon of last resort to which workers turned when more acceptable means failed to resolve an industrial dispute.

Milwaukee’s unions abided by the no-strike pledge as best as they could, but that pledge was never considered holy writ. Strikes usually were settled quickly by negotiation, conciliation, mediation, or arbitration. When necessary, the leaders of an international union or of the CIO or AFL applied pressure to urge strikers back to their jobs. In Milwaukee, unlike the pattern in locals of the Detroit auto workers and the Akron rubber workers,6 such pressure was seldom applied with enough force to crush a strike. It did not need to be applied in such a manner. The average Milwaukee strike was a short, spontaneous, local affair that neither threatened the war effort nor challenged the authority of the parent union. A strike by one of Milwaukee’s unions may have brought negative publicity to the labor movement and sharp rebukes from union leaders, but a locally focused strike seldom initiated the takeover of a local by a parent union or the ousting of strike leaders by officials with greater power.

In fact, most industrial conflict never entered the public arena in the form of a strike. Instead, it was resolved quietly within the normal collective bargaining and grievance process, or through the aid of a government conflict resolution agency. The Conciliation Service was one of the first agencies likely to be contacted when a dispute reached an impasse, and it assisted in resolving many such conflicts without public strife. When, for example, the Heil Company hired eighteen new employees while thirty-two workers remained on layoff, the Steelworkers’ local cried foul. The case was adjudicated with the aid of the Conciliation Service and the company agreed to pay damages to the aggrieved workers.7 At the Nordberg Manufacturing Company, members of Molders and Foundry Workers Local 125 threatened to walk out if the company did not fire Alex Fedorwicz, who had been involved in several altercations with fellow workers. Company officials refused to take action, claiming that the underlying cause of worker discontent was the fact that Fedorwicz was a “pace setter”—meaning he worked too fast. The Nordberg management would not countenance such efforts to control production and undermine managerial control. Whatever the cause, tempers cooled after a federal conciliator convinced the union to forget the fight that sparked the dispute.8 Workers at Globe-Union, Inc., maker of batteries and switches, fought with the company for over seven months in 1943 and 1944 about piece rates. In disgust, the affected workers undertook a six-week slowdown. Only intercession by a Conciliation Service official prevented a strike.9

When the Conciliation Service could not solve a problem, it often certified the dispute to the WLB for resolution. Many workers saw this process as a bureaucratic mire that led only to endless wrangling. Still, most workers stayed on the job despite endless delays, frustration, and defeat.

The course of a dispute between the AFL Operating Engineers and the United States Rubber Company, operators of the Milwaukee Ordnance Plant, provides an excellent example of a union waiting patiently for a decision and being defeated by delays. During the fall of 1942 the Milwaukee Federated Trades Council (FTC) and the United Rubber Workers of America each launched organizing drives at the newly constructed facility. In April 1943, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) conducted an election in which the workers chose Federal Labor Union 23359 and fourteen AFL craft unions to represent them.10

Immediately, Operating Engineers Local 311 began negotiating a contract to cover powerhouse, sewage treatment, water treatment, and utility workers. Negotiations soon bogged down over questions pertaining to union security, wages, vacations, seniority, and overtime. With the aid of the Conciliation Service, the parties settled their disagreement regarding vacations and overtime, but they could not reach agreement on the other issues. The rubber company refused to force workers to join a union, and the Operating Engineers feared their position as bargaining agent was being jeopardized by disparaging remarks from low-level company officials and by wartime wage controls that made it difficult for the union to act visibly on the workers’ behalf. With these shackles in place, Local 311 worried that existing delinquency in the payment of dues might escalate until the union found itself bargaining for all of the employees under its jurisdiction while only a small portion paid for the service.

The union pointed to numerous examples of inter- and intra-plant inequalities to defend its demand for a ten-cent-an-hour raise. On seniority, the company continued to insist that it needed a six-month probationary period to determine whether an employee was fit for a job. The union proposed a three-month probationary period—two months longer than in most of its other contracts—and insisted that many of the employees under its jurisdiction came to the company already trained and certified with a city stationary engineer’s license.

With these issues unresolved, the case went to the WLB in September 1943. A little over two months later, the regional WLB granted Local 311 a standard maintenance-of-membership clause and a clause specifying a three-month probationary period. The board did not approve the union’s wage demands. It concluded that wages conformed to local practice and that no inter-plant inequality existed. The WLB panel declined to rule on the issue of intra-plant inequalities until after the Wage Administration Agency ruled on an earlier wage application upon which the Operating Engineers’ case was based. In May 1944, well over a year after the union began bargaining, the regional WLB issued a directive order denying any general wage increase. By that time a wage increase was irrelevant; the Milwaukee Ordnance Plant had closed, its services no longer necessary to the war effort. After waiting patiently, the union had failed to get satisfaction on the one issue that would have benefited the workers most directly and that would have demonstrated the value of the union most clearly.11

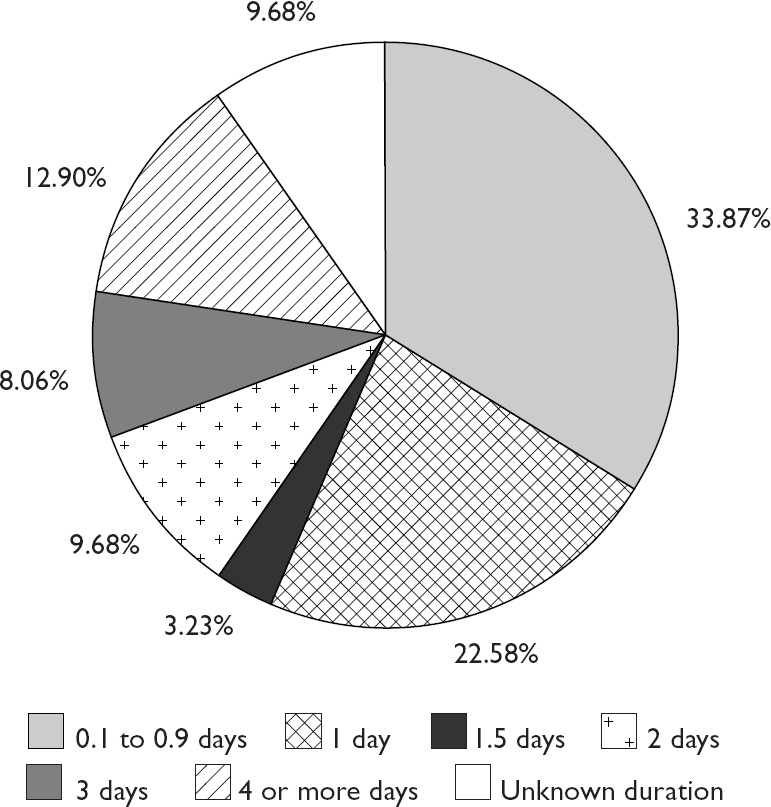

Despite patriotism and the efforts of federal dispute resolution agencies, workers did strike. The Bureau of Labor Statistics identified eighty-eight strikes in Milwaukee between the beginning of 1942 and the end of 1945. Perhaps as many as twenty of these occurred after the war ended. As on the national level, the number of work hours lost due to strikes peaked in 1943 and then declined in 1944 despite a sixfold increase in the number of work stoppages.12 Over half of the sixty-two local strikes that occurred during the war and could be studied in any detail lasted a day or less. (See Graph 1.) Only 13 percent of the strikes lasted longer than three days. This record was a tribute to the patriotism of workers, even when they were on strike, and to union leaders who promptly acted to cajole, persuade, and convince workers to return to their jobs.

GRAPH 1

Duration of Strikes in Milwaukee (December 1941–September1945)

Only eight of the Milwaukee strikes for which the duration could be determined lasted four or more days. The longest strike actually was a prewar conflict. AFL structural steel workers had been on strike since October 1941 protesting use of non-union Works Progress Administration employees on the new National Guard air base at Mitchell Field. The conflict had stopped work on aircraft hangers for the facility. Structural steel workers agreed to return to their jobs on December 18, 1941, after Secretary of War Henry Stimson issued a direct appeal to the workers. The month-long municipal strike of 1943 was the city’s second-longest stoppage. The third-longest strike lasted twelve days. It occurred when workers at William Grede’s Smith Steel Division unsuccessfully tried to end a collective bargaining stalemate with the company’s owner, who fended off union recognition at every turn. Both AFL and CIO unions were represented in the remaining six strikes that lasted four or more days. These disputes involved contract negotiations, grievances, and wage issues.

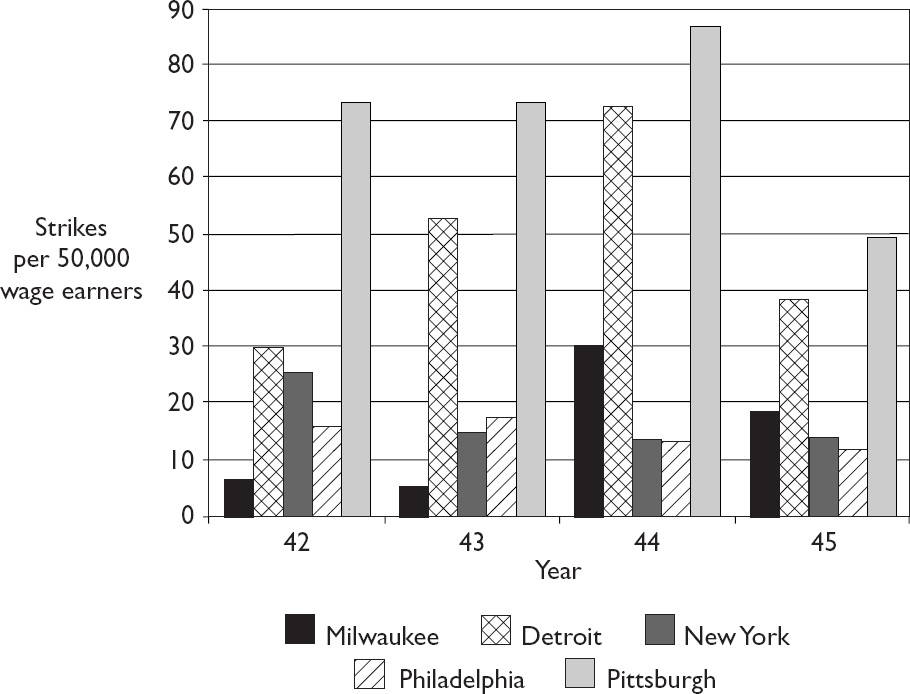

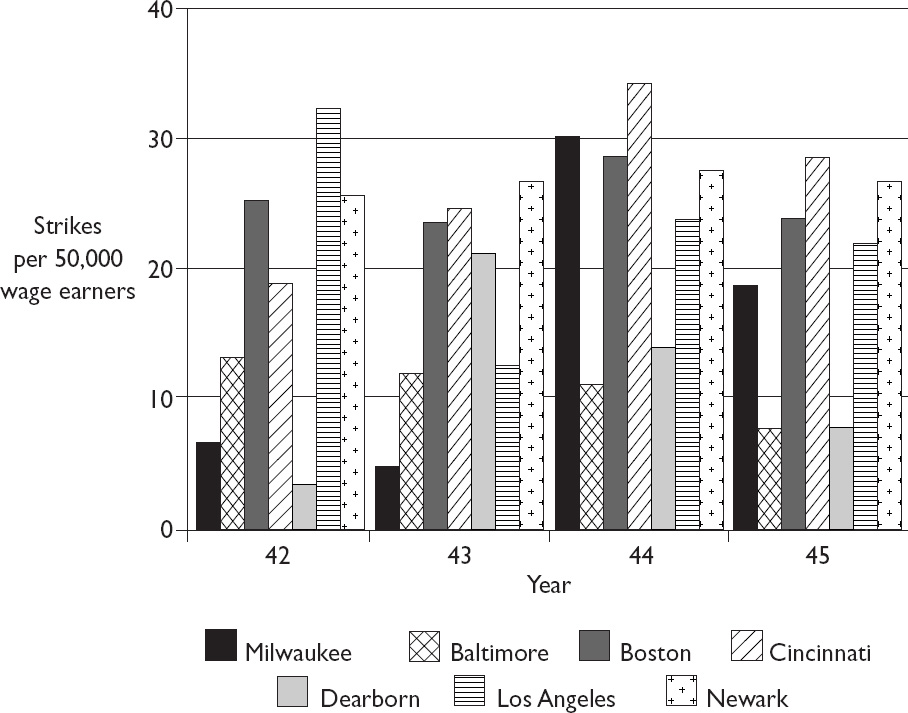

Milwaukee’s strike record was not unusual when compared with the most strike-prone cities in the United States and with cities having a comparable number of wage earners.13 Detroit, New York, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh each had at least fifty strikes a year, according to the BLS. Milwaukee had thirty-seven strikes in 1944, but only eight in 1942 and six in 1943. Of the cities studied for this comparison, only Dearborn (five strikes in 1942) had fewer strikes than Milwaukee during the first two years of the war. When the data are adjusted to eliminate city size as a bias influencing the strike statistics (see Graphs 2 and 3), Milwaukee had thirty strikes per 50,000 wage earners in 1944 and 18.7 strikes per 50,000 wage earners in 1945. This placed the city well behind Detroit and Pittsburgh for those years, but ahead of New York and Philadelphia. Similarly, although Milwaukee had a very low strike rate for 1942 and 1943 when compared with six cities having a comparable number of wage earners (Baltimore, Boston, Cincinnati, Dearborn, Los Angeles, and Newark), it had slightly more strikes per 50,000 wage earners than any of those cities except Cincinnati in 1944 and slightly fewer than four out of the six cities in 1945.

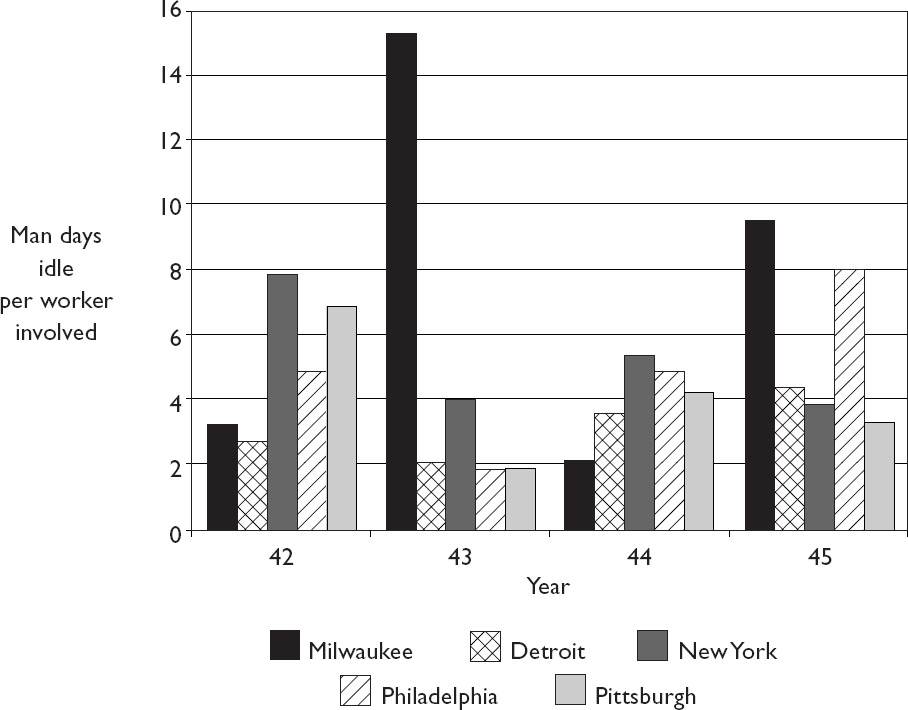

When one measures the severity of strikes by comparing man days idle per worker involved (see Graphs 4 and 5), Milwaukee’s record was both much better and much worse than other cities, depending on the year.

Of the ten cities used for comparison, only Detroit and Dearborn had lower relative levels of strike idleness than Milwaukee in 1942 and none of the ten cities had a lower level in 1944. In contrast, Milwaukee had a higher relative level of idleness than any of the other ten comparison cities in 1943 (when it only had six strikes), and in 1945. Probably because of the protracted municipal dispute in 1943, Milwaukee registered almost twice as much relative idleness as Boston and almost four times as much as Detroit. In 1945, only Philadelphia approximated Milwaukee’s level of strike idleness, although a 192-day postwar strike at Geuder, Paeschke and Frey, a manufacturer of metal and enameled kitchenware, probably skewed Milwaukee’s record.

GRAPH 2

Milwaukee Strike Record Compared to the Record of the Most Strike-Prone Cities (January 1942–September 1945)

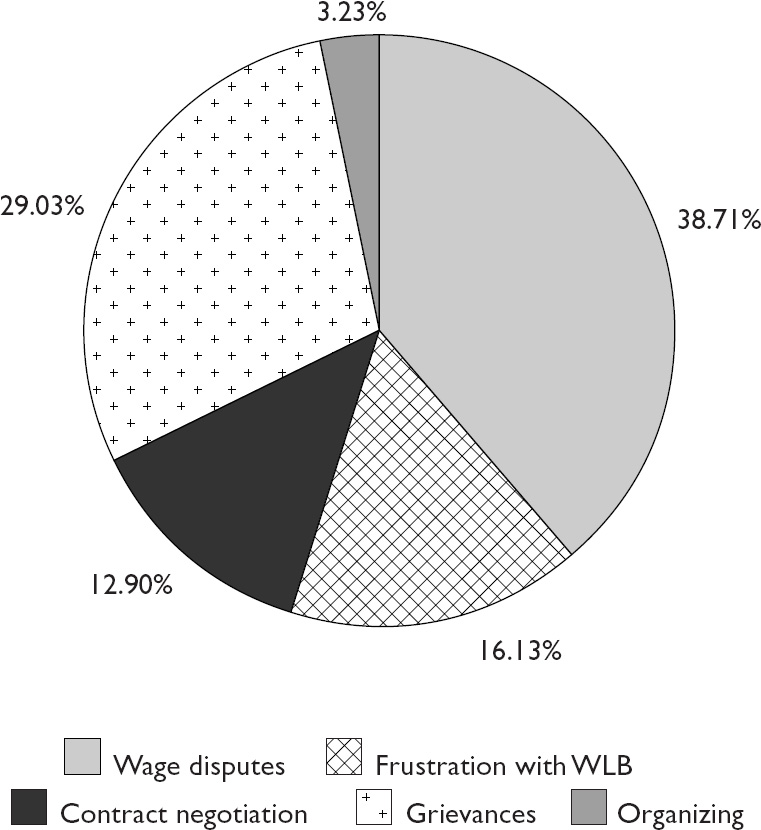

Workers struck when they were left with the choice between walking off the job or capitulating on an issue they perceived to be significant—but only after the normal grievance-and-negotiation process and the government’s conflict-resolution agencies had failed to resolve the dispute. The source of disputes lay within traditional areas of industrial conflict: the preservation of wage scales, the negotiation of contracts, and the handling of grievances.14 (See Graph 6.)

The first two categories accounted for well over half of Milwaukee’s strikes for which causes can be identified. Approximately nineteen (one-third) of the city’s work stoppages involved non-wage grievance issues. Such grievances included, for example, the demand that an employer reinstate a fired worker, that a company transfer an oppressive supervisor, that new work rules undercut established working conditions, that a company failed to process grievances, and that seniority rights had been violated. Few grievance-related strikes involved issues that threatened the existence of the union, but they represented attempts by workers and their unions to maintain control over the workplace.15

GRAPH 3

Milwaukee Strike Record Compared to Cities with Comparable Number of Wage Earners (January 1942–September 1945)

In typical Milwaukee disputes, workers at the Milwaukee Foundry Equipment Company, Harley-Davidson, Geuder, Paeschke and Frey, and Ampco Metal disrupted production over wage issues when wartime conflict resolution systems failed. Simply put, patriotism, union leaders, and government agencies limited the extent to which conflict interfered with production, but economic issues, combined with long settlement delays and wartime tensions, could push workers to take actions to defend their interests, even if those actions had a negative impact on the war effort. At the Milwaukee Foundry Equipment Company workers struck over rate classification despite pressure from the union to return to work immediately. At Harley-Davidson, women workers took a “holiday” in protest over equal pay issues. A protracted dispute over time study and piece rates resulted in at least one slowdown, three short strikes, and numerous smaller disputes between Fabricated Metal Workers Local 19340 (an AFL federal labor union) and Geuder, Paeschke and Frey.

Not all disputes resulted in strikes. The Employees’ Mutual Benefit Association and management at Ampco Metal fought throughout the war over piece rates and production limits. The company fired a steward for usurping a management prerogative when he encouraged a worker to stay within established production limits. In a later case, the union expelled a worker (tantamount to firing the worker because union membership was required for employment at Ampco) for exceeding the company’s production limits and thereby threatening the established piece rates. These disputes were settled only through lengthy arbitration. At their core, all of these disputes revealed the willingness of workers and unions to take direct action in defense of economic interests.

GRAPH 4

Milwaukee Strike Idleness Compared to Idleness in Cities Having Comparable Number of Wage Earners (January 1942–September 1945)

In the summer of 1944, when the CIO auto workers at the Milwaukee Foundry Equipment Company struck to protest an Employment Relations Board ruling that they had engaged in an unfair labor practice, they were really demonstrating their frustration with problems over rate classifications. Under a WLB directive, the rate classification dispute was to have been settled by arbitration, but the company and the union could not agree on the arbitration procedure. The unfair labor practice ruling triggered a spontaneous strike that lasted at least a week despite intervention by Walter Cappel, international representative for the United Auto Workers Union. Beginning on the first day of the strike, Cappel urged the workers to return to their jobs. As the Conciliation Service entered the case, it was clear that the quasi-judicial mechanisms for handling disputes had broken down and that the workers had taken matters into their own hands to force a resolution of the problem.16

GRAPH 5

Milwaukee Strike Idleness Compared to Idleness in the Most Strike-Prone Cities (January 1942–September 1945)

Women in the prepacking department at the Harley-Davidson Motor Company (members of AFL auto workers Local 209) demonstrated a similar willingness to force the resolution of a nagging wage problem by refusing to work. In November of 1943 the Conciliation Service came to the plant to settle a dispute involving women in Department 19. Harley-Davidson had formed Department 19 to dip motorcycle parts in wax (to protect them against corrosion) and then pack the parts for shipment overseas. The company previously limited packing and shipping work to men in a different department; the new department was staffed entirely with women. In a move designed to protect male positions from being undercut by the newly hired female workers,17 the union demanded equal pay for the women in Department 19, as well as improvements in the base rate for women workers. Union officials contended that women packers did work equal to that of their male counterparts or, in the case of the waxing operation, more difficult than the work expected of men. The starting rate for men at Harley-Davidson was 79 cents an hour. Women earned an hourly starting rate of only 55 cents with raises of 2.5 cents an hour every three months for a year. A woman with one year’s service earned 65 cents an hour. Based on this scale, women in Department 19 worked within a rate range of 55 cents to 65 cents an hour in November 1943.

GRAPH 6

Causes of Strikes in Milwaukee (December 1941–September 1945)

Despite the semblance of demanding equal pay, the union actually demanded only an increase in the base rate of 10 cents an hour for women in Department 19, which would have boosted the lowest-paid women to 65 cents an hour. A woman earning 65 cents an hour prior to the raise would earn 75 cents an hour after the raise. In effect, this process would create a new range for women in Department 19 of 65 cents to 75 cents an hour. The Conciliation Service arranged a compromise with the company that left the base rate at 55 cents an hour but accelerated the schedule for raises so that the women reached 66 cents an hour after only three months. After evaluating the work being done in the department, Harley-Davidson also agreed to a new rate range of 66 to 79 cents an hour. The compromise was forwarded to the WLB for approval.

Seven months later, the board finally issued its ruling, granting a rate range of 65 to 78 cents an hour—but without making an adjustment in the existing process that brought new women workers to 65 cents an hour after four 2.5-cent increases. With approval in hand, the company and the union disagreed over how to implement the new rate range. In stark contrast to the agreement worked out by the Conciliation Service the previous fall, the company now insisted that the WLB had approved only the new rate range but had not approved any increases above the minimum of 65 cents an hour. The company maintained that all women workers in Department 19 should be placed at 65 cents an hour regardless of their previous rate, and that subsequent raises should be based on merit. The union contended that the WLB ruling allowed a 10-cent raise, placing the women within the rate range in keeping with their previous position. This interpretation meant that the highest-paid women in Department 19 should receive 75 cents an hour. The union agreed that the remaining 3 cents an hour (bringing a worker to the top of the range of 78 cents) could be reserved for merit increases.

Faced with further delays, the women in Department 19 wanted to strike. They stayed on the job on June 6, 1944, only at the behest of the union bargaining committee, which spent the day in discussions with management officials. That evening, despite the welcome news that the Allies had landed in Normandy, the bargaining committee decided to call a “work holiday” for the following day. Technically this “holiday” was not a strike. Under an unusual contract clause, the union could call a one-day work stoppage in the event of a serious controversy with the company; but the “holiday” did not have the same force as a strike. As Leonard Hackert, president of the union, told a reporter:

We told the men, when they reported to work Wednesday morning, that no one had to stay out of the plant. We said the women were determined not to go to work until something was done about the rates and the others could do what they wanted to about it. They decided on their own not to work.

The workers went back to their jobs the following day, after Harley-Davidson agreed to grant an immediate 5-cent raise to workers in Department 19 (bringing workers at 55 cents up to 60 cents an hour, workers at 62 cents up to 67 cents, and so forth), with additional raises to await approval of the WLB. The WLB settled the issue the day after the June 7 “holiday” by accepting Local 209’s interpretation. The 125 women in Department 19 received the full 10-cents raise negotiated in November of 1943, maintaining the old rate relationships between women in the department and reserving the remaining 3 cents for merit raises.

In a sense, the union sanctioned this job action by calling a “work holiday,” but it was the militancy of the women of the prepacking department whose refusal to work brought the conflict to a head. For these women, the issue of the dispute was economic justice. For the union and the company, however, another set of issues took precedence. The company insisted on implementing the new rates in a manner that would have based future raises within a given rate schedule upon the subjective judgment of management as to the merit of the employees involved. Such a system would have made it difficult for workers to judge the fairness of raises and, from their perspective, could be viewed as a move toward greater management control of the workplace. In contrast, the union advocated maintaining a system based on seniority, a system that could be judged objectively, as well as a system that would have maintained existing differences between workers.18

A work stoppage could be brought on by a dispute over wages, contract interpretation and negotiation, or concern for a mistreated worker. Nonetheless, the causes of any particular strike often lay as much with the cumulative effect of several events as with any one incident. The history of industrial relations at Geuder, Paeschke and Frey typified the complex forces acting upon Milwaukee workers who struck during World War II.

Members of Fabricated Metal Workers Local 19340 struck in May 1944 to protest production standards that were set so high that inexperienced employees working on piece rate received less than the minimum wage set by the contract.19 Behind this event was a history of conflict over time study methods and piece rates. Relations between the company and the union seemed cordial during the defense crisis, and the company frequently sought the union’s “advice, consent and suggestions on matters pertaining to defense work.”20 The relationship soured in the spring of 1942 when company managers refused to discuss several grievances and walked out of a meeting with union representatives. As Walter Norbeck, business representative for Local 19340, told William Green, relations had become “very strained.” The existing wage agreement failed to establish clearly the accepted piece rates for many operations and resulted in numerous disagreements between company and union officials. After intervening, AFL organizer David Sigman optimistically reported to William Green that the problem would be resolved in the new contract currently being negotiated.21

Unfortunately, Sigman’s optimism was premature. Contract negotiations deadlocked in June and the union requested assistance from the Conciliation Service. When conciliator R. G. MacDonald took the case, he found both sides intransigent. The union continued to demand a wage increase while the company insisted that such a raise would force it to reduce the labor force to 25 percent of its normal level. After a month and a half of further negotiations, both parties accepted MacDonald’s suggestion and referred the matter to an arbitrator. Two months later, in September, the arbitrator ruled that a raise of 3.5 cents an hour was in order because of inflation. He also suggested that two union-management committees be established to study and fix piece rates and to study improvement of working conditions. Both parties accepted the pay increase, but the company balked at the precedent of joint union-management decision-making regarding piece rates and working conditions. This portion of the arbitrator’s recommendations struck at managerial control over the work-place, and the company would not yield on this issue of joint committees.22

At the same time, workers at Geuder, Paeschke and Frey remained discontented over piece rates. They often complained that rates set by the company were too “tight” and that delays in meeting requests for the retiming of jobs were demoralizing the work force. When the company changed the production methods used to produce baking pans for the quartermaster corps, the workers deliberately cut production in half. R. G. MacDonald was called to end the slowdown and obtained an agreement between the company and the union to accept the findings of a Conciliation Service expert who would set a fair piece rate for the operation. However, before the Conciliation Service technician reported, the two parties negotiated a mutually acceptable piece rate in March 1943.23

The negotiating skills that brought an agreement in March failed to resolve other general concerns over piece work rates and worker participation in time studies. After an arbitrator settled another rate dispute in August, the union decided to take matters into its own hands. It was clear that workers at Geuder, Paeschke and Frey did not trust management to conduct fair time studies. They wanted to participate in the process of timing jobs and in the establishment of bonuses for day-rate employees who assisted piece workers. Based on the assumption that “a knowledge of time-study would assure fair time and rate schedules by the company,” Fabricated Metal Workers Local 19340 organized a series of time-study classes for its members.24

Rate disputes seemed to abate for a time, but the old conflict arose again in May 1944, when the company renewed production of twenty-five-pound lead kegs after a lapse of many months. The rate for the job was to be the same as when the kegs were produced earlier. The union protested that the old rate was set using experienced workers and that the current, less experienced work force would not be able to produce at the same rate. The company made two adjustments, which the Fabricated Metal Workers felt were inadequate; but management refused to change the rate further. In protest, the workers cut production to almost nothing, and Geuder, Paeschke and Frey retaliated by implementing a policy of paying piece workers only for the material they actually produced without regard for the minimum hourly pay set by the contract. Tensions already were high in the plant due to a series of unresolved grievances, and when several workers received only $19.06 for a forty-eight-hour week, employees in the paint pail department spontaneously quit work. The work stoppage quickly spread to the rest of the plant. The one-day strike ended when Major James P. Holmes, a federal conciliator, negotiated an arrangement whereby

The Union General Committee agreed to co-operate in securing productive capacity on disputed piece rate jobs at least sufficient to enable the employees to earn the minimum rates, or more, and to continue such cooperation even where the Company pursued the new policy of paying only what the employee actually earned, but reserving the right to carry the matter through the Grievance Procedure.

It was a pragmatic solution. The company got a promise from the union to help maintain production, but with no benchmark against which to measure that cooperation. The union accepted the possibility that the company might pay workers on a slowdown only for the work actually done. Nonetheless, the union reserved the right to grieve such actions and thereby refused to sanction the company’s right to cut pay unilaterally.25

The solution settled the precise cause of the strike, but it did little to ease the hard feelings that had developed between the company and its work force. Two other strikes occurred at Geuder, Paeschke and Frey as the war drew to a close; both were quite predictable, given past events. As Germany collapsed, employees in one department spontaneously started an unauthorized strike to protest several disciplinary discharges that appeared to be part of a calculated effort by the company to remove “troublesome” employees. The walkout quickly spread through the plant. On several earlier occasions the company had fired workers under circumstances the union found unacceptable. In one case, management even refused to divulge the precise charges or the source of their information. In another case, the company took disciplinary action against a woman who had allegedly led a one-hour sitdown strike. In each of these situations, the union found itself forced to take the issues to an arbitrator. The new firings in 1945 fit an established pattern, and the workers had had enough of delays and legalistic solutions.26

Similarly, almost immediately after the war ended, the Fabricated Metal Workers union began a 192-day strike as they sought an acceptable contract with the company. The pattern was all too familiar. Earlier contract negotiation disputes had been resolved through arbitration or the WLB. The 1942–1943 contract expired on June 30, 1943. Union and company representatives began negotiating the new contract on June 11 but came to no agreement. Negotiations remained at an impasse even after Maj. Holmes of the Conciliation Service met with the parties several times in July, and the dispute was certified to the WLB.

When the WLB panel reported in November 1943, it was clear that the establishment of piece rates and union participation in time studies remained the major stumbling blocks obstructing the negotiations. Taking full advantage of its control over information, the company steadfastly refused to provide the union with the formulas used to set rates. Management officials also argued that the time study process was too complicated for the union to be able to supply an individual competent enough to participate in the process. Perhaps because they feared the loss of managerial control, the company had no intention of providing their union opponents with information on piece-rate formulas and time-study methods, the two most significant sources of worker discontent at Geuder, Paeschke and Frey. The WLB panel failed to solve these basic issues of conflict and the dispute was still unresolved a year after the 1942–1943 contract ran out. In trying to bring the conflict to an end, H. Herman Rauch, an arbitrator from the Wisconsin Industrial Commission, clearly stated the problem and outlined its impact on the company’s workers. He lectured the company:

One of the major complaints voiced by the Union related to the current vagueness of the expected earning rates of piece workers. There is no way of telling when an employee on a particular job is achieving what can reasonably be expected from such operation. The Union had no knowledge and does not seem to be able to find out with any degree of accuracy how the Company reaches its conclusions on the matter. . . . The lack of proper information on so vital a point caused suspicion and discontent. Consequently, grievances on rates have been abnormally numerous and bitter. . . .

There can be no doubt that the Union and each employee have a right to know precisely what wage rate applies and how it is determined. Such knowledge is indispensable in the case of an incentive system where the “will to work” is the key to increased production.27

With a certain sense of exasperation, Herman Rauch returned to this case in October of 1944 and helped the parties negotiate an interim rate schedule that could be used to determine the back pay due workers under the 1943–1944 contract, for which negotiations were still underway. Ironically, that contract had expired on June 30, 1944. With the new rate schedule in hand, the old contract was finally completed, and negotiations began on the contract for 1944–1945.28

This new round of negotiations immediately bogged down as the parties argued, in the words of conciliator J. J. O’Brien, over “practically every sentence of the contract.” The dispute went to the WLB for settlement, where it remained when the contract officially ran out at the end of June 1945.29

With the 1944–1945 contract dispute awaiting settlement by the WLB, negotiations on the 1945–1946 contract stalled, once again, on virtually every major issue. The workers were fed up with delays in negotiations, an accumulation of unresolved grievances, and the company’s failure to implement both an equal pay for equal work clause from the 1943–1944 contract and the interim piece-rate schedule that had been negotiated with the help of Herman Rauch in October 1944. As the United States made final preparations for the atomic bombing of Japan, the frustrated workers at Geuder, Paeschke and Frey requested a strike vote as required by the Smith-Connally Act. William Green immediately informed the local that the AFL would not sanction a strike as long as the nation was still at war, and he urged the union to abide by the no-strike pledge.

Soon after the Japanese capitulated in September 1945, the union asked again for AFL support. Green instructed Jacob F. Friedrick, the AFL organizer in Milwaukee, to try to resolve the conflict. Friedrick found negotiations blocked by company officials unwilling to compromise on any of the issues in dispute. On September 8 the NLRB conducted a strike vote. The workers voted 350 to 23 in favor of a work stoppage. After another round of fruitless negotiations, the membership again voted to stop work. Thus, after a long prologue, one of Milwaukee’s first and most protracted postwar strikes began on September 12, 1945.30

In contrast to the impression often given by the daily press in its coverage of strikes, Local 19340 was not a power-hungry organization hell-bent on dominating either the metalworkers or the company. The strikes stemmed from the union’s and the workers’ desire to protect wage rates from being undercut by the company, from the desire to protect employees from discriminatory firings, and from the frustrations of wartime industrial relations. The strikes that occurred during the war need never have happened. There existed governmental machinery to settle all such disputes; but that machinery never worked perfectly. It could not always relieve pent-up worker frustration, nor did it always work swiftly. When the workers at Geuder, Paeschke and Frey engaged in a slowdown or went on strike, it was not because of caprice. Such actions represented an institutional response by the union to the need to protect the rights of its members, and a personal response by workers as they tried to exert control over their lives and futures. The years of conflicts and of delays took their toll. Agreements had not been kept, expectations had not been met, grievances had not been resolved, negotiations had been stalled, and disputes had festered over time-study methods and the setting of piece rates. Slowdowns and strikes remained weapons of last resort, but they were weapons that workers were willing to use when the quasi-judicial conflict-resolution system failed.

At a company like Ampco Metal, Inc., conflict with management over economic issues could lead workers to take direct action to protect themselves. During the prewar and early war years the Ampco Metal company and the Employees’ Mutual Benefit Association, an independent union, had maintained a good-faith relationship. Disagreements sometimes occurred, as they did in any industrial setting, but they were handled routinely through the grievance procedure. For example, on one occasion in 1943, the company and union submitted four grievances to the Wisconsin Employment Relations Board. Before the board could act on two of these disputes, both dealing with claims for back pay, the parties reached settlements. The other two cases dealt with a worker discharge and with the payment of the third shift premium to employees starting work at 4:00 in the afternoon, both of which the arbitrator settled in the union’s favor. Another case in 1943 nullified the closed-shop clause in the Ampco contract because it had never been ratified by the workers as required by Wisconsin law. A referendum shortly thereafter fulfilled the legal requirement, and the closed shop clause could once again be enforced by the union and the company. If anything, these arbitration cases demonstrated to the union that it was secure and that it could deal with Ampco on a reasonable basis.31

But during 1944, this good-faith relationship degenerated into one of distrust. The union feared that the company was trying to cut the piece rate, and the company charged the union with an organized attempt to limit production. Management officials made several technological changes in production equipment and methods during 1944 and, as a consequence, they retimed some of the jobs in the plant in order “to maintain the relationship between earnings and effort.”32 These changes smacked of a wage cut to the workers at Ampco and gave way to the fear that once workers reached a certain unspecified income level, the company would retime the job and review the rate. The employees’ discontent with this situation boiled to the surface when a steward, Edward Mesarich, was fired for threatening a worker with suspension from the union unless that worker stayed within the company’s established production limits. Under the closed-shop clause, suspension from the union would have forced the company to fire the hardworking employee.

Although the employee in question charged that Mesarich had told him specifically to hold down production because his performance was detrimental to the other workers in the department, the Employees’ Mutual Benefit Association argued that the steward was defending the company’s own limits. Far from doing anything disruptive, the union argued, Mesarich had simply warned Albert Vail to operate within established machine speed and feed rates set by the time study or risk company discipline for abusing his machine. Rather than try to prove its charges against Mesarich in the hearing, the company discharged the steward for usurping a function of management—something Ampco could not countenance. Its employees had to know that they answered to company supervisors and not to union stewards. As one might expect given the company’s defense, the arbitrator concluded that Ampco had not proven its case against Mesarich and reinstated the steward. Nonetheless, as a warning to other workers who might try to limit production, the arbitrator refused to grant Mesarich any back pay for the time he was without work.33

Despite the arbitrator’s admonition, the Mesarich case did little to settle the larger piece-rate dispute between Ampco and the employee association. In December 1944 the union expelled Leroy Gilbertson for behavior unbecoming a union member. He had ignored direct instructions from the union to abide by established production standards designed to protect the quality of production and the maintenance of machinery. As Gilbertson stated at the arbitration hearing, he believed he had been moved from the first to the second shift because of union favoritism for another employee, and he therefore had set out consciously to break the established production ceiling. When the union warned him that he was breaking the ceiling in violation of the contract, Gilbertson informed the union board that he had no intention of abiding by the ceiling agreement, that he did not like the union, and that he had no confidence in what it could do. Thus challenged, the union board believed it had no alternative but to expel Gilbertson.

Ampco immediately charged that the union was attempting to limit production and refused to fire Gilbertson. Ampco officials took a much more aggressive stance than in the Mesarich case and told the arbitrator, “The union expelled Gilbertson because it deems limited production by the employees to be necessary to ‘the general welfare of fellow workers, or to the Union as a whole.’ ” Such an attitude violated the letter and the spirit of the contract, the company argued, and it delivered a poignant warning:

Think of the effect upon a worker in any all-union shop plant if he should learn that even in war time, and with the country crying out for more and more production of war products, in light of the acute manpower shortage of which the country is so painfully aware, his refusal to arbitrarily limit his production will bring about expulsion from the Union and loss of his job.34

The union’s defense clearly outlined the origins of the employees’ fear that any extra production would result in an immediate retiming of a job with an accompanying reduction in the piece rate. Near the end of 1943 the company restudied propeller cone production, on which Gilbertson worked, and proposed cutting the rate from 14 cents to 11 cents. The union argued that some workers were neglecting their machines and tools, causing numerous production delays for workers on following shifts, and that average production never exceeded eighty-six cones per operator per eight-hour shift. When the company proposed to cut the piece rate, all of its operators applied for transfers to other jobs. In January 1944 the company and the union came to an agreement specifically designed to increase production. The rate was frozen at 14 cents and a production ceiling of ninety-five pieces per eight-hour shift was set for the duration of the war. Almost immediately morale improved and production soon reached the ceiling level. The company responded by proposing a new ceiling of 105 pieces; but the union refused to raise the ceiling in the belief that the change would only bring a return to old work patterns.

In another arrangement designed to increase production, the two parties agreed that when a worker developed a way to improve production, the benefit would be split in half between the company and the workers, resulting in faster, more profitable production for Ampco and higher wages for workers on that operation. After receiving WLB approval for this agreement, however, the company decided that it had given up too much and convinced the labor board to rescind its sanction, a move that convinced the union that Ampco was no longer prepared to deal with its workers in good faith.

The Gilbertson case only heightened the union’s concern. Ampco’s refusal to fire Gilbertson, combined with repeated changes in piece rates elsewhere in the plant, served to promote the kind of production limits the company wanted to avoid. The company’s time-study engineer openly admitted that high earnings on the part of an operator were a “red light” indicating to the management that the job needed retiming—hardly an attitude designed to instill confidence or good feelings among the workers. The Employees’ Mutual Benefit Association summarized its views when it told the arbitrators,

The Company seems incapable of comprehending that the fear of piece rate cuts on the part of operators is to blame for production hold-backs. The Union is just as anxious as the Company to eliminate this fear and open the way to unrestricted production. Both the Company and the operators would profit from it. The Union, however, is powerless so long as the Company adheres to its present piece rate policy.35

The arbitration board upheld the company’s refusal to fire Gilbertson on the grounds that expulsion by the union constituted an attempt to prevent individuals from performing to the best of their ability as stipulated in the contract. In an attached explanatory opinion, L. E. Gooding, chairman of the arbitration board, questioned why the union took the most severe action available instead of filing a grievance asking the company to discipline Gilbertson for violating the ceiling. Although he refused to blame the company for the workers’ fear of wage cuts, Gooding acknowledged that such fears existed and that the company acted in an “underhanded” manner when it withdrew from the piece-rate compromise after WLB approval. He concluded by urging the parties to return to their earlier good-faith relationship.36

That good-faith relationship had succumbed to the traditional industrial conflict between management’s desire to produce as efficiently and cheaply as possible and the workers’ desire to protect their wage rates. When the company retimed jobs, it reinforced the workers’ fear that they would be working harder and earning less. Members of the Employees’ Mutual Benefit Association took direct action to protect themselves and to enforce limits on production. The war effort—encompassing patriotism, self-sacrifice, and good will—became a secondary consideration in this conflict.

It would be difficult to overestimate the significance of wage-related issues in labor-management conflict during World War II. Nonetheless, issues related to union security also influenced industrial relations as unions sought to protect themselves from company interference and from attacks by other unions. Many government agencies dealt with labor relations issues, but a local union could not afford to allow these agencies to replace the collective bargaining process. Neither the Conciliation Service, the WLB, nor the NLRB were likely to play a significant role in a conflict unless a deadlock had already been reached. Long before that time, most disputes were resolved through the normal functioning of the collective bargaining system. When a dispute could not be solved quietly, government agencies tried to protect the rights of each party under the law and to mediate or impose a solution without an interruption of production. These activities ultimately gave meaning to labor legislation that had recognized organized labor’s right to exist; but the local union still bore the responsibility for ensuring that the company followed the contract, that workers’ rights were not violated, and that members continued in good standing.

Measures such as the WLB’s maintenance-of-membership awards could protect a union from direct attacks, but the WLB could not stop conflicts that arose out of the workers’ desire to be represented by another bargaining agent or the unions’ desire to expand its membership through organizing. The WLB and similar conflict-resolution agencies created a quasi-judicial setting within which unions could operate, but they did not replace the need of workers and unions to protect their own interests.

Jurisdictional disputes, which the Milwaukee press portrayed to the public as irrational squabbles, often developed out of such needs. They marked one of the boundaries beyond which organized labor would not go in the name of the war effort. American corporations continued to advertise, seek new markets, and develop new products for the postwar era. Similarly, unions refused to stand idle while competing organizations raided their membership and stripped them of their power. The principal distinction between corporations—which funneled resources into maintaining a share of the market—and unions—which continued to organize—was that union competition frequently caused noisy, visible, public conflict, while corporate competition did not. Just as companies saw no reason to stagnate or cease competing with their rivals in the marketplace, unions continued to attract new members and to fend off challenges from other unions. The NLRB conducted approximately 3,762 certification elections and cross-checks during the war years. Over half the disputes that came to the Board’s attention were direct confrontations between unions of the rival labor federations. Most such disputes were settled through the normal functioning of the NLRB, resulting in little or no lost work time.37

Jurisdictional conflicts in Milwaukee consisted almost exclusively of fights between two or more AFL international unions or between an international affiliated with the AFL and an international affiliated with the CIO. The Milwaukee CIO, dominated by the auto and steel unions, suffered relatively little from internal strife. Disputes arose from the basic right of workers to be represented by the union of their choice and from the refusal of unions to give up the right to organize during the war.

Thus, when the Firemen and Oilers union tried to raid members of the Pulp and Sulphite local at Hummel and Downing, the paper union fought back. Struggles between the AFL and CIO Auto Workers at Wisconsin Motor Corporation; between the Amalgamated Clothing Workers (CIO) and the United Leather Workers (AFL) at J. Laskin and Sons; and between the Operating Engineers (AFL), the Brotherhood of Firemen and Oilers (AFL), and the United Auto Workers (CIO) at Seaman Body all reflected ongoing competition between unions, as well as the willingness of workers to defend their unions or shift allegiance when necessary to protect their interests.

The Wisconsin Employment Relations Board upheld the right to be represented by a union of one’s choice when, in 1944, it ordered an election at the Hummel and Downing Company, a paper manufacturer. For many years the International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite and Paper Mill Workers represented the paper company’s carpenters, millwrights, pipe fitters, machinists, electricians, welders, and plant oilers, but these maintenance employees had become disillusioned because their wage rates had fallen behind those of metal workers in war plants. As a consequence, Local 125 of the Firemen and Oilers union petitioned the Employment Relations Board to order an election so that the maintenance workers could decide whether to form a separate bargaining unit.

When the board held a hearing on the petition, the Pulp and Sulphite union’s principal organizer in Milwaukee, Valeria Brodzinski, argued that the Firemen and Oilers had no jurisdiction over the Hummel and Downing maintenance employees. Pulp and Sulphite locals all over Wisconsin had represented maintenance workers for many years, and, in Brodzinski’s opinion, establishing a separate bargaining unit would only create disunity and hamper production. In response, the Firemen and Oilers’ representative maintained that no jurisdictional dispute existed, that this was simply a case of disgruntled workers who wished to form their own bargaining unit.

After the hearing, the Wisconsin Employment Relations Board ruled that the state employment peace act protected the right of employees “having common interests” to “determine for themselves whether they desired to constitute themselves a collective bargaining unit. . . .” The legislature felt this right was basic enough that it stripped the board of discretion when ruling on such cases. It was a matter for the employees to decide, and the board thereupon ordered an election. The Firemen and Oilers union won by a landslide.38

The Employment Relations Board believed that the workers had a basic right to decide whether they should be represented by the Pulp, Sulphite and Paper Mill Workers union or by Local 125 of the Firemen and Oilers union. Likewise, the workers themselves believed they were being served poorly by the existing local and that they had a right to choose a different bargaining agent. The Firemen and Oilers agreed. For the Pulp and Sulphite union, the employment board’s decision and the results of the subsequent election constituted a dangerous precedent. The union could not be expected to greet the loss of forty-six employees at Hummel and Downing with enthusiasm, nor could it be expected to accept passively this threat to its jurisdiction. If the Hummel and Downing case developed into a trend, the Pulp, Sulphite and Paper Mill Workers union stood to lose members in locals all over Wisconsin.

Conflicts between unions affiliated with the AFL and those allied with the CIO underscored the clash of organizational goals behind many jurisdictional disputes. When George Kiebler, regional director for the UAW-AFL, realized that the CIO auto workers’ union was trying to take over Local 283 at the Wisconsin Motor Corporation, he moved quickly to investigate. What he found was a local being wooed by promises of higher wages and local officials who showed no interest in combating the CIO raid. With authorization from the international he suspended all of Local 283’s officers, took over as temporary administrator, and appointed a forty-member committee to run the local pending a trial of the officers.

However, while Kiebler complained about the raid, officials for the United Automobile, Aircraft and Agricultural Implement Workers union argued that they had simply responded to an internal movement initiated by the members of Local 283. The takeover bid received little or no opposition from within the local. Despite Kiebler’s drastic action and the arrival of an organizer sent by the international, the battle was lost. The CIO already had the allegiance of over half the local’s 700 members. Five days after Kiebler suspended the officers of Local 283, they held a meeting at which the 376 attendees voted unanimously to affiliate with the CIO. By that time, as many as 500 employees of the Wisconsin Motor Corporation may have signed cards indicating their preference for the CIO, and in March of 1943 the local formally affiliated with the United Automobile, Aircraft and Agricultural Implement Workers of America.39

Workers clearly were willing to act on their own behalf when their union failed to act in a manner they found acceptable. Fed up with delays in negotiations on their demand for higher pay, workers at the J. Laskin and Sons tannery struck just five and a half months after America entered the war. The job action was one of Milwaukee’s first wartime strikes, and the leadership of the CIO Amalgamated Clothing Workers’ (ACW) union moved swiftly to make good on its no-strike pledge. As A. G. Piepenhagen, manager of the Milwaukee joint board of the ACW, told reporters,

They got a little excited . . . and took things in their own hands. But the union made them go back. We not only have a contract which does not permit walkouts of this sort but the plant is working 100% on war production. I told them they would have to go back. It’s just a matter of getting together.40

The Laskin workers “took things in their own hands” again one year later when they voted to leave the CIO union and affiliate with the AFL United Leather Workers’ union. They were displeased because the ACW joint board had renewed the union’s closed-shop contract with the tannery despite objections from the local’s leaders. When the company complied with a request from the ACW joint board to fire seven leaders of the new AFL local, five of whom were leaders of the old ACW local, the Laskin workers struck a second time.

Despite pleas by the fired workers, the strikers stayed away from work for three days until the WLB promised to adjudicate the case. Members of the Leather Workers’ union voted to contribute an hour’s pay a week to support their fired leaders while the case was pending before the WLB. A month after the strike, the NLRB held an election in the tannery and the workers voted 319 to 59 to join the AFL. The company soon rehired the fired employees.41

Local 815 of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) was considerably more successful at smashing a CIO threat. The dispute began when two longshoremen openly began organizing for the CIO. At a special meeting on March 30, 1942, members voted overwhelmingly to expel the local’s vice-president, a member of the executive board, and five other members for disloyalty to the ILA and for attempting to disrupt the local. The members reaffirmed this decision a month later after holding a formal trial. In the weeks that followed, the local purged itself of members who expressed sympathy with the CIO, disrupted union meetings, or held “communistic” views. Apparently, the local’s vice-president was considered a member of this faction because he too was expelled although no evidence indicated a tie with the CIO. Instead, he was removed for failing to give due regard to the union, for using obscene language when dealing with employers, for promoting slowdowns, and for obstructing work. Because, in this instance, the local moved quickly to protect itself and to eliminate all of the visible CIO sympathizers, no formal jurisdictional dispute developed.42

A formal dispute did arise, however, when Local 311 of the Operating Engineers sought to establish a separate bargaining unit for powerhouse workers at the Seaman Body plant where UAW-CIO Local 75 had exclusive bargaining rights. Ultimately, three unions (the International Brotherhood of Firemen and Oilers also sought bargaining rights) became locked in combat over nine workers.

The Operating Engineers and Local 75 of the auto workers fought a similar battle prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor. In that case, the powerhouse workers voted unanimously for the auto workers’ union. Ten months later Werner Schaefer, business agent for Engineers Local 311, again requested that his union be allowed to negotiate on behalf of the boiler room employees, many of whom already belonged to the local. Officials at Nash-Kelvinator Corporation, parent company for the Seaman Body plant, indicated their willingness to negotiate, but requested that the Operating Engineers seek NLRB recognition for these workers as a separate bargaining unit to avoid a violation of the CIO’s exclusive bargaining rights in the plant. Shortly after the NLRB ordered an election, the International Brotherhood of Fireman and Oilers, with whom the Operating Engineers had a long-standing jurisdictional feud, also requested recognition, and was placed on the ballot. Thus the dispute developed into a classic conflict between the two labor federations and between two AFL unions, although the Firemen and Oilers seemed to be a minor third party in the conflict.

Warren Schaefer perceived the election as an opportunity for the AFL to strike a major blow against the rebellious CIO. As he told one of his supporters, “This case is quite important in our opinion because if we can win, it will be the first plant in which we have been able to win against the CIO in an election.” Schaefer knew that his union did not hold a majority in the powerhouse when the election campaign began, and he relied upon existing friends and members of the Operating Engineers who were already employed by Seaman Body to establish enough support for the Operating Engineers to win the election. Ultimately the election drive failed, and UAW-CIO Local 75 maintained control over the nine powerhouse workers by a five-to-four vote.43

Jurisdictional disputes represented a competitive challenge that unions could not ignore. Similarly, there remained too many signs of business hostility for labor to relax its organizing activity. National figures such as Thurman Arnold, Eddie Rickenbacker, and Admiral Emory S. Land criticized labor’s disloyalty to the war effort, its greedy pursuit of wage increases, its violation of the no-strike pledge, and its illegal tactics.44 In Milwaukee, the daily papers focused on labor’s faults and called for legislation to curb labor’s supposed abuses of power. The National Small Business Men’s Association sent letters to Milwaukee employers soliciting membership in the organization and attacking the Wagner Act (which placed the authority of the federal government behind unionization), the forty-hour week, and the closed shop. The Milwaukee Association of Commerce urged its members to lobby for the Smith Labor Bill, which, unlike the “pro-union” Wagner Act, was “drawn to give protection to all three groups [labor, business, and the public] of our citizenship.” As World War II progressed, such attacks on organized labor continued, with no clear evidence that prewar gains sacrificed for the duration of the war would be restored when the conflict was over.45 Given these dark clouds on the horizon, organized labor could not afford to become complacent, despite high weekly earnings and burgeoning union membership.

Indeed, for some unions in Milwaukee, organizing became a way of life as they fought recalcitrant employers who still considered collective bargaining to be a violation of their entrepreneurial rights. Because of employer intransigence, workers at J. Greenebaum Tanning Company and at foundries operated by William Grede never really progressed beyond the organizing stage. At Allis-Chalmers, talented and aggressive leadership founded UAW Local 248 (CIO), but relations between the company and the union can be characterized best as a perpetual struggle for control of the shop floor. Although war raged in Europe and Asia, workers never lost sight of the importance of their unions and were willing to fight for their rights even if such actions impeded the war effort.

On August 5, 1942, the employees of J. Greenebaum Tanning Company voted 568 to 278 for the CIO International Fur and Leather Workers Union. Contract negotiations began a month later but immediately stalled over the issues of wages, security, equal pay, and working conditions. Major James Holmes, the Conciliation Service mediator appointed to break the deadlock, found the company intransigent and, fearing that a work stoppage might be imminent, quickly urged that the dispute be certified to the WLB. Ten months later, the WLB granted maintenance of membership to the union, but denied the union’s request for a wage increase because raises already granted Greenebaum workers exceeded the 15 percent limit set by the WLB. Instead of a general wage increase, the WLB instructed the two parties to negotiate a pay plan that would eliminate intra-plant inequalities. For all practical purposes, the WLB action gave the workers a contract; but the company continued to stall on wage negotiations. At the end of 1943 the WLB again addressed the matter and, in time for Independence Day 1944, ordered that the old contract be carried over and that the company begin negotiating with the union. With this order in hand, the management of the tannery found a new way to avoid meeting with the union. The old contract required that they bargain with Local 260, but the old local had merged with another Fur and Leather workers local, becoming Local 47. Seizing upon this technicality, the Greenebaum Tannery argued that there was no certified agent with whom they could bargain legitimately. Not until December 1944—more than two years after the union won its election—did the Greenebaum company finally agree to carry over the old contract with its union security clauses intact and begin negotiating.

It had been a long battle, and the union had progressed only slightly beyond the stage of organizing the plant. It had little to show for its efforts other than what the WLB had granted. The company refused to enter into a productive labor-management relationship and insisted on operating its affairs as if there had been no war. At the Greenebaum tannery, the union and the workers paid more heed to the war effort and stayed on the job as the WLB slowly adjudicated their cases. It was the company’s intransigence that prevented the union from moving beyond simple self-preservation to greater labor-management cooperation on behalf of the war effort.46

Although the experience at Greenebaum may have been frustrating to the workers, it could not compare with the treatment received by workers at William Grede’s foundries in Milwaukee. Grede was an old-fashioned industrialist who refused to acknowledge that the Wagner Act gave workers the right to organize. Locals of the Steelworkers’ Organizing Committee in his plants found it almost impossible to get recognition from management representatives. Grede was so successful in his opposition to the union that the steelworkers never progressed much beyond the stage of running organizing campaigns.

In December 1942 William Grede purchased the Smith Steel Foundry, where United Steelworkers Local 1300 had a valid contract. Grede immediately fired all the employees, offering to rehire them with the understanding that they were now dealing with a new management that had no contract with the union—a procedure upheld by the WLB. According to W. O. Sonnemann, a CIO attorney, “The position Mr. Grede has taken . . . is that when he took over Smith Steel all he bought was the buildings and machines.” For the remainder of the war, the workers in this plant tried to negotiate a contract. Grede’s inimitable negotiating style permitted him to meet with union officials and to avoid any direct action to destroy the union, while at the same time avoiding any action that might legitimate the union. Plainly put, Grede tied union negotiators into semantic knots. When discussing establishment of a grievance procedure, for example, he asked union officials, “Well, what is a grievance?” Grede immediately accepted the union’s definition of a grievance as an “unsatisfied complaint,” and then turned the definition against the union. If a grievance was an “unsatisfied complaint,” he argued, there was no need for a steward to present an employee’s complaint because a complaint was not a grievance until it was rejected by the company. Of course, any procedure that sidestepped the union steward was completely unacceptable to the union, so around and around went the debates. As James Holmes commented to his superiors in the Conciliation Service, a union representative told him “after you have argued for several years on such trivial matters, it is impossible to think clearly.”

Frustrated by such tactics, workers at Smith Steel struck on July 25, 1944, to protest company delays in contract negotiations. On May 3 of that year the union had been certified as the bargaining agent, and contract discussions had been stalled ever since. Fed up with non-coercive methods, the workers struck. Despite pressure from the international union, the steelworkers refused to return to their jobs. After eight days, Local 1568 at the Milwaukee Steel Foundry (another Grede division) joined the strike, having become equally impatient with Grede for his refusal to abide by a WLB directive that gave the union maintenance of membership, voluntary check-off, and grievance procedures. The company’s president argued that the labor board had gone beyond its jurisdiction in ordering implementation of these standard contract features. The members of Local 1300 and Local 1568 returned to work on August 7 after the parties agreed to negotiate the issues.

Seven months later, nothing had changed for the Smith Steel Foundry workers. Grede continued his delaying tactics; virtually the entire contract remained unsettled. James Holmes seemed exasperated with the company’s behavior and again certified this case to the WLB. Despite the lack of progress, the union agreed to wait for a labor board decision, and the workers stayed on the job. As the war drew to a close, the steelworkers in Grede’s plants were only one step beyond organizing. They were still trying to develop a stable relationship with an employer who refused to accept the union’s right to exist.47